Enoch

Enoch the Patriarch | |

|---|---|

God took Enoch, as in Genesis 5:24: "And Enoch walked with God, and he was not; for God took him".[1] illustration from the 1728 Figures de la Bible; illustrated by Gerard Hoet | |

| Antediluvian Patriarch | |

| Born | 622 AM Babylon |

| Died | 987 AM ("taken up by God" as per traditions) |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Oriental Orthodoxy Eastern Orthodoxy Enochian Christian sects (see John Dee) Islam Medieval Rabbinical Judaism Baháʼí Faith Some New Age cults devoted to angelology |

| Feast | Sunday before the Nativity of Christ in the Eastern Orthodox Church, 30 July, 22 January in the Coptic Church, 19 July (his assumption in the Coptic Church), 3 January (Bollandists)[2] |

Enoch (/ˈiːnək/ (![]() listen))[a] is a biblical figure and patriarch prior to Noah's flood, and the son of Jared and father of Methuselah. He was of the Antediluvian period in the Hebrew Bible.

listen))[a] is a biblical figure and patriarch prior to Noah's flood, and the son of Jared and father of Methuselah. He was of the Antediluvian period in the Hebrew Bible.

The text of the Book of Genesis says Enoch lived 364 years before he was taken by God. The text reads that Enoch "walked with God: and he was no more; for God took him" (Gen 5:21–24), which is interpreted as Enoch's entering heaven alive in some Jewish and Christian traditions, and interpreted differently in others.[citation needed]

Enoch is the subject of many Jewish and Christian traditions. He was considered the author of the Book of Enoch[3] and also called the scribe of judgment.[4] In the New Testament, Enoch is referenced in the Gospel of Luke, the Epistle to the Hebrews, and in the Epistle of Jude, the last of which also quotes from it.[5] In the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Oriental Orthodoxy, he is venerated as a saint. In Islam, Enoch is identified with Idris (Arabic: إدريس, romanized: ʾIdrīs) and is considered a prophet.

The name of Enoch (Hebrew: חֲנוֹךְ Ḥănōḵ) derives from the Hebrew root חנך (ḥ-n-ḵ), meaning to train, initiate, dedicate, inaugurate,[6] with חֲנוֹךְ/חֲנֹךְ (Ḥănōḵ) being the imperative form of the verb.[7][8]

Enoch in the Book of Genesis[edit]

Enoch appears in the Book of Genesis of the Pentateuch as the seventh of the ten pre-Deluge Patriarchs. Genesis recounts that each of the pre-Flood Patriarchs lived for several centuries. Genesis 5 provides a genealogy of these ten figures (from Adam to Noah), providing the age at which each fathered the next, and the age of each figure at death. Enoch is considered by many to be the exception, who is said to "not see death" (Hebrews 11:5). Furthermore, Genesis 5:22–24 states that Enoch lived for 364 years, which is shorter than other pre-Flood Patriarchs, who are all recorded as dying at over 700 years of age. The brief account of Enoch in Genesis 5 ends with the cryptic note that "he was not; for God took him".[9] This happens 57 years after Adam's death and 69 years before Noah's birth.

Apocryphal Books of Enoch[edit]

Three extensive Apocrypha are attributed to Enoch:

- The Book of Enoch (aka 1 Enoch), composed in Hebrew or Aramaic and preserved in Ge'ez, first brought to Europe by James Bruce from Ethiopia and translated into English by August Dillmann and Reverent Schoode[10] – recognized by the Orthodox Tewahedo churches and usually dated between the third century BC and the first century AD.

- 2 Enoch (aka Book of the Secrets of Enoch), preserved in Old Church Slavonic, and first translated in English by William Morfill[11] – usually dated to the first century AD.

- 3 Enoch, a Rabbinic text in Hebrew usually dated to the fifth century AD.

These recount how Enoch was taken up to Heaven and was appointed guardian of all the celestial treasures, chief of the archangels, and the immediate attendant on the Throne of God. He was subsequently taught all secrets and mysteries and, with all the angels at his back, fulfils of his own accord whatever comes out of the mouth of God, executing His decrees. Some esoteric literature, such as 3 Enoch, identifies Enoch as Metatron, the angel which communicates God's word. In consequence, Enoch was seen, by this literature and the Rabbinic kabbalah of Jewish mysticism, as the one who communicated God's revelation to Moses, and, in particular, as the dictator of the Book of Jubilees.

Enoch in Book of Giants[edit]

The Book of Giants is a Jewish pseudepigraphal work from the third century BC and resembles the Book of Enoch. Fragments from at least six and as many as eleven copies were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls collections.[12]

Septuagint[edit]

The third-century BC translators who produced the Septuagint in Koine Greek rendered the phrase "God took him" with the Greek verb metatithemi (μετατίθημι)[13] meaning moving from one place to another.[14] Sirach 44:16, from about the same period, states that "Enoch pleased God and was translated into paradise that he may give repentance to the nations." The Greek word used here for paradise, paradeisos (παράδεισος), was derived from an ancient Persian word meaning "enclosed garden", and was used in the Septuagint to describe the garden of Eden. Later, however, the term became synonymous for heaven, as is the case here.[15]

Enoch in classical Rabbinical literature[edit]

In classical Rabbinical literature, there are various views of Enoch. One view regarding Enoch that was found in the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, which thought of Enoch as a pious man, taken to Heaven, and receiving the title of Safra rabba (Great scribe). After Christianity was completely separated from Judaism, this view became the prevailing rabbinical idea of Enoch's character and exaltation.[16]

According to Rashi[17] [from Genesis Rabbah[18]], "Enoch was a righteous man, but he could easily be swayed to return to do evil. Therefore, the Holy One, blessed be He, hastened and took him away and caused him to die before his time. For this reason, Scripture changed [the wording] in [the account of] his demise and wrote, 'and he was no longer' in the world to complete his years."

Among the minor Midrashim, esoteric attributes of Enoch are expanded upon. In the Sefer Hekalot, Rabbi Ishmael is described as having visited the Seventh Heaven, where he met Enoch, who claims that earth had, in his time, been corrupted by the demons Shammazai, and Azazel, and so Enoch was taken to Heaven to prove that God was not cruel.[16] Similar traditions are recorded in Sirach. Later elaborations of this interpretation treated Enoch as having been a pious ascetic, who, called to mix with others, preached repentance, and gathered (despite the small number of people on Earth) a vast collection of disciples, to the extent that he was proclaimed king. Under his wisdom, peace is said to have reigned on earth, to the extent that he is summoned to Heaven to rule over the sons of God.

Enoch in Christianity[edit]

New Testament[edit]

The New Testament contains three references to Enoch.

- The first is a brief mention in one of the genealogies of the ancestors of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke. (Luke 3:37).

- The second mention is in the Epistle to the Hebrews which says, "By faith Enoch was translated that he should not see death; and was not found, because God had translated him: for before his translation he had this testimony, that he pleased God." (Hebrews 11:5 KJV). This suggests he did not experience the mortal death ascribed to Adam's other descendants, which is consistent with Genesis 5:24 KJV, which says, "And Enoch walked with God: and he [was] not; for God took him."

- The third mention is in the Epistle of Jude (1:14–15) where the author attributes to "Enoch, the Seventh from Adam" a passage not found in Catholic and Protestant canons of the Old Testament. The quotation is believed by most modern scholars to be taken from 1 Enoch 1:9 which exists in Greek, in Ge'ez (as part of the Ethiopian Orthodox canon), and also in Aramaic among the Dead Sea Scrolls.[19][20] Though the same scholars recognise that 1 Enoch 1:9 itself is a midrash of Deuteronomy 33:2.[21][22][23][24][25]

The introductory phrase "Enoch, the Seventh from Adam" is also found in 1 Enoch (1 En. 60:8), though not in the Old Testament.[26] In the New Testament this Enoch prophesies "to"[b] ungodly men, that God shall come with His holy ones to judge and convict them (Jude 1:14–15).

Influence in Christianity[edit]

The Book of Enoch was excluded from both the Hebrew Tanakh and the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, the Septuagint. It was not considered canon by either Jewish or early Christian readers. Church Fathers such as Justin Martyr, Athenagoras of Athens, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Tertullian, and Lactantius all speak highly of Enoch and contain many allusions to the Book of Enoch as well as in some instances advocating explicitly for the use of the Book of Enoch as Scripture.[30][31][32][33][34][35] Because of the letter of Jude's citation of the Book of Enoch as prophetic text, this encouraged acceptance and usage of the Book of Enoch in early Christian circles. The main themes of Enoch about the Watchers corrupting humanity were commonly mentioned in early literature. This positive treatment of the Book of Enoch was associated with millennialism which was popular in the early Church. When amillennialism began to be common in Christianity, the Book of Enoch, being incompatible with amillennialism, came to be widely rejected. After the split of the Oriental Orthodox Church from the Catholic Church in the 5th century, use of the Book of Enoch was limited primarily to the Oriental Orthodox Church. Eventually, the usage of the Book of Enoch became limited to Ethiopian circles of the Oriental Orthodox Church. Another common element that some Church Fathers, like John of Damascus, spoke of, was that they considered Enoch to be one of the two witnesses mentioned in the Book of Revelation. This view still has many supporters today in Christianity.

In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints theology[edit]

Among the Latter Day Saint movement and particularly in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Enoch is viewed as having founded an exceptionally righteous city, named Zion, in the midst of an otherwise wicked world. This view is encountered in the standard works, the Pearl of Great Price and the Doctrine and Covenants, which states that not only Enoch, but the entire peoples of the city of Zion, were taken off this earth without death, because of their piety. (Zion is defined as "the pure in heart" and this city of Zion will return to the earth at the Second Coming of Jesus.) The Doctrine and Covenants further states that Enoch prophesied that one of his descendants, Noah, and his family, would survive a Great Flood and thus carry on the human race and preserve the Scripture. The Book of Moses in the Pearl of Great Price includes chapters that give an account of Enoch's preaching, visions, and conversations with God. They provide details concerning the wars, violence and natural disasters in Enoch's day, but also reference the miracles performed by Enoch.

The Book of Moses is itself an excerpt from Joseph Smith's translation of the Bible, which is published in full, complete with these chapters concerning Enoch, by Community of Christ, in the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible, where it appears as part of the Book of Genesis. D&C 104:24 (CofC) / 107:48–49 (LDS) states that Adam ordained Enoch to the higher priesthood (now called the Melchizedek, after the great king and high priest) at age 25, that he was 65 when Adam blessed him, and that he lived for an additional 365 years until he and his city were blessed, making Enoch 430 years old at the time that "he was not, for God took him" (Genesis 5:24).

Additionally in LDS theology, Enoch is implied to be the scribe who recorded Adam's blessings and prophecies at Adam-ondi-Ahman, as recorded in D&C 107:53–57 (LDS) / D&C 104:29b (CofC).

Enoch in Islam[edit]

In Islam, Enoch (Arabic: أَخْنُوخ, romanized: ʼAkhnūkh) is commonly identified with Idris, as for example by the History of Al-Tabari interpretation and the Meadows of Gold.[36] The Quran contains two references to Idris; in Surah Al-Anbiya (The Prophets) verse number 85, and in Surah Maryam (Mary) verses 56–57:

- (The Prophets, 21:85): "And the same blessing was bestowed upon Ismail and Idris and Zul-Kifl, because they all practised fortitude."

- (Mary 19:56–57): "And remember Idris in the Book; he was indeed very truthful, a Prophet. And We lifted him to a lofty station".

Idris is closely linked in Muslim tradition with the origin of writing and other technical arts of civilization,[37] including the study of astronomical phenomena, both of which Enoch is credited with in the Testament of Abraham.[37] Nonetheless, although some Muslims view Enoch and Idris as the same prophet while others do not, many Muslims still honor Enoch as one of the earliest prophets, regardless of which view they hold.[38]

Idris seems to be less mysterious in the Qur'an than Enoch is in the Bible. Furthermore, Idris is the only Antediluvian prophet named in the Qur'an, other than Adam.

Enoch in theosophy[edit]

According to the theosophist Helena Blavatsky, the Jewish Enoch (or the Greek demigod Hermes[39]) was "the first Grand Master and Founder of Masonry."[40]

Asatir[edit]

According to the Asatir, Enoch was buried in Mount Ebal.[41]

Enoch and Enmeduranki[edit]

Enmeduranki was an ancient Sumerian pre-dynastic king who some consider to be a Mesopotamian model for Enoch. Enmeduranki appears as the seventh name on the Sumerian King List, whereas Enoch is the seventh figure on the list of patriarchs in Genesis. Both of them were also said to have been taken up into heaven. Additionally, Sippar, the city of Enmeduranki, is associated with sun worship, while the 365 years that Enoch is stated to have lived may be linked to the number of days in the solar calendar.[42]

Family tree[edit]

- ^ Hebrew: חֲנוֹךְ, Modern: H̱anōḵ, Tiberian: Ḥănōḵ; Greek: Ἑνώχ Henṓkh; Arabic: أَخْنُوخ ʼAkhnūkh, [commonly in Qur'ānic literature]: إِدْرِيس ʼIdrīs

- ^ The use of dative toutois in the Greek text (προεφήτευσεν δὲ καὶ τούτοις instead of the normal genitive with προφητεύω prophēteuō peri auton, "concerning them") has occasioned discussion among commentators including: Ben Witherington,[27] John Twycross,[28] and Cox S.[29]

- ^ a b c Genesis 4:1

- ^ Genesis 4:2

- ^ Genesis 4:25; 5:3

- ^ Genesis 4:17

- ^ Genesis 4:26; 5:6–7

- ^ a b c d Genesis 4:18

- ^ Genesis 5:9–10

- ^ Genesis 5:12–13

- ^ Genesis 5:15–16

- ^ a b Genesis 4:19

- ^ Genesis 5:18–19

- ^ Genesis 4:20

- ^ Genesis 4:21

- ^ a b Genesis 4:22

- ^ Genesis 5:21–22

- ^ Genesis 5:25–26

- ^ Genesis 5:28–30

- ^ a b c Genesis 5:32

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Genesis 5:18–24

- ^ "Enoch the Patriarch". 27 November 2018.

- ^ August Dillmann and R. Charles (1893). The Book of Enoch, translation from Geez.

- ^ 1Enoch, chap. 12

- ^ Luke 3:37, Hebrews 11:5, Jude 1:14–15

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew Concordance - 2596. chanak". Bible Hub.

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew Concordance - 2596. ḥănōḵ". Bible Hub.

- ^ "Conjugation of לַחֲנוֹךְ". Pealim.

- ^ Genesis 5:24, KJV

- ^ Schodde, George H (1882). The Book of Enoch (PDF).

- ^ "MORFILL – The Book of the Secrets of Enoch (1896)" (PDF).

- ^ Eisenman, Robert; Wise, Michael (1992). The Dead Sea Scrolls Uncovered (6 ed.). Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element Books, Inc. p. 95. ISBN 1852303689.

- ^ 5:24 καὶ εὐηρέστησεν Ενωχ τῷ θεῷ καὶ οὐχ ηὑρίσκετο ὅτι μετέθηκεν αὐτὸν ὁ θεός

- ^ LSJ metatithemi

- ^ G3857 παράδεισος Strong's Greek Lexicon. Retrieved 2015-08-01

Strong's Greek 3857_ παράδεισος (paradeisos) – a park, a garden, a paradise Retrieved 2015-08-01 - ^ a b "Jewish Encyclopedia Enoch". Jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2014-03-26.

- ^ Rashi's Commentary on Genesis 5:24. See also Commentary of Ibn Ezra.

- ^ 25:1

- ^ 4Q Enoch (4Q204[4QENAR]) COL I 16–18

- ^ Clontz, T.E. and J., "The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh", Cornerstone Publications, 2008, p. 711, ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5

- ^ "The initial oracle in chapters 1–5 is a paraphrase of part of Deuteronomy 33,24" George W. E. Nickelsburg, The nature and function of revelation 1 Enoch, Jubilees and some Qumranic documents, 1997

- ^ Lars Hartman, Asking for a Meaning: A Study of 1 Enoch 1–5 ConBib NT Series 12 Lund Gleerup, 1979 22–26.

- ^ George WE Nickelsburg & James C Vanderkam, 1 Enoch, Fortress 2001

- ^ R.H. Charles, The Book of Enoch, London SPCK, 1917

- ^ E. Isaac, 1 Enoch, a new Translation and Introduction in Old Testament Pseudepigrapha ed. Charlesworth, Doubleday 1983–85

- ^ Richard Bauckham Jude and the relatives of Jesus in the early church p206 etc.

- ^ Ben Witherington, Letters and Homilies for Jewish Christians: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on Hebrews, James and Jude: "who might be tempted to follow the teachers' example), nonetheless, Jude says that this prophecy refers to these (toutois) false teachers in Jude 14" p624

- ^ John Twycross, The New Testament in the original Greek: with notes by C. Wordsworth His warning is addressed to them as well to those of his own and future ages. p140

- ^ Cox S., Slandering Celestial Beings Hyderabad 2000 "..but instead Jude wrote proepheteusen toutois (verb + dative case pronoun plural) "prophesied TO these men".." p16

- ^ "ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org.

- ^ "ANF02. Fathers of the Second Century: Hermas, Tatian, Athenagoras, Theophilus, and Clement of Alexandria (Entire) - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org.

- ^ "ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org.

- ^ "0150-0215 - Clemens Alexandrinus - Eclogae propheticae - Graecum Text - Lexicum Proprium seu 'Concordance'". www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu.

- ^ "ANF03. Latin Christianity: Its Founder, Tertullian - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org.

- ^ "ANF04. Fathers of the Third Century: Tertullian, Part Fourth; Minucius Felix; Commodian; Origen, Parts First and Second - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org.

- ^ Alexander Philip S. Biblical Figures Outside the Bible p.118 ed. Michael E. Stone, Theodore A. Bergren 2002 p118 "twice in the Qur'an.. was commonly identified by Muslim scholars with the biblical Enoch, and that this identification opened the way for importing into Islam a substantial body of postbiblical Jewish legend about the character and ...."

- ^ a b History of Prophets in Islam and Judaism, B. M. Wheeler, Enoch

- ^ Lives of the Prophets, L. Azzam, S. Academy Publishing

- ^ Helena Blavatsky (June 1, 1885). "Lamas and Druses". Ancient Survivals and Modern Errors. Internet Archive. Bangalore: Theosophy Company (Mysore) Private Ltd. p. 12.

- ^ Helena Blavatsky (1981). "The Eight Wonder by an Unpopular Philosopher (written in 188⁹)". Ancient Science, Doctrine and Beliefs. Internet Archive. Bangalore: Theosophy Company (Mysore) Private LTD. p. 33. (Lucifer, October, 1791)

- ^ The Asatir, Moses Gaster (ed.), The Royal Asiatic Society: London 1927, p. 208

- ^ John Day (2021), From Creation to Abraham: Further Studies in Genesis 1-11. Bloomsbury Publishing. p.106

External links[edit]

- The Descendants of Adam, The Legacy of Cain, The Souls Elijah and Enoch

- Catholic Encyclopedia Henoch (1914)

- Andrei A. Orlov essays on 2 Enoch: Enoch as the Heavenly Priest, Enoch as the Expert in Secrets, Enoch as the Scribe and Enoch as the Mediator

- Ed. Philip P. Wiener Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Cosmic Voyages (1973)

- Dr. Reed C. Durham, Jr. Comparison of Masonic legends of Enoch and Mormon scriptures description of Enoch (1974)

Prophet Idris

Born

Babylon, Iraq[a]

Title Prophet

Predecessor Shith[a]

Successor Nuh[a]

hide

Part of a series on Islam

Islamic prophets

hide

Prophets in the Quran

Listed by Islamic name and Biblical name.ʾĀdam (Adam)

ʾIdrīs (Enoch)

Nūḥ (Noah)

Hūd (Eber)

Ṣāliḥ (Selah)

ʾIbrāhīm (Abraham)

Lūṭ (Lot)

ʾIsmāʿīl (Ishmael)

ʾIsḥāq (Isaac)

Yaʿqūb (Jacob)

Yūsuf (Joseph)

Ayūb (Job)

Shuʿayb (Jethro)

Mūsā (Moses)

Hārūn (Aaron)

Dhu al-Kifl (Ezekiel)

Dāūd (David)

Sulaymān (Solomon)

Yūnus (Jonah)

ʾIlyās (Elijah)

Alyasaʿ (Elisha)

Zakarīya (Zechariah)

Yaḥyā (John)

ʿĪsā (Jesus)

Muḥammad (Muhammad)

show

Main events

show

Views

Islam portal

Islam portalv

t

e

Idris Instructing his Children, Double page from the manuscript of Qisas al-Anbiya by Ishaq ibn Ibrahim al-Nishapuri. Iran (probably Qazvin), 1570-80. Chester Beatty Library

Idris (Arabic: إدريس, romanized: ʾIdrīs) is an ancient prophet mentioned in the Quran, who Muslims believe was the third prophet after Seth.[1][2] He is the second prophet mentioned in the Quran. Islamic tradition has unanimously identified Idris with the biblical Enoch,[3][4] although many Muslim scholars of the classical and medieval periods also held that Idris and Hermes Trismegistus were the same person.[5][6][contradictory]

He is described in the Quran as "trustworthy" and "patient"[7] and the Quran also says that he was "exalted to a high station".[8][9] Because of this and other parallels, traditionally Idris has been identified with the biblical Enoch,[10] and Islamic tradition usually places Idris in the early Generations of Adam, and considers him one of the oldest prophets mentioned in the Quran, placing him between Adam and Noah.[11] Idris' unique status[12] inspired many future traditions and stories surrounding him in Islamic folklore.

According to hadith, narrated by Malik ibn Anas and found in Sahih Muslim, it is said that on Muhammad's Night Journey, he encountered Idris in the fourth heaven.[13] The traditions that have developed around the figure of Idris have given him the scope of a prophet as well as a philosopher and mystic,[14] and many later Muslim mystics, or Sufis, including Ruzbihan Baqli and Ibn Arabi, also mentioned having encountered Idris in their spiritual visions.[15]

Name[edit]

The name Idris (إدريس) has been described as perhaps having the origin of meaning "interpreter."[16] Traditionally, Islam holds the prophet as having functioned an interpretive and mystical role and therefore this meaning garnered a general acceptance. Later Muslim sources, those of the eighth century, began to hold that Idris had two names, "Idris" and "Enoch," and other sources even stated that "Idris' true name is Enoch and that he is called Idris in Arabic because of his devotion to the study of the sacred books of his ancestors Adam and Seth."[17] Therefore, these later sources also highlighted Idris as either meaning "interpreter" or having some meaning close to that of an interpretive role. Several of the classical commentators on the Quran, such as Al-Baizawi, said he was "called Idris from the Arabic dars, meaning "to study," from his knowledge of divine mysteries."[18]

Quran[edit]

Idris is mentioned twice in the Quran, where he is described as a wise man. In surah 19 of the Quran, Maryam, God says:

Also mention in the Book the case of Idris: He was a man of truth (and sincerity), (and) a prophet:

And We raised him to an exalted place.

— Quran 19:56–57 (Yusuf Ali)

Later, in surah 21, al-Anbiya, Idris is again praised:

And (remember) Isma'il, Idris, and Dhu al-Kifl,[19] all (men) of constancy and patience;

We admitted them to Our mercy: for they were of the righteous ones.

— Quran 21:85–86 (Yusuf Ali)

Muslim literature[edit]

According to later Muslim writings, Idris was born in Babylon, a city in present-day Iraq. Before he received the Revelation, he followed the rules revealed to Prophet Seth, the son of Adam. When Idris grew older, God bestowed Prophethood on him. During his lifetime all the people were not yet Muslims. Afterwards, Idris left his hometown of Babylon because a great number of the people committed many sins even after he told them not to do so. Some of his people left with Idris. It was hard for them to leave their home.

They asked Prophet Idris: "If we leave Babylon, where will we find a place like it?" Prophet Idris said: "If we immigrate for the sake of Allah, He will provide for us." So the people went with Prophet Idris and they reached the land of Egypt. They saw the Nile River. Idris stood at its bank and mentioned Allah, the Exalted, by saying: "SubhanAllah."[20]

Islamic literature narrates that Idris was made prophet at around 40, which parallels the age when Muhammad began to prophesy, and lived during a time when people had begun to worship fire.[21] Exegesis embellishes upon the lifetime of Idris, and states that the prophet divided his time into two. For three days of the week, Idris would preach to his people and four days he would devote solely to the worship of God.[21] Many early commentators, such as Tabari,[22] credited Idris with possessing great wisdom and knowledge.

Exegesis narrates that Idris was among "the first men to use the pen as well as being one of the first men to observe the movement of the stars and set out scientific weights and measures."[21] These attributes remain consistent with the identification of Enoch with Idris, as these attributes make it clear that Idris would have most probably lived during the Generations of Adam,[21] the same era during which Enoch lived. Ibn Arabi described Idris as the "prophet of the philosophers" and a number of works were attributed to him.[23] Some scholars wrote commentaries on these supposed works,[24] all while Idris was also credited with several inventions, including the art of making garments.[23]

The commentator Ibn Ishaq narrated that he was the first man to write with a pen and that he was born when Adam still had 308 years of his life to live. In his commentary on the Quranic verses 19:56-57, the commentator Ibn Kathir narrated "During the Night Journey, the Prophet passed by him in fourth heaven. In a hadith, Ibn Abbas asked Ka’b what was meant by the part of the verse which says, ”And We raised him to a high station.” Ka’b explained: Allah revealed to Idris: ‘I would raise for you every day the same amount of the deeds of all Adam’s children’ – perhaps meaning of his time only. So Idris wanted to increase his deeds and devotion. A friend of his from the angels visited and Idris said to him: ‘Allah has revealed to me such and such, so could you please speak to the angel of death, so I could increase my deeds.’ The angel carried him on his wings and went up into the heavens. When they reached the fourth heaven, they met the angel of death who was descending down towards earth. The angel spoke to him about what Idris had spoken to him before. The angel of death said: ‘But where is Idris?’ He replied, ‘He is upon my back.’ The angel of death said: ‘How astonishing! I was sent and told to seize his soul in the fourth heaven. I kept thinking how I could seize it in the fourth heaven when he was on the earth?’ Then he took his soul out of his body, and that is what is meant by the verse: ‘And We raised him to a high station.’[25]

Early accounts of Idris' life attributed "thirty portions of revealed scripture" to him.[18] Therefore, Idris was understood by many early commentators to be both a prophet as well as a messenger. Several modern commentators have linked this sentiment with Biblical apocrypha such as the Book of Enoch and the Second Book of Enoch.[18]

Identification[edit]

Enoch[edit]

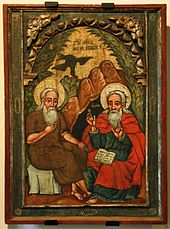

Elijah and Enoch - seventeenth-century icon, Historic Museum in Sanok, Poland

Idris is generally accepted to be the same as Enoch, the patriarch who lived in the Generations of Adam. Many Qur'anic commentators, such as al-Tabari and Qadi Baydawi, identified Idris with Enoch. Baizawi said, "Idris was of the posterity of Seth and a forefather of Noah, and his name was Enoch (Ar. Akhnukh)"[18] Bursalı İsmail Hakkı's commentary on Fuṣūṣ al-Ḥikam by ibn ʿArabi.[26]

Modern scholars, however, do not concur with this identification because they argue that it lacks definitive proof. As translator Abdullah Yusuf Ali says in note 2508 of his translation of the Quran:

Idris is mentioned twice in the Quran, viz., here and in Chapter 21, verse 85, where he is mentioned as among those who patiently persevered. His identification with the Biblical Enoch, may or may not be correct. Nor are we justified in interpreting verse 57 here as meaning the same thing as in Genesis, v.24 ("God took him"), that he was taken up without passing through the portals of death. All we are told is he was a man of truth and sincerity, and a prophet, and that he had a high position among his people.

— Abdullah Yusuf Ali, The Holy Qur'an: Text, Translation and Commentary[27]

With this identification, Idris's father becomes Yarid (يريد), his mother Barkanah, and his wife Aadanah. Idris's son Methuselah would eventually be the grandfather of Nuh (Noah). Hence Idris is identified as the great-grandfather of Noah.[28]

Hermes Trismegistus[edit]

Antoine Faivre, in The Eternal Hermes (1995), has pointed out that Hermes Trismegistus (a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth)[29] has a place in the Islamic tradition, although the name Hermes does not appear in the Quran. Hagiographers and chroniclers of the first centuries of the Islamic Hijrah quickly identified Hermes Trismegistus with Idris,[30] the Prophet of surat 19.56-57 and 21.85, whom the Arabs also identified with Enoch (cf. Genesis 5.18–24). Idris/Hermes was termed "Thrice-Wise" Hermes Trismegistus because he had a threefold origin. The first Hermes, comparable to Thoth, was a "civilizing hero", an initiator into the mysteries of the divine science and wisdom that animate the world; he carved the principles of this sacred science in Egyptian hieroglyphs. The second Hermes, in Babylon, was the initiator of Pythagoras. The third Hermes was the first teacher of alchemy. "A faceless prophet," writes the Islamicist Pierre Lory, "Hermes possesses no concrete or salient characteristics, differing in this regard from most of the major figures of the Bible and the Quran."[31] A common interpretation of the representation of "Trismegistus" as "thrice great" recalls the three characterizations of Idris: as a messenger of god, or a prophet; as a source of wisdom, or hikmet (wisdom from hokhmah); and as a king of the world order, or a "sultanate". These are referred to as müselles bin ni'me.

The star-worshipping sect known as the Sabians of Harran also believed that their doctrine descended from Hermes Trismegistus.[32]

Other identifications[edit]

Due to the linguistic dissimilarities of the name "Idris" with the aforementioned figures, several historians have proposed that this Quranic figure is derived from "Andreas", the immortality-achieving cook from the Syriac Alexander romance.[33][34][35] In addition, historian Patricia Crone proposes that both "Idris" and "Andreas" are derived from the Akkadian epic of Atra-Hasis.[36]

See also[edit]Biblical narratives and the Quran

Legends and the Quran

Muhammad in Islam

Prophets of Islam

Stories of The Prophets

Notes[edit]

^ Jump up to:a b c Assuming Idris is identical with Enoch.

References[edit]

^ Kīsāʾī, Qiṣaṣ, i, 81-5

^ "İDRÎS - TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi". islamansiklopedisi.org.tr. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

^ Erder, Yoram, “Idrīs”, in: Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, General Editor: Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Washington DC.

^ P. S. Alexander, "Jewish tradition in early Islam: The case of Enoch/Idrīs," in G. R. Hawting, J. A. Mojaddedi and A. Samely (eds.), Studies in Islamic and Middle Eastern texts and traditions in memory of Norman Calder ( jss Supp. 12), Oxford 2000, 11-29

^ W.F. Albright, Review of Th. Boylan, The hermes of Egypt, in Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 2 (1922), 190-8

^ H. T. Halman, "Idris," in Holy People of the World: A Cross-Cultural Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2004), p. 388

^ Qur'an 19:56-57 and Qur'an 21:85-86

^ Quran 19:56–57

^ Encyclopedia of Islam, "Idris", Juan Eduardo Campo, Infobase Publishing, 2009, pg. 344

^ Encyclopedia of Islam, Juan Eduardo Campo, Infobase Publishing, 2009, pg. 559

^ Encyclopedia of Islam, Juan Eduardo Campo, Infobase Publishing, 2009, pg. 344: (His translation made him) "Islamic tradition places him sometime between Adam and Noah."

^ Encyclopedia of Islam, Juan Eduardo Campo, Infobase Publishing, 2009, pg. 344: (His translation made him) "a unique human being."

^ Sahih Muslim 162a; 164a

^ Wheeler, Historical Dictionary of the Prophets in Islam and Judaism, Idris, pg. 148

^ Encyclopedia of Islam, Juan Eduardo Campo, Infobase Publishing, 2009, pg. 345"

^ Encyclopedia of Islam, Infobase Publishing, 2009, pg. 344: "It probably originated as a term in ancient Hebrew for "interpreter"..."

^ Encyclopedia of Islam, Juan Eduardo Campo, Infobase Publishing, 2009, pg. 344

^ Jump up to:a b c d A Dictionary of Islam, T.P. Hughes, Ashraf Printing Press, repr. 1989, pg. 192

^ See Ezekiel

^ "Islamic History of the Prophets of God الأنبياء". www.alsunna.org. Archived from the original on 2010-07-08.

^ Jump up to:a b c d Lives of the Prophets, Leila Azzam

^ History of the Prophets and Kings, Tabari, Volume I: Prophets and Patriarchs

^ Jump up to:a b Encyclopedia of Islam, G. Vajda, Idris

^ Ibn Sabi'n is said to have written on one of Idris's works cf. Hajiji Khalifa, iii, 599, no. 7010

^ Tafsir Ibn Kathir; commentary 19:56-57

^ Zaid H. Assfy Islam and Christianity: connections and contrasts, together with the stories of the prophets and imams Sessions, 1977 p122

^ Abdullah Yusuf Ali, The Holy Qur'an: Text, Translation and Commentary C2508. Idris is mentioned twice in the Quran, viz.; here and in 21:85, where he is mentioned among those who patiently persevered. His identification with the Biblical Enoch, who "'walked with God' (Gen. 5:21-24), may or may not be correct. Nor are we justified in interpreting verse 57 here as meaning the same thing as in Gen. 5:24 ("God took him"), that he was taken up without passing through the portals of death. All we are told is that he was a man of truth and sincerity, and a prophet, and that he had a high position among his people. It is this point which brings him in the series of men just mentioned; he kept himself in touch with his people, and was honoured among them. Spiritual progress need not cut us off from our people, for we have to help and guide them. He kept to truth and piety in the highest station.

^ "Hazrat Idrees / Enoch (علیہ السلام) - Biography".

^ A survey of the literary and archaeological evidence for the background of Hermes Trismegistus in the Greek Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth may be found in Bull, Christian H. (2018). The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World: 186. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004370845. ISBN 978-90-04-37084-5. S2CID 165266222. pp. 33–96.

^ Van Bladel, Kevin (2009). The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195376135.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-537613-5. p. 168: "Abu Mas'har’s biography of Hermes, written approximately between 840 and 860, would establish it as common knowledge."

^ (Faivre 1995 pp. 19–20)

^ Stapleton, Henry E.; Azo, R.F.; Hidayat Husain, M. (1927). "Chemistry in Iraq and Persia in the Tenth Century A.D." Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. VIII (6): 317–418. OCLC 706947607. pp. 398–403.

^ Çakmak, Çenap. Islam: A World Encyclopedia, Vol. 1: A-E. 2017. p 674-675.

^ Brown, John Porter. The Darvishes: Or Oriental Spiritualism. Edited by H. A. Rose. 1968. p 174, footnote 3.

^ Brinner, William M. The History of Al-Tabari, Vol. III. Edited by Ehsan Yar-Shater. 1991. p 415, footnote 11.

^ Crone, Patricia. Islam, the Near East, and Varieties of Godlessness: Collected Studies in Three Volumes, Vol. III. Edited by Hanna Siurua. 2016. p 49-70.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ibn Khaldun, Mukkadimma, tr. Rosenthal, i, 229, 240, n. 372; ii, 317, 328, 367ff.; iii, 213

- Ya'kubi, i, 9

- Kissat Idris, c. 1500, MS Paris, Bibl. Nat. Arabic 1947

- Djahiz, Tarbi, ed. Pellat, 26/40

- Sahih Bukhari, Prayer, I, Krehl, i, 99-100; Prophets, 4, Krehl, ii, 335

- A.E. Affifi, Mystical Philosophy of Ibn Arabi, Cambridge, 1939, 21, 110

- Tabari, History of the Prophets and Kings, I: From Creation to Flood, 172-177

- Balami, tr. Zotenberg, i, 95-99

- Tabari, Tafsir Tabari, xvi, 63ff., xvii, 52

- Masudi, Murudj, i, 73

- D. Chwolsson, Die Ssabier und der Sabismus, St. Petersburg, 1856