밀교 (불교)

| 불교 |

|---|

밀교(密敎)는 비밀의 가르침이란 뜻으로 문자 언어로 표현된 현교(顯敎)를 초월한 최고심원(最高深遠)한 가르침을 말한다.[1] 일본에서는 진언종의 구카이(空海)가 불교를 현밀이교(顯密二敎)로 판별하여 금강승, 즉 밀교의 우위를 주장했다.[1]

중국의 불교에서는 밀종(密宗)이라고 한다. 한국과 일본의 불교에서는 진언종이라고도 한다. 밀교는 금강승(金剛乘)이라고도 하는데, "밀교"와 "금강승"이라는 두 낱말은 티베트 불교와 동의어로 사용되는 경우도 있다.

금강승, 즉 밀교는 불법승 삼보 중에서 법의 화신인 대일여래를 본존으로 하는 종파이다. 밀교는 법신불(法身佛)로서의 대비로사나불(大毘盧舍那佛), 즉 대일여래(大日如來)가 부처 자신 및 그 권속(眷屬)을 위하여 비오(秘奧)한 신구의(身口意)의 삼밀(三密)을 풀이한 것으로, 《대일경(大日經)》에서 말하는 태장계(胎藏界), 《금강정경(金剛頂經)》에서 말하는 법문(法門)이나 다라니(陀羅尼) · 인계(印契) · 염송(念誦) · 관정(灌頂) 등의 의궤(儀軌)를 그 내용으로 하고 있다.[1]

금강승, 즉 밀교는 티베트에서 가장 흥하였고, 아직도 티베트의 지배적인 종교 또는 종파이다. 밀교는 힌두교의 영향이 깊게 들어온 불교이다. 티베트 불교에서는 달라이 라마를 관세음보살, 즉 관자재 보살, 혹은 천수천안보살의 화신으로 정교 일치의 지도자로 깊이 존경한다 (참고 판첸 라마). 밀교, 즉 티베트 불교는 중국을 두렵게 할 만큼 호전적이었던 토번, 즉 지금의 티베트인을 가장 평화를 추구하는 민족으로 바꿀 만큼 티베트에 지대한 영향을 미쳤다.

밀교는 중국 원나라 때도 전파되어 오늘날 밀교를 가장 많이 신앙하는 지역은 티베트와 몽골이다.

성립 연대[편집]

연표: 불교 전통의 성립과 발전 (기원전 450년경부터 기원후 1300년경까지) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 450 BCE | 250 BCE | 100 CE | 500 CE | 700 CE | 800 CE | 1200 CE | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| 부파불교 | 대승불교 | 밀교·금강승 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| 상좌부 불교 |

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

| 티베트 불교 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| 천태종 · 정토종 · 일련종 | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| 450 BCE | 250 BCE | 100 CE | 500 CE | 700 CE | 800 CE | 1200 CE | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

밀교의 대두[편집]

인도는 본래 다신교의 나라였다. 불교가 성립되기 이전에 이미 바라문교(婆羅門敎)의 제신(諸神)을 숭배하였으며, 재앙을 막고 복을 받기 위한 요가수행과 성구(聖句)·만트라(眞言)의 구송(口誦), 불 속에 물건을 던져넣으면서 하는 여러 종류의 기원 따위가 행해지고 있었다. 노력에 의하여 정각(正覺)에 이를 것을 이상으로 하는 불타의 가르침은 이들과는 배치되는 것이었으나 꽤 오래전부터 불교 속에 바라문교의 여러 신들이 수호신으로서 받아들여졌고 또 수호주(守護呪) 따위가 독송되고 있었다. 7세기에 들어와서 화엄경(華嚴經) 등 대승불교의 경전을 기반으로 하여 바라문교와 기타 민간종교의 주법(呪法) 등으로부터 영향을 받은 밀교가 성립되었다. 밀교라 함은 다라니나 만트라를 욈으로써 마음을 통일하여 정각에 이르고자 하는 실천적인 가르침이며 그 심오한 경지는 외부에서 들여다보아서는 알 수가 없다는 비밀교라는 뜻의 약칭이다. 여기에는 범신론적인 불타관은 나타나지 않고 만다라(曼茶羅)와, 외우면 영험을 얻게 된다는 다라니(陀羅尼), 식재(息災)·조복(調伏)·증익(增益)을 위한 호마법(護摩法) 등 제법(諸法)의 채용이 그 특색이다.[2]

인도의 밀교[편집]

원시불교에서는 금지되어 있었던 세속적인 주술(呪術)이나 비의(秘儀)가 차차 인도 불교 속에 침투되었는데, 특히 재가신자(在家信者)를 중심으로 해서 일어난 대승불교에는 그 경향이 강하여 대승경전 속에 다라니라고 부르는 주문(呪文)이 있으며 후일 이것이 하나의 독립된 경전이 되었다.[3]

한편, 부처의 법신(法身)의 가르침도 그 범신적(汎神的) 경향으로 신비주의와 연결되기 쉽고, 그 신비주의적 해석 중에는 불교의 궁극적(窮極的)인 입장이 있는 것으로 알려지게 되었다.[3]

이리하여 대승불교의 새로운 전개로서 금강승(金剛乘)이라고 부르는 밀교의 교의가 성립되고, 7세기경 그 교의를 설(說)한 《대일경(大日經)》이나 《금강정경(金剛頂經)》이 출현하였다.[3]

밀교는 부처의 입장에서의 비밀행(秘密行: 삼밀 · 三密)이기 때문에 자기수행이라는 면이 적고, 현실긍정적이라는 면에서 일반인에게 침투하기 쉬워 급속하게 확대되었으나, 현세의 행복추구가 동시에 쾌락추구라고 하는 타락의 위험을 품고 있고, 후에는 남녀의 결합을 신성시하는 좌도밀교(左道密敎)를 낳아 인도 불교 멸망의 한 원인이 되기도 하였다.[3]

잡밀(雜密)·순밀(純密)[편집]

초기의 밀교사상에는 제존(諸尊)도 정리되어 있지 않았으나, 7세기 후반에 들어와서 대일경(大日經)과 금강정경(金剛頂經)이 성립하여 밀교의 이론적 근거가 정비되자 밀교교리의 실천에 의한 성도(成道)가 강조되었다. 이것을 순밀교라 칭하고 그밖의 것을 잡밀이라고 하여 구별한다. 순밀은 금강승(金剛乘)이라고도 한다.[2]

좌도밀교(左道密敎)[편집]

밀교는 바라문교 혹은 힌두교의 지반을 이용하여 퍼지게 되었는데 뒤에는 힌두교의 일파인 시바의 여신 샤크티(性力)를 숭배하는 샤크티파 따위와 결부되어 윤좌예배(輪坐禮拜)와 성적 황홀경 속에서 해탈을 얻으려는 좌도밀교(탄트라 불교)라고 하는 것으로 기울게 되었다. 이것은 인간의 애욕과 쾌락을 긍정하고 즉신성불(卽身成佛)을 가르치려 한 것이었으나 인도의 민중 사이에 잠재해 있었던 성(性) 숭배의 신앙과 겹쳐서 비외(卑猥)스러운 성적비의(性的秘儀)에 떨어지는 수가 많았다.[2]

인도불교의 멸망[편집]

굽타 왕조(270∼470년경)를 중심으로 하여 최성기를 맞았던 대승불교는 뒤이어 고원(高遠)한 학문과 사상체계로 이론화되어 종교로서 민중으로부터 멀어지는 경향이 있었다. 한편 밀교는 민중의 현실적 요구에 부응하는 것이었으나 힌두교적 색채가 강해짐에 따라서 불교 본래의 모습은 희박해지고 다시 좌도화(左道化)되어 타락의 길을 걸음으로써 당시 이슬람 세력에 대항하고 있던 인도 제왕(諸王)의 민족의식과 결부되어 부흥기에 있었던 전통 바라문교-힌두교 앞에서 후퇴를 당하지 않으면 안 될 상황에 있었다. 특히 12세기말부터 13세기초에 걸쳐 배타적 일신주의를 내건 이슬람 세력이 침입하여 불교의 중심지였던 비하르지 방을 점령하고 밀교의 본거지였던 비크라마시라 사원을 비롯하여 많은 불교사원을 파괴하고 많은 승려를 죽였다. 이렇게 하여 불교는 내외적으로 쇠퇴가 촉진되어 인도 땅에서 쇠망하게 되었다. 오늘날 아삼이나 벵골 지방에서 소수의 불교도가 잔존해 있으며 또한 일부에서는 부흥운동도 일어나고 있다.[2]

중국의 밀교[편집]

수당시대(隋唐時代)의 종파 불교에서 마지막을 장식하는 것이 인도 밀교(密敎)의 중국 전래이다.[4]

다라니(陀羅尼)는 예로부터 조금씩 중국으로 전해졌으나 나란다사(寺)의 학승(學僧)이었던 선무외(善無畏)가 716년(당 현종의 開元4)에 입조(入朝)하여 밀교를 전하면서 《대일경(大日經)》과 그 밖의 것을 번역했다.[4] 선무외의 제자인 일행(一行: 683-727)은 삼론(三論)과 천태(天台)를 배워 이 입장에서 《대일경》을 주석하여 《대일경소(大日經疏)》를 저술했다.[4]

또한 720년(당 현종의 開元8)에는 역시 나란다사(寺)의 학승인 금강지(金剛智)가 와서 《금강정염송경(金剛頂念誦經)》을 번역했으며 또한 그의 제자 불공(不空)은 스승의 사망 후 인도에 돌아가 밀교 경전(密敎經典)》을 비롯한 80부의 밀교 경전을 번역했다.[4]

만다라(曼茶羅)의 염송(念誦), 다라니의 독송(讀誦), 가지기도(加持祈禱) 등 독자적인 수법(修法)을 행하는 밀교는 중국으로의 전래 당시부터 당나라 조정과 밀접한 관계를 가져 국가종교적 색채가 짙었으며 후에는 민간에도 유행했다.[4] 당나라 말기에는 무종(武宗)의 폐불(廢佛)로 큰 타격을 받아 민간신앙에 동화했으나 밀교가 지니는 의례나 기도는 중국의 다른 불교 종파에도 큰 영향을 주었다.[4]

한국의 밀교[편집]

한국에 밀교가 처음 들어온 것은 신라의 명랑법사(明朗法師: fl. 668)가 선덕왕 4년(635)에 당나라에서 귀국하면서부터이다.[5] 명랑은 밀교를 신라에 처음 전래하여 진언종의 별파인 신인종(神印宗)의 종조가 되었다.[5][6]

같은 시대의 밀본(密本: fl. 7세기)도 비밀법(秘密法)을 통해 선덕왕의 질병을 치유하여 밀교 전파에 공헌하였다.[5]

명랑과 밀본 이후 혜통(惠通: fl. 7세기)은 당에서 인도 밀교승 선무외(善無畏: 637-735)에게 밀교 교의를 배운 다음 문무왕 5년(665)에 귀국하여 크게 교풍(敎風)을 일으켰으며, 후대에서는 혜통은 해동 진언종(眞言宗)의 조사로 삼았다.[5]

일본의 밀교[편집]

일본의 진언종은 구카이(空海 · くうかい · 홍법 대사: 774-835)가 중국 당나라의 장안으로 건너가 청룡사에서 혜과로부터 배운 밀교를 기반으로 하고 있다.[7]

일본의 진언종은 밀교를 불교의 최고 진리라 천명하고 즉신성불(卽身成佛)의 사상을 강조하였다.[7] 종교의 실천적인 면에서 일본의 진언종은 밀교의 방법을 더욱 중시한다.[7] 또 "국가의 안정을 수호"하며 "재앙을 없애고 복을 쌓는 것"을 경서를 읽고 불사에 종사하는 목적으로 간주하였다.[7]

티베트의 밀교[편집]

밀교는 티베트에서 가장 흥하였고, 지금도 티베트의 지배적인 종교 또는 종파이다. 때문에 "밀교" 또는 "금강승"이라는 두 낱말은 티베트 불교와 동의어로 사용되기도 한다.

주의 사항[편집]

정통 밀교의 참모습을 보지 못하며 밀교에 대해 많은 오해를 가질 수 있어서,[8] 인도 후기 밀교의 경우에는 밀교 수행의 자격은 현교(顯敎)의 경론에 대해 해박한 지식을 갖추고 시험을 거쳐야만 인정되어 밀교 수행에 참여할 수 있다.[9] 티벳 불교의 밀교 수행을 하려면 달라이 라마를 비롯한 현존하는 스승들이 이끄는 관정식(灌頂式)에서 입문 의식을 치러야 한다.[10]

이렇게 관정을 받으면 그것으로 생겨난 영안이 이유가 되어서 아무리 힘들더라도 밀교 수행을 해야 하기 때문에 이를 잘 아는 티베트인들은 오히려 관정을 잘 받으려 하지 않는다.[10] 인도 델리 박물관연구소(NMI)에서 박물관학(Museology)을· 전공한 최연철 박사는 한국 불교인들은 수행을 하지 않더라도 관정을 어떻게든 받고 보자는 풍토가 많다고 평한다.[10]

같이 보기[편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다. |

각주[편집]

- ↑ 가 나 다 종교·철학 > 세계의 종교 > 불 교 > 불교의 분파 > 밀교, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 종교·철학 > 세계의 종교 > 불 교 > 불교의 역사 > 밀교의 대두, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 종교·철학 > 세계의 종교 > 불 교 > 불교의 분파 > 인도불교의 부파와 학파 > 밀교, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 종교·철학 > 세계의 종교 > 불 교 > 불교의 분파 > 중국불교의 종파 > 밀교, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 종교·철학 > 한국의 종교 > 한국의 불교 > 한국불교의 역사 > 삼국시대의 불교 > 밀교의 전래, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

- ↑ 동양사상 > 한국의 사상 > 삼국시대의 사상 > 삼국시대의 불교사상 > 명랑, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 동양사상 > 동양의 사상 > 일본의 사상 > 불교사상 > 진언종, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

- ↑ “티베트 불교 ‘대원만 선정’ 수행의 정수”. 불교닷컴. 2020년 11월 18일.

- ↑ “밀교와 성에 대한 이해”. 불교평론. 2008년 6월 7일.

- ↑ 가 나 다 ““밀교 성적 합일 수행은 극소수의 한 방편일 뿐””. 한겨레 신문. 2009년 6월 3일.

참고 문헌[편집]

이 문서에는 다음커뮤니케이션(현 카카오)에서 GFDL 또는 CC-SA 라이선스로 배포한 글로벌 세계대백과사전의 내용을 기초로 작성된 글이 포함되어 있습니다.

이 문서에는 다음커뮤니케이션(현 카카오)에서 GFDL 또는 CC-SA 라이선스로 배포한 글로벌 세계대백과사전의 내용을 기초로 작성된 글이 포함되어 있습니다.

Vajrayana

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (September 2021) |

| Part of a series on |

| Vajrayana Buddhism |

|---|

|

Vajrayāna (Sanskrit: वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle" ) along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism are names referring to Buddhist traditions associated with Tantra and "Secret Mantra", which developed in the medieval Indian subcontinent and spread to Tibet, East Asia, Mongolia and other Himalayan states.

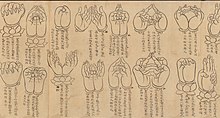

Vajrayāna practices are connected to specific lineages in Buddhism, through the teachings of lineage holders. Others might generally refer to texts as the Buddhist Tantras.[1] It includes practices that make use of mantras, dharanis, mudras, mandalas and the visualization of deities and Buddhas.

Traditional Vajrayāna sources claim that the tantras and the lineage of Vajrayāna was taught by the Buddha Shakyamuni and other figures such as the bodhisattva Vajrapani and Padmasambhava. Contemporary historians of Buddhist studies meanwhile argue that this movement dates to the tantric era of medieval India (c. 5th century CE onwards).[2]

According to Vajrayāna scriptures, the term Vajrayāna refers to one of three vehicles or routes to enlightenment, the other two being the Śrāvakayāna (also known pejoratively as the Hīnayāna) and Mahāyāna (a.k.a Pāramitāyāna).

There are several Buddhist tantric traditions that are currently practiced, including Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Chinese Esoteric Buddhism, Shingon Buddhism and Newar Buddhism.

Terminology[edit]

In Tibetan Buddhism practiced in the Himalayan regions of India, Nepal, and Bhutan, Buddhist Tantra is most often termed Vajrayāna (Tib. རྡོ་རྗེ་ཐེག་པ་, dorje tekpa, Wyl. rdo rje theg pa) and Secret mantra (Skt. Guhyamantra, Tib. གསང་སྔགས་, sang ngak, Wyl. gsang sngags). The vajra is a mythical weapon associated with Indra which was said to be indestructible and unbreakable (like a diamond) and extremely powerful (like thunder). Thus, the term is variously translated as Diamond Vehicle, Thunderbolt Vehicle, Indestructible Vehicle and so on.

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism it is generally known by various terms such as Zhēnyán (Chinese: 真言, literally "true word", referring to mantra), Tángmì or Hanmì (唐密 - 漢密, "Tang Esotericism" or "Han Esotericism"), Mìzōng (密宗, "Esoteric Sect") or Mìjiao (Chinese: 密教; Esoteric Teaching). The Chinese term mì 密 ("secret, esoteric") is a translation of the Sanskrit term Guhya ("secret, hidden, profound, abstruse").[3]

In Japan, Buddhist esotericism is known as Mikkyō (密教, "secret teachings") or by the term Shingon (a Japanese rendering of Zhēnyán), which also refers to a specific school of Shingon-shū (真言宗).

History[edit]

Mahasiddhas and the tantric movement[edit]

Tantric Buddhism is associated with groups of wandering yogis called mahasiddhas in medieval India.[4] According to Robert Thurman, these tantric figures thrived during the latter half of the first millennium CE.[2] According to Reynolds (2007), the mahasiddhas date to the medieval period in North India and used methods that were radically different from those used in Buddhist monasteries, including practicing in charnel grounds.[5]

Since the practice of Tantra focuses on the transformation of poisons into wisdom, the yogic circles came together in tantric feasts, often in sacred sites (pitha) and places (ksetra) which included dancing, singing, consort practices and the ingestion of taboo substances like alcohol, urine, and meat.[6] At least two of the mahasiddhas cited in the Buddhist literature are comparable with the Shaiva Nath saints (Gorakshanath and Matsyendranath) who practiced Hatha Yoga.

According to Schumann, a movement called Sahaja-siddhi developed in the 8th century in Bengal.[7] It was dominated by long-haired, wandering mahasiddhas who openly challenged and ridiculed the Buddhist establishment.[8] The mahasiddhas pursued siddhis, magical powers such as flight and extrasensory perception as well as spiritual liberation.[9]

Ronald M. Davidson states that,

Tantras[edit]

Many of the elements found in Buddhist tantric literature are not wholly new. Earlier Mahāyāna sutras already contained some elements which are emphasized in the Tantras, such as mantras and dharani.[11] The use of protective verses or phrases actually dates back to the Vedic period and can be seen in the early Buddhist texts, where they are termed paritta. The practice of visualization of Buddhas such as Amitābha is also seen in pre-tantric texts like the Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra.[12]

There are other Mahāyāna sutras which contain "proto-tantric" material such as the Gandavyuha and the Dasabhumika which might have served as a central source of visual imagery for Tantric texts.[13] Later Mahāyāna texts like the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra (c. 4th-5th century CE) expound the use of mantras such as Om mani padme hum, associated with vastly powerful beings like Avalokiteshvara. The popular Heart Sutra also includes a mantra.

Vajrayāna Buddhists developed a large corpus of texts called the Buddhist Tantras, some of which can be traced to at least the 7th century CE but might be older. The dating of the tantras is "a difficult, indeed an impossible task" according to David Snellgrove.[14]

Some of the earliest of these texts, Kriya tantras such as the Mañjuśrī-mūla-kalpa (c. 6th century), teach the use of mantras and dharanis for mostly worldly ends including curing illness, controlling the weather and generating wealth.[15] The Tattvasaṃgraha Tantra (Compendium of Principles), classed as a "Yoga tantra", is one of the first Buddhist tantras which focuses on liberation as opposed to worldly goals. In another early tantra, the Vajrasekhara (Vajra Peak), the influential schema of the five Buddha families is developed.[16] Other early tantras include the Mahāvairocana Abhisaṃbodhi and the Guhyasamāja (Gathering of Secrets).[17]

The Guhyasamāja is a Mahayoga class of Tantra, which features forms of ritual practice considered "left-hand" (vamachara) such as the use of taboo substances like alcohol, consort practices, and charnel ground practices which evoke wrathful deities.[18] Ryujun Tajima divides the tantras into those which were "a development of Mahāyānist thought" and those "formed in a rather popular mould toward the end of the eighth century and declining into the esoterism of the left",[19] this "left esoterism" mainly refers to the Yogini tantras and later works associated with wandering yogis. This practice survives in Tibetan Buddhism, but it is rare for this to be done with an actual person. It is more common for a yogi or yogini to use an imagined consort (a buddhist tantric deity, i.e. a yidam).[20]

These later tantras such as the Hevajra Tantra and the Chakrasamvara are classed as "Yogini tantras" and represent the final form of development of Indian Buddhist tantras in the ninth and tenth centuries.[15] The Kalachakra tantra developed in the 10th century.[21] It is farthest removed from the earlier Buddhist traditions, and incorporates concepts of messianism and astrology not present elsewhere in Buddhist literature.[8]

According to Ronald M. Davidson, the rise of Tantric Buddhism was a response to the feudal structure of Indian society in the early medieval period (ca. 500-1200 CE) which saw kings being divinized as manifestations of gods. Likewise, tantric yogis reconfigured their practice through the metaphor of being consecrated (abhiśeka) as the overlord (rājādhirāja) of a mandala palace of divine vassals, an imperial metaphor symbolizing kingly fortresses and their political power.[22]

Relationship to Shaivism[edit]

The question of the origins of early Vajrayāna has been taken up by various scholars. David Seyfort Ruegg has suggested that Buddhist tantra employed various elements of a “pan-Indian religious substrate” which is not specifically Buddhist, Shaiva or Vaishnava.[23]

According to Alexis Sanderson, various classes of Vajrayāna literature developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and Shaivism.[24] The relationship between the two systems can be seen in texts like the Mañjusrimulakalpa, which later came to be classified under Kriya tantra, and states that mantras taught in the Shaiva, Garuda and Vaishnava tantras will be effective if applied by Buddhists since they were all taught originally by Manjushri.[25]

Alexis Sanderson notes that the Vajrayāna Yogini tantras draw extensively from the material also present in Shaiva Bhairava tantras classified as Vidyapitha. Sanderson's comparison of them shows similarity in "ritual procedures, style of observance, deities, mantras, mandalas, ritual dress, Kapalika accouterments like skull bowls, specialized terminology, secret gestures, and secret jargons. There is even direct borrowing of passages from Shaiva texts."[26] Sanderson gives numerous examples such as the Guhyasiddhi of Padmavajra, a work associated with the Guhyasamaja tradition, which prescribes acting as a Shaiva guru and initiating members into Saiva Siddhanta scriptures and mandalas.[27] Sanderson claims that the Samvara tantra texts adopted the pitha list from the Shaiva text Tantrasadbhava, introducing a copying error where a deity was mistaken for a place.[28]

Ronald M. Davidson meanwhile, argues that Sanderson's claims for direct influence from Shaiva Vidyapitha texts are problematic because "the chronology of the Vidyapitha tantras is by no means so well established"[29] and that "the available evidence suggests that received Saiva tantras come into evidence sometime in the ninth to tenth centuries with their affirmation by scholars like Abhinavagupta (c. 1000 c.e.)"[30] Davidson also notes that the list of pithas or sacred places "are certainly not particularly Buddhist, nor are they uniquely Kapalika venues, despite their presence in lists employed by both traditions."[31] Davidson further adds that like the Buddhists, the Shaiva tradition was also involved in the appropriation of Hindu and non-Hindu deities, texts and traditions, an example being "village or tribal divinities like Tumburu".[32]

Davidson adds that Buddhists and Kapalikas as well as other ascetics (possibly Pasupatas) mingled and discussed their paths at various pilgrimage places and that there were conversions between the different groups. Thus he concludes:

Davidson also argues for the influence of non-Brahmanical and outcaste tribal religions and their feminine deities (such as Parnasabari and Janguli).[34]

Traditional legends[edit]

According to several Buddhist tantras as well as traditional Tibetan Buddhist sources, the tantras and the Vajrayana was taught by the Buddha Shakyamuni, but only to some individuals.[35][36] There are several stories and versions of how the tantras were disseminated. The Jñana Tilaka Tantra, for example, has the Buddha state that the tantras will be explained by the bodhisattva Vajrapani.[35] One of the most famous legends is that of king Indrabhuti (also known as King Ja) of Oddiyana (a figure related to Vajrapani, in some cases said to be an emanation of him).[35]

Other accounts attribute the revelation of Buddhist tantras to Padmasambhava, claiming that he was an emanation of Amitaba and Avaloketishvara and that his arrival was predicted by the Buddha. Some accounts also maintain Padmasambhava is a direct reincarnation of Buddha Shakyamuni.[36]

Philosophical background[edit]

According to Louis de La Vallée-Poussin and Alex Wayman, the philosophical view of the Vajrayana is based on Mahayana Buddhist philosophy, mainly the Madhyamaka and Yogacara schools.[39][40] The major difference seen by Vajrayana thinkers is the superiority of Tantric methods, which provide a faster vehicle to liberation and contain many more skillful means (upaya).

The importance of the theory of emptiness is central to the Tantric Buddhist view and practice. The Buddhist emptiness view sees the world as being fluid, without an ontological foundation or inherent existence, but ultimately a fabric of constructions. Because of this, tantric practice such as self-visualization as the deity is seen as being no less real than everyday reality, but a process of transforming reality itself, including the practitioner's identity as the deity. As Stephan Beyer notes, "In a universe where all events dissolve ontologically into Emptiness, the touching of Emptiness in the ritual is the re-creation of the world in actuality".[41]

The doctrine of Buddha-nature, as outlined in the Ratnagotravibhāga of Asanga, was also an important theory which became the basis for Tantric views.[42] As explained by the Tantric commentator Lilavajra, this "intrinsic secret (behind) diverse manifestation" is the utmost secret and aim of Tantra. According to Alex Wayman this "Buddha embryo" (tathāgatagarbha) is a "non-dual, self-originated Wisdom (jnana), an effortless fount of good qualities" that resides in the mindstream but is "obscured by discursive thought."[43] This doctrine is often associated with the idea of the inherent or natural luminosity (Skt: prakṛti-prabhāsvara-citta, T. ’od gsal gyi sems) or purity of the mind (prakrti-parisuddha).

Another fundamental theory of Tantric practice is that of transformation. In Vajrayāna, negative mental factors such as desire, hatred, greed, pride are used as part of the path. As noted by French Indologist Madeleine Biardeau, the tantric doctrine is "an attempt to place kama, desire, in every meaning of the word, in the service of liberation."[44] This view is outlined in the following quote from the Hevajra tantra:

The Hevajra further states that "one knowing the nature of poison may dispel poison with poison."[44] As Snellgrove notes, this idea is already present in Asanga's Mahayana-sutra-alamkara-karika and therefore it is possible that he was aware of Tantric techniques, including sexual yoga.[46]

According to Buddhist Tantra, there is no strict separation of the profane or samsara and the sacred or nirvana, rather they exist in a continuum. All individuals are seen as containing the seed of enlightenment within, which is covered over by defilements. Douglas Duckworth notes that Vajrayana sees Buddhahood not as something outside or an event in the future, but as immanently present.[47]

Indian Tantric Buddhist philosophers such as Buddhaguhya, Vimalamitra, Ratnākaraśānti and Abhayakaragupta continued the tradition of Buddhist philosophy and adapted it to their commentaries on the major Tantras. Abhayakaragupta's Vajravali is a key source in the theory and practice of tantric rituals. After monks such as Vajrabodhi and Śubhakarasiṃha brought Tantra to Tang China (716 to 720), tantric philosophy continued to be developed in Chinese and Japanese by thinkers such as Yi Xing and Kūkai.

Likewise in Tibet, Sakya Pandita (1182-28 - 1251), as well as later thinkers like Longchenpa (1308–1364) expanded on these philosophies in their tantric commentaries and treatises. The status of the tantric view continued to be debated in medieval Tibet. Tibetan Buddhist Rongzom Chokyi Zangpo (1012–1088) held that the views of sutra such as Madhyamaka were inferior to that of tantra, which was based on basic purity of ultimate reality.[48] Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) on the other hand, held that there is no difference between Vajrayāna and other forms of Mahayana in terms of prajnaparamita (perfection of insight) itself, only that Vajrayāna is a method which works faster.[49]

Place within Buddhist tradition[edit]

Various classifications are possible when distinguishing Vajrayāna from the other Buddhist traditions. Vajrayāna can be seen as a third yana, next to Śrāvakayāna and Mahayana.[8] Vajrayāna can be distinguished from the Sutrayana. The Sutrayana is the method of perfecting good qualities, where the Vajrayāna is the method of taking the intended outcome of Buddhahood as the path. Vajrayāna can also be distinguished from the paramitayana. According to this schema, Indian Mahayana revealed two vehicles (yana) or methods for attaining enlightenment: the method of the perfections (Paramitayana) and the method of mantra (Mantrayana).[50]

The Paramitayana consists of the six or ten paramitas, of which the scriptures say that it takes three incalculable aeons to lead one to Buddhahood. The tantra literature, however, claims that the Mantrayana leads one to Buddhahood in a single lifetime.[50] According to the literature, the mantra is an easy path without the difficulties innate to the Paramitayana.[50] Mantrayana is sometimes portrayed as a method for those of inferior abilities.[50] However the practitioner of the mantra still has to adhere to the vows of the Bodhisattva.[50]

Characteristics[edit]

Goal[edit]

The goal of spiritual practice within the Mahayana and Vajrayāna traditions is to become a Sammāsambuddha (fully awakened Buddha), those on this path are termed Bodhisattvas. As with the Mahayana, motivation is a vital component of Vajrayāna practice. The Bodhisattva-path is an integral part of the Vajrayāna, which teaches that all practices are to be undertaken with the motivation to achieve Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings.

In the vehicle of Sutra Mahayana the "path of the cause" is taken, whereby a practitioner starts with his or her potential Buddha-nature and nurtures it to produce the fruit of Buddhahood. In the Vajrayāna the "path of the fruit" is taken whereby the practitioner takes his or her innate Buddha-nature as the means of practice. The premise is that since we innately have an enlightened mind, practicing seeing the world in terms of ultimate truth can help us to attain our full Buddha-nature.[51] Experiencing ultimate truth is said to be the purpose of all the various tantric techniques practiced in the Vajrayana.

Esoteric transmission[edit]

Vajrayāna Buddhism is esoteric in the sense that the transmission of certain teachings only occurs directly from teacher to student during an empowerment (abhiṣeka) and their practice requires initiation in a ritual space containing the mandala of the deity.[52] Many techniques are also commonly said to be secret, but some Vajrayana teachers have responded that secrecy itself is not important and only a side-effect of the reality that the techniques have no validity outside the teacher-student lineage.[citation needed]

The secrecy of teachings was often protected through the use of allusive, indirect, symbolic and metaphorical language (twilight language) which required interpretation and guidance from a teacher.[53] The teachings may also be considered "self-secret", meaning that even if they were to be told directly to a person, that person would not necessarily understand the teachings without proper context. In this way, the teachings are "secret" to the minds of those who are not following the path with more than a simple sense of curiosity.[54][55]

Because of their role in giving access to the practices and guiding the student through them, the role of the Vajracharya Lama is indispensable in Vajrayāna.

Affirmation of the feminine, antinomian and taboo[edit]

Some Vajrayāna rituals traditionally included the use of certain taboo substances, such as blood, semen, alcohol and urine, as ritual offerings and sacraments, though some of these are often replaced with less taboo substances such as yogurt. Tantric feasts and initiations sometimes employed substances like human flesh as noted by Kahha's Yogaratnamala.[56]

The use of these substances is related to the non-dual (advaya) nature of a Buddha's wisdom (buddhajñana). Since the ultimate state is in some sense non-dual, a practitioner can approach that state by "transcending attachment to dual categories such as pure and impure, permitted and forbidden". As the Guhyasamaja Tantra states "the wise man who does not discriminate achieves Buddhahood".[56]

Vajrayāna rituals also include sexual yoga, union with a physical consort as part of advanced practices. Some tantras go further, the Hevajra tantra states ‘You should kill living beings, speak lying words, take what is not given, consort with the women of others’.[56] While some of these statements were taken literally as part of ritual practice, others such as killing were interpreted in a metaphorical sense. In the Hevajra, "killing" is defined as developing concentration by killing the life-breath of discursive thoughts.[57] Likewise, while actual sexual union with a physical consort is practiced, it is also common to use a visualized mental consort.

Alex Wayman points out that the symbolic meaning of tantric sexuality is ultimately rooted in bodhicitta and the bodhisattva's quest for enlightenment is likened to a lover seeking union with the mind of the Buddha.[58] Judith Simmer-Brown notes the importance of the psycho-physical experiences arising in sexual yoga, termed "great bliss" (mahasukha): "Bliss melts the conceptual mind, heightens sensory awareness, and opens the practitioner to the naked experience of the nature of mind."[59] This tantric experience is not the same as ordinary self-gratifying sexual passion since it relies on tantric meditative methods using the illusory body and visualizations as well as the motivation for enlightenment.[60] As the Hevajra tantra says:

Feminine deities and forces are also increasingly prominent in Vajrayāna. In the Yogini tantras in particular, women and female yoginis are given high status as the embodiment of female deities such as the wild and nude Vajrayogini.[62] The Candamaharosana Tantra (viii:29–30) states:

In India, there is evidence to show that women participated in tantric practice alongside men and were also teachers, adepts and authors of tantric texts.[63]

Vows and behaviour[edit]

Practitioners of Vajrayāna need to abide by various tantric vows or pledges called samaya. These are extensions of the rules of the Prātimokṣa and Bodhisattva vows for the lower levels of tantra, and are taken during initiations into the empowerment for a particular Unsurpassed Yoga Tantra. The special tantric vows vary depending on the specific mandala practice for which the initiation is received and also depending on the level of initiation. Ngagpas of the Nyingma school keep a special non-celibate ordination.

A tantric guru, or teacher is expected to keep his or her samaya vows in the same way as his students. Proper conduct is considered especially necessary for a qualified Vajrayana guru. For example, the Ornament for the Essence of Manjushrikirti states:

Tantra techniques[edit]

While all the Vajrayāna Buddhist traditions include all of the traditional practices used in Mahayana Buddhism such as developing bodhicitta, practicing the paramitas, and meditations, they also make use of unique tantric methods and Dzogchen meditation which are seen as more advanced. These include mantras, mandalas, mudras, deity yoga, other visualization based meditations, illusory body yogas like tummo and rituals like the goma fire ritual. Vajrayana teaches that these techniques provide faster path to Buddhahood.[65]

A central feature of tantric practice is the use of mantras, and seed syllables (bijas). Mantras are words, phrases or a collection of syllables used for a variety of meditative, magical and ritual ends. Mantras are usually associated with specific deities or Buddhas, and are seen as their manifestations in sonic form. They are traditionally believed to have spiritual power, which can lead to enlightenment as well as supramundane abilities (siddhis).[66]

According to Indologist Alex Wayman, Buddhist esotericism is centered on what is known as "the three mysteries" or "secrets": the tantric adept affiliates his body, speech, and mind with the body, speech, and mind of a Buddha through mudra, mantras and samadhi respectively.[67] Padmavajra (c 7th century) explains in his Tantrarthavatara Commentary, the secret Body, Speech, and Mind of the Buddhas are:[68]

These elements are brought together in the practice of tantric deity yoga, which involves visualizing the deity's body and mandala, reciting the deity's mantra and gaining insight into the nature of things based on this contemplation. Advanced tantric practices such as deity yoga are taught in the context of an initiation ceremony by tantric gurus or vajracharyas (vajra-masters) to the tantric initiate, who also takes on formal commitments or vows (samaya).[66] In Tibetan Buddhism, advanced practices like deity yoga are usually preceded by or coupled with "preliminary practices" called ngondro, consisting of five to seven accumulation practices and includes prostrations and recitations of the 100 syllable mantra.[69]

Vajrayana is a system of tantric lineages, and thus only those who receive an empowerment or initiation (abhiseka) are allowed to practice the more advanced esoteric methods. In tantric deity yoga, mantras or bijas are used during the ritual evocation of deities which are said to arise out of the uttered and visualized mantric syllables. After the deity's image and mandala has been established, heart mantras are visualized as part of the contemplation in different points of the deity's body.[70]

Deity yoga[edit]

The fundamental practice of Buddhist Tantra is "deity yoga" (devatayoga), meditation on a chosen deity or "cherished divinity" (Skt. Iṣṭa-devatā, Tib. yidam), which involves the recitation of mantras, prayers and visualization of the deity, the associated mandala of the deity's Buddha field, along with consorts and attendant Buddhas and bodhisattvas.[71] According to the Tibetan scholar Tsongkhapa, deity yoga is what separates Tantra from Sutra practice.[72]

In the Unsurpassed Yoga Tantras, the most widespread tantric form in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, this method is divided into two stages, the generation stage (utpatti-krama) and the completion stage (nispanna-krama). In the generation stage, one dissolves one's reality into emptiness and meditates on the deity-mandala, resulting in identification with this divine reality. In the completion stage, the divine image along with the illusory body is applied to the realization of luminous emptiness.

This dissolution into emptiness is then followed by the visualization of the deity and re-emergence of the yogi as the deity. During the process of deity visualization, the deity is to be imaged as not solid or tangible, as "empty yet apparent", with the character of a mirage or a rainbow.[73] This visualization is to be combined with "divine pride", which is "the thought that one is oneself the deity being visualized."[74] Divine pride is different from common pride because it is based on compassion for others and on an understanding of emptiness.[75]

The Tibetologist David Germano outlines two main types of completion practice: a formless and image-less contemplation on the ultimate empty nature of the mind and various yogas that make use of the illusory body to produce energetic sensations of bliss and warmth.[76]

The illusory body yogas systems like the Six Dharmas of Naropa and the Six Yogas of Kalachakra make use of energetic schemas of human psycho-physiology composed of "energy channels" (Skt. nadi, Tib. rtsa), "winds" or currents (Skt. vayu, Tib. rlung), "drops" or charged particles (Skt. bindu, Tib. thig le) and chakras ("wheels"). These subtle energies are seen as "mounts" for consciousness, the physical component of awareness. They are engaged by various means such as pranayama (breath control) to produce blissful experiences that are then applied to the realization of ultimate reality.[77]

Other methods which are associated with the completion stage in Tibetan Buddhism include dream yoga (which relies on lucid dreaming), practices associated with the bardo (the interim state between death and rebirth), transference of consciousness (phowa) and Chöd, in which the yogi ceremonially offers their body to be eaten by tantric deities in a ritual feast.

Other practices[edit]

Another form of Vajrayana practice are certain meditative techniques associated with Mahāmudrā and Dzogchen, often termed "formless practices" or the path of self-liberation. These techniques do not rely on deity visualization per se but on direct pointing-out instruction from a master and are often seen as the most advanced and direct methods.[78]

Another distinctive feature of Tantric Buddhism is its unique and often elaborate rituals. They include pujas (worship rituals), prayer festivals, protection rituals, death rituals, tantric feasts (ganachakra), tantric initiations (abhiseka) and the goma fire ritual (common in East Asian Esotericism).

An important element in some of these rituals (particularly initiations and tantric feasts) seems to have been the practice of ritual sex or sexual yoga (karmamudra, "desire seal", also referred to as "consort observance", vidyavrata, and euphemistically as "puja"), as well as the sacramental ingestion of "power substances" such as the mingled sexual fluids and uterine blood (often performed by licking these substances off the vulva, a practice termed yonipuja).[79]

The practice of ingestion of sexual fluids is mentioned by numerous tantric commentators, sometimes euphemistically referring to the penis as the "vajra" and the vagina as the "lotus". The Cakrasamvara Tantra commentator Kambala, writing about this practice, states:

According to David Gray, these sexual practices probably originated in a non-monastic context, but were later adopted by monastic establishments (such as Nalanda and Vikramashila). He notes that the anxiety of figures like Atisa towards these practices, and the stories of Virūpa and Maitripa being expelled from their monasteries for performing them, shows that supposedly celibate monastics were undertaking these sexual rites.[81]

Because of its adoption by the monastic tradition, the practice of sexual yoga was slowly transformed into one which was either done with an imaginary consort visualized by the yogi instead of an actual person, or reserved to a small group of the "highest" or elite practitioners. Likewise, the drinking of sexual fluids was also reinterpreted by later commentators to refer illusory body anatomy of the perfection stage practices.[82]

Symbols and imagery[edit]

Vajrayāna uses a rich variety of symbols, terms, and images that have multiple meanings according to a complex system of analogical thinking. In Vajrayāna, symbols, and terms are multi-valent, reflecting the microcosm and the macrocosm as in the phrase "As without, so within" (yatha bahyam tatha ’dhyatmam iti) from Abhayakaragupta's Nispannayogavali.[83]

The vajra[edit]

The Sanskrit term "vajra" denoted a thunderbolt like a legendary weapon and divine attribute that was made from an adamantine, or an indestructible substance which could, therefore, pierce and penetrate any obstacle or obfuscation. It is the weapon of choice of Indra, the King of the Devas. As a secondary meaning, "vajra" symbolizes the ultimate nature of things which is described in the tantras as translucent, pure and radiant, but also indestructible and indivisible. It is also symbolic of the power of tantric methods to achieve its goals.[84]

A vajra is also a scepter-like ritual object (Standard Tibetan: རྡོ་རྗེ་ dorje), which has a sphere (and sometimes a gankyil) at its centre, and a variable number of spokes, 3, 5 or 9 at each end (depending on the sadhana), enfolding either end of the rod. The vajra is often traditionally employed in tantric rituals in combination with the bell or ghanta; symbolically, the vajra may represent method as well as great bliss and the bell stands for wisdom, specifically the wisdom realizing emptiness. The union of the two sets of spokes at the center of the wheel is said to symbolize the unity of wisdom (prajña) and compassion (karuna) as well as the sexual union of male and female deities.[85]

Imagery and ritual in deity yoga[edit]

Representations of the deity, such as statues (murti), paintings (thangka), or mandala, are often employed as an aid to visualization, in deity yoga. The use of visual aids, particularly microcosmic/macrocosmic diagrams, known as mandalas, is another unique feature of Buddhist Tantra. Mandalas are symbolic depictions of the sacred space of the awakened Buddhas and Bodhisattvas as well as of the inner workings of the human person.[86] The macrocosmic symbolism of the mandala then, also represents the forces of the human body. The explanatory tantra of the Guhyasamaja tantra, the Vajramala, states: "The body becomes a palace, the hallowed basis of all the Buddhas."[87]

Mandalas are also sacred enclosures, sacred architecture that house and contain the uncontainable essence of a central deity or yidam and their retinue. In the book The World of Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai Lama describes mandalas thus: "This is the celestial mansion, the pure residence of the deity." The Five Tathagatas or 'Five Buddhas', along with the figure of the Adi-Buddha, are central to many Vajrayana mandalas as they represent the "five wisdoms", which are the five primary aspects of primordial wisdom or Buddha-nature.[88]

All ritual in Vajrayana practice can be seen as aiding in this process of visualization and identification. The practitioner can use various hand implements such as a vajra, bell, hand-drum (damaru) or a ritual dagger (phurba), but also ritual hand gestures (mudras) can be made, special chanting techniques can be used, and in elaborate offering rituals or initiations, many more ritual implements and tools are used, each with an elaborate symbolic meaning to create a special environment for practice. Vajrayana has thus become a major inspiration in traditional Tibetan art.

Texts[edit]

There is an extended body of texts associated with Buddhist Tantra, including the "tantras" themselves, tantric commentaries and shastras, sadhanas (liturgical texts), ritual manuals (Chinese: 儀軌; Pinyin: Yíguǐ; Romanji: Giki, ), dharanis, poems or songs (dohas), termas and so on. According to Harunaga Isaacson,

Vajrayāna texts exhibit a wide range of literary characteristics—usually a mix of verse and prose, almost always in a Sanskrit that "transgresses frequently against classical norms of grammar and usage," although also occasionally in various Middle Indic dialects or elegant classical Sanskrit.[90]

In Chinese Mantrayana (Zhenyan), and Japanese Shingon, the most influential esoteric texts are the Mahavairocana Tantra and the Vajraśekhara Sūtra.[91][92]

In Tibetan Buddhism, a large number of tantric works are widely studied and different schools focus on the study and practice of different cycles of texts. According to Geoffrey Samuel,

Dunhuang manuscripts[edit]

The Dunhuang manuscripts also contain Tibetan Tantric manuscripts. Dalton and Schaik (2007, revised) provide an excellent online catalogue listing 350 Tibetan Tantric Manuscripts] from Dunhuang in the Stein Collection of the British Library which is currently fully accessible online in discrete digitized manuscripts.[web 1] With the Wylie transcription of the manuscripts they are to be made discoverable online in the future.[94] These 350 texts are just a small portion of the vast cache of the Dunhuang manuscripts.

Traditions[edit]

Although there is historical evidence for Vajrayāna Buddhism in Southeast Asia and elsewhere (see History of Vajrayāna above), today the Vajrayāna exists primarily in the form of the two major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism and Japanese Esoteric Buddhism in Japan known as Shingon (literally "True Speech", i.e. mantra), with a handful of minor subschools utilising lesser amounts of esoteric or tantric materials.

The distinction between traditions is not always rigid. For example, the tantra sections of the Tibetan Buddhist canon of texts sometimes include material not usually thought of as tantric outside the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, such as the Heart Sutra[95] and even versions of some material found in the Pali Canon.[96][a]

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism[edit]

Esoteric and Tantric teachings followed the same route into northern China as Buddhism itself, arriving via the Silk Road and Southeast Asian Maritime trade routes sometime during the first half of the 7th century, during the Tang dynasty and received sanction from the emperors of the Tang dynasty. During this time, three great masters came from India to China: Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi, and Amoghavajra who translated key texts and founded the Zhenyan (真言, "true word", "mantra") tradition.[97] Zhenyan was also brought to Japan as Shingon during this period. This tradition focused on tantras like the Mahavairocana tantra, and unlike Tibetan Buddhism, it does not employ the antinomian and radical tantrism of the Anuttarayoga Tantras. The prestige of this tradition eventually influenced other schools of Chinese Buddhism such as Chan and Tiantai to adopt various esoteric practices over time, leading to a merging of teachings between the various schools.[98][99][100] During the Yuan dynasty, the Mongol emperors made Tibetan Buddhism the official religion of China, and Tibetan lamas were given patronage at the court.[101] Imperial support of Tibetan Vajrayana continued into the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Today, esoteric traditions are deeply embedded in mainstream Chinese Buddhism and expressed through various rituals which make use of tantric mantra and dhāraṇī and the veneration of certain tantric deities like Cundi and Acala.[102] One example of esoteric teachings still practiced in many Chinese Buddhist monasteries is the Śūraṅgama Sūtra and the dhāraṇī revealed within it, the Śūraṅgama Mantra, which are especially influential in the Chinese Chan tradition.[103]

Another form of esoteric Buddhism in China is Azhaliism, which is practiced among the Bai people of China and venerates Mahakala as a major deity.[104][105]

Japanese Esotericism[edit]

Shingon Buddhism[edit]

The Shingon school is found in Japan and includes practices, known in Japan as Mikkyō ("Esoteric (or Mystery) Teaching"), which are similar in concept to those in Vajrayana Buddhism. The lineage for Shingon Buddhism differs from that of Tibetan Vajrayana, having emerged from India during the 9th-11th centuries in the Pala Dynasty and Central Asia (via China) and is based on earlier versions of the Indian texts than the Tibetan lineage. Shingon shares material with Tibetan Buddhism – such as the esoteric sutras (called Tantras in Tibetan Buddhism) and mandalas – but the actual practices are not related. The primary texts of Shingon Buddhism are the Mahavairocana Sutra and Vajrasekhara Sutra. The founder of Shingon Buddhism was Kukai, a Japanese monk who studied in China in the 9th century during the Tang dynasty and brought back Vajrayana scriptures, techniques and mandalas then popular in China. The school was merged into other schools in China towards the end of the Tang dynasty but was sectarian in Japan. Shingon is one of the few remaining branches of Buddhism in the world that continues to use the siddham script of the Sanskrit language.

Tendai Buddhism[edit]

Although the Tendai school in China and Japan does employ some esoteric practices, these rituals came to be considered of equal importance with the exoteric teachings of the Lotus Sutra. By chanting mantras, maintaining mudras, or practicing certain forms of meditation, Tendai maintains that one is able to understand sense experiences as taught by the Buddha, have faith that one is innately an enlightened being, and that one can attain enlightenment within the current lifetime.

Shugendō[edit]

Shugendō was founded in 7th-century Japan by the ascetic En no Gyōja, based on the Queen's Peacocks Sutra. With its origins in the solitary hijiri back in the 7th century, Shugendō evolved as a sort of amalgamation between Esoteric Buddhism, Shinto and several other religious influences including Taoism. Buddhism and Shinto were amalgamated in the shinbutsu shūgō, and Kūkai's syncretic religion held wide sway up until the end of the Edo period, coexisting with Shinto elements within Shugendō[106]

In 1613 during the Edo period, the Tokugawa Shogunate issued a regulation obliging Shugendō temples to belong to either Shingon or Tendai temples. During the Meiji Restoration, when Shinto was declared an independent state religion separate from Buddhism, Shugendō was banned as a superstition not fit for a new, enlightened Japan. Some Shugendō temples converted themselves into various officially approved Shintō denominations. In modern times, Shugendō is practiced mainly by Tendai and Shingon sects, retaining an influence on modern Japanese religion and culture.[107]

Korean milgyo[edit]

Esoteric Buddhist practices (known as milgyo, 密教) and texts arrived in Korea during the initial introduction of Buddhism to the region in 372 CE.[108] Esoteric Buddhism was supported by the royalty of both Unified Silla (668-935) and Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392).[108] During the Goryeo Dynasty esoteric practices were common within large sects like the Seon school, and the Hwaeom school as well as smaller esoteric sects like the Sinin (mudra) and Ch'ongji (Dharani) schools. During the era of the Mongol occupation (1251-1350s), Tibetan Buddhism also existed in Korea though it never gained a foothold there.[109]

During the Joseon dynasty, Esoteric Buddhist schools were forced to merge with the Son and Kyo schools, becoming the ritual specialists. With the decline of Buddhism in Korea, Esoteric Buddhism mostly died out, save for a few traces in the rituals of the Jogye Order and Taego Order.[109]

There are two Esoteric Buddhist schools in modern Korea: the Chinŏn (眞言) and the Jingak Order (眞 覺). According to Henrik H. Sørensen, "they have absolutely no historical link with the Korean Buddhist tradition per se but are late constructs based in large measures on Japanese Shingon Buddhism."[109]

Indo-Tibetan Buddhism[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

Vajrayāna Buddhism was initially established in Tibet in the 8th century when various figures like Padmasambhāva (8th century CE) and Śāntarakṣita (725–788) were invited by King Trisong Detsen, some time before 767. Tibetan Buddhism reflects the later stages tantric Indian Buddhism of the post-GuptaEarly Medieval period (500 to 1200 CE).[110][111] This tradition practices and studies a set of tantric texts and commentaries associated with the more "left hand," (vamachara) tantras, which are not part of East Asian Esoteric Buddhism. These tantras (sometimes termed 'Anuttarayoga tantras' include many transgressive elements, such as sexual and mortuary symbolism that is not shared by the earlier tantras that are studied in East Asian Buddhism. These texts were translated into Classical Tibetan during the "New translation period" (10th-12th centuries). Tibetan Buddhism also includes numerous native Tibetan developments, such as the tulku system, new sadhana texts, Tibetan scholastic works, Dzogchen literature and Terma literature. There are four major traditions or schools: Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, and Gelug.

In the pre-modern era, Tibetan Buddhism spread outside of Tibet primarily due to the influence of the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), founded by Kublai Khan, which ruled China, Mongolia and eastern Siberia. In the modern era it has spread outside of Asia due to the efforts of the Tibetan diaspora (1959 onwards). The Tibetan Buddhist tradition is today found in Tibet, Bhutan, northern India, Nepal, southwestern and northern China, Mongolia and various constituent republics of Russia that are adjacent to the area, such as Amur Oblast, Buryatia, Chita Oblast, the Tuva Republic and Khabarovsk Krai. Tibetan Buddhism is also the main religion in Kalmykia. It has also spread to Western countries and there are now international networks of Tibetan Buddhist temples and meditation centers in the Western world from all four schools.

Nepalese Newar Buddhism[edit]

Newar Buddhism is practiced by Newars in Nepal. It is the only form of Vajrayana Buddhism in which the scriptures are written in Sanskrit and this tradition has preserved many Vajrayana texts in this language. Its priests do not follow celibacy and are called vajracharya (literally "diamond-thunderbolt carriers").

Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism[edit]

Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism refers to the traditions of Esoteric Buddhism found in the Indonesian islands of Java and Sumatra before the rise and dominance of Islam in the region (13-16th centuries). The Buddhist empire of Srivijaya (650 CE–1377 CE) was a major center of Esoteric Buddhist learning which drew Chinese monks such as Yijing and Indian scholars like Atiśa.[112] The temple complex at Borobudur in central Java, built by the Shailendra dynasty also reflects strong Tantric or at least proto-tantric influences, particularly of the cult of Vairocana.[113][114]

Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism may have also reached the Philippines, possibly establishing the first form of Buddhism in the Philippines. The few Buddhist artifacts that have been found in the islands reflect the iconography of Srivijaya's Vajrayana.[115]

Southern Esoteric Buddhism[edit]

"Southern Esoteric Buddhism" or Borān kammaṭṭhāna ('ancient practices') is a term for esoteric forms of Buddhism from Southeast Asia, where Theravada Buddhism is dominant. The monks of the Sri Lankan, Abhayagiri vihara once practiced forms of tantra which were popular in the island.[116] Another tradition of this type was Ari Buddhism, which was common in Burma. The Tantric Buddhist 'Yogāvacara' tradition was a major Buddhist tradition in Cambodia, Laos and Thailand well into the modern era.[117] This form of Buddhism declined after the rise of Southeast Asian Buddhist modernism.

This form of esoteric Buddhism is unique in that it developed in Southeast Asia and has no direct connection to the Indian Tantric Movement of the Mahasiddhas and the tantric establishments of Nalanda and Vikramashila Universities. Thus, it does not make use of the classic Buddhist tantras and has its own independent literature and practice tradition.

Academic study difficulties[edit]

Serious Vajrayana academic study in the Western world is in early stages due to the following obstacles:[118]

- Although a large number of Tantric scriptures are extant, they have not been formally ordered or systematized.

- Due to the esoteric initiatory nature of the tradition, many practitioners will not divulge information or sources of their information.

- As with many different subjects, it must be studied in context and with a long history spanning many different cultures.

- Ritual, as well as doctrine, need to be investigated.

Buddhist tantric practice is categorized as secret practice; this is to avoid misinformed people from harmfully misusing the practices. A method to keep this secrecy is that tantric initiation is required from a master before any instructions can be received about the actual practice. During the initiation procedure in the highest class of tantra (such as the Kalachakra), students must take the tantric vows which commit them to such secrecy.[web 2] "Explaining general tantra theory in a scholarly manner, not sufficient for practice, is likewise not a root downfall. Nevertheless, it weakens the effectiveness of our tantric practice."[web 3]

Terminology[edit]

The terminology associated with Vajrayana Buddhism can be confusing. Most of the terms originated in the Sanskrit language of tantric Indian Buddhism and may have passed through other cultures, notably those of Japan and Tibet, before translation for the modern reader. Further complications arise as seemingly equivalent terms can have subtle variations in use and meaning according to context, the time and place of use. A third problem is that the Vajrayana texts employ the tantric tradition of twilight language, a means of instruction that is deliberately coded. These obscure teaching methods relying on symbolism as well as synonym, metaphor and word association add to the difficulties faced by those attempting to understand Vajrayana Buddhism:

The term Tantric Buddhism was not one originally used by those who practiced it. As scholar Isabelle Onians explains:

See also[edit]

- Malaysian Vajrayana

- Buddhism in Bhutan

- Buddhism in the Maldives

- Buddhism in Nepal

- Buddhism in Russia

- Kashmir Shaivism

- Category:Tibetan Buddhist spiritual teachers

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Macmillan Publishing 2004, pp. 875–876.

- ^ a b David B. Gray, ed. (2007). The Cakrasamvara Tantra: The Discourse of Śrī Heruka (Śrīherukābhidhāna). Thomas F. Yarnall. American Institute of Buddhist Studies at Columbia University. pp. ix–x. ISBN 978-0-9753734-6-0.

- ^ Jianfu Lü (2017). Chinese and Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism. pp. 72–82 . Studies on East Asian Religions, Volume: 1. Brill.

- ^ Ray, Reginald A.; Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism, 2000

- ^ Reynolds, John Myrdhin. "The Mahasiddha Tradition in Tibet". Vajranatha. Vajranatha. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 168.

- ^ Schumann 1974, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Kitagawa 2002, p. 80.

- ^ Dowman, The Eighty-four Mahasiddhas and the Path of Tantra - Introduction to Masters of Mahamudra, 1984.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M.,(2002). Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, Columbia University Press, p. 228, 234.

- ^ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. p 122.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 225.

- ^ Osto, Douglas. “Proto–Tantric” Elements in The Gandavyuha sutra. Journal of Religious History Vol. 33, No. 2, June 2009.

- ^ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 147.

- ^ a b Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 205-206.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 210.

- ^ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan Esotericism, Routledge, (2008), page 19.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 212.

- ^ Tajima, R. Étude sur le Mahàvairocana-Sùtra

- ^ Mullin, Glenn H.; Tsong-Kha-Pa, (2005) The Six Yogas Of Naropa, Tsongkhapa's Commentary Entitled A Book Of Three Inspirations A Treatise On The Stages Of Training In The Profound Path Of Naro's Six Dharmas, p. 70. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-234-7

- ^ Schumann 1974.

- ^ Gordon White, David; Review of "Indian Esoteric Buddhism", by Ronald M. Davidson, University of California, Santa Barbara JIATS, no. 1 (October 2005), THL #T1223, 11 pp.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 171.

- ^ Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 124.

- ^ Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 129-131.

- ^ Sanderson, Alexis; Vajrayana:, Origin and Function, 1994

- ^ Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 144-145.

- ^ Huber, Toni (2008). The holy land reborn : pilgrimage & the Tibetan reinvention of Buddhist India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-226-35648-8.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 204.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 206.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 207.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 214.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 217.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 228, 231.

- ^ a b c Verrill, Wayne (2012) The Yogini’s Eye: Comprehensive Introduction to Buddhist Tantra, Chapter 7: Origin of Guhyamantra

- ^ a b Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, The Eight Manifestations of Guru Rinpoche, Translation and transcription of a teaching given in (May 1992),

- ^ Orlina, Roderick (2012). "Epigraphical evidence for the cult of Mahāpratisarā in the Philippines". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 35 (1–2): 165–166. ISSN 0193-600X. Archived from the original on 2019-05-30. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

This image was previously thought to be a distorted Tārā, but was recently correctly identified as a Vajralāsyā (‘Bodhisattva of amorous dance’), one of the four deities associated with providing offerings to the Buddha Vairocana and located in the southeast corner of a Vajradhātumaṇḍala.

- ^ Weinstein, John. "Agusan Gold Vajralasya". Google Arts & Culture. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019.

Scholars think that the statue may represent an offering goddess from a three-dimensional Vajradhatu (Diamond World) mandala.

- ^ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan Esotericism, 2013, page 3.

- ^ L. de la Vallée Poussin, Bouddhisme, études et matériaux, pp. 174-5.

- ^ Beyer, Stephan; The Cult of Tārā: Magic and Ritual in Tibet, 1978, page 69

- ^ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 125.

- ^ Wayman, Alex; Yoga of the Guhyasamajatantra: The arcane lore of forty verses : a Buddhist Tantra commentary, 1977, page 56.

- ^ a b Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 202.

- ^ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 125-126.

- ^ Snellgrove, David. (1987) Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. pp 126.

- ^ Duckworth, Douglas; Tibetan Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna in "A companion to Buddhist philosophy", page 100.

- ^ Koppl, Heidi. Establishing Appearances as Divine. Snow Lion Publications 2008, chapter 4.

- ^ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan Esotericism, 2013, page 5.

- ^ a b c d e Macmillan Publishing 2004, p. 875.

- ^ Palmo, Tenzin (2002). Reflections on a Mountain Lake:Teachings on Practical Buddhism. Snow Lion Publications. pp. 224–5. ISBN 978-1-55939-175-7.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, pages 198, 231.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 198.

- ^ Morreale, Don (1998) The Complete Guide to Buddhist America ISBN 1-57062-270-1 p.215

- ^ Trungpa, Chögyam and Chödzin, Sherab (1992) The Lion's Roar: An Introduction to Tantra ISBN 0-87773-654-5 p. 144.

- ^ a b c Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 236.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 237.

- ^ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan esotericism, page 39.

- ^ Simmer-Brown, Judith; Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism, 2002, page 217

- ^ Simmer-Brown, Judith; Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism, 2002, page 217-219

- ^ Simmer-Brown, Judith; Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism, 2002, page 219

- ^ a b Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, pages 198, 240.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, pages 198, 242.

- ^ Tsongkhapa, Tantric Ethics: An Explanation of the Precepts for Buddhist Vajrayana Practice ISBN 0-86171-290-0, page 46.

- ^ Hopkins, Jeffrey; Tantric Techniques, 2008, pp 220, 251

- ^ a b Gray, David (2007), The Cakrasamvara Tantra (The Discourse of Sri Heruka): Śrīherukābhidhāna: A Study and Annotated Translation (Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences), p. 132.

- ^ Wayman, Alex; Yoga of the Guhyasamajatantra: The arcane lore of forty verses : a Buddhist Tantra commentary, 1977, page 63.

- ^ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan esotericism, page 36.

- ^ Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World, The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Shambala, page 178.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, and Tribe. Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, pp. 223-224.

- ^ Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt; Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra, 2004, p. 37

- ^ Power, John (2007). Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, p. 271.

- ^ Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World, The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Shambala, page 218.

- ^ Cozort, Daniel; Highest Yoga Tantra, page 57.

- ^ Power, John; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, page 273.

- ^ Gray, David (2007), The Cakrasamvara Tantra (The Discourse of Sri Heruka): Śrīherukābhidhāna: A Study and Annotated Translation(Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences), pp. 73-74

- ^ Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt; Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra, 2004, p. 45

- ^ Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World, The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Shambala, page 112-113.

- ^ Gray, David (2007), The Cakrasamvara Tantra (The Discourse of Sri Heruka): Śrīherukābhidhāna: A Study and Annotated Translation (Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences), pp. 108-118.

- ^ Gray, David (2007), The Cakrasamvara Tantra (The Discourse of Sri Heruka): Śrīherukābhidhāna: A Study and Annotated Translation (Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences), p. 118.

- ^ Gray, David (2007), The Cakrasamvara Tantra (The Discourse of Sri Heruka): Śrīherukābhidhāna: A Study and Annotated Translation (Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences), p. 126.

- ^ Gray, David (2007), The Cakrasamvara Tantra (The Discourse of Sri Heruka): Śrīherukābhidhāna: A Study and Annotated Translation (Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences), pp. 121, 127.

- ^ Wayman, Alex; Yoga of the Guhyasamajatantra: The arcane lore of forty verses : a Buddhist Tantra commentary, 1977, page 62.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 217.

- ^ Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 219.

- ^ Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt; Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra, 2004, p. 42

- ^ Wayman, Alex; The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan esotericism, page 83.

- ^ Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World, The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Shambala, page 130.

- ^ Isaacson, Harunaga (1998). Tantric Buddhism in India (from c. 800 to c. 1200). In: Buddhismus in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Band II. Hamburg. pp.23–49. (Internal publication of Hamburg University.) pg 3 PDF

- ^ Isaacson[citation needed]

- ^ Griffin, David Ray (1990), Sacred Interconnections: Postmodern Spirituality, Political Economy, and Art, SUNY Press, p. 199.

- ^ Emmanuel, Steven M. (2015), A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy, John Wiley & Sons, p. 120.

- ^ Samuel, Geoffrey (1993), Civilized shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan societies, Smithsonian Institution Press, p. 226.

- ^ Dalton, Jacob & van Schaik, Sam (2007). Catalogue of the Tibetan Tantric Manuscripts from Dunhuang in the Stein Collection [Online]. Second electronic edition. International Dunhuang Project. Source: [1] (accessed: Tuesday February 2, 2010)

- ^ Conze, The Prajnaparamita Literature

- ^ Peter Skilling, Mahasutras, volume I, 1994, Pali Text Society[2], Lancaster, page xxiv

- ^ Baruah, Bibbhuti (2008) Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism: p. 170

- ^ Orzech, Charles D. (general editor) (2011). Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia, Brill, Page 296.

- ^ Sharf, Robert (2001) Coming to Terms With Chinese Buddhism: A Reading of the Treasure Store Treatise: p. 268

- ^ Faure, Bernard (1997) The Will to Orthodoxy: A Critical Genealogy of Northern Chan Buddhism: p. 85

- ^ Nan Huaijin. Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. York Beach: Samuel Weiser. 1997. p. 99.

- ^ Orzech, Charles D. (1989). "Seeing Chen-Yen Buddhism: Traditional Scholarship and the Vajrayāna in China". History of Religions. 29 (2): 87–114. doi:10.1086/463182. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 1062679. S2CID 162235701.

- ^ Shi, Hsüan Hua (1977). The Shurangama Sutra, pp. 68–71 Sino-American Buddhist Association, Buddhist Text Translation Society. ISBN 978-0-917512-17-9.

- ^ Huang, Zhengliang; Zhang, Xilu (2013). "Research Review of Bai Esoteric Buddhist Azhali Religion Since the 20th Century". Journal of Dali University.

- ^ Wu, Jiang (2011). Enlightenment in Dispute: The Reinvention of Chan Buddhism in Seventeenth-Century China. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199895564. p. 441

- ^ Miyake, Hitoshi. Shugendo in History. pp45–52.

- ^ 密教と修験道 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Georgieva-Russ, Nelly. Esoteric Buddhist Ritual Objects of the Koryŏ Dynasty (936-1392)

- ^ a b c Sørensen. Esoteric Buddhism under the Koryŏ in the Light of the Greater East Asian Tradition. International Journal of Buddhist Thought & Culture September 2006, Vol.7, pp. 55-94.

- ^ White, David Gordon, ed. (2000). Tantra in Practice. Princeton University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-691-05779-6.

- ^ Davidson, Ronald M (2004). Indian Esoteric Buddhism: Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 2. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- ^ J. Takakusu (2005). A Record of the Buddhist Religion : As Practised in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671-695)/I-Tsing. New Delhi, AES. ISBN 81-206-1622-7.

- ^ Levenda, Peter. Tantric Temples: Eros and Magic in Java, page 99.

- ^ Fontein, Jan. Entering the Dharmadhātu: A Study of the <Gandavyūha Reliefs of Borobudur, page 233.

- ^ Laszlo Legeza, "Tantric Elements in Pre-Hispanic Gold Art," Arts of Asia, 1988, 4:129-133.

- ^ Cousins, L.S. (1997), "Aspects of Southern Esoteric Buddhism", in Peter Connolly and Sue Hamilton (eds.), Indian Insights: Buddhism, Brahmanism and Bhakd Papers from the Annual Spalding Symposium on Indian Religions, Luzac Oriental, London: 185-207, 410. ISBN 1-898942-153

- ^ Kate Crosby, Traditional Theravada Meditation and its Modern-Era Suppression Hong Kong: Buddha Dharma Centre of Hong Kong, 2013, ISBN 978-9881682024

- ^ Akira 1993, p. 9.

- ^ Bucknell, Roderick & Stuart-Fox, Martin (1986). The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism. Curzon Press: London. ISBN 0-312-82540-4.

- ^ Isabelle Onians, "Tantric Buddhist Apologetics, or Antinomianism as a Norm," D.Phil. dissertation, Oxford, Trinity Term 2001 pg 8

- Web citations

Sources[edit]

- Akira, Hirakawa (1993), Paul Groner (ed.), History of Indian Buddhism, Translated by Paul Groner, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Banerjee, S. C. (1977), Tantra in Bengal: A Study in Its Origin, Development and Influence, Manohar, ISBN 978-81-85425-63-4

- Buswell, Robert E., ed. (2004), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan Reference USA, ISBN 978-0-02-865910-7

- Datta, Amaresh (2006), The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Volume One (A To Devo), Volume 1, Sahitya Akademi publications, ISBN 978-81-260-1803-1

- Harding, Sarah (1996), Creation and Completion - Essential Points of Tantric Meditation, Boston: Wisdom Publications

- Hawkins, Bradley K. (1999), Buddhism, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-21162-8

- Hua, Hsuan; Heng Chih; Heng Hsien; David Rounds; Ron Epstein; et al. (2003), The Shurangama Sutra - Sutra Text and Supplements with Commentary by the Venerable Master Hsuan Hua, Burlingame, California: Buddhist Text Translation Society, ISBN 978-0-88139-949-3, archived from the original on May 29, 2009

- Kitagawa, Joseph Mitsuo (2002), The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-1762-0

- Macmillan Publishing (2004), Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan Publishing

- Mishra, Baba; Dandasena, P.K. (2011), Settlement and urbanization in ancient Orissa

- Patrul Rinpoche (1994), Brown, Kerry; Sharma, Sima (eds.), kunzang lama'i shelung [The Words of My Perfect Teacher], San Francisco, California, USA: HarperCollinsPublishers, ISBN 978-0-06-066449-7 Translated by the Padmakara Translation Group. With a foreword by the Dalai Lama.

- Ray, Reginald A (2001), Secret of the Vajra World: The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, Boston: Shambhala Publications

- Schumann, Hans Wolfgang (1974), Buddhism: an outline of its teachings and schools, Theosophical Pub. House

- Snelling, John (1987), The Buddhist handbook. A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice, London: Century Paperbacks

- Thompson, John (2014). "Buddhism's Vajrayāna: Meditation". In Leeming, David A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion (2nd ed.). Boston: Springer. pp. 250–255. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6086-2_9251. ISBN 978-1-4614-6087-9.

- Thompson, John (2014). "Buddhism's Vajrayāna: Rituals". In Leeming, David A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion (2nd ed.). Boston: Springer. pp. 255–259. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6086-2_9347. ISBN 978-1-4614-6087-9.

- Thompson, John (2014). "Buddhism's Vajrayāna: Tantra". In Leeming, David A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion (2nd ed.). Boston: Springer. pp. 260–265. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6086-2_9348. ISBN 978-1-4614-6087-9.

- Wardner, A.K. (1999), Indian Buddhism, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Williams, Paul; Tribe, Anthony (2000), Buddhist Thought: A complete introduction to the Indian tradition, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-18593-3

Further reading[edit]

- Rongzom Chözang; Köppl, Heidi I. (trans) (2008). Establishing Appearances as Divine. Snow Lion. pp. 95–108. ISBN 9781559392884.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Thrangu Rinpoche; Harding, Sarah (2002). Creation and Completion: Essential Points of Tantric Meditation. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-312-7.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Barron, Richard (1998). Buddhist Ethics. The Treasury of Knowledge (book 5). Ithaca: Snow Lion. pp. 215–306. ISBN 978-1-55939-191-7.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Guarisco, Elio; McLeod, Ingrid (2004). Systems of Buddhist Tantra:The Indestructible Way of Secret Mantra. The Treasury of Knowledge (book 6 part 4). Ithaca: Snow Lion. ISBN 9781559392105.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Guarisco, Elio; McLeod, Ingrid (2008). The Elements of Tantric Practice:A General Exposition of the Process of Meditation in the Indestructible Way of Secret Mantra. The Treasury of Knowledge (book 8 part 3). Ithaca: Snow Lion. ISBN 9781559393058.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Harding, Sarah (2007). Esoteric Instructions: A Detailed Presentation of the Process of Meditation in Vajrayana. The Treasury of Knowledge (book 8 part 4). Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 978-1-55939-284-6.

- Kongtrul, Jamgon; Barron, Richard (2010). Journey and Goal: An Analysis of the Spiritual Paths and Levels to be Traversed and the Consummate Fruition state. The Treasury of Knowledge (books 9 & 10). Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications. pp. 159–251, 333–451. ISBN 978-1-55939-360-7.

- Tantric Ethics: An Explanation of the Precepts for Buddhist Vajrayana Practice by Tson-Kha-Pa, ISBN 0-86171-290-0

- Perfect Conduct: Ascertaining the Three Vows by Ngari Panchen, Dudjom Rinpoche, ISBN 0-86171-083-5

- Āryadeva's Lamp that Integrates the Practices (Caryāmelāpakapradīpa): The Gradual Path of Vajrayāna Buddhism according to the Esoteric Community Noble Tradition, ed. and trans by Christian K. Wedemeyer (New York: AIBS/Columbia Univ. Press, 2007). ISBN 978-0-9753734-5-3

- S. C. Banerji, Tantra in Bengal: A Study of Its Origin, Development and Influence, Manohar (1977) (2nd ed. 1992). ISBN 8185425639

- Arnold, Edward A. on behalf of Namgyal Monastery Institute of Buddhist Studies, fore. by Robert A. F. Thurman. As Long As Space Endures: Essays on the Kalacakra Tantra in Honor of H.H. the Dalai Lama, Snow Lion Publications, 2009.

- Snellgrove, David L.: Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors. London: Serindia, 1987.

External links[edit]

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Vajrayāna |

Media related to Vajrayana at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vajrayana at Wikimedia Commons- An Introduction to Vajrayana

- What is Vajrayana Buddhism?

밀교

이 기사에는 여러 가지 문제가 있습니다 . |

밀교 는 비밀 [주1] 의 가르침을 의미하는 [2] 대승불교 속의 비밀교 [3] 로, 비밀 불교 의 약칭 [4] . 금강승 , 금강1승교 , 금강승교 라고도 한다 .

의미와 위치 지정 [ 편집 ]

일본 에서는 진언종 의 동 밀과 천대 종 에서 의 대밀 을 가리키지만, 인도 나 티베트 에 있어서의 동종의 불교 사상도 포함해 총칭하는 일도 있다 [6] . 불교학 은 밀교를 '후기 대승'에 포함하지만, 일부는 후기 대승과 밀교를 구별하려는 생각도 있다 [7] [8] .

또, 인도에서의 대승불교에서 밀교로의 전개과정에 관한 연구의 어프로치에 대해, 진언종 의 승려· 불교학자 인 마츠나가 유케이 는 이하의 3개로 정리하고 있다 [9] :

- 대승불교와 밀교를 각각 이질적인 것으로 파악한다. 를 위치시키는 방법(일본의 진언종 등, 후술).

- 대승불교와 밀교를 동일한 기반에서 파악한다 : 용수 와 제파 가 중관사상에서 후기 밀교사상에 도달한 것처럼 철학적 사색의 진전의 귀결로서 밀교가 등장했다고 파악하는 방법(티벳 불교 등)

- 대승불교에서 밀교로의 전개를 철학적인 사색의 진전에 요구하지 않고, 종교 혹은 순수하게 신앙의 영역으로서 처리하는 방법( 샤시브 산 다스구프타 , 인도·서유럽의 불교학자 등).

마츠나가는 이 중 세 번째 잡는 방법을 가장 타당하게 하면서도 '밀교' 속에 인도 중기밀교가 거의 포함되지 않고 논의가 진행되고 있다는 것을 지적하고 있다.

진언종에서는 현교 와 대비되는 곳의 가르침으로 여겨진다 [10] . 인도 불교의 현교와 밀교를 계승한 티베트 불교 에 있어서도, 대승을 현교와 진언 밀교로 나누는 형태로 현밀의 가르침이 설해지고 있다. 밀교의 다른 용어로는 금강승 (vajrayāna, 바쥬라야나), 진언승 (mantrayāna, 만트라야나) 등으로도 불린다.

- 금강승이라는 용어

금강이라는 말은 이미 부파불교 시대의 경론에서 보이고 [11] , 부파불전의 논장 ( 아비다르마 )의 시대부터, 보리수 하에 있어서의 석가의(강마)성도는, 금강(보물) 자리로 이루어져 묘사가 보이지만 [12] [13] , 금강승의 단어가 출현하는 것은 밀교 경전에서이다 [14] . 금강승 의 말은, 금강정경 계통의 인도밀교를, 성문승 ·대승과 대비하여, 제3의 최고의 가르침으로 보는 입장으로부터의 명칭이지만, 대일경 계통도 포함한 밀교의 총칭으로서 사용되는 경우도 있고 [15] 서구에서도 문헌 중에 불교 용어로 등장한다.

- 영어 번역

영어에서는 구미의 학자에 의해 밀교(비밀불교)에 자주 Esoterism의 번역어가 들어간다. Esoterism으로 여겨지는 이유로는 크게 두 가지 해석이 주어지고 있다. 첫째, 밀교는 입문 의례(관정)를 통과한 유자격자 이외에 나타나지 않는 가르침인 것, 둘째는 언어로 표현할 수 없는 부처님의 깨달음을 설한 것이기 때문이라고 하는 것을 들 수 있다 [16] .

개요 [ 편집 ]

밀교는 「아자관」으로 대표되는 시각적인 명상을 중시하고 만다라 나 법구류, 관정 의 의식을 수반하는 「인신」이나 「삼아야형」등의 상징적 인 가르침을 취지로 하여 그것을 받 다른 사람에게는 나타내서는 안되는 비밀의 가르침으로 여겨진다 [주 2] .

공해 (홍법대사)는 밀교가 현교 와 다른 점을 ' 판현밀이교론 ' 중 '밀교의 삼원칙'으로 다음과 같이 꼽고 있다.

밀교는 남녀노소를 불문하고 금세(이세)에 있어서의 성불인 「즉신성불」을 설교하고, 「전법 관정」의 의식을 가지고 「자병(샤비오)와 같은」[주 3] 와 스승이 제자에게 대비하여 교리를 완전히 상속한 것을 증명하고, 받는 사람에게 아리 (교사)의 칭호와 자격을 준다. 인도 밀교를 계승한 티베트 밀교가 한때 '라마교'라고 칭한 것은 티베트 밀교에서는 사자 상승에 있어서의 개별의 전승인 혈맥을 중첩해, 자신의 「근본 라마」( 사승 )에 대해서 헌신적 에 귀의 한다는 특징을 파악한 것이다.

인도 밀교 [ 편집 ]

부파 불교 [ 편집 ]