Buddhist Mandala Illustration: How Art Therapy Captured Spirituality

June 14, 2018 by Lulu Flitton

Lulu Flitton

I am an Integrative counsellor/Psychotherapist (Registered member of the BACP) MBACP (Accre) and Psychologist specialising in family and child Psychology.

Mandala is a Sanskrit word meaning ‘circle’ or centre. The religious and spiritual links of the mandala symbol originate from Buddhism and Hinduism. It is also seen in Jainism.

During the twentieth century, there seems to have been a sense of alienation experienced by Western individuals. Existential philosophies such as modern art, literature, and science, depicted man in search of a higher spiritual core and meaning to life. This burning desire lead the mid-to-late twentieth century individual to delve into spiritual ideas around which they could build a purposeful and meaningful life.

These feelings of isolation and division were thought to be caused by an ego-illusion, which were to be destroyed. Carl Jung was one of the initial Western practitioners to advocate the use of mandalas to achieve this destruction. When used as a therapeutic tool, a mandala is thought to support psychological healing and integration through the unification of opposites, especially when a mandala is created by a client. Also perceived as reflecting the universal inheritance of human kind, mandalas were regarded as archetypal symbols by Jung.

The presence of mandalas has been identified in Western cultures and European art work. For instance, Christianity has a strong connection to mandalas, as has Gnosticism and early Navarro and Pueblo cultures. Esoteric traditions such as alchemy and shamanism also make use of mandalas. Nevertheless, their origin stems from Eastern traditions of Buddhism and Hinduism.

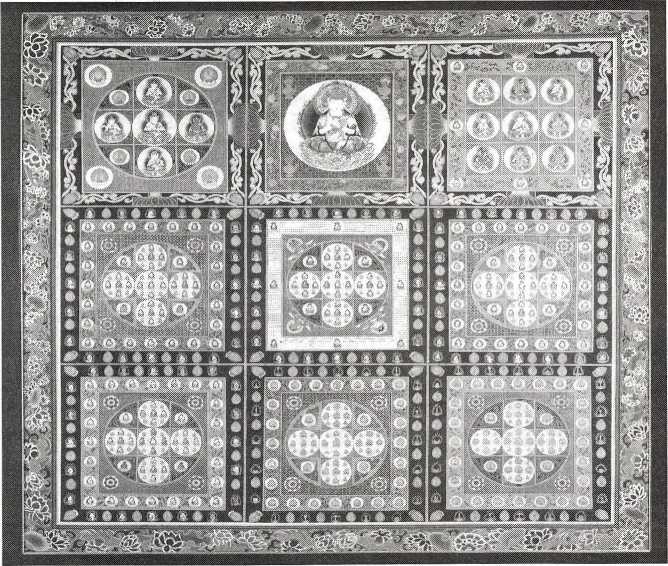

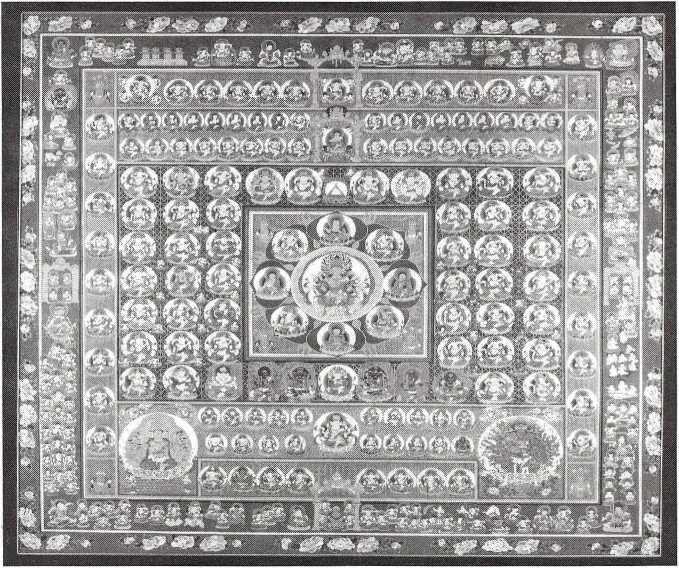

An underlying concept in Tibetan Buddhism involves a belief in the impermanent characteristic of everything, including humans. The Tibetan tradition emphasises this momentary aspect of life through the creation of mandalas. These are made of different coloured sand which are then swept away, highlighting this aspect of fleetingness. Indeed, Tantric Buddhism, which is mainly linked to Tibetan Buddhism, places great emphasis on ritual and symbolism, especially that of the mandala.

Various symbolic associations are represented by mandalas. Mostly, mandalas have links to a sacred palace. When connected as such, a palace lies at the centre of the mandala. The palace has four gates which face the four quarters of the world and is situated within various layers of circles that form a protective barrier around it. Each layer represents a quality such as kindness or compassion, with every surrounding circle following a specific symbolic structure. At the centre of the mandala lies the deity, with whom the mandala is identified. It is the power of this religious figure that the mandala is thought to be invested with.

The use of mandalas as a psychotherapeutic tool was first used by Carl Jung as an expression of a person’s unconscious. Being greatly influenced by Eastern traditions, Jung delved into Tibetan Buddhist symbols. The circular shape of mandalas and their focus on a central point helps towards the integration of otherwise disorganised elements of the psyche, so Jung concluded. Indeed, he frequently observed the presence of mandalas in the dreams and paintings of clients.

- Jung viewed mandalas as symbols to draw, model, act out, or even describe to identify unconscious mechanisms at play that may be affecting the central wholeness of an individual.

- Jung used this art form to enable him to understand ideas he was developing in his thinking concerning the human psyche.

- Providing a grounding centre, mandalas may be used to ‘contain’ a person’s emotions; a way through which an individual is able to settle disorganised feelings.

- A change in an individual’s psychic state is represented in their mandala illustrations.

- Jung considered mandala symbolism as representing a deeper, indescribable, mystical process in which the psyche works to heal and defend itself.

- His awareness of the symbolism of mandalas as psychic concepts led him to argue for the vital existence of psycho-spiritual archetypes.

Since then, mandalas have been widely acknowledged as effective tools in art therapy. They are also used as a form of diagnosis and treatment method for emotional and psychological difficulties.

‘A mandala is the psychological expression of the totality of the Self’.

Jung was one of the first psychoanalysts to view art as a valuable way for people to communicate both their conscious and unconscious desires, feelings, and thoughts. In line with his belief in mandalas as expressing the self in relation to the universal whole and as a representation of a person’s attempt towards achieving ‘individuation’, that is the course by which a person’s consciousness becomes unique to them, Jung placed great emphasis on the search for meaning as a fundamental human need and specifically emphasised notions around the involvement of religion, and concepts of the soul. Indeed, Jung further argued for the benefits in creating these circular symbols as a reflection of a person’s unique existential position and role.

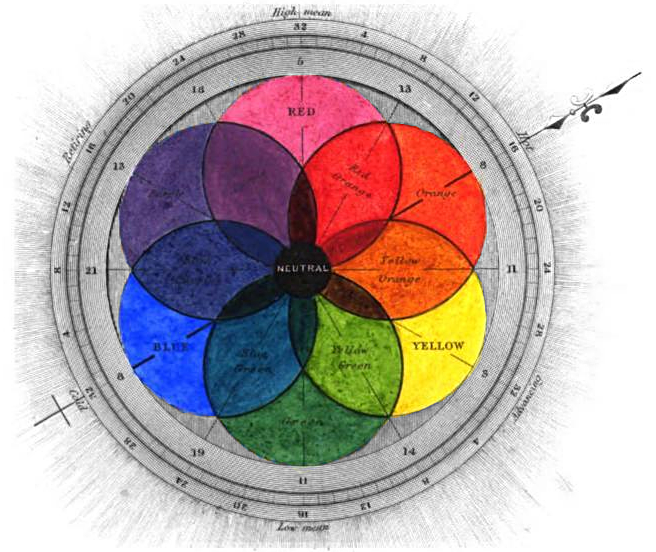

RYB Color Chart from George Field’s 1841 Chromatography; or A treatise on colours and pigments: and of their powers in painting Source

RYB Color Chart from George Field’s 1841 Chromatography; or A treatise on colours and pigments: and of their powers in painting SourceJung also considered the value and meaning of imagination. Not only did he analyse the form of mandalas drawn or represented by clients, Jung also explored their use of colour. When applied to mandalas, chosen colours used by the illustrator have specific meanings. Believing that chosen colours picked by each person reflected a deeper meaning about their personality, Jung therefore encouraged his clients to use colour. Although colours our very personal, each one of them represents specific symbolic meanings. Each colour also has both positive and negative elements to it.

By colouring the mandalas, people enter a deep state of engagement leading to self-discovery. The continual use and analysis of mandala creation and colouring can show change and progress throughout the therapeutic process. Jung observed that when used in such a way, it was advisable to date each mandala to identify specific changes experienced by each illustrator.

When people are unsure about their progress achieved during therapy, a further analysis of each mandala is likely to help them identify progress. This may be done by analysing the outer edge of the design or its centre piece, as well as the use of different colours, which may have changed. For instance, each piece denotes special meanings depending on the shape of the mandala, or the inclusion of particular symbols. Humans have always star gazed for guidance. A star is filled with meanings related to the self, the world, and the cosmos as a whole. The use of a star signifies navigation, intuition, and light–representing confident in an ability to stand alone and be more independent. The use of brighter colours may also denote this development. The use of mandala illustrating is not confined to psychotherapeutic spaces and can be used by anyone wanting to explore and promote their artistic potential.

Tibetan Buddhism has powerful connections to mandala symbolism of a sacred and mystical nature. Greatly inspired by Tibetan Buddhism, Carl Jung regarded mandalas as a depiction of a person’s unconscious and was the first psychoanalysis to advocate the use of mandalas as meaningful psychological tools. Originating from this view, the mandala has become a very beneficial symbol used in art therapy and Jungian depth therapy. Aiming to acquire a meaningful life, and following on from existential traditions, the creation of such circular symbol was according to Jung, a way through which individuals place themselves in accordance to their environment.

References

- Case, Caroline. The Handbook of Art Therapy, Hove: Routledge. 2014

- Henderson, Patti; Rosen, David; and Mascaro, Nathan. ‘Empirical Study on the Healing Nature of Mandalas’. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 2007

- Hogan, Susan. Art Therapy Theories: A Critical Introduction. Oxon: Routledge. 2016

- Jaffe, A. ‘Symbolism in the visual arts’. In C.G. Jung, Man and His Symbols (pp. 255– 322). New York: Dell. 1964

- Jung, Carl. Gustav. Modern Man in Search of a Soul (W. S. Dell & C. F. Baynes, Trans.). San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1933

- Jung, Carl. Gustav. The Red Book. (S. Shamdasani, M. Kyburz, & J. Peck, Trans.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton. 2009

- Mellick, J. The Art of Dreaming. Boston: Conari Press. 2001

- Moacanin, Radmilla. The Essence of Jung’s Psychology and Tibetan Buddhism: Western and Eastern Paths to the Heart.

- Naumburg, M. ‘Art Therapy: Its Scope and Function.’ In E.F. Hammer, The Clinical Application of Projective Drawings (pp. 511–517). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas. 1980

- Violatti, Cristian. ‘Mandala.’ Ancient History Encyclopedia, 07 Sep 2013. Web. 12 Mar 2018.

Categories: Creative Corner, Folk Music, Art and DanceTagged: #mandala, archetypes, art therapy, Buddhism, creative corner, folk art, folklore healing, Jung, Jungian therapy, myth, myth therapy, psychology

법운은 계율을 중시하는 지산의 행보를 거부하다 천천히 계율의 울타리로부터 자유로워지는 지평의 확장을 꾀한다.

법운은 계율을 중시하는 지산의 행보를 거부하다 천천히 계율의 울타리로부터 자유로워지는 지평의 확장을 꾀한다.

집필자

집필자

① 이브 클랭(Yves Klein, 1928-1962)

<이브 클랭이 카시아의 성녀 리타께 바치는 봉헌물 (Ex-voto dédié à Sainte-Rita de Cascia par Yves Klein)>

1961년 / 14×21×3.20cm/ 플랙시글라스, 나사못, 기도문을 적은 종이, 청색 안료, 핑크색 안료, 금박, 소형 금괴