デヴィッド・ボーム

デヴィッド・ジョーゼフ・ボーム(ヘブライ語: דייוויד ג'וֹזף בוֹהם、דוד יוֹסף בוֹהם、英語: David Joseph Bohm、1917年12月20日 - 1992年10月27日)は、理論物理学、哲学、神経心理学およびマンハッタン計画に大きな影響を及ぼした、アメリカ合衆国の物理学者である。

ボームは、ペンシルベニア州ウィルクスバリで、ハンガリー系の父 Samuel Bohm (Böhm) とリトアニア系の母のユダヤ系家庭に生まれた。彼は、家具屋のオーナーでもあり、地域のラビのアシスタントであった父に主に育てられた。ボームはペンシルベニア州立大学を1939年に卒業し、カリフォルニア工科大学に1年間在籍後、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校のロバート・オッペンハイマーの下で理論物理学を学び、ここで博士号を得た。オッペンハイマーの下で学んでいた学生たち(ジョバンニ・ロッシ・ロマニツ, ジョセフ・ワインバーグおよびマックス・フリードマン)の近所で暮らすようになるとともに、徐々に物理学のみならず急進主義者として政治面にものめりこむようになった。オッペンハイマー自身を含めた1930年代後半の多くの若い理想主義者たちのように、ボームは異なる社会モデルに惹かれるとともに、Young Communist League、 the Campus Committee to Fight Conscription、 the Committee for Peace Mobilizationのような団体で活発に活動するようになった。これらの団体は、後にエドガー・フーバー率いるFBIによって、共産主義のレッテルを貼られることとなる。

第二次世界大戦の間、マンハッタン計画は初の原子爆弾の製作のために、バークレイの物理学研究を活用した。オッペンハイマーは、1942年に軍司令官レズリー・グローヴスによって原子爆弾計画のために設置されたトップシークレットの研究所ロスアラモスにボームを誘った。しかし、ボームがすでに政治活動から抜けていたにもかかわらず、彼の友人であるジョセフ・ワインバーグにスパイ(諜報活動)の疑義がかけられていたことから、研究所のセキュリティ基準をクリアできなかった。

ボームはバークレイに残り1943年に博士号を得るまで物理学を教えていた。しかし皮肉なことに、彼が確立した(陽子と重陽子の衝突における)散乱計算がマンハッタン計画に非常に有用であることがわかった途端、彼は研究所に登用された。セキュリティ確認も無いままに、ボームは彼自身の業績にアクセスすることが禁じられ、彼の論文の公開が妨げられるだけではなく、そもそも彼自身が論文を書くこと自体が禁じられたのである。 大学側を満足させるために、オッペンハイマーは彼が成功裏に研究を完了したことを保証した。そして彼は、オークリッジのY-12施設で濃縮ウランを得るための同位体分離装置(カルトロン)について理論計算を実施し、その濃縮ウランは1945年に広島に投下された原子爆弾に用いられることとなる。

第二次世界大戦が終わり、プリンストン大学の助教授(准教授)となったボームは、アルバート・アインシュタインとともに研究を進めていた。1949年の5月、マッカーシズム時代の始まりに、ボームは House Un-American Activities Committeeに過去の社会主義者とのかかわりについて検証するために呼ばれた。しかし、ボームは Fifth amendment を宣言して検証を拒否する権利を主張し、同僚に証拠を提示するのを拒んだ。1950年、Committee の面前での尋問に答えるのを拒否した罪で告発・逮捕された。1951年の5月、彼は無罪放免になったが、すでにプリンストン大学は停職処分を課していた。無罪放免の後、同僚はプリンストン大学での彼のポストを捜し、アインシュタインはアシスタントとしてボームを求めた。しかし、プリンストン大学はボームの契約を更新せず、ボームはサンパウロ大学の物理学学部長の座のためにブラジルに発つこととなる。

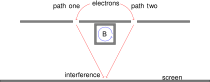

ボームは早い時期に、物理学、特に量子力学や相対性理論において数々の顕著な業績を挙げていた。さらに、バークレーでの大学院生時代には、プラズマの理論を発達させ、ボーム拡散として知られる電子現象を発見した。彼の最初の著書Quantum Theory は1951年に刊行され、アインシュタインやその他の研究者に好意的に受け入れられた。しかし、ボームはその著書に記したようなオーソドックスな量子力学へのアプローチに満足できなくなり、彼ならではのアプローチであるボーム解釈を発展させた。その予想は、非決定的量子理論と完全に一致した。彼の研究とEPRパラドックスは、ジョン・スチュワート・ベルによるベルの不等式の研究を促す主要因となった。

1955年に、ボームはイスラエルに移り、ハイファにあるイスラエル工科大学(Technion)で2年を過ごした。ここで、彼は、妻Saralと出会った。1957年に、ボームはresearch fellowとしてイギリスのブリストル大学に移った。1959年に、ボームは彼の学生であるヤキール・アハラノフとともにアハラノフ=ボーム効果を発見した。これは遮蔽された空間に対して磁場がどのような影響を示すかというものだった。また遮蔽された空間の中でもベクトルポテンシャルが存在することを示すものであった。これは、それまで数学的な簡便さから用いられていたベクトルポテンシャルが、(量子)物理的に実在することを初めて示したものだった。1961年に、ボームはバークベック・カレッジロンドン(BBK)の教授になった。そこでは彼の論文集が保存されている[2]。

バーベック大学在中時、ボームとヒレーは内在、外在秩序の思想を発展させた。[1] [2] ボームとヒレーによると、「もの、すなわち粒子、物質、つまるとことろ、あらゆる対象」は、より深い実在の「比較的自律的で比較的局在的な特徴」として存在するのである。それらの特徴はある条件が成り立つ近似のもとでのみ、独立性を持つと考えられるのである。

ボームの科学的及び哲学的視点は分離できないように見える。1959年、ボームの妻 Saral が図書館でジッドゥ・クリシュナムルティによって書かれた本を見つけてきて、ボームへ薦めた。ボームは彼自身の量子力学における概念とクリシュナムルティの哲学的概念とが歯車のようにかみ合う様子に感銘を受けた。ボームの哲学と物理学に対するアプローチは彼の1980年の書籍Wholeness and the Implicate Order及び1987年の書籍Science, Order and Creativityにおいて表現されている。ボームとクリシュナムルティは25年以上に渡って、哲学と人間性に対する相互の深い関心を抱く親友であった。

ボームはまた、神経心理学や脳機能のホロノミックモデルの発達に関しても大きな理論的貢献をした[3]。 スタンフォード大学の神経心理学者カール・プリブラムとの共同研究で、ボームはプリブラムの基礎理論の確立を助けた。それは、脳は量子力学の原理と波動のパターンの特性に従ってホログラムのように処理を行うという理論だった。 これらの波形はホログラムのように組織化するとボームは考えた。この考えは複雑な波形を正弦波に分解する数学手法であるフーリエ解析の応用に基礎を置く。 プリブラムとボームが発展させた脳のホロノミックモデルはレンズ的な世界観を推し進める。 霧の粒子が太陽光を反射する虹のプリズム効果に似ている。この世界観は慣習的であった「目的」的アプローチとはかなり違う。 どのような条件が世界の見え方を定めるのかを心理学が理解するためには、ボームのような物理学者の考えることを理解するべきである、とプリブラムは考えている。 [3]

ボームは人類や人生全般に対して深い懸念を抱くに至り、人間や自然のアンバランスのみならず、人どうしの間でのアンバランスについて考え警告した。

そして、『人類に起こっていることを考えてみよう。技術は進化を続け、平和利用にも破壊に使われるにしても、どんどん大きな力を持つようになった。』『これらのトラブルの根源は何か? その源泉は基本的に思考の中にある、と私は考える。』と述べるに至った。

このようにして、ボームは著書 "Thought as a System" (TAS) において、思考の幅広く構造的な特性について記している。

ボームは後年に社会問題について言及し、ダイアログと呼ばれる概念を提案した。ボームのダイアログでは対等性、「空っぽの空間」をコミュニケーションの第一の要求とし、人びとのもつ異なる信念を観察することを大切にする。このようなダイアローグが大きなスケールで起きれば、社会に起こる孤立、断片化を克服する助けに成りうると述べた。

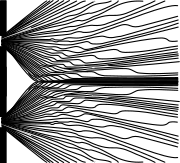

ボームに大きな影響を与えた思想家として、量子論のルイ・ド・ブロイ、ニールス・ボーア、ハイゼンベルク、シュレーディンガー、相対性理論のアルベルト・アインシュタイン、哲人ジッドゥ・クリシュナムルティらがいる。1924年、ド・ブロイ、物質波を提唱。それまで粒子としてしか考えられてこなかった電子には実は「波」が伴う。すべての物質、特に電子には、波が伴うという「物質波」の発想・発見である。ボーム自身は、電子もまた粒子であるだけではなく波のように振舞う物質波であるという物理学上の画期的発見をしたこのド・ブロイに関して、たびたび言及している[4]。しかし、量子力学という枠を超えて、根源的な世界観・宇宙観でボームに影響を与えたのは、上掲の人物の中でも、特にアインシュタインとクリシュナムルティであった[5]。

ボームは1987年に引退するまで量子物理学の研究を続けた。彼の最後の研究は、彼と同僚である Basil Hileyとの長年の共同研究の成果として、死後にThe Undivided Universe: An ontological interpretation of quantum theory (1993) として発行された。彼はまた、ヨーロッパや北米を渡り歩いて、ロンドンの精神科医Patrick de Mare が提唱した概念であるsociotherapy を実践する一手段として、ダイアログの重要性について講演をおこない、また、ダライ・ラマとの一連の会談を行った。

彼は1990年に王立学会特別研究員に選ばれ、1991年にエリオット・クレッソン・メダルを受賞したが、1992年10月27日に心筋梗塞で亡くなった。

- 1951. Quantum Theory, New York: Prentice Hall. 1989 reprint, New York: Dover, ISBN 0-486-65969-0

- 1957. Causality and Chance in Modern Physics, 1961 Harper edition reprinted in 1980 by Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-1002-6

- 1962. Quanta and Reality, A Symposium, with N. R. Hanson and Mary B. Hesse, from a BBC program published by the American Research Council

- 1965. The Special Theory of Relativity, New York: W.A. Benjamin.

- 1976. Fragmentation and Wholeness, The Van Leer Jerusalem Foundation. (『断片と全体』佐野正博訳, 工作舎 , 1985. ISBN 4-87502-101-1)

- 1980. Wholeness and the Implicate Order, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-7100-0971-2, 1983 Ark paperback: ISBN 0-7448-0000-5, 2002 paperback: ISBN 0-415-28979-3

- 1985. Unfolding Meaning: A weekend of dialogue with David Bohm (Donald Factor, editor), Gloucestershire: Foundation House, ISBN 0-948325-00-3, 1987 Ark paperback: ISBN 0-7448-0064-1, 1996 Routledge paperback: ISBN 0-415-13638-5

- 1985. The Ending of Time, with Jiddu Krishnamurti, San Francisco, CA: Harper, ISBN 0-06-064796-5.

- 1987. Science, Order and Creativity, with F. David Peat. London: Routledge. 2nd ed. 2000. ISBN 0-415-17182-2.

- 1991. Changing Consciousness: Exploring the Hidden Source of the Social, Political and Environmental Crises Facing our World (a dialogue of words and images), coauthor Mark Edwards, Harper San Francisco, ISBN 0-06-250072-4

- 1992. Thought as a System (transcript of seminar held in Ojai, California, from November 30 to December 2, 1990), London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11980-4.

- 1993. The Undivided Universe: An ontological interpretation of quantum theory, with B.J. Hiley, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-12185-X (final work)

- 1996. On Dialogue. editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, hardcover: ISBN 0-415-14911-8, paperback: ISBN 0-415-14912-6, 2004 edition: ISBN 0-415-33641-4

- 1998. On Creativity, editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, hardcover: ISBN 0-415-17395-7, paperback: ISBN 0-415-17396-5, 2004 edition: ISBN 0-415-33640-6

- 1999. Limits of Thought: Discussions, with Jiddu Krishnamurti, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-19398-2.

- 1999. Bohm-Biederman Correspondence: Creativity and Science, with Charles Biederman. editor Paavo Pylkkänen. ISBN 0-415-16225-4.

- 2002. The Essential David Bohm. editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26174-0. preface by the Dalai Lama

- アハラノフ=ボーム効果

- ボーム拡散 磁場におけるプラズマでみられる

- ボーム解釈

- Correspondence principle

- EPRパラドックス

- Holomovement

- Implicate and Explicate Order

- ジョン・スチュワート・ベル

- カール・プリブラム

- マッカーシズム

- ジッドゥ・クリシュナムルティ

- 聖真一郎

- "Bohm's Alternative to Quantum Mechanics", David Z. Albert, Scientific American (May, 1994)

- Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller, Herken, Gregg, New York: Henry Holt (2002) ISBN 0-8050-6589-X (information on Bohm's work at Berkeley and his dealings with HUAC)

- Infinite Potential: the Life and Times of David Bohm, F. David Peat, Reading, MA: Addison Wesley (1997), ISBN 0-201-40635-7 DavidPeat.com

- Quantum Implications: Essays in Honour of David Bohm, (B.J. Hiley, F. David Peat, editors), London: Routledge (1987), ISBN 0-415-06960-2

- Thought as a System (transcript of seminar held in Ojai, California, from November 30 to December 2, 1990), London: Routledge. (1992) ISBN 0-415-11980-4.

- The Quantum Theory of Motion: an account of the de Broglie-Bohm Causal Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Peter R. Holland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2000) ISBN 0-521-48543-6

- More about David Bohm's ideas on Dialogue at a German site maintained to carry on his concepts of Dialogue.

- English site for David Bohm's ideas about Dialogue.

- Moderated Dialogue Group Participate in an international English-speaking Bohm Dialogue group, by list server email.

- TT The Table unmoderated Bohm dialogue by private email.

- the David_Bohm_Hub From thingk.net, with compilations of David Bohm's life and work in form of texts, audio, video, and pictures.

- David Bohm and Krishnamurti Skeptical Inquirer, July, 2000, by Martin Gardner.

- Science and exile: David Bohm, the hot times of the Cold War, and his struggle for a new interpretation of quantum mechanics.

- Lifework of David Bohm: River of Truth: Article by Will Keepin

- Dialogos: Consulting group, originally founded by Bohm colleagues William Isaacs and Peter Garrett, aiming to bring Bohm dialogue into organizations.

- Interview with David Bohm provided and conducted by F. David Peat along with John Briggs, first issued in Omni magazine, January 1987

- デビット・ボーム ロンドン大学の森川亮によるボームの紹介。

- ^ David Bohm, Basil J. Hiley, Allan E. G. Stuart: On a new mode of description in physics, International Journal of Theoretical Physics, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 171–183, doi:10.1007/BF00671000, abstract

- ^ David Bohm, F. David Peat: Science, Order, and Creativity, 1987

- ^ [1]

- ^ 2002. The Essential David Bohm. editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26174-0. preface by the Dalai Lama. P142

- ^ “David Bohm was one of the world's greatest quantum mechanical physicists and p

데이비드 폭탄

데이비드 조제프 붐 신경 심리학 및 맨해튼 계획 에 큰 영향을 미친 미국 의 물리학자 이다.

폭탄은 펜실베니아 주 윌크스바리 에서 헝가리계의 아버지 Samuel Bohm (Böhm)과 리투아니아계 어머니의 유태인 가정에서 태어났다. 그는 주로 가구점의 주인이자 지역 랍비 의 조수였던 아버지에게 자랐습니다. 보임은 펜실베니아 주립 대학 을 1939년 에 졸업하고, 캘리포니아 공과 대학 에 1년간 재적 후, 캘리포니아 대학 버클리교의 로버트 오펜하이머 하에서 이론 물리학을 배우고, 여기서 박사 학위 를 얻었다. 오펜하이머 아래에서 배웠던 학생들( 조반니 로시 로마니츠 , 조셉 와인버그 및 맥스 프리드먼 ) 근처에서 살게 됨과 동시에 점차 물리학뿐만 아니라 급진주의자 로서 정치면에도 넘어지게 되었다. 오펜하이머 자신을 포함한 1930년대 후반의 많은 젊은 이상 주의자들 처럼, 폭탄은 다른 사회 모델에 매료되고, Young Communist League , the Campus Committee to Fight Conscription , the Committee for Peace Mobilization 과 같은 단체에서 활발하게 활동하게 됐다. 이 단체들은 나중에 에드거 후버가 이끄는 FBI 에 의해 공산주의 레텔을 붙일 수 있게 된다.

제2차 세계대전 동안 맨해튼 계획 은 최초의 원자폭탄 제작을 위해 버클리의 물리학 연구를 활용했다. 오펜하이머 는 1942년 군사령관 레슬리 그로브스 에 의해 원자폭탄 계획을 위해 설치된 탑 시크릿의 연구소 로스알라모스 에 폭탄을 초대했다. 그러나 폭탄이 이미 정치 활동에서 벗어났음에도 불구하고 그의 친구 인 조셉 와인버그 는 스파이 ( 첩보 활동 )의 의심을 받았기 때문에 연구소의 보안 표준을 지울 수 없습니다. 했다.

폭탄은 버클리에 남아 1943년 에 박사 학위를 얻을 때까지 물리학을 가르쳤다. 그러나 아이러니하게도, 그가 확립한 ( 양자 와 중양자 의 충돌에서) 산란 계산이 맨해튼 계획에 매우 유용하다는 것을 알게 된 순간, 그는 연구소에 등용되었다. 시큐리티 확인도 없는 채로, 폭탄은 그 자신의 업적에 액세스하는 것이 금지되어 그의 논문의 공개가 방해될 뿐만 아니라, 원래 그 자신이 논문을 쓰는 것 자체가 금지된 것이다. 대학 측을 만족시키기 위해, 오펜하이머는 그가 성공적으로 연구를 완료했음을 보증했다. 그리고 그는 오클리 지의 Y-12 시설에서 농축우라늄 을 얻기 위한 동위원소분리장치 (칼트론)에 대한 이론계산을 실시하고, 그 농축우라늄은 1945년 에 히로시마 에 투하된 원자폭탄 에 사용됨 된다.

제2차 세계대전이 끝나고 프린스턴 대학 의 조교수(준교수)가 된 폭탄은 앨버트 아인슈타인 과 함께 연구를 진행하고 있었다. 1949년 5월, 맥아시즘 시대의 시작에서, 폭탄은 House Un-American Activities Committee 에 과거 사회주의자와의 관계를 검증하기 위하여 불렸다. 그러나 폭탄은 Fifth amendment 를 선언하고 검증을 거부할 권리를 주장하고 동료에게 증거를 제시하는 것을 거부했다. 1950년 , Committee의 면전에서의 심문에 대답하는 것을 거부한 죄로 고발·체포되었다. 1951년 5월, 그는 무죄 방면이 되었지만, 이미 프린스턴 대학은 정직 처분을 부과했다. 무죄 방면 후, 동료는 프린스턴 대학에서 그의 포스트를 찾고, 아인슈타인은 조수로 폭탄을 요구했다. 그러나 프린스턴 대학은 폭탄 계약을 갱신하지 않으며 폭탄은 상파울루 대학 의 물리학 학부장의 자리 때문에 브라질 에 출발하게 된다.

폭탄은 이른 시기에 물리학, 특히 양자 역학 과 상대성 이론 에서 수많은 현저한 실적을 꼽았다. 게다가 버클리에서의 대학원생 시대에는 플라즈마 의 이론을 발달시켜 폭탄 확산 으로 알려진 전자 현상을 발견했다. 그의 첫 저서 Quantum Theory 는 1951년 에 간행되어 아인슈타인과 다른 연구자들에게 호의적으로 받아들여졌다. 그러나 폭탄은 저서에 적힌 바와 같이 전통적인 양자 역학에 대한 접근법에 만족할 수 없게 되었고, 그 특유의 접근법인 폭탄 해석을 발전시켰다. 그 기대는 비결정적 양자 이론과 완전히 일치했다. 그의 연구와 EPR 역설 은 존 스튜어트 벨 에 의한 벨 부등식 연구를 촉구하는 주요 요인이 되었다.

1955년에 폭탄은 이스라엘로 옮겨 하이파 에 있는 이스라엘 공과대학 (Technion)에서 2년을 보냈다. 여기서 그는 아내 사랄을 만났다. 1957년에, 폭탄은 research fellow로 영국 브리스톨 대학 으로 옮겼다. 1959년, 폭탄은 그의 학생인 야킬 아할라노프 와 함께 아할라노프=봄 효과 를 발견했다. 이것은 차폐된 공간에 대하여 자기장이 어떤 영향을 나타내는가 하는 것이었다. 또한 차폐 된 공간에서 벡터 잠재력이 있음을 나타냅니다. 이것은, 지금까지 수학적인 간편함으로부터 이용되고 있던 벡터 포텐셜이, (양자) 물리적으로 실재하는 것을 처음으로 나타낸 것이었다. 1961년, 폭탄은 버크벡 칼리지 런던(BBK)의 교수가 되었다. 거기에는 그의 논문집이 보존되어 있다 [2] .

버벡 대학 재중시 폭탄과 힐리 는 내재, 외재질서 사상을 발전시켰다. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] 폭탄과 힐레에 따르면 "물건, 즉 입자, 물질, 막히는 것, 모든 대상"은 더 깊은 실제의 "비교적 자율적이고 상대적으로 국소적인 특징"으로 존재 하는 것이다. 이들의 특징은 특정 조건이 성립하는 근사 하에서만 독립성을 갖는 것으로 생각된다.

폭탄의 과학적 및 철학적 관점은 분리 할 수없는 것처럼 보입니다. 1959년, 폭탄의 아내 Saral이 도서관에서 지두 크리슈나 무르티에 의해 쓰여진 책을 찾아와 폭탄에 추천했다. 폭탄은 그 자신의 양자역학의 개념과 크리슈나 무르티의 철학적 개념이 기어처럼 맞물리는 모습에 감명을 받았다. 폭탄의 철학과 물리학에 대한 접근법은 그의 1980 년 책 Wholeness and the Implicate Order 및 1987 년 책 Science, Order and Creativity 에서 표현되었다. 폭탄과 크리슈나 무르티는 25년 이상 철학과 인간성에 대한 상호 깊은 관심을 안고 있는 가장 친한 친구였다.

폭탄은 또한 신경 심리학과 뇌 기능의 홀로 노믹 모델의 발달에 대한 큰 이론적 기여를했다 [ 3 ] . 스탠포드 대학 의 신경심리학자 인 칼 프리브람 과의 공동 연구에서 폭탄은 프리브람의 기초 이론을 수립하는 데 도움을 주었다. 그것은 뇌가 양자 역학의 원리와 파동 패턴의 특성에 따라 홀로그램 처럼 처리를 수행하는 이론이었다. 이 파형은 홀로그램처럼 조직화된다고 폭탄은 생각했다. 이 아이디어는 복잡한 파형을 사인파 로 분해하는 수학 기법 인 푸리에 분석 의 응용에 기초합니다. 프리브람과 폭탄이 발전시킨 뇌의 홀로노믹 모델은 렌즈적인 세계관을 추진한다. 안개 입자는 태양광을 반사하는 무지개의 프리즘 효과와 유사합니다. 이 세계관은 관습적이었던 "목적"적 접근과는 상당히 다르다. 심리학이 어떤 조건이 세계의 보이는 법을 결정하는지 이해하기 위해서는 폭탄과 같은 물리학자의 생각을 이해해야한다고 프리브람은 생각합니다. [3]

폭탄은 인류와 인생 전반에 대해 깊은 우려를 안고 인간과 자연의 불균형뿐만 아니라 사람 사이의 불균형에 대해 생각 경고했다.

그리고 『인류에게 일어나고 있는 일을 생각해 보자. 기술은 진화를 계속해 평화이용에도 파괴에 사용되더라도 점점 큰 힘을 갖게 되었다. 『『이런 트러블의 근원은 무엇인가? 그 원천은 기본적으로 사고 속에 있다, 라고 나는 생각한다. 」라고 말하기에 이르렀다.

이러한 방식으로 폭탄은 저서 "Thought as a System" (TAS)에서 사고의 광범위하고 구조적인 특성을 설명합니다.

폭탄은 나중에 사회 문제에 대해 언급하고 대화라는 개념을 제안했다. 폭탄 대화상자에서는 대등성, 「빈 공간」을 커뮤니케이션의 제일의 요구로 하고, 사람들이 가지는 다른 신념을 관찰하는 것을 소중히 한다. 이러한 대화가 큰 규모로 일어나면 사회에 일어나는 고립, 단편화를 극복하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다고 말했다.

폭탄에 큰 영향을 미친 사상가로서 양자론 루이 드 브로이 , 닐스 보어, 하이젠베르크, 슈레이딩거, 상대성 이론의 알버트 아인슈타인 , 철인 지두 크리슈나 무르티 등이 있다. 1924년, 드 브로이, 물질파를 제창. 그때까지 입자로서 밖에 생각되지 않았던 전자에는 실은 '파도'가 수반된다. 모든 물질, 특히 전자에는 파가 수반한다는 '물질파'의 발상·발견이다. 폭탄 자체는 전자가 입자 일뿐만 아니라 파도처럼 행동하는 물질파라는 물리학 적으로 획기적인 발견을 한이 드 브로이에 대해 종종 언급하고있다 [ 4 ] . 그러나 양자역학이라는 틀을 넘어 근원적인 세계관·우주관에서 폭탄에 영향을 준 것은 위의 인물 중에서도 특히 아인슈타인과 크리슈나 무르티였다 [ 5 ] .

폭탄은 1987년 에 은퇴할 때까지 양자 물리학의 연구를 계속했다. 그의 마지막 연구는 그와 동료인 Basil Hiley 와의 오랜 공동 연구의 결과로서 사후에 The Undivided Universe: An ontological interpretation of quantum theory (1993)로 발행되었다. 그는 또한 유럽과 북미를 건너 런던의 정신과 의사 Patrick de Mare가 제창 한 개념 인 sociotherapy를 실천하는 수단으로서 대화의 중요성에 대해 강연을하고, 달라이 라마 와의 일련 의 회담을 실시했다.

그는 1990년 에 왕립학회 특별연구원 으로 선정되어 1991년에 엘리엇 크레슨 메달을 수상했지만 1992년 10월 27일 심근 경색 으로 사망했다.

- 1951. Quantum Theory , New York: Prentice Hall. 1989 reprint, New York: Dover, ISBN 0-486-65969-0

- 1957. Causality and Chance in Modern Physics , 1961 Harper edition reprinted in 1980 by Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-1002-6

- 1962. Quanta and Reality, A Symposium , with NR Hanson and Mary B. Hesse , from a BBC program published by the American Research Council

- 1965. The Special Theory of Relativity , New York: WA Benjamin.

- 1976. Fragmentation and Wholeness , The Van Leer Jerusalem Foundation.

- 1980. Wholeness and the Implicate Order , London: Routledge, ISBN 0-7100-0971-2 , 1983 Ark paperback: ISBN 0-7448-0000-5 , 2002 paperback: ISBN 0-415-2897

- 1985. Unfolding Meaning: A weekend of dialogue with David Bohm (Donald Factor, editor), Gloucestershire: Foundation House, ISBN 0-948325-00-3 , 1987 Ark paperback: ISBN 0-7448-0064-1 , ISBN 0-415-13638-5

- 1985. The Ending of Time , with Jiddu Krishnamurti, San Francisco, CA: Harper, ISBN 0-06-064796-5 .

- 1987. Science, Order and Creativity , with F. David Peat . London: Routledge. 2nd ed. 2000. ISBN 0-415-17182-2 .

- 1991. Changing Consciousness: Exploring the Hidden Source of the Social, Political and Environmental Crises Facing our World (a dialogue of words and images), coauthor Mark Edwards, Harper San Francisco, ISBN 0-06-250072-4

- 1992. Thought as a System (transcript of of seminar held in Ojai, California , from November 30 to December 2, 1990), London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11980-4 .

- 1993. The Undivided Universe: An ontological interpretation of quantum theory , with BJ Hiley , London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-12185-X (final work)

- 1996. On Dialogue . editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, hardcover: ISBN 0-415-14911-8 , paperback: ISBN 0-415-14912-6 , 2004 edition: ISBN 0-415-33641-4

- 1998. On Creativity , editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, hardcover: ISBN 0-415-17395-7 , paperback: ISBN 0-415-17396-5 , 2004 edition: ISBN 0-415-33640-6

- 1999. Limits of Thought: Discussions , with Jiddu Krishnamurti, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-19398-2 .

- 1999. Bohm-Biederman Correspondence: Creativity and Science , with Charles Biederman. editor Paavo Pylkkänen. ISBN 0-415-16225-4 .

- 2002. The Essential David Bohm . editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26174-0 . preface by the Dalai Lama

- 아할라노프 = 폭탄 효과

- 폭탄 확산 자기장에서 플라즈마에서 발견

- 폭탄 해석

- Correspondence principle

- EPR 역설

- Holomovement

- Implicate and Explicate Order

- 존 스튜어트 벨

- 칼 프리브람

- 맥카시즘

- 지두 크리슈나 무르티

- 세이 신이치로

- "Bohm's Alternative to Quantum Mechanics", David Z. Albert, Scientific American (May, 1994)

- Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller , Herken, Gregg, New York: Henry Holt (2002) ISBN 0-8050-6589-X (information on Bohm's work at Berkeley and his dealings with HUAC )

- Infinite Potential: the Life and Times of David Bohm , F. David Peat, Reading, MA: Addison Wesley (1997), ISBN 0-201-40635-7 DavidPeat.com

- Quantum Implications: Essays in Honour of David Bohm , (BJ Hiley, F. David Peat, editors), London: Routledge (1987), ISBN 0-415-06960-2

- Thought as a System (transcript of of seminar held in Ojai, California, from November 30 to December 2, 1990), London: Routledge. (1992) ISBN 0-415-11980-4 .

- The Quantum Theory of Motion: an account of the de Broglie-Bohm Causal Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics , Peter R. Holland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2000) ISBN 0-521-48543-6

- More about David Bohm's ideas on Dialogue at a German site maintained to carry on his concepts of Dialogue.

- English site for David Bohm's ideas about Dialogue.

- Moderated Dialogue Group Participate in an international English-speaking Bohm Dialogue group, by list server email.

- TT The Table unmoderated Bohm dialogue by private email.

- the David_Bohm_Hub From thingk.net, with compilations of David Bohm's life and work in form of texts, audio, video, and pictures.

- David Bohm and Krishnamurti Skeptical Inquirer , July, 2000, by Martin Gardner.

- Science and exile : David Bohm, the hot times of the Cold War, and his struggle for a new interpretation of quantum mechanics.

- Lifework of David Bohm: River of Truth : Article by Will Keepin

- Dialogos : Consulting group, originally founded by Bohm colleagues William Isaacs and Peter Garrett, aiming to bring Bohm dialogue into organizations.

- Interview with David Bohm provided and conducted by F. David Peat along with John Briggs, first issued in Omni magazine, January 1987

- 직불 폭탄 런던 대학 의 모리카와 료 에 의한 폭탄 소개.

- ↑ David Bohm, Basil J. Hiley , Allan E. G. Stuart: On a new mode of description in physics , International Journal of Theoretical Physics, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 171–183, doi : 10.1007/BF006710

- ↑ David Bohm, F. David Peat: Science, Order, and Creativity , 1987

- ^ [1]

- ↑ 2002. The Essential David Bohm. editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26174-0 . preface by the Dalai Lama. P142

- ↑ “David Bohm was one of the world's greatest quantum mechanical physicists and philosophers and was deeply influenced by both J. Krishnamurti and Einstein.” http://homepages.ihug.co.nz/~sai/Bohm.html

데이비드 봄

데이비드 봄 | |

데이비드 봄 | |

| 출생 | 1917년 12월 20일 미국 펜실베이니아주 윌크스배리 |

|---|---|

| 사망 | 1992년 10월 27일 영국 잉글랜드 런던 |

| 국적 | 미국-브라질-영국 |

| 출신 학교 | 펜실베이니아 주립 대학교 캘리포니아 공과대학교 캘리포니아 대학교 버클리 |

| 주요 업적 | 아로노프-봄 효과 드 브로이-봄 이론 |

| 수상 | 1991 엘리엇 크레슨 메달 1990 왕립 학회 펠로우 |

| 분야 | 이론물리학 |

| 소속 | 프린스턴 대학교 상파울루 대학교 테크니온 브리스틀 대학교 런던 대학교 버크벡 칼리지 |

| 박사 지도교수 | 로버트 오펜하이머 |

| 박사 지도학생 | 야키르 아로노프 데이비드 파인스 제프리 버브 앙리 보르토프트 유진 P. 그로스 |

| 영향을 받음 | 알베르트 아인슈타인 지두 크리슈나무르티 |

| 영향을 줌 | 존 스튜어트 벨 피터 센지 |

데이비드 조세프 봄 왕립학회 회원[1] (영어: David Joseph Bohm, [déivid ʤóuzəf boʊm]; 1917년 12월 20일 - 1992년 10월 27일)은 20세기의 가장 중요한 이론물리학자 중 한 사람으로 일컬어지는[2] 또한 양자 이론, 신경심리학 및 심리철학에 비정통파 아이디어에 공헌한 미국-브라질-영국 과학자이다. 물리학에 대한 그의 많은 공헌 중에는 현재 드 브로이-봄 이론으로 알려진 양자 이론에 대한 인과적 결정론적 해석이 있다.

봄은 양자 물리학이 현실에 대한 오래된 데카르트적 모형(Cartesian model)(어떻게든 상호 작용하는 두 종류의 물질, 정신적 물질과 물리적 물질이 있음)이 너무 제한적이라는 견해를 발전시켰다. 이를 보완하기 위해 그는 "함축적" 및 "설명적" 질서("implicate" and "explicate" order)의 수학적 물리적 이론을 개발했다.[3] 그는 또한 뇌가 세포 수준에서 일부 양자 효과의 수학에 따라 작동한다고 믿었으며 사고는 양자 존재처럼 분산되고 비국소화된다고 가정했다.[4] 봄의 주요 관심사는 일반적으로 현실의 본질을 이해하는 것과 특히 일관된 전체로서 의식을 이해하는 것이었는데, 봄에 따르면 이는 결코 정적이거나 완전하지 않다.[5]

봄은 만연한 이성과 기술의 위험성에 대해 경고하면서 대신 진정으로 보완적(supportive) 대화의 필요성을 주장했다. 대화는 사회 세계에서 갈등과 골칫거리를 확장하고 통합할 수 있다고 주장했다. 여기서 그의 인식론은 그의 존재론을 반영했다.[6]

미국에서 태어난 봄은 캘리포니아 대학교 버클리에서 로버트 오펜하이머 밑에서 박사 학위를 취득했다. 그는 공산주의자였기 때문에 1949년 연방 정부의 조사 대상이 되었고, 그로 인해 미국을 떠나게 되었다. 그는 여러 나라에서 경력을 쌓아 처음에는 브라질인이 되었고 그 다음에는 영국 시민(British citizen)이 되었다. 그는 1956년 헝가리 봉기 이후 마르크스주의를 포기했다.[7][8]

봄은 펜실바니아 주 윌크스배리에서 헝가리계 유대인 이민자 아버지 사무엘 봄Samuel Bohm[9]과 리투아니아계 유대인 어머니 사이에서 태어났다. 그는 주로 가구점 주인이자 지역 랍비의 조수인 아버지 밑에서 자랐다. 유대인 가정에서 자랐음에도 불구하고 그는 십대에 불가지론자가 되었다.[10] 봄은 펜실대학교 주립대(현재 펜실베이니아 주립 대학교)에 다녀서 1939년에 졸업했고, 그 후 캘리포니아 공과대학교에서 1년을 보냈다. 그후 그는 캘리포니아 대학교 버클리 방사선 연구소의 로버트 오펜하이머가 이끄는 이론물리학 그룹으로 옮겨 박사 학위를 취득했다.

봄은 오펜하이머의 다른 대학원생들(조반니 로시 로마니츠Giovanni Rossi Lomanitz, 조셉 와인버그Joseph Weinberg, 맥스 프리드먼Max Friedman)과 같은 동네에 살았고 그들과 함께 급진 정치에 점점 더 관여하게 되었다. 그는 젊은 공산주의자 동맹(Young Communist League), 징병 반대 캠퍼스 위원회(Campus Committee to Fight Conscription), 평화 동원 위원회(American Peace Mobilization)를 포함하여 공산주의 및 공산주의 지원 조직에서 활발히 활동했다. 방사선 연구소에서 근무하는 동안 봄은 미래의 베티 프리던과 관계를 맺었고 또한 산업 조직 회의(Congress of Industrial Organizations)(CIO)에 소속된 소규모 노동 조합인 건축가, 엔지니어, 화학자 및 기술자 연합(Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists, and Technicians)의 지역 지부를 조직하는 데 도움을 주었다.[11]

제2차 세계대전 동안 맨해튼 프로젝트는 최초의 원자 폭탄을 생산하기 위한 노력으로 버클리의 물리학 연구의 많은 부분을 동원했다. 오펜하이머는 봄에게 로스앨러모스(원자 폭탄을 설계하기 위해 1942년에 설립된 일급 비밀 연구소)에서 그와 함께 일할 것을 요청했지만, 프로젝트 책임자인 레슬리 그로브스 준장은 그의 정치성과 간첩 혐의를 받고 있던 와인버그Weinberg와의 가까운 우정에 대한 증거들을 본 후에 봄의 보안 허가를 승인하지 않았다.

전쟁 중에 봄은 버클리에 남아서 물리학을 가르쳤고 또한 플라스마, 싱크로트론(synchrotron) 및 싱크로사이클로트론(Synchrocyclotron)에 대한 연구를 수행했다. 그는 특이한 상황으로 1943년에 PhD를 마쳤다. 전기 작가 F. 데이비드 피트David Peat에 따르면[12], "그가 완성한 산란 계산(양성자와 중수소의 충돌)은 맨해튼 프로젝트에 유용한 것으로 판명되었고 또한 즉시 비밀로 분류되었다. 보안 인가가 없었던 봄은 자신의 논문에 대한 접근이 거부되었으며, 자신의 논문을 옹호하는 것이 금지되었을 뿐만 아니라, 애초부터 자신의 논문을 쓰는 것조차 허용되지 않았다!" 오펜하이머는 대학교를 만족시키기 위해 봄이 연구를 성공적으로 완료했음을 인증했다. 봄은 나중에 테네시 주 오크리지에 있는 Y-12 시설에서 1945년 히로시마에 투하된 원자폭탄의 우라늄 농축에 사용된 캘루트론에 대한 이론적인 계산을 수행했다.

전쟁이 끝난 후 봄은 프린스턴 대학교의 조교수가 되었다. 그는 또한 인근 고등 연구소에서 알베르트 아인슈타인과도 가깝게 연구했다. 1949년 5월, 하원 비미 활동 위원회는 봄이 이전에 노동조합과 연관과 공산주의자로 의심되는 관계에 있었기 때문에 증언할 것을 요구했다. 봄은 증언을 거부할 수 있는 수정헌법 5조를 주장했고 동료들에 대한 증거 제공을 거부했다.

1950년에 봄은 위원회의 질문에 답변을 거부한 혐의로 체포되었다. 그는 1951년 5월에 무죄를 선고받았지만 프린스턴은 이미 그를 정직시켰다. 봄의 무죄 판결 후 동료들은 그를 프린스턴에 복직시키려고 했지만 해롤드 W. 도즈Harold W. Dodds 프린스턴 총장[13]은 봄의 재계약을 하지 않기로 결정했다. 아인슈타인은 그를 연구소의 연구 조교로 임명하는 것을 고려했지만 오펜하이머(1947년부터 연구소의 소장을 역임했다)는 "이 아이디어에 반대했고 [...] 그의 이전 학생에게 나라를 떠나라고 조언했다."[14] 맨체스터 대학교로 가려는 그의 요청은 아인슈타인의 지원을 받았지만 성공하지 못했다.[15] 봄은 제이미 티옴노Jayme Tiomno의 초청과 아인슈타인과 오펜하이머의 추천으로 상파울루 대학교의 물리학 교수직을 맡기 위해 브라질로 떠났다.

그의 초년 동안, 봄은 물리학, 특히 양자역학 및 상대성이론에 많은 중요한 공헌을 했다. 버클리에서 대학원생으로서 그는 플라스마 이론을 개발하여 현재 봄 확산(Bohm diffusion)으로 알려진 전자 현상을 발견했다.[17] 1951년에 출판된 그의 첫 번째 책인 《양자 이론(Quantum Theory)》은 특히 아인슈타인에게 좋은 평가를 받았다. 그러나 봄은 그가 그 책에서 쓴 양자 이론의 정통적인 해석에 불만을 갖게 되었다. 양자역학의 WKB 근사가 결정론적 방정식으로 이어진다는 사실과 단순한 근사만으로는 확률론을 결정론적 이론으로 바꿀 수 없다는 인식에서 출발하여 그는 양자역학에 대한 기존 접근 방식의 불가피성을 의심했다.[18]

봄의 목표는 결정론적, 기계적 관점을 설정하는 것이 아니라 기존의 접근 방식과 달리 속성을 근본적인 실재에 귀속시키는 것이 가능하다는 것을 보여주는 것이었다.[19] 그는 자신의 해석(드 브로이-봄 이론, 파일럿 파동 이론이라고도 함)을 개발하기 시작했으며, 그 예측은 비결정론적 양자 이론과 완벽하게 일치했다. 그는 처음에 그의 접근 방식을 숨은 변수 이론이라고 불렀지만, 나중에 그의 이론에 의해 기술된 현상의 기저를 이루는 확률 과정이 언젠가 발견될 수 있다는 그의 견해를 반영하여 이를 '존재론적 이론'이라고 불렀다. 봄과 그의 동료인 바질 하일리Basil Hiley는 나중에 "숨은 변수에 대한 해석"이라는 용어의 선택이 너무 제한적이라는 사실을 발견했다고 말했다. 특히 변수, 위치 및 운동량이 "실제로 숨겨져 있지 않기" 때문이다.[20]

봄의 연구와 EPR 역설은 국소적 숨은 변수 이론을 배제하는 존 스튜어트 벨의 벨 부등식을 유발하는 주요 요인이 되었다. 벨의 연구의 전체 결과는 여전히 조사되고 있다.

1951년 10월 10일 봄이 브라질에 도착한 후 상파울루 주재 미국 영사는 그의 여권을 압수했고, 그가 고국으로 돌아가야만 찾을 수 있다고 고지함으로써 그는 공포스럽게 했고,[21] 그가 유럽 여행을 희망했었기 때문에, 그의 사기가 크게 떨어진 것으로 알려졌다. 그는 브라질 시민권을 신청해서 받았지만, 법률에 따라 미국 시민권을 포기해야만 했다. 그는 소송을 제기하고 나서 단지 수십 년 후인 1986년에 야 그것을 되찾을 수 있었다.[22]

봄은 상파울루 대학에서 1952년 그의 출판물의 주제가 된 인과 이론에 대해서 연구했다. 장피에르 비지에Jean-Pierre Vigier는 상파울루로 여행을 가서 봄과 3개월 동안 일했고; 우주론자 피터 버그만Peter Bergmann의 제자인 랄프 쉴러Ralph Schiller는 2년 동안 그의 조수였으며; 그는 티옴노Tiomno 및 발터 쉬처Walther Schützer와 함께 일했고; 또한 마리오 번지Mario Bunge는 1년 동안 그와 함께 일했다. 그는 브라질의 물리학자 마리오 쉔버그Mário Schenberg, 장 마이어Jean Meyer, 레이테 로페스Leite Lopes와 접촉했으며, 그의 작업에서 그를 격려하고 자금 조달을 도왔던 리처드 파인만, 이지도어 아이작 라비, 레온 로젠펠드Léon Rosenfeld, 카를 프리드리히 폰 바이츠제커, 허버트 엘. 앤더슨Herbert L. Anderson, 도날드 커스트Donald Kerst, 마르코스 모신스키Marcos Moshinsky, 알레한드로 메디나Alejandro Medina 및 하이젠베르크의 전 조수인 귀도 벡Guido Beck를 비롯한 브라질 방문객들과 때때로 토론을 했다. 브라질 국가 과학 기술 개발 위원회(CNPq)는 인과 이론에 대한 그의 작업을 명시적으로 지원하고 봄 주변의 여러 연구원에게 자금을 지원했다. 비지에와 그의 작업은 특히 마델룽Madelung이 제안한 유체 역학 모델과의 연결에 대해 루이 드 브로이와 둘 사이의 오랜 협력의 시작이었다.[23] 그러나 인과 이론은 많은 저항과 회의론에 부딪쳤고 많은 물리학자들은 코펜하겐 해석이 양자 역학에 대한 유일한 실행 가능한 접근 방식이라고 주장했다.[22]

1951년부터 1953년까지 봄과 데이비드 파인스David Pines는 랜덤 위상 근사(Random phase approximation)를 소개하고 플라즈몬을 제안한 소논문들을 발표했다.[24][25][26]

1955년 봄은 이스라엘로 이주하여 하이파의 테크니온에서 2년 동안 일했다. 그곳에서 그는 1956년에 결혼한 사라("사랄") 울프슨Sarah("Saral") Woolfson을 만났다.

1957년 봄과 그의 제자 야키르 아하로노프Yakir Aharonov는 아인슈타인-포돌스키-로젠 (EPR) 역설의 새로운 버전을 출판하여 스핀의 관점에서 원래 주장을 재구성했다.[27] 존 스튜어트 벨이 1964년 그의 유명한 논문에서 논의한 것은 EPR 역설의 그런 형태였다.[28]

1957년 봄은 브리스톨 대학교의 연구원으로 영국으로 이주했다. 1959년에 봄과 아하로노프는 자기장이 차폐된 공간 영역에 어떻게 영향을 미칠 수 있고 반면에 그 벡터 퍼텐셜은 그곳에서 사라지지 않음을 보여주는 아하로노프-봄 효과를 발견하였다. 이것은 지금까지 수학적으로 편리했던 자기 벡터 퍼텐셜(Magnetic vector potential)이 실제 물리적(양자) 효과를 가질 수 있음을 처음으로 보여주었다.

1961년에 봄은 런던 대학교의 버크벡 칼리지에서 이론물리학 교수가 되었고, 1987년에 명예교수가 되었다. 그의 수집된 논문은 그곳에 보관되어 있다.[29]

버크벡 칼리지에서 봄과 바질 하일리Basil Hiley의 많은 작업은 봄이 제안한 함축적, 설명적 그리고 생성적 질서의 개념을 확장했다.[3][30][31] 봄과 힐리의 관점에서 "사물, 입자와 같은 것, 물체 및 실제로 주체"는 기본적 활동(underlying activity)의 "반자율적 준국소적 특징"으로서 존재한다. 이러한 기능은 특정 기준이 충족되는 특정 수준의 근사까지만 독립적인 것으로 간주될 수 있다. 그 그림에서 작용 함수가 플랑크 상수보다 훨씬 크지 않다는 조건에서 양자 현상에 대한 고전적 한계(classical limit)는 그러한 기준 중 하나를 나타낸다. 그들은 그러한 질서에서의 활동에 대해 "홀로무브먼트(holomovement)"라는 단어를 사용했다.[32]

봄은 스탠퍼드 대학교의 신경과학자 칼 H. 프리브람Karl H. Pribram과 공동으로 뇌 기능의 홀로노믹 모형의 초기 개발에 참여했다. 이 모형은 일반적으로 받아들여지는 아이디어와 크게 다른 인간 인지 모형이다.[4] 봄은 양자 수학적 원리와 파동 패턴의 특성에 따라 뇌가 홀로그램과 유사한 방식으로 작동한다는 이론을 프리브람과 함께 연구했다.[33]

그의 과학적 연구 외에도 봄은 개인과 사회에서 관심, 동기 부여 및 갈등과 관련된 사고의 역할에 특히 관심을 가지고 의식의 본질을 탐구하는 데 깊은 관심을 보였다. 이러한 관심은 마르크스주의 이데올로기와 헤겔 철학에 대한 그의 초기 관심의 자연스러운 확장이었다. 그의 견해는 1961년부터 철학자, 연설가, 작가인 지두 크리슈나무르티와의 광범위한 상호작용을 통해 더욱 명확해졌다.[34][35] 그들의 협력은 25년 동안 지속되었으며 녹음된 대화는 여러 권으로 출판되었다.[36][37][38]

봄의 크리슈나무르티 철학에 대한 장기간의 관여는 그의 과학자들 중 일부에 의해 다소 회의적인 것으로 간주되었다.[39][40] 두 사람 사이의 관계에 대한 보다 최근의 광범위한 조사는 이를 보다 긍정적인 관점에서 제시하고 심리학 분야에서 봄의 작업이 이론 물리학에 대한 그의 공헌과 상보적이고 양립할 수 있음을 보여준다.[35]

심리학 분야에 대한 봄의 관점의 성숙한 표현은 캘리포니아 오하이에 있는 크리슈나무르티가 설립한 오크 그로브 스쿨(Oak Grove School)에서 1990년에 실시된 세미나에서 발표되었다. 그것은 오크 그로브 스쿨에서 봄이 개최한 일련의 세미나 중 하나였으며, 그것은 《시스템으로서의 사고(Thought as a System)》로 출판되었다.[41] 세미나에서 봄은 생각의 본질과 그것이 일상 생활에 미치는 영향에 대한 많은 잘못된 가정을 포함하여 사회 전반에 퍼져 있는 생각의 영향을 설명했다.

세미나에서 봄은 몇 가지 상호 관련된 주제를 개발한다. 그는 사고가 개인, 사회, 과학 등 모든 종류의 문제를 해결하는 데 사용되는 어디에나 있는 도구(ubiquitous tool)이라고 지적한다. 그러나 그는 사고가 무심코 많은 문제의 원인이기도 하다고 주장한다. 그는 상황의 아이러니를 인식하고 인정한다. 마치 의사에게 가서 병에 걸리는 것과 같다.[35][41]

봄은 사고가 개인과 사회 전반에 걸쳐 원활하게 전달되는 개념, 아이디어 및 가정의 상호 연결된 네트워크라는 의미에서 시스템이라고 주장한다. 그러므로 사고의 기능에 결함이 있다면 그것은 전체 네트워크를 감염시키는 시스템적 결함임에 틀림없다. 따라서 주어진 문제를 해결하기 위해 가져오는 사고는 해결하려는 문제를 만든 동일한 결함에 취약하다.[35][41]

사고는 그저 객관적으로 보고하는 것처럼 진행되지만, 실제로는 종종 예상치 못한 방식으로 인식을 착색하고 왜곡하기도 한다. 봄에 따르면 사고에 의해 도입된 왜곡을 수정하기 위해 필요한 것은 일종의 고유 수용 또는 자기 인식이다. 몸 전체의 신경 수용체는 우리의 신체적 위치와 움직임을 직접적으로 알려주지만 사고의 활동에 대한 그에 상응하는 인식은 없다. 그러한 인식은 심리적 고유 수용성을 나타내며 사고 과정의 의도하지 않은 결과를 인식하고 수정할 수 있는 가능성을 가능하게 한다.[35][41]

봄은 일반 의미론 분야를 발전시킨 폴란드계 미국인 알프레드 코르지브스키Alfred Korzybski의 말을 인용하여 자신의 저서 《창조성에 대해(On Creativity)》에서 "형이상학은 세계관의 표현"이며 "따라서 형이상학을 일종의 예술 형식으로 간주해야 하며, 전체로서의 현실에 대해 참된 것을 말하려는 시도라기보다는 어떤 면에서는 시를, 다른 면에서는 수학을 닮았다."[42]

봄은 과학적 주류를 벗어난 다양한 아이디어를 예리하게 인식했다. 봄은 그의 책 《과학, 질서와 창조성(Science, Order and Creativity)》에서 루퍼트 샐드레이크Rupert Sheldrake를 포함하여 종의 진화에 대한 다양한 생물학자의 견해를 언급했다.[43] 그는 또한 빌헬름 라이히의 사상을 알고 있었다.[44]

다른 많은 과학자들과 달리 봄은 초자연적인 현상을 배제하지 않았다. 봄은 심지어 유리 겔러의 열쇠와 숟가락 구부리기가 가능하다고 일시적으로 생각했으며, 그의 동료인 바질 하일리Basil Hiley는 물리학에서 그들의 연구에 대한 과학적 신뢰성을 훼손할 수 있다고 경고했다. 마틴 가드너는 《스켑티칼 인콰이어러(Skeptical Inquirer)》 기사에서 이를 보고했고, 또한 봄이 1959년에 만났고 이후에 많은 교류를 가졌던 지두 크리슈나무르티의 견해를 비판했다. 가드너는 정신과 물질의 상호 연결성에 대한 봄의 견해(한번은 그가 "전자조차도 어떤 수준의 정신이 고지된다"[45]고 요약했다.)는 "범심론(panpsychism)과의 유희였다"라고 말했다.[40]

말년의 사회 문제를 해결하기 위해서, 봄은 "봄 대화(Bohm Dialogue)"로 알려진, 동등한 지위와 "자유 공간"이 의사 소통의 가장 중요한 전제 조건과 다양한 개인 신념들에 대한 이해를 형성하는 해결책에 대한 제안서를 작성했다. 이러한 형태의 대화에서 필수적인 요소는 참가자가 즉각적인 행동이나 판단을 "중단"하고 자신과 서로에게 사고 과정 자체를 인식할 기회를 주는 것이다. 봄은 "대화 그룹"이 충분히 넓은 규모로 경험된다면 봄이 사회에서 관찰한 고립과 파편화를 극복하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다고 제안했다.

봄은 1987년 은퇴한 후에도 양자 물리학에서 그의 작업을 계속했다. 사후에 출판된 그의 마지막 작업인 《분할되지 않은 우주: 양자 이론의 존재론적 해석(The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory)》 (1993)은 바질 하일리Basil Hiley와의 수십 년 간의 협력의 결과였다. 그는 또한 사회 요법의 한 형태로서 대화의 중요성에 대해 유럽과 북미 전역의 청중들에게 런던의 정신과 의사이자 그룹 분석(Group Analysis)의 실무자인 패트릭 드 마레Patrick de Maré에게서 차용한 개념에 대해 이야기했으며, 또한 달라이 라마와 일련의 회의를 했다. 그는 1990년에 왕립학회의 펠로우(Fellow of the Royal Society)로 선출되었다.[1]

삶이 끝나갈 무렵, 봄은 이전에 겪었던 우울증의 재발을 경험하기 시작했다. 그는 1991년 5월 10일 사우스런던의 모즐리 병원(Maudsley Hospital)에 입원했다. 그의 상태는 악화되었고 그를 도울 수 있는 유일한 치료법은 전기 경련 요법이라고 결정되었다. 봄의 아내는 봄의 오랜 친구이자 협력자인 정신과 의사인 데이비드 샤인버그David Shainberg와 상담했으며, 봄은 전기 경련 치료가 아마도 그의 유일한 선택일 것이라는 데 동의했다. 봄은 치료를 통해 개선된 모습을 보여 8월 29일에 퇴원했지만 우울증이 재발하여 약물 치료를 받았다.[46]

봄은 1992년 10월 27일 런던의 헨던에서 심장마비로 74세의 나이로 사망했다.[47]

영화 《무한한 퍼텐셜(Infinite Potential)》은 봄의 삶과 연구를 기반으로 한다. F. 데이비드 피트F. David Peat의 전기와 같은 이름을 채택한다.[48]

1950년대 초, 봄의 숨겨진 변수에 대한 인과 양자 이론은 대부분 부정적인 인식을 받았으며 물리학자들 사이에서는 봄 개인적 및 그의 아이디어를 모두 무시하는 경향이 널리 퍼졌었다. 1950년대 후반과 1960년대 초반에 봄의 아이디어에 대한 관심이 크게 부활했다; 1957년 브리스톨에서 열린 콜스턴 연구회(Colston Research Society)의 9차 심포지엄은 그의 아이디어에 대한 더 큰 관용으로 가는 중요한 전환점이 되었다.[49]

- 1951. Quantum Theory, New York: Prentice Hall. 1989 reprint, New York: Dover

- 1957. Causality and Chance in Modern Physics, 1961 Harper edition reprinted in 1980 by Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania Press

- 1962. Quanta and Reality, A Symposium, with N. R. Hanson and Mary B. Hesse, from a BBC program published by the American Research Council

- 1965. The Special Theory of Relativity, New York: W.A. Benjamin.

- 1980. Wholeness and the Implicate Order, London: Routledge; 1983 Ark paperback; 2002 paperback

- 1985. Unfolding Meaning: A weekend of dialogue with David Bohm (Donald Factor, editor), Gloucestershire: Foundation House; 1987 Ark paperback; 1996 Routledge paperback

- 1985. The Ending of Time, with Jiddu Krishnamurti, San Francisco: Harper

- 1987. Science, Order, and Creativity, with F. David Peat. London: Routledge. 2nd ed. 2000.

- 1989. Meaning And Information, In: P. Pylkkänen (ed.): The Search for Meaning: The New Spirit in Science and Philosophy, Crucible, The Aquarian Press, 1989.

- 1991. Changing Consciousness: Exploring the Hidden Source of the Social, Political and Environmental Crises Facing our World (a dialogue of words and images), coauthor Mark Edwards, Harper San Francisco

- 1992. Thought as a System (transcript of seminar held in Ojai, California, from 30 November to 2 December 1990), London: Routledge.

- 1993. The Undivided Universe: An ontological interpretation of quantum theory, with B.J. Hiley, London: Routledge, (final work)

- 1996. On Dialogue. editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge; 2004 edition

- 1998. On Creativity, editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge; 2004 edition

- 1999. Limits of Thought: Discussions, with Jiddu Krishnamurti, London: Routledge

- 1999. Bohm–Biederman Correspondence: Creativity and Science, with Charles Biederman. editor Paavo Pylkkänen

- 2002. The Essential David Bohm. editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, preface by the Dalai Lama 2017. David Bohm: Causality and Chance, Letters to Three Women, editor Chris Talbot. Cham, Switzerland: Springer

- 2018. The Unity of Everything: A Conversation with David Bohm, with Nish Dubashia. Hamburg, Germany: Tredition

- 2020. David Bohm’s Critique of Modern Physics, Letters to Jeffrey Bub, 1966-1969, Foreword by Jeffrey Bub, editor Chris Talbot. Cham, Switzerland: Springer

- 미국 철학

- 봄 외피 기준(Bohm sheath criterion)

- 미국 철학자 명단(List of American philosophers)

- 오케스트레이션된 목표 감소(Orchestrated objective reduction)

- 칼 H. 프리브람Karl H. Pribram

- 양자 마음(Quantum mind)

- 양자 신비주의(Quantum mysticism)

- 랜덤 위상 근사(Random phase approximation)

- 홀로그램 우주

- ↑ 가 나 B. J. Hiley (1997). "David Joseph Bohm. 20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992: Elected F.R.S. 1990". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 43: 107–131.

- ↑ Peat 1997, pp. 316-317

- ↑ 가 나 David Bohm: Wholeness and the Implicate Order, Routledge, 1980

- ↑ 가 나 Comparison between Karl Pribram's "Holographic Brain Theory" and more conventional models of neuronal computation

- ↑ Wholeness and the Implicate Order, Bohm - 4 July 2002

- ↑ David Bohm: On Dialogue (2004) Routledge

- ↑ Becker, Adam (2018). What is Real?: The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics. Basic Books. p. 115.

- ↑ Freire Junior, Olival (2019). David Bohm:A Life Dedicated to Understanding the Quantum World. Springer. p. 37.

- ↑ http://ed.augie.edu/~wjdelfs/381bohm.htm Archived 2010년 7월 2일 - 웨이백 머신 [permanent dead link] - By the Numbers – David Bohm

- ↑ Peat 1997, p.21. "그가 유대인의 지식과 관습을 그의 아버지와 동일시했다면, 이것은 그가 사무엘과 거리를 두는 방법이었다. 10대 후반이 되자 그는 확고한 불가지론자가 되었다."

- ↑ Garber, Marjorie; Walkowitz, Rebecca (1995). Secret Agents: The Rosenberg Case, McCarthyism and Fifties America. New York: Routledge. pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Peat 1997, p. 64

- ↑ Russell Olwell: Physics and Politics in Cold War America: The Two Exiles of David Bohm, Working Paper Number 20. Program in Science, Technology, and Society. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ↑ Kumar, Manjit (24 May 2010). Quantum: Einstein, Bohr, and the Great Debate about the Nature of Reality.

- ↑ Albert Einstein to Patrick Blackett, 17 April 1951 (Albert Einstein archives). Cited after Olival Freire, Jr.: Science and Exile: David Bohm, the cold war, and a new interpretation of quantum mechanics Archived 2012년 3월 26일 - 웨이백 머신 HSPS, vol. 36, Part 1, pp. 1–34,

- ↑ Observing the Average Trajectories of Single Photons in a Two-Slit Interferometer.

- ↑ D. Bohm: The characteristics of electrical discharges in magnetic fields, in: A. Guthrie, R. K. Wakerling (eds.), McGraw–Hill, 1949.

- ↑ Maurice A. de Gosson, Basil J. Hiley: Zeno paradox for Bohmian trajectories: the unfolding of the metatron, 3 January 2011.

- ↑ B. J. Hiley: Some remarks on the evolution of Bohm's proposals for an alternative to quantum mechanics, 30 January 2010.

- ↑ David Bohm, Basil Hiley: The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory, edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-library 2009 (first edition Routledge, 1993), p. 2.

- ↑ Russell Olwell: Physics and politics in cold war America: the two exiles of David Bohm Working Paper Number 2, Working Program in Science, Technology, and Society; Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- ↑ 가 나 Olival Freire, Jr.: Science and Exile: David Bohm, the cold war, and a new interpretation of quantum mechanics Archived 2012년 3월 26일 - 웨이백 머신 vol. 36, Part 1, pp. 1–34, 2005.

- ↑ "Erwin Madelung 1881–1972". Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main. 12 December 2008.

- ↑ Pines, D; Bohm, D. A (1951). "Collective Description of Electron Interactions. I. Magnetic Interactions". Physical Review. 82 (5): 625–634. Bibcode:1951PhRv...82..625B.

- ↑ Pines, D; Bohm, D. A (1952). "Collective Description of Electron Interactions: II. Collective vs Individual Particle Aspects of the Interactions". Physical Review. 85 (2): 338–353. Bibcode:1952PhRv...85..338P.

- ↑ Pines, D; Bohm, D. (1953). "A Collective Description of Electron Interactions: III. Coulomb Interactions in a Degenerate Electron Gas". Physical Review. 92 (3): 609–626. Bibcode:1953PhRv...92..609B.

- ↑ Bohm, D.; Aharonov, Y. (15 November 1957). "Discussion of Experimental Proof for the Paradox of Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky". Physical Review. American Physical Society (APS). 108 (4): 1070–1076. Bibcode:1957PhRv..108.1070B.

- ↑ Bell, J.S. (1964). "On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox" (PDF). Physics Physique Fizika. 1 (3): 195–200.

- ↑ "collected papers".

- ↑ Bohm, David; Hiley, Basil J.; Stuart, Allan E. G. (1970). "On a new mode of description in physics". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 3 (3): 171–183. Bibcode:1970IJTP....3..171B.

- ↑ David Bohm, F. David Peat: Science, Order, and Creativity, 1987

- ↑ Basil J. Hiley: Process and the Implicate Order: their relevance to Quantum Theory and Mind. (PDF Archived 2011년 9월 26일 - 웨이백 머신)

- ↑ The holographic brain Archived 2006년 5월 18일 - 웨이백 머신 Archived 18 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine, with Karl Pribram

- ↑ Mary Lutyens (1983). "Freedom is Not Choice". Krishnamurti: The Years of Fulfillment. Krishnamurti Foundation Trust Ltd. p. 208.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 David Edmund Moody (2016). An Uncommon Collaboration: David Bohm and J. Krishnamurti[깨진 링크(과거 내용 찾기)]. Alpha Centauri Press.

- ↑ J. Krishnamurti (2000). Truth and Actuality. Krishnamurti Foundation Trust Ltd.

- ↑ J. Krishnamurti and D. Bohm (1985). The Ending of Time. HarperCollins.

- ↑ J. Krishnamurti and D. Bohm (1999). The Limits of Thought: Discussions between J. Krishnamurti and David Bohm. Routledge.

- ↑ F. David Peat (1997). Infinite Potential: The Life and Times of David Bohm. Basic Books.

- ↑ 가 나 Gardner, Martin (July 2000). "David Bohm and Jiddo Krishnamurti". Skeptical Inquirer.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 David Bohm (1994). Thought as a System. Psychology Press.

- ↑ David Bohm (12 October 2012). On Creativity. Routledge. p. 118.

- ↑ David Bohm; F. David Peat (25 February 2014). Science, Order and Creativity Second Edition. Routledge. pp. 204–.

- ↑ Peat 1997, p. 80

- ↑ Hiley, Basil; Peat, F. David, eds. (2012). Quantum Implications: Essays in Honour of David Bohm. Routledge. p. 443.

- ↑ Peat 1997, pp. 308-317

- ↑ Peat 1997, pp. 308-317

- ↑ Infinite potential: the life and times of David Bohm (film) www.infinitepotential.com

- ↑ Kožnjak, Boris (2017). "The missing history of Bohm's hidden variables theory: the Ninth Symposium of the Colston Research Society, Bristol, 1957". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics. 62: 85–97. Bibcode:2018SHPMP..62...85K.

- David Z. Albert (May 1994). "Bohm's Alternative to Quantum Mechanics". ‘’Scientific American‘’. 270 (5): 58. Bibcode:1994SciAm.270e..58A.

- Joye, S.R. (2017). ‘’The Little Book of Consciousness: Pribram's Holonomic Brain Theory and Bohm's Implicate Order‘’. The Viola Institute.

- Greeg Herken (2002). Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller. Holt. ISBN 0-8050-6589-X. (information on Bohm's work at Berkeley and his dealings with HUAC)

- F. David Peat (1997). Infinite Potential: the Life and Times of David Bohm. Addison Wesley.

- B.J. Hiley, F. David Peat, ed. (1987). Quantum Implications: Essays in Honour of David Bohm. Routledge.

- David Bohm; Sarah Bohm (1992). Thought as a System. Routledge. (transcript of seminar held in Ojai, California, from 30 November to 2 December 1990)

- Peter R. Holland (2000). The Quantum Theory of Motion: an account of the de Broglie-Bohm Causal Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Cambridge University Press.

- William Keepin: A life of dialogue between science and spirit – David Bohm. In World Scriptures: Leland P. Stewart (ed.): Guidelines for a Unity-and-Diversity Global Civilization, World Scriptures Vol. 2, AuthorHouse. (2009) pp. 5–13

- William Keepin: Lifework of David Bohm. River of Truth, Re-vision, vol. 16, no. 1, 1993, p. 32.

- The David Bohm Society

- The Bohm Krishnamurti Project: Exploring the Legacy of the David * * Bohm and Jiddu Krishnamurti Relationship

- David Bohm's ideas about Dialogue

- the David_Bohm_Hub. Includes compilations of David Bohm's life and work in form of texts, audio, video, and pictures

- Lifework of David Bohm: River of Truth Archived 2021년 1월 25일 - 웨이백 머신: Article by Will Keepin (PDF-version)

- Interview with David Bohm provided and conducted by F. David Peat along with John Briggs, first issued in Omni magazine, January 1987

- Archive of papers at Birkbeck College relating to David Bohm and David Bohm at the National Archives

- David Bohm at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm 8 May 1981 Archived 2015년 5월 31일 - 웨이백 머신, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

- 1979 Audio Interview with David Bohm by Martin Sherwin at Voices of the Manhattan Project

- The Bohm Documentary by David Peat and Paul Howard (in production)

- The Best David Bohm Interview about "The Nature of Things" by David Suzuki 26 May 1979

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 8 May 1981, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - interview conducted by Lillian Hoddeson in Edgware, London, England

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 6 June 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session I, interviews conducted by Maurice Wilkins

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 12 June 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session II

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 7 July 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session III

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 25 September 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session IV

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 3 October 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session V

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 22 December 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session VI

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 30 January 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session VII

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 7 February 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session VIII

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 27 February 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session IX

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 6 March 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session X

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 3 April 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session XI

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 16 April 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session XII