48542737.pdf

A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF CHOAN-SENG SONG'S ...

A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT

OF CHOAN-SENG SONG'S EFFORT in

CONSTRUCTEVG CONTEXTUAL THEOLOGY

core.ac.uk

https://core.ac.uk › download › pdf

-----

A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF CHOAN-SENG SONG'S EFFORT in CONSTRUCTING CONTEXTUAL THEOLOGY

By

YEUNG KWOK KEUNG

SUPERVISOR DR. ARCHIE C. C. LEE

A THESIS m PARTIAL FULFILnv,fENT

OF REQUIRENfENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DIVINITY

4.

DIVISION OF RELIGION AND TÆOLOGY

GRADUATE SCHOOL

CHINESE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG

JUNE 1995.

AN ABSTRACT

This dissertation aims to provide a critical assessment of Choan-seng Song's effort in constructing contextual theology, In the first place, the recent discussions in contextual theology is outlined as a background for the discussions follow. The factors, both external and internal that leads to the rise of the consciousness in doing contextual theology are pointed out. Afterwards, the different models of contextual theology were looked at. These models vary in their different proportions of emphasis putting on the local culture and the Christian tradition. Different Asian theologies, including Song's, actually falls in different theological models sketched. Secondly, Song's conception of theology is delineated. He maintains that the traditional way of theologization is and was unsuitable for Asia, since it completely misunderstood not only Asian cultures, but the very concept of culture. He has made efforts in explicating the notion of culture as well as his understanding of images and symbols, which are the very manifestation of Asian cultures. We note that Song's conception of Asian theology is a direct implication of his conception of cultures. Song also proposes the new way of constructing local theology in Asia : 'doing theology with Asian resources'. The raw material for and context of doing theology, the meaning of the 'Asianness' of Asian theologies, new orientation in doing theology, and the method of doing theology by telling stories are then discussed. Lastly, a critical assessment of Song's effort in constructing local theology is made. We see that although Song admits the presupposition in any understanding including the theological one, he never reflects critically on his own presupposition and seems to neglect the great difference between his own situatedness and that of other Asians. This negligence pses him to regard himself erroneously as located in the vaguely delineated 'Asian' tradition. Then, by emphasizing the dialectical relationship of the two moments of interpretation, explanation and understanding, we consider Song's interpretation of texts as not rigorous enough. Concerning the general notion Of culture and the narrower scope of Asian cultures appear in Song's works, we find that he assumes a too private notion of cultural symbols. Moreover, he pays little attention to the reproductive constraints imposed by culture on human agents and grants the latter a too active and free role to play. This far too romantic view causes him to neglect, whether consciously or unconsciously, the Cdemonic' possibility Of 'the people' Although we appreciate the pluralist view of culture advocated by Song, we find that his stance is not consistent, for while he acknowledges the plural nature of Asian cultures, he does not pay much attention to more industrialized Asian cultures. We try to demonstrate, with a substantiation of a in-depth study of Hong Kong culture, that his rejection of the latter is a result of his ignorance of them. Moreover, due to the lack of self-reflexive moment in his works, Song never makes explicit the role he is assuming. This absence obscures us to see the possible symbolic domination he may impose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to some of the people who has given me help in the writing of this dissertation.

I want to thank my supervisor Dr. Archie C. C. Lee for his assistance and patience. I have changed the title and contents of this dissertation and this increase him a lot of administrative works. His kindness and patience is unforgettable. His criticism greatly improves the quality of this work.

I have been assisted by the material and thought of my fellow students Chan

Chi Wai, Chi Ka Bong, Cheung Hon Keung, Lee Ling Hon and Yip Ching Wah,

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS i

----

CONTENTS ii

1. INTRODUCTION 1

2. BACKGROUND : ASIAN THEOLOGY AS CONTEXTUAL 3

2.1 The Call for Doing Contextual Theol(W 3

2.1.1 Factors leads to the rise ofcontextual theolog 3

2.1.2 Different Models ofContextual Theolou 6

2.2 Constructing Contextual in Asia 9

2.3 Summary 12

3. SONG'S CONCEPTION OF CONSTRUCTING ASIAN THEOLOGY 14

3.1 Doing Theology with Asian Resources

3.2 Song's concept of culture 17

3.2.1 Definition ofCulture 17

3.2.2 Images and Symbols 20

3.3 Song's Doing Theol(W in Asia 22

3.3.1 Raw Material and Context of Theolou 23

3.3.2 'Reclaim Our Own Asianness ' 25

3.3.3 New Orientation in Doing Theolou 26

3.3.4 Doing Asian Theolog by Telling Stories 29

3.4 30

4. CRITICAL ASSESSMENTS OF SONG'S THEOLOGICAL PROJECT 32

4.1 The Interpretation of Culture 35

4.1.1 Prejudices in Reading Culture 36

4. I .2 Reading ofCultural Texts 39

4.2 The Notion of Culture 46

4.2.1 Culture and Human Beings 47

4.2.2 The Scope ofAsian Cultures 56

4.3 Reflexivity and Symbolic Domination 60

4.3.1 Reflexivity of Theory 60

4.3.2 Symbolic Capital and Symbolic Domination 63

4.4 70

5. CONCLUSION 72

BIBLIOGRAPHY 74

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the word 'contextual' became a vocabulary of theology, a drastic change has been taking place in the world of theology. What this word seeks to express is neither simply the adding of local elements to the imported 'theological products' from other places, nor the dressing of the theological immigrants in the local costumes. These two efforts can no longer be considered as adequate. More and more theologians agree that the starting point of theologization should be the experience of local people, rather than ready-made theology, which mainly come from the West. Among these exponents, we can find the Asian ones, and among the Asian ones, we find Choan-seng Song.

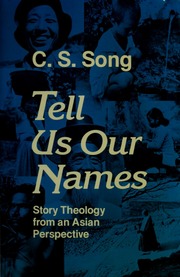

Song, trained in the Western theological tradition and being a professor at the Pacific School of Religion at Berkeley, is one of the founders of the PTCA (Programme for Theology and Cultures in Asia), which is lively and influencial contextual theological movement. His works mainly concentrate on the theoretical justification and exploration of the directions of creative living theology in Asia, and his series of works has a time-span of more than twenty years.

This dissertation is designed to provide a critical assessment of the works of Song, and is divided into three chapters. Chapter 2 functions as a background of the recent discussions in contextual theology. It introduces the factors, both internal and external, that leads to the rise of the concern in constructing contextual theology. Then two classification schemes of different models of contextual theology, which can help us to locate the theological concern of Song; will be presented. We shall also have a discussion on the general concern of Asian theologians.

Chapter 3 iä an effort to reconstruct Song's efforts in constructing contextual theology. Perhaps due his having difficulties with Western systematic theology, or to the fact that Asian theology is still in the course of formation, Song never makes a comprehensive presentation of his theological project. All his works are piece-meal treatment of one or two theological issues. It becomes, therefore, absolutely necessary to reconstruct a relatively clear and panoramic view of his works before a

Unless otherwise stated, hereafter, the term 'theology' refers solely to Christian theology.

critical assessment can be carried out.

Chapter 4 contains a multi-perspective assessment of the theological project of Song. Different theories, borrowing from the fields of hermeneutics, anthropology and sociology, are employed in order to illuminate the different facets of Song's project and to achieve a really critical assessment.

2. BACKGROUND : ASIAN THEOLOGY AS CONTEXTUAL

This chapter is intended to form the background for the understanding of the theological project of Choan-seng Song in the next chapter. We shall, in the first place, outline the idea of contextual theology by looking at the factors leading to the rise of contextual theology, as well as the different models of doing contextual theology. This discussion of the nature and different understandings of contextual theology will be based on the two important works of Robert J. Schreiter and Stephen B. Bevans. Then we shall have a discussion on the theological concerns of Asian theologians in recent years.

2.1 The Call for Doing Contextual Theology

2.1.1 Factors leading to the rise ofcontextual theology

That theology is contextual is now becoming the general consensus among theologians, In the 1950s, the consciousness of context took shape as there was a growing awareness that the "traditional" theologies inherited from the older churches of the North Atlantic community are in discord with circumstances and heritage of other cultures. Christians in cultures other than the North Atlantic ones, together with those marginalized peoples of Europe and North America, began to question the normativeness of the theology bestowed by the missionary. They tried to make sense of the Christian message in their own circumstances by articulating their own theologies.3

It is true that contextualization is a new approach in constructing theology, since classical theology never considers the incorporation of the changing context or culture in the course of constructing theology as necessary. In fact, theology was only understood as 'a reflection in faith with two loci theologici (theological sources) of

Robert J. Schreiter, Constructing Local Theologies (London SCM Press, 1985).

2 Stephen B. Bevans, Models ofContextual Theolov (New York : Orbis, 1992). 3 Schreiter,- Local Theologies, pp. 1-2.

scripture and tradition'. It was construed as a theologia perennis, an unchanging theology. On the contrary, contextual theology adds and emphasizes another locus theologicus : present human experience. Culture, history, contemporary thought forms can no longer be ignored. The claim of objective and ahistorical nature of theology can no longer gain support. In this respect, contextualization is a new approach to theology, which is described as a shift in perspective by Schreiter.

Nevertheless, all theologies are inevitably contextual, since there is no immediate truth. All understanding of the world is constrained, though also enabled by our own situatedness in our context. Every understanding of God is influenced by our own context and history. Thus, even classical theology is inescapably contextual, though they may claim to be universal and ahistorical. In this sense, every theological endeavor is a contextual one, which can be stated in Bevans' words, 'the contextualization of theology ... is really a theological imperative. As we understand theology today, contextualization is part of the vew nature of theolou itself.' [italics mine] Due to the conception of this new theological imperative, and other factors which will be outlined below, though the task of theology remains as the reflection of Christians upon their religious experiences, due emphasis has been paid to the circumstances in which these experiences originate and are nurtured.

Different terms is being employed to expressed this new awakening in doing theology, such as 'contextualization', 'localization', 'indigenization' and 'inculturation' of theology, 'all of these terms point to the need for and responsibility of Christians to make their response to the gospel as concrete and lively as possible. '

But what is the factors that provide the background for the appearance of contextual theology? Bevans suggests that there are both external and internal factors. The external factors point to 'the possibility' of doing theology, while the internal ones sees 'the necessity' of theology to be contextual. He suggests four external factors, which are the results of historical events, intellectual currents, cultural shifts, and political forces .10

(1) Classical approaches to theology are considered irrelevant to and incompatible with the local culture.

(2) The oppressive nature of older approaches to theology. The theological discourses are dominated only by western, white, male theologians.

(3) The growing identity of local churches. With the end of colonialism, Asian and African countries began to realize that the values of their cultures are just as good as, if not better than, those of their colonizers.

(4) There is a new, namely the empirical, understanding of culture provided by contemporary social sciences, which opposes the classicist conception of culture,

The latter sees that there is only one culture, which is both universal and permanent, while the former defines culture as a set of meanings and values, and there are many such sets. Theology is the way religion makes sense within a particular culture.

There are also three internal factors, which are due to the nature of doing theology .11

(1) Incarnation nature of Christianity. Christianity has to continue the incarnation process by becoming contextual. 'God must become Asian or African, black or brown, poor or sophisticated, a member of twentieth-century secular suburban Lima, Peru, or of the Tondo slum dweller in Manila, or able to speak to the ill-gotten affluence of a Brazilian rancher. ' 12

(2) The sacramental nature of reality. Through concrete things, encounters with God in Jesus continue in our world.

(3) A shift in the understanding of the nature of divine revelation. Revelation 'was conceived as the offer of God's very self to men and women by means of concrete actions and symbols in history and individuals' daily lives. '13 Revelation is God's offer of relationship to men and women in the way that they can understand. It is then the task of theology to take seriously the actual contexts in which the revelatory work ofGod is to be continued.

In sum, the changes in political, economic and cultural environments have capacitated and energized the 'contextual turn' in theology. These new currents in turn refashion the understandings of theology itself, which then in turn alter the perspectives on the current environments. Through this dynamic process, that the contextual nature of theology today must be explicitly acknowledged seems to be an undebatable issue now. The questions remain : to what extent and how theology shall be contextual. We are going to look at some endeavors in answering these questions.

Bevans, Models, pp.7-IO.

12 Ibid., p. 8.

13 p.9.

2.1.2 Different Models ofContextual Theolog.'

Both Schreiter and Bevans offer models of contextual theology. Before looking at different models of contextual theology, however, there is a need to clear up some confusion in terminology. Schreiter puts under the umbrella of local theology, three kind of models : translation, adaptation, and contextual models,14 while in Bevans' map of models of contextual theology, there are five models, namely anthropological, transcendental, praxis, synthetic, and translation models. "Contextual theology" in Bevans' sense is more or less equivalent to Schreiter's "local theology". The following table of equivalence may provide further clarification

Schreiter's LOCAL THEOLOGY Bevans' CONTEXTUAL THEOLOGY

Translation Model Translation Model

Adaptation Model

Synthetic Model

Contextual Model Praxis Model

Transcendental Model

Anthropological Model

We will follow Bevans' map of models of contextual theology, which is now reproduced here .16

Transcendental

Model

Culture Gospel Message

Social Change Tradition

Schreiter, Local Theologies, pp.6-16,

This map represents contextual theology as a continuous spectrum, in which different models locate themselves in different equilibrium points in the tension between two important poles • culture and social change, and gospel message and

17

tradition. In this spectrum, the most conservative is the translation model. It presupposes that the essential message of Christianity is supracultural and considers the gospel message as separable from the bound of culture. Although it regards culture as important, if conflict between the gospel message and the cultural values arises, it is the former that is to be preserved with all efforts. 18 The most radical one is the anthropological model, which tries to establish or preserves the cultural identity. Its starting point is human culture, and human experience is the basic criterion of judgment as to whether a particular contextual theology is really a good message to the local people. Human culture is the medium through which God reveals Godself, and it at the same time shapes the way Christianity is expressed. This model 'recognizes that revelation is not essentially a message, but the result of an encounter with God's loving and healing power in the midst of the ordinariness of life. '21 It emphasizes that each culture has its unique way of expressing their own religious experience

Other models are somewhere in between of this two extreme positions. The praxis mode1 concentrates on social change with focuses on the identity of Christians within a culture. What theology concerns is not only reflection on culture but also commitment to Christian action. It sees that culture involves a dynamic change besides constitutes human values and ways of living. Although culture is essentially good but sometimes might be perverted, and requires healing and liberation. The synthetic mode1 tries to keep a 'creative dialectics' among the

above three models. While acknowledging the uniqueness of every culture, it holds that every culture has its bad side and thus can be benefited by other culture, if each culture maintains an openness towards and dialogue with the others. This attitude must be upheld since there is no timeless and straight theology. The last one is the transcendental mode12 which concentrates not on the content of theology but the subject who theologizes. Its concern is not to focus on the essence of the gospel message and tradition, or to analyze the local culture, but the knowing subject's own religious experience. God's revelation is therefore not 'out there' but within human experience. The subject, however, is not one in the cultural vacuum, but, on contrary, nurtured by the very context one lives. Thus the starting point is very contextual and communal, and the subjective experience mirrors the very common structure. It presupposes that though different persons are determined by their own history and culture, their mind operate in identical ways.25

Bevans's and Schreiterrs pictures of different models of contextual theology present to us a very useful mirror by which we can have reflections of our theological reflections and articulations. It helps to locate and formulate the approach employed in this study. Before the elaboration of this approach, however, I would like to have a simple evaluation, based on the framework delineated above, of Asian theologies, especially those proposed by theologians in the PTCA movement. The latter is an energetic and contextual effort in doing living theology in Asia. This evaluation is thus necessary since, although I am in accord with the basic attitudes of doing theology in Asia, I have some reservations of part of the methodologies and presuppositions. Just because what I am trying to do is to theologically reflect on the culture of Hong Kong, which is at least geographically an Asian city, there is a need to justiÜ what I am doing in relation to the spirit of the existing Asian theologies in a broader sense.

24 Ibid., pp.97-110. The term transcental refer to the transcendental method established by Immanuel Kant, which advocates that it the knowing subject who determines the shape of reality. See ibid., pp.97-8.

25 Besides sketching the features ofeach models, Bevans also offers a detail and incisive critique ofeach model.

2.2 Constructing Contextual Theology in Asia

In the light of the delineated by the works bf Bevans and Schreiter, it is not hard to discern the direction Asian theology is heading. The first step of doing theology in Asia is to shatter the fetters imposed by the western Christian tradition. Choan-seng Song criticizes the notion of the identification of the history of the Christian Church with the so-called of 'history of salvation' generated in the history of western theological thought. Westem Christian church, even today, argues Song, cannot resist the charms of monopolization of the history of salvation.

He reproaches western theologians for that

they obstinately persist in reflecting on Asian or African cultures and histories from the vantage-point of that messianic hope which is believed to be lodged in the history of the Christian Church, so that the relations of these cultures and histories to God's redemption become intermediate, and redemption loses its intrinsic meaning for cultures and histories outside the history of Christianity. The universal nature of God's dealing with his creation forfeits its particular and direct application, except within the cultures and histories affected and fostered by Christianity.

Song contends that this kind of mentality actually contradicts the biblical prophetic tradition, which refuses the identification of history of Israel with the totality of

God's presence in history. Though the acts of God in Israel is unique, what the Asian nations need to do is not just to unquestionably accept this fact, but to 'learn how their histories can be interpreted redemptively. ' [italics added] Asian nations, as a consequence, should consider their history as another one in God's salvation parallel to that of{srael.

This realization of the equal status of Asian history in God's salvation, however, is not without a historical background, as we have seen that there are both external and internal factors, suggested by Bevans, that lead to the emergence of contextual theology. Song points out two factors. Firstly, the spiritual vacuum as a result of secularization propels the West to seek helps from Asian faith and ideologies for spiritual revival. This makes both eastern and western theologians pay due attention to faiths and ideologies other than Christianity. The second factor is the failure of western missionary movement in Asian countries. The churches in the West cannot reacts timely and correctly, with their conceptual and propositional theologies, to changing situations and the long-established cultural traditions in Asia.

29

Thus the once held continuous history of salvation is 'interrupted and broken'.

But the road on which Asians construct their own theology is not a straight one.

In a short summary of the directions and contents of Asian contextual theology,

30 Kwok Pui-lan gives us a brief description of the change in doing theology in Asia. She points out that in the past, Asian Christians concentrated on the dialogue with Asian traditional cultures and religions, which produced different indigenous movements. 1 Some of these endeavors have been criticized as irrelevant to lives of ordinary people since the dialogical partners are mainly intellectual elite in society. Other theologies tried to transplant model of Latin American liberation theology, which is in heavy Marxist tone, to Asian context. Kwok argues that this kind of transplantation overlooked the anti-religious sentiment of Marxist framework and

32

was impotent in dealing with multi-religiously characterized Asian culture- Thus, the Asian contextual theology must focus on the political and economical liberations

29 Ibid, pp.220-I. Song advocates that "theology of essence", which is the traditional paradigm, must be replaced by "theology of existence" The question of "what God does" must replace the question Of "what God is", and "we cannot know what God does apart from events and realities in which we are involved existentially." Ibid, p.221.

For example, the Chinese christians in the early decades ofthis century paid much effort in dialogue with Confuscianism, which was, and may still be, considered as the representative, or even the deep underlying structure, of Chinese culture. In recent years, many scholarly works, mainly in historical perspective, has emerged to provide analysis of this important period ofChinese history. These works mostly focus on the Anti-Christian Movement in the twenties. For analysis of the indigenized theology

:

1985)

; for historical analysis of events, see Jessie G. Lutz, Jessie G, Chinese Politics and Christian Missions : The Anti-Christian Movements of 1920-28. (Indiana : Cross Cultural Publications, 1988); for analysis ina perspective ofrelation between politics and religion, see :

1992)

32

of Asian people, and, at the same time, must concern the cultural and religious renewal. ' 33 The emergence of Asian contextual theologies marks the relentless movement under the direction of local consciousness. But will it be running in the opposite direction of ecumenical movement?

Kwok gives a definite negative answer : the mystery of God transcends all our human imagination, and will not be limited by any society or culture. Gospel is universal. It is we, finite human beings, who restrict the understanding of God to particular situation. The universal gospel can only be understood through the contributions from every faith community.34 Douglas J. Elwood has a similar notion. Defining Asian contextual theology as an Asian expression of Christianity, he maintains that Asian theology is not an exclusive or esoteric theology that is designed for Asians only. In his eyes, 'the best Asian theologians are making possible an Asian development of "ecumenical theology', a property of no particular nation or region but the heritage of the whole church. Kosuke Koyama uses the notions of (local) traditions and the Tradition to explain the relationship between local faith tradition and the original Christian Tradition. He contends that Jesus Christ is the source of the Tradition, which cannot be monopolized. Each tradition is only a partial expression of the Tradition.36

No matter what the details of argument are, every Asian theologian would likely hold an inclusive view of the coexistence of the local traditions and the universal tradition, and see the former as constitutive components of the latter, though they may maintain different proportions of emphasis on the two.

33 Ibid, p.4.

34 [bid, p.2.

35 Douglas J. Elwood, "Introduction : Asian Christian Theology in the Making" in Douglas J. Elwood ed. What Asian Christians Are Thinking (Philippines : New Day Publishers, 1976), p.xxviii. Agreeing with Lesslie Newbigin's idea that "there is a core of hard hsitoric fact which remains normative and which forbids us to make the 'context' alone decisive for our thinking and teaching," [original emphasis], Elwood makes a warning that there may be "over-enthusiastic contextualizers who may be tempted to make the 'context' more important than the text'". We will see in the following discussion that theologians in the PTCA movement, at least some of them, do not see this notion as of first priority in their theological reflection. In practice, they, at least implicitly, emphasizes the context more than the text, though theoretically they may claim equality ofboth.

36 Kosuke Koyama, "The Tradition and Indigenisation", Asia Journal of Theoloo, vol.7, NO. l, Apr.,

1993.

2.3 Summary

In the beginning of this chapter, we have pointed out the factors, both external and intemal, suggested by Bevans, that leads to the rise of the consciousness in doing contextual theology. We then looked at different models of contextual theology suggested by Schreiter and Bevans, especially those of the latten These models vary in their different proportions of emphasis putting on the local culture and the Christian tradition. Lastly we have outlined the concerns of Asian theologians in their movement of constructing contextual theology. Different Asian theologians fall in different theological models sketched above.

3. SONG'S CONCEPTION OF CONSTRUCTING ASIAN THEOLOGY

In the previous chapter, we have sketched the concems of constructing contextual theologies. Against this background, we are going to locate the contextual theology of Choan-seng Song, which he and others describes as 'Doing Theology with Asian Resources'. As we may soon note, Song's theological model is actually a representative of the anthropological model, which is the most radical one among the variety of models discussed in the last chapter. This fact may even be sensed from the rubric of his theology. With 'Asian resources', Song and his colleagues, which we will called them 'Asian theologians' hereafter, attempt to put forward a new way of constructing theology, which is aimed to be completely different from that of traditional, western kind.

This radical and provocative claim compel us to raise a set of questions : What is the concem of these Asian theologians? How is it different from that of traditional theology? What are the contents of 'Asian resources'? How do the Asian theologians deal with these resources? Or what are the methods they employ or devise?

These are the questions that we are going to probe in the following pages. It should be mentioned beforehand that there is a focus of concern in our following exploration of the above cluster of questions, namely the notion of culture. It is this notion of culture of Choan-seng Song that we will critically assessed in the sections to come.

3.1 Doing with Asian Resources

If one wants to classiö' Song's theology, one may probably put it into the category of Bevans' anthropological model, which considers the preservation of cultural identity as most important and sees local human experience as the basic criterion of whether a theology is really conveying a good message. I Song traces the history of local theology and reckons World War Il as the watershed, which signifies the rise of local consciousness. He says

See Section 2.1 above for a sketch ofBevans' map of different models ofcontextual theology.

[World War Ill marked the beginning of the end of Westem colonial culture in Africa and Asia. Emerging from the war were newly independent nations preoccupied with the terrifying task of nationbuilding. Inevitably, there was resurgence of the indigenous cultures and religions resurgence that often went hand in hand with a strong sense of nationalism.2

A consequence of this 'resurgence of the indigenous cultures and religions' was a question about the former understanding of the relations between Christianity and cultures. Song is disappointed by results of missionary efforts in Asia. He laments that although enormous amount of both human and material resources was invested, the return in the number of converts was greatly out of proportion and Christians consists only a small minority ofthe great Asian population. How to account for this phenomenon?

Song says that it is due to the missionary approach together with its theological assumption. The missionary approach exercised in Asia in the past was completely ignorant to the well-developed and widely spread cultural, especially religious, reality of Asia. Asian cultures were only considered as pagan, if not evil, waiting for the redemption of Christ as represented by the Western culture. Even the notion of 'anonymous Christian' held by those 'liberal' wing missionary, which states the already presence of Christ in Asian cultures, cannot be accepted. Songs rejects this view as full of 'ignorance and blindness' to the real Asian cultures, which are profoundly constituted by Asian religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism and Confucianism. Just because of these, Song concludes the past missiological history in Asia by saying that

The stereotyped theological and missiological pronouncements on our cultural, religious and historical realities made by our mentors in the West, if not entirely fallacious, are invalid and misleading. ... To some of us Christians and theologians in Asia, ... the theological and

2 Choan-seng Song, 'Culture' in Nicholas Lossky et.al. ed. Dictionary of the Ecumenical Movement (Geneva : WCC Publicatm 1991), 257.

3 Choan-seng Song, 'Christian Theology • An Asian Way' in Yeow Choo Lak and John C. England eds. ATESEA Occasional Papers No. 10 : Doing Theology with GM's Purpose in Asia (Singapore

ATESEA, 1990), 27-8. 4 Ibid., 29.

missiological accommodation made within traditional theology is not only inadequate but counter-productive. It does justice neither to the Christian faith nor to other religions and cultures. For us the reality of

Asian religions, cultures and histories developed outside the orbit of Christian influence presents a theological challenge of a radical kind. It touches our theological being to the quick, forces to stop singing the theological tunes we have leamt from some where else, and inspires us to compose our own theological symphony.

Song calls this understanding a 'hermeneutic of suspicion'. This hermeneutic requests a screening of all the ready-made theologies and missiologies produced by those Western theologians who are '"genetically" incapable of knowing what it means to Live in the world ofBuddhist culture, Hindu culture, or Confucian culture. '6

Song believes that Asian Christians can no longer rely on the theological products of Western worlds, but must take up their responsibility to theologize their own Asian experiences by using Asian resources. The way of 'doing theology with Asian resources' can be regarded as the central direction of a group of Asian theologians, among which Song acts as one of the main spokespersons. These theologians put forward a theological movement, the Programme for Theology and Cultures in Asia (PTCA). As the name may suggest, PTCA is specifically interested in tracking the culture of Asia. Culture, including religion, thus provides the substance for Asian theology.

In Song's eyes, only through the study of cultures (Asian local cultures of course!) can theology be true theology. Otherwise, theologization will only be reduced to an intellectual game, as can be illustrated by Western, traditional theology.

Song actually proposes a new way of theologization, which he together with other Asian theologians regard as not only distinct from traditional theology at the substantive level»but also at the methodological level. Before making a tour on Song's theological method, a few questions have to be cleared up first : What then is culture? How is Asian cultures distinct from others? Or, in other words, what are the characteristics of Asian cultures? How to interpret Asian cultures anyway?

5 Ibid, 27-9. 6 Ibid, 27.

7 Choan-seng Song, 'Freedom of Christian Theology for Asian Cultures : Celebrating the Inauguration of the Programme for Theology and Cultures in Asia' in Asia Journal of Theology, vol.3, No. 1, Apr. 1989, 88-9.

3.2 Song's concept of culture

3.2.1 Definition ofCulture

It may seem contradictory and ridiculous at the first sight to provide a study of Song's theology at the conceptual level, as he often seems to reject putting culture on the desk of conceptual analysis. In fact, he reminds that in Asian cultures, 'we are not dealing with abstract concepts of Asian cultures, but living entities; not general idea but "dynamicforces that create or destroy the lives ofpeople."' [italics added]8 However, theology that excludes conceptual analysis as its subject does not (cannot?) defr conceptual analysis of itself. This conceptual analysis is deemed necessary since Asian theologies often impress us as interesting but loose. Without such kind of systematic treatment, critical assessments, the task of this dissertation, cannot be carried out. More importantly, it is only through a thorough and systematic reconstruction can Asian theologies be not only critical towards others, but also be self-critical. Application of the 'hermeneutic of suspicion' to oneself appears to be the most neglected work of Asian theologies themselves. We will have more on this problem in the next chapter.

In Song's view, only by carrying out a re-conceptualization of Asian cultures, can Asian theologians on a new way of theologization in their ox,vn places. Song firstly gives a head-on attack on Ctraditional theology'. He argues that what the

8 Ibid, 89.

9 Third world theologians even coin their theologies as 'unsystematic'. See :

' 83 ' 1985 {F 9 1. This anti-systematic bias may be related to the anti-Western-traditional sentiment in theologization of Asian theologians. 10 We may well ask : what is 'traditional theology' anyway? The impression that can be got in Song's theology seems to be too vague. Sometimes he mentioned one or two early church fathers, e.g. Tertullian, or a few modem theologians, such as T.F.Torrance, Karl Barth, Paul Tillich, Dietrich Bonhoeffer Is the whole western theological tradition a unifring stream? Are all the 'traditional' theologians unconcern with the lives of people? How about Barth's Barmen Confession which attacked the Nazi's making of idols for people? How about Bonhoeffer's project of assassination of Hilter and his return to his home country from America just to be with his own fellow Christians? What about the philosopher-theologian Simone Wile's working together with workers to the very end of her life? And can we neglect that the Rheinhold Niebuhr's theology of nature of man is a direct consequence from his being a pastor in Detroist for more than ten years? Can we draw the conclusion that the social gospels of YMCA/YWCA, which was being applied to China in the early decades of this century, are doing something unrelated to the lives of ordinary people? We can still add more if we want. What I want to point out is Song's over-simplification ofthe whole westem theological tradition. He often put westem theologies in cultural vacuum, which is the very act that he himself reject!

theologians in the West concerns is only the abstract concepts of culture and gospel. For them, culture is incompatible with the Christian faith; and Song terms this attitude the 'theological bias against culture'. Il And it is this attitude that Asian theologians must correct.

Although Song seldom provides us with definition of cultures in his works on cultures, occasions can still be located. 1--1e sees culture as an all embracing constituting force. He says •

We are all under the power of culture into which we are born. Our cultural heritage makes us what we are. Our views on life and the world are formed under the direct and indirect influence of our cultural traditions.12

We may conceive, from this definition, that culture is a molding force that shape both our life-views and world-views. Human seems passive in this respect. Song nonetheless also provides us with another formulation of the human-culture relationship by saying that

In culture we have to do with human beings - us human beings. Culture is us - what we are, what we stand for, how we live and how we create meanings that transcend the present. Study of culture, then, is study of human beings.

This formulation puts the emphasis on the human side rather than the culture. Human is no longer a passive product of culture but rather an active creator of meaning. Culture only acts as environment for us to live in and create. In fact, Song always directs our attention to the human beings, the central focus of his conception of doing Asian theology. For him, it is completely making no sense to say such thing as 'culture in Asia' without at the same time talking about the men and women of

Asia. Every time we mentions about Asian cultures, we must be speaking of Asian

Song, 'Freedom', 88-

Choan-seng Song, Third-Eye Theolov (New York : Orbis, 1979), 6. This definition of culture situates itselfvery near to those provided by anthropologists, as we shall see in the next chapter. In fact, Song suggests that theologians should learn from cultural anthropologists, sociologists and historians of religions in the study of culture. See 'Freedom', 88.

people. These people are living beings, not ideas; they have their concrete lives. 'When we seek to understand the meaning of cultures in Asia, we are in fact seeking to understand the meaning of the life that people in Asia live with all its precariousness and hope, in fear and in expectation. To explore theologically Asian cultures is to explore the history of Asian people, to listen to their stories, to hear the cries of their hearts' 14

As this notion suggests the equivalence between culture and people, culture cannot be stagnant, since people are not stagnant. Culture is actually historically formed. It has its starting and ending points, as well as a life in between- 'Even a culture already dead - culture, for instance, housed in a museum - was once alive and active in a particular society and in a particular time. Culture is a spatial-temporal reality.' 1 This living history is not only a self-developmental process of an isolated culture, but also one consists of assimilation and rejections of foreign cultural elements. No culture can ever claim of monolithic which is a uniform cultural entity. We should note that what really interested Song here is not the cultural change itself, but rather the rejection of cultural imperialism of the West. He suggests that even Alexander, who has such a great military prowess, failed to subsume the cultures of the Arabs, the Indians and the Nile Africans. And even Western culture itself is not monolithic but rather a term signifring a bundle of cultural patterns, It is the cultural diversity and plurality that he wants to uphold, for he believes that 'the vision of a world community must be a vision that presupposes fruitful and constructive interactions among rich and diverse cultural heritages and characteristics. ' Thus he proposes the replacement of Asian singular 'culture' by the plural 'cultures' in our discussion.17

Culture is the lives of people, but how are cultures manifested? One of the ways is through symbols and images.

Ibid.

15 Ibid, 88.

3.2.2 Images and Symbols

It is not easy to grasp what Song means by images and symbols, since he never prepares for us any clear definitions of them. He nonetheless has treated them as a separate topic and points out some characteristics of them.

Song does not tell us what images are, although he advocates the significance of imagination. He says 'imagination is the power of human self-transcendence. It gives us freedom from the limitation of time and space. ' By the power of imagination, we are no longer bounded by time, we can 'transpose ourselves from the present to the past and to the future. ' We are no longer bounded by space either.

The power of imagination transports us from our own space to the space of others. With imagination, communion with others will be possible, even though we and others are separated by space or even time. Moreover, the power of imagination applies not only between human, but also between human and God. Prayers are made possible through imaginations. Song maintains that 'imagination is the energy of human life. '

What is a symbol then? Song tells us what a symbol is through its relation with an image. The function of symbol is 'translating visual perception of images into meanings. A symbol is the meaning of an image. ... Symbols, at any rate, are images reconstructed to direct people to the meanings of images.... Symbolism is in fact semantics of images.' 20 Song does not make clear to us whether symbols are images or meanings of images. Neither does he tell us clearly how and why images are reconstructed. He, however, does tell us something about the nature of symbolism. He uses the example of sacred stone as an illustration.

He points out that when a stone becomes a sacred one, nothing of its appearance has changed- For those who are outside the culture where the stone is considered sacred, the stone is in no difference from any ordinary one. But for those

G insiders', the stone is by no means an normal one, 'it is now a stone bearing a meaning representing an awesome presence of a reality beyond itself.' This process of changing a stone from 'secular' to 'sacred' is actually a symbolization process. In this process, a stone change 'from a stone to an image of a sacred reality to symbolism of the presence of that reality.' Symbolism is the 'grappling with the meaning of the sacred in the secular. '21

We may now see that, for Song, both imagination and symbolism is the path through which human can transcend their limitations to reach for the sacred reality. 'The world of images and symbols is a real world. It is a world in which human beings discover the deep meaning of life and experience the power of transcendence. '22 But how does these images and symbols come? Those artists 'endowed with uncanny power.' Song describes poets and artists as 'priests of images and symbols', who are responsible for the making and remaking of the latter, and

They reveals to us the mystery of God's creation that defies the penetration of our everyday language. They show us what the real world must be like with the images that contradict our common logic. And they disclose to us the subtlety and complexity of human relations using symbols that shock and disarm us at one and the same time.

Through their efforts, symbols are possible. This conception has a clear assumption : symbols is created by artists. But a series of questions instantly pop up in our mind Is symbol an object itself or a meaning carried by an object? Does the meaning of the symbol appear in the process of interpretation or in itself? Is symbol private or public?

Is symbols just a creation of an artist? Does that creation constitute what a symbol is? In other words, is symbolism a personal work or an group phenomenon? We shall deal with these questions in the next chapter.

Creators of images and symbols may not be at the same time the custodians of them. There are priests of images and symbols, who are the interpreters and perpetuators of the latter. Because what images and symbols concern is the sacred power, the priests are endowed with power also. And Song believes that the fact is

Ibid

22 Ibid, 5.

23 Ibid, 3.

that just because of this sacramental power, there exists power struggle in a religious hierarchy. He sees such struggle as an irony for that power struggle is most profane treatrnent of the sacramental power. And the history of religions, including

Christianity, is full of such ironies.

Song never forgets to point out the evil side of traditional Christianity. He argues that the interpretations of images and symbols are often developed into teachings, doctrines and dogrnas within religious institution and community. It is these very acts that images are stylized and symbols are formalized. As a result, the power of symbols of pointing to something other than themselves is restrained, and it is the root-cause of religious absolutism and theological dognatism. Out of these absolutism and dogrnatism, the dichotomization of orthodoxy and heresy cannot be avoided. All the symbols and images of Asian cultures are considered as idols. Converting to Christianity requires the smashing of these symbols and images to pieces. Song maintains the 'cultural particularity' of all symbols and images, and contends that if the cultural limitations of Christian symbols and images are overlooked, no fruitful interaction between the Christian-Western images and symbols and the local-indigenous ones.

He laments that our imagination is too often suffocated by too much tradition. Imagination must be preserved with all our efforts if we do not want to be 'dictated by animal instincts for survival and by preoccupation with biological needs.' Without room for symbolism, religion would only be reduced to literalism without life.

3.3 Song's Doing Theology in Asia

The above understanding of Song's conception of culture sets up the stage for his theologization. We now move to Song's doing theology with Asian resources. The following pages will cover four areas : (1) raw material and context of Asian theology; (2) reclaim the Asianness of Asian theology; (3) new orientation in doing theology; and (4) doing theology by telling stories.

3.3. I Raw Material and Context of Theolog.'

From the above discussion, we can infer that, for Song, the subject matter of theology which is justified is not abstract ideas, but something related to the concrete lives of people which is manifested in culture. It is the message that appears again and again in Song's work.

He forcefully reject the concern of 'traditional theology' . 'For theology to refrain from asking questions at this point is to flee back into the shelter of academic theology, which is more interested in the metaphysics of God than in the concrete acts of God in society and history. '28 In his view, theology would become a vain effort if it regards God as a problem of idea, which has nothing to do with the real life of people. Unless we abandon this pure academic kind of approach to understand God and move into the real life situations, in which God acts, theology will have no relation to Asian people.

There we see the theological presupposition of Song : 'God is already in human history and on earth.' [original emphasis]29 The implication of this presupposition is not the change in the understanding of the nature of God, which is still confined to Intellectual area, but the very starting point of doing theology. The starting point is not the abstract, immovable God, but the history of human beings.

Both attitudes to God and human have to be reoriented. Firstly, the understanding of God has to be reoriented. God is a God involves in human history. He gives response to the experience of human beings. To study the lives and histories of humanity is to study God's creation. 30 Theology is then an effort to make sense of God's involvement in human history, but not intellectual reflections on the doctrines or teachings of the church alone. 'It is a feeling of God's heartbeats in the heartbeats of Suffering human beings. It is the touching of God's compassionate heart in the tormented hearts of our neighbours. '31

theologization in Asia, one may refer to his 'Ten Positions' in doing Asian Theology, in Tell Us Our Names (New York : Orbis, 1984), ch. I28 song, Third-Eye, 80. 29 Ibid, 85.

Ibid, 95.

31 Choan-seng Song, 'I Touched the Theological Heart in Japan' in East Asia Journal of Theolou, vol.4, no.l, 1986, 10.

Secondly, at a consequence, the position of human in theological inquiry has to be re-situated. The questions to be asked in theology are 'human questions', the questions conceming the ultimate meaning of life as we encounter the daily life in human history. Theology must concerns people in their everyday lives together with their suffering and joy. Theologians must listen their weeping and laughter, they 'must be able to touch the hearts of women, men and children who seek liberation in body and in spirit from centuries of oppression, poverty, fear and despair, who struggle to regain their rights to be human. ' It is these Asian people who are in struggle that Asian theologians must identify with. They are the sources of the0105'. Study of humanity must precede the study of God. Song considers this kind of theology completely distinct from traditional one, and terms former 'living theology' , since

God who invites us .. to do theology is a living God. The community in which God calls us to do theology is a community of living human beings. And those of us who consciously respond to that invitation and that call to do theology are living Christian persons. Theology - a joint enterprise of the living God, living human beings and theologically conscious living Christians - has to be living, then. [original emphasis]

35

Living human beings have their living problems. These problems--social, political, psychological, ecological, etc.—are the subject matters of theology, they are the context of theology. For Song, context is neither the static space-time, nor sociopolitical and cultural-religious framework that shapes theological effort, but rather 'a particular space-time where the living God interacts with living human beings in suffering, in judging, in healing and saving.

3.3.2 'Reclaim Our Own Asianness '

The people who Asian theologies should concern are those who are living in Asian cultures. As implied by the notion of culture conceived by Song outlined above, cultures are not abstract concept waiting for analysis, but are real forces that shape and condition the lives of people. To speak of Asian cultures is to speak of Asian people. To peruse Asian cultures theologically is to peruse the history of Asian people. Thus the correct questions about cultures should be something like : 'How do human beings ... fare in Asian cultures? What has a culture in Asia done and what does it continue to do to its people? Is it oppressive or liberating? Does it help create a space of freedom in the life of people or does it deprive them of that space? Is it a culture that allows to justice for the powerless and the marginalized?'38

In Asia, the socio-political and cultural-religious realities can, Song believes, be represented by 'the overwhelming presence of the poor in the midst of "economic development and prosperity'.' 9 Asia is very different from all the rest of the world in terms of the degree of suffering. The number of people in suffering exceeds even the sum of those of the rest of the world40 Asia is full of women, men and children whose spirits have been in oppression, poverty, fear and despair, and Asian people are in constant struggle to get themselves liberated. Thus, we may reasonably point out that it is not all the living human beings, but only those who are politically oppressed and economically kept poor, who are of interest to Song. Or we may say, only they are the living people cared by the living God. For this reason, some of the people can no longer be accepted as Asian people, even though they are geographically situated in Asia. Asia must be characterized by suffering and oppression. 'This is the Asia betrayed by the prosperous Hong Kong, the orderly Singapore, the industrialized Japan, and by pseudo-democracy in most Asian

countries. '41

Thus, Song contends that it is burden of Asian theologians to abandon the old way of constructing theology and switch for a completely new one. He urges 'to reclaim our own Asianness for our theological tasks, and to be able to carry on our

37 Song, 'Freedom', 89.

Song, 'Freedom', 90.

39 Song, 'An Asian Way', 29.

40 Choan-seng Song, Jesus, The Crucified People (New York : Crossroad, 1990), 8. 41 Ibid.

theological responsibility with our fellow Asians.' [emphasis added]42 Song rejects all those efforts ofjust adding an 'Asian colour' to Christian theology, or 'sprinkling traditional theology with oriental perfume'. Asian theologians must search for their very Asian roots, retum to their Asian womb, and compose their own 'theological symphony' .43 All these call for a new orientation in doing theology.

3.3.3 New Orientation in Doing The0100'

The theology that can 'reclaim the Asianness' must be relevant to the Asian cultures. But how? Through 'transposition', Song argues. The theology which is developed in the West must be transposed into other cultures, lest no relevancy is possible. But what is transposition then? Song gives us three steps of transposition.

The first transposition involves a shift in from one particular place or time to another. It refers to the process in which the Christian faith is transferred from the Western worlds to the so-called Third World. An obvious example would be the missionary expansion carried out during the last two centuries. The second transposition relates to the communication between the above two worlds. It concerns how the Christian message can be transmitted and received. It can be called the translation process, provided that it refers more than just the formal or linguistic problem; it has to do with the substance of the message which the church has to communicate. The third and the last one attends to what Song regards as the most important one, namely the process of incarnation. In explicating the meaning of incarnation concerned here, he says that

no cultural assimilation could take place without the two cultures becoming "incamate" in each other. It is neither simply a matter of imitation nor a matter of uncritical fusion. It is a matte of an alien culture "become flesh" in a native culture. A metamorphosis must take

42 Song, 'Freedom', 87.

43 Song, 'An Asian Way', 30.

44 Song, Compassionate God, 5-7.

45 Ibid, 8-10.

Song sees 'incarnation' as the heart of all theological efforts in dealing with the question of relations between Christianity and cultures, such as indigenization, contextualization, acculutraion etc. See 'Culture', 258-9.

place in the cultures concerned.

In other words, the transposition of a foreign culture to a native culture cannot be regarded as successful unless the two cultures are merged together to the extent that the former has become already part of the native culture. Song illustrates the idea of incarnation of the gospel by the example of the May Fourth Movement in the second decade of this century. In this movement, some held that the traditional Chinese culture should entirely abandoned without any sympathy, while the Western ideas accepted without questions, in order to save China. Others maintained that Chinese culture can be kept intact during the introduction of foreign ideas. Song sees that neither side was correct since 'it is neither a matter of imitation nor a matter of uncritical fusion. It is a matter of an alien culture "become flesh" in a native culture. ' Both the Chinese cultures and the imported foreign has to be transformed.

Here we meet the problem of the understanding, which can be technically called hermeneutics. Song once asked the following set of questions

How to interpret the message of the Bible? How to understand the Christian faith? These were our central questions. But interpretation in relation to what? Understanding in what context?

For him, the biblical world of faith and the Asian world of faith are two with little in common. But if we can dig through the surfaces of them, we can find their common cores, namely 'the human spirit in agony and hope in the grasp of the divine spirit of love and compassion.' The two worlds come into 'intense interaction' at 'the very heart of struggle for human life and destiny.' Song asserts that this 'intense interaction is none other than "interpretation" or hermeneutic. ' In fact, theology is itself a hermeneutics of the actions of both God and man in the human community. The gospel message must be understood through this hermeneutical activity. Thus there is no 'change-proof' message, not even the gospel. In order to have the gospel known, it must be interpreted, it must be fused, or incarnated into the native culture. But how can this incarnation take place in the doing of theology? Song suggests a reorientation of theological exploration with four elements : vision, community, passion and 'imag-ination'

The vision in doing Asian theology relates to the new understanding of God and human lives and history discussed above. The content of this vision is that 'God has been personally involved in the Asia since the beginning of creation.' Such vision is also a vision of hope. It is a vision of 'Jesus suffering with the people, empowering and reconciling them in their struggle for meaning, justice and love. It is a vision that enables us to encounter Jesus in the redemptive power at work in society and among people. ' This vision of hope is important, Song contends, since despair is more common and more real than hope in most Asian countries.

Community is another element in theology of Asia that must be emphasized. Theology without community is like fish without water, Song added. He advocates that 'God is the God of community' who participates in his own creation as a member of the community. By Jesus (incarnation), God 'dwell among' the Asian community 'peopled with sun, moon, stars, trees, fishes, animals and human beings.' This community is the Christian church, that is the community of believers, which bear witness in word and in deed to the good news of God's saving love in Jesus. But doing theology needs another community : the community of the people with different cultural and religious commitments of the whole of Asia. It is this community that provides the necessary resources for theology.

The third element is passion. Doing theology in Asia is to resonate with the loving and suffering of the people, to respond to that passion at the heart of Asian humanity. In giving this passion, theology at the same time has to give account of God's passion, his loving and suffering, towards his creation. This passion is the passion of hope and new life.

The last element concerns 'imagi-nation', which has been mentioned in previous section. Without the power of 'imagi-nation', theologians cannot look through the surface of live to the very struggling hearts of sufferings. 'Imagi-nation' enables theologians to image of the real life of men, women and children as well as to image God and his thoughts.56

After all, by what means all the above be put into practice? How can 'doing theology with Asian resources' be achieved?

3.3.4 Doing Asian Theology by Telling Stories

By telling stories, Song asserts. In discussing the merits of doing Asian theology by telling stories, he once quoted the saying of one of his colleagues :

There I realized the potential power of popular culture-literary products as tools for crystallizing and articulating the most profound ideals, aspirations and longings of the common Asian who is often powerless, voiceless, exploited and oppressed. I saw that even the most seemingly harmless folklore stories can in fact be the vehicles of a popular protest movement and, therefore, function as an object of theological exploration on the very theme of liberation in the Asian setting.57

The ideas in this quotation is a representative of the view of doing theology by telling stories. I want to mention some main points here. Firstly, as Song explicitly stated, this story-telling approach is one starts from the bottom up which begins from the human community, but not one from the top down which kicks off from the world of ideas and concepts. Therefore, secondly, this approach put the common folks at the centre of the their concern. Through stories, the lives of the common folks shall be understood, and theologians can come close, feel what the common folks feel, hear their laughter and sighs.58 Thirdly, the folklore stories not only record the feeling, but 'can in fact be the vehicles of a popular protest movement.' In other words, by analyzing the contents of the stories, we may obtain what is just needed,

% Ibid Song suggest that Vintage' should be used as a verb : 'God gave the power of imaging to humankind so that the latter can image God in human persons - God not as an image, not as an ikon, but God as passion, loving and suffering, in people. ibid.

37 Song, 'Freedom', 86. 58 Ibid, 86-7.

the direction, of political movement. This direction is the liberation of people. Song advances that 'in stories of ours we heard the echoes of the humanity seeking liberation contained in the stories of the Bible.'59 In both the Asian stories and the biblical stories, we can find both hopes and power for liberation. This point implies the last one, which refers to the purpose of God. The work of an theologian is not only to listen to these stories, but must listen theo-logically. That is, by listening to the Asian stories, we know the purpose of God in Asia, and we get the hope in God

60 revealed through the incarnation of Jesus Christ.

Listening with hearts is thus the very task of theologians. Song renounces the role of objective observers or disinterested spectators who concern nothing of the human problems. What theologians have to achieve is a 'communion of souls and spirits seeking an "ultimate" answer to "penultimate" questions of the present life. '61

3.4 Summary

In this chapter, we have gone through the conception of theology of Choanseng Song. We have laid out the reasons suggested by him for the reconceptualization of theologization in Asia. He maintains that the traditional way of

theologization is and was unsuitable for Asia, since it completely misunderstsood not only Asian cultures, but the very concept of culture they upheld is mistaken, since it wrongly opposed the gospel to the Asian cultures. We have delineated Song's notion of culture as well as his understanding of images and symbols, which are the very manifestation of Asian cultures. Song's conception of Asian theology is a direct implication of his conception of cultures, We have draw the picture of the content and method of his 'doing theology with Asian resources', including the raw material for and context of doing theology, the meaning of the 'Asianness' of Asian

59 Song, 'An Asian Way', 32.

60 Ibid Song has actually given us an example of doing theology telling Asian folklore stories in his work The Tears of Lady Meng ( Geneva : WCC, 1981). Through the story of Lady Meng, Song celebrates the 'paradoxical power ethics' 'a power ethic not built on powerfulness but on powerlessness' which believes that 'powerlessness can transform into powerfulness through the power of tears, that is, the power of love and turth.' (59) What this story reveals the history Ofthe cross and resurrection in Asia Song contends, is in accord wsith the biblical revelation. (65-6) Thus through this example of Song, we can better know what doing theology by telling stories means. 61 Song, 'An Asian Way', 34.

theologies, new orientation in doing theology, and the method of doing theology by telling stories.

4. CRITICAL ASSESSMENTS ON SONG'S THEOLOGICAL PROJECT

In order to assess the project of doing Asian theology proposed by Choan-seng Song, it is our first task to find out some suitable measuring rods. The measuring rods employed here are mostly fabricated by social scientists and philosophers. 1 And we find that these tools are really powerful ones, especially in terms of their critical abilities.

The first thing to be assessed is the interpretation of culture. Assessment shall be given with respect to both the presuppositions and the methodology of interpretation. The problematic of the first one is how interpretation is at the same time enabled and constrained by the situatedness of the interpreter, while that of the second is how an interpretation can be a rigorous performance instead of a loose free-association. For these purposes, contemporary hermeneutical theories would be invoked in order to clarify, in our view, some confusions appear in the works of

Song

The second set of measuring rods is chosen for assessing the notion of culture appearing in the works of Song. Culture, however, is a complicated and elusive concept that seems to de%r any definition. It embraces a wide range of meanings, materials, processes, differences, conflicts. Most importantly, different people carrying different spectacles get different images and understandings of it, and a variety of designations of the word 'culture' thus result. Nonetheless, efforts from different academic fields have been paid to capture the nature of culture. Among all the endeavors in understanding the culture of ordinary people of any local society, anthropology2 seems to be hitherto the most powerful academic discipline. Actually, it is the aim of anthropology to study culture. This fact can be illustrated by looking at the task of anthropology, namely the study of culture in terms of all aspects of

I In fact, Song himself has more than once suggested that theologians must take seriously into account the studies and findings made by social scientists. See C. S. Song, 'Freedom of Christian Theology for Asian Cultures : Celebrating the Inauguration of the Programme for Theology and Cultures in Asia' in Asia Journal of Theoloo, vol.3, no. I, Apr., 1989, 88; 'Christian Theology • An Asian Way' in Yeow Choo Lak and John C. England eds. ATF-SEA Occasional Papers No. 10 : Doing Theology With God 's Purpose in Asia (Singapore : ATESEA, 1990), 37.

2 Anthropology here refers specifically to cultural anthropology, which is one and the most influential sub-discipline of anthropological science. This designation applies hereafter, unless otherwise stated.

living of different people, as outlined in some standard textbooks of cultural anthropology:

Anthropology is devoted to the study of humans as cultural beings . anthropologists concern themselves with variety of ways people live, with the development of those ways over time, and also with the development of human body and the ways people's bodies influenced their lives. ... anthropologists look at different human groups from the perspective of the different cultures these groups share. A main objective of anthropology is to go beyond simply understanding the groups themselves and beyond just increasing understanding of our own societies, to an increased understanding of all humanity through achieving a better grasp of how culture works in the lives of all humans regardless of where or when they live. The task of anthropology is to examine the whole array of human societies and lives in order to contribute to the fullest possible understanding of humanity as a whole. [italics added]

'Cultural anthropology' is often used to label a narrower field [relative to the whole anthropological discipline] concerned with the study of human customs, that is, the comparative study ofcultures and societies. [italics added]

All types of cultural anthropologists may be interested in many aspects of customary behavior and thought, from economic behavior to political behavior to styles ofart, music, and religion ... The distinctive feature of cultural anthropology is its interest in how all these aspects of human existence vary from society to society, in all historical

periods and in allparts ofthe world. [italics added]

Ln sum, we can say that (cultural) anthropology is the discipline which set culture as its subject of study. It covers every component of cultures from different angles, which means every aspect of human existence. Besides culture as such, it also studies culture in relation with social structure, social action and personality. It examines how culture is constituting and constituted; or in other words, how individual members of society are shaped by culture and how the former in turn constitutes and changes the latter. The objects anthropology studied, spatially speaking, include virtually every society, and temporally speaking, extend from prehistorical buried tribes and cities to modern complicated ones. Thus the knowledge from anthropological studies shall greatly enhance our understanding of culture. And we shall show that this enhancement is a very needed improvement of the project of Song.

Besides this wider notion of culture, we will also deal with a narrow issue : the scope of Asian cultures. Song often reminds us of the pluralistic nature of Asian cultures. With the help of a substantive study of the culture of Hong Kong by a sociologist, we are going to show that the pluralist appearance of Song is actually a fake one.

The last set of measuring rods are borrowed from an important French social theorist, Pierre Bourdieu, for the self-critique of theologians themselves. Bourdieu proposes a reflexive sociology, which, on the one hand, puts the results of study based on theory back to modify the theory itself, and, on the other, using the theory to study the field in which theory arises, namely the academic field- Bourdieu's theory helps us to see the role of theologian, as well as what is going on in the process of theologization, from a sociological point of view.

With the aid of the above frameworks, the assessment on Song's project of theology of Asian cultures will be divided in three parts, which respectively deals with three problems concerning : (1) the interpretation of culture, (2) the notion of culture, and (3) the reflexivity and symbolic domination.

The Interpretation of Culture

The first step in all sorts of contextual theology will undoubtedly be the study of the local cultures. What this study involves is actually the interpretation of cultures. This work is no simple and direct work as it appears and the topic of interpretation has perplexed western philosophers from the very beginning of Greek philosophy, In the past two centuries, however, philosophers have make a lot of breakthroughs in the understanding of the nature of interpretation, as well as the method of interpretation.

In the course of dealing with the project of doing theology proposed by Song, we actually meet, both explicitly and implicitly, the questions of interpretation.

Explicit are those concerning the reading of folklore stories and biblical exegesis. Implicit are the very presuppositions of reading cultures, such as the role of the interpreter, the enabling and constraining factors in interpretation. Until these questions are answered, I believe, no rigorous interpretations in depth can be obtained.

4.1.1 Prejudices in Reading Culture

One of the main efforts of Song's theological proposal is making explicit the weaknesses of traditional theology. In his discussion of images and symbols, he complains that too much tradition has already suffocated our imagination. He believes that unless we throw off the yoke of the Western tradition of theology, it is impossible for us to construct our very own Asian theology. So he asks Asian Christians to do their theology with their own resources. And why not? Is it not freeing ourselves from the bondage of tradition, at least the western one, that we are able to have our very Asianness back, and only by doing so, that we can construct our own theologies? By the help of philosophical hermeneutics, I want to show that this idea is actually a pseudo one, though it seems sound at the first sight.

In his works on philosophical hermeneutics, Hans-Georg Gadamer explores the very nature of understanding. One of the questions that he what to solve is : how is understanding possible? By tradition. To start with, we will look at Gadamer's defense of 'prejudice'. Based on the insight of Heidegger, Gadamer gives the following formulation on prej udice

It is not so much our judgrnents as it is our prejudices that constitute our being. This is a provocative formulation, for I am using it to restore to its rightful place a positive concept of prejudice that was driven out of our linguistic usage by the French and the English Enlightenment. It can be shown that the concept of prejudice did not originally have the meaning we have attached to it. Prejudices are not necessarily unjustified and erroneous, so that they inevitably distort the truth. In fact, the historicity of our existence entails that prejudices, in the literal sense of the word, constitute the initial directedness of our whole ability to experience. Prejudices are biases of our openness to the world. They are simply conditions whereby we experience something whereby what we encqunter says something to us. This formulation certainly does not mean that we are enclosed within a wall of prejudices and only let through the narrow portals those things that ca produce a pass saying, 'Nothing new will be said here.' Instead we welcome just that guest who promises something new to our curiosity.

In this formulation, Gadamer tells us that prejudice is not necessarily a hindrance to have clear knowledge. Behind this negative view on prejudice is the believe of the possibility of clear and objective truth through self-reflection. Gadamer rejects this argument. He contends, it is that very prejudice that is enabling in our understanding of the world around us. This prejudice is 'our whole ability to experience.' We are unable to get rid of it, since it arises out of our very human finitude. We can only look through our own pairs of spectacles, or we do not see at all.

But are not there blind prejudices in any understanding? Yes, but we cannot get around these blindness through clearing up of our prejudices since it is impossible. Accepting our dependence on prejudices, however, does not implies that there is no way out of our blindspots, we are not 'enclosed within a wall of prejudices'. For Gadamer, it is in and through the encounter with works of art, texts, and more generally what is handed down to us through tradition that we discover which of our prejudices are blind and which are enabling. For 'it is only through the dialogical encounter with what is at once alien to us, makes a claim upon us, and has an affinity with what we are that we can open ourselves to risking and testing our prejudices.' Here we encounter Gadamer's famous idea 'fusion of horizons.' 'The horizon is the range of vision that includes everything that can be seen from a particular vantage point. Applying this to the thinking mind, we speak of narrowness of horizon, of the*possible expansion of horizon, of the opening up of new horizons, and so forth. '8 In Gadamer's eyes, there can never be a truly closed horizon. It is through our encounter with others with their horizons that our own horizon is

6 Hans-Georg Gadamer, Philosophical Hermeneutics, tr. and ed. David E. Linge (Berkeley ; University of California Press, 1976), 9.

7 Richard J. Bernstein, Beyond Objectivism and Relativism (Oxford : Basil Blackwell, 1983), 128-9. 8 Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth andMethod tr. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall (New York Continuum, 1994), 2nd ed., 302.