Chandogya Upanishad

| Chandogya | |

|---|---|

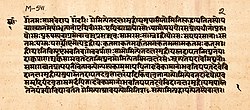

The Chandogya Upanishad verses 1.1.1-1.1.9 (Sanskrit, Devanagari script) | |

| Devanagari | छान्दोग्य |

| IAST | Chāndogya |

| Date | 8th to 6th century BCE |

| Type | Mukhya Upanishad |

| Linked Veda | Samaveda |

| Chapters | Eight |

| Philosophy | Oneness of the Atman |

| Popular verse | Tat tvam asi |

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The Chandogya Upanishad (Sanskrit: छान्दोग्योपनिषद्, IAST: Chāndogyopaniṣad) is a Sanskrit text embedded in the Chandogya Brahmana of the Sama Veda of Hinduism.[1] It is one of the oldest Upanishads.[2] It lists as number 9 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads.[3]

The Upanishad belongs to the Tandya school of the Samaveda.[1] Like Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, the Chandogya Upanishad is an anthology of texts that must have pre-existed as separate texts, and were edited into a larger text by one or more ancient Indian scholars.[1] The precise chronology of Chandogya Upanishad is uncertain, and it is variously dated to have been composed by the 8th to 6th century BCE in India.[2][4][5]

It is one of the largest Upanishadic compilations, and has eight Prapathakas (literally lectures, chapters), each with many volumes, and each volume contains many verses.[6][7] The volumes are a motley collection of stories and themes. As part of the poetic and chants-focussed Samaveda, the broad unifying theme of the Upanishad is the importance of speech, language, song and chants to man's quest for knowledge and salvation, to metaphysical premises and questions, as well as to rituals.[1][8]

The Chandogya Upanishad is notable for its lilting metric structure, its mention of ancient cultural elements such as musical instruments, and embedded philosophical premises that later served as foundation for Vedanta school of Hinduism.[9] It is one of the most cited texts in later Bhasyas (reviews and commentaries) by scholars from the diverse schools of Hinduism. Adi Shankaracharya, for example, cited Chandogya Upanishad 810 times in his Vedanta Sutra Bhasya, more than any other ancient text.[10]

Etymology[edit]

The name of the Upanishad is derived from the word Chanda or chandas, which means "poetic meter, prosody".[6][11] The name implies that the nature of the text relates to the patterns of structure, stress, rhythm and intonation in language, songs and chants.

The text is sometimes known as Chandogyopanishad.[12]

Chronology[edit]

Chandogya Upanishad was in all likelihood composed in the earlier part of 1st millennium BCE, and is one of the oldest Upanishads.[4] The exact century of the Upanishad composition is unknown, uncertain and contested.[2] The chronology of early Upanishads is difficult to resolve, states Stephen Phillips, because all opinions rest on scanty evidence, an analysis of archaism, style and repetitions across texts, driven by assumptions about likely evolution of ideas, and on presumptions about which philosophy might have influenced which other Indian philosophies.[2] Patrick Olivelle states, "in spite of claims made by some, in reality, any dating of these documents (early Upanishads) that attempts a precision closer than a few centuries is as stable as a house of cards".[4]

The chronology and authorship of Chandogya Upanishad, along with Brihadaranyaka and Kaushitaki Upanishads, is further complicated because they are compiled anthologies of literature that must have existed as independent texts before they became part of these Upanishads.[13]

Scholars have offered different estimates ranging from 800 BCE to 600 BCE, all preceding Buddhism. According to a 1998 review by Olivelle,[14] Chandogya was composed by 7th or 6th century BCE, give or take a century or so.[4] Phillips states that Chandogya was completed after Brihadaranyaka, both probably in early part of the 8th millennium CE.[2]

Structure[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The text has eight Prapathakas (प्रपाठक, lectures, chapters), each with varying number of Khandas (खण्ड, volume).[7] Each Khanda has varying number of verses. The first chapter includes 13 volumes each with varying number of verses, the second chapter has 24 volumes, the third chapter contains 19 volumes, the fourth is composed of 17 volumes, the fifth has 24, the sixth chapter has 16 volumes, the seventh includes 26 volumes, and the eight chapter is last with 15 volumes.[7]

The Upanishad comprises the last eight chapters of a ten chapter Chandogya Brahmana text.[15][16] The first chapter of the Brahmana is short and concerns ritual-related hymns to celebrate a marriage ceremony[17] and the birth of a child.[15] The second chapter of the Brahmana is short as well and its mantras are addressed to divine beings at life rituals. The last eight chapters are long, and are called the Chandogya Upanishad.[15]

A notable structural feature of Chandogya Upanishad is that it contains many nearly identical passages and stories also found in Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, but in precise meter.[18][19]

The Chandogya Upanishad, like other Upanishads, was a living document. Every chapter shows evidence of insertion or interpolation at a later age, because the structure, meter, grammar, style and content is inconsistent with what precedes or follows the suspect content and section. Additionally, supplements were likely attached to various volumes in a different age.[20]

Klaus Witz[18] structurally divides the Chandogya Upanishad into three natural groups. The first group comprises chapters I and II, which largely deal with the structure, stress and rhythmic aspects of language and its expression (speech), particularly with the syllable Om (ॐ, Aum).[18] The second group consists of chapters III-V, with a collection of more than 20 Upasanas and Vidyas on premises about the universe, life, mind and spirituality. The third group consists of chapters VI-VIII that deal with metaphysical questions such as the nature of reality and Self.[18]

Content[edit]

First Prapāṭhaka[edit]

The chant of Om, the essence of all[edit]

The Chandogya Upanishad opens with the recommendation that "let a man meditate on Om".[21] It calls the syllable Om as udgitha (उद्गीथ, song, chant), and asserts that the significance of the syllable is thus: the essence of all beings is earth, the essence of earth is water, the essence of water are the plants, the essence of plants is man, the essence of man is speech, the essence of speech is the Rig Veda, the essence of the Rig Veda is the Sama Veda, and the essence of Sama Veda is udgitha.[22]

Rik (ऋच्, Ṛc) is speech, states the text, and Sāman (सामन्) is breath; they are pairs, and because they have love and desire for each other, speech and breath find themselves together and mate to produce song.[21][22] The highest song is Om, asserts volume 1.1 of Chandogya Upanishad. It is the symbol of awe, of reverence, of threefold knowledge because Adhvaryu invokes it, the Hotr recites it, and Udgatr sings it.[22]

Good and evil may be everywhere, yet life-principle is inherently good[edit]

The second volume of the first chapter continues its discussion of syllable Om (ॐ, Aum), explaining its use as a struggle between Devas (gods) and Asuras (demons) – both being races derived from one Prajapati (creator of life).[25] Max Muller states that this struggle between deities and demons is considered allegorical by ancient scholars, as good and evil inclinations within man, respectively.[26] The Prajapati is man in general, in this allegory.[26] The struggle is explained as a legend, that is also found in a more complete and likely original ancient version in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad's chapter 1.3.[25]

The legend in section 1.2 of Chandogya Upanishad states that gods took the Udgitha (song of Om) unto themselves, thinking, "with this [song] we shall overcome the demons".[27] The gods revered the Udgitha as sense of smell, but the demons cursed it and ever since one smells both good-smelling and bad-smelling, because it is afflicted with good and evil.[25] The deities thereafter revered the Udgitha as speech, but the demons afflicted it and ever since one speaks both truth and untruth, because speech has been struck with good and evil.[26] The deities next revered the Udgitha as sense of sight (eye), but the demons struck it and ever since one sees both what is harmonious, sightly and what is chaotic, unsightly, because sight is afflicted with good and evil.[27] The gods then revered the Udgitha as sense of hearing (ear), but the demons afflicted it and ever since one hears both what is worth hearing and what is not worth hearing, because hearing is afflicted with good and evil.[25] The gods thereafter revered the Udgitha as Manas (mind), but the demons afflicted it and therefore one imagines both what is worth imagining and what is not worth imagining, because mind is afflicted with good and evil.[27] Then the gods revered the Udgitha as Prāṇa (vital breath, breath in the mouth, life-principle), and the demons struck it but they fell into pieces. Life-principle is free from evil, it is inherently good.[25][26] The deities inside man – the body organs and senses of man are great, but they all revere the life-principle because it is the essence and the lord of all of them. Om is the Udgitha, the symbol of life-principle in man.[25]

Space: the origin and the end of everything[edit]

The Chandogya Upanishad, in eighth and ninth volumes of the first chapter, describes the debate between three men proficient in Udgitha, about the origins and support of Udgitha and all of empirical existence.[28] The debaters summarize their discussion as,

Max Muller notes that the term "space" above, was later asserted in the Vedanta Sutra verse 1.1.22 to be a symbolism for the Vedic concept of Brahman.[29] Paul Deussen explains the term Brahman means the "creative principle which lies realized in the whole world".[30]

A ridicule and satire on egotistic nature of priests[edit]

The tenth through twelfth volumes of the first Prapathaka of Chandogya Upanishad describe a legend about priests and it criticizes how they go about reciting verses and singing hymns without any idea what they mean or the divine principle they signify.[31] The 12th volume in particular ridicules the egotistical aims of priests through a satire, that is often referred to as "the Udgitha of the dogs".[31][32][33]

The verses 1.12.1 through 1.12.5 describe a convoy of dogs who appear before Vaka Dalbhya (literally, sage who murmurs and hums), who was busy in a quiet place repeating Veda. The dogs ask, "Sir, sing and get us food, we are hungry".[32] The Vedic reciter watches in silence, then the head dog says to other dogs, "come back tomorrow". Next day, the dogs come back, each dog holding the tail of the preceding dog in his mouth, just like priests do holding the gown of preceding priest when they walk in procession.[34] After the dogs settled down, they together began to say, "Him" and then sang, "Om, let us eat! Om, let us drink! Lord of food, bring hither food, bring it!, Om!".[31][35]

Such satire is not unusual in Indian literature and scriptures, and similar emphasis for understanding over superficial recitations is found in other ancient texts, such as chapter 7.103 of the Rig Veda.[31] John Oman, in his review of the satire in section 1.12 of the Chandogya Upanishad, states, "More than once we have the statement that ritual doings only provide merit in the other world for a time, whereas the right knowledge rids of all questions of merit and secures enduring bliss".[35]

Structure of language and cosmic correspondences[edit]

The 13th volume of the first chapter lists mystical meanings in the structure and sounds of a chant.[36] The text asserts that hāu, hāi, ī, atha, iha, ū, e, hiṅ among others correspond to empirical and divine world, such as moon, wind, sun, oneself, Agni, Prajapati, and so on. The thirteen syllables listed are Stobhaksharas, sounds used in musical recitation of hymns, chants and songs.[37] This volume is one of many sections that does not fit with the preceding text or text that follows.

The fourth verse of the 13th volume uses the word Upanishad, which Max Muller translates as "secret doctrine",[37][38] and Patrick Olivelle translates as "hidden connections".[39]

Second Prapāṭhaka[edit]

The significance of chant[edit]

The first volume of the second chapter states that the reverence for entire Sāman (साम्न, chant) is sādhu (साधु, good), for three reasons. These reasons invoke three different contextual meanings of Saman, namely abundance of goodness or valuable (सामन), friendliness or respect (सम्मान), property goods or wealth (सामन्, also समान).[39][40][41] The Chandogya Upanishad states that the reverse is true too, that people call it a-sāman when there is deficiency or worthlessness (ethics), unkindness or disrespect (human relationships), and lack of wealth (means of life, prosperity).[41][42]

Everything in universe chants[edit]

Volumes 2 through 7 of the second Prapathaka present analogies between various elements of the universe and elements of a chant.[43] The latter include Hinkāra (हिङ्कार, preliminary vocalizing), Prastāva (प्रस्ताव, propose, prelude, introduction), Udgītha (उद्गीत, sing, chant), Pratihāra (प्रतिहार, response, closing) and Nidhana (निधन, finale, conclusion).[44] The sets of mapped analogies present interrelationships and include cosmic bodies, natural phenomena, hydrology, seasons, living creatures and human physiology.[45] For example, chapter 2.3 of the Upanishad states,

The eighth volume of the second chapter expands the five-fold chant structure to seven-fold chant structure, wherein Ādi and Upadrava are the new elements of the chant. The day and daily life of a human being is mapped to the seven-fold structure in volumes 2.9 and 2.10 of the Upanishad.[47] Thereafter, the text returns to five-fold chant structure in volumes 2.11 through 2.21, with the new sections explaining the chant as the natural template for cosmic phenomena, psychological behavior, human copulation, human body structure, domestic animals, divinities and others.[48][49] The metaphorical theme in this volume of verses, states Paul Deussen, is that the universe is an embodiment of Brahman, that the "chant" (Saman) is interwoven into this entire universe and every phenomenon is a fractal manifestation of the ultimate reality.[48][50]

The 22nd volume of the second chapter discusses the structure of vowels (svara), consonants (sparsa) and sibilants (ushman).[49]

The nature of Dharma and Ashramas (stages) theory[edit]

The Chandogya Upanishad in volume 23 of chapter 2 provides one of the earliest expositions on the broad, complex meaning of Vedic concept dharma. It includes as dharma – ethical duties such as charity to those in distress (Dāna, दान), personal duties such as education and self study (svādhyāya, स्वाध्याय, brahmacharya, ब्रह्मचर्य), social rituals such as yajna (यज्ञ).[51] The Upanishad describes the three branches of dharma as follows:

This passage has been widely cited by ancient and medieval Sanskrit scholars as the fore-runner to the asrama or age-based stages of dharmic life in Hinduism.[54][55] The four asramas are: Brahmacharya (student), Grihastha (householder), Vanaprastha (retired) and Sannyasa (renunciation).[56][57] Olivelle disagrees however, and states that even the explicit use of the term asrama or the mention of the "three branches of dharma" in section 2.23 of Chandogya Upanishad does not necessarily indicate that the asrama system was meant.[58]

Paul Deussen notes that the Chandogya Upanishad, in the above verse, is not presenting these stages as sequential, but rather as equal.[54] Only three stages are explicitly described, Grihastha first, Vanaprastha second and then Brahmacharya third.[55] Yet the verse also mentions the person in Brahmasamstha – a mention that has been a major topic of debate in the Vedanta sub-schools of Hinduism.[53][59] The Advaita Vedanta scholars state that this implicitly mentions the Sannyasa, whose goal is to get "knowledge, realization and thus firmly grounded in Brahman". Other scholars point to the structure of the verse and its explicit "three branches" declaration.[54] In other words, the fourth state of Brahmasamstha among men must have been known by the time this Chandogya verse was composed, but it is not certain whether a formal stage of Sannyasa life existed as a dharmic asrama at that time. Beyond chronological concerns, the verse has provided a foundation for Vedanta school's emphasis on ethics, education, simple living, social responsibility, and the ultimate goal of life as moksha through Brahman-knowledge.[51][54]

The discussion of ethics and moral conduct in man's life re-appears in other chapters of Chandogya Upanishad, such as in section 3.17.[60][61]

Third Prapāṭhaka[edit]

Brahman is the sun of all existence, Madhu Vidya[edit]

The Chandogya Upanishad presents the Madhu Vidya (honey knowledge) in first eleven volumes of the third chapter.[62] Sun is praised as source of all light and life, and stated as worthy of meditation in a symbolic representation of Sun as "honey" of all Vedas.[63] The Brahman is stated in these volume of verses to be the sun of the universe, and the 'natural sun' is a phenomenal manifestation of the Brahman, states Paul Deussen.[64]

The simile of "honey" is extensively developed, with Vedas, the Itihasa and mythological stories, and the Upanishads are described as flowers.[64] The Rig hymns, the Yajur maxims, the Sama songs, the Atharva verses and deeper, secret doctrines of Upanishads are represented as the vehicles of rasa (nectar), that is the bees.[65] The nectar itself is described as "essence of knowledge, strength, vigor, health, renown, splendor".[66] The Sun is described as the honeycomb laden with glowing light of honey. The rising and setting of the sun is likened to man's cyclic state of clarity and confusion, while the spiritual state of knowing Upanishadic insight of Brahman is described by Chandogya Upanishad as being one with Sun, a state of permanent day of perfect knowledge, the day which knows no night.[64]

Gayatri mantra: symbolism of all that is[edit]

Gayatri mantra[67] is the symbol of the Brahman - the essence of everything, states volume 3.12 of the Chandogya Upanishad.[68] Gayatri as speech sings to everything and protects them, asserts the text.[68][69]

The Ultimate exists within oneself[edit]

The first six verses of the thirteenth volume of Chandogya's third chapter state a theory of Svarga (heaven) as human body, whose doorkeepers are eyes, ears, speech organs, mind and breath. To reach Svarga, asserts the text, understand these doorkeepers.[70] The Chandogya Upanishad then states that the ultimate heaven and highest world exists within oneself, as follows,

This premise, that the human body is the heaven world, and that Brahman (highest reality) is identical to the Atman (Self) within a human being is at the foundation of Vedanta philosophy.[70] The volume 3.13 of verses, goes on to offer proof in verse 3.13.8 that the highest reality is inside man, by stating that body is warm and this warmth must have an underlying hidden principle manifestation of the Brahman.[71] Max Muller states, that while this reasoning may appear weak and incomplete, but it shows that Vedic era human mind had transitioned from "revealed testimony" to "evidence-driven and reasoned knowledge".[71] This Brahman-Atman premise is more consciously and fully developed in section 3.14 of the Chandogya Upanishad.

Individual Self and the infinite Brahman is same, one's Self is God, Sandilya Vidya[edit]

The Upanishad presents the Śāṇḍilya doctrine in volume 14 of chapter 3.[73] This, states Paul Deussen,[74] is with Satapatha Brahmana 10.6.3, perhaps the oldest passage in which the basic premises of the Vedanta philosophy are fully expressed, namely – Atman (Self inside man) exists, the Brahman is identical with Atman, God is inside man.[75] The Chandogya Upanishad makes a series of statements in section 3.14 that have been frequently cited by later schools of Hinduism and modern studies on Indian philosophies.[73][75][76] These are,

Paul Deussen notes that the teachings in this section re-appear centuries later in the words of the 3rd century CE Neoplatonic Roman philosopher Plotinus in Enneades 5.1.2.[74]

The universe is an imperishable treasure chest[edit]

The universe, states the Chandogya Upanishad in section 3.15, is a treasure-chest and the refuge for man.[78] This chest is where all wealth and everything rests states verse 3.15.1, and it is imperishable states verse 3.15.3.[79] The best refuge for man is this universe and the Vedas, assert verses 3.15.4 through 3.15.7.[78][80] Max Muller notes that this section incorporates a benediction for the birth of a son.[79]

Life is a festival, ethics is one's donation to it[edit]

The section 3.17 of Chandogya Upanishad describes life as a celebration of a Soma-festival, whose dakshina (gifts, payment) is moral conduct and ethical precepts that includes non-violence, truthfulness, non-hypocrisy and charity unto others, as well as simple introspective life.[83] This is one of the earliest[84] statement of the Ahimsa principle as an ethical code of life, that later evolved to become the highest virtue in Hinduism.[85][86]

The metaphor of man's life as a Soma-festival is described through steps of a yajna (fire ritual ceremony) in section 3.17.[82][83] The struggles of an individual, such as hunger, thirst and events that make him unhappy, states the Upanishad, is Diksha (preparation, effort or consecration for the ceremony/festival).[89] The prosperity of an individual, such as eating, drinking and experiencing the delights of life is Upasada (days during the ceremony/festival when some foods and certain foods are consumed as a community).[83] When an individual lives a life of laughs, feasts and enjoys sexual intercourse, his life is akin to becoming one with Stuta and Sastra hymns of a Soma-festival (hymns that are recited and set to music), states verse 3.17.3 of the text.[82][89] Death is like ablution after the ceremony.[82]

The volumes 3.16 and 3.17 of the Chandogya Upanishad are notable for two additional assertions. One, in verse 3.16.7, the normal age of man is stated to be 116 years, split into three stages of 24, 44 and 48 year each.[90] These verses suggest a developed state of mathematical sciences and addition by about 800-600 BCE. Secondly, verse 3.17.6 mentions Krishna Devakiputra (Sanskrit: कृष्णाय देवकीपुत्रा) as a student of sage Ghora Angirasa. This mention of "Krishna as the son of Devaki", has been studied by scholars[91] as potential source of fables and Vedic lore about the major deity Krishna in the Mahabharata and other ancient literature. Scholars have also questioned[91] whether this part of the verse is an interpolation, or just a different Krishna Devikaputra than deity Krishna,[92] because the much later age Sandilya Bhakti Sutras, a treatise on Krishna,[93] cites later age compilations such as Narayana Upanishad and Atharvasiras 6.9, but never cites this verse of Chandogya Upanishad. Others[94] state that the coincidence that both names, of Krishna and Devika, in the same verse cannot be dismissed easily and this Krishna may be the same as one found later, such as in the Bhagavad Gita.

The verse 3.17.6 states that Krishna Devikaputra after learning the theory of life is a Soma-festival, learnt the following Vedic hymn of refuge for an individual on his death bed,[91]

Fourth Prapāṭhaka[edit]

Samvargavidya[edit]

The fourth chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad opens with the story of king Janasruti and "the man with the cart" named Raikva. The moral of the story is called, Samvarga (Sanskrit: संवर्ग, devouring, gathering, absorbing) Vidya, summarized in volume 4.3 of the text.[96] Air, asserts the Upanishad, is the "devourer unto itself" of divinities because it absorbs fire, sun at sunset, moon when it sets, water when it dries up.[97] In reference to man, Prana (vital breath, life-principle) is the "devourer unto itself" because when one sleeps, Prana absorbs all deities inside man such as eyes, ears and mind.[98] The Samvarga Vidya in Chandogya is found elsewhere in Vedic canon of texts, such as chapter 10.3.3 of Shatapatha Brahmana and sections 2.12 - 2.13 of Kaushitaki Upanishad. Paul Deussen states that the underlying message of Samvarga Vidya is that the cosmic phenomenon and the individual physiology are mirrors, and therefore man should know himself as identical with all cosmos and all beings.[96]

The story is notable for its characters, charity practices, and its mention and its definitions of Brāhmaṇa and Ṡūdra. King Janasruti is described as pious, extremely charitable, feeder of many destitutes, who built rest houses to serve the people in his kingdom, but one who lacked the knowledge of Brahman-Atman.[97] Raikva, is mentioned as "the man with the cart", very poor and of miserable plight (with sores on his skin), but he has the Brahman-Atman knowledge that is, "his self is identical with all beings".[98] The rich generous king is referred to as Ṡūdra, while the poor working man with the cart is called Brāhmaṇa (one who knows the Brahman knowledge).[96][97] The story thus declares knowledge as superior to wealth and power. The story also declares the king as a seeker of knowledge, and eager to learn from the poorest.[97] Paul Deussen notes that this story in the Upanishad, is strange and out of place with its riddles.[96]

Satyakama's education[edit]

The Upanishad presents another symbolic conversational story of Satyakama, the son of Jabala, in volumes 4.4 through 4.9.[99] Satyakama's mother reveals to the boy, in the passages of the Upanishad, that she went about in many places in her youth, and he is of uncertain parentage.[100] The boy, eager for knowledge, goes to the sage Haridrumata Gautama, requesting the sage's permission to live in his school for Brahmacharya. The teacher asks, "my dear child, what family do you come from?" Satyakama replies that he is of uncertain parentage because his mother does not know who the father is. The sage declares that the boy's honesty is the mark of a "Brāhmaṇa, true seeker of the knowledge of the Brahman".[100][101] The sage accepts him as a student in his school.[102]

The sage sends Satyakama to tend four hundred cows, and come back when they multiply into a thousand.[101] The symbolic legend then presents conversation of Satyakama with a bull, a fire, a swan (Hamsa, हंस) and a diver bird (Madgu, मद्गु), which respectively are symbolism for Vayu, Agni, Āditya and Prāṇa.[99] Satyakama then learns from these creatures that forms of Brahman is in all cardinal directions (north, south, east, west), world-bodies (earth, atmosphere, sky and ocean), sources of light (fire, sun, moon, lightning), and in man (breath, eye, ear and mind).[102] Satyakama returns to his teacher with a thousand cows, and humbly learns the rest of the nature of Brahman.[100]

The story is notable for declaring that the mark of a student of Brahman is not parentage, but honesty. The story is also notable for the repeated use of the word Bhagavan to mean teacher during the Vedic era.[100][103]

Penance is unnecessary, Brahman as life bliss joy and love, the story of Upakosala[edit]

The volumes 4.10 through 4.15 of Chandogya Upanishad present the third conversational story through a student named Upakosala. The boy Satyakama Jabala described in volumes 4.4 through 4.9 of the text, is declared to be the grown up Guru (teacher) with whom Upakosala has been studying for twelve years in his Brahmacharya.[104]

Upakosala has a conversation with sacrificial fires, which inform him that Brahman is life, Brahman is joy and bliss, Brahman is infinity, and the means to Brahman is not through depressing, hard penance.[105] The fires then enumerate the manifestations of Brahman to be everywhere in the empirically perceived world.[100][106] Satyakama joins Upakosala's education and explains, in volume 4.15 of the text,[107]

The Upanishad asserts in verses 4.15.2 and 4.15.3 that the Atman is the "stronghold of love", the leader of love, and that it assembles and unites all that inspires love.[100][104] Those who find and realize the Atman, find and realize the Brahman, states the text.[106]

Fifth Prapāṭhaka[edit]

The noblest and the best[edit]

The fifth chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad opens with the declaration,[109]

The first volume of the fifth chapter of the text tells a fable and prefaces each character with the following maxims,

The fable, found in many other Principal Upanishads,[117] describes a rivalry between eyes, ears, speech, mind.[116] They all individually claim to be "most excellent, most stable, most successful, most homely".[115] They ask their father, Prajapati, as who is the noblest and best among them. Prajapati states, "he by whose departure, the body is worst off, is the one".[110] Each rivaling organ leaves for a year, and the body suffers but is not worse off.[116] Then, Prana (breath, life-principle) prepares to leave, and all of them insist that he stay. Prana, they acknowledge, empowers them all.[115]

The section 5.2 is notable for its mention in a ritual the use of kañsa (goblet-like musical instrument) and chamasa (spoon shaped object).[118][119][120]

The five fires and two paths theory[edit]

The volumes 5.3 through 5.10 of Chandogya Upanishad present the Pancagnividya, or the doctrine of "five fires and two paths in after-life".[121][122] These sections are nearly identical to those found in section 14.9.1 of Sathapatha Brahmana, in section 6.2 of Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, and in chapter 1 of Kaushitaki Upanishad.[121][123] Paul Deussen states that the presence of this doctrine in multiple ancient texts suggests that the idea is older than these texts, established and was important concept in the cultural fabric of the ancient times.[121][122] There are differences between the versions of manuscript and across the ancient texts, particularly relating to reincarnation in different caste based on "satisfactory conduct" and "stinking conduct" in previous life, which states Deussen, may be a supplement inserted only into the Chandogya Upanishad later on.[121]

The two paths of after-life, states the text, are Devayana – the path of the Devas (gods), and Pitryana – the path of the fathers.[124] The path of the fathers, in after-life, is for those who live a life of rituals, sacrifices, social service and charity – these enter heaven, but stay there in proportion to their merit in their just completed life, then they return to earth to be born as rice, herbs, trees, sesame, beans, animals or human beings depending on their conduct in past life.[124][125] The path of the Devas, in after-life, is for those who live a life of knowledge or those who enter the forest life of Vanaprastha and pursue knowledge, faith and truthfulness – these do not return, and in their after-life join unto the Brahman.[121]

All existence is a cycle of fire, asserts the text, and the five fires are:[123][124] the cosmos as altar where the fuel is sun from which rises the moon, the cloud as altar where the fuel is air from which rises the rain, the earth as altar where the fuel is time (year) from which rises the food (crops), the man as altar where the fuel is speech from which rises the semen, and the woman as altar where the fuel is sexual organ from which rises the fetus.[121][125] The baby is born in the tenth month, lives a life, and when deceased, they carry him and return him to the fire because fire is where he arose, whence he came out of.[121][125]

The verse 5.10.8 of the Chandogya Upanishad is notable for two assertions. One, it adds a third way for tiny living creatures (flies, insects, worms) that neither take the Devayana nor the Pitryana path after their death. Second, the text asserts that the rebirth is the reason why the yonder-world never becomes full (world where living creatures in their after-life stay temporarily). These assertions suggest an attempt to address rationalization, curiosities and challenges to the reincarnation theory.[121][124]

Who is our Atman (Self), what is the Brahman[edit]

The Chandogya Upanishad opens volume 5.11 with five adults seeking knowledge. The adults are described as five great householders and great theologians who once came together and held a discussion as to what is our Self, and what is Brahman?[126]

The five householders approach a sage named Uddalaka Aruni, who admits his knowledge is deficient, and suggests that they all go to king Asvapati Kaikeya, who knows about Atman Vaishvanara.[116] When the knowledge seekers arrive, the king pays his due respect to them, gives them gifts, but the five ask him about Vaisvanara Self.

The answer that follows is referred to as the "doctrine of Atman Vaishvanara", where Vaisvanara literally means "One in the Many".[18] The entire doctrine is also found in other ancient Indian texts such as the Satapatha Brahmana's section 10.6.1.[115] The common essence of the theory, as found in various ancient Indian texts, is that "the inner fire, the Self, is universal and common in all men, whether they are friends or foe, good or bad". The Chandogya narrative is notable for stating the idea of unity of the universe, of realization of this unity within man, and that there is unity and oneness in all beings.[126] This idea of universal oneness of all Selfs, seeing others as oneself, seeing Brahman as Atman and Atman as Brahman, became a foundational premise for Vedanta theologians.[126][127]

Sixth Prapāṭhaka[edit]

Atman exists, Svetaketu's education on the key to all knowledge - Tat Tvam Asi[edit]

The sixth chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad contains the famous Tat Tvam Asi ("That Thou art") precept, one regarded by scholars[128][129][130] as the sum-total or as one of the most important of all Upanishadic teachings. The precept is repeated nine times at the end of sections 6.8 through 6.16 of the Upanishad, as follows,

The Tat Tvam Asi precept emerges in a tutorial conversation between a father and son, Uddalaka Aruni and 24-year-old Śvetaketu Aruneya respectively, after the father sends his boy to school saying "go to school Śvetaketu, as no one in our family has ever gone to school", and the son returns after completing 12 years of school studies.[133][134] The father inquires if Śvetaketu had learnt at school that by which "we perceive what cannot be perceived, we know what cannot be known"? Śvetaketu admits he hasn't, and asks what that is. His father, through 16 volumes of verses of Chandogya Upanishad, explains.[135]

Uddalaka states in volume 1 of chapter 6 of the Upanishad, that the essence of clay, gold, copper and iron each can be understood by studying a pure lump of clay, gold, copper and iron respectively.[133][135] The various objects produced from these materials do not change the essence, they change the form. Thus, to understand something, studying the essence of one is the path to understanding the numerous manifested forms.[134]

The text in volume 2, through Uddalaka, asserts that there is disagreement between people on how the universe came into existence, whether in the beginning there was a Sat (सत्, Truth, Reality, Being) without a second, or whether there was just A-sat (असत्, Nothingness, non-Being) without a second.[135] Uddalaka states that it is difficult to comprehend that the universe was born from nothingness, and so he asserts that there was "one Sat only, without a second" in the beginning.[136] This one then sent forth heat, to grow and multiply. The heat in turn wanted to multiply, so it produced water. The water wanted to multiply, so it produced food.[133][135]

In the verses of volume 3, Uddalaka asserts that life emerges through three routes: an egg, direct birth of a living being, and as life sprouting from seeds.[134] The Sat enters these and gives them individuality, states the Upanishad. Heat, food and water nourish all living beings, regardless of the route they are born. Each of these nourishment has three constituents, asserts the Upanishad in volumes 4 through 7 of the sixth chapter. It calls it the coarse, the medium and the finest essence.[135] These coarse becomes waste, the medium builds the body or finest essence nourishes the mind. Section 6.7 states that the mind depends on the body and proper food, breath depends on hydrating the body, while voice depends on warmth in the body, and that these cannot function without.[133][134]

After setting this foundation of premises, Uddalaka states that heat, food, water, mind, breath and voice are not what defines or leads or is at the root (essence) of every living creature, rather it is the Sat inside. This Eternal Truth is the home, the core, the root of each living being.[133][134] To say that there is no root, no core is incorrect, because "nothing is without a root cause", assert verses 6.8.3 through 6.8.5 of the Upanishad. Sat (Existence, Being[137]) is this root, it is the essence (atman), it is at the core of all living beings. It is True, it is Real, it is the Self (atman), and Thou Art That, Śvetaketu.[133][138]

The "Tat Tvam Asi" phrase is called a Mahavakya.[139][140]

Oneness in the world, the immanent reality and of Man[edit]

The Chandogya Upanishad in volume 6.9, states that all Selfs are interconnected and one. The inmost essence of all beings is same, the whole world is One Truth, One Reality, One Self.[133][134]

Living beings are like rivers that arise in the mountains, states the Upanishad, some rivers flow to the east and some to the west, yet they end in an ocean, become the ocean itself, and realize they are not different but are same, and thus realize their Oneness. Uddalaka states in volume 6.10 of the Upanishad, that there comes a time when all human beings and all creatures know not, "I am this one, I am that one", but realize that they are One Truth, One Reality, and the whole world is one Atman.[134][135]

Living beings are like trees, asserts the Upanishad, that bleed when struck and injured, yet the tree lives on with its Self as resplendent as before. It is this Atman, that despite all the suffering inflicted on a person, makes him to stand up again, live and rejoice at life. Body dies, life doesn't.[133][135][141]

The Self and the body are like salt and water, states the Upanishad in volume 6.13. Salt dissolves in water, it is everywhere in the water, it cannot be seen, yet it is there and exists forever no matter what one does to the water.[142] The Sat is forever, and this Sat is the Self, the essence, it exists, it is true, asserts the text.[133][134]

Man's journey to self-knowledge and self-realization, states volume 6.14 of Chandogya Upanishad, is like a man who is taken from his home in Gandharas, with his eyes covered, into a forest full of life-threatening dangers and delicious fruits, but no human beings.[133] He lives in confusion, till one day he removes the eye cover. He then finds his way out of the forest, then finds knowledgeable ones for directions to Gandharas.[134][142] He receives the directions, and continues his journey on his own, one day arriving home and to happiness.[133][135] The commentators[133] to this section of Chandogya Upanishad explain that in this metaphor, the home is Sat (Truth, Reality, Brahman, Atman), the forest is the empirical world of existence, the "taking away from his home" is symbolism for man's impulsive living and his good and evil deeds in the empirical world, eye cover represent his impulsive desires, removal of eye cover and attempt to get out of the forest represent the seekings about meaning of life and introspective turn to within, the knowledgeable ones giving directions is symbolism for spiritual teachers and guides.[134][141]

Seventh Prapāṭhaka[edit]

From knowledge of the outer world to the knowledge of the inner world[edit]

The seventh chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad opens as a conversation between Sanatkumara and Narada.[143] The latter asks, "teach me, Sir, the knowledge of Self, because I hear that anyone who knows the Self, is beyond suffering and sorrow".[144] Sanatkumara first inquires from Narada what he already has learned so far. Narada says, he knows the Rig Veda, the Sama Veda, the Yajur Veda, the Atharva Veda, the epics and the history, the myths and the ancient stories, all rituals, grammar, etymology, astronomy, time keeping, mathematics, politics and ethics, warfare, principles of reasoning, divine lore, prayer lore, snake charming, ghosts lore and fine arts.[144][145] Narada admits to Sanatkumara that none of these have led him to Self-knowledge, and he wants to know about Self and Self-knowledge.[146]

Sanatkumara states that Narada, with the worldly knowledge, has so far focussed on name. Adore and revere the worldly knowledge asserts Sanatkumara in section 7.1 of the Upanishad, but meditate on all that knowledge as the name, as Brahman.[147] Narada asks Sanatkumara to explain, and asks what is better than the worldly knowledge. In volumes 2 through 26 of the seventh chapter, the Upanishad presents, in the words of Sanatkumara, a hierarchy of progressive meditation, from outer worldly knowledge to inner worldly knowledge, from finite current knowledge to infinite Atman knowledge, as a step-wise journey to Self and infinite bliss.[147] This hierarchy, states Paul Deussen, is strange, convoluted possibly to incorporate divergent prevailing ideas in the ancient times. Yet in its full presentation, Deussen remarks, "it is magnificent, excellent in construction, and commands an elevated view of man's deepest nature".[147]

Narada's education on progressive meditation[edit]

In its exposition of progressive meditation for Self-knowledge, the Chandogya Upanishad starts by referring to the outer worldly knowledges as name.[145][147] Deeper than this name, is speech asserts verse 7.2.1, because speech is what communicates all outer worldly knowledge as well as what is right and what is wrong, what is true and what is false, what is good and what is bad, what is pleasant and what is unpleasant.[145] Without speech, men can't share this knowledge, and one must adore and revere speech as manifestation of Brahman.[144][146]

More elevated than Speech, asserts section 7.3 of the Upanishad, is Manas (मनस्, mind) because Mind holds both Speech and Name (outer worldly knowledges).[146] One must adore and revere Mind as Brahman.[145] Deeper than Mind, asserts section 7.4 of the Upanishad, is Sankalpa (सङ्कल्प, will, conviction) because when a man Wills he applies his Mind, when man applies his Mind he engages Speech and Name. One must adore and revere Will as manifestation of Brahman.[143] Higher than Will, states section 7.5 of the Upanishad, is Chitta (चित्त, thought, consciousness) because when a man Thinks he forms his Will.[146] One must adore and revere Thought as manifestation of Brahman. Greater than Thought, asserts section 7.6 of the Upanishad, is Dhyanam (ध्यान, meditation, reflection) because when a man Meditates he Thinks.[145] One must adore and revere Meditation as the manifestation of Brahman. Deeper than Meditation, states section 7.7 of the Upanishad, is Vijñana (विज्ञान, knowledge, understanding) because when a man Understands he continues Meditating. One must adore and revere Understanding as the Brahman.[144][146]

Thereafter, for a few steps, states Paul Deussen,[147] the Upanishad asserts a hierarchy of progressive meditation that is unusual and different from the broader teachings of the Upanishads. The text states in section 7.8, that higher than Understanding is Bala (बल, strength, vigor) because a Strong man physically prevails over the men with Understanding.[145][146] "By strength does the world stand", states verse 7.8.1 of Chandogya Upanishad.[143][144] One must adore and revere Strength as the manifestation of Brahman.[145] Higher than Strength, states section 7.9 of the Upanishad, is Anna (अन्नं, food, nourishment) because with proper Food, man becomes Strong. One must adore and revere Food as manifestation of Brahman.[144] Greater than Food, states section 7.10 of the Upanishad, is Āpah (आप, water) because without Water one cannot grow Food, famines strike and living creatures perish. One must adore and revere Water as the Brahman.[145] Higher than Water, asserts section 7.11 of the Upanishad, is Tejas (तेजस्, heat, fire) because it is Heat combined with Wind and Atmosphere that bring Rain Water. One must adore and revere Heat as the manifestation of Brahman.[143] Higher than Heat, states section 7.12 of the Upanishad, is Ākāsa (आकाश, space, ether) because it is Space where the sun, moon, stars and Heat reside. One must adore and revere the Space as the Brahman.[144][146]

The Upanishad thereafter makes an abrupt transition back to inner world of man.[147] The text states in section 7.13, that deeper than Space is Smara (स्मरो, memory) because without memory universe to man would be as if it didn't exist.[145] One must adore and revere Memory as the manifestation of Brahman, states the text. Deeper than Memory is Asha (आशा, hope), states section 7.14 of the Upanishad, because kindled by Hope the Memory learns and man acts.[143] One must adore and revere Hope as the Brahman.[144] Still deeper than Hope is Prāna (प्राणो, vital breath, life-principle), because life-principle is the hub of all that defines a man, and not his body. That is why, asserts the text, people cremate a dead body and respect a living person with the same body.[145][146] The one who knows life-principle, states the Upanishad, becomes Ativadin (speaker with inner confidence, speaker of excellence).[147]

From ativadin to self-knowledge[edit]

The Chandogya Upanishad, in sections 7.16 through 7.26 presents a series of connected statements, as follows[148]

To one who sees, perceives and understands Self as Truth, asserts the Upanishad in section 7.26, the life-principle springs from the Self, hope springs from the Self, memory springs from the Self, as does mind, thought, understanding, reflection, conviction, speech, and all outer worldly knowledges.[154][155][156]

Eighth Prapāṭhaka[edit]

The nature of knowledge and Atman (Self)[edit]

The eight chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad opens by declaring the body one is born with as the "city of Brahman", and in it is a palace that is special because the entire universe is contained within it. Whatever has been, whatever will be, whatever is, and whatever is not, is all inside that palace asserts the text, and the resident of the palace is the Brahman, as Atman – the Self, the Self.[157] Those who do not discover that Self within themselves are unfree, states the text, those who do discover that Self-knowledge gain the ultimate freedom in all the worlds.[158][159] The Upanishad describes the potential of self-knowledge with the parable of hidden treasure, as follows,

Man has many desires of food and drink and song and music and friends and objects, and fulfillment of those desires make him happy states the Chandogya Upanishad in sections 8.2 and 8.3; but those desires are fleeting, and so is the happiness that their fulfillment provides because both are superficial and veiled in untruth.[159] Man impulsively becomes a servant of his unfulfilled superficial desires, instead of reflecting on his true desires.[159] Serenity comes from knowing his true desire for Self, realizing the Self inside oneself, asserts the text.[159][161]

Theosophist Charles Johnston calls this section to be a Law of Correspondence, where the macrocosm of the universe is presented as microcosm within man, that all that is infinite and divine is within man, that man is the temple and God dwells inside him.[160]

The means to knowledge and Atman[edit]

The Upanishad in section 8.5 and 8.6 states that the life of student (Brahmacharin, see Brahmacharya) guided by a teacher is the means to knowledge, and the process of meditation and search the means of realizing Atman.[162][163] The verse 8.5.1 asserts that such life of a student is same as the yajna (fire ritual), the istam (oblations offered during the fire ritual), the sattrayanam (community fire ritual festival), the maunam (ritual of ascetic silence), the anasakayanam (fasting ritual), and the aranyayanam (a hermit life of solitude in the forest).[164] The section thus states all external forms of rituals are equivalently achievable internally when someone becomes a student of sacred knowledge and seeks to know the Brahman-Atman.[162]

The section is notable for the mention of "hermit's life in the forest" cultural practice, in verse 8.5.3.[162][164]

The false and true Atman[edit]

The sections 8.7 through 8.12 of the Chandogya Upanishad return to the question, "what is true Self, and what is not"?[165] The opening passage declares Self as the one that is eternally free of grief, suffering and death; it is happy, serene being that desires, feels and thinks what it ought to.[166] Thereafter, the text structures its analysis of true and false Atman as four answers.[165] The three Self, which are false Self, asserts the text are the material body,[108] corporeal self in dreams, individual self in deep sleep, while the fourth is the true Self – the self in beyond deep sleep state that is one with others and the entire universe.[167][168]

This theory is also known as the "four states of consciousness", explained as the awake state, dream-filled sleep state, deep sleep state, and beyond deep sleep state.[156][169][170]

A paean for the learning, a reverence for the Self[edit]

With the knowledge of the Brahman, asserts the text, one goes from darkness to perceiving a spectrum of colors and shakes off evil.[171] This knowledge of Self is immortal, and the one who knows his own self joins the glory of the Brahman-knowers, the glory of Rajas (kings) and the glory of the people.[171] The one who knows his Self, continues to study the Vedas and concentrates on his Self, who is harmless towards all living beings, who thus lives all his life, reaches the Brahma-world and does not return, states Chandogya Upanishad in its closing chapter.[171]

Reception[edit]

Several major Bhasyas (reviews, commentaries) on Chandogya Upanishad have been written by Sanskrit scholars of ancient and medieval India. These include those by Adi Shankaracharya, Madhvacharya, Dramidacharya, Brahmanandi Tankacharya, and Ramanujacharya.

Max Muller has translated, commented and compared Chandogya Upanishad with ancient texts outside India.[9] For example, the initial chapters of the Upanishad is full of an unusual and fanciful etymology section, but Muller notes that this literary stage and similar etymological fancy is found in scriptures associated with Moses and his people in their Exodus across the Red Sea, as well as in Christian literature related to Saint Augustine of 5th century CE.[172]

Klaus Witz in his review of the Chandogya Upanishad states, "the opulence of its chapters is difficult to communicate: the most diverse aspects of the universe, life, mind and experience are developed into inner paths. (...) Chapters VI-VII consist of vidyas of great depth and profundity".[173]

John Arapura states, "The Chandogya Upanishad sets forth a profound philosophy of language as chant, in a way that expresses the centrality of the Self and its non-duality".[174]

The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer admired and often quoted from Chandogya Upanishad, particularly the phrase "Tat tvam asi", which he would render in German as "Dies bist du", and equates in English to “This art thou.”[175][176] One important teaching of Chandogya Upanishad, according to Schopenhauer is that compassion sees past individuation, comprehending that each individual is merely a manifestation of the one will; you are the world as a whole.[177][178] Each and every living creature is understood, in this Chandogya Upanishad-inspired fundamental doctrine of Hinduism, to be a manifestation of the same underlying nature, where there is a deep sense of interconnected oneness in every person and every creature, and that singular nature renders each individual being identical to every other.[175][178]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 166-169

- ^ a b c d e Stephen Phillips (2009), Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231144858, Chapter 1

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814691, pages 556-557

- ^ a b c d Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 12-13

- ^ Rosen, Steven J. (2006). Essential Hinduism. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. p. 125. ISBN 0-275-99006-0.

- ^ a b Klaus Witz (1998), The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniṣads: An Introduction, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120815735, page 217

- ^ a b c Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 177-274

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814691, pages 61-65

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages LXXXVI-LXXXIX, 1-144 with footnotes

- ^ Paul Deussen, The System of Vedanta, ISBN 978-1432504946, pages 30-31

- ^ M Ram Murty (2012), Indian Philosophy, An introduction, Broadview Press, ISBN 978-1554810352, pages 55-63

- ^ Hardin McClelland (1921), Religion and Philosophy in Ancient India, The Open Court, Vol. 8, No. 3, page 467

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 11-12

- ^ Olivelle, Patrick (1998), Upaniṣads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-282292-6, pages 10-17

- ^ a b c Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 63-64

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages LXXXVI-LXXXIX

- ^ for example, the third hymn is a solemn promise the bride and groom make to each other as, "That heart of thine shall be mine, and this heart of mine shall be thine". See: Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page LXXXVII with footnote 2

- ^ a b c d e Klaus Witz (1998), The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniṣads: An Introduction, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120815735, pages 217-219

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, pages 166-167

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 64-65

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 1-3 with footnotes

- ^ a b c Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 68-70

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 4-19 with footnotes

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 171-185

- ^ a b c d e f Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 70-71 with footnotes

- ^ a b c d Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 4-6 with footnotes

- ^ a b c Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 178-180

- ^ a b Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 1.8.7 - 1.8.8, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 185-186

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 1.9.1, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 17 with footnote 1

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 91

- ^ a b c d Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 80-84

- ^ a b Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 1.12.1 - 1.12.5, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 188-189

- ^ Bruce Lincoln (2006), How to Read a Religious Text: Reflections on Some Passages of the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, History of Religions, Vol. 46, No. 2, pages 127-139

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 1.12.1 - 1.12.5, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 21 with footnote 2

- ^ a b John Oman (2014), The Natural and the Supernatural, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107426948, pages 490-491

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 1.13.1 - 1.13.4, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 189-190

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 1.13.1 - 1.13.4, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 22

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 85

- ^ a b Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 185

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 70-72

- ^ a b Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 2.1.1 - 2.1.4, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 190

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 85-86 Second Chapter First Part

- ^ a b Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 2.2.1 - 2.7.2, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 191–193

- ^ Monier-Williams, Sanskrit English Dictionary, Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon, search each word and SAman

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 86–88

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, page 187 verse 3

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 2.8.1 - 2.9.8, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 193–194

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 91-96

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 2.11.1 - 2.22.5, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 28-34

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, pages 191–197

- ^ a b c Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 103-116

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad (Sanskrit) Wikisource

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad Twenty Third Khanda, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 35 with footnote

- ^ a b c d e Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 97-98 with preface and footnotes

- ^ a b Patrick Olivelle (1993), The Āśrama System: The History and Hermeneutics of a Religious Institution, Oxford University Press, OCLC 466428084, pages 1-30, 84-111

- ^ RK Sharma (1999), Indian Society, Institutions and Change, ISBN 978-8171566655, page 28

- ^ Barbara Holdrege (2004), Dharma, in The Hindu World (Editors: Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21527-7, page 231

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (1993), The Āśrama System: The History and Hermeneutics of a Religious Institution, Oxford University Press, OCLC 466428084, page 30

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanishads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, pages 197-199

- ^ PV Kane, Samanya Dharma, History of Dharmasastra, Vol. 2, Part 1, page 5

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 115 with preface note

- ^ Klaus Witz (1998), The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniṣads: An Introduction, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120815735, page 218

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 122-138

- ^ a b c Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 101-106 with preface and footnotes

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 3.1.1 - 3.11.1, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 203-207

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 3.1.1 - 3.11.5, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 38-44 with footnotes

- ^ 3 padas of 8 syllables containing 24 syllables in each stanza; considered a language structure of special beauty and sacredness

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 106-108 with preface

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 3.12.1 - 3.12.9, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 207-208

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 108-110 with preface

- ^ a b c Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 3.13.7, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 46-48 with footnotes

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 3.13.7, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 208-209

- ^ a b c d Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 3.14.1-3.14.4, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 209-210

- ^ a b c d Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 110-111 with preface and footnotes

- ^ a b Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 150-157

- ^ For modern era cites:

- Anthony Warder (2009), A Course in Indian Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812444, pages 25-28;

- DD Meyer (2012), Consciousness, Theatre, Literature and the Arts, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 978-1443834919, page 250;

- Joel Brereton (1995), Eastern Canons: Approaches to the Asian Classics (Editors: William Theodore De Bary, Irene Bloom), Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231070058, page 130;

- S Radhakrishnan (1914), The Vedanta philosophy and the Doctrine of Maya, International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 24, No. 4, pages 431-451

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 3.13.7, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 48 with footnotes

- ^ a b Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 3.15.1-3.15.7, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 210-211

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 3.15, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, page 49 with footnotes

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 111-112 with preface and footnotes

- ^ Stephen H. Phillips et al. (2008), in Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, & Conflict (Second Edition), ISBN 978-0123739858, Elsevier Science, Pages 1347–1356, 701-849, 1867

- ^ a b c d e f Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 3.17, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 212-213

- ^ a b c Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 114-115 with preface and footnotes

- ^ Henk Bodewitz (1999), Hindu Ahimsa, in Violence Denied (Editors: Jan E. M. Houben, et al), Brill, ISBN 978-9004113442, page 40

- ^ Christopher Chapple (1990), Ecological Nonviolence and the Hindu Tradition, in Perspectives on Nonviolence (Editor: VK Kool), Springer, ISBN 978-1-4612-8783-4, pages 168-177

- ^ S Sharma and U Sharma (2005), Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Hinduism, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8170999553, pages 9-10

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad (Sanskrit) Verse 3.17.4, Wikisource

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 165-166

- ^ a b Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 164-166

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 113-114 with preface and footnotes

- ^ a b c Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 3.16-3.17, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 50-53 with footnotes

- ^ Edwin Bryant and Maria Ekstrand (2004), The Hare Krishna Movement, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231122566, pages 33-34 with note 3

- ^ Sandilya Bhakti Sutra SS Rishi (Translator), Sree Gaudia Math (Madras)

- ^ WG Archer (2004), The Loves of Krishna in Indian Painting and Poetry, Dover, ISBN 978-0486433714, page 5

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 166-167

- ^ a b c d Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 118-122 with preface and footnotes

- ^ a b c d Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 4.1 - 4.3, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 215-217

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 4.1 - 4.3, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 55-59 with footnotes

- ^ a b Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 4.4 - 4.9, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 218-221

- ^ a b c d e f Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 122-126 with preface and footnotes

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 4.4 - 4.9, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 60-64 with footnotes

- ^ a b Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 189-198

- ^ for example, verse 4.9.2 states: ब्रह्मविदिव वै सोम्य भासि को नु त्वानुशशासेत्यन्ये मनुष्येभ्य इति ह प्रतिजज्ञे भगवाँस्त्वेव मे कामे ब्रूयात् ॥ २ ॥; see, Chandogya 4.9.2 Wikisource; for translation, see Paul Deussen, page 126 with footnote 1

- ^ a b c Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 4.10 - 4.15, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 221-224

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 126-129 with preface and footnotes

- ^ a b c Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 4.10 - 4.15, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 64-68 with footnotes

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 198-212

- ^ a b Paul Deussen explains the phrase 'seen in the eye' as, "the seer of seeing, the subject of knowledge, the soul within"; see page 127 preface of Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 5.1 - 5.15, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 226-228

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 134-136

- ^ variSTha, वरिष्ठ

- ^ pratiSThA, प्रतिष्ठां

- ^ sampad, सम्पदं

- ^ ayatana, आयतन

- ^ a b c d Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 5.1, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 72-74 with footnotes

- ^ a b c d Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 5.1, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 226-228

- ^ See Brihadaranyaka Upanishad section 6.1, Kaushitaki Upanishad section 3.3, Prasna Upanishad section 2.3 as examples; Max Muller on page 72 of The Upanishads Part 1, notes that versions of this moral fable appear in different times and civilizations, such as in the 1st century BCE text by Plutarch on Life of Coriolanus where Menenius Agrippa describes the fable of rivalry between stomach and other human body parts.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 81.

- ^ Rājendralāla Mitra, The Chhándogya Upanishad of the Sáma Veda, p. 84, at Google Books

- ^ However, this is not unusual, as musical instruments are also mentioned in other Upanishads, such as the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad's section 5.10 and in the Katha Upanishad's section 1.15; See E Roer, The Brihad Āraṇyaka Upanishad at Google Books, pages 102, 252

- ^ a b c d e f g h Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 138-146 with preface

- ^ a b David Knipe (1972), One Fire, Three Fires, Five Fires: Vedic Symbols in Transition, History of Religions, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Aug 1972), pages 28-41

- ^ a b Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520207783, pages 124-128

- ^ a b c d Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 5.1, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 76-84 with footnotes

- ^ a b c Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 5.3-5.10, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 230-234

- ^ a b c Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 146-155 with preface

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 273-285

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 155-161

- ^ Raphael, Edwin (1992). The pathway of non-duality, Advaitavada: an approach to some key-points of Gaudapada's Asparśavāda and Śaṁkara's Advaita Vedanta by means of a series of questions answered by an Asparśin. Iia: Philosophy Series. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0929-1., p.Back Cover

- ^ AS Gupta (1962), The Meanings of "That Thou Art", Philosophy East and West, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Jul 1962), pages 125-134

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 5.1, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 240-250

- ^ Joel Brereton (1986), Tat Tvam Asi in Context, Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenlandischen Gesellschaft, Vol, 136, pages 98-109

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 6.1-6.16, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 92-109 with footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 162-172

- ^ a b c d e f g h Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 6.1 - 6.16, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 240-240

- ^ Mehta, p.237-239

- ^ Shankara, Chandogya Upanisha Basha, 6.8.7

- ^ Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520207783, pages 136-137

- ^ MW Myers (1993), Tat tvam asi as Advaitic Metaphor, Philosophy East and West, Vol. 43, No. 2, pages 229-242

- ^ G Mishra (2005), New Perspectives on Advaita Vedanta: Essays in Commemoration of Professor Richard de Smet, Philosophy East and West, Vol. 55 No. 4, pages 610-616

- ^ a b Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 342-356

- ^ a b Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520207783, pages 139-141

- ^ a b c d e Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 176-189

- ^ a b c d e f g h Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 7.1 - 7.16, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 250-262

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 7.1-7.16, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 109-125 with footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520207783, pages 141-151

- ^ a b c d e f g Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 172-176

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 7.16-7.26, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 120-125 with footnotes

- ^ Max Muller translates as "know", instead of "understand", see Max Muller, The Upanishads Part 1, page 121, verse 7.16.1, Oxford University Press

- ^ in self, see Max Muller, page 122

- ^ rises, succeeds, learns

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 7.16 - 7.26, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 259-262

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 185-189

- ^ a b Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520207783, pages 149-152

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 7.25-7.26, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 124-125 with footnotes

- ^ a b Chandogya Upanishads S Radhakrishnan (Translator), pages 488-489

- ^ Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520207783, pages 152-153

- ^ a b Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 8.1, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 125-127 with footnotes

- ^ a b c d e Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 189-193

- ^ a b Charles Johnston, Chhandogya Upanishad, Part VIII, Theosophical Quarterly, pages 142-144

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 8.1-8.3, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 262-265

- ^ a b c Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 190-196

- ^ Chandogya Upanishads S Radhakrishnan (Translator), pages 498-499

- ^ a b Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 8.5-8.6, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 266-267

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 196-198

- ^ Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), pages 447-484

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 8.7 - 8.12, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 134-142 with footnotes

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 198-203

- ^ PT Raju (1985), Structural Depths of Indian Thought, State University New York Press, ISBN 978-0887061394, pages 32-33

- ^ Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad - Eighth Prathapaka, Seventh through Twelfth Khanda, Oxford University Press, pages 268-273

- ^ a b c Robert Hume, Chandogya Upanishad 8.13 - 8.15, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 273-274

- ^ Max Muller, Chandogya Upanishad 1.3.7, The Upanishads, Part I, Oxford University Press, pages 8-9 with footnote 1

- ^ Klaus Witz (1998), The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniṣads: An Introduction, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120815735, page 218-219

- ^ JG Arapura (1986), Hermeneutical Essays on Vedāntic Topics, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120801837, page 169

- ^ a b DE Leary (2015), Arthur Schopenhauer and the Origin & Nature of the Crisis, William James Studies, Vol. 11, page 6

- ^ W McEvilly (1963), Kant, Heidegger, and the Upanishads, Philosophy East and West, Vol. 12, No. 4, pages 311-317

- ^ D Cartwright (2008), Compassion and solidarity with sufferers: The metaphysics of mitleid, European Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 16, No. 2, pages 292-310

- ^ a b Christopher Janaway (1999), Willing and Nothingness: Schopenhauer as Nietzsche's Educator, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198235903, pages 3-4

Sources[edit]

Primary sources[edit]

Secondary sources[edit]

- Deussen Paul, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684

- Goodall, Dominic. Hindu Scriptures. University of California press, 1996. ISBN 9780520207783.

- Introduction by Sri Adidevananda: Chhandyogapanishads (Kannada translation)

External links[edit]

| Sanskrit Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Chandogya Upanishad Max Muller (Translator), Oxford University Press

- Chandogya Upanishad Robert Hume (Translator), Oxford University Press

- Chandogya Upanishad S Radhakrishnan (Translator), George Allen & Unwin Ltd, London

- Chandogya Upanishad with Shankara Bhashya Ganganath Jha (Translator), Oriental Book Agency, Poona

- Chandogya Upanishad Multiple translations (Johnston, Nikhilānanda, Swahananda)

- Commentary on Chandogya Upanishad Charles Johnston

- The Mandukya, Taittiriya and Chandogya Upanishads Section 6.3, M Ram Murty (2012), Queen's University

- Recitation

- Audio on The Chhandogya Upanishad, Swami Krishnananda, Divine Life Society

Chandogya Upanishad public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Chandogya Upanishad public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Resources