Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy | |

|---|---|

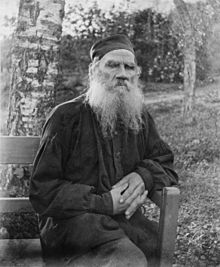

Leo Tolstoy in his later years. Early 20th century. | |

| Native name | Лев Николаевич Толстой |

| Born | Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy 9 September 1828 Yasnaya Polyana, Tula Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 20 November 1910 (aged 82) Astapovo, Ryazan Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Yasnaya Polyana |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, playwright, essayist |

| Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Period | 1847–1910 |

| Literary movement | Realism |

| Notable works | War and Peace Anna Karenina The Death of Ivan Ilyich The Kingdom of God Is Within You Resurrection |

| Spouse | Sophia Behrs (m. 1862) |

| Children | 14 |

| Signature | |

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy[note 1] (/ˈtoʊlstɔɪ,  listen); 9 September [O.S. 28 August] 1828 – 20 November [O.S. 7 November] 1910), usually referred to in English as Leo Tolstoy, was a Russian writer who is regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time.[2] He received multiple nominations for Nobel Prize in Literature every year from 1902 to 1906, and nominations for Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, 1902 and 1910, and his miss of the prize is a major Nobel prize controversy.[3][4][5][6]

listen); 9 September [O.S. 28 August] 1828 – 20 November [O.S. 7 November] 1910), usually referred to in English as Leo Tolstoy, was a Russian writer who is regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time.[2] He received multiple nominations for Nobel Prize in Literature every year from 1902 to 1906, and nominations for Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, 1902 and 1910, and his miss of the prize is a major Nobel prize controversy.[3][4][5][6]

Born to an aristocratic Russian family in 1828,[2] he is best known for the novels War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877),[7] often cited as pinnacles of realist fiction.[2] He first achieved literary acclaim in his twenties with his semi-autobiographical trilogy, Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852–1856), and Sevastopol Sketches (1855), based upon his experiences in the Crimean War. Tolstoy's fiction includes dozens of short stories and several novellas such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), Family Happiness (1859), and Hadji Murad (1912). He also wrote plays and numerous philosophical essays.

In the 1870s Tolstoy experienced a profound moral crisis, followed by what he regarded as an equally profound spiritual awakening, as outlined in his non-fiction work A Confession (1882). His literal interpretation of the ethical teachings of Jesus, centering on the Sermon on the Mount, caused him to become a fervent Christian anarchist and pacifist.[2] Tolstoy's ideas on nonviolent resistance, expressed in such works as The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894), were to have a profound impact on such pivotal 20th-century figures as Mahatma Gandhi[8] and Martin Luther King Jr.[9] Tolstoy also became a dedicated advocate of Georgism, the economic philosophy of Henry George, which he incorporated into his writing, particularly Resurrection (1899).

Contents

Origins

The Tolstoys were a well-known family of old Russian nobility who traced their ancestry to a mythical nobleman named Indris described by Pyotr Tolstoy as arriving "from Nemec, from the lands of Caesar" to Chernigov in 1353 along with his two sons Litvinos (or Litvonis) and Zimonten (or Zigmont) and a druzhina of 3000 people.[10][11] While the word "Nemec" has been long used to describe Germans only, at that time it was applied to any foreigner who didn't speak Russian (from the word nemoy meaning mute).[12] Indris was then converted to Eastern Orthodoxy under the name of Leonty and his sons – as Konstantin and Feodor, respectively. Konstantin's grandson Andrei Kharitonovich was nicknamed Tolstiy (translated as fat) by Vasily II of Moscow after he moved from Chernigov to Moscow.[10][11]

Because of the pagan names and the fact that Chernigov at the time was ruled by Demetrius I Starshy some researches concluded that they were Lithuanians who arrived from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[10][13][14] At the same time, no mention of Indris was ever found in the 14th – 16th-century documents, while the Chernigov Chronicles used by Pyotr Tolstoy as a reference were lost.[10] The first documented members of the Tolstoy family also lived during the 17th century, thus Pyotr Tolstoy himself is generally considered the founder of the noble house, being granted the title of count by Peter the Great.[15][16]

Life and career

Tolstoy was born at Yasnaya Polyana, a family estate 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) southwest of Tula, Russia, and 200 kilometres (120 mi) south of Moscow. He was the fourth of five children of Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy (1794–1837), a veteran of the Patriotic War of 1812, and Countess Mariya Tolstaya (née Volkonskaya; 1790–1830). After his mother died when he was two and his father when he was nine,[17] Tolstoy and his siblings were brought up by relatives.[2] In 1844, he began studying law and oriental languages at Kazan University, where teachers described him as "both unable and unwilling to learn."[17] Tolstoy left the university in the middle of his studies,[17] returned to Yasnaya Polyana and then spent much of his time in Moscow, Tula and Saint Petersburg, leading a lax and leisurely lifestyle.[2] He began writing during this period,[17] including his first novel Childhood, a fictitious account of his own youth, which was published in 1852.[2] In 1851, after running up heavy gambling debts, he went with his older brother to the Caucasus and joined the army. Tolstoy served as a young artillery officer during the Crimean War and was in Sevastopol during the 11-month-long siege of Sevastopol in 1854–55,[18] including the Battle of the Chernaya. During the war he was recognised for his bravery and courage and promoted to lieutenant.[18] He was appalled by the number of deaths involved in warfare,[17] and left the army after the end of the Crimean War.[2]

His conversion from a dissolute and privileged society author to the non-violent and spiritual anarchist of his latter days was brought about by his experience in the army as well as two trips around Europe in 1857 and 1860–61. Others who followed the same path were Alexander Herzen, Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. During his 1857 visit, Tolstoy witnessed a public execution in Paris, a traumatic experience that would mark the rest of his life. Writing in a letter to his friend Vasily Botkin: "The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens ... Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere."[19] Tolstoy's concept of non-violence or Ahimsa was bolstered when he read a German version of the Tirukkural.[20] He later instilled the concept in Mahatma Gandhi through his A Letter to a Hindu when young Gandhi corresponded with him seeking his advice.[21][22]

His European trip in 1860–61 shaped both his political and literary development when he met Victor Hugo, whose literary talents Tolstoy praised after reading Hugo's newly finished Les Misérables. The similar evocation of battle scenes in Hugo's novel and Tolstoy's War and Peace indicates this influence. Tolstoy's political philosophy was also influenced by a March 1861 visit to French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, then living in exile under an assumed name in Brussels. Apart from reviewing Proudhon's forthcoming publication, La Guerre et la Paix (War and Peace in French), whose title Tolstoy would borrow for his masterpiece, the two men discussed education, as Tolstoy wrote in his educational notebooks: "If I recount this conversation with Proudhon, it is to show that, in my personal experience, he was the only man who understood the significance of education and of the printing press in our time."

Fired by enthusiasm, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana and founded thirteen schools for the children of Russia's peasants, who had just been emancipated from serfdom in 1861. Tolstoy described the school's principles in his 1862 essay "The School at Yasnaya Polyana".[23] Tolstoy's educational experiments were short-lived, partly due to harassment by the Tsarist secret police. However, as a direct forerunner to A.S. Neill's Summerhill School, the school at Yasnaya Polyana[24] can justifiably be claimed the first example of a coherent theory of democratic education.

Personal life

The death of his brother Nikolay in 1860 had an impact on Tolstoy, and led him to a desire to marry.[17] On 23 September 1862, Tolstoy married Sophia Andreevna Behrs, who was sixteen years his junior and the daughter of a court physician. She was called Sonya, the Russian diminutive of Sofia, by her family and friends.[25] They had 13 children, eight of whom survived childhood:[26]

- Count Sergei Lvovich Tolstoy (1863–1947), composer and ethnomusicologist

- Countess Tatyana Lvovna Tolstaya (1864–1950), wife of Mikhail Sergeevich Sukhotin

- Count Ilya Lvovich Tolstoy (1866–1933), writer

- Count Lev Lvovich Tolstoy (1869–1945), writer and sculptor

- Countess Maria Lvovna Tolstaya (1871–1906), wife of Nikolai Leonidovich Obolensky

- Count Peter Lvovich Tolstoy (1872–1873), died in infancy

- Count Nikolai Lvovich Tolstoy (1874–1875), died in infancy

- Countess Varvara Lvovna Tolstaya (1875–1875), died in infancy

- Count Andrei Lvovich Tolstoy (1877–1916), served in the Russo-Japanese War

- Count Michael Lvovich Tolstoy (1879–1944)

- Count Alexei Lvovich Tolstoy (1881–1886)

- Countess Alexandra Lvovna Tolstaya (1884–1979)

- Count Ivan Lvovich Tolstoy (1888–1895)

The marriage was marked from the outset by sexual passion and emotional insensitivity when Tolstoy, on the eve of their marriage, gave her his diaries detailing his extensive sexual past and the fact that one of the serfs on his estate had borne him a son.[25] Even so, their early married life was happy and allowed Tolstoy much freedom and the support system to compose War and Peace and Anna Karenina with Sonya acting as his secretary, editor, and financial manager. Sonya was copying and hand-writing his epic works time after time. Tolstoy would continue editing War and Peace and had to have clean final drafts to be delivered to the publisher.[25][27]

However, their later life together has been described by A.N. Wilson as one of the unhappiest in literary history. Tolstoy's relationship with his wife deteriorated as his beliefs became increasingly radical. This saw him seeking to reject his inherited and earned wealth, including the renunciation of the copyrights on his earlier works.

Some of the members of the Tolstoy family left Russia in the aftermath of the 1905 Russian Revolution and the subsequent establishment of the Soviet Union, and many of Leo Tolstoy's relatives and descendants today live in Sweden, Germany, the United Kingdom, France and the United States. Among them are Swedish jazz singer Viktoria Tolstoy and the Swedish landowner Christopher Paus, whose family owns the major estate Herresta outside Stockholm.[28]

One of his great-great-grandsons, Vladimir Tolstoy (born 1962), is a director of the Yasnaya Polyana museum since 1994 and an adviser to the President of Russia on cultural affairs since 2012.[29][30] Ilya Tolstoy's great-grandson, Pyotr Tolstoy, is a well-known Russian journalist and TV presenter as well as a State Duma deputy since 2016. His cousin Fyokla Tolstaya (born Anna Tolstaya in 1971), daughter of the acclaimed Soviet Slavist Nikita Tolstoy (ru) (1923–1996), is also a Russian journalist, TV and radio host.[31]

Novels and fictional works

Tolstoy is considered one of the giants of Russian literature; his works include the novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina and novellas such as Hadji Murad and The Death of Ivan Ilyich.

Tolstoy's earliest works, the autobiographical novels Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852–1856), tell of a rich landowner's son and his slow realization of the chasm between himself and his peasants. Though he later rejected them as sentimental, a great deal of Tolstoy's own life is revealed. They retain their relevance as accounts of the universal story of growing up.

Tolstoy served as a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment during the Crimean War, recounted in his Sevastopol Sketches. His experiences in battle helped stir his subsequent pacifism and gave him material for realistic depiction of the horrors of war in his later work.[32]

His fiction consistently attempts to convey realistically the Russian society in which he lived.[33] The Cossacks (1863) describes the Cossack life and people through a story of a Russian aristocrat in love with a Cossack girl. Anna Karenina (1877) tells parallel stories of an adulterous woman trapped by the conventions and falsities of society and of a philosophical landowner (much like Tolstoy), who works alongside the peasants in the fields and seeks to reform their lives. Tolstoy not only drew from his own life experiences but also created characters in his own image, such as Pierre Bezukhov and Prince Andrei in War and Peace, Levin in Anna Karenina and to some extent, Prince Nekhlyudov in Resurrection.

War and Peace is generally thought to be one of the greatest novels ever written, remarkable for its dramatic breadth and unity. Its vast canvas includes 580 characters, many historical with others fictional. The story moves from family life to the headquarters of Napoleon, from the court of Alexander I of Russia to the battlefields of Austerlitz and Borodino. Tolstoy's original idea for the novel was to investigate the causes of the Decembrist revolt, to which it refers only in the last chapters, from which can be deduced that Andrei Bolkonsky's son will become one of the Decembrists. The novel explores Tolstoy's theory of history, and in particular the insignificance of individuals such as Napoleon and Alexander. Somewhat surprisingly, Tolstoy did not consider War and Peace to be a novel (nor did he consider many of the great Russian fictions written at that time to be novels). This view becomes less surprising if one considers that Tolstoy was a novelist of the realist school who considered the novel to be a framework for the examination of social and political issues in nineteenth-century life.[34] War and Peace (which is to Tolstoy really an epic in prose) therefore did not qualify. Tolstoy thought that Anna Karenina was his first true novel.[35]

After Anna Karenina, Tolstoy concentrated on Christian themes, and his later novels such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) and What Is to Be Done? develop a radical anarcho-pacifist Christian philosophy which led to his excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901.[36] For all the praise showered on Anna Karenina and War and Peace, Tolstoy rejected the two works later in his life as something not as true of reality.[37]

In his novel Resurrection, Tolstoy attempts to expose the injustice of man-made laws and the hypocrisy of institutionalized church. Tolstoy also explores and explains the economic philosophy of Georgism, of which he had become a very strong advocate towards the end of his life.

Tolstoy also tried himself in poetry with several soldier songs written during his military service and fairy tales in verse such as Volga-bogatyr and Oaf stylized as national folk songs. They were written between 1871 and 1874 for his Russian Book for Reading, a collection of short stories in four volumes (total of 629 stories in various genres) published along with the New Azbuka textbook and addressed to schoolchildren. Nevertheless, he was skeptical about poetry as a genre. As he famously said, "Writing poetry is like ploughing and dancing at the same time". According to Valentin Bulgakov, he criticised poets, including Alexander Pushkin, for their "false" epithets used "simply to make it rhyme".[38][39]

Critical appraisal by other authors

Tolstoy's contemporaries paid him lofty tributes. Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who died thirty years before Tolstoy's death, thought him the greatest of all living novelists. Gustave Flaubert, on reading a translation of War and Peace, exclaimed, "What an artist and what a psychologist!" Anton Chekhov, who often visited Tolstoy at his country estate, wrote, "When literature possesses a Tolstoy, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even when you know you have achieved nothing yourself and are still achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be, because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature." The 19th-century British poet and critic Matthew Arnold opined that "A novel by Tolstoy is not a work of art but a piece of life."[2]

Later novelists continued to appreciate Tolstoy's art, but sometimes also expressed criticism. Arthur Conan Doyle wrote "I am attracted by his earnestness and by his power of detail, but I am repelled by his looseness of construction and by his unreasonable and impracticable mysticism."[40] Virginia Woolf declared him "the greatest of all novelists."[2] James Joyce noted that "He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical!" Thomas Mann wrote of Tolstoy's seemingly guileless artistry: "Seldom did art work so much like nature." Vladimir Nabokov heaped superlatives upon The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Anna Karenina; he questioned, however, the reputation of War and Peace, and sharply criticized Resurrection and The Kreutzer Sonata.

Religious and political beliefs

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

After reading Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation, Tolstoy gradually became converted to the ascetic morality upheld in that work as the proper spiritual path for the upper classes: "Do you know what this summer has meant for me? Constant raptures over Schopenhauer and a whole series of spiritual delights which I've never experienced before. ... no student has ever studied so much on his course, and learned so much, as I have this summer"[41]

In Chapter VI of A Confession, Tolstoy quoted the final paragraph of Schopenhauer's work. It explained how the nothingness that results from complete denial of self is only a relative nothingness, and is not to be feared. The novelist was struck by the description of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu ascetic renunciation as being the path to holiness. After reading passages such as the following, which abound in Schopenhauer's ethical chapters, the Russian nobleman chose poverty and formal denial of the will:

In 1884, Tolstoy wrote a book called What I Believe, in which he openly confessed his Christian beliefs. He affirmed his belief in Jesus Christ's teachings and was particularly influenced by the Sermon on the Mount, and the injunction to turn the other cheek, which he understood as a "commandment of non-resistance to evil by force" and a doctrine of pacifism and nonviolence. In his work The Kingdom of God Is Within You, he explains that he considered mistaken the Church's doctrine because they had made a "perversion" of Christ's teachings. Tolstoy also received letters from American Quakers who introduced him to the non-violence writings of Quaker Christians such as George Fox, William Penn and Jonathan Dymond. Tolstoy believed being a Christian required him to be a pacifist; the consequences of being a pacifist, and the apparently inevitable waging of war by government, are the reason why he is considered a philosophical anarchist.

Later, various versions of "Tolstoy's Bible" would be published, indicating the passages Tolstoy most relied on, specifically, the reported words of Jesus himself.[43]

Tolstoy believed that a true Christian could find lasting happiness by striving for inner self-perfection through following the Great Commandment of loving one's neighbor and God rather than looking outward to the Church or state for guidance. His belief in nonresistance when faced by conflict is another distinct attribute of his philosophy based on Christ's teachings. By directly influencing Mahatma Gandhi with this idea through his work The Kingdom of God Is Within You (full text of English translation available on Wikisource), Tolstoy's profound influence on the nonviolent resistance movement reverberates to this day. He believed that the aristocracy were a burden on the poor, and that the only solution to how we live together is through anarchism.[citation needed]

He also opposed private property in land ownership[44] and the institution of marriage and valued the ideals of chastity and sexual abstinence (discussed in Father Sergius and his preface to The Kreutzer Sonata), ideals also held by the young Gandhi. Tolstoy's later work derives a passion and verve from the depth of his austere moral views.[45] The sequence of the temptation of Sergius in Father Sergius, for example, is among his later triumphs. Gorky relates how Tolstoy once read this passage before himself and Chekhov and that Tolstoy was moved to tears by the end of the reading. Other later passages of rare power include the personal crises that were faced by the protagonists of The Death of Ivan Ilyich, and of Master and Man, where the main character in the former or the reader in the latter are made aware of the foolishness of the protagonists' lives.

Tolstoy had a profound influence on the development of Christian anarchist thought.[46] The Tolstoyans were a small Christian anarchist group formed by Tolstoy's companion, Vladimir Chertkov (1854–1936), to spread Tolstoy's religious teachings. Philosopher Peter Kropotkin wrote of Tolstoy in the article on anarchism in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica:

During the Boxer Rebellion in China, Tolstoy praised the Boxers. He was harshly critical of the atrocities committed by the Russians, Germans, Americans, Japanese, and other western troops. He accused them of engaging in slaughter when he heard about the lootings, rapes, and murders, in what he saw as Christian brutality. Tolstoy also named the two monarchs most responsible for the atrocities; Nicholas II of Russia and Wilhelm II of Germany.[48][49] Tolstoy, a famous sinophile, also read the works of Chinese thinker and philosopher, Confucius.[50][51][52] Tolstoy corresponded with the Chinese intellectual Gu Hongming and recommended that China remain an agrarian nation and warned against reform like what Japan implemented.

The Eight-Nation Alliance intervention in the Boxer Rebellion was denounced by Tolstoy as were the Philippine–American War and the Second Boer War between the British Empire and the two independent Boer republics.[53] The words "terrible for its injustice and cruelty" were used to describe the Czarist intervention in China by Tolstoy.[54] Confucius's works were studied by Tolstoy. The attack on China in the Boxer Rebellion was railed against by Tolstoy.[55] The war against China was criticized by Leonid Andreev and Gorkey. To the Chinese people, an epistle, was written by Tolstoy as part of the criticism of the war by intellectuals in Russia.[56] The activities of Russia in China by Nicholas II were described in an open letter where they were slammed and denounced by Leo Tolstoy in 1902.[57] Tolstoy corresponded with Gu Hongming and they both opposed the Hundred Day's Reform by Kang Youwei and agreed that the reform movement was perilous.[58] Tolstoys' ideology on non violence shaped the anarchist thought of the Society for the Study of Socialism in China.[59] Lao Zi and Confucius's teachings were studied by Tolstoy. Chinese Wisdom was a text written by Tolstoy. The Boxer Rebellion stirred Tolstoy's interest in Chinese philosophy.[60] The Boxer and Boxer wars were denounced by Tolstoy.[61]

In hundreds of essays over the last 20 years of his life, Tolstoy reiterated the anarchist critique of the state and recommended books by Kropotkin and Proudhon to his readers, whilst rejecting anarchism's espousal of violent revolutionary means. In the 1900 essay, "On Anarchy", he wrote; "The Anarchists are right in everything; in the negation of the existing order, and in the assertion that, without Authority, there could not be worse violence than that of Authority under existing conditions. They are mistaken only in thinking that Anarchy can be instituted by a revolution. But it will be instituted only by there being more and more people who do not require the protection of governmental power ... There can be only one permanent revolution—a moral one: the regeneration of the inner man." Despite his misgivings about anarchist violence, Tolstoy took risks to circulate the prohibited publications of anarchist thinkers in Russia, and corrected the proofs of Kropotkin's "Words of a Rebel", illegally published in St Petersburg in 1906.[62]

Tolstoy was enthused by the economic thinking of Henry George, incorporating it approvingly into later works such as Resurrection (1899), the book that played a major factor in his excommunication.[63]

In 1908, Tolstoy wrote A Letter to a Hindu[64] outlining his belief in non-violence as a means for India to gain independence from British colonial rule. In 1909, a copy of the letter was read by Gandhi, who was working as a lawyer in South Africa at the time and just becoming an activist. Tolstoy's letter was significant for Gandhi, who wrote Tolstoy seeking proof that he was the real author, leading to further correspondence between them.[20]

Reading Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You also convinced Gandhi to avoid violence and espouse nonviolent resistance, a debt Gandhi acknowledged in his autobiography, calling Tolstoy "the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced". The correspondence between Tolstoy and Gandhi would only last a year, from October 1909 until Tolstoy's death in November 1910, but led Gandhi to give the name Tolstoy Colony to his second ashram in South Africa.[65] Besides nonviolent resistance, the two men shared a common belief in the merits of vegetarianism, the subject of several of Tolstoy's essays.[66]

Tolstoy also became a major supporter of the Esperanto movement. Tolstoy was impressed by the pacifist beliefs of the Doukhobors and brought their persecution to the attention of the international community, after they burned their weapons in peaceful protest in 1895. He aided the Doukhobors in migrating to Canada.[67] In 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, Tolstoy condemned the war and wrote to the Japanese Buddhist priest Soyen Shaku in a failed attempt to make a joint pacifist statement.

Towards the end of his life, Tolstoy become more and more occupied with the economic theory and social philosophy of Georgism.[68][69][70][71] He spoke of great admiration of Henry George, stating once that "People do not argue with the teaching of George; they simply do not know it. And it is impossible to do otherwise with his teaching, for he who becomes acquainted with it cannot but agree."[72] He also wrote a preface to George's Social Problems.[73] Tolstoy and George both rejected private property in land (the most important source of income of the passive Russian aristocracy that Tolstoy so heavily criticized) whilst simultaneously both rejecting a centrally planned socialist economy. Some assume that this development in Tolstoy's thinking was a move away from his anarchist views, since Georgism requires a central administration to collect land rent and spend it on infrastructure. However, anarchist versions of Georgism have also been proposed since.[74] Tolstoy's 1899 novel Resurrection explores his thoughts on Georgism in more detail and hints that Tolstoy indeed had such a view. It suggests the possibility of small communities with some form of local governance to manage the collective land rents for common goods; whilst still heavily criticising institutions of the state such as the justice system.

Death

Tolstoy died in 1910, at the age of 82. Just prior to his death, his health had been a concern of his family, who were actively engaged in his care on a daily basis. During his last few days, he had spoken and written about dying. Renouncing his aristocratic lifestyle, he had finally gathered the nerve to separate from his wife, and left home in the middle of winter, in the dead of night.[75] His secretive departure was an apparent attempt to escape unannounced from Sophia's jealous tirades. She was outspokenly opposed to many of his teachings, and in recent years had grown envious of the attention which it seemed to her Tolstoy lavished upon his Tolstoyan "disciples".

Tolstoy died of pneumonia[76] at Astapovo railway station, after a day's journey by train south.[77] The station master took Tolstoy to his apartment, and his personal doctors were called to the scene. He was given injections of morphine and camphor.

The police tried to limit access to his funeral procession, but thousands of peasants lined the streets. Still, some were heard to say that, other than knowing that "some nobleman had died", they knew little else about Tolstoy.[78]

According to some sources, Tolstoy spent the last hours of his life preaching love, non-violence, and Georgism to his fellow passengers on the train.[79]

In films

A 2009 film about Tolstoy's final year, The Last Station, based on the novel by Jay Parini, was made by director Michael Hoffman with Christopher Plummer as Tolstoy and Helen Mirren as Sofya Tolstoya. Both performers were nominated for Oscars for their roles. There have been other films about the writer, including Departure of a Grand Old Man, made in 1912 just two years after his death, How Fine, How Fresh the Roses Were (1913), and Leo Tolstoy, directed by and starring Sergei Gerasimov in 1984.

There is also a famous lost film of Tolstoy made a decade before he died. In 1901, the American travel lecturer Burton Holmes visited Yasnaya Polyana with Albert J. Beveridge, the U.S. senator and historian. As the three men conversed, Holmes filmed Tolstoy with his 60-mm movie camera. Afterwards, Beveridge's advisers succeeded in having the film destroyed, fearing that documentary evidence of a meeting with the Russian author might hurt Beveridge's chances of running for the U.S. presidency.[80]

Bibliography

See also

- Anarchism and religion

- Christian vegetarianism

- Leo Tolstoy and Theosophy

- List of peace activists

- Tolstoyan movement

- Henry David Thoreau

- War & Peace (2016 TV series)

Notes

References

- ^ "Tolstoy". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j "Leo Tolstoy". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ "Nomination Database". old.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "Proclamation sent to Leo Tolstoy after the 1901 year's presentation of Nobel Prizes". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Hedin, Naboth (1 October 1950). "Winning the Nobel Prize". The Atlantic. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "Nobel Prize Snubs In Literature: 9 Famous Writers Who Should Have Won (Photos)". Huffington Post. 7 October 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Beard, Mary (5 November 2013). "Facing death with Tolstoy". The New Yorker.

- ^ Martin E. Hellman, Resist Not Evil in World Without Violence (Arun Gandhi ed.), M.K. Gandhi Institute, 1994, retrieved on 14 December 2006

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther; Clayborne Carson; et al. (2005). The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume V: Threshold of a New Decade, January 1959 – December 1960. University of California Press. pp. 149, 269, 248. ISBN 978-0-520-24239-5.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Vitold Rummel, Vladimir Golubtsov (1886). Genealogical Collection of Russian Noble Families in 2 Volumes. Volume 2 // The Tolstoys, Counts and Noblemen. Saint Petersburg: A.S. Suvorin Publishing House, p. 487

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ivan Bunin, The Liberation of Tolstoy: A Tale of Two Writers, p. 100

- ^ Nemoy/Немой word meaning from the Dahl's Explanatory Dictionary (in Russian)

- ^ Troyat, Henri (2001). Tolstoy. ISBN 978-0-8021-3768-5.

- ^ Robinson, Harlow (6 November 1983). "Six Centuries of Tolstoys". The New York Times.

- ^ Tolstoy coat of arms by All-Russian Armorials of Noble Houses of the Russian Empire. Part 2, 30 June 1798 (in Russian)

- ^ The Tolstoys article from Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, 1890–1907 (in Russian)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f "Author Data Sheet, Macmillan Readers" (PDF). Macmillan Publishers Limited. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Ten Things You Didn't Know About Tolstoy". BBC.

- ^ A.N. Wilson, Tolstoy (1988), p. 146

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rajaram, M. (2009). Thirukkural: Pearls of Inspiration. New Delhi: Rupa Publications. pp. xviii–xxi.

- ^ Tolstoy, Leo (14 December 1908). "A Letter to A Hindu: The Subjection of India-Its Cause and Cure". The Literature Network. Retrieved 12 February 2012. The Hindu Kural

- ^ Parel, Anthony J. (2002), "Gandhi and Tolstoy", in M.P. Mathai; M.S. John; Siby K. Joseph (eds.), Meditations on Gandhi: a Ravindra Varma festschrift, New Delhi: Concept, pp. 96–112, retrieved 8 September 2012

- ^ Tolstoy, Lev N.; Leo Wiener; translator and editor (1904). The School at Yasnaya Polyana – The Complete Works of Count Tolstoy: Pedagogical Articles. Linen-Measurer, Volume IV. Dana Estes & Company. p. 227.

- ^ Wilson, A.N. (2001). Tolstoy. W.W. Norton. p. xxi. ISBN 978-0-393-32122-7.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Susan Jacoby, "The Wife of the Genius" (19 April 1981) The New York Times

- ^ Feuer, Kathryn B. Tolstoy and the Genesis of War and Peace, Cornell University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8014-1902-6

- ^ War and Peace and Sonya. uchicago.edu.

- ^ Nikolai Puzin, The Lev Tolstoy House-Museum In Yasnaya Polyana (with a list of Leo Tolstoy's descendants), 1998

- ^ Vladimir Ilyich Tolstoy at the official Yasnaya Polyana website

- ^ "Persons ∙ Directory ∙ President of Russia". President of Russia.

- ^ "Толстые / Телеканал "Россия – Культура"". tvkultura.ru.

- ^ Government is Violence: essays on anarchism and pacifism. Leo Tolstoy – 1990 – Phoenix Press

- ^ Tolstoy: the making of a novelist. E Crankshaw – 1974 – Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- ^ Tolstoy and the Development of Realism. G Lukacs. Marxists on Literature: An Anthology, London: Penguin, 1977

- ^ Tolstoy and the Novel. J Bayley – 1967 – Chatto & Windus

- ^ Church and State. L Tolstoy – On Life and Essays on Religion, 1934

- ^ Women in Tolstoy: the ideal and the erotic R.C. Benson – 1973 – University of Illinois Press

- ^ Leo Tolstoy (1874). Russian Book for Reading in 4 Volumes. Moscow: Aegitas, 381 pages

- ^ Valentin Bulgakov (2017). Diary of Leo Tolstoy's Secretary. Moscow: Zakharov, 352 pages, p. 29 ISBN 978-5-8159-1435-3

- ^ Doyle, Arthur Conan (January 1898). My Favourite Novelist and His Best Book. London. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ Tolstoy's Letter to A.A. Fet, 30 August 1869

- ^ Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. II, § 170

- ^ Orwin, Donna T. The Cambridge Companion to Tolstoy. Cambridge University Press, 2002

- ^ I Cannot Be Silent. Leo Tolstoy. Recollections and Essays, 1937.

- ^ editor on (8 September 2009). "Sommers, Aaron (2009) Why Leo Tolstoy Wouldn't Supersize It". Coastlinejournal.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ Christoyannopoulos, Alexandre (2009). The Contemporary Relevance of Leo Tolstoy's Late Political Thought. International Political Science Association. Tolstoy articulated his Christian anarchist political thought between 1880 and 1910, yet its continuing relevance should have become fairly self-evident already.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition. New York : Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 918. Anarchism

- ^ William Henry Chamberlin, Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, Ohio State University (1960). Michael Karpovich, Dimitri Sergius Von Mohrenschildt (ed.). The Russian review, Volume 19. Blackwell. p. 115.(Original from the University of Michigan)

- ^ Walter G. Moss (2008). An age of progress?: clashing twentieth-century global forces. Anthem Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84331-301-4.

- ^ Lukin, Alexander (2003). The Bear Watches the Dragon. ISBN 978-0-7656-1026-3.

- ^ Donna Tussing Orwin (2002). The Cambridge companion to Tolstoy. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-521-52000-3.

- ^ Derk Bodde (1950). Tolstoy and China. Princeton University Press. p. 25.(Original from the University of Michigan)

- ^ Apollon Davidson, Irina Filatova. The Russians and the Anglo Boer War. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, 1998. p. 181

- ^ Robert S. Cohen; J.J. Stachel; Marx W. Wartofsky (1974). For Dirk Struik: Scientific, Historical and Political Essays in Honour of Dirk J. Struik. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 606–. ISBN 978-90-277-0393-4.

- ^ Donna Tussing Orwin (2002). The Cambridge Companion to Tolstoy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-0-521-52000-3.

- ^ Mark Gamsa (2008). The Chinese Translation of Russian Literature: Three Studies. Brill. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-90-04-16844-2.

- ^ James Flath; Norman Smith (2011). Beyond Suffering: Recounting War in Modern China. UBC Press. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-0-7748-1957-2.

- ^ Khoon Choy Lee (2005). Pioneers of Modern China: Understanding the Inscrutable Chinese. World Scientific. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-981-256-618-8.

- ^ Heather M. Campbell (2009). The Britannica Guide to Political and Social Movements That Changed the Modern World. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-1-61530-016-7.

- ^ Derk Bodde (1967). Tolstoy and China. Johnson Reprint Corporation. pp. 25, 44, 107.

- ^ Leo Tolstoy; Leo Tolstoy (graf); Reginald Frank Christian (1978). Tolstoy's Letters: 1880–1910. Continuum International Publishing Group, Limited. p. 580. ISBN 978-0-485-71172-1.

- ^ Peter Kropotkin: From Prince to Rebel. G Woodcock, I Avakumović.1990.

- ^ Wenzer, Kenneth C. (1997). "Tolstoy's Georgist Spiritual Political Economy (1897–1910): Anarchism and Land Reform". The American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 56 (4, Oct): 639–667. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.1997.tb02664.x. JSTOR 3487337.

- ^ Parel, Anthony J. (2002), "Gandhi and Tolstoy", in M. P. Mathai; M.S. John; Siby K. Joseph (eds.), Meditations on Gandhi : a Ravindra Varma festschrift, New Delhi: Concept, pp. 96–112

- ^ Tolstoy and Gandhi, men of peace: a biography. MB Green – 1983 – Basic Books

- ^ Tolstoy, Leo (1892). "The First Step". Retrieved 21 May 2016. ... if [a man] be really and seriously seeking to live a good life, the first thing from which he will abstain will always be the use of animal food, because ... its use is simply immoral, as it involves the performance of an act which is contrary to the moral feeling – killing. Preface to the Russian translation of Howard William's The Ethics of Diet

- ^ Mays, H.G. "Resurrection:Tolstoy and Canada's Doukhobors." The Beaver 79.October/November 1999:38–44

- ^ Tolstoy: Principles For A New World Order, David Redfearn

- ^ "Tolstoy".

- ^ "Leo Tolstoy". Prosper Australia.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 30 May2015.

- ^ “A Great Iniquity,” letter to the London Times (1905)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 30 May2015.

- ^ Foldvary, Fred E. (15 July 2001). "Geoanarchism". anti-state.com. Retrieved 15 April2009.

- ^ The last days of Tolstoy. VG Chertkov. 1922. Heinemann

- ^ Leo Tolstoy. EJ Simmons – 1946 – Little, Brown and Company

- ^ Meek, James (22 July 2010). "James Meek reviews 'The Death of Tolstoy' by William Nickell, 'The Diaries of Sofia Tolstoy' translated by Cathy Porter, 'A Confession' by Leo Tolstoy, translated by Anthony Briggs and 'Anniversary Essays on Tolstoy' by Donna Tussing Orwin · LRB 22 July 2010". London Review of Books. pp. 3–8.

- ^ Tolstaya, S.A. The Diaries of Sophia Tolstoy, Book Sales, 1987; Chertkov, V. "The Last Days of Leo Tolstoy," http://www.linguadex.com/tolstoy/index.html, translated by Benjamin Scher

- ^ Kenneth C. Wenzer, "Tolstoy's Georgist spiritual political economy: anarchism and land reform – 1897–1910", Special Issue: Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Death of Henry George, The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Oct 1997; http://www.ditext.com/wenzer/tolstoy.html

- ^ Wallace, Irving, 'Everybody's Rover Boy', in The Sunday Gentleman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1965. p. 117.

Further reading

Craraft, James. Two Shining Souls: Jane Addams, Leo Tolstoy, and the Quest for Global Peace (Lanham: Lexington, 2012). 179 pp.

Lednicki, Waclaw (April 1947). "Tolstoy through American eyes". The Slavonic and East European Review. 25 (65).

Trotsky's 1908 tribute to Leo Tolstoy Published by the International Committee of the Fourth International (ICFI).

The Life of Tolstoy: Later years by Aylmer Maude, Dodd, Mead and Company, 1911 at Internet Archive

Why We Fail as Christians by Robert Hunter, The Macmillan Company, 1919 at Wikiquote

Why we fail as Christians by Robert Hunter, The Macmillan Company, 1919 at Google Books

External links

Leo Tolstoyat Wikipedia's sister projects

Media from Wikimedia Commons

Media from Wikimedia Commons

Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote

Texts from Wikisource

Texts from Wikisource

Data from Wikidata

Data from Wikidata

Leo Tolstoy at the Encyclopædia Britannica

Works by Leo Tolstoy at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about Leo Tolstoy at Internet Archive

Works by Leo Tolstoy at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Leo Tolstoy at the Internet Book List

Online project (readingtolstoy.ru) to create open digital version of 90 volumes of Tolstoy works

Leo Tolstoy on IMDb

"Tolstoy", BBC Radio 4 discussion with A.N. Wilson, Sarah Hudspith and Catriona Kelly (In Our Time, 25 April 2002)

Newspaper clippings about Leo Tolstoy in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

hide

v

t

e

Leo Tolstoy

Bibliography

Novels and

novellas

Childhood (1852)

Boyhood (1854)

Youth (1856)

Family Happiness (1859)

The Cossacks (1863)

War and Peace (1869)

Anna Karenina (1878)

The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886)

The Kreutzer Sonata (1889)

Resurrection (1899)

The Forged Coupon (1911)

Hadji Murat (1912)

Short stories

"The Raid" (1852)

"The Snowstorm" (1856)

"Albert" (1858)

"Three Deaths" (1859)

"God Sees the Truth, But Waits" (1872)

"The Prisoner of the Caucasus" (1872)

"What Men Live By" (1881)

"Quench the Spark" (1885)

"Where Love Is, God Is" (1885)

"Ivan the Fool" (1885)

"Wisdom of Children" (1885)

"The Three Hermits" (1886)

"Promoting a Devil" (1886)

"How Much Land Does a Man Need?" (1886)

"The Grain" (1886)

"Repentance" (1886)

"Croesus and Fate" (1886)

"Kholstomer" (1886)

"A Lost Opportunity" (1889)

"Master and Man" (1895)

"Too Dear!" (1897)

"Father Sergius" (1898)

"Work, Death, and Sickness" (1903)

"Three Questions" (1903)

"Alyosha the Pot" (1905)

"The Devil" (1911)

Plays

The Power of Darkness (1886)

The Light Shines in the Darkness (1890)

The Fruits of Enlightenment (1891)

The Living Corpse (1900)- Non-fiction

A Confession (1882)

The Gospel in Brief (1883)

What Is To Be Done? (1886)

The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894)

What Is Art? (1897)

"A Letter to a Hindu" (1908)

A Calendar of Wisdom (1910) - Family

Sophia (wife)

Alexandra (daughter)

Ilya (son)

Lev Lvovich (son)

Tatyana (daughter) - Life and legacy

Yasnaya Polyana

Tolstoyan movement

Christian anarchism

Departure of a Grand Old Man (1912 film)

The Last Station (1990 novel

2009 film)

Honors

Tolstoj quadrangle

crater

Related

The Triumph of the Farmer or Industry and Parasitism (1888)

Vladimir Chertkov