- It is only the act of contemplation when words and even personality are transcended, that the pure state of the Perennial Philosophy can actually be known.

- The records left by those who have known it in this way make it abundantly clear that all of them, whether Hindu, Buddhist, Hebrew, Taoist, Christian, or Mohammedan, were attempting to describe the same essentially indescribable Fact.

2024/03/18

Bhagavad Gita - The Song of God - Huxley Introduction 1

Bhagavad Gita - Wikipedia Intro 해설

Bhagavad Gita

| Bhagavad Gita | |

|---|---|

| |

| Information | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Author | Traditionally attributed to Vyasa |

| Language | Sanskrit |

| Chapters | 18 |

| Verses | 700 |

| Full text | |

The Bhagavad Gita (/ˌbʌɡəvəd ˈɡiːtɑː/; Sanskrit: भगवद्गीता, lit. '"God's Song"', IAST: bhagavad-gītā[a]), often referred to as the Gita (IAST: gītā), is a 700-verse Hindu scripture, which is part of the epic Mahabharata. It forms the chapters 23–40 of book 6 of the Mahabharata called the Bhishma Parva. The work is dated to the second half of the first millennium BCE.[2]

The Bhagavad Gita is set in a narrative framework of dialogue between the Pandava prince Arjuna and his charioteer guide Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu. At the start of the Kurukshetra War between the Pandavas and the Kauravas, Arjuna despairs thinking about the violence and death the war will cause in the battle against his kin and becomes emotionally preoccupied with a dilemma.[3] Wondering if he should renounce the war, Arjuna seeks the counsel of Krishna, whose answers and discourse constitute the Bhagavad Gita. Krishna counsels Arjuna to "fulfil his Kshatriya (warrior) duty" for the upholding of dharma.[4] The Krishna–Arjuna dialogue covers a broad range of spiritual topics, touching upon moral and ethical dilemmas, and philosophical issues that go far beyond the war that Arjuna faces.[1][5][6] The setting of the text in a battlefield has been interpreted as an allegory for the struggles of human life.

- Summarizing the Upanishadic conceptions of God,

- the Gita posits the existence of an individual self (Atman) and

- the supreme self (Brahman) within each being.[note 1]

The dialogue between the prince and his charioteer has been interpreted as a metaphor for an immortal dialogue between the human self and God.[note 2]

Commentators of Vedanta read varying notions in the Bhagavad Gita about the relationship between the Atman (individual Self) and Brahman (supreme Self);

Advaita Vedanta affirms on the non-dualism of Atman and Brahman,[7] Vishishtadvaita asserts qualified non-dualism with Atman and Brahman being related but different in certain aspects,

while Dvaita Vedanta declares the complete duality of Atman and Brahman.[note 3][6][8]

Per Hindu mythology, the Bhagavad Gita was written by the god Ganesha, as told to him by the sage Veda Vyasa.

The Bhagavad Gita presents a synthesis of various Hindu ideas about dharma, theistic bhakti, and the yogic ideal of moksha.[9][10]

The text covers Jñāna, Bhakti, Karma, and Rāja yogas,[9] while incorporating ideas from the Samkhya-Yoga philosophy.[web 1][note 4]

The Bhagavad Gita is one of the most revered Hindu scriptures,[12] and has a unique pan-Hindu influence.[13][14] It is a central text in the vaishnava tradition, and is part of the prasthanatrayi.

Numerous commentaries have been written on the Bhagavad Gita with differing views on its essence and essentials.

Etymology[edit]

The gita in the title of the Bhagavad Gita means "song of the god". Religious leaders and scholars interpret the word Bhagavad in a number of ways. Accordingly, the title has been interpreted as "the word of God" by the theistic schools,[15] "the words of the Lord",[16] "the Divine Song",[17][page needed][18] and "Celestial Song" by others.[19]

In India, its Sanskrit name is often written as Shrimad Bhagavad Gita, श्रीमद् भगवद् गीता (the latter two words often written as a single word भगवद्गीता), where the Shrimad prefix is used to denote a high degree of respect. The Bhagavad Gita is not to be confused with the Bhagavata Puran, which is one of the eighteen major Puranas dealing with the life of the Hindu God Krishna and various avatars of Vishnu.[20]

The work is also known as the Iswara Gita, the Ananta Gita, the Hari Gita, the Vyasa Gita, or the Gita.[21]

Date and authorship[edit]

Date[edit]

Theories on the date of the composition of the Gita vary considerably. Some scholars accept dates from the 5th century BCE to the 2nd century BCE as the probable range, the latter likely. The Hinduism scholar Jeaneane Fowler, in her commentary on the Gita, considers second century BCE to be the probable date of composition.[22] J. A. B. van Buitenen also states that the Gita was likely composed about 200 BCE.[23] According to the Indologist Arvind Sharma, the Gita is generally accepted to be a 2nd-century-BCE text.[24]

Kashi Nath Upadhyaya, in contrast, dates it a bit earlier. He states that the Gita was always a part of the Mahabharata, and dating the latter suffices in dating the Gita.[25] On the basis of the estimated dates of Mahabharata as evidenced by exact quotes of it in the Buddhist literature by Asvaghosa (c. 100 CE), Upadhyaya states that the Mahabharata, and therefore the Gita, must have been well known by then for a Buddhist to be quoting it.[25][note 5] This suggests a terminus ante quem (latest date) of the Gita to be sometime prior to the 1st century CE.[25] He cites similar quotes in the dharmasutra texts, the Brahma sutras, and other literature to conclude that the Bhagavad Gita was composed in the fifth or fourth century BCE.[27][note 6] According to Arthur Basham, the context of the Bhagavad Gita suggests that it was composed in an era when the ethics of war were being questioned and renunciation to monastic life was becoming popular.[29] Such an era emerged after the rise of Buddhism and Jainism in the 5th century BCE, and particularly after the semi-legendary life of Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE. Thus, the first version of the Bhagavad Gita may have been composed in or after the 3rd century BCE.[29]

Winthrop Sargeant linguistically categorizes the Bhagavad Gita as Epic-Puranic Sanskrit, a language that succeeds Vedic Sanskrit and precedes classical Sanskrit.[30] The text has occasional pre-classical elements of the Vedic Sanskrit language, such as aorists and the prohibitive mā instead of the expected na (not) of classical Sanskrit.[30] This suggests that the text was composed after the Pāṇini era, but before the long compounds of classical Sanskrit became the norm. This would date the text as transmitted by the oral tradition to the later centuries of the 1st-millennium BCE, and the first written version probably to the 2nd or 3rd century CE.[30][31] According to Jeaneane Fowler, "the dating of the Gita varies considerably" and depends in part on whether one accepts it to be a part of the early versions of the Mahabharata, or a text that was inserted into the epic at a later date.[32] The earliest "surviving" components therefore are believed to be no older than the earliest "external" references we have to the Mahabharata epic. The Mahabharata – the world's longest poem – is itself a text that was likely written and compiled over several hundred years, one dated between "400 BCE or little earlier, and 2nd century CE, though some claim a few parts can be put as late as 400 CE", states Fowler. The dating of the Gita is thus dependent on the uncertain dating of the Mahabharata. The actual dates of composition of the Gita remain unresolved.[32] While the year and century is uncertain, states Richard Davis,[33] the internal evidence in the text dates the origin of the Gita discourse to the Hindu lunar month of Margashirsha (also called Agrahayana, generally December or January of the Gregorian calendar).[34]

Authorship[edit]

In the Indian tradition, the Bhagavad Gita, as well as the epic Mahabharata of which it is a part, is attributed to the sage Vyasa,[35] whose full name was Krishna Dvaipayana, also called Veda-Vyasa.[36] Another Hindu legend states that Vyasa narrated it when the lord Ganesha broke one of his tusks and wrote down the Mahabharata along with the Bhagavad Gita.[37][38][note 7] Scholars consider Vyasa to be a mythical or symbolic author, in part because Vyasa is also the traditional compiler of the Vedas and the Puranas, texts dated to be from different millennia.[37][41][42] The word Vyasa literally means "arranger, compiler", and is a surname in India. According to Kashi Nath Upadhyaya, a Gita scholar, it is possible that a number of different individuals with the same name compiled different texts.[43]

Swami Vivekananda, the 19th-century Hindu monk and Vedantist, stated that the Bhagavad Gita may be old but it was mostly unknown in Indian history until the early 8th century when Adi Shankara (Shankaracharya) made it famous by writing his much-followed commentary on it.[44][45] Some infer, states Vivekananda, that "Shankaracharya was the author of Gita, and that it was he who foisted it into the body of the Mahabharata."[44] This attribution to Adi Shankara is unlikely in part because Shankara himself refers to the earlier commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita, and because other Hindu texts and traditions that compete with the ideas of Shankara refer to much older literature referencing the Bhagavad Gita, though much of this ancient secondary literature has not survived into the modern era.[44]

J. A. B. van Buitenen, an Indologist known for his translations and scholarship on Mahabharata, finds that the Gita is so contextually and philosophically well knit within the Mahabharata that it was not an independent text that "somehow wandered into the epic".[46] The Gita, states van Buitenen, was conceived and developed by the Mahabharata authors to "bring to a climax and solution the dharmic dilemma of a war".[46][note 8] According to Alexus McLeod, a scholar of Philosophy and Asian Studies, it is "impossible to link the Bhagavad Gita to a single author", and it may be the work of many authors.[37][49] This view is shared by the Indologist Arthur Basham, who states that there were three or more authors or compilers of Bhagavad Gita. This is evidenced by the discontinuous intermixing of philosophical verses with theistic or passionately theistic verses, according to Basham.[50][note 9]

Scriptural significance[edit]

The Bhagavad Gita is the best known[51] and most influential of Hindu scriptures.[12] While Hinduism is known for its diversity and the synthesis derived from it, the Bhagavad Gita holds a unique pan-Hindu influence.[13][52] Gerald James Larson – an Indologist and scholar of classical Hindu philosophy, states that "if there is any one text that comes near to embodying the totality of what it is to be a Hindu, it would be the Bhagavad Gita."[12][14] The Bhagavad Gita is part of the Prasthanatrayi, which also includes the Upanishads and the Brahma sutras. These three form the foundational texts of the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy.[53] The Brahma sutras constitute the Nyāya prasthāna or the "starting point of reasoning canonical base", while the principal Upanishads constitute the Sruti prasthāna or the "starting point of heard scriptures", and the Bhagavad Gita constitutes the Smriti prasthāna or the "starting point of remembered canonical base".[53] While Upanishads focuses more on knowledge and the identity of the self with Brahman, the Bhagavad Gita shifts the emphasis towards devotion and the worship of a personal deity, specifically Krishna.[54] The Bhagavad Gita forms a central text in the Vaishnava tradition,[55][56][57] and an important scripture in Hinduism.[58][59]

In Huston Smith's foreword for Sargeant's The Bhagavad Gita, he states that the Gita is a "summation of the Vedanta".[60] It is thus one of the key texts for the Vedanta,[61][62] a school of thought that provides one of the theoretical foundations for Hinduism,[63] and one that has had an enormous influence over time, becoming the central ideology of the Hindu renaissance in the 19th century, according to Gavin Flood – a scholar of Hinduism.[64][note 3] Some Hindus give it the status of an Upanishad, and some consider it to be a "revealed text".[65][66][67] There are alternate versions of the Bhagavad Gita (such as the one found in Kashmir), but the basic message behind these texts are not distorted.[68][69][70]

Hindu synthesis[edit]

The Bhagavad Gita is the sealing achievement of the Hindu synthesis, incorporating its various religious traditions.[10][11][9] The synthesis is at both philosophical and socio-religious levels, states the Gita scholar Keya Maitra.[71] The text refrains from insisting on one right marga (path) to spirituality. It openly synthesizes and inclusively accepts multiple ways of life, harmonizing spiritual pursuits through action (karma), knowledge (jñāna), and devotion (bhakti).[72] According to the Gita translator Radhakrishnan, quoted in a review by Robinson, Krishna's discourse is a "comprehensive synthesis" that inclusively unifies the competing strands of Hindu thought such as "Vedic ritual, Upanishadic wisdom, devotional theism and philosophical insight".[73] Aurobindo described the text as a synthesis of various Yogas. The Indologist Robert Minor, and others,[web 1] in contrast, state that the Gita is "more clearly defined as a synthesis of Vedanta, Yoga and Samkhya" philosophies of Hinduism.[74]

The synthesis in Bhagavad Gita addresses the question of what constitutes the virtuous path that is necessary for spiritual liberation or release from the cycles of rebirth (moksha).[75][76] It discusses whether one should renounce a householder lifestyle for a life as an ascetic, or lead a householder life dedicated to one's duty and profession, or pursue a householder life devoted to a personalized God in the revealed form of Krishna. Thus Gita discusses and synthesizes the three dominant trends in Hinduism: enlightenment-based renunciation, dharma-based householder life, and devotion-based theism. According to Deutsch and Dalvi, the Bhagavad Gita attempts "to forge a harmony" between these three paths.[9][note 10]

The Bhagavad Gita's synthetic answer recommends that one must resist the "either-or" view, and consider a "both-and" view.[77][78][79] It states that the dharmic householder can achieve the same goals as the renouncing monk through "inner renunciation" or "motiveless action".[75][note 11] One must do the right thing because one has determined that it is right, states Gita, without craving for its fruits, without worrying about the results, loss or gain.[81][82][83] Desires, selfishness, and the craving for fruits can distort one from spiritual living.[82] The Gita synthesis goes further, according to its interpreters such as Swami Vivekananda, and the text states that there is Living God in every human being and the devoted service to this Living God in everyone – without craving for personal rewards – is a means to spiritual development and liberation.[84][85][86] According to Galvin Flood, the teachings in the Gita differ from other Indian religions that encouraged extreme austerity and self-torture of various forms (karsayanta). The Gita disapproves of these, stating that not only is it against tradition but against Krishna himself, because "Krishna dwells within all beings, in torturing the body the ascetic would be torturing him", states Flood. Even a monk should strive for "inner renunciation" rather than external pretensions.[87]

The Gita synthesizes several paths to spiritual realization based on the premise that people are born with different temperaments and tendencies (guna).[88] Smith notes that the text acknowledges that some individuals are more reflective and intellectual, some affective and engaged by their emotions, some are action driven, yet others favor experimentation and exploring what works.[88] It then presents different spiritual paths for each personality type respectively: the path of knowledge (jnana yoga), the path of devotion (bhakti yoga), the path of action (karma yoga), and the path of meditation (raja yoga).[88][89] The guna premise is a synthesis of the ideas from the Samkhya school of Hinduism. According to Upadhyaya, the Gita states that none of these paths to spiritual realization is "intrinsically superior or inferior", rather they "converge in one and lead to the same goal".[90]

According to Hiltebeitel, Bhakti forms an essential ingredient of this synthesis, and the text incorporates Bhakti into Vedanta.[91] According to Scheepers, The Bhagavad Gita is a Brahmanical text which uses Shramanic and Yogic terminology to spread the Brahmanic idea of living according to one's duty or dharma, in contrast to the ascetic ideal of liberation by avoiding all karma.[92] According to Galvin Flood and Charles Martin, the Gita rejects the Shramanic path of non-action, emphasizing instead "the renunciation of the fruits of action".[93] The Bhagavad Gita, according to Raju, is a great synthesis of impersonal spiritual monism with personal God, of "the yoga of action with the yoga of transcendence of action, and these again with the yogas of devotion and knowledge".[11]

Manuscripts and layout[edit]

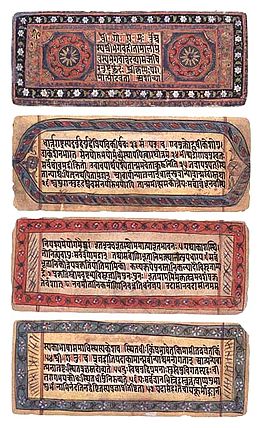

The Bhagavad Gita manuscript is found in the sixth book of the Mahabharata manuscripts – the Bhisma-parvan. Therein, in the third section, the Gita forms chapters 23–40, that is 6.3.23 to 6.3.40.[94] The Bhagavad Gita is often preserved and studied on its own, as an independent text with its chapters renumbered from 1 to 18.[94] The Bhagavad Gita manuscripts exist in numerous Indic scripts.[95] These include writing systems that are currently in use, as well as early scripts such as the now dormant Sharada script.[95][96] Variant manuscripts of the Gita have been found on the Indian subcontinent[68][97] Unlike the enormous variations in the remaining sections of the surviving Mahabharata manuscripts, the Gita manuscripts show only minor variations.[68][97]

According to Gambhirananda, the old manuscripts may have had 745 verses, though he agrees that “700 verses is the generally accepted historic standard."[98] Gambhirananda's view is supported by a few versions of chapter 6.43 of the Mahabharata. According to Gita exegesis scholar Robert Minor, these versions state that the Gita is a text where "Kesava [Krishna] spoke 574 slokas, Arjuna 84, Sanjaya 41, and Dhritarashtra 1".[99] An authentic manuscript of the Gita with 745 verses has not been found.[100] Adi Shankara, in his 8th-century commentary, explicitly states that the Gita has 700 verses, which was likely a deliberate declaration to prevent further insertions and changes to the Gita. Since Shankara's time, "700 verses" has been the standard benchmark for the critical edition of the Bhagavad Gita.[100]

Structure[edit]

The Bhagavad Gita is a poem written in the Sanskrit language.[101] Its 700 verses[97] are structured into several ancient Indian poetic meters, with the principal being the shloka (Anushtubh chanda). It has 18 chapters in total.[102] Each shloka consists of a couplet, thus the entire text consists of 1,400 lines. Each shloka has two quarter verses with exactly eight syllables. Each of these quarters is further arranged into two metrical feet of four syllables each.[101][note 12] The metered verse does not rhyme.[103] While the shloka is the principal meter in the Gita, it does deploy other elements of Sanskrit prosody (which refers to one of the six Vedangas, or limbs of Vedic statues).[104] At dramatic moments, it uses the tristubh meter found in the Vedas, where each line of the couplet has two quarter verses with exactly eleven syllables.[103]

Characters[edit]

- Arjuna, one of the five Pandavas

- Krishna, Arjuna's charioteer and guru who was actually an incarnation of Vishnu

- Sanjaya, counselor of the Kuru king Dhritarashtra (secondary narrator)

- Dhritarashtra, Kuru king (Sanjaya's audience) and father of the Kauravas

Narrative[edit]

The Gita is a dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna right before the start of the climactic Kurukshetra War in the Hindu epic Mahabharata.[105][note 13] Two massive armies have gathered to destroy each other. The Pandava prince Arjuna asks his charioteer Krishna to drive to the center of the battlefield so that he can get a good look at both the armies and all those "so eager for war".[107] He sees that some among his enemies are his own relatives, beloved friends, and revered teachers. He does not want to fight to kill them and is thus filled with doubt and despair on the battlefield.[108] He drops his bow, wonders if he should renounce and just leave the battlefield.[107] He turns to his charioteer and guide Krishna, for advice on the rationale for war, his choices and the right thing to do. The Bhagavad Gita is the compilation of Arjuna's questions and moral dilemma and Krishna's answers and insights that elaborate on a variety of philosophical concepts.[107][109]

The compiled dialogue goes far beyond the "rationale for war"; it touches on many human ethical dilemmas, philosophical issues and life's choices.[107] According to Flood and Martin, although the Gita is set in the context of a wartime epic, the narrative is structured to apply to all situations; it wrestles with questions about "who we are, how we should live our lives, and how should we act in the world".[110] According to Sargeant, it delves into questions about the "purpose of life, crisis of self-identity, human Self, human temperaments, and ways for spiritual quest".[6]

The Gita posits the existence of two selfs in an individual,[note 1] and its presentation of Krishna-Arjuna dialogue has been interpreted as a metaphor for an eternal dialogue between the two.[note 2]

Chapters and content[edit]

Bhagavad Gita comprises 18 chapters (section 23 to 40)[113][web 4] in the Bhishma Parva of the epic Mahabharata. Because of differences in recensions, the verses of the Gita may be numbered in the full text of the Mahabharata as chapters 6.25–42 or as chapters 6.23–40.[web 5] The number of verses in each chapter vary in some manuscripts of the Gita discovered on the Indian subcontinent. However, variant readings are relatively few in contrast to the numerous versions of the Mahabharata it is found embedded in.[97]

The original Bhagavad Gita has no chapter titles. Some Sanskrit editions that separate the Gita from the epic as an independent text, as well as translators, however, add chapter titles.[114][web 5] For example, Swami Chidbhavananda describes each of the eighteen chapters as a separate yoga because each chapter, like yoga, "trains the body and the mind". He labels the first chapter "Arjuna Vishada Yogam" or the "Yoga of Arjuna's Dejection".[115] Sir Edwin Arnold titled this chapter in his 1885 translation as "The Distress of Arjuna".[16][note 14]

Chapter listing[edit]

There are total 18 chapters and 700 verses in Gita. These are:

| Chapter | Name of Chapter | Total Verses |

| 1 | Arjuna Vishada Yoga | 47 |

| 2 | Sankhya Yoga | 72 |

| 3 | Karma Yoga | 43 |

| 4 | Gyana-Karma-Sanyasa Yoga | 42 |

| 5 | Karma-Sanyasa Yoga | 29 |

| 6 | Atma-Samyama Yoga (Dhyana Yoga) | 47 |

| 7 | Gyana-Vigyana Yoga | 30 |

| 8 | Akshara Brahma Yoga | 28 |

| 9 | Raja-Vidya-Raja-Guhya Yoga | 34 |

| 10 | Vibhuti Yoga | 42 |

| 11 | Vishwarupa-Darsana Yoga | 55 |

| 12 | Bhakti Yoga | 20 |

| 13 | Ksetra-Ksetrajna-Vibhaga Yoga | 34 |

| 14 | Gunatraya-Vibhaga Yoga | 27 |

| 15 | Purushottama Yoga | 20 |

| 16 | Daivasura-Sampad-Vibhaga Yoga | 24 |

| 17 | Shraddha-Traya-Vibhaga Yoga | 28 |

| 18 | Moksha-Sanyasa Yoga | 78 |

| Total | 700 |

Chapter 1: Arjuna Vishada Yoga (47 verses)[edit]

Translators have variously titled the first chapter as Arjuna Vishada-yoga, Prathama Adhyaya, The Distress of Arjuna, The War Within, or Arjuna's Sorrow.[16][118][119] The Bhagavad Gita is opened by setting the stage of the Kurukshetra battlefield. Two massive armies representing different loyalties and ideologies face a catastrophic war. With Arjuna is Krishna, not as a participant in the war, but only as his charioteer and counsel. Arjuna requests Krishna to move the chariot between the two armies so he can see those "eager for this war". He sees family and friends on the enemy side. Arjuna is distressed and in sorrow.[120] The issue is, states Arvind Sharma, "is it morally proper to kill?"[121] This and other moral dilemmas in the first chapter are set in a context where the Hindu epic and Krishna have already extolled ahimsa (non-violence) to be the highest and divine virtue of a human being.[121] The war feels evil to Arjuna and he questions the morality of war. He wonders if it is noble to renounce and leave before the violence starts, or should he fight, and why.[120]

Chapter 2: Sankhya Yoga (72 verses)[edit]

Deeds without Expections of the Result

॥ कर्मण्येवाधिकारस्ते मा फलेषु कदाचन ।

मा कर्मफलहेतुर्भुर्मा ते सङ्गोऽस्त्वाकर्मणि॥One has the right to perform their expected duty,

But not to the right to the fruits of action;

One should not consider oneself as the doer of the action,

Nor should one attach oneself to inaction.- Bhagavad Gita 2 : 47

Translators title the chapter as Sankhya Yoga, The Book of Doctrines, Self-Realization, or The Yoga of Knowledge (and Philosophy).[16][118][119] The second chapter begins the philosophical discussions and teachings found in the Gita. The warrior Arjuna whose past had focused on learning the skills of his profession now faces a war he has doubts about. Filled with introspection and questions about the meaning and purpose of life, he asks Krishna about the nature of life, Self, death, afterlife and whether there is a deeper meaning and reality.[122] Krishna teaches Arjuna about the eternal nature of the soul (atman) and the temporary nature of the body, advising him to perform his warrior duty with detachment and without grief. The chapter summarizes the Hindu idea of rebirth, samsara, eternal Self in each person (Self), universal Self present in everyone, various types of yoga, divinity within, the nature of knowledge of the Self and other concepts.[122] The ideas and concepts in the second chapter reflect the framework of the Samkhya and Yoga schools of Hindu philosophy. This chapter is an overview for the remaining sixteen chapters of the Bhagavad Gita.[122][123][124] Mahatma Gandhi memorized the last 19 verses of the second chapter, considering them as his companion in his non-violent movement for social justice during colonial rule.[125]

Chapter 3: Karma Yoga (43 verses)[edit]

Translators title the chapter as Karma yoga, Virtue in Work, Selfless Service, or The Yoga of Action.[16][118][119] After listening to Krishna's spiritual teachings in Chapter 2, Arjuna gets more confounded and returns to the predicament he faces. He wonders if fighting the war is "not so important after all" given Krishna's overview on the pursuit of spiritual wisdom. Krishna replies that there is no way to avoid action (karma), since abstention from work is also an action.[126] Krishna states that Arjuna has an obligation to understand and perform his duty (dharma), because everything is connected by the law of cause and effect. Every man or woman is bound by activity. Those who act selfishly create the Karmic cause and are thereby bound to the effect which may be good or bad.[126] Those who act selflessly for the right cause and strive to do their dharmic duty are doing God's work.[126] Those who act without craving for fruits are free from the Karmic effects because the results never motivate them. Whatever the result, it does not affect them. Their happiness comes from within, and the external world does not bother them.[126][127] According to Flood and Martin, chapter 3 and onwards develops "a theological response to Arjuna's dilemma".[128]

Chapter 4: Gyana Karma Sanyasa Yoga (42 verses)[edit]

Translators title the fourth chapter as Jñāna–Karma-Sanyasa yoga, The Religion of Knowledge, Wisdom in Action, or The Yoga of Renunciation of Action through Knowledge.[16][118][119] Krishna reveals that he has taught this yoga to the Vedic sages. Arjuna questions how Krishna could do this, when those sages lived so long ago, and Krishna was born more recently. Krishna reminds him that everyone is in the cycle of rebirths, and while Arjuna does not remember his previous births, he does. Whenever dharma declines and the purpose of life is forgotten by Man, says Krishna, he returns to re-establish dharma.[note 15] Every time he returns, he teaches about the inner Self in all beings. The later verses of the chapter return to the discussion of motiveless action and the need to determine the right action, performing it as one's dharma (duty) while renouncing the results, rewards, fruits. The simultaneous outer action with inner renunciation, states Krishna, is the secret to the life of freedom. Action leads to knowledge, while selfless action leads to spiritual awareness, state the last verses of this chapter.[4] The 4th chapter is the first time where Krishna begins to reveal his divine nature to Arjuna.[129][130]

Chapter 5: Karma Sanyasa Yoga (29 verses)[edit]

Translators title this chapter as Karma–Sanyasa yoga, Religion by Renouncing Fruits of Works, Renounce and Rejoice, or The Yoga of Renunciation.[16][118][119] The chapter starts by presenting the tension in the Indian tradition between the life of sannyasa (monks who have renounced their household and worldly attachments) and the life of grihastha (householder). Arjuna asks Krishna which path is better.[131] Krishna answers that both are paths to the same goal, but the path of "selfless action and service" with inner renunciation is better. The different paths, says Krishna, aim for—and if properly pursued, lead to—Self-knowledge. This knowledge leads to the universal, transcendent Godhead, the divine essence in all beings, to Brahman – to Krishna himself. The final verses of the chapter state that the self-aware who have reached self-realization live without fear, anger, or desire. They are free within, always.[132][133] Chapter 5 shows signs of interpolations and internal contradictions. For example, states Arthur Basham, verses 5.23–28 state that a sage's spiritual goal is to realize the impersonal Brahman, yet the next verse 5.29 states that the goal is to realize the personal God who is Krishna.[50]

It is not those who lack energy

nor those who refrain from action,

but those who work without expecting reward

who attain the goal of meditation,

Theirs is true renunciation(sanyāsā).

Chapter 6: Dhyana Yoga (Aatma Samyam Yoga) (47 verses)[edit]

Translators title the sixth chapter as Dhyana yoga, Religion by Self-Restraint, The Practice of Meditation, or The Yoga of Meditation.[16][118][119] The chapter opens as a continuation of Krishna's teachings about selfless work and the personality of someone who has renounced the fruits that are found in chapter 5. Krishna says that such self-realized people are impartial to friends and enemies, are beyond good and evil, equally disposed to those who support them or oppose them because they have reached the summit of consciousness. The verses 6.10 and after proceed to summarize the principles of Yoga and meditation in the format similar to but simpler than Patanjali's Yogasutra. It discusses who is a true yogi, and what it takes to reach the state where one harbors no malice towards anyone.[140][141] Verse 6.47 emphasizes the significance of soul's faith and loving service to Krishna as the highest form of yoga.[142]

Chapter 7: Gyana Vigyana Yoga (30 verses)[edit]

Translators title this chapter as Jnana–Vijnana yoga, Religion by Discernment, Wisdom from Realization, or The Yoga of Knowledge and Judgment.[16][118][119] The seventh chapter opens with Krishna continuing his discourse. He discusses jnana (knowledge) and vijnana (realization, understanding) using the Prakriti-Purusha (matter-Self) framework of the Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy, and the Maya-Brahman framework of the Vedanta school. The chapter states that evil is the consequence of ignorance and attachment to the impermanent, the elusive Maya. Maya is described as difficult to overcome, but those who rely on Krishna can easily cross beyond Maya and attain moksha. It states that Self-knowledge and union with Purusha (Krishna) are the highest goal of any spiritual pursuit.[143]

Chapter 8: Akshara Brahma Yoga (28 verses)[edit]

Translators title the chapter as Aksara–Brahma yoga, Religion by Devotion to the One Supreme God, The Eternal Godhead, or The Yoga of the Imperishable Brahman.[16][118][119] The chapter opens with Arjuna asking questions such as what is Brahman and what is the nature of karma. Krishna states that his own highest nature is the imperishable Brahman, and that he lives in every creature as the adhyatman. Every being has an impermanent body and an eternal Self, and that "Krishna as Lord" lives within every creature. The chapter discusses cosmology, the nature of death and rebirth.[144] This chapter contains eschatology of the Bhagavad Gita. Importance of the last thought before death, differences between material and spiritual worlds, and light and dark paths that a Self takes after death are described.[144] Krishna advises Arjuna about focusing the mind on the Supreme Deity within the heart through yoga, including pranayama and chanting sacred mantra "Om" to ensure concentration on Krishna at the time of death.[145]

Chapter 9: Raja Vidya Raja Guhya Yoga (34 verses)[edit]

Translators title the ninth chapter as Raja–Vidya–Raja–Guhya yoga, Religion by the Kingly Knowledge and the Kingly Mystery, The Royal Path, or The Yoga of Sovereign Science and Sovereign Secret.[16][118][119] Chapter 9 opens with Krishna continuing his discourse as Arjuna listens. Krishna states that he is everywhere and in everything in an unmanifested form, yet he is not in any way limited by them. Eons end, everything dissolves and then he recreates another eon subjecting them to the laws of Prakriti (nature).[146] He equates himself to being the father and the mother of the universe, to being the Om, to the three Vedas, to the seed, the goal of life, the refuge and abode of all. The chapter recommends devotional worship of Krishna.[146] According to theologian Christopher Southgate, verses of this chapter of the Gita are panentheistic,[147] while German physicist and philosopher Max Bernhard Weinstein deems the work pandeistic.[148] It may, in fact, be neither of them, and its contents may have no definition with previously developed Western terms.

Chapter 10: Vibhuti Yoga (42 verses)[edit]

Translators title the chapter as Vibhuti–Vistara–yoga, Religion by the Heavenly Perfections, Divine Splendor, or The Yoga of Divine Manifestations.[16][118][119] When Arjuna asks of the opulences (Vibhuti) of Krishna, he explains how all the entities are his forms. He reveals his divine being in greater detail as the ultimate cause of all material and spiritual existence, as one who transcends all opposites and who is beyond any duality. Nevertheless, at Arjuna's behest, Krishna states that the following are his major opulences: He is the atman in all beings, Arjuna's innermost Self, the compassionate Vishnu, Surya, Indra, Shiva-Rudra, Ananta, Yama, as well as the Om, Vedic sages, time, Gayatri mantra, and the science of Self-knowledge. Krishna says, "Among the Pandavas, I am Arjuna," implying he is manifest in all the beings, including Arjuna. He also says that he is Rama when he says, "Among the wielders of weapons, I am Rama". Arjuna accepts Krishna as the purushottama (Supreme Being).[149]

Chapter 11: Vishvarupa Darshana Yoga (55 verses)[edit]

Translators title the chapter as Vishvarupa–Darshana yoga, The Manifesting of the One and Manifold, The Cosmic Vision, or The Yoga of the Vision of the Cosmic Form.[16][118][119] On Arjuna's request, Krishna displays his "universal form" (Viśvarūpa).[150] Arjuna asks Krishna to see the Eternal with his own eyes. The Krishna then "gives" him a "heavenly" eye so that he can recognize the All-Form Vishvarupa of the Supreme God Vishnu or Krishna. Arjuna sees the divine form, with his face turned all around, as if the light of a thousand suns suddenly burst forth in the sky. And he sees neither end, middle nor beginning. And he sees the gods and the host of beings contained within him. He also sees the Lord of the gods and the universe as the Lord of time, who devours his creatures in his "maw". And he sees people rushing to their doom in haste. And the Exalted One says that even the fighters are all doomed to death. And he, Arjuna, is his instrument to kill those who are already "killed" by him. Arjuna folds his hands trembling and worships the Most High. This is an idea found in the Rigveda and many later Hindu texts, where it is a symbolism for atman (Self) and Brahman (Absolute Reality) eternally pervading all beings and all existence.[151][152] Chapter 11, states Eknath Eswaran, describes Arjuna entering first into savikalpa samadhi (a particular form), and then nirvikalpa samadhi (a universal form) as he gets an understanding of Krishna. A part of the verse from this chapter was recited by J. Robert Oppenheimer in a 1965 television documentary about the atomic bomb.[150]

Chapter 12: Bhakti Yoga (20 verses)[edit]

Translators title this chapter as Bhakti yoga, The Religion of Faith, The Way of Love, or The Yoga of Devotion.[16][118][119] In this chapter, Krishna glorifies the path of love and devotion to God. Krishna describes the process of devotional service (Bhakti yoga). Translator Eknath Easwaran contrasts this "way of love" with the "path of knowledge" stressed by the Upanishads, saying that "when God is loved in [a] personal aspect, the way is vastly easier". He can be projected as "a merciful father, a divine mother, a wise friend, a passionate beloved, or even a mischievous child".[153] The text states that combining "action with inner renunciation" with the love of Krishna as a personal God leads to peace. In the last eight verses of this chapter, Krishna states that he loves those who have compassion for all living beings, are content with whatever comes their way, and live a detached life that is impartial and selfless, unaffected by fleeting pleasure or pain, neither craving for praise nor depressed by criticism.[153][154]

Chapter 13: Kshetra Kshetragya Vibhaga Yoga (34 verses)[edit]

Translators title this chapter as Ksetra–Ksetrajna Vibhaga yoga, Religion by Separation of Matter and Spirit, The Field and the Knower, or The Yoga of Difference between the Field and Field-Knower.[16][118][119] The chapter opens with Krishna continuing his discourse. He describes the difference between the transient perishable physical body (kshetra) and the immutable eternal Self (kshetrajna). The presentation explains the difference between ahamkara (ego) and atman (Self), from there between individual consciousness and universal consciousness. The knowledge of one's true self is linked to the realization of the Self.[155][156] The 13th chapter of the Gita offers the clearest enunciation of the Samkhya philosophy, states Basham, by explaining the difference between field (material world) and the knower (Self), prakriti and purusha.[157] According to Miller, this is the chapter which "redefines the battlefield as the human body, the material realm in which one struggles to know oneself" where human dilemmas are presented as a "symbolic field of interior warfare".[158]

Chapter 14: Gunatraya Vibhaga Yoga (27 verses)[edit]

Translators title the fourteenth chapter as Gunatraya–Vibhaga yoga, Religion by Separation from the Qualities, The Forces of Evolution, or The Yoga of the Division of Three Gunas.[16][118][119] Krishna continues his discourse from the previous chapter. Krishna explains the difference between purusha and prakriti, by mapping human experiences to three Guṇas (tendencies, qualities).[159] These are listed as sattva, rajas and tamas. All thoughts, words and actions are filled with sattva (truthfulness, purity, clarity), rajas (movement, energy, passion) or tamas (darkness, inertia, stability). Whoever understands everything that exists as the interaction of these three states of being can gain knowledge. When asked by Arjuna how he recognizes the one who has conquered the three gunas, Krishna replies: He who remains calm and composed when a guna 'arises', who always maintains equanimity, who is steadfast in joy and sorrow, who remains the same when he is reviled or admired, who renounces every action (from the ego), detaches himself from the power of the gunas. Likewise, the one who seeks me with unwavering love succeeds in doing so. He too transcends the three gunas and can become one with Brahman. All phenomena and individual personalities are thus a combination of all three gunas in varying and ever-changing proportions. The gunas affect the ego, but not the Self, according to the text.[159] This chapter also relies on Samkhya theories.[160][161][162]

Chapter 15: Purushottama Yoga (20 verses)[edit]

Translators title the chapter as Purushottama yoga, Religion by Attaining the Supreme Krishna, The Supreme Self, or The Yoga of the Supreme Purusha.[16][118][119] The fifteenth chapter expounds on Krishna's theology, in the Vaishnava Bhakti tradition of Hinduism. Krishna discusses the nature of God, according to Easwaran, wherein Krishna not only transcends the impermanent body (matter) but also transcends the atman (Self) in every being.[163] It follows an image of an upside tree with roots in the sky, without beginning and without end. It is necessary to cut down its shoots (sense objects), branches and the solid root with the axe of equanimity and "non-attachment" and thereby reach the immovable spirit (Brahman). Later it is said that the supreme Self (Purushottama) is greater than this immutable mind (akshara) and also greater than the mind that became things (kshara). He is the one who carries this entire threefold world and who, as Lord, governs and encompasses it. Whoever truly recognizes this has reached the ultimate goal. According to Franklin Edgerton, the verses in this chapter, in association with select verses in other chapters, make the metaphysics of the Gita to be dualistic. However, its overall thesis, according to Edgerton, is more complex because other verses teach the Upanishadic doctrines and "through its God the Gita seems after all to arrive at an ultimate monism; the essential part, the fundamental element, in every thing, is after all One — is God."[164]

Chapter 16: Daivasura Sampad Vibhaga Yoga (24 verses)[edit]

Translators title the chapter as Daivasura–Sampad–Vibhaga yoga, The Separateness of the Divine and Undivine, Two Paths, or The Yoga of the Division between the Divine and the Demonic.[16][118][119] According to Easwaran, this is an unusual chapter where two types of human nature are expounded, one leading to happiness and the other to suffering. Krishna identifies these human traits to be divine and demonic respectively. He states that truthfulness, self-restraint, sincerity, love for others, desire to serve others, being detached, avoiding anger, avoiding harm to all living creatures, fairness, compassion and patience are marks of the divine nature. The opposite of these are demonic, such as cruelty, conceit, hypocrisy and being inhumane, states Krishna.[165][166][167] Some of the verses in Chapter 16 may be polemics directed against competing Indian religions, according to Basham.[29] The competing tradition may be the materialists (Charvaka), states Fowler.[167]

Chapter 17: Shraddhatraya Vibhaga Yoga (28 verses)[edit]

Translators title the chapter as Shraddhatraya-Vibhaga yoga, Religion by the Threefold Kinds of Faith, The Power of Faith, or The Yoga of the Threefold Faith.[16][118][119] Krishna qualifies various aspects of human life, including faith, thoughts, deeds, and eating habits, in relation to the three gunas (modes): sattva (goodness), rajas (passion), and tamas (ignorance). Krishna explains how these modes influence different aspects of human behavior and spirituality, how one can align with the mode of goodness to advance on their spiritual journey. The final verse of the Chapter stresses that genuine faith (shraddha) is essential for spiritual growth. Actions without faith are meaningless, both in the material and spiritual realms, highlighting the significance of faith in one's spiritual journey.[168]

Chapter 18: Moksha Sanyasa Yoga (78 verses)[edit]

Translators title the chapter as Moksha–Sanyasa yoga, Religion by Deliverance and Renunciation, Freedom and Renunciation, or The Yoga of Liberation and Renunciation.[16][118][119] In the final and longest chapter, the Gita offers a final summary of its teachings in the previous chapters.[169] It gives a comprehensive overview of Bhagavad Gita's teachings, highlighting self-realization, duty, and surrender to Krishna to attain liberation and inner peace.[170] It begins with the discussion of spiritual pursuits through sannyasa (renunciation, monastic life) and spiritual pursuits while living in the world as a householder. It teaches "karma-phala-tyaga" (renunciation of the fruits of actions), emphasizing the renunciation of attachment to the outcomes of actions and performing duties with selflessness and devotion.[171]