This article is about the political philosophy and movement that uphold liberty as a core principle. For the type of libertarianism stressing both individual freedom and social equality, see Left-libertarianism. For the type of libertarianism supporting capitalism and private ownership of natural resources, see Right-libertarianism. Libertarianism (from French: libertaire, "libertarian"; from Latin: libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy and movement that upholds liberty as a core principle.[1] Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, emphasizing free association, freedom of choice, individualism and voluntary association.[2] Libertarians share a skepticism of authority and state power, but some of them diverge on the scope of their opposition to existing economic and political systems. Various schools of libertarian thought offer a range of views regarding the legitimate functions of state and private power, often calling for the restriction or dissolution of coercive social institutions. Different categorizations have been used to distinguish various forms of libertarianism.[3][4] Scholars distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital, usually along left–right or socialist–capitalist lines.[5]

Libertarianism originated as a form of left-wing politics such as anti-authoritarian and anti-state socialists like anarchists,[6] especially social anarchists,[7] but more generally libertarian communists/Marxists and libertarian socialists.[8][9] These libertarians seek to abolish capitalism and private ownership of the means of production, or else to restrict their purview or effects to usufruct property norms, in favor of common or cooperative ownership and management, viewing private property as a barrier to freedom and liberty.[10][11][12][13]

Left-libertarian[14][15][16][17][18] ideologies include anarchist schools of thought, alongside many other anti-paternalist and New Left schools of thought centered around economic egalitarianism as well as geolibertarianism, green politics, market-oriented left-libertarianism and the Steiner–Vallentyne school.[14][17][19][20][21] In the mid-20th century, right-libertarian[15][18][22][23] proponents of anarcho-capitalism and minarchism co-opted[8][24] the term libertarian to advocate laissez-faire capitalism and strong private property rights such as in land, infrastructure and natural resources.[25] The latter is the dominant form of libertarianism in the United States,[23] where it advocates civil liberties,[26] natural law,[27] free-market capitalism[28][29] and a major reversal of the modern welfare state.[30]

Overview[edit]

Etymology[edit]

The first recorded use of the term libertarian was in 1789, when William Belsham wrote about libertarianism in the context of metaphysics.[31] As early as 1796, libertarian came to mean an advocate or defender of liberty, especially in the political and social spheres, when the London Packet printed on 12 February the following: "Lately marched out of the Prison at Bristol, 450 of the French Libertarians".[32] It was again used in a political sense in 1802 in a short piece critiquing a poem by "the author of Gebir" and has since been used with this meaning.[33][34][35]

The use of the term libertarian to describe a new set of political positions has been traced to the French cognate libertaire, coined in a letter French libertarian communist Joseph Déjacque wrote to mutualist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1857.[36][37][38] Déjacque also used the term for his anarchist publication Le Libertaire, Journal du mouvement social (Libertarian: Journal of Social Movement) which was printed from 9 June 1858 to 4 February 1861 in New York City.[39][40] Sébastien Faure, another French libertarian communist, began publishing a new Le Libertaire in the mid-1890s while France's Third Republic enacted the so-called villainous laws (lois scélérates) which banned anarchist publications in France. Libertarianism has frequently been used to refer to anarchism and libertarian socialism since this time.[41][42][43]

In the United States, libertarian was popularized by the individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker around the late 1870s and early 1880s.[44] Libertarianism as a synonym for liberalism was popularized in May 1955 by writer Dean Russell, a colleague of Leonard Read and a classical liberal himself. Russell justified the choice of the term as follows:

Many of us call ourselves "liberals." And it is true that the word "liberal" once described persons who respected the individual and feared the use of mass compulsions. But the leftists have now corrupted that once-proud term to identify themselves and their program of more government ownership of property and more controls over persons. As a result, those of us who believe in freedom must explain that when we call ourselves liberals, we mean liberals in the uncorrupted classical sense. At best, this is awkward and subject to misunderstanding. Here is a suggestion: Let those of us who love liberty trade-mark and reserve for our own use the good and honorable word "libertarian."[45][46][47]

Subsequently, a growing number of Americans with classical liberal beliefs began to describe themselves as libertarians. One person responsible for popularizing the term libertarian in this sense was Murray Rothbard, who started publishing libertarian works in the 1960s.[48] Rothbard described this modern use of the words overtly as a "capture" from his enemies, writing that "for the first time in my memory, we, 'our side,' had captured a crucial word from the enemy. 'Libertarians' had long been simply a polite word for left-wing anarchists, that is for anti-private property anarchists, either of the communist or syndicalist variety. But now we had taken it over".[24][8]

In the 1970s, Robert Nozick was responsible for popularizing this usage of the term in academic and philosophical circles outside the United States,[23][49][50] especially with the publication of Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974), a response to social liberal John Rawls's A Theory of Justice (1971).[51] In the book, Nozick proposed a minimal state on the grounds that it was an inevitable phenomenon which could arise without violating individual rights.[52]

According to common meanings of conservative and liberal, libertarianism in the United States has been described as conservative on economic issues (economic liberalism and fiscal conservatism) and liberal on personal freedom (civil libertarianism and cultural liberalism).[53] It is also often associated with a foreign policy of non-interventionism.[54][55]

Definition[edit]

Although libertarianism originated as a form of left-wing politics,[21][56] the development in the mid-20th century of modern libertarianism in the United States led several authors and political scientists to use two or more categorizations[3][4] to distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital, usually along left–right or socialist–capitalist lines,[5] Unlike right-libertarians, who reject the label due to its association with conservatism and right-wing politics, calling themselves simply libertarians, proponents of free-market anti-capitalism in the United States consciously label themselves as left-libertarians and see themselves as being part of a broad libertarian left.[21][56]

While the term libertarian has been largely synonymous with anarchism as part of the left,[9][57] continuing today as part of the libertarian left in opposition to the moderate left such as social democracy or authoritarian and statist socialism, its meaning has more recently diluted with wider adoption from ideologically disparate groups,[9] including the right.[15][22] As a term, libertarian can include both the New Left Marxists (who do not associate with a vanguard party) and extreme liberals (primarily concerned with civil liberties) or civil libertarians. Additionally, some libertarians use the term libertarian socialist to avoid anarchism's negative connotations and emphasize its connections with socialism.[9][58]

The revival of free-market ideologies during the mid- to late 20th century came with disagreement over what to call the movement. While many of its adherents prefer the term libertarian, many conservative libertarians reject the term's association with the 1960s New Left and its connotations of libertine hedonism.[59] The movement is divided over the use of conservatism as an alternative.[60] Those who seek both economic and social liberty would be known as liberals, but that term developed associations opposite of the limited government, low-taxation, minimal state advocated by the movement.[61] Name variants of the free-market revival movement include classical liberalism, economic liberalism, free-market liberalism and neoliberalism.[59] As a term, libertarian or economic libertarian has the most colloquial acceptance to describe a member of the movement, with the latter term being based on both the ideology's primacy of economics and its distinction from libertarians of the New Left.[60]

While both historical libertarianism and contemporary economic libertarianism share general antipathy towards power by government authority, the latter exempts power wielded through free-market capitalism. Historically, libertarians including Herbert Spencer and Max Stirner supported the protection of an individual's freedom from powers of government and private ownership.[62] In contrast, while condemning governmental encroachment on personal liberties, modern American libertarians support freedoms on the basis of their agreement with private property rights.[63] The abolishment of public amenities is a common theme in modern American libertarian writings.[64]

According to modern American libertarian Walter Block, left-libertarians and right-libertarians agree with certain libertarian premises, but "where [they] differ is in terms of the logical implications of these founding axioms".[65] Although several modern American libertarians reject the political spectrum, especially the left–right political spectrum,[26][66][67][68][69] several strands of libertarianism in the United States and right-libertarianism have been described as being right-wing,[70] New Right[71][72] or radical right[73][74] and reactionary.[30] While some American libertarians such as Walter Block,[65] Harry Browne,[67] Tibor Machan,[69] Justin Raimondo,[68] Leonard Read[66] and Murray Rothbard[26] deny any association with either the left or right, other American libertarians such as Kevin Carson,[21] Karl Hess,[75] Roderick T. Long[76] and Sheldon Richman[77] have written about libertarianism's left wing opposition to authoritarian rule and argued that libertarianism is fundamentally a left-wing position.[78] Rothbard himself previously made the same point.[79]

Philosophy[edit]

All libertarians begin with a conception of personal autonomy from which they argue in favor of civil liberties and a reduction or elimination of the state.[1] People described as being left-libertarian or right-libertarian generally tend to call themselves simply libertarians and refer to their philosophy as libertarianism. As a result, some political scientists and writers classify the forms of libertarianism into two or more groups[3][4] to distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital.[5][13] In the United States, proponents of free-market anti-capitalism consciously label themselves as left-libertarians and see themselves as being part of a broad libertarian left.[21][56]

Left-libertarianism[15][16][18] encompasses those libertarian beliefs that claim the Earth's natural resources belong to everyone in an egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively.[14][17][19][20][23] Contemporary left-libertarians such as Hillel Steiner, Peter Vallentyne, Philippe Van Parijs, Michael Otsuka and David Ellerman believe the appropriation of land must leave "enough and as good" for others or be taxed by society to compensate for the exclusionary effects of private property.[14][20] Socialist libertarians[10][11][12][13] such as social and individualist anarchists, libertarian Marxists, council communists, Luxemburgists and De Leonists promote usufruct and socialist economic theories, including communism, collectivism, syndicalism and mutualism.[19][21] They criticize the state for being the defender of private property and believe capitalism entails wage slavery.[10][11][12]

Right-libertarianism[15][18][22][23] developed in the United States in the mid-20th century from the works of European writers like John Locke, Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig Von Mises and is the most popular conception of libertarianism in the United States today.[23][49] Commonly referred to as a continuation or radicalization of classical liberalism,[80][81] the most important of these early right-libertarian philosophers was Robert Nozick.[23][49][52] While sharing left-libertarians' advocacy for social freedom, right-libertarians value the social institutions that enforce conditions of capitalism while rejecting institutions that function in opposition to these on the grounds that such interventions represent unnecessary coercion of individuals and abrogation of their economic freedom.[82] Anarcho-capitalists[18][22] seek the elimination of the state in favor of privately funded security services while minarchists defend night-watchman states which maintain only those functions of government necessary to safeguard natural rights, understood in terms of self-ownership or autonomy.[83]

Libertarian paternalism[84] is a position advocated in the international bestseller Nudge by two American scholars, namely the economist Richard Thaler and the jurist Cass Sunstein.[85] In the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman provides the brief summary: "Thaler and Sunstein advocate a position of libertarian paternalism, in which the state and other institutions are allowed to Nudge people to make decisions that serve their own long-term interests. The designation of joining a pension plan as the default option is an example of a nudge. It is difficult to argue that anyone's freedom is diminished by being automatically enrolled in the plan, when they merely have to check a box to opt out".[86] Nudge is considered an important piece of literature in behavioral economics.[86]

Neo-libertarianism combines "the libertarian's moral commitment to negative liberty with a procedure that selects principles for restricting liberty on the basis of a unanimous agreement in which everyone's particular interests receive a fair hearing".[87] Neo-libertarianism has its roots at least as far back as 1980, when it was first described by the American philosopher James Sterba of the University of Notre Dame. Sterba observed that libertarianism advocates for a government that does no more than protection against force, fraud, theft, enforcement of contracts and other negative liberties as contrasted with positive liberties by Isaiah Berlin.[88] Sterba contrasted this with the older libertarian ideal of a night watchman state, or minarchism. Sterba held that it is "obviously impossible for everyone in society to be guaranteed complete liberty as defined by this ideal: after all, people's actual wants as well as their conceivable wants can come into serious conflict. [...] [I]t is also impossible for everyone in society to be completely free from the interference of other persons".[89] In 2013, Sterna wrote that "I shall show that moral commitment to an ideal of 'negative' liberty, which does not lead to a night-watchman state, but instead requires sufficient government to provide each person in society with the relatively high minimum of liberty that persons using Rawls' decision procedure would select. The political program actually justified by an ideal of negative liberty I shall call Neo-Libertarianism".[90]

Typology[edit]

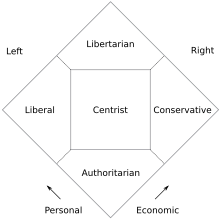

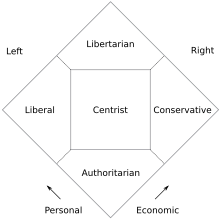

In the United States, libertarian is a typology used to describe a political position that advocates small government and is culturally liberal and fiscally conservative in a two-dimensional political spectrum such as the libertarian-inspired Nolan Chart, where the other major typologies are conservative, liberal and populist.[53][91][92][93] Libertarians support legalization of victimless crimes such as the use of marijuana while opposing high levels of taxation and government spending on health, welfare and education.[53] Libertarian was adopted in the United States, where liberal had become associated with a version that supports extensive government spending on social policies.[47] Libertarian may also refers to an anarchist ideology that developed in the 19th century and to a liberal version which developed in the United States that is avowedly pro-capitalist.[14][15][18]

According to polls, approximately one in four Americans self-identify as libertarian.[94][95][96][97] While this group is not typically ideologically driven, the term libertarian is commonly used to describe the form of libertarianism widely practiced in the United States and is the common meaning of the word libertarianism in the United States.[23] This form is often named liberalism elsewhere such as in Europe, where liberalism has a different common meaning than in the United States.[47] In some academic circles, this form is called right-libertarianism as a complement to left-libertarianism, with acceptance of capitalism or the private ownership of land as being the distinguishing feature.[14][15][18]

History[edit]

Liberalism[edit]

Although elements of libertarianism can be traced as far back as the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao-Tzu and the higher-law concepts of the Greeks and the Israelites,[98][99] it was in 17th-century England that libertarian ideas began to take modern form in the writings of the Levellers and John Locke. In the middle of that century, opponents of royal power began to be called Whigs, or sometimes simply Opposition or Country, as opposed to Court writers.[100]

During the 18th century and Age of Enlightenment, liberal ideas flourished in Europe and North America.[101][102] Libertarians of various schools were influenced by liberal ideas.[103] For philosopher Roderick T. Long, libertarians "share a common—or at least an overlapping—intellectual ancestry. [Libertarians] [...] claim the seventeenth century English Levellers and the eighteenth century French encyclopedists among their ideological forebears; and [...] usually share an admiration for Thomas Jefferson[104][105][106] and Thomas Paine".[107]

Thomas Paine, whose theory of property showed a libertarian concern with the redistribution of resources John Locke greatly influenced both libertarianism and the modern world in his writings published before and after the English Revolution of 1688, especially A Letter Concerning Toleration (1667), Two Treatises of Government (1689) and An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690). In the text of 1689, he established the basis of liberal political theory, i.e. that people's rights existed before government; that the purpose of government is to protect personal and property rights; that people may dissolve governments that do not do so; and that representative government is the best form to protect rights.[108]

The United States Declaration of Independence was inspired by Locke in its statement: "[T]o secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it".[109] Nevertheless, scholar Ellen Meiksins Wood says that "there are doctrines of individualism that are opposed to Lockean individualism [...] and non-Lockean individualism may encompass socialism".[110]

According to Murray Rothbard, the libertarian creed emerged from the liberal challenges to an "absolute central State and a king ruling by divine right on top of an older, restrictive web of feudal land monopolies and urban guild controls and restrictions" as well as the mercantilism of a bureaucratic warfaring state allied with privileged merchants. The object of liberals was individual liberty in the economy, in personal freedoms and civil liberty, separation of state and religion and peace as an alternative to imperial aggrandizement. He cites Locke's contemporaries, the Levellers, who held similar views. Also influential were the English Cato's Letters during the early 1700s, reprinted eagerly by American colonists who already were free of European aristocracy and feudal land monopolies.[109]

In January 1776, only two years after coming to America from England, Thomas Paine published his pamphlet Common Sense calling for independence for the colonies.[111] Paine promoted liberal ideas in clear and concise language that allowed the general public to understand the debates among the political elites.[112] Common Sense was immensely popular in disseminating these ideas,[113] selling hundreds of thousands of copies.[114] Paine would later write the Rights of Man and The Age of Reason and participate in the French Revolution.[111] Paine's theory of property showed a "libertarian concern" with the redistribution of resources.[115]

In 1793, William Godwin wrote a libertarian philosophical treatise titled Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness which criticized ideas of human rights and of society by contract based on vague promises. He took liberalism to its logical anarchic conclusion by rejecting all political institutions, law, government and apparatus of coercion as well as all political protest and insurrection. Instead of institutionalized justice, Godwin proposed that people influence one another to moral goodness through informal reasoned persuasion, including in the associations they joined as this would facilitate happiness.[116][117]

Anarchism[edit]

Modern anarchism sprang from the secular or religious thought of the Enlightenment, particularly Jean-Jacques Rousseau's arguments for the moral centrality of freedom.[118]

As part of the political turmoil of the 1790s in the wake of the French Revolution, William Godwin developed the first expression of modern anarchist thought.[119][120] According to Peter Kropotkin, Godwin was "the first to formulate the political and economical conceptions of anarchism, even though he did not give that name to the ideas developed in his work"[121] while Godwin attached his anarchist ideas to an early Edmund Burke.[122]

Godwin is generally regarded as the founder of the school of thought known as philosophical anarchism. He argued in Political Justice (1793)[120][123] that government has an inherently malevolent influence on society and that it perpetuates dependency and ignorance. He thought that the spread of the use of reason to the masses would eventually cause government to wither away as an unnecessary force. Although he did not accord the state with moral legitimacy, he was against the use of revolutionary tactics for removing the government from power. Rather, Godwin advocated for its replacement through a process of peaceful evolution.[120][124]

His aversion to the imposition of a rules-based society led him to denounce, as a manifestation of the people's "mental enslavement", the foundations of law, property rights and even the institution of marriage. Godwin considered the basic foundations of society as constraining the natural development of individuals to use their powers of reasoning to arrive at a mutually beneficial method of social organization. In each case, government and its institutions are shown to constrain the development of our capacity to live wholly in accordance with the full and free exercise of private judgment.[120]

In France, various anarchist currents were present during the Revolutionary period, with some revolutionaries using the term anarchiste in a positive light as early as September 1793.[125] The enragés opposed revolutionary government as a contradiction in terms. Denouncing the Jacobin dictatorship, Jean Varlet wrote in 1794 that "government and revolution are incompatible, unless the people wishes to set its constituted authorities in permanent insurrection against itself".[126] In his "Manifesto of the Equals", Sylvain Maréchal looked forward to the disappearance, once and for all, of "the revolting distinction between rich and poor, of great and small, of masters and valets, of governors and governed".[126]

Libertarian socialism[edit]

Libertarian communism, libertarian Marxism and libertarian socialism are all terms which activists with a variety of perspectives have applied to their views.[127] Anarchist communist philosopher Joseph Déjacque was the first person to describe himself as a libertarian.[128] Unlike mutualist anarchist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, he argued that "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature".[129][130] According to anarchist historian Max Nettlau, the first use of the term libertarian communism was in November 1880, when a French anarchist congress employed it to more clearly identify its doctrines.[131] The French anarchist journalist Sébastien Faure started the weekly paper Le Libertaire (The Libertarian) in 1895.[132]

Individualist anarchism represents several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual and their will over any kinds of external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems.[133][134] An influential form of individualist anarchism called egoism[135] or egoist anarchism was expounded by one of the earliest and best-known proponents of individualist anarchism, the German Max Stirner.[136] Stirner's The Ego and Its Own, published in 1844, is a founding text of the philosophy.[136] According to Stirner, the only limitation on the rights of the individual is their power to obtain what they desire,[137] without regard for God, state or morality.[138] Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw unions of egoists, non-systematic associations continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will,[139] which Stirner proposed as a form of organisation in place of the state.[140] Egoist anarchists argue that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous union between individuals.[141] Egoism has inspired many interpretations of Stirner's philosophy. Stirner's philosophy was re-discovered and promoted by German philosophical anarchist and LGBT activist John Henry Mackay. Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist,[142] and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published.[143] For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, "[i]t is apparent [...] that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. [...] William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form".[144]

Later, Benjamin Tucker fused Stirner's egoism with the economics of Warren and Proudhon in his eclectic influential publication Liberty. From these early influences, individualist anarchism in different countries attracted a small yet diverse following of bohemian artists and intellectuals,[145] free love and birth control advocates (anarchism and issues related to love and sex),[146][147] individualist naturists nudists (anarcho-naturism),[148][149][150] free thought and anti-clerical activists[151][152] as well as young anarchist outlaws in what became known as illegalism and individual reclamation[153][154] (European individualist anarchism and individualist anarchism in France). These authors and activists included Émile Armand, Han Ryner, Henri Zisly, Renzo Novatore, Miguel Gimenez Igualada, Adolf Brand and Lev Chernyi.

Sébastien Faure, prominent French theorist of libertarian communism as well as atheist and freethought militant In 1873, the follower and translator of Proudhon, the Catalan Francesc Pi i Margall, became President of Spain with a program which wanted "to establish a decentralized, or "cantonalist," political system on Proudhonian lines",[155] who according to Rudolf Rocker had "political ideas, [...] much in common with those of Richard Price, Joseph Priestly [sic], Thomas Paine, Jefferson, and other representatives of the Anglo-American liberalism of the first period. He wanted to limit the power of the state to a minimum and gradually replace it by a Socialist economic order".[156] On the other hand, Fermín Salvochea was a mayor of the city of Cádiz and a president of the province of Cádiz. He was one of the main propagators of anarchist thought in that area in the late 19th century and is considered to be "perhaps the most beloved figure in the Spanish Anarchist movement of the 19th century".[157][158] Ideologically, he was influenced by Bradlaugh, Owen and Paine, whose works he had studied during his stay in England and Kropotkin, whom he read later.[157]

The revolutionary wave of 1917–1923 saw the active participation of anarchists in Russia and Europe. Russian anarchists participated alongside the Bolsheviks in both the February and October 1917 revolutions. However, Bolsheviks in central Russia quickly began to imprison or drive underground the libertarian anarchists. Many fled to the Ukraine,[159] where they fought to defend the Free Territory in the Russian Civil War against the White movement, monarchists and other opponents of revolution and then against Bolsheviks as part of the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine led by Nestor Makhno, who established an anarchist society in the region for a number of months. Expelled American anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman protested Bolshevik policy before they left Russia.[160] The victory of the Bolsheviks damaged anarchist movements internationally as workers and activists joined Communist parties. In France and the United States, for example, members of the major syndicalist movements of the CGT and IWW joined the Communist International.[161] In Paris, the Dielo Truda group of Russian anarchist exiles which included Nestor Makhno issued a 1926 manifesto, the Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft), calling for new anarchist organizing structures.[162][163]

In Germany, the Bavarian Soviet Republic of 1918–1919 had libertarian socialist characteristics.[164][165] In Italy, the anarcho-syndicalist trade union Unione Sindacale Italiana grew to 800,000 members from 1918 to 1921 during the so-called Biennio Rosso.[166] With the rise of fascism in Europe between the 1920s and the 1930s, anarchists began to fight fascists in Italy,[167] in France during the February 1934 riots[168] and in Spain where the CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) boycott of elections led to a right-wing victory and its later participation in voting in 1936 helped bring the popular front back to power. This led to a ruling class attempted coup and the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).[169] Gruppo Comunista Anarchico di Firenze held that the during early twentieth century, the terms libertarian communism and anarchist communism became synonymous within the international anarchist movement as a result of the close connection they had in Spain (anarchism in Spain), with libertarian communism becoming the prevalent term.[170]

Murray Bookchin wrote that the Spanish libertarian movement of the mid-1930s was unique because its workers' control and collectives—which came out of a three-generation "massive libertarian movement"—divided the republican camp and challenged the Marxists. "Urban anarchists" created libertarian communist forms of organization which evolved into the CNT, a syndicalist union providing the infrastructure for a libertarian society. Also formed were local bodies to administer social and economic life on a decentralized libertarian basis. Much of the infrastructure was destroyed during the 1930s Spanish Civil War against authoritarian and fascist forces.[171]

The Iberian Federation of Libertarian Youth[172] (FIJL, Spanish: Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Libertarias), sometimes abbreviated as Libertarian Youth (Juventudes Libertarias), was a libertarian socialist[173] organization created in 1932 in Madrid.[174] At its second congress in February 1937, the FIJL organized a plenum of regional organizations. In October 1938, from the 16th through the 30th in Barcelona the FIJL participated in a national plenum of the libertarian movement, also attended by members of the CNT and the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI).[175] The FIJL exists until today. When the republican forces lost the Spanish Civil War, the city of Madrid was turned over to the Francoist forces in 1939 by the last non-Francoist mayor of the city, the anarchist Melchor Rodríguez García.[176] During autumn of 1931, the "Manifesto of the 30" was published by militants of the anarchist trade union CNT and among those who signed it there was the CNT General Secretary (1922–1923) Joan Peiro, Angel Pestaña CNT (General Secretary in 1929) and Juan Lopez Sanchez. They were called treintismo and they were calling for libertarian possibilism which advocated achieving libertarian socialist ends with participation inside structures of contemporary parliamentary democracy.[177] In 1932, they establish the Syndicalist Party which participates in the 1936 Spanish general elections and proceed to be a part of the leftist coalition of parties known as the Popular Front obtaining two congressmen (Pestaña and Benito Pabon). In 1938, Horacio Prieto, general secretary of the CNT, proposes that the Iberian Anarchist Federation transforms itself into the Libertarian Socialist Party and that it participates in the national elections.[178]

Murray Bookchin, American libertarian socialist theorist and proponent of libertarian municipalism The Manifesto of Libertarian Communism was written in 1953 by Georges Fontenis for the Federation Communiste Libertaire of France. It is one of the key texts of the anarchist-communist current known as platformism.[179] In 1968, the International of Anarchist Federations was founded during an international anarchist conference in Carrara, Italy to advance libertarian solidarity. It wanted to form "a strong and organized workers movement, agreeing with the libertarian ideas".[180][181] In the United States, the Libertarian League was founded in New York City in 1954 as a left-libertarian political organization building on the Libertarian Book Club.[182][183] Members included Sam Dolgoff,[184] Russell Blackwell, Dave Van Ronk, Enrico Arrigoni[185] and Murray Bookchin.

In Australia, the Sydney Push was a predominantly left-wing intellectual subculture in Sydney from the late 1940s to the early 1970s which became associated with the label Sydney libertarianism. Well known associates of the Push include Jim Baker, John Flaus, Harry Hooton, Margaret Fink, Sasha Soldatow,[186] Lex Banning, Eva Cox, Richard Appleton, Paddy McGuinness, David Makinson, Germaine Greer, Clive James, Robert Hughes, Frank Moorhouse and Lillian Roxon. Amongst the key intellectual figures in Push debates were philosophers David J. Ivison, George Molnar, Roelof Smilde, Darcy Waters and Jim Baker, as recorded in Baker's memoir Sydney Libertarians and the Push, published in the libertarian Broadsheet in 1975.[187] An understanding of libertarian values and social theory can be obtained from their publications, a few of which are available online.[188][189]

In 1969, French platformist anarcho-communist Daniel Guérin published an essay in 1969 called "Libertarian Marxism?" in which he dealt with the debate between Karl Marx and Mikhail Bakunin at the First International and afterwards suggested that "libertarian Marxism rejects determinism and fatalism, giving the greater place to individual will, intuition, imagination, reflex speeds, and to the deep instincts of the masses, which are more far-seeing in hours of crisis than the reasonings of the 'elites'; libertarian Marxism thinks of the effects of surprise, provocation and boldness, refuses to be cluttered and paralyzed by a heavy 'scientific' apparatus, doesn't equivocate or bluff, and guards itself from adventurism as much as from fear of the unknown".[190]

Libertarian Marxist currents often draw from Marx and Engels' later works, specifically the Grundrisse and The Civil War in France.[191] They emphasize the Marxist belief in the ability of the working class to forge its own destiny without the need for a revolutionary party or state.[192] Libertarian Marxism includes currents such an autonomism, council communism, left communism, Lettrism, New Left, Situationism, Socialisme ou Barbarie and operaismo, among others.[193]

In the United States, there existed from 1970 to 1981 the publication Root & Branch[194] which had as a subtitle A Libertarian Marxist Journal.[195] In 1974, the Libertarian Communism journal was started in the United Kingdom by a group inside the Socialist Party of Great Britain.[196] In 1986, the anarcho-syndicalist Sam Dolgoff started and led the publication Libertarian Labor Review in the United States[197] which decided to rename itself as Anarcho-Syndicalist Review in order to avoid confusion with right-libertarian views.[198]

Individualist anarchism in the United States[edit]

The indigenous anarchist tradition in the United States was largely individualist.[199] In 1825, Josiah Warren became aware of the social system of utopian socialist Robert Owen and began to talk with others in Cincinnati about founding a communist colony.[200] When this group failed to come to an agreement about the form and goals of their proposed community, Warren "sold his factory after only two years of operation, packed up his young family, and took his place as one of 900 or so Owenites who had decided to become part of the founding population of New Harmony, Indiana".[201] Warren termed the phrase "cost the limit of price"[202] and "proposed a system to pay people with certificates indicating how many hours of work they did. They could exchange the notes at local time stores for goods that took the same amount of time to produce".[203] He put his theories to the test by establishing an experimental labor-for-labor store called the Cincinnati Time Store where trade was facilitated by labor notes. The store proved successful and operated for three years, after which it was closed so that Warren could pursue establishing colonies based on mutualism, including Utopia and Modern Times. After New Harmony failed, Warren shifted his "ideological loyalties" from socialism to anarchism "which was no great leap, given that Owen's socialism had been predicated on Godwin's anarchism".[204] Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist[203] and the four-page weekly paper The Peaceful Revolutionist he edited during 1833 was the first anarchist periodical published,[143] an enterprise for which he built his own printing press, cast his own type and made his own printing plates.[143]

Catalan historian Xavier Diez reports that the intentional communal experiments pioneered by Warren were influential in European individualist anarchists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries such as Émile Armand and the intentional communities started by them.[205] Warren said that Stephen Pearl Andrews, individualist anarchist and close associate, wrote the most lucid and complete exposition of Warren's own theories in The Science of Society, published in 1852.[206] Andrews was formerly associated with the Fourierist movement, but converted to radical individualism after becoming acquainted with the work of Warren. Like Warren, he held the principle of "individual sovereignty" as being of paramount importance. Contemporary American anarchist Hakim Bey reports:

Steven Pearl Andrews [...] was not a Fourierist, but he lived through the brief craze for phalansteries in America and adopted a lot of Fourierist principles and practices [...], a maker of worlds out of words. He syncretized abolitionism in the United States, free love, spiritual universalism, Warren, and Fourier into a grand utopian scheme he called the Universal Pantarchy. [...] He was instrumental in founding several 'intentional communities,' including the 'Brownstone Utopia' on 14th St. in New York, and 'Modern Times' in Brentwood, Long Island. The latter became as famous as the best-known Fourierist communes (Brook Farm in Massachusetts & the North American Phalanx in New Jersey)—in fact, Modern Times became downright notorious (for 'Free Love') and finally foundered under a wave of scandalous publicity. Andrews (and Victoria Woodhull) were members of the infamous Section 12 of the 1st International, expelled by Marx for its anarchist, feminist, and spiritualist tendencies.[207]

For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, "[i]t is apparent that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form".[208] William Batchelder Greene was a 19th-century mutualist individualist anarchist, Unitarian minister, soldier and promoter of free banking in the United States. Greene is best known for the works Mutual Banking, which proposed an interest-free banking system; and Transcendentalism, a critique of the New England philosophical school. After 1850, he became active in labor reform.[208] He was elected vice president of the New England Labor Reform League, "the majority of the members holding to Proudhon's scheme of mutual banking, and in 1869 president of the Massachusetts Labor Union".[208] Greene then published Socialistic, Mutualistic, and Financial Fragments (1875).[208] He saw mutualism as the synthesis of "liberty and order".[208] His "associationism [...] is checked by individualism. [...] 'Mind your own business,' 'Judge not that ye be not judged.' Over matters which are purely personal, as for example, moral conduct, the individual is sovereign, as well as over that which he himself produces. For this reason he demands 'mutuality' in marriage—the equal right of a woman to her own personal freedom and property".[208]

Poet, naturalist and transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau was an important early influence in individualist anarchist thought in the United States and Europe. He is best known for his book Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings; and his essay Civil Disobedience (Resistance to Civil Government), an argument for individual resistance to civil government in moral opposition to an unjust state. In Walden, Thoreau advocates simple living and self-sufficiency among natural surroundings in resistance to the advancement of industrial civilization.[209] Civil Disobedience, first published in 1849, argues that people should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy their consciences and that people have a duty to avoid allowing such acquiescence to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice. These works influenced green anarchism, anarcho-primitivism and anarcho-pacifism[210] as well as figures including Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Martin Buber and Leo Tolstoy.[210] For George Woodcock, this attitude can be also motivated by certain idea of resistance to progress and of rejection of the growing materialism which is the nature of American society in the mid-19th century".[209] Zerzan included Thoreau's "Excursions" in his edited compilation of anti-civilization writings, Against Civilization: Readings and Reflections.[211] Individualist anarchists such as Thoreau[212][213] do not speak of economics, but simply the right of disunion from the state and foresee the gradual elimination of the state through social evolution. Agorist author J. Neil Schulman cites Thoreau as a primary inspiration.[214]

Many economists since Adam Smith have argued that—unlike other taxes—a land value tax would not cause economic inefficiency.[215] It would be a progressive tax,[216] i.e. a tax paid primarily by the wealthy, that increases wages, reduces economic inequality, removes incentives to misuse real estate and reduces the vulnerability that economies face from credit and property bubbles.[217][218] Early proponents of this view include Thomas Paine, Herbert Spencer and Hugo Grotius,[219] but the concept was widely popularized by the economist and social reformer Henry George.[220] George believed that people ought to own the fruits of their labor and the value of the improvements they make and therefore he was opposed to income taxes, sales taxes, taxes on improvements and all other taxes on production, labor, trade or commerce. George was among the staunchest defenders of free markets and his book Protection or Free Trade was read into the Congressional Record.[221] Nonetheless, he did support direct management of natural monopolies such as right-of-way monopolies necessary for railroads as a last resort and advocated for elimination of intellectual property arrangements in favor of government sponsored prizes for inventors. In Progress and Poverty, George argued: "Our boasted freedom necessarily involves slavery, so long as we recognize private property in land. Until that is abolished, Declarations of Independence and Acts of Emancipation are in vain. So long as one man can claim the exclusive ownership of the land from which other men must live, slavery will exist, and as material progress goes on, must grow and deepen!"[222] Early followers of George's philosophy called themselves single taxers because they believed that the only legitimate, broad-based tax was land rent. The term Georgism was coined later, though some modern proponents prefer the term geoism instead,[223] leaving the meaning of geo (Earth in Greek) deliberately ambiguous. The terms Earth Sharing,[224] geonomics[225] and geolibertarianism[226] are used by some Georgists to represent a difference of emphasis, or real differences about how land rent should be spent, but all agree that land rent should be recovered from its private owners.

Individualist anarchism found in the United States an important space for discussion and development within the group known as the Boston anarchists.[227] Even among the 19th-century American individualists there was no monolithic doctrine and they disagreed amongst each other on various issues including intellectual property rights and possession versus property in land.[228][229][230] Some Boston anarchists, including Benjamin Tucker, identified as socialists, which in the 19th century was often used in the sense of a commitment to improving conditions of the working class (i.e. "the labor problem").[231] Lysander Spooner, besides his individualist anarchist activism, was also an anti-slavery activist and member of the First International.[232] Tucker argued that the elimination of what he called "the four monopolies"—the land monopoly, the money and banking monopoly, the monopoly powers conferred by patents and the quasi-monopolistic effects of tariffs—would undermine the power of the wealthy and big business, making possible widespread property ownership and higher incomes for ordinary people, while minimizing the power of would-be bosses and achieving socialist goals without state action. Tucker's anarchist periodical, Liberty, was published from August 1881 to April 1908.

The publication Liberty, emblazoned with Proudhon's quote that liberty is "Not the Daughter But the Mother of Order" was instrumental in developing and formalizing the individualist anarchist philosophy through publishing essays and serving as a forum for debate. Contributors included Benjamin Tucker, Lysander Spooner, Auberon Herbert, Dyer Lum, Joshua K. Ingalls, John Henry Mackay, Victor Yarros, Wordsworth Donisthorpe, James L. Walker, J. William Lloyd, Florence Finch Kelly, Voltairine de Cleyre, Steven T. Byington, John Beverley Robinson, Jo Labadie, Lillian Harman and Henry Appleton.[233] Later, Tucker and others abandoned their traditional support of natural rights and converted to an egoism modeled upon the philosophy of Max Stirner.[229] A number of natural rights proponents stopped contributing in protest. Several periodicals were undoubtedly influenced by Liberty's presentation of egoism, including I published by Clarence Lee Swartz and edited by William Walstein Gordak and J. William Lloyd (all associates of Liberty); and The Ego and The Egoist, both of which were edited by Edward H. Fulton. Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed were the German Der Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand; and The Eagle and The Serpent, issued from London. The latter, the most prominent English language egoist journal, was published from 1898 to 1900 with the subtitle A Journal of Egoistic Philosophy and Sociology.[234][235]

Georgism and geolibertarianism[edit]

Henry George, influential among left-libertarians, advocated that the value derived from land should belong to all members of a society Henry George was an American political economist and journalist who advocated that all economic value derived from land, including natural resources, should belong equally to all members of society. Strongly opposed to feudalism and the privatisation of land, George created the philosophy of Georgism, or geoism, influential among many left-libertarians, including geolibertarians and geoanarchists. Much like the English Digger movement, who held all material possessions in common, George claimed that land and its financial properties belong to everyone, and that to hold land as private property would lead to immense inequalities, including authority from the private owners of such ground.

Prior to states assigning property owners slices of either once populated or uninhabited land, the world's earth was held in common. When all resources that derive from land are put to achieving a higher quality of life, not just for employers or landlords, but to serve the general interests and comforts of a wider community, Geolibertarians claim vastly higher qualities of life can be reached, especially with ever advancing technology and industrialised agriculture.

The Diggers, early libertarian communists, held all things in common, including land which was often violently seized by the European aristocracy The Levellers, also known as the Diggers, were a 17th-century anti-authoritarian movement that stood in resistance to the English government and the feudalism it was pushing through the forced privatisation of land known as the enclosure around the time of the First English Civil War. Devout Protestants, Gerrard Winstanley was a prominent member of the community and with a very progressive interpretation of his religion sought to end buying and selling, instead for all inhabitants of a society to share their material possessions and to hold all things in common, without money or payment. With the complete abolition of private property, including that of private land, the English Levellers created a pool of property where all properties belonged in equal measure to everyone. Often seen as some of the first practising anarchists, the Digger movement is considered Christian communist and extremely early libertarian communism.

Modern libertarianism in the United States[edit]

By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed.[236] H. L. Mencken and Albert Jay Nock were the first prominent figures in the United States to describe themselves as libertarian as synonym for liberal. They believed that Franklin D. Roosevelt had co-opted the word liberal for his New Deal policies which they opposed and used libertarian to signify their allegiance to classical liberalism, individualism and limited government.[237] In 1914, Nock joined the staff of The Nation magazine which at the time was supportive of liberal capitalism. A lifelong admirer of Henry George, Nock went on to become co-editor of The Freeman from 1920 to 1924, a publication initially conceived as a vehicle for the single tax movement, financed by the wealthy wife of the magazine's other editor Francis Neilson.[238] Critic H. L. Mencken wrote that "[h]is editorials during the three brief years of the Freeman set a mark that no other man of his trade has ever quite managed to reach. They were well-informed and sometimes even learned, but there was never the slightest trace of pedantry in them".[239]

Executive Vice President of the Cato Institute David Boaz wrote: "In 1943, at one of the lowest points for liberty and humanity in history, three remarkable women published books that could be said to have given birth to the modern libertarian movement".[240] Isabel Paterson's The God of the Machine, Rose Wilder Lane's The Discovery of Freedom and Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead each promoted individualism and capitalism. None of the three used the term libertarianism to describe their beliefs and Rand specifically rejected the label, criticizing the burgeoning American libertarian movement as the "hippies of the right".[241] Rand's own philosophy of Objectivism is notedly similar to libertarianism and she accused libertarians of plagiarizing her ideas.[241] Rand stated:

All kinds of people today call themselves "libertarians," especially something calling itself the New Right, which consists of hippies who are anarchists instead of leftist collectivists; but anarchists are collectivists. Capitalism is the one system that requires absolute objective law, yet libertarians combine capitalism and anarchism. That's worse than anything the New Left has proposed. It's a mockery of philosophy and ideology. They sling slogans and try to ride on two bandwagons. They want to be hippies, but don't want to preach collectivism because those jobs are already taken. But anarchism is a logical outgrowth of the anti-intellectual side of collectivism. I could deal with a Marxist with a greater chance of reaching some kind of understanding, and with much greater respect. Anarchists are the scum of the intellectual world of the Left, which has given them up. So the Right picks up another leftist discard. That's the libertarian movement.[242]

In 1946, Leonard E. Read founded the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE), an American nonprofit educational organization which promotes the principles of laissez-faire economics, private property and limited government.[243] According to Gary North, former FEE director of seminars and a current Mises Institute scholar, the FEE is the "granddaddy of all libertarian organizations".[244] The initial officers of the FEE were Leonard E. Read as president, Austrian School economist Henry Hazlitt as vice president and David Goodrich of B. F. Goodrich as chairman. Other trustees on the FEE board have included wealthy industrialist Jasper Crane of DuPont, H. W. Luhnow of William Volker & Co. and Robert W. Welch Jr., founder of the John Birch Society.[246][247]

Austrian School economist Murray Rothbard was initially an enthusiastic partisan of the Old Right, particularly because of its general opposition to war and imperialism,[248] but long embraced a reading of American history that emphasized the role of elite privilege in shaping legal and political institutions. He was part of Ayn Rand's circle for a brief period, but later harshly criticized Objectivism.[249] He praised Rand's Atlas Shrugged and wrote that she "introduced me to the whole field of natural rights and natural law philosophy", prompting him to learn "the glorious natural rights tradition".[250] He soon broke with Rand over various differences, including his defense of anarchism, calling his philosophy anarcho-capitalism. Rothbard was influenced by the work of the 19th-century American individualist anarchists[251] and sought to meld their advocacy of free markets and private defense with the principles of Austrian economics.[252]

Karl Hess, a speechwriter for Barry Goldwater and primary author of the Republican Party's 1960 and 1964 platforms, became disillusioned with traditional politics following the 1964 presidential campaign in which Goldwater lost to Lyndon B. Johnson. He parted with the Republicans altogether after being rejected for employment with the party, and began work as a heavy-duty welder. Hess began reading American anarchists largely due to the recommendations of his friend Murray Rothbard and said that upon reading the works of communist anarchist Emma Goldman, he discovered that anarchists believed everything he had hoped the Republican Party would represent. For Hess, Goldman was the source for the best and most essential theories of Ayn Rand without any of the "crazy solipsism that Rand was so fond of".[253] Hess and Rothbard founded the journal Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought, which was published from 1965 to 1968, with George Resch and Leonard P. Liggio. In 1969, they edited The Libertarian Forum which Hess left in 1971. Hess eventually put his focus on the small scale, stating that society is "people together making culture". He deemed two of his cardinal social principles to be "opposition to central political authority" and "concern for people as individuals". His rejection of standard American party politics was reflected in a lecture he gave during which he said: "The Democrats or liberals think that everybody is stupid and therefore they need somebody [...] to tell them how to behave themselves. The Republicans think everybody is lazy".[254]

The Nolan Chart, created by American libertarian David Nolan, expands the left–right line into a two-dimensional chart classifying the political spectrum by degrees of personal and economic freedom The Vietnam War split the uneasy alliance between growing numbers of American libertarians and conservatives who believed in limiting liberty to uphold moral virtues. Libertarians opposed to the war joined the draft resistance and peace movements as well as organizations such as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). In 1969 and 1970, Hess joined with others, including Murray Rothbard, Robert LeFevre, Dana Rohrabacher, Samuel Edward Konkin III and former SDS leader Carl Oglesby to speak at two conferences which brought together activists from both the New Left and the Old Right in what was emerging as a nascent libertarian movement.[255] As part of his effort to unite the left and right wings of libertarianism, Hess would join both the SDS and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), of which he explained: "We used to have a labor movement in this country, until I.W.W. leaders were killed or imprisoned. You could tell labor unions had become captive when business and government began to praise them. They're destroying the militant black leaders the same way now. If the slaughter continues, before long liberals will be asking, 'What happened to the blacks? Why aren't they militant anymore?'"[256] Rothbard ultimately broke with the left, allying himself with the burgeoning paleoconservative movement.[257][258] He criticized the tendency of these libertarians to appeal to "'free spirits,' to people who don't want to push other people around, and who don't want to be pushed around themselves" in contrast to "the bulk of Americans" who "might well be tight-assed conformists, who want to stamp out drugs in their vicinity, kick out people with strange dress habits, etc." Rothbard emphasized that this was relevant as a matter of strategy as the failure to pitch the libertarian message to Middle America might result in the loss of "the tight-assed majority".[259][260] This left-libertarian tradition[261] has been carried to the present day by Konkin III's agorists,[262] contemporary mutualists such as Kevin Carson,[263] Roderick T. Long[264] and others such as Gary Chartier[265] Charles W. Johnson[266][267] Sheldon Richman,[78] Chris Matthew Sciabarra[268] and Brad Spangler.[269]

In 1971, a small group of Americans led by David Nolan formed the Libertarian Party,[270] which has run a presidential candidate every election year since 1972. Other libertarian organizations, such as the Center for Libertarian Studies and the Cato Institute, were also formed in the 1970s.[271] Philosopher John Hospers, a one-time member of Rand's inner circle, proposed a non-initiation of force principle to unite both groups, but this statement later became a required "pledge" for candidates of the Libertarian Party and Hospers became its first presidential candidate in 1972.[272] In the 1980s, Hess joined the Libertarian Party and served as editor of its newspaper from 1986 to 1990. According to Maureen Tkacik, Hess moved to the radical left[273] and was the ideological grandfather of the anti-1% and pro-99% movement, the direct antecedent of thinkers like Ron Paul and both the Tea Party movement and the Occupy movement.[274]

Modern libertarianism gained significant recognition in academia with the publication of Harvard University professor Robert Nozick's Anarchy, State, and Utopia in 1974, for which he received a National Book Award in 1975.[275] In response to John Rawls's A Theory of Justice, Nozick's book supported a minimal state (also called a nightwatchman state by Nozick) on the grounds that the ultraminimal state arises without violating individual rights[276] and the transition from an ultraminimal state to a minimal state is morally obligated to occur. Specifically, Nozick wrote: "We argue that the first transition from a system of private protective agencies to an ultraminimal state, will occur by an invisible-hand process in a morally permissible way that violates no one's rights. Secondly, we argue that the transition from an ultraminimal state to a minimal state morally must occur. It would be morally impermissible for persons to maintain the monopoly in the ultraminimal state without providing protective services for all, even if this requires specific 'redistribution.' The operators of the ultraminimal state are morally obligated to produce the minimal state".[277]

In the early 1970s, Rothbard wrote: "One gratifying aspect of our rise to some prominence is that, for the first time in my memory, we, 'our side,' had captured a crucial word from the enemy. 'Libertarians' had long been simply a polite word for left-wing anarchists, that is for anti-private property anarchists, either of the communist or syndicalist variety. But now we had taken it over".[278] The project of spreading libertarian ideals in the United States has been so successful that some Americans who do not identify as libertarian seem to hold libertarian views.[279] Since the resurgence of neoliberalism in the 1970s, this modern American libertarianism has spread beyond North America via think tanks and political parties.[280][281]

Contemporary libertarianism[edit]

Contemporary libertarian socialism[edit]

A surge of popular interest in libertarian socialism occurred in Western nations during the 1960s and 1970s.[282] Anarchism was influential in the counterculture of the 1960s[283][284][285] and anarchists actively participated in the protests of 1968 which included students and workers' revolts.[286] In 1968, the International of Anarchist Federations was founded in Carrara, Italy during an international anarchist conference held there in 1968 by the three existing European federations of France, the Italian and the Iberian Anarchist Federation as well as the Bulgarian Anarchist Federation in French exile.[181][287] The uprisings of May 1968 also led to a small resurgence of interest in left communist ideas. Various small left communist groups emerged around the world, predominantly in the leading capitalist countries. A series of conferences of the communist left began in 1976, with the aim of promoting international and cross-tendency discussion, but these petered out in the 1980s without having increased the profile of the movement or its unity of ideas.[288] Left communist groups existing today include the International Communist Party, International Communist Current and the Internationalist Communist Tendency. The housing and employment crisis in most of Western Europe led to the formation of communes and squatter movements like that of Barcelona in Spain. In Denmark, squatters occupied a disused military base and declared the Freetown Christiania, an autonomous haven in central Copenhagen.

Around the turn of the 21st century, libertarian socialism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war, anti-capitalist and anti-globalisation movements.[289] Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against the meetings of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Group of Eight and the World Economic Forum. Some anarchist factions at these protests engaged in rioting, property destruction and violent confrontations with police. These actions were precipitated by ad hoc, leaderless, anonymous cadres known as black blocs and other organizational tactics pioneered in this time include security culture, affinity groups and the use of decentralized technologies such as the Internet.[289] A significant event of this period was the confrontations at WTO conference in Seattle in 1999.[289] For English anarchist scholar Simon Critchley, "contemporary anarchism can be seen as a powerful critique of the pseudo-libertarianism of contemporary neo-liberalism. One might say that contemporary anarchism is about responsibility, whether sexual, ecological or socio-economic; it flows from an experience of conscience about the manifold ways in which the West ravages the rest; it is an ethical outrage at the yawning inequality, impoverishment and disenfranchisment that is so palpable locally and globally".[290] This might also have been motivated by "the collapse of 'really existing socialism' and the capitulation to neo-liberalism of Western social democracy".[291]

Libertarian socialists in the early 21st century have been involved in the alter-globalization movement, squatter movement; social centers; infoshops; anti-poverty groups such as Ontario Coalition Against Poverty and Food Not Bombs; tenants' unions; housing cooperatives; intentional communities generally and egalitarian communities; anti-sexist organizing; grassroots media initiatives; digital media and computer activism; experiments in participatory economics; anti-racist and anti-fascist groups like Anti-Racist Action and Anti-Fascist Action; activist groups protecting the rights of immigrants and promoting the free movement of people such as the No Border network; worker co-operatives, countercultural and artist groups; and the peace movement.

Contemporary libertarianism in the United States[edit]

In the United States, polls (circa 2006) find that the views and voting habits of between 10% and 20%, or more, of voting age Americans may be classified as "fiscally conservative and socially liberal, or libertarian".[53][91] This is based on pollsters and researchers defining libertarian views as fiscally conservative and socially liberal (based on the common United States meanings of the terms) and against government intervention in economic affairs and for expansion of personal freedoms.[53] In a 2015 Gallup poll this figure had risen to 27%.[97] A 2015 Reuters poll found that 23% of American voters self-identify as libertarians, including 32% in the 18–29 age group.[96] Through twenty polls on this topic spanning thirteen years, Gallup found that voters who are libertarian on the political spectrum ranged from 17–23% of the United States electorate.[94] However, a 2014 Pew Poll found that 23% of Americans who identify as libertarians have no idea what the word means.[95]

2009 saw the rise of the Tea Party movement, an American political movement known for advocating a reduction in the United States national debt and federal budget deficit by reducing government spending and taxes, which had a significant libertarian component[292] despite having contrasts with libertarian values and views in some areas such as free trade, immigration, nationalism and social issues.[293] A 2011 Reason-Rupe poll found that among those who self-identified as Tea Party supporters, 41 percent leaned libertarian and 59 percent socially conservative.[294] Named after the Boston Tea Party, it also contains conservative[295][296][297] and populist elements[298][299][300] and has sponsored multiple protests and supported various political candidates since 2009. Tea Party activities have declined since 2010 with the number of chapters across the country slipping from about 1,000 to 600.[301][302] Mostly, Tea Party organizations are said to have shifted away from national demonstrations to local issues.[301] Following the selection of Paul Ryan as Mitt Romney's 2012 vice presidential running mate, The New York Times declared that Tea Party lawmakers are no longer a fringe of the conservative coalition, but now "indisputably at the core of the modern Republican Party".[303]

In 2012, anti-war and pro-drug liberalization presidential candidates such as Libertarian Republican Ron Paul and Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson raised millions of dollars and garnered millions of votes despite opposition to their obtaining ballot access by both Democrats and Republicans.[304] The 2012 Libertarian National Convention saw Johnson and Jim Gray being nominated as the 2012 presidential ticket for the Libertarian Party, resulting in the most successful result for a third-party presidential candidacy since 2000 and the best in the Libertarian Party's history by vote number. Johnson received 1% of the popular vote, amounting to more than 1.2 million votes.[305][306] Johnson has expressed a desire to win at least 5 percent of the vote so that the Libertarian Party candidates could get equal ballot access and federal funding, thus subsequently ending the two-party system.[307][308][309] The 2016 Libertarian National Convention saw Johnson and Bill Weld nominated as the 2016 presidential ticket and resulted in the most successful result for a third-party presidential candidacy since 1996 and the best in the Libertarian Party's history by vote number. Johnson received 3% of the popular vote, amounting to more than 4.3 million votes.[310]

Contemporary libertarian organizations[edit]

Current international anarchist federations which identify themselves as libertarian include the International of Anarchist Federations, the International Workers' Association and International Libertarian Solidarity. The largest organized anarchist movement today is in Spain, in the form of the Confederación General del Trabajo (CGT) and the CNT. CGT membership was estimated to be around 100,000 for 2003.[311] Other active syndicalist movements include the Central Organisation of the Workers of Sweden and the Swedish Anarcho-syndicalist Youth Federation in Sweden; the Unione Sindacale Italiana in Italy; Workers Solidarity Alliance in the United States; and Solidarity Federation in the United Kingdom. The revolutionary industrial unionist Industrial Workers of the World claiming 2,000 paying members as well as the International Workers' Association, remain active. In the United States, there exists the Common Struggle – Libertarian Communist Federation.

Since the 1950s, many American libertarian organizations have adopted a free-market stance as well as supporting civil liberties and non-interventionist foreign policies. These include the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Francisco Marroquín University, the Foundation for Economic Education, Center for Libertarian Studies, the Cato Institute and Liberty International. The activist Free State Project, formed in 2001, works to bring 20,000 libertarians to New Hampshire to influence state policy.[312] Active student organizations include Students for Liberty and Young Americans for Liberty. A number of countries have libertarian parties that run candidates for political office. In the United States, the Libertarian Party was formed in 1972 and is the third largest[313][314] American political party, with 511,277 voters (0.46% of total electorate) registered as Libertarian in the 31 states that report Libertarian registration statistics and Washington, D.C.[315]

Criticism[edit]

Criticism of libertarianism includes ethical, economic, environmental, pragmatic and philosophical concerns, especially in relation to right-libertarianism,[316][317][318][319][320][321] including the view that it has no explicit theory of liberty.[49] It has been argued that laissez-faire capitalism does not necessarily produce the best or most efficient outcome,[322][323] nor does its philosophy of individualism and policies of deregulation prevent the abuse of natural resources.[324] Critics such as Corey Robin describe this type of libertarianism as fundamentally a reactionary conservative ideology united with more traditionalist conservative thought and goals by a desire to enforce hierarchical power and social relations.[70]

Similarly, Nancy MacLean has argued that libertarianism is a radical right ideology that has stood against democracy. According to MacLean, libertarian-leaning Charles and David Koch have used anonymous, dark money campaign contributions, a network of libertarian institutes and lobbying for the appointment of libertarian, pro-business judges to United States federal and state courts to oppose taxes, public education, employee protection laws, environmental protection laws and the New Deal Social Security program.[325]

Moral and pragmatic criticism of libertarianism also includes allegations of utopianism,[326] tacit authoritarianism[327][328] and vandalism towards feats of civilisation.[329]

Allegation of utopianism[edit]

Libertarian philosophies such as anarchism are evaluated as unfeasible or utopian by their critics, often in general and formal debate. European history professor Carl Landauer argued that anarchy is unrealistic and that government is a "lesser evil" than a society without "repressive force". He also argued that "ill intentions will cease if repressive force disappears" is an "absurdity".[326] In response, An Anarchist FAQ states the following: "Anarchy is not a utopia, [and] anarchists make no such claims about human perfection. [...] Remaining disputes would be solved by reasonable methods, for example, the use of juries, mutual third parties, or community and workplace assemblies". It also states that "some sort of 'court' system would still be necessary to deal with the remaining crimes and to adjudicate disputes between citizens".[330]

Government decentralization[edit]

John Donahue argues that if political power were radically shifted to local authorities, parochial local interests would predominate at the expense of the whole and that this would exacerbate current problems with collective action.[331]

Before Donahue, Friedrich Engels claimed in his essay On Authority that radical decentralization would destroy modern industrial civilization, citing an example of railways:[329]

Here too the co-operation of an infinite number of individuals is absolutely necessary, and this co-operation must be practised during precisely fixed hours so that no accidents may happen. Here, too, the first condition of the job is a dominant will that settles all subordinate questions, whether this will is represented by a single delegate or a committee charged with the execution of the resolutions of the majority of persona interested. In either case there is a very pronounced authority. Moreover, what would happen to the first train dispatched if the authority of the railway employees over the Hon. passengers were abolished?

In the end, it is argued that authority in any form is a natural occurrence which should not be abolished.[332]

Lack of real-world examples[edit]

Michael Lind has observed that of the 195 countries in the world today, none have fully actualized a society as advocated by American libertarians:

If libertarianism was a good idea, wouldn't at least one country have tried it? Wouldn't there be at least one country, out of nearly two hundred, with minimal government, free trade, open borders, decriminalized drugs, no welfare state and no public education system?[333]

Furthermore, Lind has criticized libertarianism in the United States as being incompatible with democracy and apologetic towards autocracy.[334] In response, American libertarian Warren Redlich argues that the United States "was extremely libertarian from the founding until 1860, and still very libertarian until roughly 1930".[335]

A recent real-world example is the Free Town Project, based in Grafton, New Hampshire. As part of the Free State Project, the Free Town Project promoted libertarians moving to Grafton and becoming involved in local politics. They successfully changed a number of the laws and regulations in the small community, reducing taxation and corresponding services. The effect on the community was mixed and has been analyzed in books[336] and articles.[337]

Tacit authoritarianism[edit]

The libertarian tendency within anarchism known as platformism has been criticized by other libertarians of preserving tacitly authoritarian, bureaucratic or statist tendencies.[327][328]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Boaz, David (30 January 2009). "Libertarianism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

[L]ibertarianism, political philosophy that takes individual liberty to be the primary political value.

- ^ Woodcock, George (2004) [1962]. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Peterborough: Broadview Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781551116297.

[F]or the very nature of the libertarian attitude—its rejection of dogma, its deliberate avoidance of rigidly systematic theory, and, above all, its stress on extreme freedom of choice and on the primacy of the individual judgement [sic].

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Long, Joseph. W (1996). "Toward a Libertarian Theory of Class". Social Philosophy and Policy. 15 (2): 310. "When I speak of 'libertarianism' [...] I mean all three of these very different movements. It might be protested that LibCap [libertarian capitalism], LibSoc [libertarian socialism] and LibPop [libertarian populism] are too different from one another to be treated as aspects of a single point of view. But they do share a common—or at least an overlapping—intellectual ancestry."