Follow the Author

Lilia Tarawa

Daughter of Gloriavale: My life in a Religious Cult by Lilia Tarawa (Author)

Format: Kindle Edition

4.4 out of 5 stars 382 ratings

====

9 hours and 10 minutes

Switch between reading the Kindle book & listening to the Audible narration with Whispersync for Voice.

Get the Audible audiobook for the reduced price of $4.49 after you buy the Kindle book.

-------------------------

In this personal account, Lilia Tarawa exposes the shocking secrets of the cult, with its rigid rules and oppressive control of women. She describes her fear when her family questioned Gloriavale's beliefs and practices.

When her parents fled with their children, Lilia was forced to make a desperate choice: to stay or to leave. No matter what she chose, she would lose people she loved.

In the outside world, Lilia struggled. Would she be damned to hell for leaving? How would she learn to navigate this strange place called 'the world'? And would she ever find out the truth about the criminal convictions against her grandfather?

'A powerful and revealing book...' Kirsty Wynn, New Zealand Herald

'An affecting parable and testament, in the most commendably secular senses.' David Hill, New Zealand Listener

--

320 pages

23 August 2017

Product description

Review

"A powerful and revealing book." --New Zealand Herald

"An affecting parable and testament, in the most commendably secular senses." --New Zealand Listener --This text refers to an alternate kindle_edition edition.

About the Author

Lilia is a health and lifestyle business mentor who lives in Christchurch. --This text refers to the paperback edition.

Customer Reviews:

4.4 out of 5 stars 382 ratings

Lilia Tarawa

Lilia Te Aroha Māia Tarawa is a bestselling New Zealand writer, keynote speaker and educator on self-care, liberation and empowerment.

She is a member of the Māori Ngāi Tahu tribe.

Lilia was born in New Zealand's infamous religious cult, Gloriavale, and broke free with her eleven family members at eighteen years of age.

Her extraordinary life experience compelled her to a career promoting human rights and welfare.

The author's written works address human rights topics - free choice, religious oppression, and well-being.

Visit the author's websites:

www.liliatarawa.com

www.facebook.com/liliatarawa

www.instagram.com/liliatarawa

-----

Top reviews

Gena Drinnan

5.0 out of 5 stars Highly recommend!!Reviewed in Australia 🇦🇺 on 22 May 2020

Verified Purchase

I read this book in just three days and could not put it down. If you're interested in inspiration, sociology, psychology and kick ass women standing their ground and evolving into their highest selves then this is the book for you!

A beautifully honest, raw and authentic book written by Lilia. The way she writes makes you feel as though you know her. She has an amazing way of respectfully honouring herself and her loved ones in this book.

It’s almost unbelievable to think that there are cults out there that can get away with what they do and heavily influence and manipulate the lives of such beautiful people. Lilia is a WARRIOR and I love seeing her journey unfold.

Highly, highly recommend reading!

HelpfulReport abuse![]()

Laura Broadway

5.0 out of 5 stars Fantastic!!Reviewed in Australia 🇦🇺 on 17 April 2021

Verified Purchase

I Literally couldn’t put it down, beautiful and sensitively written insight into the Gloriavale community! Highly recommend, loved it so much i finished it in 3 days!!

HelpfulReport abuse![]()

Amazon Customer

5.0 out of 5 stars Compelling ready, a journey to healingReviewed in Australia 🇦🇺 on 30 September 2017

Verified Purchase

Excellent book which gave a very good insight into mind control of cults. It was nice to follow the author's path of healing and to be given the story of both sides of the fence in a more factual rather than emotive manner.

2 people found this helpful

suze

5.0 out of 5 stars InspiringReviewed in Australia 🇦🇺 on 24 November 2017

Verified Purchase

This journey from repression and total domination to being free and responsible for your own life is exceptional - as is your immediate family who are very brave. Thanks Lilia, for sharing your journey.

-----

Translate all reviews to English![]()

Mum to girlies

5.0 out of 5 stars Fascinating readReviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 25 February 2019

Verified Purchase

Really interesting and chilling read. Could not put it down!

One person found this helpfulReport abuse![]()

Genevieve lutton

4.0 out of 5 stars Well writtenReviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 26 March 2021

Verified Purchase

Well written heart wrenching story of a one brave girls journey out of a religious cult

One person found this helpfulReport abuse![]()

Leanne

5.0 out of 5 stars An unforgettable readReviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 19 September 2018

Verified Purchase

The journey that this woman has had, and the hurdles that she has overcome are spectacular. The fact that she has managed to surpass the hurdles that her upbringing set for her is unbelievable.

2 people found this helpfulReport abuse![]()

nicola carroll

5.0 out of 5 stars A great readReviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 4 January 2019

Verified Purchase

Fascinating

One person found this helpfulReport abuse![]()

Sitty

5.0 out of 5 stars A wonderful autobiography!Reviewed in Germany 🇩🇪 on 9 September 2019

Verified Purchase

Lilia Tarawa writes captivating and emotionally about her life in Gloriavale. I could barely put the book out of my hand!

It describes very appropriately the conflict that one experiences when one tries to question views that were otherwise regarded as uncontroversial truth. Unbelievable is how she describes her time after the cult in which she first has to learn and understand that one can question worldviews at all.

It's hard to summarize right after reading how she sees her former life in Gloriavale, but she writes of memories full of joy and love but also the worst moments of her life so far.

So I can only recommend reading it myself...

The conclusion she draws is beautiful... “Transformation and healing don't happen overnight. They take baby steps and a sound of love and heaps of honest self-exploration. You have to be willing to get uncomfortable, stay open-minded and speak up for what you believe in. It's the best rebellion.”

Translated from German by Amazon

See original ·Report translation

=====

Goodreads

=====

Daughter of Gloriavale: My Life in a Religious Cult

Lilia Tarawa

4.03

1,368 ratings149 reviews

In this personal account, Lilia Tarawa exposes the shocking secrets of the cult, with its rigid rules and oppressive control of women. She describes her fear when her family questioned Gloriavale's beliefs and practices.

When her parents fled with their children, Lilia was forced to make a desperate choice: to stay or to leave. No matter what she chose, she would lose people she loved.

In the outside world, Lilia struggled. Would she be damned to hell for leaving? How would she learn to navigate this strange place called 'the world'? And would she ever find out the truth about the criminal convictions against her grandfather?

261 pages, Kindle Edition

Published August 23, 2017

Lilia Tarawa is a New Zealand Māori #1 best-selling author and transformational speaker whose personal story has inspired millions of people around the world to speak their truth and claim their power.

Her #1 best-selling memoir Daughter of Gloriavale: My Life in a Religious Cult, was written in 4 months, part-time around her day job.

Her TEDxTalk, 'I grew up in a cult. It was heaven—and hell.' rocketed to over eight-and-a-half million views on YouTube, achieved 2018 Top Five most-viewed TEDxTalks in the Worldand is transcribed into six different languages on TED.com

The 5’44 curly-haired brunette passionately tells inspiring stories to anyone with listening ears and to her surprise, she’s managed to get quite a crowd to listen, including the Guardian, Life Matters, TVNZ 1 SUNDAY, Listener Magazine, Radio NZ

and many more.

She is a an artsy, bookish type who lives in Ōtautahi/Christchurch.

============

Mauzi

213 reviews

8 followers

Follow

August 26, 2017

I liked this a lot more than I thought I would - it didn't feel sensationalist at all, and I thought she did a fantastic job of depicting her life in Gloriavale. It was an intriguing insight into the community, and overall, it's a book about overcoming difficulties, rather than something written for shock value (which, I'll admit, is what I was expecting going into it).

rumour-has-it

16 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Andrea.

Andrea

378 reviews

53 followers

Follow

September 2, 2017

A gem of a book. Lilia writes with deep honesty, exposing herself to the world with great courage. She describes vividly the metamorphosis from servitude and fearful self-doubt, to freedom and self-love. The pain of breaking the physical, emotional and mental chains must have been enormous. I certainly could not have had the strength to do what she did and not shatter.

I hope your story gives strength and hope to others who are striving for freedom of any kind.

Te Aroha Maia indeed Lilia. You deserve much happiness and peace and love.

11 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Jessica Gillies.

Jessica Gillies

197 reviews

34 followers

Follow

September 3, 2017

I admire Lilia for having the courage to speak out about her experiences at Gloriavale , both positive and negative- as well as their real consequences as she left and adjusted to life outside the community. This book certainly both inspired and challenged me.

favorites

memoirs-and-biographies

new-zealand

8 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Melody Schwarting.

Melody Schwarting

1,391 reviews

82 followers

Follow

August 13, 2021

Taking the Lord's name in vain is a little bit less about OMG and a whole lot more about using God's name to justify one's own desires.

Tarawa grew up in the Gloriavale cult of New Zealand, living in a commune with her and many other large families where they labored without receiving wages* and held everything in common. Gloriavale was founded by Tarawa's grandfather, Neville Cooper, an Australian evangelist, who later called himself Hopeful Christian. He briefly served time for sexual abuse charges, but that never affected his standing in the cult, because they interpreted it as religious persecution.

Tarawa clearly explains why the cult grew so large, and why her family stayed in it for so long. Deep community bonds formed even with harshly punitive systems keeping everyone in line. Families grew large, children were joyfully welcomed, everyone knew his or her place in the community, and individual futures seemed secure when all the rules were followed.

Tarawa always struggled with the rules; the last third of the memoir details how she handled living outside Gloriavale restrictions. There seems to be no concept of eternal security in Gloriavale, so every action was weighted with salvation or damnation, and its effect on a creative child like Tarawa is chillingly detailed. As a Christian myself, it was excruciating to read how the cult leveraged literalist misinterpretations of the KJV to manipulate its members. Tarawa eventually left the faith altogether, though she did attend church after leaving Gloriavale. However, it was a Scripture verse that eventually gave her the courage to agree to leaving with her parents. Colossians 2:8 convinced her that Gloriavale was built more on the whims of her grandfather and less on Scriptural principles, which is completely true. (The Bruderhof comes to mind as a network of similar intentional communities, with better principles and opportunities for their members, and less of a separatist mindset.)

There's a portion where Tarawa discusses how Gloriavale tried to erase her Māori heritage, and notes the aggressions Māori members like herself experienced. Opposed to the Christian vision they were supposedly living toward (Revelation 7:9, 21:24), this tells much more about Neville Cooper's anti-indigenous streak, and the racist leanings of a prominent member from the American South, than what is truly Christian. This, alongside the cult's treatment of women, was the most disturbing to me: using the name of God to create abusive systems that directly contradict the vision of the Christian Scriptures.

I recommend Daughter of Gloriavale to anyone interested in Gloriavale or Christian-affiliated, extreme patriarchalist cults. To those looking for an ex-community memoir, Tarawa's is refreshing in that she still longs for her friends and the community she had at Gloriavale, rather than bashing it and its members completely. It's kind of like the Marie Kondo of ex-cult memoirs: thank you for the good things you gave me, cult, now get out of my house.

Content warnings: discussions of physical and sexual abuse of children (not suffered by the narrator)

*Because they don't receive wages, Gloriavale families qualify as low-income and receive government assistance, which goes into Gloriavale's coffers.

r-2021

r-nf-memoir-essay

5 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Fiona Mackie.

Fiona Mackie

593 reviews

34 followers

Follow

September 7, 2017

Enjoyed reading this as it is such a contrast to the very saccharine tv documentaries that have aired in New Zealand. I admire Lilia's determination to dismantle the indoctrination she received, and to make a life for herself, outside the strictures and restrictions that she had absorbed growing up in Gloriavale.

I think a family tree or list of people mentioned and their relationship to Lilia would have been very useful though, as the families are very big and keeping track of how people were related required a bit of effort!

1point10

adult

biography-autobio-memoir

...more

5 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for chooksandbooksnz.

chooksandbooksnz

150 reviews

12 followers

Follow

July 21, 2021

Daughter of Gloriavale - Lilia Tarawa

Gloriavale is a closed Christian community based in the isolated Haupiri Valley on the rugged West Coast Of New Zealand. To this very day, the Gloriavale community is still going and according to google has up to 500 members.

Lilia is the granddaughter of Neville Cooper (a.k.a Hopeful Christian) who established Gloriavale and is the cult leader. Gloriavale is only a few hours drive from where I live and it is not unusual to see ‘Cooperites’ in town. They are not hard to spot as Cooperites are only ever permitted to wear the distinctive, modest, blue uniform.

Cooperites are taught solid values. They are extremely hard working, community driven and 110% dedicated to their faith. These are some of the wonderful values Gloriavale is built on.

Unfortunately there is also an extremely ugly side too. The power and control held by leaders is scary. The level of brainwashing has members unreasonably terrified of the consequences of sinning. Bear in mind a sin in Gloriavale could be anything from disobeying leaders to chewing gum or listening to music.

Lilia is of Māori descent. Her birthright is not something that was accepted in Gloriavale and the leaders basically stripped her of her identity. The leaders denied diversity and believed everyone was all one race with one set of beliefs.

Every role is strongly gendered. As a woman your value lies in domestic duties, serving your husband, baring children and not being heard.

In the last half of the book Lilia talks about her families decision to leave Gloriavale. Leaving behind family, friends and everything you have ever known was bittersweet. It’s hard to appreciate how difficult it must have been coming into a whole new world, creating a new belief system and unlearning everything you were previously taught about life in general. Lilia’s life after Gloriavale could not be more different to her time in the community.

Over the years the cult has been no stranger to controversy and being in the media. Lilia’s extremely personal account of Gloriavale added a lot of detail to all of the above.

This book is extremely difficult to do justice in such a short review as it covers so much. Lilia’s journey is one that will shock you. An incredible read by an inspiring and brave wāhine.

5/5 ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

4 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Cynthia.

Cynthia

273 reviews

9 followers

Follow

May 15, 2019

Another intense story of a young woman (and her family, in this case) escaping the bondage of a "Christian" cult, in New Zealand.

I saw Lilia Tarawa's TEDX presentation and was impressed with her poise and ability to explain about the conflict she felt between the beauty of the Gloriavale locale and her idyllic childhood experiences with a loving extended family, and the oppression she felt and observed as she grew up into an adolescent.

The book had what I consider a good pace, and was well planned and set up. There were no lengthy rehashes of situations, and the history and daily workings of Gloriavale were very interesting. As with Tara in "Education" (about a young woman whose parents were fundamentalist Mormon), Lilia was a bright, sensitive young woman who noticed increasingly the impacts of power and control of the all-male leadership upon the followers of the Church, and more significantly, upon herself. Access to the outside world through the Internet and a renegade cousin were highly influential in her developing understanding of what she wanted her life to be like.

auto-biography

history

religiousabuse

...more

4 likes

1 comment

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Smokerjoerabbit Tong.

Smokerjoerabbit Tong

62 reviews

8 followers

Follow

December 4, 2017

Everyone in New Zealand should read this book....Lilia writes with honesty and clarity about the confines of the religious cult of Gloriavale on the West Coast of NZ. I think many Kiwis can say after watching the TV documentaries also, this particular cult has been of huge interest to the public in general. I loved her writing style and that she has gone on to live a successful life despite what she's been through. Highly recommend

4 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Miz.

Miz

1,343 reviews

37 followers

Follow

October 18, 2019

I enjoyed this book as a bit of voyeuristic 'not in my back yard' type of read.

It's so strange to think that there is this extreme pocket of conservative religious sect on the West Coast. The abuse is awful and I like how the author didn't shy away from that, but also focused on the good parts.

I did find the writing very simple and stilted at the beginning of the novel. When recalling the community and her life at Gloriavale, the story just didn't flow as well as in later chapters. I realise it might be because she was recalling times from childhood but for me there was a big change after she left and was able to reflect. The latter part of the book was better written but felt almost rushed... And I know that most people would read this book for the cult part, it still felt like it needed a good edit to flow a bit better.

But ultimately this is a book about triumph, about female power, and about not letting your past dictate your true path. I couldn't help but feel a bit of pride for Lilia and I hope our paths cross one day so I can tell her how inspirational she is.

non-fiction

3 likes

===

Melinda

969 reviews

11 followers

Follow

June 19, 2022

Contains A+ cult quote: “Thank god for the chance to gawk at yummy church boys on the weekends because I still had a crush on Willing Steadfast.”

3 likes

====

My life in a religious cult: 'The most dangerous place in the world is the womb of an ungodly woman'

After her childhood in a secretive cult founded by her grandfather, New Zealand woman Lilia Tarawa risked hellfire and damnation to escape. In this book extract, she shares a slice of her life at Gloriavale Christian Community

Lilia Tarawa

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/aug/30/my-life-in-a-religious-cult-the-most-dangerous-place-in-the-world-is-the-womb-of-an-ungodly-woman

302

---------

On the west coast of the South Island of New Zealand, a religious cult named Gloriavale Christian Community closed itself off from the rest of the world in 1969.

Founded by the self-styled and self-named Australian religious leader Hopeful Christian – who was convicted and jailed on three charges of indecent sexual assault of a young woman in 1995 – the 500-strong community was run according to a strict and oppressive interpretation of fundamental Christianity.

Women had to cover their heads, show no flesh so as not to tempt sin from the menfolk, do all the domestic work, submit to their husbands and birth as many babies as they could.

Eight years ago, Lilia Tarawa – granddaughter of Hopeful Christian – escaped with her family into what she had always believed to be the evil, wicked world. This is an extract from her memoir about her life in the cult.

“Take out your Bibles.”

Every day began with a Bible reading.

I lifted my desk lid and removed the thick King James Bible that had been issued to me. It was an old book that had been rebound in the community print shop. I stroked the dull-red cover and held the book to my nose. I loved the musty smell of the pages.

Inside the bizarre 1960s cult, The Family: LSD, yoga and UFOs

Read more

“We’re reading from Hebrews 13:17,” Peter pointed to the boy closest to him. “Nathan, read one verse and then you others continue around the room.”

Pages rustled for a brief moment before Nathan began in a clear voice. “Obey them that have the rule over you, and submit yourselves ... ”

The boy beside Nathan picked up the next verse. After each of us had read aloud, Peter finished the chapter. For the rest of class we were taught that to sacrifice one’s self-will and serve the church was the only way to salvation. There was a godly order established in the church – the highest power was God and then Church leaders. Husbands were to submit to the church and wives must submit to their husbands. Children came last and were expected to obey their parents who served the Lord.

“The leaders watch for our souls. If you are obedient to the church you will live long on the Earth and the Lord will bless you,” Peter told us.

He began to pray for our salvation and we clasped our hands and bowed our heads. He thanked God for the wonderful place the leaders had built for us and prayed that we would be saved from the lusts of the world.

We had two more classes after that and I was impatient for them to finish. Today was Friday, PE day, and I couldn’t wait to be out on the field, kicking a soccer ball around.

Peter dismissed us and we tore down to the field, with Jubilant messing around as always and making us laugh at his jokes.

Gloriavale didn’t allow competitive games because it was cause for people to be lifted up in pride. We had to play soccer without keeping score, which I thought was stupid because the whole point of sport was to win. The long dresses were so frustrating to run in but I tackled the football off Jubilant anyway. I didn’t care if my dress flung up, there was no way I was going to let our team lose.

I couldn’t see how beating a child because you felt angry and full of rage was a demonstration of God’s love

Our teacher for the session was Nathaniel Constant so I knew to be careful not to make him angry because his fuse was extremely short. Grace and I called him “Nathaniel Constantly Annoying” behind his back. We kept our distance from his aggressive temper. It didn’t deter Jubilant though. He kept on with the jokes, kicking the ball to the wrong player – anything for a laugh.

Nathaniel yelled at him, then he yelled again. Jubilant cooled it for about five minutes but it wasn’t in his nature to behave even though Nathaniel’s anger was building.

It only took one more smart remark before his temper erupted. “Get out! Leave! Now! Get up to the main building. Go!”

Jubilant grumbled and left the field, but not without throwing a last snide comment. Nathaniel tore after him, caught up and kicked him, then bashed him across the head.

The game halted and the class watched, stunned into silence as Nathaniel kicked our classmate again and then again. He forced him to walk and kept smashing him across the head and kicking him for the entire 30 or so metres to the main building. Jubilant was sobbing and trying to protect himself as he stumbled up the road.

Even though the church taught that it was godly for disobedient children to be beaten, this was so wrong. I was only 11 years old but as I stood there, helpless and watching, my hands to my throat, I knew with every fibre of my being that this was wrong. It was the most shocking thing I’d ever witnessed.

I couldn’t keep playing and neither could the other kids. We were numb from the shock of what had happened. All of us left the soccer field and returned to the classroom. I couldn’t concentrate and after school I found Grace and fumed in disbelief about what had happened.

That evening I poured it all out to Mum. She was furious, both at what Nathaniel had done but also because she couldn’t do anything about it. She was a woman and had little power to intervene in the men’s realm. Both of us waited to see what punishment the men would give Nathaniel. Nothing happened and he continued teaching us. I was disgusted.

The incident fanned my loathing for Gloriavale’s stance on child discipline into a raging furnace. The leaders called it godly, but I thought it was abuse. I couldn’t see how beating a child because you felt angry and full of rage was a demonstration of God’s love.

Some leaders not only encouraged violent beatings but scolded parents who were lenient. This was a church that preached non-violence and was anti-war, yet it saw fit to punish their young for minor errors. The leaders defended their philosophy based on the scripture “spare the rod and spoil the child”. Some men took this literally, using weapons like polystyrene pipe to beat their sons. Certain other members rebelled against the impositions and refused to treat their children badly, and I witnessed loving relationships between many parents and their children.

A wife would, in strict confidence, show me her young children, who had horrific marks on their legs, bottoms and backs where her husband had beaten them. Rage boiled in my chest when I saw those poor children suffering. I vowed to unleash the fury of hell if any husband of mine ever laid a finger on a child of ours in malice.

One quiet morning I was in the high school with my head down studying, as were my 30 other classmates. I was having trouble with a difficult maths problem and bit my lip in deep concentration.

Suddenly a loud noise jolted me out of focus. We looked up from our books, all of us startled. It was Shepherd Fervent bursting into the room.

Fervent was dragging his son Willing by the collar of his shirt and he yanked him to stand before the class. I cringed.

“Children look here!” Fervent commanded.

Bile rose in my throat and I turned away from the appalling scene. How dare a leader treat a child this way?

We didn’t want to look. Willing’s eyes were puffy and red. He’d been crying and he hung his head to the floor.

Fervent puffed out his chest and threw back his shoulders. His balding head caught the light from the window and he smoothed down the sides of his oily hair. “The Bible says, ‘Children, obey your parents in the Lord’,” he shouted. His other hand held a limp leather strap. “Proverbs says, ‘Withhold not correction from the child: for if thou beatest him with the rod, he shall not die’.”

I couldn’t stop looking at the strap because it made me sick to the stomach. Fervent was going to make an example of Willing?

How could he do that to a boy of 13?

“What do you have to say, son?” Fervent poked his son.

Willing stared at the ground and mumbled an apology for being disobedient to his father. I felt a sliver of hope. Maybe the apology was enough to clear him?

Fervent spat a lecture of how godly parents beat their children to submission.

Then he turned to his son.

I screwed my eyes shut, thinking Fervent was going to strap Willing’s hand, but my stomach dropped with horror at his next words.

“Pull down your pants. Bend over.”

In that moment I wanted nothing more than to kill Fervent. To my eyes he was scum of the earth. Willing looked shocked, but obeyed his father.

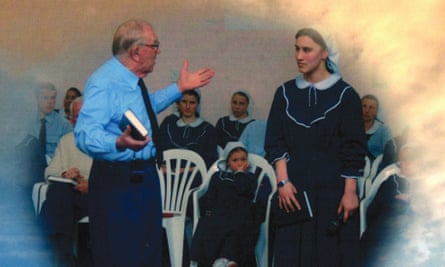

Lilia Tarawa, aged 16, with her grandfather Hopeful Christian at her Commitment ceremony at Gloriavale Christian Community

Lilia Tarawa, aged 16, with her grandfather Hopeful Christian at her Commitment ceremony at Gloriavale Christian CommunityFervent took a wide stance and drew the strap back over his head. Without warning the belt flashed down and bit into Willing’s flesh. He moaned and whimpered with pain. Fervent didn’t stop. With all his strength he whipped the poor boy again, and again, and again.

Bile rose in my throat and I turned away from the appalling scene. Fervent was a pig and no man of God. My knuckles turned white and I gripped the desk in fury. How dare that man – a leader – treat a child this way?

I shut my eyes to block out the horror and covered my ears. I couldn’t watch even though I knew I risked punishment for showing disagreement. The whole time I prayed, “Please God, let it stop. Please make it stop.”

I stared at the pencil groove on the edge of my desk, and my eyes burned with unshed tears. Fervent left his humiliated son standing at the front of the room. The room was deathly silent. When the overseeing teacher gave him a curt nod, Willing stumbled to his desk and buried his sobs in his hands. The class ended and I stumbled to the lockers in a daze.

From that moment I had nothing but love and compassion for Willing. I was popular and loved at school because I was a gifted student of high-status birth so I did my best to include him in my social circles.

An exclusive group of us would meet in the evenings to play basketball or soccer. We were the misfits and the ones who thought outside the box. Willing hung out with us and I developed something of a crush on him which I dared not tell anyone for fear of punishment.

The rules, though, didn’t change my feelings. What I believed was that all children deserved love.

Babies were a big part of life in Gloriavale. Birth control and abortion were strictly forbidden and we were proud of how we didn’t murder children in the womb like so many people in the world.

Grandad was very fond of bragging that we had the biggest families in New Zealand. He liked to show visitors a photo he’d taken of all the children who were number three or more in birth order, saying, “None of these children would be here if their parents practised birth control and didn’t have a faith in God.”

Lilia Tarawa after she left the religious cult

Lilia Tarawa after she left the religious cultA favourite sermon of his was to preach about how lucky we were to have been conceived by Christian parents. He’d say, “Guess where the most dangerous place in the world is? It’s not on the road in cars. It’s not flying through the air in planes. It’s in the womb of an ungodly woman.”

My grandmother bore 16 children to Grandad Hopeful before her death and I grew up surrounded by cousins’ babies. Grandad Hopeful would say, “Children are an inheritance of the Lord. The fruit of the womb is His reward.”

Mum taught me to knit all sorts of babywear – cardigans, booties, hats; I always knitted a matching set for each of Aunt Patie’s babies. Some of the women could knit a whole garment in just a few hours.

Childbirth was highly celebrated and parents were expected to prepare their children for the practicalities of having a large family. Boys and girls aged 10 and older would often attend their mother’s births to assist and learn about the procedure.

We birthed our children at home. There was no need to visit a medical institution for something that was a purely natural part of life. God had promised us that women who continued in holiness and faith would be saved in childbearing. But if there were problems with a birth then a birthing mother would be taken to Greymouth hospital.

The district midwife made regular visits to pregnant women and attended the births to ensure nothing went wrong.

The first baby I ever saw born was my Aunt Patie’s second son when I was 10. When he came out he had the umbilical cord wrapped round his neck, he was blue and wasn’t breathing. He was fine once the midwife got him breathing. Afterwards she asked me if I was OK, but to me this was normal because I’d never seen a baby born before, so I was blissfully unaware of how severe the situation was.

I was there to observe and help with my mother’s next four births: Asher, Judah, Serena and Melodie. Because I was now the oldest girl I learned all the child-rearing skills too. I bathed my younger siblings, changed nappies, helped with potty training and when the babies cried in the night I would climb out of bed to attend to them to relieve my exhausted mother. I watched the women help each other breastfeed, if one mother had an abundance of milk she would suckle the child whose mother didn’t have a good supply.

Women were allowed about two weeks off after giving birth but then they were straight back into the workforce. I always wondered how some of the ladies did it. They would birth during the night and the next morning be at the meal table to present the child to the community. The husband would make a big announcement: “The Lord has blessed us with a new baby boy and his name is Courageous.” Everyone would clap and cheer.

When Patie had her fourth child, complications arose after she’d gone into labour. Her waters had broken, she was fully dilated but the baby wasn’t coming. I was rubbing her back, giving her sips of juice and bathing her face with a cool cloth. The midwife decided she needed urgent medical help but we were so far away from any hospital with no time to wait for an ambulance. We would have to transport Patie ourselves.

The boys brought round one of the stripped-out vans, threw down a mattress, blankets and pillows and we helped Patie lie down. I sat by her head and held her hands as her body was being wracked by gigantic contractions. About 20 minutes into the journey we went over a sharp bump. Patie groaned and gasped out, “Something’s moved. I can feel the baby coming. Right now!”

I shouted, “Stop the van!”

Patie was clenching my hand, almost breaking it. I ignored the pain of it and repeated over and over, “It’s OK. Just breathe through it. Go with the pain.”

She was bearing down. The back doors of the van flung open, I scrambled out, the midwife climbed in and a few minutes later my tiny, screaming cousin Submissive was born. The midwife handed her to me after her mother had a cuddle. I cradled her squawking body in my arms. “Welcome, little girl. You’re going to be so loved.”

----

This is an edited extract from Daughter of Gloriavale: My life in a religious cult by Lilia Tarawa (Allen & Unwin)

===

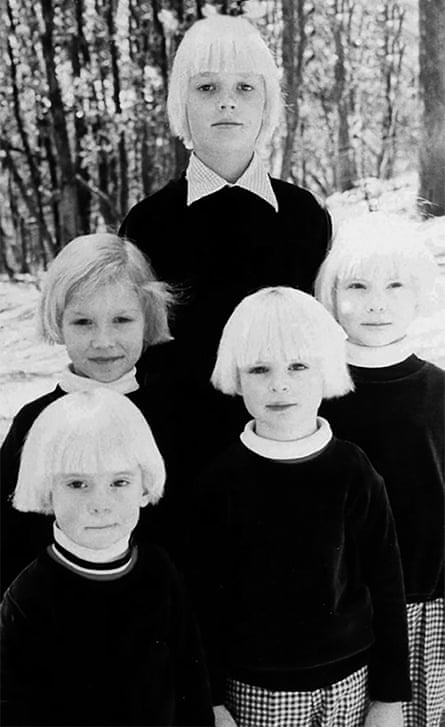

‘There are people out there who probably have a lot to answer for’: five boys with bleached-blond hair who believed they were Anne and Bill Hamilton-Byrne’s children. Photograph: Label Distribution

‘There are people out there who probably have a lot to answer for’: five boys with bleached-blond hair who believed they were Anne and Bill Hamilton-Byrne’s children. Photograph: Label Distribution Anne Hamilton Byrne, her husband William (left) and a friend arrive at Melbourne’s county court in November 1993. Photograph: John Woudstra/The Age

Anne Hamilton Byrne, her husband William (left) and a friend arrive at Melbourne’s county court in November 1993. Photograph: John Woudstra/The Age

Hough in Elgg, Switzerland in 1991 while she was living with the Family. Photograph: Courtesy of the author

Hough in Elgg, Switzerland in 1991 while she was living with the Family. Photograph: Courtesy of the author Hough aged about five, in Chile. Photograph: Courtesy of the author

Hough aged about five, in Chile. Photograph: Courtesy of the author