Padmasambhava

Padmasambhāva | |

|---|---|

Padmasambhava statue at Ghyoilisang peace park, Boudhanath | |

| Born | |

| Occupation | Vajra master |

| Known for | Credited with founding the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism |

Padmasambhava ("Born from a Lotus"),[note 1] also known as Guru Rinpoche (Precious Guru) and the Lotus from Oḍḍiyāna, was a tantric Buddhist Vajra master from India who may have taught Vajrayana in Tibet (circa 8th - 9th centuries).[1][2][3][4] According to some early Tibetan sources like the Testament of Ba, he came to Tibet in the 8th century and helped construct Samye Monastery, the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet.[3] However, little is known about the actual historical figure other than his ties to Vajrayana and Indian Buddhism.[5][6]

Padmasambhava later came to be viewed as a central figure in the transmission of Buddhism to Tibet.[7][5] Starting from around the 12th century, hagiographies concerning Padmasambhava were written. These works expanded the profile and activities of Padmasambhava, now seen as taming all the Tibetan spirits and gods, and concealing various secret texts (terma) for future tertöns.[8] Nyangral Nyima Özer (1124–1192) was the author of the Zangling-ma (Jeweled Rosary), the earliest biography of Padmasambhava.[9][10] He has been called "one of the main architects of the Padmasambhava mythos – who first linked Padmasambhava to the Great Perfection in a high-profile manner."[11][12]

In modern Tibetan Buddhism, Padmasambhava is considered to be a Buddha that was foretold by Buddha Shakyamuni.[2] According to traditional hagiographies, his students include the great female masters Yeshe Tsogyal and Mandarava.[5] The contemporary Nyingma school considers Padmasambhava to be a founding figure.[13][4] The Nyingma school also traditionally holds that its Dzogchen lineage has its origins in Garab Dorje through a direct transmission to Padmasambhava.[14]

In Tibetan Buddhism, the teachings of Padmasambava are said to include an oral lineage (kama), and a lineage of the hidden treasure texts (termas).[15] Tibetan Buddhism holds that Padmasambhava's termas are discovered by fortunate beings and tertöns (treasure finders) when conditions are ripe for their reception.[16] Padmasambhava is said to appear to tertöns in visionary encounters, and his form is visualized during guru yoga practice, particularly in the Nyingma school. Padmasambhava is widely venerated by Buddhists in Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, the Himalayan states of India, and in countries around the world.[17][18]

History[edit]

According to Lewis Doney, while his historical authenticity was questioned by earlier Tibetologists, it is now "cautiously accepted".[4]

Early sources[edit]

One of the earliest chronicle sources for Padmasambhava as a historical figure is the Testament of Ba (Dba' bzhed, c. 9th–12th centuries), which records the founding of Samye Monastery under the reign of King Trisong Detsen (r. 755–797/804).[19][4] Other early manuscripts from Dunhuang also mention a tantric master associated with kilaya rituals named Padmasambhava who tames demons, though they do not associate this figure with Trisong Detsen.[20][4]

According to the Testament of Ba, Trisong Detsen had invited the Buddhist abbot and philosopher Śāntarakṣita (725–788) to Tibet to propagate Buddhism and help found the first Buddhist monastery at Samye ('The Inconceivable'). However, certain events like the flooding of a Buddhist temple and lightning striking the royal palace had caused some at the Tibetan court to believe that the local gods were angry.[3]

Śāntarakṣita was sent back to Nepal, but was then asked to return after the anti-Buddhist sentiments had subsided. On his return, Śāntarakṣita brought Padmasambhava who was an Indian tantric adept from Oddiyana, in present-day Swat Valley, Pakistan.[21][22][23] Padmasambhava's task was to tame the local spirits and impress the Tibetans with his magical and ritual powers. The Tibetan sources then explain how Padmasambhava identified the local gods and spirits, called them out and threatened them with his powers. After they had been tamed, the construction of Samye went ahead.[3] Padmasambhava was also said to have taught various forms of tantric Buddhist yoga.[24]

When the royal court began to suspect that Padmasambhava wanted to seize power, he was asked to leave by the king.[24] The Testament of Ba also mentions other miracles by Padmasambhava, mostly associated with the taming of demons and spirits as well as longevity rituals and water magic.[4]

Evidence shows that Padmasambhava's tantric teachings were being taught in Tibet during the 10th century. Recent evidence suggests that Padmasambhava already figured in spiritual hagiography and ritual, and was already seen as the enlightened source of tantric scriptures up to 200 years before Nyangrel Nyima Özer (1136–1204),[25] the primary source of the traditional hagiography of Padmasambhava.

Lewis Doney notes that while numerous texts are associated with Padmasambhava, the most likely of these attributions are the Man ngag lta ba'i phreng ba (The Garland of Views), a commentary on the 13th chapter of the Guhyagarbha tantra and the Thabs zhags padma 'phreng (A Noble Noose of Methods, The Lotus Garland), an exposition of Mahayoga. The former work is mentioned in the work of Nubchen Sangye Yeshe (c. 9-10th centuries) and attributed to Padmasambhava.[4]

Development of the mythos[edit]

While in the eleventh and twelfth centuries there were several parallel narratives of important founding figures like Padmasambhava, Vimalamitra, Songtsän Gampo, and Vairotsana, by the end of the 12th century, the Padmasambhava narrative grew to dominate the others, becoming the most influential legend of the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet.[26][27][28]

The first full biography of Padmasambhava is a terma (treasure text) said to have been revealed by Nyangrel Nyima Özer, abbot of Mawochok Monastery. This biography, "The Copper Palace" (bka' thang zangs gling ma), was very influential on the Padmasambhava hagiographical tradition. The narrative was also incorporated into Nyima Özer's history of Buddhism, the "Flower Nectar: The Essence of Honey" (chos 'byung me tog snying po sbrang rtsi'i bcud).[29][4][12][11]

The tertön Guru Chöwang (1212–1270) was the next major contributor to the Padmasambhava tradition, and may have been the first full life-story biographer of Yeshe Tsogyal.[12]

The basic narrative of The Copper Palace continued to be expanded and edited by Tibetans. In the 14th century, the Padmasambhava hagiography was further expanded and re-envisioned through the efforts of the Orgyen Lingpa (1323 – c. 1360). It is in the works of Orgyen Lingpa, particularly his Padma bka' thang (Lotus Testament, 1352), that the "11 deeds" of Padmasambhava first appear in full.[4] The Lotus Testament is a very extensive biography of Padmasambhava, which begins with his ordination under Ananda and contains numerous references to Padmasambhava as a "second Buddha."[4]

Hagiography[edit]

According to Khenchen Palden Sherab, there are traditionally said to be nine thousand nine hundred and ninety-nine biographies of Padmasambhava.[2] They are categorized in three ways: Those relating to Padmasambhava's Dharmakaya buddhahood, those accounts of his Sambhogakaya nature, and those chronicles of his Nirmanakaya activities.[2]

Birth and early life[edit]

Hagiographies of Padmasambhava such as The Copper Palace, depict Padmasambhava being born as an eight-year-old child appearing in a lotus blossom floating in Lake Dhanakosha surrounded by a host of dakinis, in the kingdom of Oddiyana.[4][30]

However there are other birth stories as well, another common one states that he was born from the womb of Queen Jalendra, the wife of king Sakra of Oddiyana and received the name Dorje Duddul (Vajra Demon Subjugator) because of the auspicious marks on his body were identified as those of a demon tamer.[4]

As Nyingma scholar Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche explains:

In The Copper Palace, King Indrabhuti of Oddiyana is searching for a wish fulfilling jewel and finds Padmasambhava, who is said to be an incarnation of Buddha Amitabha. The king adopts him as his own son and Padmasambhava is enthroned as the Lotus King (Pema Gyalpo).[4][30] However, Padmasambhava kills one of his ministers with his khaṭvāṅga staff and is exiled from the kingdom, which allows him to live as a mahasiddha and practice tantra in charnel grounds throughout India.[4][30][31]

In Himachal Pradesh, India at Rewalsar Lake, known as Tso Pema in Tibetan, Padmasambhava secretly gave tantric teachings to princess Mandarava, the local king's daughter. The king found out and tried to burn both him and his daughter, but it is said that when the smoke cleared they were still alive and in meditation, centered in a lotus arising from a lake. Greatly astonished by this miracle, the king offered Padmasambhava both his kingdom and Mandarava.[32]

Padmasambhava is then said to have returned home with Mandarava and together they converted the kingdom to Vajrayana Buddhism.[4]

They are also said to have travelled together to the Maratika Cave in Nepal to practice long life rituals of Amitāyus.[33]

Activities in Tibet[edit]

Padmasambhava hagiographies also discuss the activities of Padmasambhāva in Tibet, beginning with the invitation by King Trisong Detsen to help in the founding of Samye. Padmasambhava is depicted as a great tantric adept who tames the spirits and demons of Tibet and turns them into guardians for the Buddha's Dharma (specifically, the deity Pe har is made the protector of Samye). He is also said to have spread Vajrayana Buddhism to the people of Tibet, and specifically introduced its practice of Tantra.[34][35][4]

The subjection of subduing deities and demons is a recurrent theme in Buddhist literature, as noted also in Vajrapani and Mahesvara and Steven Heine's "Opening a Mountain".[36]

Because of his role in the founding of Samye monastery, the first monastery in Tibet, Padmasambhava is regarded as the founder of the Nyingma school ("Ancients") of Tibetan Buddhism.[37][38][39] Padmasambhava's activities in the Tibet include the practice of tantric rituals to increase the life of the king as well as initiating king Trisong Detsen into tantric rites.[4]

The various biographies also discuss stories of Padmasambhava's main Tibetan consort, princess Yeshe Tsogyal ("Knowledge Lake Empress"), who became his student while living in the court of Trisong Deutsen.[40] She was among Padmasambhava's three special students (along with the King, and Namkhai Nyingpo) and is widely revered in Tibet as the "Mother of Buddhism".[12] Yeshe Tsogyal became a great master with many disciples and is widely considered to be a female Buddha.[41]

Padmasambhava hid numerous termas in Tibet for later discovery with her aid, while she compiled and elicited Padmasambhava's teachings through the posing of questions, and then reached Buddhahood in her lifetime. Many thangkas and paintings depict Padmasambhava with consorts at each side, Mandarava on his right and Yeshe Tsogyal on his left.[42]

Many of the Nyingma school's terma texts are said to have originated from the activities of Padmasambhava and his students. These hidden treasure texts are believed to be discovered and disseminated when conditions are ripe for their reception.[14] The Nyingma school traces its lineage of Dzogchen teachings to Garab Dorje through Padmasambhava's termas.[15]

In The Copper Palace, after the death of Trisong Detsen, Padmasambhava is said to have treveled to Lanka in order to convert its blood thirsty raksasa demons to the Dharma. His parting words of advice advocates for the worship of Avalokiteshvara.[4]

Bhutan[edit]

Bhutan has many important pilgrimage places associated with Padmasambhava. The most famous is Paro Taktsang or "Tiger's Nest" monastery which is built on a sheer cliff wall about 900m above the floor of Paro valley. It was built around the Taktsang Senge Samdup (stag tshang seng ge bsam grub) cave where Padmasambhava is said to have meditated.[43]

He is said to have flown there from Tibet on the back of Yeshe Tsogyal, whom he transformed into a flying tigress for the purpose of the trip.[citation needed] Later he travelled to Bumthang district to subdue a powerful deity offended by a local king. According to legend, Padmasambhava's body imprint can be found in the wall of a cave at nearby Kurje Lhakhang temple.[citation needed]

Eight manifestations[edit]

The eight manifestations are also seen as Padmasambhava's biography that spans 1500 years. As Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche states,

In accord, Rigpa Shedra also states the eight principal forms were assumed by Guru Rinpoche at different points in his life. Padmasambhava's eight manifestations, or forms (Tib. Guru Tsen Gye), represent different aspects of his being as needed, such as wrathful or peaceful for example.

The Eight Manifestations of Padmasambhava belong to the tradition of Terma, the Revealed Treasures (Tib.: ter ma),[2][44][45] and are described and enumerated as follows:

- Guru Pema Gyalpo (Wylie: gu ru pad ma rgyal-po, Skt: Guru Padmarāja) of Oddiyana, meaning "Lotus King", king of the Tripitaka (the Three Collections of Scripture), manifests as a child four years after the Mahaparinirvana of Buddha Shakyamuni, as predicted by the Buddha. He is shown with a redish pink complexion and semi-wrathful, seated on a lotus and wearing yellow-orange robes, a small damaru in his right hand and a mirror and hook in his left hand, with a top-knot wrapped in white and streaming with red silk.

- Guru Nyima Ozer (Wylie: gu ru nyi-ma 'od-zer, Skrt: Guru Suryabhasa or Sūryaraśmi[46]), meaning "Ray of Sun", the Sunray Yogi, semi-wrathful, manifests in India simultaneously with Guru Pema Gyalpo, often portrayed as a crazy wisdom wandering yogi, numerous simultaneous emanations, illuminates the darkness of the mind through the insight of Dzogchen. He is shown seated on a lotus with left leg bent and with a golden-red complexion, semi-wrathful with slightly bulging eyes, long hair with bone ornaments, moustache and beard, bare-chested with a tiger-skin skirt, right hand holds a khatvanga and left hand is in a mudra, interacting with the sun.

- Guru Loden Chokse (Wylie: gu ru blo ldan mchog sred; Skrt: Guru Mativat Vararuci,[46]) meaning roughly "Super Knowledge Holder", peaceful, manifests after Guru Pema Gyalpo departs Oddiyana for the great charnel grounds of India and for all knowledge, the Intelligent Youth, the one who gathers the knowledge of all worlds. He is shown seated on a lotus, white complexion, wearing a white scarf with ribbons wrapped around his head, and a blue-green lotus decorating his hair, holding a damaru in the right hand and a lotus bowl in the left hand.

- Guru Padmasambhava (Skt: Guru Padmasambhava), meaning "Lotus Essence", a symbol of spiritual perfection, peaceful, manifests and teaches Mandarava, transforming negative energies into compassionate and peaceful forms. He is shown with a rich white complexion, very peaceful, and wears a red monk's hat, and sits on a lotus with his right hand in a mudra and left hand holding a skull-cup.

- Guru Shakya Senge (Wylie: shAkya seng-ge, Skt: Guru Śākyasimha) of Bodh Gaya, meaning "Undefeatable Lion", peaceful, manifests as Ananda's student and brings King Ashoka to the Dharma, Lion of the Sakyas, embodies patience and detachment, learns all Buddhist canons and Tantric practices of the eight Vidyadharas. He is shown similar to Buddha Shakymuni but with golden skin in red monk's robes, a unishaka, a begging bowl in the left hand and a five-pointed vajra in the right hand.

- Guru Senge Dradrog (Wylie: gu ru seng-ge sgra-sgrogs, Skt: Guru Simhanāda,[46]) meaning "The Lion's Roar", wrathful, subdues and pacifies negative influences, manifests in India and at Nalanda University, the Lion of Debate, promulgator of the Dharma throughout the six realms of sentient beings. He is shown as dark blue and surrounded by flames above a lotus, with fangs and three glaring eyes, crown of skulls and long hair, standing on a demon, holding a flaming vajra in the right hand, left hand in a subjugation mudra.

- Guru Pema Jungne (Wylie: pad ma 'byung-gnas, Skt: Guru Padmakara), meaning "Born from a Lotus", manifests before his arrival in Tibet, the Vajrayana Buddha that teaches the Dharma to the people, embodies all manifestations and actions of pacifying, increasing, magnetizing and subjugating. As the most depicted manifestation, he is shown sitting on a lotus, dressed in three robes, under which he wears a blue shirt, pants and Tibetan shoes. He holds a vajra in his right hand, and a skull-bowl with a small vase in his left hand. A special trident called a khatvanga leans on the left shoulder representing Yeshe Tsogyal, and he wears a Nepalese cloth hat in the shape of a lotus flower. Thus he is represented as he must have appeared in Tibet.

- Guru Dorje Drolo (Wylie: gu ru rDo-rje gro-lod, Skt: Guru Vajra), meaning "Crazy Wisdom", very wrathful, manifests five years before Guru Pema Jungne departs Tibet, 13 emanations for 13 Tiger's Nests caves, the fierce manifestation of Vajrakilaya (wrathful Vajrasattva) known as "Diamond Guts", the comforter of all, imprinting the elements with Wisdom-Treasure, subduer for degenerate times. He is shown dark red, surrounded by flames, wearing robes and Tibetan shoes, conch earrings, a garland of heads, dancing on a tiger, symbolizing Tashi Kyeden, that is also dancing.

Padmasambhava's various Sanskrit names are preserved in mantras such as those found in the Yang gsang rig 'dzin youngs rdzogs kyi blama guru mtshan brgyad bye brag du sgrub pa ye shes bdud rtsi'i sbrang char zhe bya ba.[clarification needed][46][47]

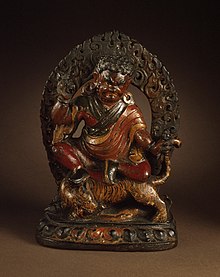

Iconography[edit]

Padmasambhava has one face and two hands.[48][49] He is wrathful and smiling.[48] He blazes magnificently with the splendour of the major and minor marks.[48] His two eyes are wide open in a piercing gaze.[48] He has the youthful appearance of an eight-year-old child.[49] His complexion is white with a tinge of red.[49] He is seated with his two feet in the royal posture.[48][49][50]

On his head he wears a five-petalled lotus hat,[48][50] which has three points symbolizing the three kayas, five colours symbolizing the five kayas, the sun and moon symbolizing skillful means and wisdom, a vajra top to symbolize unshakable samadhi, and a vulture's feather to represent the realization of the highest view.[49]

Padmasambhava wears a white vajra undergarment. On top of this, in layers, a red robe, a dark blue mantrayana tunic, a red monastic shawl decorated with a golden flower pattern, and a maroon cloak of silk brocade.[48] Also, he wears a silk cloak, Dharma robes and gown.[50] He is wearing the dark blue gown of a mantra practitioner, the red and yellow shawl of a monk, the maroon cloak of a king, and the red robe and secret white garments of a bodhisattva.[49]

In his right hand, he holds a five-pronged vajra at his heart.[48][49][50] His left hand rests in the gesture of equanimity,[48] In his left hand he holds a skull-cup brimming with nectar, containing the vase of longevity that is also filled with the nectar of deathless wisdom[48][49] and ornamented on top by a wish-fulfilling tree.[50]

Cradled in his left arm he holds the three-pointed khatvanga (trident) symbolizing the Princess consort Mandarava, one of his two main consorts.[48][50] who arouses the wisdom of bliss and emptiness, concealed as the three-pointed khatvanga.[49] Other sources say that the khatvanga represents the Lady Yeshe Tsogyal, his primary consort and main disciple.[51] Its three points represent the essence, nature and compassionate energy (ngowo, rangshyin and tukjé).[49][50] Below these three prongs are three severed heads, dry, fresh and rotten, symbolizing the dharmakaya, sambhogakaya and nirmanakaya.[49][50] Nine iron rings adorning the prongs represent the nine yanas.[49][50] Five-coloured strips of silk symbolize the five wisdoms[49] The khatvanga is also adorned with locks of hair from dead and living mamos and dakinis, as a sign that the Master subjugated them all when he practised austerities in the Eight Great Charnel Grounds.[49][50]

Around him within a lattice of five-coloured light, appear the eight vidyadharas of India, the twenty-five disciples of Tibet, the deities of the three roots, and an ocean of oath-bound protectors[50]

Attributes[edit]

Pureland paradise[edit]

His pureland paradise is Zangdok Palri (the Copper-Coloured Mountain).[52]

Samantabhadra and Samantabhadri[edit]

Padmasambhava said:

Another translation of Guru Rinpoche's statement is:

Practices associated with Padmasambhava[edit]

From the earliest sources to today, Padmasambhava has remained closely associated with the Kila (phurba) dagger and also with the deity Vajrakilaya (a meditation deity based on the kila).[4]

Vajra Guru mantra[edit]

The Vajra Guru mantra is:

Like most Sanskrit mantras in Tibet, the Tibetan pronunciation demonstrates dialectic variation and is generally Om Ah Hung Benza Guru Pema Siddhi Hung.

In the Tibetan Buddhist traditions, particularly in Nyingma, the Vajra Guru mantra is held to be a powerful mantra engendering communion with the Three Vajras of Padmasambhava's mindstream and by his grace, all enlightened beings.[53] The 14th century tertön Karma Lingpa wrote a famous commentary on the mantra.[54]

According to the great tertön Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, the basic meaning of the mantra is:

Seven Line Prayer[edit]

The Seven Line Prayer to Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) is a famous prayer that is recited by many Tibetans daily and is said to contain the most sacred and important teachings of Dzogchen. It is as follows:[56]

Sanskrit:

Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso composed a famous commentary to the Seven Line Prayer called White Lotus. It explains the meaning of the prayer in five levels of meaning intended to catalyze a process of realization. These hidden teachings are described as ripening and deepening, in time, with study and with contemplation.[57] There is also a shorter commentary by Tulku Thondup.[58]

Cham dances[edit]

The life of Padmasambhava is widely depicted in the Cham dances which are masked and costumed dances associated with religious festivals in the Tibetan Buddhist world.[59] In Bhutan, the dances are performed during the annual religious festivals or tshechu.

Terma cycles[edit]

There are numerous Terma cycles which are believed to contain teachings of Padmasambhava.[60] According to Tibetan tradition, the Bardo Thodol (commonly referred to as the Tibetan Book of the Dead) was among these hidden treasures, subsequently discovered by a Tibetan tertön, Karma Lingpa (1326–1386).

Tantric cycles related to Padmasambhava are not just practiced by the Nyingma, they even gave rise to a new offshoot of Bön which emerged in the 14th century called the New Bön. Prominent figures of the Sarma (new translation) schools such as the Karmapas and Sakya lineage heads have practiced these cycles and taught them. Some of the greatest s who revealed teachings related to Padmasambhava have been from the Kagyu or Sakya lineages. The hidden lake temple of the Dalai Lamas behind the Potala Palace, called Lukhang, is dedicated to Dzogchen teachings and has murals depicting the eight manifestations of Padmasambhava.[61]

Five main consorts[edit]

Many of the students gathered around Padmasambhāva became advanced Vajrayana tantric practitioners, and became enlightened. They also founded and propagated the Nyingma school. The most prominent of these include Padmasambhāva's five main female consorts, often referred to as wisdom dakinis, and his twenty five main students along with king Trisong Detsen.

Padmasambhāva had five main female tantric consorts, beginning in India before his time in Tibet and then in Tibet as well. When seen from an outer, or perhaps even historical or mythological perspective, these five women from across South Asia were known as the Five Consorts. That the women come from very different geographic regions is understood as a mandala, a support for Padmasambhāva in spreading the dharma throughout the region.

Yet, when understood from a more inner tantric perspective, these same women are understood not as ordinary women but as wisdom dakinis. From this point of view, they are known as the "Five Wisdom Dakinis" (Wylie: Ye-shes mKha-'gro lnga). Each of these consorts is believed to be an emanation of the tantric yidam, Vajravārāhī.[62] As one author writes of these relationships:

In summary, the five consorts/wisdom dakinis were:

- Yeshe Tsogyal of Tibet, who was the emanation of Vajravarahi's Speech (Tibetan: gsung; Sanskrit: vāk);

- Mandarava of Zahor, northeast India, who was the emanation of Vajravarahi's Body (Tibetan: sku; Sanskrit: kāya);

- Belwong Kalasiddhi of northwest India, who was the emanation of Vajravarahi's Quality (Tibetan: yon-tan; Sanskrit: gūna);

- Belmo Sakya Devi of Nepal, who was the emanation of Vajravarahi's Mind (Tibetan: thugs; Sanskrit: citta); and

- Tashi Kyeden (or Kyedren or Chidren), sometimes called Mangala, of Bhutan and Tiger's Nest caves, is an emanation of Vajravarahi's Activity (Tibetan: phrin-las; Sanskrit: karma).[64] Tashi Kyeden is often depicted with Guru Dorje Drolo.[2]

While there are very few sources on the lives of Kalasiddhi, Sakya Devi, and Tashi Kyedren, there are extant biographies of both Yeshe Tsogyal and Mandarava that have been translated into English and other western languages.

Twenty-five main students[edit]

Padmasambhava has twenty five main students (Tibetan: རྗེ་འབངས་ཉེར་ལྔ, Wylie: rje 'bangs nyer lnga) in Tibet during the Nyingma's school's Early Translation period. These students are also called the "Twenty-five King and subjects" and "The King and 25" of Chimphu.[65] [66] In Dudjom Rinpoche's list,[67] and in other sources, these include:

- Denma Tsémang (Tibetan: ལྡན་མ་རྩེ་མང, Wylie: ldan ma rtse mang) [68]

- Nanam Dorje Dudjom, Dorje Dudjom of Nanam (Tibetan: རྡོ་རྗེ་བདུད་འཇོམ, Wylie: rdo rje bdud 'joms) [69] (image on Wikimedia commons)

- Drokben Khyechung Lotsawa (Tibetan: ཁྱེའུ་ཆུང་ལོ་ཙཱ་བ, Wylie: khye'u chung lo tsā ba)

- Lasum Gyelwa Changchup, Gyalwa Changchub of Lasum (Tibetan: ལ་སུམ་རྒྱལ་བ་བྱང་ཆུབ, Wylie: la sum rgyal ba byang chub) [70] (image on Wikimedia commons)

- Gyalwa Choyang (Tibetan: རྒྱལ་བ་མཆོག་དབྱངས, Wylie: rgyal ba mchog dbyangs) [71]

- Dre Gyelwei Lodro, Gyalwe Lodro of Dré (Tibetan: རྒྱལ་བའི་བློ་གྲོས, Wylie: rgyal ba'i blo gros) [72]

- Nyak Jnanakumara, Jnanakumara of Nyak (Tibetan: གཉགས་ཛཉའ་ན་ཀུ་མ་ར, Wylie: gnyags dzny' na ku ma ra) [73]

- Kawa Paltsek (Tibetan: སྐ་བ་དཔལ་བརྩེགས, Wylie: ska ba dpal brtsegs) [74]

- Karchen Za, Khandro Yeshe Tsogyal the princess of Karchen (Tibetan: མཁར་ཆེན་བཟའ་མཚོ་རྒྱལ, Wylie: mkhar chen bza' mtsho rgyal)

- Langdro Konchok Jungue, Konchog Jungné of Langdro (Tibetan: ལང་གྲོ་དཀོན་མཆོག་འབྱུང་གནས, Wylie: lang gro dkon mchog 'byung gnas) [75]

- Sogdian Lhapel, Lhapal the Sokpo (Tibetan: སོག་པོ་ལྷ་དཔལ, Wylie: sog po lha dpal) [76]

- Namkhai Nyingpo (Tibetan: ནམ་མཁའི་སྙིང་པོ, Wylie: nam mkha'i snying po)

- Nanam Zhang Yeshe De (Tibetan: ཞང་ཡེ་ཤེས་སྡེ, Wylie: zhang ye shes sde)

- Lhalung Pelgi Dorje, Lhalung Pelgyi Dorje (Tibetan: ལྷ་ལུང་དཔལ་གྱི་རྡོ་རྗེ, Wylie: lha lung dpal gyi rdo rje) [77]

- Shuphu Pelgi Senge, Palgyi Senge (Tibetan: དཔལ་གྱི་སེང་གེ, Wylie: dpal gyi seng ge) [78]

- Karchen Palgyi Wangchuk (Tibetan: དཔལ་གྱི་དབང་ཕྱུག, Wylie: dpal gyi dbang phyug) [79]

- Odren Pelgi Wangchuk, Palgyi Wangchuk of Odren (Tibetan: འོ་དྲན་དཔལ་གྱི་དབང་ཕྱུག, Wylie: 'o dran dpal gyi dbang phyug) [80]

- Palgyi Yeshe (Tibetan: དཔལ་གྱི་ཡེ་ཤེས, Wylie: dpal gyi ye shes)

- Ma Rinchen-chok, Rinchen Chok of Ma (Tibetan: རྨ་རིན་ཆེན་མཆོག, Wylie: rma rin chen mchog) [81]

- Nubchen Sangye Yeshe (Tibetan: སངས་རྒྱས་ཡེ་ཤེས, Wylie: sangs rgyas ye shes), reincarnated as Tsasum Lingpa[82]

- Shubu Palgyi Senge (Tibetan: ཤུད་བུ་དཔལ་གྱི་སེང་གེ, Wylie: shud bu dpal gyi seng ge)

- Vairocana, Vairotsana, the great translator (Tibetan: བཻ་རོ་ཙ་ན, Wylie: bai ro tsa na)

- Yeshe Yang (Tibetan: ཡེ་ཤེས་དབྱངས, Wylie: ye shes dbyangs) [83]

- Gyelmo Yudra Nyingpo, Yudra Nyingpo of Gyalmo (Tibetan: ག་ཡུ་སྒྲ་སྙིང་པོ, Wylie: g.yu sgra snying po)

Also, but not listed in the 25:

- Vimalamitra (Tibetan: དྲུ་མེད་བཤེས་གཉེན, Wylie: dru med bshes gnyen)

- Tingdzin Zangpo (Tibetan: ཏིང་འཛིན་བཟང་པོ, Wylie: ting 'dzin bzang po) [84] (image on Wikimedia commons)

In addition to Yeshe Tsogyal, 15 other women practitioners became accomplished Nyingma masters during this Early Translation period of the Nyingma school:[67][14]

- Tsenamza Sangyetso

- Shekar Dorjetso

- Tsombuza Pematso

- Melongza Rinchensho

- Ruza Tondrupma

- Shubuza Sherampa

- Yamdrokza Choki Dronma

- Oceza Kargyelma

- Dzemza Lhamo

- Barza Lhayang

- Chokroza Changchupman

- Dronma Pamti Chenmo

- Rongmenza Tsultrim-dron

- Khuza Peltsunma

- Trumza Shelmen

Gallery[edit]

Biographies in English[edit]

- Adzom Drukpa. Biography of Orgyen Guru Pema Jungne. Translated by Padma Samye Ling. Dharma Samudra.

- Chokgyur Lingpa, Orgyen (1973). The Legend of the Great Stupa and the Life Story of the Lotus Born Guru. Translated by Keith Dowman. Dharma Publishing.

- Chokgyur Lingpa (2016). "The Wish-Fulfilling Tree". The Great. Translated by Phakchok Rinpoche. Lhasey Lotsawa Publications.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon (1999). "A Short Biography of Padmasambhava". Dakini Teachings. Translated by Erik Pema Kunsang. Rangjung Yeshe Publishing.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon (2005). The Vajra Garland and the Lotus Garden: Treasure Biographies of Padmakara and Vairochana. Translated by Yeshe Gyamtso. KTD Publications.

- Kongtrul, Jamgön (2019). Following in Your Footsteps: The Lotus-Born Guru in Nepal. Translated by Neten Chokling Rinpoche & Lhasey Lotsawa Translations. Rangjung Yeshe Publishing.

- Lotsawa, Lhasey (2021). Following in Your Footsteps: The Lotus-Born Guru in India. Rangjung Yeshe.

- Orgyen Padma (2004). The Condensed Chronicle. Translated by Tony Duff. Padma Karpo Translation Committee.

- Sogyal Rinpoche (1990). Dzogchen and Padmasambhava. Rigpa International.

- Yeshe Tsogyal (1978). The Life and Liberation of Padmasambhava. Padma bKa'i Thang. (Parts I & II). Translated by Gustave-Charles Toussaint; Kenneth Douglas; Gwendolyn Bays. Dharma Publishing. ISBN 0-913546-18-6 and ISBN 0-913546-20-8.

- Yeshe Tsogyal (1993). Binder Schmidt, M.; Hein Schmidt, E. (eds.). The Lotus-Born: The Life Story of Padmasambhava. Translated by Erik Pema Kunsang. Boston: Shambhala Publications. Reprint: Boudhanath: Rangjung Yeshe Publications, 2004. ISBN 962-7341-55-X.

- Yeshe Tsogyal (2009). Padmasambhava Comes to Tibet. Translated by Tarthang Tulku. Dharma Publishing.

- Taranatha (2005). The Life of Padmasambhava. Translated by Cristiana de Falco. Shang Shung Publications.

- Zangpo, Ngawang (2002). Guru Rinpoché: His Life and Times. Snow Lion Publications.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Kværne, Per (2013). Tuttle, Gray; Schaeffer, Kurtis R. (eds.). The Tibetan history reader. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-231-14469-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, The Eight Manifestations of Guru Padmasambhava, (May 1992), https://turtlehill.org/cleanup/khen/eman.html

- ^ a b c d Schaik, Sam van. Tibet: A History. Yale University Press 2011, pp. 34-35.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Doney, Lewis. "Padmasambhava in Tibetan Buddhism" in Silk, Jonathan A. et al. Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism, pp. 1197-1212. BRILL, Leiden, Boston.

- ^ a b c Schaik, Sam van. Tibet: A History. Yale University Press 2011, page 34-5, 96-8.

- ^ Kværne, Per (2013). Tuttle, Gray; Schaeffer, Kurtis R. (eds.). The Tibetan history reader. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-231-14469-8.

- ^ Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Jr., Donald S. (2013). The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 608. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ Schaik, Sam van. Tibet: A History. Yale University Press 2011, p. 96.

- ^ Doney, Lewis. The Zangs gling ma. The First Padmasambhava Biography. Two Exemplars of the Earliest Attested Recension. 2014. MONUMENTA TIBETICA HISTORICA Abt. II: Band 3.

- ^ Dalton, Jacob. The Early Development of the Padmasambhava Legend in Tibet: A Study of IOL Tib J 644 and Pelliot tibétain 307. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 124, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 2004), pp. 759- 772

- ^ a b Germano, David (2005), "The Funerary Transformation of the Great Perfection (Rdzogs chen)", Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies (1): 1–54

- ^ a b c d Gyatso, Janet (August 2006). "A Partial Genealogy of the Lifestory of Ye shes mtsho rgyal". The Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies (2).

- ^ Harvey, Peter (2008). An Introduction to Buddhism Teachings, History and Practices (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-521-67674-8. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal. Lion's Gaze: A Commentary on Tsig Sum Nedek. Sky Dancer Press, 1998.

- ^ a b Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, Beauty of Awakened Mind: The Dzogchen Lineage of Shigpo Dudtsi. Dharma Samudra, 2013. https://www.padmasambhava.org/chiso/books-by-khenpo-rinpoches/beauty-of-awakened-mind-dzogchen-lineage-of-shigpo-dudtsi/

- ^ Fremantle, Francesca (2001). Luminous Emptiness: Understanding the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 1-57062-450-X p.19

- ^ "Padmasambhava". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Jr., Donald S. (2013). The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 608. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ van Schaik, Sam; Iwao, Kazushi (2009). "Fragments of the Testament of Ba from Dunhuang". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 128 (3): 477–487. ISSN 0003-0279

- ^ Schaik, Sam van. Tibet: A History. Yale University Press 2011, pp. 34-5, 96-8, 273.

- ^ Meulenbeld, Ben (2001). Buddhist Symbolism in Tibetan Thangkas: The Story of Siddhartha and Other Buddhas Interpreted in Modern Nepalese Painting. Binkey Kok. p. 93. ISBN 978-90-74597-44-9.

- ^ Kazi, Jigme N. (2020-10-20). Sons of Sikkim: The Rise and Fall of the Namgyal Dynasty of Sikkim. Notion Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-64805-981-0.

- ^ Schaik, Sam Van (2011-06-28). Tibet: A History. Yale University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-300-17217-1.

- ^ a b Schaik, Sam van. Tibet: A History. Yale University Press 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Cantwell, Cathy;Mayer, Rob; REPRESENTATIONS OF PADMASAMBHAVA IN EARLY POST-IMPERIAL TIBET(pg.22). https://ocbs.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Cantwell-Mayer-Early-Representations-of-Padmasambhava-copy.pdf

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Tibetan Renaissance. pg 229. Columbia University Press, 2005.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Tibetan Renaissance. pg 278. Columbia University Press, 2005.

- ^ Schaik, Sam van. Tibet: A History. Yale University Press 2011, page 96.

- ^ Daniel Hirshberg, Nyangrel Nyima Ozer, Treasury of Lives, April 2013, https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Nyangrel-Nyima-Ozer/TBRC_P364

- ^ a b c Trungpa (2001) pp. 26-27. For debate on its geographical location, see also the article on Oddiyana.

- ^ Morgan (2010) 208.

- ^ Lama Chonam and Sangye Khandro, translators. The Lives and Liberation of Princess Mandarava: The Indian Consort of Padmasambhava. (1998). Wisdom Publications.

- ^ Maratika, http://www.treasuryoflives.org/institution/Maratika

- ^ Snelling 1987.

- ^ Harvey 1995.

- ^ Heine 2002.

- ^ Norbu 1987, p. 162.

- ^ Snelling 1987, p. 198.

- ^ Snelling 1987, p. 196, 198.

- ^ 'Guru Rinpoche' and 'Yeshe Tsogyal' in: Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2013). The Illustrated Tibetan Book of the Dead. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. B00BCRLONM

- ^ Changchub, Gyalwa; Namkhai Nyingpo (2002). Padmakara Translation Group (ed.). Lady of the Lotus-Born: The Life and Enlightenment of Yeshe Tsogyal. Shambhala Publications, Inc. p. xxxvii. ISBN 1-57062-544-1.

- ^ "Padmasambhava - The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters". Archived from the original on 2016-05-06. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ^ Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, The Eight Manifestations of Guru Rinpoche, (May 1992), https://turtlehill.org

- ^ Eight Manifestations of Guru Rinpoche, Rigpawiki, http://www.rigpawiki.org/index.php?title=Eight_Manifestations_of_Guru_Rinpoche

- ^ For the eight manifestations as terma, see: Eight Manifestations: Dorje Drolo, http://www.himalayanart.org/image.cfm/261.html

- ^ a b c d Boord 1993, p. 115.

- ^ See also image + description

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, Illuminating the Excellent Path to Omniscience

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Chökyi Drakpa, A Torch for the Path to Omniscience: A Word by Word Commentary on the Text of the Longchen Nyingtik Preliminary Practices.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Patrul Rinpoche, Brief Guide to the Ngöndro Visualization

- ^ John Huntington and Dina Bangdel. The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, Ohio, and Serindia Publications, Chicago. 2004. p. 358.

- ^ Schmidt and Binder 1993, pp. 252-53.

- ^ Sogyal Rinpoche (1992). The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, pp. 386-389 Harper, San Francisco. ISBN 0-7126-5437-2.

- ^ Benefits and Advantages of the Vajra Guru Mantra

- ^ Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo. Illuminating the Excellent Path — Notes on the Longchen Nyingtik Ngöndro. Lotsawa House.

- ^ "Seven Line Prayer". Lotsawa House. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ White Lotus: An Explanation of the Seven-line Prayer to Guru Padmasambhava by Mipham Rinpoche, Ju and translated by the Padmakara Translation Group Archived 2009-01-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Commentary on the Seven Line Prayer to Guru Rinpoche". Archived from the original on 2008-01-07. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ Dancing on the demon's back: the dramnyen dance and song of Bhutan[permanent dead link], by Elaine Dobson, John Blacking Symposium: Music, Culture and Society, Callaway Centre, University of Western Australia, July 2003

- ^ Laird (2006) 90.

- ^ Ian A. Baker: The Lukhang: A hidden temple in Tibet.

- ^ Dowman, Keith. (1984). Sky Dancer: The Secret Life and Songs of the Lady Yeshe Tsogyel. p. 265.

- ^ Gyalwa Changchub and Namkhai Nyingpo, Lady of the Lotus-Born: The Life and Enlightenment of Yeshe Tsogyal, Shambhala (1999, pp. 3-4)

- ^ Tibetan Wylie transliteration and Sanskrit transliteration are found in Dowman, Keith. (1984). Sky Dancer: The Secret Life and Songs of the Lady Yeshe Tsogyel. p. 193.

- ^ Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, Illuminating the Path, pg 179. Padmasambhava Buddhist Center, 2008.

- ^ RigpaShedra

- ^ a b Dudjom Rinpoche, The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism: Its Fundamentals and History, pg 534-537. Translated by Gyurme Dorje and Matthew Kapstein. Boston: Wisdom Publications. 1991, 2002.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Denma Tsemang". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Nanam Dorje Dudjom". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Dorje, Gyurme (August 2008). "Lasum Gyelwa Jangchub". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Gyelwa Choyang". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Gyelwai Lodro". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Garry, Ron (August 2007). "Nyak Jñānakumara". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Kawa Peltsek". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Langdro Konchok Jungne". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Sokpo Pelgyi Yeshe". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Lhalung Pelgyi Dorje". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Lang Pelgyi Sengge". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Kharchen Pelgyi Wangchuk". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Odren Pelgyi Wangchuk". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Ma Rinchen Chok". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (December 2009). "Nubchen Sanggye Yeshe". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Arthur (August 2007). "Yeshe Yang". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Leschly, Jakob (August 2007). "Nyang Tingdzin Zangpo". The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

Sources[edit]

- Berzin, Alexander (November 10–11, 2000). "History of Dzogchen". Study Buddhism. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- Bischoff, F.A. (1978). Ligeti, Louis (ed.). "Padmasambhava est-il un personnage historique?". Csoma de Körös Memorial Symposium. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó: 27–33. ISBN 963-05-1568-7.

- Boord, Martin (1993). Cult of the Deity Vajrakila. Institute of Buddhist Studies. ISBN 0-9515424-3-5.

- Dudjom Rinpoche The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism: Its Fundamentals and History. Translated by Gyurme Dorje and Matthew Kapstein. Boston: Wisdom Publications. 1991, 2002. ISBN 0-86171-199-8.

- Guenther, Herbert V. (1996), The Teachings of Padmasambhava, Leiden: E.J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-10542-5

- Harvey, Peter (1995), An introduction to Buddhism. Teachings, history and practices, Cambridge University Press

- Heine, Steven (2002), Opening a Mountain. Koans of the Zen Masters, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Jackson, D. (1979) 'The Life and Liberation of Padmasambhava (Padma bKaí thang)' in: The Journal of Asian Studies 39: 123-25.

- Jestis, Phyllis G. (2004) Holy People of the World Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-355-6.

- Kinnard, Jacob N. (2010) The Emergence of Buddhism Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 0-8006-9748-0.

- Laird, Thomas. (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama. Grove Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1.

- Morgan, D. (2010) Essential Buddhism: A Comprehensive Guide to Belief and Practice Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-313-38452-5.

- Norbu, Thubten Jigme; Turnbull, Colin (1987), Tibet: Its History, Religion and People, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-021382-1

- Snelling, John (1987), The Buddhist handbook. A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice, London: Century Paperbacks

- Sun, Shuyun (2008), A Year in Tibet: A Voyage of Discovery, London: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-00-728879-3

- Thondup, Tulku. Hidden Teachings of Tibet: An Explanation of the Terma Tradition of the Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism. London: Wisdom Publications, 1986.

- Trungpa, Chögyam (2001). Crazy Wisdom. Boston: Shambhala Publications. ISBN 0-87773-910-2.

- Wallace, B. Alan (1999), "The Buddhist Tradition of Samatha: Methods for Refining and Examining Consciousness", Journal of Consciousness Studies 6 (2-3): 175-187 .

Further reading[edit]

- Padmasambhava. Advice from the Lotus-Born: A Collection of Padmasambhava's Advice to the Dakini Yeshe Tsogyal and Other Close Disciples. With Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. Rangjung Yeshe Publications, 2013.

External links[edit]

Quotations related to Padmasambhava at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Padmasambhava at Wikiquote Media related to Padmasambhava (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Padmasambhava (category) at Wikimedia Commons

베율

베율 ‘베율’. [SBS SBS ‘인생횡단’ 캡처]

‘베율’. [SBS SBS ‘인생횡단’ 캡처]