이소 (굴원)

《이소》(離騷)는 중국 전국 시대 초나라의 시인인 굴원이 지은 장편 서정시이다. 수많은 비유와 의태어의 조화를 통해 세상에 알려지지 않은 인물의 슬픔, 분노, 한탄과 신화적인 환상 세계로의 여행을 노래하고 있다.

줄거리[편집]

《이소》는 이름이 정칙(正則), 자가 영균(靈均)인 인물의 1인칭 시점에서 묘사하고 있다. 초반부에서 영균은 자신이 전욱의 후손임을 자처했고 인년 인월 인일(寅年 寅月 寅日)에 태어나서 뛰어난 재능을 자랑했다고 한다. 영균은 옛 선왕의 이상을 실현하는 주군(主君)을 위해서 분주하지만 오히려 간신들의 모함으로 인해 군주, 신하들과의 사이가 멀어지게 된다.

이권만을 쫓다가 세상을 알지 못한 영균은 타협을 거부하고 먼 곳으로 떠나게 된다. 여수(女嬃, 전통적으로는 굴원의 여동생이라고 함)는 그것을 말렸지만 영균은 원수(沅水, 원강), 상수(湘水, 상강)를 건너 남쪽에 위치한 창오산(蒼梧山)에 살고 있던 제순을 만나게 된다. 성철(聖哲)만이 천하를 다스린다는 제순의 이야기를 듣고 눈물을 흘린 영균은 자신의 주장에 확신을 갖고 하늘을 날아 곤륜(崑崙)의 현포에 도달하여 그곳에서 망서(望舒, 달의 마부), 비렴(飛廉, 바람의 신), 난황(鸞皇), 뇌사(雷師)를 비롯한 전설적인 신들을 거느리고 천계를 여행하게 된다. 이소는 천제(天帝)를 만나려고 했지만 천문(天門)을 지키고 있던 문지기에 의해 거부당하고 만다. 영균은 복비(宓妃), 유융(有娀)의 딸(제곡의 아내), 유우(有虞)의 둘째 딸(소강의 아내)에게 구혼했지만 모두 실패하고 만다.

영균은 영분(靈氛)의 점괘와 무함(巫咸)으로부터 보다 멀리 떨어진 곳으로 가라는 조언을 받았고 세계의 끝까지 여행하게 된다. 영균은 8마리의 용이 이끄는 수레를 이끌고 하늘로 비상하면서 여자를 찾으려고 했다. 하지만 고향만 보인다는 사실을 알게 된 영균은 슬픔에 빠지면서 수레를 멈추게 된다.

특징[편집]

중국 전한 시대의 역사가인 사마천이 지은 역사서 《사기》(史記)의 《굴원전》(屈原傳)에 따르면 굴원이 초 회왕과의 갈등, 간신들의 모함으로 인해 초나라 궁정에서 쫓겨나서 유배 생활을 하던 도중에 세상에 대한 이상과 실망감을 담은 시 《이소》를 지었다고 한다. 《사기》에 따르면 '리'(離)는 만남(遭)을, '소'(騷)는 근심(憂)을 뜻하기 때문에 '이소'(離騷)는 "근심을 만난다"(離(리), 猶遭也(유조야). 騷(소), 憂也(우야).)는 뜻을 담고 있다고 설명했다. 전한 시대에 출간된 중국 고전 시가 작품집인 《초사》(楚辭)에도 《이소》가 게재되어 있다.

《이소》는 총 374구(句), 2,477자(字)로 구성되어 있다. 각 구의 길이는 반드시 같은 편이 아니지만 홀수 구는 "□□□△□□혜"(□□□△□□兮), 짝수 구는 "□□□△□□" 형식을 띠고 있다. 홀수 구의 △ 부분에는 '우'(于), '이'(以), '여'(與), '이'(而), '기'(其)를 비롯

==

Li Sao

Two pages from "Li Sao" from a 1645 illustrated copy of the Songs of Chu, showing the poem "The Lament", with its name being enhanced by the addition of the character 經 (jing), which is usually only so used in the case of referring to one of the Chinese classics. | |

| Author | (trad.) Qu Yuan |

|---|---|

| Published | c. 3rd century BCE |

| Li Sao | |||

|---|---|---|---|

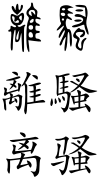

"Li Sao" in seal script (top), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 離騷 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 离骚 | ||

| Literal meaning | "Encountering Sorrow" | ||

| |||

Li Sao (Chinese: 離騷; pinyin: Lí Sāo; translation: "Encountering Sorrow") is a Chinese poem from the anthology Chuci, dating from the Warring States period of ancient China, generally attributed to Qu Yuan.

Background[edit]

The poem "Li Sao" is in the Chuci collection and was written by Qu Yuan[a] of the Kingdom of Chu, who died about 278 BCE.

Qu Yuan manifests himself in a poetic character, in the tradition of Classical Chinese poetry, contrasting with the anonymous poetic voices encountered in the Shijing and the other early poems which exist as preserved in the form of incidental incorporations into various documents of ancient miscellany. The rest of the Chuci anthology is centered on the "Li Sao", the purported biography of its author Qu Yuan.

In "Li Sao", the poet despairs that he has been plotted against by evil factions at court with his resulting rejection by his lord and then recounts a series of shamanistic spirit journeys to various mythological realms, engaging or attempting to engage with a variety of divine or spiritual beings, with the theme of the righteous minister unfairly rejected sometimes becoming exaggerated in the long history of later literary criticism and allegorical interpretation. It dates from the time of King Huai of Chu, in the late third century BCE.

Meaning of title[edit]

The meaning of the title "Li Sao" is not straightforward. In the biography of Qu Yuan, li sao is explained as being as equivalent to li you 'leaving with sorrow' (Sima Qian, Shiji or the Records of the Grand Historian). Inference must be made that 'meeting with sorrow' must have been meant.[1]

However, it is explicitly glossed as "encountering sorrow" in Ban Gu's commentary "Li Sao zan xu" (simplified Chinese: 离骚赞序; traditional Chinese: 離騷贊序 "Laudatory Preface to the Li Sao").[2][3]

Description[edit]

The Li Sao begins with the poet's introduction of himself, his ancestry, and his former shamanic glory.

Of the god-king Gao-yang I am the far offspring, | 帝高陽之苗裔兮, |

| —Li Sao, stanzas 1 to 3 (Owen, trans.)[4] |

He references his current situation, and then recounts the his fantastical physical and spiritual trip across the landscapes of ancient China, real and mythological. "Li Sao" is a seminal work in the large Chinese tradition of landscape and travel literature.[5] "The Lament" is also a political allegory in which the poet laments that his own righteousness, purity, and honor are unappreciated and go unused in a corrupt world. The poet alludes to being slandered by enemies and being rejected by the king he served (King Huai of Chu).

Those men of faction had ill-gotten pleasures, | 惟黨人之偷樂兮, |

| —Li Sao, stanzas 9 to 11 (Owen, trans.)[6] |

As a representative work of Chu poetry it makes use of a wide range of metaphors derived from the culture of Chu, which was strongly associated with a Chinese form of shamanism, and the poet spends much of "Li Sao" on a spirit journey visiting with spirits and deities. The poem's main themes include Qu Yuan's falling victim to intrigues in the court of Chu, and subsequent exile; his desire to remain pure and untainted by the corruption that was rife in the court; and also his lamentation at the gradual decline of the once-powerful state of Chu.

The poet decides to leave and join Peng Xian (Chinese: 彭咸), a figure that many believe to be the God of Sun. Wang Yi, the Han dynasty commentator to the Chuci, believed Peng Xian to have been a Shang dynasty official who, legend says, drowned himself after his wise advice was rejected by the king (but this legend may have been of later make, influenced by the circumstances of Qu Yuan drowning himself).[7] Peng Xian may also have been an ancient shaman who later came to symbolize hermit seclusion.[8]

It is now done forever! | 已矣哉, |

| —Li Sao, ending song (Owen, trans.)[9] |

The poem has a total of 373 lines[10] and about 2400 characters, which makes it one of the longest poems dating from Ancient China. It is in the fu style.[10] The precise date of composition is unknown, it would seem to have written by Qu Yuan after his exile by King Huai; however, it seems to have been before Huai's captivity in the state of Qin began, in 299 BCE.

Reissue[edit]

The poem was reissued in the 19th century by Pan Zuyin (1830–90), a linguist who was a member of the Qing Dynasty staff. It was reissued as four volumes with two prefaces, with one by Xiao Yuncong.[11]

Translations into Western languages[edit]

- English

- E.H. Parker (1878–1879). "The Sadness of Separation or Li Sao". China Review 7: 309–14.

- James Legge (1895). The Chinese Classics (Oxford: Clarendon Press): 839–64.

- Lim Boon Keng (1935). The Li Sao: An Elegy on Encountering Sorrows by Ch'ü Yüan (Shanghai: Commercial Press): 62–98.

- David Hawkes (1959). Ch'u Tz'u: Songs of the South, an Ancient Chinese Anthology (Oxford: Clarendon Press): 21–34.

- Stephen Owen (1996). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911 (New York: W.W. Norton): 162–75.

- Red Pine (2021). A Shaman's Lament (Empty Bowl).

- French

- Marie-Jean-Léon, Marquis d'Hervey de Saint Denys (1870). Le Li sao, poéme du IIIe siècle avant notre ére, traduit du chinois (Paris: Maisonneuve).

- J.-F. Rollin (1990). Li Sao, précédé de Jiu Ge et suivie de Tian Wen de Qu Yuan (Paris: Orphée/La Différence), 58–91.

- Italian

- G.M. Allegra (1938). Incontro al dolore di Kiu Yuan (Shanghai: ABC Press).

See also[edit]

- Chu Ci

- Kunlun Mountain (mythology)

- List of Chu Ci contents

- Liu An

- Liu Xiang (scholar)

- Qu Yuan

- Wang Yi (librarian)

- Wu (shaman)

- Xiao Yuncong

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Qu Yuan 屈原, alias Qu Ping 屈平.

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ Zikpi (2014), p. 110, 114

- ^ Zikpi (2014), p. 137, 279, citing Cui & Li (2003), pp. 5–6: "'Li' is like 'to meet with'; 'Sao'is 'sorrow'; to express that he met with sorrow and composed the lyrics 離,猶遭也。騷,憂也。明己遭憂作辭也".

- ^ Su, Xuelin 苏雪林, ed. (2007). Chusao xingu 楚骚新诂. Wuhan University. p. 4.

离,犹遭也。骚,忧也

- ^ Owen (1996), p. 162.

- ^ Stephen Owen, An Anthology of Chinese Literature – Beginnings to 1911 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 176.

- ^ Owen (1996), pp. 163–64.

- ^ Knechtges (2010), p. 145.

- ^ David Hawkes, Ch'u Tz'u: Songs of the South, an Ancient Chinese Anthology (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1959), 21.

- ^ Owen (1996), p. 175.

- ^ a b Davis (1970), p. xlvii.

- ^ "Illustrated Poem of Li Sao". World Digital Library. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- Works cited

- Cui, Fuzhang 崔富章; Li, Daming 李大明, eds. (2003). Chuci jijiao jishi 楚辭集校集釋 [Collected Collations and Commentaries on the Chuci]. Chuci xue wenku 楚辞学文库 1. Wuhan: Hubei jiaoyu chubanshe.

- Davis, A. R., ed. (1970). The Penguin Book of Chinese Verse. Baltimore: Penguin Books.

- Hawkes, David (1959). Ch'u Tz'u: Songs of the South, an Ancient Chinese Anthology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hawkes, David, trans. (2011 [1985]). The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044375-2

- Hawkes, David (1993). "Ch'u tz'u 楚辭". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 48–55. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Hinton, David (2008). Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-10536-7 / ISBN 978-0-374-10536-5

- Knechtges, David R. (2010). "Chu ci 楚辭 (Songs of Chu)". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part One. Leiden: Brill. pp. 144–147. ISBN 978-90-04-19127-3.

- Owen, Stephen (1996). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-97106-6.

- Yip, Wai-lim (1997). Chinese Poetry: An Anthology of Major Modes and Genres . (Durham and London: Duke University Press). ISBN 0-8223-1946-2

- Zikpi, Monica Eileen Mclellan (2014). Translating the Afterlives of Qu Yuan (PDF) (Ph. D.). New York: University of Oregon.

External links[edit]

- Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang, verse: full text, an English translation

Poems by Qu Yuan (340 - 278 B.C.)

poems translated by Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang

Li Sao (The Lament)

LI SAO (The Lament) is not only one of the most remarkable works of Qu Yuan, it ranks as one of the greatest poems in Chinese or world poetry. It was probably written during the period when the poet had been exiled by his king, and was living south of the Yangtse River.

The name LI SAO has been interpreted by some as meaning "encountering sorrow," by others as "sorrow after departure." Some recent scholars have construed it as "sorrow in estrangement," while yet others think it was the name of a certain type of music.

This long lyrical poem describes the search and disillusionment of a soul in agony, riding on dragons and serpents from heaven to earth. By means of rich imagery and skilful similes, it expresses love of one's country and the sadness of separation. It touches upon various historical themes intermingled with legends and myths, and depicts, directly or indirectly, the social conditions of that time and the complex destinies of the city states of ancient China. The conflict between the individual and the ruling group is repeatedly described, while at the same time the poet affirms his determination to fight for justice. This passionate desire to save his country, and this love for the people, account for the poem's splendour and immortality.

======

A prince am I of ancestry renowned,

Illustrious name my royal sire hath found.

When Sirius did in spring its light display,

A child was born, and Tiger marked the day.

When first upon my face my lord's eye glanced,

For me auspicious names he straight advanced,

Denoting that in me Heaven's marks divine

Should with the virtues of the earth combine.

With lavished innate qualities indued,

By art and skill my talents I renewed;

Angelic herbs and sweet selineas too,

And orchids late that by the water grew,

I wove for ornament; till creeping Time,

Like water flowing, stole away my prime.

Magnolias of the glade I plucked at dawn,

At eve beside the stream took winter-thorn.

Without delay the sun and moon sped fast,

In swift succession spring and autumn passed;

The fallen flowers lay scattered on the ground,

The dusk might fall before my dream was found.

Had I not loved my prime and spurned the vile,

Why should I not have changed my former style?

My chariot drawn by steeds of race divine

I urged; to guide the king my sole design.

Three ancient kings there were so pure and true

That round them every fragrant flower grew;

Cassia and pepper of the mountain-side

With melilotus white in clusters vied.

Two monarchs then, who high renown received,

Followed the kingly way, their goal achieved.

Two princes proud by lust their reign abused,

Sought easier path, and their own steps confused.

The faction for illict pleasure longed;

Dreadful their way where hidden perils thronged.

Danger against myself could not appal,

But feared I lest my sovereign's sceptre fall.

Forward and back I hastened in my quest,

Followed the former kings, and took no rest.

The prince my true integrity defamed,

Gave ear to slander, high his anger flamed;

Integrity I knew could not avail,

Yet still endured; my lord I would not fail.

Celestial spheres my witness be on high,

I strove but for his sacred majesty.

Twas first to me he gave his plighted word,

But soon repenting other counsel heard.

For me departure could arouse no pain;

I grieved to see his royal purpose vain.

Nine fields of orchids at one time I grew,

For melilot a hundred acres too,

And fifty acres for the azalea bright,

The rumex fragrant and the lichen white.

I longed to see them yielding blossoms rare,

And thought in season due the spoil to share.

I did not grieve to see them die away,

But grieved because midst weeds they did decay.

Insatiable in lust and greediness

The faction strove, and tired not of excess;

Themselves condoning, others they'd decry,

And steep their hearts in envious jealousy.

Insatiably they seized what they desired,

It was not that to which my heart aspired.

As old age unrelenting hurried near,

Lest my fair name should fail was all my fear.

Dew from magnolia leaves I drank at dawn,

At eve for food were aster petals borne;

And loving thus the simple and the fair,

How should I for my sallow features care?

With gathered vines I strung valeria white,

And mixed with blue wistaria petals bright,

And melilotus matched with cassia sweet,

With ivy green and tendrils long to meet.

Life I adapted to the ancient way,

Leaving the manners of the present day;

Thus unconforming to the modern age,

The path I followed of a bygone sage.

Long did I sigh and wipe away my tears,

To see my people bowed by griefs and fears.

Though I my gifts enhanced and curbed my pride,

At morn they'd mock me, would at eve deride;

First cursed that I angelica should wear,

Then cursed me for my melilotus fair.

But since my heart did love such purity,

I'd not regret a thousand deaths to die.

I marvel at the folly of the king,

So heedless of his people's suffering.

They envied me my mothlike eyebrows fine,

And so my name his damsels did malign.

Truly to craft alone their praise they paid,

The square in measuring they disobeyed;

The use of common rules they held debased;

With confidence their crooked lines they traced.

In sadness plunged and sunk in deepest gloom,

Alone I drove on to my dreary doom.

In exile rather would I meet my end,

Than to the baseness of their ways descend.

Remote the eagle spurns the common range,

Nor deigns since time began its way to change;

A circle fits not with a square design;

Their different ways could not be merged with mine.

Yet still my heart I checked and curbed my pride,

Their blame endured and their reproach beside.

To die for righteousness alone I sought,

For this was what the ancient sages taught.

I failed my former errors to discern;

I tarried long, but now I would return.

My steeds I wheeled back to their former way,

Lest all too long down the wrong path I stray.

On orchid-covered bank I loosed my steed,

And let him gallop by the flow'ry mead

At will. Rejected now and in disgrace,

I would retire to cultivate my grace.

With cress leaves green my simple gown I made,

With lilies white my rustic garb did braid.

Why should I grieve to go unrecognised,

Since in my heart fragrance was truly prized?

My headdress then high-pinnacled I raised,

Lengthened my pendents, where bright jewels blazed.

Others may smirch their fragrance and bright hues,

My innocence is proof against abuse.

Oft I looked back, gazed to the distance still,

Longed in the wilderness to roam at will.

Splendid my ornaments together vied,

With all the fragrance of the flowers beside;

All men had pleasures in their various ways,

My pleasure was to cultivate my grace.

I would not change, though they my body rend;

How could my heart be wrested from its end?

My handmaid fair, with countenance demure,

Entreated me allegiance to abjure:

"A hero perished in the plain ill-starred,

Where pigmies stayed their plumage to discard.

Why lovest thou thy grace and purity,

Alone dost hold thy splendid virtue high?

Lentils and weeds the prince's chamber fill:

Why holdest thou aloof with stubborn will?

Thou canst not one by one the crowd persuade,

And who the purpose of our heart hath weighed?

Faction and strife the world hath ever loved;

Heeding me not, why standest thou removed?"

I sought th'ancestral voice to ease my woe.

Alas, how one so proud could sink so low!

To barbarous south I went across the stream;

Before the ancient I began my theme:

"With odes divine there came a monarch's son,

Whose revels unrestrained were never done;

In antics wild, to coming perils blind,

He fought his brother, and his sway declined.

The royal archer, in his wanton chase

For foxes huge, his kingdom did disgrace.

Such wantonness predicts no happy end;

His queen was stolen by his loyal friend.

The traitor's son, clad in prodigious might,

In incest sinned and cared not what was right.

He revelled all his days, forgetting all;

His head at last in treachery did fall.

And then the prince, who counsels disobeyed,

Did court disaster, and his kingdom fade.

A prince his sage in burning cauldrons tossed;

His glorious dynasty ere long was lost.

"But stern and pious was their ancient sire,

And his successor too did faith inspire;

Exalted were the wise, the able used,

The rule was kept and never was abused.

The august heaven, with unbiassed grace,

All men discerns, and helps the virtuous race;

Sagacious princes through their virtuous deed

The earth inherit, and their reigns succeed.

The past I probed, the future so to scan,

And found these rules that guide the life of man:

A man unjust in deed who would engage?

Whom should men take as guide except the sage?

In mortal dangers death I have defied,

Yet could look back, and cast regret aside.

Who strove, their tool's defects accounting nought,

Like ancient sages were to cauldrons brought."

Thus I despaired, my face with sad tears marred,

Mourning with bitterness my years ill-starred;

And melilotus leaves I took to stem

The tears that streamed down to my garment's hem.

Soiling my gown, to plead my case I kneeled;

Th'ancestral voice the path to me revealed.

Swift jade-green dragons, birds with plumage gold,

I harnessed to the whirlwind, and behold,

At daybreak from the land of plane-trees grey,

I came to paradise ere close of day.

I wished within the sacred brove to rest,

But now the sun was sinking in the west;

The driver of the sun I bade to stay,

Ere with the setting rays we haste away.

The way was long, and wrapped in gloom did seem,

As I urged on to seek my vanished dream.

The dragons quenched their thirst beside the lake

Where bathed the sun, whilst I upon the brake

Fastened my reins; a golden bough I sought

To brush the sun, and tarred there in sport.

The pale moon's charioteer I then bade lead,

The master of the winds swiftly succeed;

Before, the royal blue bird cleared the way;

The lord of thunder urged me to delay.

I bade the phoenix scan the heaven wide;

But vainly day and night its course it tried;

The gathering whirlwinds drove it from my sight,

Rushing with lowering clouds to check my flight;

Sifting and merging in the firmament,

Above, below, in various hues they went.

The gate-keeper of heaven I bade give place,

But leaning on his door he scanned my face;

The day grew dark, and now was nearly spent;

Idly my orchids into wreaths I bent.

The virtuous and the vile in darkness merged;

They veiled my virtue, by their envy urged.

At dawn the waters white I left behind;

My steed stayed by the portals of the wind;

Yet, gazing back, a bitter grief I felt

That in the lofty crag no damsel dwelt.

I wandered eastward to the palace green,

And pendents sought where jasper boughs were seen,

And vowed that they, before their splendour fade,

As gift should go to grace the loveliest maid.

The lord of clouds I then bade mount the sky

To seek the steam where once the nymph did lie;

As pledge I gave my belt of splendid sheen,

My councillor appointed go-between.

Fleeting and wilful like capricious cloud,

Her obstinacy swift no change allowed.

At dusk retired she to the crag withdrawn,

Her hair beside the stream she washed at dawn.

Exulting in her beauty and her pride,

Pleasure she worshipped, and no whim denied;

So fair of form, so careless of all grace,

I turned to take another in her place.

To earth's extremities I sought my bride,

And urged my train through all the heaven wide.

Upon a lofty crag of jasper green

The beauteous princess of the west was seen.

The falcon then I bade entreat the maid,

But he, demurring, would my course dissuade;

The turtle-dove cooed soft and off did fly,

But I mistrusted his frivolity.

Like whelp in doubt, like timid fox in fear,

I wished to go, but wandered ever near.

With nuptial gifts the phoenix swiftly went;

I feared the prince had won her ere I sent.

I longed to travel far, yet with no bourn,

I could but wander aimless and forlorn.

Before the young king was in marriage bound,

The royal sisters twain might still be found;

My suit was unauspicious at the best;

I knew I had small hope in my request.

The world is dark, and envious of my grace;

They veil my virture and the evil praise.

Thy chamber dark lies in recesses deep,

Sagacious prince, risest thou not from sleep?

My zeal unknown the prince would not descry;

How could I bear this harsh eternity?

With mistletoe and herbs of magic worth,

I urged the witch the future to show forth.

"If two attain perfection they must meet,

But who is there that would thy virtue greet?

Far the nine continents their realm display;

Why here to seek thy bride doth thou delay?

Away!" she cried, "set craven doubt aside,

If beauty's sought, there's none hath with thee vied.

What place is there where orchids flower not fair?

Why is thy native land thy single care?

"Now darkly lies the world in twilight's glow,

Who doth your defects and your virtue know?

Evil and good herein are reconciled;

The crowd alone hath nought but is defiled.

With stinking mugwort girt upon their waist,

They curse the others for their orchids chaste;

Ignorant thus in choice of fragrance rare,

Rich ornaments how could they fitly wear?

With mud and filth they fill their pendent bag;

Cursing the pepper sweet, they brawl and brag."

Although the witches counsel I held good,

In foxlike indecision still I stood.

At night the wizard great made his descent,

And meeting him spiced rice I did present.

The angels came, shading with wings the sky;

From mountains wild the deities drew nigh.

With regal splendour shone the solemn sight,

And thus the wizard spake with omens bright:

"Take office high or low as days afford,

If one there be that could with thee accord;

Like ancient kings austere who sought their mate,

Finding the one who should fulfill their fate.

Now if thy heart doth cherish grace within,

What need is there to choose a go-between?

A convict toiled on rocks to expiate

His crime; his sovereign gave him great estate.

A butcher with his knife made roundelay;

His king chanced there and happy proved the day.

A prince who heard a cowherd chanting late

Raised him to be a councillor of state.

Before old age o'ertake thee on thy way,

Life still is young; to profit turn thy day.

Spring is but brief, when cuckoos start to sing,

And flowers will fade that once did spread and spring."

On high my jasper pendent proudly gleamed,

Hid by the crowd with leaves that thickly teemed;

Untiring they relentless means employed;

I feared it would through envy be destroyed.

This gaudy age so fickle proved its will,

That to what purpose did I linger still?

E'en orchids changed, their fragrance quickly lost,

And midst the weeds angelicas were tossed.

How could these herbs, so fair in former day,

Their hue have changed, and turned to mugworts grey?

The reason for their fall, not far to seek,

Was that to tend their grace their will proved weak.

I thought upon the orchids I might lean;

No flowers appeared, but long bare leaves were seen;

Their grace abandoned, vulgar taste to please,

Content with lesser flowers to dwell at ease.

To boasts and flattery the pepper turned;

To fill the pendent bag the dogwood yearned;

Thus only upon higher stations bent,

How could they long retain their former scent?

Since they pursued the fashion of the time,

Small wonder they decayed e'en in their prime.

Viewing the orchids' and the peppers' plight

Why blame the rumex and selinea white?

My jasper pendent rare I was beguiled

To leave, and to this depth then sank defiled.

It blossomed still and never ceased to grow;

Like water did its lovely fragrance flow:

Pleasure I took to wear this bough in sport,

As roaming wild the damsel fair I sought.

Thus in my prime, with ornaments bedecked,

I roved the earth and heaven to inspect.

With omens bright the seer revealed the way,

I then appointed an auspicious day.

As victuals rare some jasper twigs I bore,

And some prepared, provision rich to store;

Then winged horses to my chariot brought

My carriage bright with jade and ivory wrought.

How might tow hearts at variance accord?

I roamed till peace be to my mind restored.

The pillar of the earth I stayed beside;

The way was long, and winding far and wide.

In twilight glowed the clouds with wondrous sheen,

And chirping flew the birds of jasper green.

I went at dawn high heaven's ford to leave;

To earth's extremity I came at eve.

On phoenix wings the dragon pennons lay;

With plumage bright they flew to lead the way.

I crossed the quicksand with its treach'rous flood,

Beside the burning river, red as blood;

To bridge the stream my dragons huge I bade,

Invoked the emperor of the west to aid.

The way was long, precipitous in view;

I bade my train a different path pursue.

There where the heaven fell we turned a space,

And marked the western sea as meeting-place.

A thousand chariots gathred in my train,

With axles full abreast we drove amain;

Eight horses drew the carriages behind;

The pennons shook like serpents in the wind.

I lowered flags, and from my whip refrained;

My train of towering chariots I restrained.

I sang the odes. I trod a sacred dance,

In revels wild my last hour to enhance.

Ascending where celestial heaven blazed,

On native earth for the last time we gazed;

My slaves were sad, my steeds all neighed in grief,

And gazing back, the earth they would not leave.

Epilogue

Since in that kingdom all my virtue spurn,

Why should I for the royal city yearn?

Wide though the world, no wisdom can be found.

I'll seek the stream where once the sage was drowned.

The Fisherman

Ch':¹ Y:¹an, banished, wandered by the Tsanglang River. As he walked he recited poems. Haggard he looked and thin.

An old fisherman saw him, and asked: "Aren't you the knight Ch':¹ Y:¹an? What brought you to such a pass?"

"The crowd is dirty," said Ch':¹ Y:¹an, "I alone am clean. The crowd is drunk, I alone am sober. So I was banished."

"A wise man shouldn't be too particular," said the fisherman, "but should adapt himself to the times. If people are dirty, why don't you wallow with them in the mud? If people are drunk, why don't you drink a lot too? Why should you think so hard and hold so aloof that you were banished?"

Ch':¹ Y:¹an said: "They say, after you wash your hair you should brush your hat; after a bath you should shake your dress. How can a man sully his clean body with the dirt outside? I would rather jump into the river, and bury myself in the belly of the fish, than suffer my cleanliness to be sullied by the filth of the world!"

The old man smiled and paddled away, singing:

"When the river water's clear,

I can wash my tassels here.

Muddied, for such use unmeet,

Here I still can wash my feet."

This said, the old man went away.

CROSSING THE RIVER

Since I was young I have worn gorgeous dress

And still love raiment rare,

A long gem-studded sword hangs at my side,

And a tall hat I wear.

Bedecked with pearls that glimmer like the moon,

With pendent of fine jade,

Though there are fools who cannot understand,

I ride by undismayed.

Then give me green-horned serpents for my steed,

Or dragons white to ride,

In paradise with ancient kings I'd roam,

Or the world's roof bestride.

My life should thus outlast the universe,

With sun and moon supreme.

By southern savages misunderstood,

At dawn I ford the stream.

I gaze my last upon the river bank,

The autumn breeze blows chill.

I halt my carriage here within the wood

My steeds beside the hill.

In covered vessel travelling upstream,

The men bend to their oars;

The boat moves slowly, strong the current sweeps,

Nearby a whirlpool roars.

I set out from the bay at early dawn,

And reach the town at eve.

Since I am upright, and my conscience clear,

Why should I grieve to leave?

I linger by the tributary stream,

And know not where to go.

The forest stretches deep and dark around,

Where apes swing to and fro.

The beetling cliffs loom high to shade the sun,

Mist shrouding every rift,

With sleet and rain as far as eye can see,

Where low the dense clouds drift.

Alas! all joy has vanished from my life,

Alone beside the hill.

Never to follow fashion will I stoop,

Then must live lonely still.

One sage of old had head shaved like a slave,

Good ministers were killed,

In nakedness one saint was forced to roam,

Another's blood was spilled.

This has been so from ancient times till now,

Then why should I complain?

Unflinchingly I still shall follow truth,

Nor care if I am slain.

Refrain

Now, the phoenix dispossessed,

In the shrine crows make their nest.

Withered is the jasmine rare,

Fair is foul, and foul is fair,

Light is darkness, darkness day,

Sad at heart I haste away.

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |