메멘토 모리

메멘토 모리(Memento mori)는 "자신의 죽음을 기억하라" 또는 "너는 반드시 죽는다는 것을 기억하라", "네가 죽을 것을 기억하라"를 뜻하는 라틴어 낱말이다.

고대 로마에서는 원정에서 승리를 거두고 개선하는 장군이 시가 행진을 할 때 노예를 시켜 행렬 뒤에서 큰소리로 외치게 했다고 한다. "메멘토 모리!" [Memento Mori!] 라틴어로 '죽음을 기억하라'라는 뜻인데, '전쟁에서 승리했다고 너무 우쭐대지 말라. 오늘은 개선 장군이지만, 너도 언젠가는 죽는다. 그러니 겸손하게 행동하라.' 이런 의미에서 생겨난 풍습이라고 한다.

한편 이러한 맥락에서 17세기 네덜란드 정물화 화풍인 바니타스화풍도 영향받았다고 여겨진다.[1]

나바호 인디언의 메멘토 모리[편집]

나바호족에게서도 이와같은 "메멘토 모리"의 이야기를 들을 수 있다. "네가 세상에 태어날 때 너는 울었지만 세상은 기뻐했으니, 네가 죽을 때 세상은 울어도 너는 기뻐할 수 있도록 그런 삶을 살아라."[2]

같이 보기[편집]

각주[편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다. |

- ↑ 17세기네델란드이야기,냉이꽃

- ↑ 중앙일보-[윌셔 플레이스 '메멘토 모리'의 삶,[LA중앙일보] 발행 2014/03/11 미주판 23면 ]

메멘트 모리

메멘트 모리 ( 라 : memento mori )는 라틴어로 " 자신이 언젠가 반드시 죽는 것을 잊지 말라" " 사람에게 방문하는 죽음을 잊지 말아라 "라는 의미의 경구. 예술 작품의 모티브로 널리 사용된다.

역사 [ 편집 ]

고대 로마 에서는 " 장군 이 개선 식 퍼레이드를 했을 때 사용되었다"고 전해진다. 장군 뒤에 서 있는 하인은 “장군은 오늘 절정에 있지만 내일은 그럴지 모르겠다”는 계명을 상기시키는 역할을 담당하고 있었다. 거기서, 사용인은 「메멘토 모리」라고 말함으로써, 그것을 생각하게 하고 있었다.

그러나 고대에서는 그다지 널리 사용되지 않았다. 당시 '메멘트 모리'의 취지는 carpe diem ( 지금을 즐길 수 있다 )는 것으로 '먹고 마시고 쾌활해지자. 우리는 내일 죽으니까'라는 조언이었다. 호라티우스 의 시에는 " Nunc est bibendum, nunc pede libero pulsanda tellus. "(지금은 마셔야 한다.

이 말은 그 후 기독교 세계에서 다른 의미를 갖게 되었다. 천국 , 지옥 , 영혼 의 구제가 중요시됨에 따라 죽음이 의식의 전면에 나왔기 때문이다. 기독교 예술 작품에서 "메멘토 모리"는 거의이 맥락에서 사용됩니다. 기독교 문맥에서 '메멘트 모리'는 nunc est bibendum 과는 반대의 상당히 덕화된 의미로 사용되게 되었다. 기독교인들에게는 죽음에 대한 생각은 현세에서의 즐거움, 사치, 수술이 공허하고 어리석은 것임을 강조하는 것이었고, 내세를 생각하게 하는 유인이 되었다.

교토학파 의 철학자로 알려진 타나베 모토 는 지난 밤에 '죽음의 철학(死の弁証法)'이라는 철학을 구상했다. 그 철학의 개략을 나타내기 위해 발표된 논문이 '메멘토모리'라고 제목이 붙여져 있다. 타나베는 이 논문 속에서 현대를 '죽음의 시대'로 규정했다. 근대인이 살기의 쾌락과 기쁨을 무반성에 계속 추구한 결과, 삶을 풍요롭게 할 과학기술이 오히려 인간의 삶을 위협한다는 자기모순적 사태를 초래해 현대인을 니히리즘에 몰아 넣어 라는 것이다. 타나베는 이 궁상을 타파하기 위해 메멘트 모리의 계고(「죽음을 잊지 말라」)에 되돌아가야 한다고 주장한다[1 ] .

관련 작품 [ 편집 ]

- 묘석

- 부패한 시체를 표현한 무덤 ( 트랜지 )은 15세기 에 유럽의 부유계급 사이에서 유행했다.

- ' 죽음의 무도 '는 '메멘트 모리'의 가장 알려진 주제로 사신이 가난한 사람과 부자를 똑같이 데리고 있어, 이것은 유럽 의 많은 교회에 장식되었다. 그 후의 식민지 시대의 미국 에서도 퓨리탄 의 무덤에는 날개를 가진 두개골, 해골 , 촛불을 끄는 천사가 그려져 있다.

- 정물화

- 예술에서 ' 정물화 '는 이전에 ' 바니타스 '( 라 : vanitas , '공허')로 불렸다. 정물화를 그릴 때에는 어쨌든 죽음을 연상시키는 심볼을 그려야 한다고 생각되었기 때문이다. 분명히 죽음을 의미하는 해골(두개골)이나, 보다 섬세한 표현으로서는 꽃잎이 떨어지고 있는 꽃 등이, 잘 심볼로서 사용되고 있었다.

- 사진

- 사진 이 발명되었을 때, 친족의 시체를 사진으로 기록하는 것이 유행했다.

- 시계

- 시계 는 "현세의 시간이 점점 적어져 가는 것을 나타내는 것"이라고 생각되고 있었다. 공공 시계에는, ultima forsan (의에 의하면, 마지막 <의 시간>)이나 vulnerant omnes, ultima necat (모두 상처를 입히고, 마지막은 죽는다)라는 명이 찍혀 있었다. 현대에서는 tempus fugit (광음야의 과시)의 명이 쳐지는 경우가 많다. 독일 의 아우크스부르크 에 있는 유명한 카라쿠리 시계는 '사신이 시간을 친다'는 것이다. 스코틀랜드 여왕 메리 는 은의 두개골의 형태로 표면에 호라티우스 시의 한 문장이 장식 된 큰 회중 시계를 가지고 있었다 [ 2 ] .

- 문학

- 영국 의 작품에서는 토마스 브라운 의 ' Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial '과 제레미 테일러의 '성스러운 삶, 거룩한 죽음'이 있다. 또, 토마스 그레이의 「Elegy in a Country Churchyard」나 에드워드 영의 「Night Thoughts」도, 이 테마를 다루고 있다.

각주 [ 편집 ]

- ^ 타나베 모토 (1964 (1957)) "메멘토 모리", "타나베 모토 전집 제 13 권", pp165-175, 쓰쿠마 서방

- ^ “ 'Memento mori' watch in the form of a skull, known as the 'Mary Queen of Scots' watch. ”. Science Museum Group. 2022년 9월 11일에 확인함.

참고 문헌 [ 편집 ]

- 존 핀레이의 '1권으로 학위 미술사' 2021년, 246쪽, ISBN 978-4-315-52484-0

관련 항목 [ 편집 ]

- 그 날을 따라 ( Carpe diem )

- 때는 날아간다 ( Tempus fugit )

- 바니 타스 ( Vanitas )

- 사생학

- 바로크

- 메멘토모리

- 물건의 아레레

- 무상

- 장례 예술

- Category:사생관

- Category:죽음과 문화

외부 링크 [ 편집 ]

- 메멘토모리란? - 코트뱅크

- 메멘트 모리란 ? - 단편 소설 작품명 Weblio 사전

- 죽음을 생각하는 건 - 코트뱅크

Memento mori

Memento mori (Latin for 'remember that you [have to] die'[2]) is an artistic or symbolic trope acting as a reminder of the inevitability of death.[2] The concept has its roots in the philosophers of classical antiquity and Christianity, and appeared in funerary art and architecture from the medieval period onwards.

The most common motif is a skull, often accompanied by one or more bones. Often this alone is enough to evoke the trope, but other motifs such as a coffin, hourglass and wilting flowers signify the impermanence of human life. Often these function within a work whose main subject is something else, such as a portrait, but the vanitas is an artistic genre where the theme of death is the main subject. The Danse Macabre and Death personified with a scythe as the Grim Reaper are even more direct evocations of the trope.

Pronunciation and translation[edit]

In English, the phrase is typically pronounced /məˈmɛntoʊ ˈmɔːri/, mə-MEN-toh MOR-ee. It is reconstructed as ideally pronounced as something like [mɛˈmɛntoː ˈmɔriː] if spoken by an ancient Roman around the beginning of the AD era.[citation needed]

Memento is the 2nd person singular active imperative of meminī, 'to remember, to bear in mind', usually serving as a warning: "remember!" Morī is the present infinitive of the deponent verb morior 'to die'.[3]

In other words, "remember death" or "remember that you die".[4]

History of the concept[edit]

In classical antiquity[edit]

The philosopher Democritus trained himself by going into solitude and frequenting tombs.[5] Plato's Phaedo, where the death of Socrates is recounted, introduces the idea that the proper practice of philosophy is "about nothing else but dying and being dead".[6]

The Stoics of classical antiquity were particularly prominent in their use of this discipline, and Seneca's letters are full of injunctions to meditate on death.[7] The Stoic Epictetus told his students that when kissing their child, brother, or friend, they should remind themselves that they are mortal, curbing their pleasure, as do "those who stand behind men in their triumphs and remind them that they are mortal".[8] The Stoic Marcus Aurelius invited the reader (himself) to "consider how ephemeral and mean all mortal things are" in his Meditations.[9][10]

In some accounts of the Roman triumph, a companion or public slave would stand behind or near the triumphant general during the procession and remind him from time to time of his own mortality or prompt him to "look behind".[11] A version of this warning is often rendered into English as "Remember, Caesar, thou art mortal", for example in Fahrenheit 451.

In Judaism[edit]

Several passages in the Old Testament urge a remembrance of death. In Psalm 90, Moses prays that God would teach his people "to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom" (Ps. 90:12). In Ecclesiastes, the Preacher insists that "It is better to go to the house of mourning than to go to the house of feasting, for this is the end of all mankind, and the living will lay it to heart" (Eccl. 7:2). In Isaiah, the lifespan of human beings is compared to the short lifespan of grass: "The grass withers, the flower fades when the breath of the LORD blows on it; surely the people are grass" (Is. 40:7).

In early Christianity[edit]

The expression memento mori developed with the growth of Christianity, which emphasized Heaven, Hell, and salvation of the soul in the afterlife.[12] The 2nd-century Christian writer Tertullian claimed that during his triumphal procession, a victorious general would have someone (in later versions, a slave) standing behind him, holding a crown over his head and whispering "Respice post te. Hominem te memento" ("Look after you [to the time after your death] and remember you're [only] a man."). Though in modern times this has become a standard trope, in fact no other ancient authors confirm this, and it may have been Christian moralizing rather than an accurate historical report.[13]

In Europe from the medieval era to the Victorian era[edit]

Christian Theology[edit]

The thought was then utilized in Christianity, whose strong emphasis on divine judgment, heaven, hell, and the salvation of the soul brought death to the forefront of consciousness.[14] In the Christian context, the memento mori acquires a moralizing purpose quite opposed to the nunc est bibendum (now is the time to drink) theme of classical antiquity. To the Christian, the prospect of death serves to emphasize the emptiness and fleetingness of earthly pleasures, luxuries, and achievements, and thus also as an invitation to focus one's thoughts on the prospect of the afterlife. A Biblical injunction often associated with the memento mori in this context is In omnibus operibus tuis memorare novissima tua, et in aeternum non peccabis (the Vulgate's Latin rendering of Ecclesiasticus 7:40, "in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin.") This finds ritual expression in the rites of Ash Wednesday, when ashes are placed upon the worshipers' heads with the words, "Remember Man that you are dust and unto dust, you shall return."

Memento mori has been an important part of ascetic disciplines as a means of perfecting the character by cultivating detachment and other virtues, and by turning the attention towards the immortality of the soul and the afterlife.[15]

Architecture[edit]

The most obvious places to look for memento mori meditations are in funeral art and architecture. Perhaps the most striking to contemporary minds is the transi or cadaver tomb, a tomb that depicts the decayed corpse of the deceased. This became a fashion in the tombs of the wealthy in the fifteenth century, and surviving examples still offer a stark reminder of the vanity of earthly riches. Later, Puritan tomb stones in the colonial United States frequently depicted winged skulls, skeletons, or angels snuffing out candles. These are among the numerous themes associated with skull imagery.

Another example of memento mori is provided by the chapels of bones, such as the Capela dos Ossos in Évora or the Capuchin Crypt in Rome. These are chapels where the walls are totally or partially covered by human remains, mostly bones. The entrance to the Capela dos Ossos has the following sentence: "We bones, lying here bare, await yours."

Visual art[edit]

Timepieces have been used to illustrate that the time of the living on Earth grows shorter with each passing minute. Public clocks would be decorated with mottos such as ultima forsan ("perhaps the last" [hour]) or vulnerant omnes, ultima necat ("they all wound, and the last kills"). Clocks have carried the motto tempus fugit, "time flees". Old striking clocks often sported automata who would appear and strike the hour; some of the celebrated automaton clocks from Augsburg, Germany, had Death striking the hour. Private people carried smaller reminders of their own mortality. Mary, Queen of Scots owned a large watch carved in the form of a silver skull, embellished with the lines of Horace, "Pale death knocks with the same tempo upon the huts of the poor and the towers of Kings."

In the late 16th and through the 17th century, memento mori jewelry was popular. Items included mourning rings,[16] pendants, lockets, and brooches.[17] These pieces depicted tiny motifs of skulls, bones, and coffins, in addition to messages and names of the departed, picked out in precious metals and enamel.[17][18]

During the same period there emerged the artistic genre known as vanitas, Latin for "emptiness" or "vanity". Especially popular in Holland and then spreading to other European nations, vanitas paintings typically represented assemblages of numerous symbolic objects such as human skulls, guttering candles, wilting flowers, soap bubbles, butterflies, and hourglasses. In combination, vanitas assemblies conveyed the impermanence of human endeavours and of the decay that is inevitable with the passage of time. See also the themes associated with the image of the skull.

Literature[edit]

Memento mori is also an important literary theme. Well-known literary meditations on death in English prose include Sir Thomas Browne's Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial and Jeremy Taylor's Holy Living and Holy Dying. These works were part of a Jacobean cult of melancholia that marked the end of the Elizabethan era. In the late eighteenth century, literary elegies were a common genre; Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard and Edward Young's Night Thoughts are typical members of the genre.

In the European devotional literature of the Renaissance, the Ars Moriendi, memento mori had moral value by reminding individuals of their mortality.[19]

Music[edit]

Apart from the genre of requiem and funeral music, there is also a rich tradition of memento mori in the Early Music of Europe. Especially those facing the ever-present death during the recurring bubonic plague pandemics from the 1340s onward tried to toughen themselves by anticipating the inevitable in chants, from the simple Geisslerlieder of the Flagellant movement to the more refined cloistral or courtly songs. The lyrics often looked at life as a necessary and god-given vale of tears with death as a ransom, and they reminded people to lead sinless lives to stand a chance at Judgment Day. The following two Latin stanzas (with their English translations) are typical of memento mori in medieval music; they are from the virelai Ad Mortem Festinamus of the Llibre Vermell de Montserrat from 1399:

Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur, | Life is short, and shortly it will end; |

Danse macabre[edit]

The danse macabre is another well-known example of the memento mori theme, with its dancing depiction of the Grim Reaper carrying off rich and poor alike. This and similar depictions of Death decorated many European churches.

Gallery[edit]

The salutation of the Hermits of St. Paul of France[edit]

Memento mori was the salutation used by the Hermits of St. Paul of France (1620–1633), also known as the Brothers of Death.[20] It is sometimes claimed that the Trappists use this salutation, but this is not true.[21]

In Puritan America[edit]

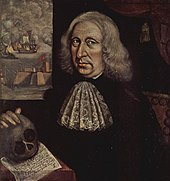

Colonial American art saw a large number of memento mori images due to Puritan influence. The Puritan community in 17th-century North America looked down upon art because they believed that it drew the faithful away from God and, if away from God, then it could only lead to the devil. However, portraits were considered historical records and, as such, they were allowed. Thomas Smith, a 17th-century Puritan, fought in many naval battles and also painted. In his self-portrait, we see these pursuits represented alongside a typical Puritan memento mori with a skull, suggesting his awareness of imminent death.

The poem underneath the skull emphasizes Thomas Smith's acceptance of death and of turning away from the world of the living:

Mexico's Day of the Dead[edit]

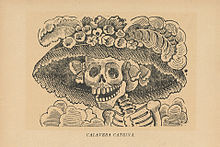

Much memento mori art is associated with the Mexican festival Day of the Dead, including skull-shaped candies and bread loaves adorned with bread "bones".

This theme was also famously expressed in the works of the Mexican engraver José Guadalupe Posada, in which people from various walks of life are depicted as skeletons.

Another manifestation of memento mori is found in the Mexican "Calavera", a literary composition in verse form normally written in honour of a person who is still alive, but written as if that person were dead. These compositions have a comedic tone and are often offered from one friend to another during Day of the Dead.[22]

Contemporary culture[edit]

Roman Krznaric suggests Memento Mori is an important topic to bring back into our thoughts and belief system; "Philosophers have come up with lots of what I call 'death tasters' – thought experiments for seizing the day."

These thought experiments are powerful to get us re-oriented back to death into current awareness and living with spontaneity. Albert Camus stated "Come to terms with death, thereafter anything is possible." Jean-Paul Sartre expressed that life is given to us early, and is shortened at the end, all the while taken away at every step of the way, emphasizing that the end is only the beginning every day.[23]

Similar concepts across cultures[edit]

In Buddhism[edit]

The Buddhist practice maraṇasati meditates on death. The word is a Pāli compound of maraṇa 'death' (an Indo-European cognate of Latin mori) and sati 'awareness', so very close to memento mori. It is first used in early Buddhist texts, the suttapiṭaka of the Pāli Canon, with parallels in the āgamas of the "Northern" Schools.

In Japanese Zen and samurai culture[edit]

In Japan, the influence of Zen Buddhist contemplation of death on indigenous culture can be gauged by the following quotation from the classic treatise on samurai ethics, Hagakure:[24]

In the annual appreciation of cherry blossom and fall colors, hanami and momijigari, it was philosophized that things are most splendid at the moment before their fall, and to aim to live and die in a similar fashion.[citation needed]

In Tibetan Buddhism[edit]

In Tibetan Buddhism, there is a mind training practice known as Lojong. The initial stages of the classic Lojong begin with 'The Four Thoughts that Turn the Mind', or, more literally, 'Four Contemplations to Cause a Revolution in the Mind'.[citation needed] The second of these four is the contemplation on impermanence and death. In particular, one contemplates that;

- All compounded things are impermanent.

- The human body is a compounded thing.

- Therefore, death of the body is certain.

- The time of death is uncertain and beyond our control.

There are a number of classic verse formulations of these contemplations meant for daily reflection to overcome our strong habitual tendency to live as though we will certainly not die today.

Lalitavistara Sutra[edit]

The following is from the Lalitavistara Sūtra, a major work in the classical Sanskrit canon:

अध्रुवं त्रिभवं शरदभ्रनिभं नटरङ्गसमा जगिर् ऊर्मिच्युती। गिरिनद्यसमं लघुशीघ्रजवं व्रजतायु जगे यथ विद्यु नभे॥ | The three worlds are fleeting like autumn clouds. |

[edit]

A very well known verse in the Pali, Sanskrit and Tibetan canons states [this is from the Sanskrit version, the Udānavarga:

सर्वे क्षयान्ता निचयाः पतनान्ताः समुच्छ्रयाः | | All that is acquired will be lost |

Shantideva, Bodhicaryavatara[edit]

Shantideva, in the Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra 'Bodhisattva's Way of Life' reflects at length:

कृताकृतापरीक्षोऽयं मृत्युर्विश्रम्भघातकः। | Death does not differentiate between tasks done and undone. |

In more modern Tibetan Buddhist works[edit]

In a practice text written by the 19th century Tibetan master Dudjom Lingpa for serious meditators, he formulates the second contemplation in this way:[28][29]

The contemporary Tibetan master, Yangthang Rinpoche, in his short text 'Summary of the View, Meditation, and Conduct':[30]

།ཁྱེད་རྙེད་དཀའ་བ་མི་ཡི་ལུས་རྟེན་རྙེད། །སྐྱེ་དཀའ་བའི་ངེས་འབྱུང་གི་བསམ་པ་སྐྱེས། །མཇལ་དཀའ་བའི་མཚན་ལྡན་གྱི་བླ་མ་མཇལ། །འཕྲད་དཀའ་བ་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་དང་འཕྲད། | You have obtained a human life, which is difficult to find, |

The Tibetan Canon also includes copious materials on the meditative preparation for the death process and intermediate period bardo between death and rebirth. Amongst them are the famous "Tibetan Book of the Dead", in Tibetan Bardo Thodol, the "Natural Liberation through Hearing in the Bardo".

In Islam[edit]

The "remembrance of death" (Arabic: تذكرة الموت, Tadhkirat al-Mawt; deriving from تذكرة, tadhkirah, Arabic for memorandum or admonition), has been a major topic of Islamic spirituality since the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in Medina. It is grounded in the Qur'an, where there are recurring injunctions to pay heed to the fate of previous generations.[31] The hadith literature, which preserves the teachings of Muhammad, records advice for believers to "remember often death, the destroyer of pleasures."[32] Some Sufis have been called "ahl al-qubur," the "people of the graves," because of their practice of frequenting graveyards to ponder on mortality and the vanity of life, based on the teaching of Muhammad to visit graves.[33] Al-Ghazali devotes to this topic the last book of his "The Revival of the Religious Sciences".[34]

Iceland[edit]

The Hávamál ("Sayings of the High One"), a 13th-century Icelandic compilation poetically attributed to the god Odin, includes two sections – the Gestaþáttr and the Loddfáfnismál – offering many gnomic proverbs expressing the memento mori philosophy, most famously Gestaþáttr number 77:

Deyr fé, | Animals die, |

See also[edit]

- Gerascophobia (fear of aging)

- Gerontophobia (fear of elderly people)

- Carpe diem

- Et in Arcadia ego

- Mono no aware

- Mortality salience

- Sic transit gloria mundi

- Tempus fugit

- Terror management theory

- Ubi sunt

- Vanitas

- YOLO (aphorism)

References[edit]

- ^ Campbell, Lorne. Van der Weyden. London: Chaucer Press, 2004. 89. ISBN 1904449247

- ^ a b Literally 'remember (that you have) to die', Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, June 2001.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, ss.vv.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, s.v.

- ^ Diogenes Laertius Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Book IX, Chapter 7, Section 38

- ^ Phaedo, 64a4.

- ^ See his Moral Letters to Lucilius.

- ^ Discourses of Epictetus, 3.24.

- ^ Henry Albert Fischel, Rabbinic Literature and Greco-Roman Philosophy: A Study of Epicurea and Rhetorica in Early Midrashic Writings, E. J. Brill, 1973, p. 95.

- ^ Marcus Aurelius, Meditations IV. 48.2.

- ^ Beard, Mary: The Roman Triumph, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, England, 2007. (hardcover), pp. 85–92.

- ^ "Final Farewell: The Culture of Death and the Afterlife". Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri. Archived from the original on 6 June 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Mary Beard, The Roman Triumph, Harvard University Press, 2009, ISBN 0674032187, pp. 85–92

- ^ Christian Dogmatics, Volume 2 (Carl E. Braaten, Robert W. Jenson), page 583

- ^ See Jeremy Taylor, Holy Living and Holy Dying.

- ^ Taylor, Gerald; Scarisbrick, Diana (1978). Finger Rings From Ancient Egypt to the Present Day. Ashmolean Museum. p. 76. ISBN 0900090545.

- ^ a b "Memento Mori". Antique Jewelry University. Lang Antiques. n.d. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Bond, Charlotte (5 December 2018). "Somber "Memento Mori" Jewelry Commissioned to Help People Mourn". The Vintage News. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Michael John Brennan, ed., The A–Z of Death and Dying: Social, Medical, and Cultural Aspects, ISBN 1440803447, s.v. "Memento Mori", p. 307f and s.v. "Ars Moriendi", p. 44

- ^ F. McGahan, "Paulists", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, s.v. Paulists

- ^ E. Obrecht, "Trappists", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, s.v. Trappists

- ^ Stanley Brandes. "Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Beyond". Chapter 5: The Poetics of Death. John Wiley & Sons, 2009

- ^ Macdonald, Fiona. "What it really means to 'Seize the day'". BBC. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ "Hagakure: Book of the Samurai". www.themathesontrust.org. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "A Buddhist Guide to Death, Dying and Suffering". www.urbandharma.org. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "84000 Reading Room | The Play in Full". 84000 Translating The Words of The Budda.

- ^ Udānavarga, 1:22.

- ^ "Foolish Dharma of an Idiot Clothed in Mud and Feathers, in 'Dujdom Lingpa's Visions of the Great Perfection, Volume 1', B. Alan Wallace (translator), Wisdom Publications".

An oral commentary by the translator is available on YouTube - ^ "Natural Liberation | Wisdom Publications". Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ The English text is available here. Archived 2018-05-14 at the Wayback Machine The Tibetan text is available here. Oral Commentary by a student of Rinpoche, B. Alan Wallace, is available here.

- ^ For instance, sura "Yasin", 36:31, "Have they not seen how many generations We destroyed before them, which indeed returned not unto them?".

- ^ "Riyad as-Salihin 579 – The Book of Miscellany – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Sunan Abi Dawud 3235 – Funerals (Kitab Al-Jana'iz) – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Al-Ghazali on Death and the Afterlife, tr. by T.J. Winter. Cambridge, Islamic Texts Society, 1989.