On The Aesthetic Thought In Linquan Gaozhi

Posted on:2009-11-05 Degree:Master Type:Thesis

Country:China Candidate:Y Yan Full Text:PDF

GTID:2155360245494571 Subject:Literature and art

Abstract/Summary:

PDF Full Text Request

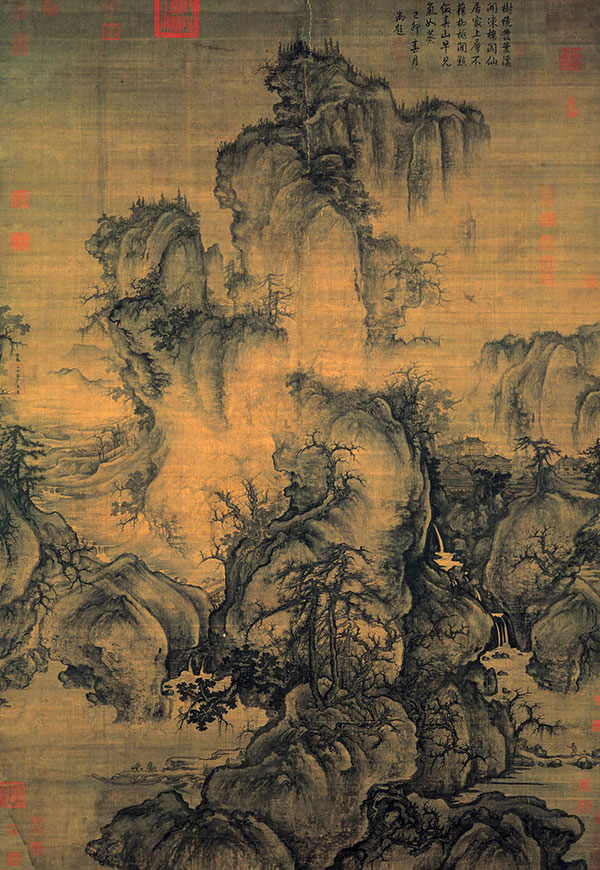

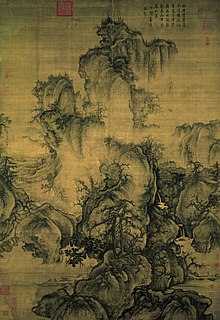

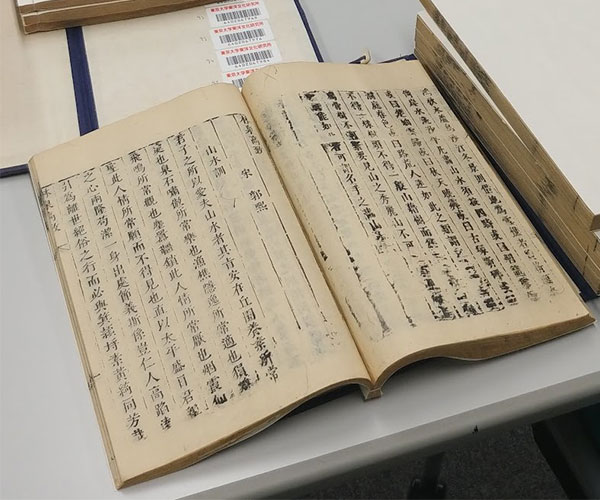

PDF Full Text RequestGuo Xi, an outstanding painter and painting theorist of Song Dynasty, is titled "the three greatest landscape painters of Northern Song Dynasty" together with Li Cheng and Fan Kuan. Guo Xi's lifelong creation experience, art view, and aesthetic thought were compiled into Linquan Gaozhi by his son Guo Si. A series of his important aesthetic thoughts in this work as "enjoying the nature close", "attainment of spirit and painting", and "three distances" had a profound influence on the aftertime development of aesthetic thoughts.Based on Linquan Gaozhi and some relevant literature and paintings, this thesis makes a deep probe into its aesthetic thought in the context of the political, economical, and cultural life of Northern Song Dynasty with the methods of social investigation, literature analysis, and picture analysis. This thesis holds that concern for human, especially concern for human's mind, is the starting point of Guo Xi's painting aesthetic thought, and also its final destination. First of all, in Linquan Gaozhi, Guo Xi puts forward "the original intention of landscape painting" is to build a spiritual Eden for the busy people, bringing them relaxation and tranquility. Secondly, the "true landscape" in Guo Xi's mind is the living landscape with inner life spirit. "Enjoying the nature close", which is proposed by him, is regarded as painters' general guideline of viewing the nature. Its key meaning is that painters should devote themselves into the nature and become part of the nature. Thirdly, he brings forward "attainment of spirit and painting", the highest level of creation, stressing painters should attach great importance to not only their cultural and artistic cultivation but also their psychological cultivation. Only by this, they can accomplish the fusion of heart and the outer world, and the fusion of spirit and paintings. Fourthly, Guo Xi proposed "three distances", which became not only an art goal pursued by Chinese landscape paintings, but also a spiritual goal. The "distance" in pictures draws man's eyes to the distance, and also brings people's mind to the state of pure tranquility, reaching the spiritual peace. Therefore, "distance" is the spiritual orientation of Guo Xi's landscape painting creation. Furthermore, this thesis makes a series of investigations into Guo Xi's life experience, growing background, artistic activities, artistic works as well as the compiler, different versions and modern aesthetic value of Linquan Gaozhi.

Keywords/Search Tags: Guo Xi, Linquan Gaozhi, aesthetic thought, spiritual landscape, spiritual Eden

PDF Full Text Request

PDF Full Text RequestRelated items

1 Research On Practical Value Of Linquan Gaozhi

2 Interpretation Of Spiritual Imbalance In Hard Times From The Perspective Of Spiritual Ecology Theory

3 On Guo Xi's "Linquan Gaozhi" And The Creation Of Landscape Painting

4 A Spiritual Ecological Interpretation Of The Protagonist In G.

5 Concerning The Spiritual Implication Sketch Watercolour Scenery

6 Widely Taken Casino, A Highly Personal Style

7 An Analysis Of The Spiritual Imbalance In All The Light We Cannot See From The Perspective Of Lu Shuyuan's Spiritual Ecology

8 Situation Analysis Of Contemporary Chinese People’s Spiritual Life

9 Returns The Break Point Inheritance And Development

10 Feeling The Spiritual Of The Masters

By Maromitsu Tsukamoto

By Maromitsu Tsukamoto Guo Si

Guo Si