My Interspiritual Compass

DECEMBER 29, 2022 BY GUDJON BERGMANN

Twenty-five years into my journey, I am still on the unbeaten path, the seeker I’ve always been. Compared with the early days of my journey, the biggest difference is that I now have a compass that allows me to explore without becoming lost or confused. I can walk the sturdy trails of religion or roam around in dense spiritual jungles without losing my bearings. All it takes is one look at my compass, and I immediately evoke all the fundamentals of syncretism, interfaith, and interspirituality.

Central Tenets

Central to this personal navigation system of mine—which I am only sharing for illustration purposes, not as an exercise in evangelism—are the experiential paths of Oneness and Goodness.

Oneness and My Affinity for Eastern Mysticism

For those who have read this publication, it should not come as a surprise that I am more attracted to the Oneness path, made evident by my meditation practice and affinity for Eastern mysticism. Early on, I was trying to escape the dysfunctional trauma of my childhood and quell the volatile nature of my unbridled passions, seeking a state of equilibrium where I would not be affected by highs or lows. Later, I stopped striving for permanency and learned to enjoy moments of peace instead. I’ve had many experiences of vastness, peace, calm, and tranquility in my meditation practice, affirming a nondual sense of I-am-ness. Such firsthand occurrences have created a sense of knowing that no amount of reading or philosophizing can ever generate.

Four Manifestations of Oneness

That being said, the contemplative or philosophical side of the Oneness path has also been quite rewarding. For instance, by discerning between four manifestations of Oneness, I’ve seen how spiritual seekers approach the idea from different perspectives. That understanding has helped me in my relationships with people of different faiths and provided me with clarity when reading modern and ancient texts.

1. Symbiotic Oneness

From a material perspective, symbiotic Oneness coincides with the realization that everything on our planet is interconnected, that we breathe the same air, use the same water, and are made of the same dust. Even though plenty of separation remains, such an understanding can have life-altering implications on everything from food consumption to how we treat each other. Symbiosis means that, like it or not, we are all in this together.

2. Unity

From an interpersonal perspective, unity implies a close relationship between two people—or one person and God—to the point where no separation is felt. I think of the Yin-Yang symbol in that context. Black and white are intertwined within a circle, so close that they seem like one, each with an aspect of the other embedded within. Yet, unity differs significantly from nonduality. The keyword to look for is ‘with.’ When people say they are ‘one with’ something, a degree of separation remains, however slight.

3. E = mc2

Energetic oneness is based on the concept that all matter came from the Big Bang, that all matter is energy, and that everything is interconnected. This definition most closely resembles my earliest spiritual experience of dissolving into light. It also supports the idea of eternal life. Energy is never destroyed; it only changes form. Take the example of a piece of wood thrown on a fire. Our senses tell us that the piece of wood has been destroyed, but upon closer inspection, we see that the wood has been transformed into ashes, heat, and air particulates. Those elements then turn into something else… and the cycle continues without end. Energy never dies and is interconnected, even though the senses detect separation.

4. Nonduality

Finally, nondual oneness speaks to our deepest sense of connection. The closest I have come to understanding nonduality is when I’ve compared it to space. The similarities are quite striking. Space exists separate from the objects in space. If I place an object in space, then space exists inside and outside the object. When I remove the object, space remains. If all objects are removed from space, then there is no up or down, no left or right, no back or forth… in essence, no duality. Therefore, the qualities of space are (i) it is always present, and (ii) it never changes, both of which are the ascribed characteristics of nonduality.

The Faces of Oneness

Many of my pagan and secular friends talk about Oneness in symbiotic terms. My traditionally religious friends, who revere an external aspect of God, usually speak of Oneness in unity terms. Our wording of choice in the New-Age movement was energetic Oneness, and mystics of all traditions describe a sense of nonduality in a similar way; that is, they don’t have many words for it.

Accepting Goodness as Equal

Because the Oneness path informed my spiritual route of choice since I was first introduced to Eastern thought, especially the energetic and nondual approaches, I have to admit that it took much longer for me to accept the equal importance of the Goodness path. When compared to unveiling the essence of who I am, then following moral maxims, recounting stories and myths, going through rituals, and observing cultural traditions often seemed too dualistic and shallow, not spiritual enough.

However, the longer I slogged through life with all its ups and downs, the more people I interacted with from a variety of faiths, and the more suffering I saw in the world, the more my appreciation for the Goodness path grew.

Direction and Meaning

Studying the world’s religions and consorting with people of all faiths has shown me that worshipping God, nurturing the internal seeds of altruism, following moral teachings, congregating, praying, and ritualizing the cycles of life has given us, mere mortals, direction and meaning for millennia.

Making Peace With Restrictions

Even the restrictions I railed against in my youth made more sense, especially after reading this passage by Huston Smith.

“Jealousies, hatreds, and revenge can lead to violence that, unless checked, rips communities to pieces. Murder instigates blood feuds that drag on indefinitely. Sex, if it violates certain restraints, can rouse passions so intense as to destroy entire communities. Similarly with theft and prevarication. We can imagine societies in which people do exactly as they please on these counts, but none have been found and anthropologists have now covered the globe. Apparently, if total permissiveness has ever been tried, its inventors have not survived for anthropologists to study.”

My life has undoubtedly benefitted from having reins.

Essential to Moral Development

All the same, the significance of the Goodness path was not cemented in my mind until I realized that moral development—with its focus on an ever-increasing ability to care for others—was at the heart of the Goodness path—exemplified by moral codes and altruistic aspirations—and central to my own life. This meant that I had been on the Goodness path for decades, even though I had never acknowledged it as such.

Aha Moments

My late life “discovery” may seem as obvious as the nose on my face, but it still represented an important revelation. I had tried to push morality aside, both in my rebellious youth and as a nondual spiritual aspirant. Yet, I wanted to be kind and care for others, wanted to increase my capacity for compassion, and wanted to be a better man.

Accepting this reality led to several other realizations.

1. Care is Limited

First, care is limited by the amount of energy, money, and time I’ve had to spare. My primary resources are time and energy. Because both are limited, I’ve had to pick and choose what I focus on.

2. Actions Speak Louder Than Words

Second, and in line with the first, actions speak louder than words. Nothing has taught me more about caring for another human being than being a stay-at-home father. Parenting would be easy if predicated on good intentions and pleasant thoughts. Everyone “believes” that he or she will do a good job until the rubber hits the road.

Being the primary caretaker has taught me that unconditional caring is being there even when loving emotions are not, that I need to put selfish desires aside for the benefit of my children, and that I need to show up in all my imperfect glory, ready to help, nurture, and support, no matter the circumstances.

Before I was in the stay-at-home role, I took pride in helping others. It felt great to be the person everyone looked to for guidance in my workshops and seminars, especially in controlled environments where I could show only the good sides of myself. At home, however, pretenses are removed. I’ve been more emotionally naked dealing with my teenage son during his rebellious mood swings and tending to my tween daughter when she feels overwhelmed than at any other time in my life. My kids know that I love them dearly, but they also know that I am fallible, and that is okay.

3. Attraction Can Lead to Repulsion

Third, I had to reevaluate my connection with the Eastern concepts of raga (attraction) and dwesha (repulsion). On the nondual Oneness path, the goal was to rise above such dualistic feelings and find perfect equanimity. On the dualistic Goodness path, however, the goal was to focus more on attraction and less on repulsion. As I saw it, the problem was that a strong attraction often created an equally strong repulsion, consciously or unconsciously.

Love for one thing could easily turn into hate for another. People could start with good intentions, attracted by certain approaches to life, but then turn around and spend all their time railing against those who did the opposite, creating what some have called ‘the religion of hate.’

Once I recognized this dualistic rubber-band tendency, I started working on mitigating and tempering my feelings of repulsion. For instance, it would have been all too easy to allow my affinity for sobriety to turn into disdain for drinkers or my preference for marital fidelity to become a harsh judgment of infidelity. Instead, I remind myself why I don’t drink or cheat—mainly because both of those behaviors caused tremendous pain in my life and the lives of others—and make an effort to show compassion for those who are still caught in the web.

The attraction vs. repulsion paradigm reminds me that despising others will not make me a better person.

4. My Ethics Are Rooted in Christianity

Fourth, although substantial parts of my value system have come from psychology, Eastern mysticism, and my ability to think through the consequences of my actions, most of my ethical standards are rooted in my Christian upbringing.

Love thy neighbor as thyself, turn the other cheek, judge not lest ye be judged, know people by the fruits of their actions, seek and ye shall find, what you have done unto the least of these you have done unto me… and so on. All of those teachings are still perfectly valid. Seeing their manifestation in the lives of people like Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Mr. Rogers, Norman Vincent Peale, and Dr. Albert Schweitzer (to name a few) has provided me with tremendous inspiration over the years. I still don’t call myself a Christian, but it makes no sense to discard the cultural tradition I was raised in completely.

Balancing Oneness and Goodness

As things stand today, the Goodness path has earned its rightful place alongside the Oneness path in my life. I feel like the two balance each other out. When I detach too much, it can lead to indifference and apathy. To counter that, I turn to service and invest myself in this world. Compassion grounds me. On the other hand, when I am too heavily invested in the Goodness path, especially when I am advocating for a particular outcome in the world that I have no control over, I back off, detach and settle into a sense of serenity. Thich Nhat Hanh worded this dance between compassion and inner peace beautifully.

“Someone asked me, “Aren’t you worried about the state of the world?” I allowed myself to breathe and then said, “What is most important is not to allow your anxiety about what happens in the world to fill your heart. If your heart is filled with anxiety, you will get sick, and you will not be able to help.”

Two More Components of the Compass

The paths of Oneness and Goodness are so inclusive that I could easily have stopped there when constructing my interspiritual compass. Still, I decided to cushion it with two more components.

First, I added Wilber’s four quadrants (I, We, It, and Its). That model reminds me to look at everything from more than one angle and include the subjective personal point of view, the cultural perspective, and scientific facts.

Second, I incorporated the four classical paths of yoga (Gnana, Karma, Bhakti, and Raja) and their emphasis on a wide range of spiritual practices, including meditative experimentation, philosophical contemplation, devotion, love, service, and non-attachment, all of which have been instrumental in my life.

Symbols Exist for a Reason

Early in my spiritual journey, I developed a real antipathy for symbols. They were too vague in my mind, too open to subjective interpretation. I wanted to clarify everything with words and precise definitions.

Over time, however, I realized that symbols exist for a reason. For example, I once tried to extract everything the OM symbol could mean, and the stream of words it produced seemed never-ending.

“OM/AUM: The primal sound, the origin of all languages, holy vibration or holy trinity. AUM is everything. A represents the material world. U represents the astral world. M represents the causal world. All trinities can be found within AUM, such as Brahma-Vishnu-Shiva, past-present-future, creation-maintenance-transformation, waking-dreaming-deep sleep, father-son-holy ghost, tamas-rajas-sattva, body-mind-spirit, sat-chit-ananda, material world-astral world-causal world.”

My conclusion was that I could either say all of those things in one go or use the OM symbol and then slowly populate it with my understanding. I chose the latter.

I went through a similar process with the chakra system. First, I simplified each chakra into one word. Then, I added longer definitions for clarity. Finally, after the word clouds became too expansive, I reverted to the color spectrum of the rainbow as a symbolic representation.

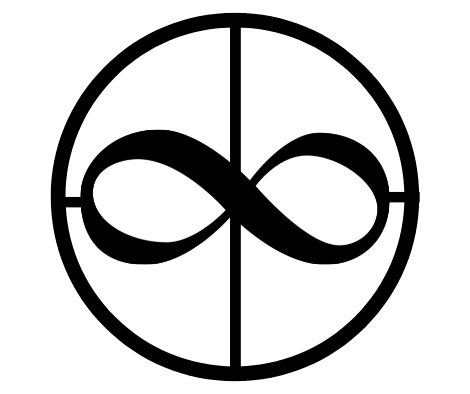

Symbolizing My Compass

Based on those experiments, I decided that it would probably be wise for me to symbolize my compass. My thinking was reasonably straightforward and combined the following three elements.Infinity symbol: In Vedanta, the infinity symbol signifies Brahman and the eternal dance between nonduality and duality. To me, it symbolizes the paths of Oneness and Goodness.

Circle: The circle represents the confines of human life and the circle of nature into which we are born. It also signifies the essential sameness of zero and infinity, macrocosm and the microcosm, the drop and the ocean.

Lines/Chambers: The four lines that create the chambers within the circle are symbolic of the four quadrants (I, We, It and Its) and the four yoga practices (Raja, Jnana, Karma, and Bhakti).

The outcome is my personal compass—a visual representation that works for me. It summons all the right ideas and sentiments in my mind. With one glance, I see the practices and philosophies that have served me well to date. Better yet, the symbol prompts me to acknowledge similar practices and beliefs across other traditions.

* This article was curated from my memoir titled Spiritual in My Own Way

Gudjon Bergmann

Author, Coach, and Mindfulness Teacher

Amazon Author Profile

Recommended books:Monk of All Faiths: Inspired by The Prophet (fiction)

Spiritual in My Own Way (memoir)

Co-Human Harmony: Using Our Shared Humanity to Bridge Divides (nonfiction)

Experifaith: At the Heart of Every Religion (nonfiction)

Premature Holiness: Five Weeks at the Ashram (novel)

The Meditating Psychiatrist Who Tried to Kill Himself (novel)