The Quaker Vocabulary of Tomorrow

December 1, 2021

Illustrations by jozefmicic.

Four Trends Changing Our Language

What changes might we see in Quaker language in the future? It’s impossible to know, of course, but I’ve been thinking about the trends we have seen in recent decades, and after a quick look into my crystal ball, I’m willing to make some predictions. I will discuss four specific trends and where I think they might be going, and then share some thoughts on how and when changes might take place.

1. More Nontheist Language

It’s easy to predict that Quaker language for discussing the Divine will change, because Quakers have been coining new terms and bringing new life to old images all along. It’s harder to predict which direction this will go. However, this is my guess: Liberal Quaker communities will continue to see an increase in ways of talking about spiritual experience and what happens in worship that do not assume that God is “out there,” or an external, all-powerful, or all-knowing deity. I expect that will include new ways of using old words, even “Spirit” and “God,” but there will be a need to find other images and create new metaphors. Possibilities include “heart,” “body-soul” (like “body-mind,” rejecting dualist approaches that split the human being into bits), and a revitalization of terms for “God within,” like “seed.” Hopefully, there are nontheist Quaker poets and prophets out there coining other beautiful and moving ways to express their perspectives.

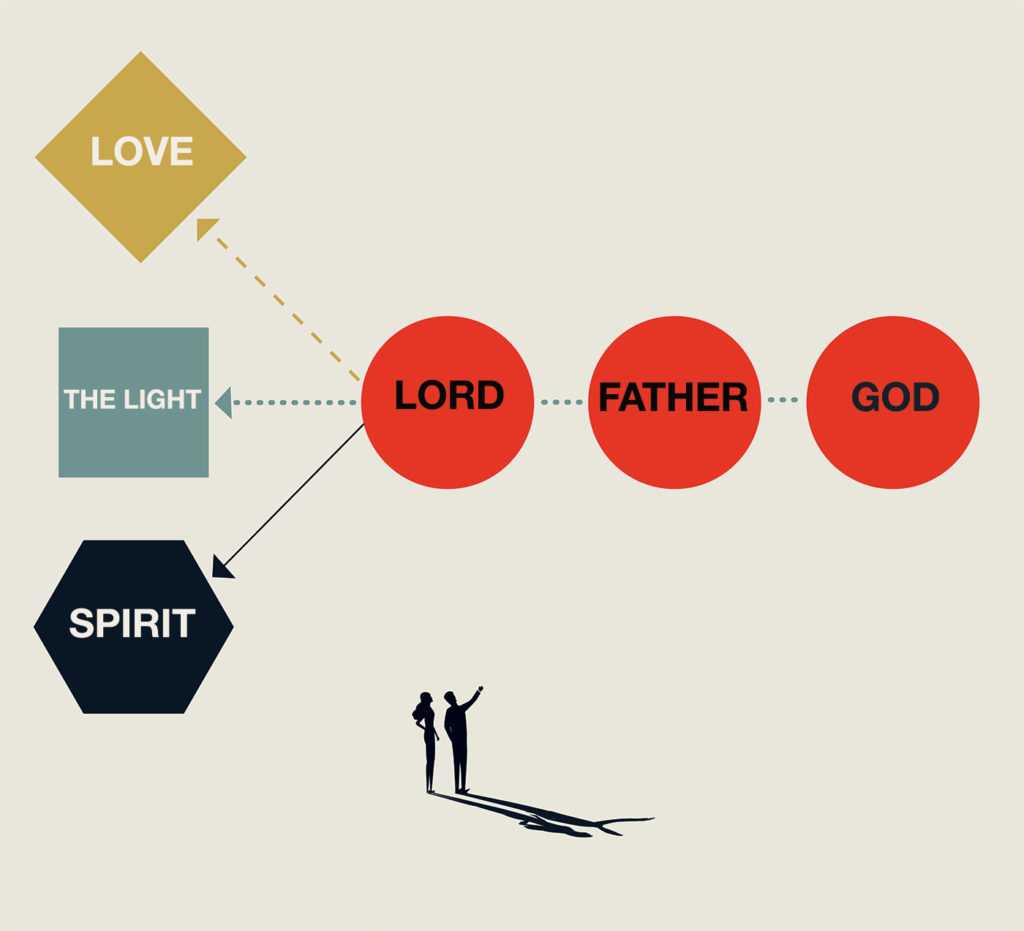

I don’t think this trend toward nontheist possibilities will ever result in a complete loss of explicitly monotheistic language from our collective texts. We have already seen moves away from problematic language about God: “the Light,” “Love,” or whatever you call it have reduced the use of masculine and power-based terms but not entirely removed them. “Lord” and “Father” may not be the modern preference in new writing (especially corporate work), but they still appear regularly, used by some individuals and in much-loved quotations from earlier writers. One way in which Quakers handle this diversity is a list of terms: “God, Love, Light, Spirit, Mother, Father, Parent, Child, Beloved, Allah, Heart, Comforter, Buddha-nature” with space left to add your own. If that trend continues, we may see both more and longer lists, and a change of the most common terms that appear there. (I explored lists of words for the Divine in my book Telling the Truth about God.)

2. Social Justice

Again, it’s easy to say that Quakers will continue to try to develop language that treats everyone as equals, and much harder to say what that will actually look like in the future. Sometimes our surrounding cultures get to this ahead of us, or by a different route (like using “you” rather than the early Quaker preference for “thou” for one person). It can also look different and proceed at different speeds in different places. Readers in the United States, where many Quaker communities dropped the word “overseer” in recent decades because of its association with the enslavement of people, may rightly be puzzled by the situation in Britain Yearly Meeting, where we are now in the middle of discussing what alternatives we might use. So I think Quakers everywhere will eventually stop using “overseer” and “elder,” and after a proliferation of other terms—ministry and counsel committee, pastoral care team, community development, etc.—we will eventually return to our biblical and Greek roots and call all these roles in our community “episcopal.” I’m joking about that bit, mostly. It’s more likely that the flowering of many terms will continue, with new phrases emerging as the sharing of responsibility changes in different communities, and that those of us who travel between Quaker groups, physically or online, will accept and often enjoy a process of constant learning.

As other issues come to the fore over time, our traditional language and widely used phrases can incorporate prejudices and social assumptions that are not true. There are many areas in which we still need to improve. The social implications of focusing on “Light” in a society that still privileges people with White skin and oppresses Black people and others with darker skin have been raised but not yet worked through in the Quaker community. The image of the “Inward Light” also draws on the experience of sighted people; it can be productive to work through metaphors that relate to other senses. Historically, Quakers have spoken about hearing, but thinking about how our spiritual lives involve touch, taste, proprioception (kinaesthesia), and other senses may provide interesting new ways of speaking. Similarly, we will need to think about how word choices and style of speaking and writing in Quaker contexts can be marked by social class, educational background, assumptions of monolingualism, and many other factors which contribute to social inequality.

3. Internationalization

Some Quakers have always communicated and traveled internationally. In recent years, the rise of Internet access (and most recently, the need to move more activities online because of the pandemic) has meant that contact with Quakers in other countries has become quicker and cheaper for many people. Quaker Facebook groups and Twitter hashtags are international, books of faith and practice and other documents from around the world can be found through a quick search, and visiting a meeting thousands of miles away is dramatically easier on Zoom. Not everyone chooses to engage in these ways, but the possibility is there for many more people, without needing to ask a meeting for help with funds or find time off work, etc. Internet tools help people find Quakers but aren’t necessarily geographically specific. Do you remember that Beliefnet quiz that told you what religion you should join? Quakers are actually my second result, below Unitarian Universalist, but although we have Unitarians in the UK, they are not identical to the Unitarian Universalists in the United States. This increases the potential for confusion when we have different terminology. It also increases opportunities for words or phrases commonly used in one community to be shared with another. For example, the phrase “way opens” is becoming more common among British Quakers due to increased contact with North American Quakers.

The worldwide Quaker family is more diverse than members of a particular yearly meeting sometimes realize, and first impressions (“They’re so different! Are they really Quakers?”) can be challenging and hurtful. Knowing more about another tradition brings disagreements to the fore, as well as increasing opportunities to share. Some words or phrases may not transfer well between cultures. Whatever direction this process moves in, however, increasing international contact online will likely shape changes in Quaker language in the next few decades.

4. Collective Pronouns

Individual third-person pronouns have been the focus of much media attention lately, as discussions about the use of singular “they” for nonbinary people and the need to respect pronoun changes for trans people have been normalized among welcoming and affirming communities, and contested by others. Quakers have historically wanted to use second-person pronouns more equally, too, although society as a whole settled on “you” for everyone rather than “thou.” But the pronouns I have in mind here are the first-person singular “I” and the plural “we.” Quakers traditionally write minutes and epistles in the first-person plural: we, the meeting, heard this, did that, decided the other. It’s also a convenient way for an individual to write about a group to which they belong, and if you look back through this article, you’ll see that I’ve done that. At Britain Yearly Meeting this year, though, we struggled with that, especially when we wanted to talk about issues that divide our community.

As a community that is mainly White, our communal body contains many people who need to reckon with White privilege, but we as a whole Quaker group cannot say, “We need to reckon with White privilege” without excluding the Friends of Color in our community who absolutely do not need to deal with White privilege any more. As different groups within Quaker communities continue to wrestle with these issues, I predict that we will need different approaches to gathering and to naming groups and subgroups in our records so that we can be honest and transparent about who we are, our collective failings and responsibilities, and the work we—as a whole or part of the community or as individuals—need to do.

When and how might these changes take place? In all of these areas, there is space for fresh and creative writing. Within specific Quaker communities, there is often a process of testing and gradually formalizing changes to language. We can see this by looking back a hundred years or so. I remember reading Rufus Jones for the first time, and not seeing anything special or different about his writing. But I was a century late to the conversation; things that were different and surprising when they were written had been taken up and made part of the canon. This happens in any community, but in a Quaker context in which a book of discipline or book of faith and practice is revised periodically, it is particularly apparent. So, as I’ve done in this article, we can look for clues for what is happening in individuals’ writing and in small groups, and guess what might happen in the future.

We may also want to take specific action. Language change can happen in such an organic way that it seems to be inevitable, and perhaps some of it is. It’s not clear to me that vowel shifts over time, for example, have a moral dimension. However, change in language can be deliberate, and many of the potential changes I’ve discussed do have moral aspects. Telling the truth (as we understand it) about ourselves and our spiritual experiences, creating a just society, learning from one another: how should we speak to these aims? Alongside other actions we need to take—for climate change, to end injustice, to build peace—we will need to explain our actions and reasons to people outside and inside our communities, and finding the words to do that is part of the process.

If you tell the whole truth about your experience of spirituality, of gender or race or disability, of being who you are in the world, what reactions do you get or fear you will get? Do you feel included in the Quaker “we” when your community, yearly meeting, or someone in Friends Journal writes in first-person plural? What could you learn from the way others speak, whether they are in another Quaker community or in the wider world? The social media practice of sharing or retweeting to amplify perspectives that might not otherwise be heard may be worth considering here. In Quaker decision-making processes, we aim to listen well enough not to need repetition, but in more general conversation, this sort of change to the way we communicate, as well as the language we use, could be the right move.

December 2021