As of August 2017, the book had peaked at The New York Times No. 4 bestseller in hardcover nonfiction.[1]

Contents

1Content

2Reception

3See also

4References

5External links

Content[edit]

- In Why Buddhism is True, Wright advocates a secular, Westernized form of Buddhism focusing on the practice of mindfulness meditation and stripped of supernatural beliefs such as reincarnation.[2]

- He further argues that more widespread practice of meditation could lead to a more reflective and empathetic population and reduce political tribalism.[2]

- In line with his background, Wright draws heavily on evolutionary biology and evolutionary psychology to defend Buddhism's diagnosis of the causes of human suffering.[3]

- He argues the modern psychological idea of the modularity of mind resonates with the Buddhist teaching of no-self (anatman).[3]

Reception[edit]

Why Buddhism is True received a number of positive reviews from major publications.

A review in The New Yorker by Adam Gopnik stated, "Wright’s book has no poetry or paradox anywhere in it. [...] Yet, if you never feel that Wright is telling you something profound or beautiful, you also never feel that he is telling you something untrue. Direct and unambiguous, tracing his own history in meditation practice—which eventually led him to a series of weeklong retreats and to the intense study of Buddhist doctrine—he makes Buddhist ideas and their history clear."[4]

The neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, reviewing the book in The New York Times, wrote, "Wright's book is provocative, informative and, in many respects, deeply rewarding."[5]

Kirkus Reviews called the book a "cogent and approachable argument for a personal meditation practice based on secular Buddhist principles."[3]

Adam Frank, writing for National Public Radio, called it "delightfully personal, yet broadly important".[6]

The Washington Post gave a more mixed review, writing that "while [Wright] does not make a fully convincing case for some of his more grandiose claims about truth and freedom, his argument contains many interesting and illuminating points."[7]

In 2020, Evan Thompson questioned what he called Buddhist exceptionalism, "the belief that Buddhism is superior to other religions... or that Buddhism isn't really a religion but rather is a kind of 'mind science,' therapy, philosophy, or a way of life based on meditation."[8] Thompson questioned both Wright's version of secularized and naturalized Buddhism and, conversely, Wright's conception of evolutionary psychology that Wright claims Buddhism is uniquely equipped to address.[8]

References[edit]

- ^ Cowles, Gregory (18 August 2017). "A Science Writer Embraces Buddhism as a Path to Enlightenment". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Illing, Sean (12 October 2014). "Why Buddhism is true". Vox. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c "Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation | Kirkus Review". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Gopnik, Adam. "What Meditation Can Do for Us, and What It Can't". The New Yorker. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ Damasio, Antonio (7 August 2017). "Assessing the Value of Buddhism, for Individuals and for the World". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Frank, Adam. "Why 'Why Buddhism is True' is True". National Public Radio. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ Romeo, Nick (25 August 2017). "Meditation can make us happy, but can it also make us good?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Thompson, Evan (2020). Why I am Not a Buddhist. Yale University Press.

===

불교는 왜 진실인가

위키백과, 우리 모두의 백과사전.

불교는 왜 진실인가(부제: 명상과 깨달음의 과학)은 언론이이자 진화 심리학자인 로버트 라이트의 2017년 책이다. 2017년 8월 이 책은 논픽션 양장본 부문에서 뉴욕타임스 베스트셀러에서 4위를 기록했다.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

목차

1 내용

2 반응

2.1 긍정적

2.2 부정적

3 각주

내용

이 책에서, 로버트 라이트는 환생과 같은 초자연적 현상에 대한 믿음을 배제하고, 마음챙김 명상과 같은 세속적이고 서구화 된 불교 양식을 옹호한다. 그는 또한 명상의 보편화는 타인에 대한 감수성, 동정심, 공감을 일깨워 미국 사회 전반에 만연한 정치적 부족주의를 줄일 수 있다고 주장한다. 그는 또한 인간 고통의 원인에 대한 불교의 진단은 진화 생물학과 진화 심리학에 비춰볼 때 타당하다고 진단한다. 마음모듈이론과 불교의 가르침 중 무아론의 공통점 또한 집중적으로 다루고 있다.

반응

긍정적

“ 라이트의 책에는시나 역설이 없습니다. [...] 그러나 라이트가 당신에게 심오하거나 아름다운 것을 말하고 있다고 느끼지 않는다면 직접 연습과 모호하지 않고 직접 명상 연습을 통해 자신의 역사를 추적했습니다. 결국 그는 일주일에 걸친 퇴각과 불교 교리에 대한 강렬한 연구로 이어졌으며 불교 사상과 역사를 분명하게 만들어줍니다. ”

— Adam Gopnik의 뉴요커의 리뷰

“ 라이트의 책은 도발적이고 유익하며 많은 면에서 읽을만하다. ”

— 신경 과학자 안토니오 다 마시오

“ 세속적인 불교 원칙에 근거한 개인 명상 연습. ”

— Kirkus Reviews

“ 유쾌하고 개인적이지만 광범위하게 중요한 새 책 ”

— 미국 공영방송의 저술가 인 애덤 프랭크

“ 진실과 자유에 대한 그의 웅장한 주장을 라이트가 완전히 증명하는 것은 아니지만, 그의 주장에는 많은 흥미롭고 명민한 주장들이 포함되어있다. ”

— 워싱턴 포스트

부정적

에반 톰슨 (Evan Thompson)은 2020년에 라이트의 책이 담고 있는 불교예외주의에 대해 의문을 제기했다. 그에 따르면 불교예외주의는 불교가 다른 종교보다 우월하며 실제로 종교가 아니라 일종의 마음 과학, 치료, 철학이라는 주장이다. 톰슨은 라이트의 세속적이고 자연적 불교에 의문을 제기했으며, 과연 라이트의 말대로 불교만이 진화심리학을 독자적으로 설명할 수 있는지에 대해서도 회의감을 표현했다.

각주

- Cowles, Gregory (18 August 2017). "A Science Writer Embraces Buddhism as a Path to Enlightenment". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Illing, Sean (12 October 2014). "Why Buddhism is true". Vox. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation | Kirkus Review". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Gopnik, Adam. "What Meditation Can Do for Us, and What It Can't". The New Yorker. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Damasio, Antonio (7 August 2017). "Assessing the Value of Buddhism, for Individuals and for the World". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Frank, Adam. "Why 'Why Buddhism is True' is True". National Public Radio. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Romeo, Nick (25 August 2017). "Meditation can make us happy, but can it also make us good?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Thompson, Evan (2020). Why I am Not a Buddhist. Yale University Press.

분류: 불교진화생물학2017년 책

===

From one of America’s most brilliant writers, a New York Times bestselling journey through psychology, philosophy, and lots of meditation to show how Buddhism holds the key to moral clarity and enduring happiness.

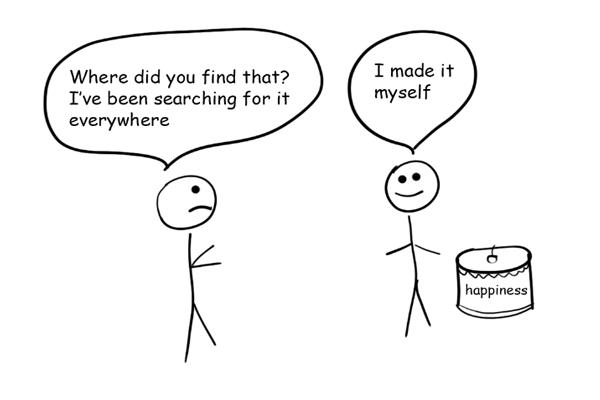

At the heart of Buddhism is a simple claim: The reason we suffer—and the reason we make other people suffer—is that we don’t see the world clearly. At the heart of Buddhist meditative practice is a radical promise: We can learn to see the world, including ourselves, more clearly and so gain a deep and morally valid happiness.

In this “sublime” (The New Yorker), pathbreaking book, Robert Wright shows how taking this promise seriously can change your life—how it can loosen the grip of anxiety, regret, and hatred, and how it can deepen your appreciation of beauty and of other people. He also shows why this transformation works, drawing on the latest in neuroscience and psychology, and armed with an acute understanding of human evolution.

This book is the culmination of a personal journey that began with Wright’s landmark book on evolutionary psychology, The Moral Animal, and deepened as he immersed himself in meditative practice and conversed with some of the world’s most skilled meditators. The result is a story that is “provocative, informative and...deeply rewarding” (The New York Times Book Review), and as entertaining as it is illuminating. Written with the wit, clarity, and grace for which Wright is famous,

Why Buddhism Is True lays the foundation for a spiritual life in a secular age and shows how, in a time of technological distraction and social division, we can save ourselves from ourselves, both as individuals and as a species.

===

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Why Buddhism is True

1

Taking the Red Pill

At the risk of overdramatizing the human condition: Have you ever seen the movie The Matrix?

It’s about a guy named Neo (played by Keanu Reeves), who discovers that he’s been inhabiting a dream world. The life he thought he was living is actually an elaborate hallucination. He’s having that hallucination while, unbeknownst to him, his actual physical body is inside a gooey, coffin-size pod—one among many pods, rows and rows of pods, each pod containing a human being absorbed in a dream. These people have been put in their pods by robot overlords and given dream lives as pacifiers.

The choice faced by Neo—to keep living a delusion or wake up to reality—is famously captured in the movie’s “red pill” scene. Neo has been contacted by rebels who have entered his dream (or, strictly speaking, whose avatars have entered his dream). Their leader, Morpheus (played by Laurence Fishburne), explains the situation to Neo: “You are a slave, Neo. Like everyone else, you were born into bondage, into a prison that you cannot taste or see or touch—a prison for your mind.” The prison is called the Matrix, but there’s no way to explain to Neo what the Matrix ultimately is. The only way to get the whole picture, says Morpheus, is “to see it for yourself.” He offers Neo two pills, a red one and a blue one. Neo can take the blue pill and return to his dream world, or take the red pill and break through the shroud of delusion. Neo chooses the red pill.

That’s a pretty stark choice: a life of delusion and bondage or a life of insight and freedom. In fact, it’s a choice so dramatic that you’d think a Hollywood movie is exactly where it belongs—that the choices we really get to make about how to live our lives are less momentous than this, more pedestrian. Yet when that movie came out, a number of people saw it as mirroring a choice they had actually made.

The people I’m thinking about are what you might call Western Buddhists, people in the United States and other Western countries who, for the most part, didn’t grow up Buddhist but at some point adopted Buddhism. At least they adopted a version of Buddhism, a version that had been stripped of some supernatural elements typically found in Asian Buddhism, such as belief in reincarnation and in various deities. This Western Buddhism centers on a part of Buddhist practice that in Asia is more common among monks than among laypeople: meditation, along with immersion in Buddhist philosophy. (Two of the most common Western conceptions of Buddhism—that it’s atheistic and that it revolves around meditation—are wrong; most Asian Buddhists do believe in gods, though not an omnipotent creator God, and don’t meditate.)

These Western Buddhists, long before they watched The Matrix, had become convinced that the world as they had once seen it was a kind of illusion—not an out-and-out hallucination but a seriously warped picture of reality that in turn warped their approach to life, with bad consequences for them and the people around them. Now they felt that, thanks to meditation and Buddhist philosophy, they were seeing things more clearly. Among these people, The Matrix seemed an apt allegory of the transition they’d undergone, and so became known as a “dharma movie.” The word dharma has several meanings, including the Buddha’s teachings and the path that Buddhists should tread in response to those teachings. In the wake of The Matrix, a new shorthand for “I follow the dharma” came into currency: “I took the red pill.”

I saw The Matrix in 1999, right after it came out, and some months later I learned that I had a kind of connection to it. The movie’s directors, the Wachowski siblings, had given Keanu Reeves three books to read in preparation for playing Neo. One of them was a book I had written a few years earlier, The Moral Animal: Evolutionary Psychology and Everyday Life.

I’m not sure what kind of link the directors saw between my book and The Matrix. But I know what kind of link I see. Evolutionary psychology can be described in various ways, and here’s one way I had described it in my book: It is the study of how the human brain was designed—by natural selection—to mislead us, even enslave us.

Don’t get me wrong: natural selection has its virtues, and I’d rather be created by it than not be created at all—which, so far as I can tell, are the two options this universe offers. Being a product of evolution is by no means entirely a story of enslavement and delusion. Our evolved brains empower us in many ways, and they often bless us with a basically accurate view of reality.

Still, ultimately, natural selection cares about only one thing (or, I should say, “cares”—in quotes—about only one thing, since natural selection is just a blind process, not a conscious designer). And that one thing is getting genes into the next generation. Genetically based traits that in the past contributed to genetic proliferation have flourished, while traits that didn’t have fallen by the wayside. And the traits that have survived this test include mental traits—structures and algorithms that are built into the brain and shape our everyday experience. So if you ask the question “What kinds of perceptions and thoughts and feelings guide us through life each day?” the answer, at the most basic level, isn’t “The kinds of thoughts and feelings and perceptions that give us an accurate picture of reality.” No, at the most basic level the answer is “The kinds of thoughts and feelings and perceptions that helped our ancestors get genes into the next generation.” Whether those thoughts and feelings and perceptions give us a true view of reality is, strictly speaking, beside the point. As a result, they sometimes don’t. Our brains are designed to, among other things, delude us.

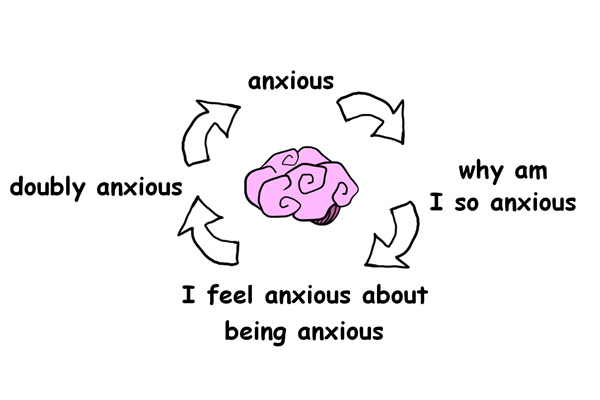

Not that there’s anything wrong with that! Some of my happiest moments have come from delusion—believing, for example, that the Tooth Fairy would pay me a visit after I lost a tooth. But delusion can also produce bad moments. And I don’t just mean moments that, in retrospect, are obviously delusional, like horrible nightmares. I also mean moments that you might not think of as delusional, such as lying awake at night with anxiety. Or feeling hopeless, even depressed, for days on end. Or feeling bursts of hatred toward people, bursts that may actually feel good for a moment but slowly corrode your character. Or feeling bursts of hatred toward yourself. Or feeling greedy, feeling a compulsion to buy things or eat things or drink things well beyond the point where your well-being is served.

Though these feelings—anxiety, despair, hatred, greed—aren’t delusional the way a nightmare is delusional, if you examine them closely, you’ll see that they have elements of delusion, elements you’d be better off without.

And if you think you would be better off, imagine how the whole world would be. After all, feelings like despair and hatred and greed can foster wars and atrocities. So if what I’m saying is true—if these basic sources of human suffering and human cruelty are indeed in large part the product of delusion—there is value in exposing this delusion to the light.

Sounds logical, right? But here’s a problem that I started to appreciate shortly after I wrote my book about evolutionary psychology: the exact value of exposing a delusion to the light depends on what kind of light you’re talking about. Sometimes understanding the ultimate source of your suffering doesn’t, by itself, help very much.

An Everyday Delusion

Let’s take a simple but fundamental example: eating some junk food, feeling briefly satisfied, and then, only minutes later, feeling a kind of crash and maybe a hunger for more junk food. This is a good example to start with for two reasons.

First, it illustrates how subtle our delusions can be. There’s no point in the course of eating a six-pack of small powdered-sugar doughnuts when you’re believing that you’re the messiah or that foreign agents are conspiring to assassinate you. And that’s true of many sources of delusion that I’ll discuss in this book: they’re more about illusion—about things not being quite what they seem—than about delusion in the more dramatic sense of that word. Still, by the end of the book, I’ll have argued that all of these illusions do add up to a very large-scale warping of reality, a disorientation that is as significant and consequential as out-and-out delusion.

The second reason junk food is a good example to start with is that it’s fundamental to the Buddha’s teachings. Okay, it can’t be literally fundamental to the Buddha’s teachings, because 2,500 years ago, when the Buddha taught, junk food as we know it didn’t exist. What’s fundamental to the Buddha’s teachings is the general dynamic of being powerfully drawn to sensory pleasure that winds up being fleeting at best. One of the Buddha’s main messages was that the pleasures we seek evaporate quickly and leave us thirsting for more. We spend our time looking for the next gratifying thing—the next powdered-sugar doughnut, the next sexual encounter, the next status-enhancing promotion, the next online purchase. But the thrill always fades, and it always leaves us wanting more. The old Rolling Stones lyric “I can’t get no satisfaction” is, according to Buddhism, the human condition. Indeed, though the Buddha is famous for asserting that life is pervaded by suffering, some scholars say that’s an incomplete rendering of his message and that the word translated as “suffering,” dukkha, could, for some purposes, be translated as “unsatisfactoriness.”

So what exactly is the illusory part of pursuing doughnuts or sex or consumer goods or a promotion? There are different illusions associated with different pursuits, but for now we can focus on one illusion that’s common to these things: the overestimation of how much happiness they’ll bring. Again, by itself this is delusional only in a subtle sense. If I asked you whether you thought that getting that next promotion, or getting an A on that next exam, or eating that next powdered-sugar doughnut would bring you eternal bliss, you’d say no, obviously not. On the other hand, we do often pursue such things with, at the very least, an unbalanced view of the future. We spend more time envisioning the perks that a promotion will bring than envisioning the headaches it will bring. And there may be an unspoken sense that once we’ve achieved this long-sought goal, once we’ve reached the summit, we’ll be able to relax, or at least things will be enduringly better. Similarly, when we see that doughnut sitting there, we immediately imagine how good it tastes, not how intensely we’ll want another doughnut only moments after eating it, or how we’ll feel a bit tired or agitated later, when the sugar rush subsides.

Why Pleasure Fades

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to explain why this sort of distortion would be built into human anticipation. It just takes an evolutionary biologist—or, for that matter, anyone willing to spend a little time thinking about how evolution works.

Here’s the basic logic. We were “designed” by natural selection to do certain things that helped our ancestors get their genes into the next generation—things like eating, having sex, earning the esteem of other people, and outdoing rivals. I put “designed” in quotation marks because, again, natural selection isn’t a conscious, intelligent designer but an unconscious process. Still, natural selection does create organisms that look as if they’re the product of a conscious designer, a designer who kept fiddling with them to make them effective gene propagators. So, as a kind of thought experiment, it’s legitimate to think of natural selection as a “designer” and put yourself in its shoes and ask: If you were designing organisms to be good at spreading their genes, how would you get them to pursue the goals that further this cause? In other words, granted that eating, having sex, impressing peers, and besting rivals helped our ancestors spread their genes, how exactly would you design their brains to get them to pursue these goals? I submit that at least three basic principles of design would make sense:

1. Achieving these goals should bring pleasure, since animals, including humans, tend to pursue things that bring pleasure.

2. The pleasure shouldn’t last forever. After all, if the pleasure didn’t subside, we’d never seek it again; our first meal would be our last, because hunger would never return. So too with sex: a single act of intercourse, and then a lifetime of lying there basking in the afterglow. That’s no way to get lots of genes into the next generation!

3. The animal’s brain should focus more on (1), the fact that pleasure will accompany the reaching of a goal, than on (2), the fact that the pleasure will dissipate shortly thereafter. After all, if you focus on (1), you’ll pursue things like food and sex and social status with unalloyed gusto, whereas if you focus on (2), you could start feeling ambivalence. You might, for example, start asking what the point is of so fiercely pursuing pleasure if the pleasure will wear off shortly after you get it and leave you hungering for more. Before you know it, you’ll be full of ennui and wishing you’d majored in philosophy.

If you put these three principles of design together, you get a pretty plausible explanation of the human predicament as diagnosed by the Buddha. Yes, as he said, pleasure is fleeting, and, yes, this leaves us recurrently dissatisfied. And the reason is that pleasure is designed by natural selection to evaporate so that the ensuing dissatisfaction will get us to pursue more pleasure. Natural selection doesn’t “want” us to be happy, after all; it just “wants” us to be productive, in its narrow sense of productive. And the way to make us productive is to make the anticipation of pleasure very strong but the pleasure itself not very long-lasting.

Scientists can watch this logic play out at the biochemical level by observing dopamine, a neurotransmitter that is correlated with pleasure and the anticipation of pleasure. In one seminal study, they took monkeys and monitored dopamine-generating neurons as drops of sweet juice fell onto the monkeys’ tongues. Predictably, dopamine was released right after the juice touched the tongue. But then the monkeys were trained to expect drops of juice after a light turned on. As the trials proceeded, more and more of the dopamine came when the light turned on, and less and less came after the juice hit the tongue.

We have no way of knowing for sure what it felt like to be one of those monkeys, but it would seem that, as time passed, there was more in the way of anticipating the pleasure that would come from the sweetness, yet less in the way of pleasure actually coming from the sweetness.I,† To translate this conjecture into everyday human terms:

If you encounter a new kind of pleasure—if, say, you’ve somehow gone your whole life without eating a powdered-sugar doughnut, and somebody hands you one and suggests you try it—you’ll get a big blast of dopamine after the taste of the doughnut sinks in. But later, once you’re a confirmed powdered-sugar-doughnut eater, the lion’s share of the dopamine spike comes before you actually bite into the doughnut, as you’re staring longingly at it; the amount that comes after the bite is much less than the amount you got after that first, blissful bite into a powdered-sugar doughnut. The pre-bite dopamine blast you’re now getting is the promise of more bliss, and the post-bite drop in dopamine is, in a way, the breaking of the promise—or, at least, it’s a kind of biochemical acknowledgment that there was some overpromising. To the extent that you bought the promise—anticipated greater pleasure than would be delivered by the consumption itself—you have been, if not deluded in the strong sense of that term, at least misled.

Kind of cruel, in a way—but what do you expect from natural selection? Its job is to build machines that spread genes, and if that means programming some measure of illusion into the machines, then illusion there will be.

Unhelpful Insights

So this is one kind of light science can shed on an illusion. Call it “Darwinian light.” By looking at things from the point of view of natural selection, we see why the illusion would be built into us, and we have more reason than ever to see that it is an illusion. But—and this is the main point of this little digression—this kind of light is of limited value if your goal is to actually liberate yourself from the illusion.

Don’t believe me? Try this simple experiment: (1) Reflect on the fact that our lust for doughnuts and other sweet things is a kind of illusion—that the lust implicitly promises more enduring pleasure than will result from succumbing to it, while blinding us to the letdown that may ensue. (2) As you’re reflecting on this fact, hold a powdered-sugar doughnut six inches from your face. Do you feel the lust for it magically weakening? Not if you’re like me, no.

This is what I discovered after immersing myself in evolutionary psychology: knowing the truth about your situation, at least in the form that evolutionary psychology provides it, doesn’t necessarily make your life any better. In fact, it can actually make it worse. You’re still stuck in the natural human cycle of ultimately futile pleasure-seeking—what psychologists sometimes call “the hedonic treadmill”—but now you have new reason to see the absurdity of it. In other words, now you see that it’s a treadmill, a treadmill specifically designed to keep you running, often without really getting anywhere—yet you keep running!

And powdered-sugar doughnuts are just the tip of the iceberg. I mean, the truth is, it’s not all that uncomfortable to be aware of the Darwinian logic behind your lack of dietary self-discipline. In fact, you may find in this logic a comforting excuse: it’s hard to fight Mother Nature, right? But evolutionary psychology also made me more aware of how illusion shapes other kinds of behavior, such as the way I treat other people and the way I, in various senses, treat myself. In these realms, Darwinian self-consciousness was sometimes very uncomfortable.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, a meditation teacher in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, has said, “Ultimately, happiness comes down to choosing between the discomfort of becoming aware of your mental afflictions and the discomfort of being ruled by them.” What he meant is that if you want to liberate yourself from the parts of the mind that keep you from realizing true happiness, you have to first become aware of them, which can be unpleasant.

Okay, fine; that’s a form of painful self-consciousness that would be worthwhile—the kind that leads ultimately to deep happiness. But the kind I got from evolutionary psychology was the worst of both worlds: the painful self-consciousness without the deep happiness. I had both the discomfort of being aware of my mental afflictions and the discomfort of being ruled by them.

Jesus said, “I am the way and the truth and the life.” Well, with evolutionary psychology I felt I had found the truth. But, manifestly, I had not found the way. Which was enough to make me wonder about another thing Jesus said: that the truth will set you free. I felt I had seen the basic truth about human nature, and I saw more clearly than ever how various illusions imprisoned me, but this truth wasn’t amounting to a Get Out of Jail Free card.

So is there another version of the truth out there that would set me free? No, I don’t think so. At least, I don’t think there’s an alternative to the truth presented by science; natural selection, like it or not, is the process that created us. But some years after writing The Moral Animal, I did start to wonder if there was a way to operationalize the truth—a way to put the actual, scientific truth about human nature and the human condition into a form that would not just identify and explain the illusions we labor under but would also help us liberate ourselves from them. I started wondering if this Western Buddhism I was hearing about might be that way. Maybe many of the Buddha’s teachings were saying essentially the same thing modern psychological science says. And maybe meditation was in large part a different way of appreciating these truths—and, in addition, a way of actually doing something about them.

So in August 2003 I headed to rural Massachusetts for my first silent meditation retreat—a whole week devoted to meditation and devoid of such distractions as email, news from the outside world, and speaking to other human beings.

The Truth about Mindfulness

You could be excused for doubting that a retreat like this would yield anything very dramatic or profound. The retreat was, broadly speaking, in the tradition of “mindfulness meditation,” the kind of meditation that was starting to catch on in the West and that in the years since has gone mainstream. As commonly described, mindfulness—the thing mindfulness meditation aims to cultivate—isn’t very deep or exotic. To live mindfully is to pay attention to, to be “mindful of” what’s happening in the here and now and to experience it in a clear, direct way, unclouded by various mental obfuscations. Stop and smell the roses.

This is an accurate description of mindfulness as far as it goes. But it doesn’t go very far. “Mindfulness,” as popularly conceived, is just the beginning of mindfulness.

And it’s in some ways a misleading beginning. If you delve into ancient Buddhist writings, you won’t find a lot of exhortations to stop and smell the roses—and that’s true even if you focus on those writings that feature the word sati, the word that’s translated as “mindfulness.” Indeed, sometimes these writings seem to carry a very different message. The ancient Buddhist text known as The Four Foundations of Mindfulness—the closest thing there is to a Bible of Mindfulness—reminds us that our bodies are “full of various kinds of unclean things” and instructs us to meditate on such bodily ingredients as “feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, skin-oil, saliva, mucus, fluid in the joints, urine.” It also calls for us to imagine our bodies “one day, two days, three days dead—bloated, livid, and festering.”

I’m not aware of any bestselling books on mindfulness meditation called Stop and Smell the Feces. And I’ve never heard a meditation teacher recommend that I meditate on my bile, phlegm, and pus or on the rotting corpse that I will someday be. What is presented today as an ancient meditative tradition is actually a selective rendering of an ancient meditative tradition, in some cases carefully manicured.

There’s no scandal here. There’s nothing wrong with modern interpreters of Buddhism being selective—even, sometimes, creative—in what they present as Buddhism. All spiritual traditions evolve, adapting to time and place, and the Buddhist teachings that find an audience today in the United States and Europe are a product of such evolution.

The main thing, for our purposes, is that this evolution—the evolution that has produced a distinctively Western, twenty-first-century version of Buddhism—hasn’t severed the connection between current practice and ancient thought. Modern mindfulness meditation isn’t exactly the same as ancient mindfulness meditation, but the two share a common philosophical foundation. If you follow the underlying logic of either of them far enough, you will find a dramatic claim: that we are, metaphorically speaking, living in the Matrix. However mundane mindfulness meditation may sometimes sound, it is a practice that, if pursued rigorously, can let you see what Morpheus says the red pill will let you see. Namely, “how deep the rabbit hole goes.”

On that first meditation retreat, I had some pretty powerful experiences—powerful enough to make me want to see just how deep the rabbit hole goes. So I read more about Buddhist philosophy, and talked to experts on Buddhism, and eventually went on more meditation retreats, and established a daily meditation practice.

All of this made it clearer to me why The Matrix had come to be known as a “dharma movie.” Though evolutionary psychology had already convinced me that people are by nature pretty deluded, Buddhism, it turned out, painted an even more dramatic picture. In the Buddhist view, the delusion touches everyday perceptions and thoughts in ways subtler and more pervasive than I had imagined. And in ways that made sense to me. In other words, this kind of delusion, it seemed to me, could be explained as the natural product of a brain that had been engineered by natural selection. The more I looked into Buddhism, the more radical it seemed, but the more I examined it in the light of modern psychology, the more plausible it seemed. The real-life Matrix, the one in which we’re actually embedded, came to seem more like the one in the movie—not quite as mind-bending, maybe, but profoundly deceiving and ultimately oppressive, and something that humanity urgently needs to escape.

The good news is the other thing I came to believe: if you want to escape from the Matrix, Buddhist practice and philosophy offer powerful hope. Buddhism isn’t alone in this promise. There are other spiritual traditions that address the human predicament with insight and wisdom. But Buddhist meditation, along with its underlying philosophy, addresses that predicament in a strikingly direct and comprehensive way. Buddhism offers an explicit diagnosis of the problem and a cure. And the cure, when it works, brings not just happiness but clarity of vision: the actual truth about things, or at least something way, way closer to that than our everyday view of them.

Some people who have taken up meditation in recent years have done so for essentially therapeutic reasons. They practice mindfulness-based stress reduction or focus on some specific personal problem. They may have no idea that the kind of meditation they’re practicing can be a deeply spiritual endeavor and can transform their view of the world. They are, without knowing it, near the threshold of a basic choice, a choice that only they can make. As Morpheus says to Neo, “I can only show you the door. You’re the one that has to walk through it.” This book is an attempt to show people the door, give them some idea of what lies beyond it, and explain, from a scientific standpoint, why what lies beyond it has a stronger claim to being real than the world they’re familiar with.

I. This and all subsequent daggers refer to elaborative notes that can be found in the Notes section at the end of the book. --This text refers to the paperback edition. About the Author

Robert Wright is the New York Times bestselling author of The Evolution of God (a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize), Nonzero, The Moral Animal, Three Scientists and their Gods (a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award), and Why Buddhism Is True. He is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of the widely respected Bloggingheads.tv and MeaningofLife.tv. He has written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New York Times, Time, Slate, and The New Republic. He has taught at the University of Pennsylvania and at Princeton University, where he also created the popular online course “Buddhism and Modern Psychology.” He is currently Visiting Professor of Science and Religion at Union Theological Seminary in New York. --This text refers to the paperback edition. =============================

Review

"I have been waiting all my life for a readable, lucid explanation of Buddhism by a tough-minded, skeptical intellect. Here it is. This is a scientific and spiritual voyage unlike any I have taken before."

--Martin Seligman, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and bestselling author of Authentic Happiness

"This is exactly the book that so many of us are looking for. Writing with his characteristic wit, brilliance, and tenderhearted skepticism, Robert Wright tells us everything we need to know about the science, practice, and power of Buddhism."

--Susan Cain, bestselling author of Quiet<br ><br >

"Robert Wright brings his sharp wit and love of analysis to good purpose, making a compelling case for the nuts and bolts of how meditation actually works. This book will be useful for all of us, from experienced meditators to hardened skeptics who are wondering what all the fuss is about."

--Sharon Salzberg, cofounder of the Insight Meditation Society and bestselling author of Real Happiness

<br ><br >"What happens when someone steeped in evolutionary psychology takes a cool look at Buddhism? If that person is, like Robert Wright, a gifted writer, the answer is this surprising, enjoyable, challenging, and potentially life-changing book."

--Peter Singer, professor of philosophy at Princeton University and author of Ethics in the Real World<br ><br >

"Joyful and insightful... both entertaining and informative."

--Publishers Weekly (starred review)<br ><br >

"A well-organized, freshly conceived introduction to core concepts of Buddhist thought.... Wright lightens the trek through some challenging philosophical concepts with well-chosen anecdotes and a self-deprecating humor."

--Kirkus Reviews<br ><br

"A sublime achievement."

--Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker<br ><br >

"Cool, rational, and dryly cynical, Robert Wright is an unlikely guide to the Dharma and 'not-self.' But in this extraordinary book, he makes a powerful case for a Buddhist way of life and a Buddhist view of the mind. With great clarity and wit, he brings together personal anecdotes with insights from evolutionary theory and cognitive science to defend an ancient yet radical world-view. This is a truly transformative work."

--Paul Bloom, professor of psychology at Yale University and author of Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion

"What a terrific book. The combination of evolutionary psychology, philosophy, astute readings of Buddhist tradition, and personal meditative experience is absolutely unique and clarifying."

--Jonathan Gold, professor of religion at Princeton University and author of Paving the Great Way: Vasubandhu's Unifying Buddhist Philosophy

"Regardless of their own religious or spiritual roots, many open-minded readers who accompany [Wright] on this journey will find themselves agreeing with him."

--Shelf Awareness --This text refers to the audioCD edition.Review

“A sublime achievement.”

―Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker

“Provocative, informative and... deeply rewarding.... I found myself not just agreeing [with] but applauding the author.”

―The New York Times Book Review

“This is exactly the book that so many of us are looking for. Writing with his characteristic wit, brilliance, and tenderhearted skepticism, Robert Wright tells us everything we need to know about the science, practice, and power of Buddhism.”

―Susan Cain, bestselling author of Quiet

“I have been waiting all my life for a readable, lucid explanation of Buddhism by a tough-minded, skeptical intellect. Here it is. This is a scientific and spiritual voyage unlike any I have taken before.”

―Martin Seligman, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and bestselling author of Authentic Happiness

“A fantastically rational introduction to meditation…. It constantly made me smile a little, and occasionally chuckle…. A wry, self-deprecating, and brutally empirical guide to the avoidance of suffering.”

―Andrew Sullivan, New York Magazine

“[A] superb, level-headed new book.”

―Oliver Burkeman, The Guardian

“Robert Wright brings his sharp wit and love of analysis to good purpose, making a compelling case for the nuts and bolts of how meditation actually works. This book will be useful for all of us, from experienced meditators to hardened skeptics who are wondering what all the fuss is about.”

―Sharon Salzberg, cofounder of the Insight Meditation Society and bestselling author of Real Happiness

“What happens when someone steeped in evolutionary psychology takes a cool look at Buddhism? If that person is, like Robert Wright, a gifted writer, the answer is this surprising, enjoyable, challenging, and potentially life-changing book.”

―Peter Singer, professor of philosophy at Princeton University and author of Ethics in the Real World

“Delightfully personal, yet broadly important.”

―NPR

“Rendered in a down-to-earth and highly readable style, with witty quips and self-effacing humility that give the book its distinctive appeal and persuasive power.”

―America Magazine --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

=============

From Australia

Gina

3.0 out of 5 stars Oscillating thoughts

Reviewed in Australia on 8 January 2018

Verified Purchase

From the onset, I immediately liked what I was reading, but as I progressed further and further into the book, I started losing interest. This is not to discount the author and his superior knowledge on this subject, with all due respect, but more about my mindset at the time of reading this book.

Let me explain.

I'm by no means an expert on meditation or on any science around the philosophy of meditation and enlightenment, so my boredom came about because I felt like I'd acquired this knowledge before, either through having read similar, or from having explored meditation in my earlier life (this sounds arrogant of me, but I promise you, it's not intended to sound like that at all), and because the author tended to sermonise too much, in my opinion, which I found very annoying.

I think that the minute I realised this about the book, is about the time that I simply switched off and lost interest, but regardless, I still read it to the end, because I don't like leaving books unfinished and at least wanted to give the author the due respect to read his book to the end.

Having said this, there were bits in the book that resonated with me, especially because it seemed 'common core' as the author puts it. The bits where he speaks of questioning an emotion and getting an answer, and suddenly the emotion is gone! I've done this many times before in the course of my entire life, and I was thrilled that the author had also had this experience. An example of this experience would be in which I'd suddenly be in a situation where I'd placed a judgement call (be it subconsciously) of someone new to me, and because of that judgement call, I'd find myself feeling aggravated, only to then realise in an instant that I'm feeling this way and to check-in with myself and ask the magic question, why? Why am I feeling this way about that person? And as soon as I'd get my answer, it's like an epiphany and the sky opens up and the angels in the universe are all suddenly playing a harp together, and instantly, whatever feelings and thoughts I had of that person, positive or negative, it's gone.

Other than that, the other stuff in his book, was 'common core,' stuff that you may already know and may have tried before, such as; meditate. Still the mind. Feel the emptiness. Know you are nothing and simultaneously know that you are something, that is in the here and now, forever more. Easy done for some of us, but not so easy for some of us. For me. What can I say? I'm here, right now. My mind is actively active, but can be a blank as I focus on my breath or focus on simply being.

You get the gist.

2 people found this helpful

Helpful

Report abuse

Scott K

5.0 out of 5 stars A book for everyone

Reviewed in Australia on 21 July 2020

Verified Purchase

Although I have been meditating and reaping the rewards for year, little did I know that if I improved my technique, the benefits would double.

This book taught me how to improve my technique and reap the benefits.

It's easy reading and even if you have no interest in Buddhism, it's much more about that.

It teaches how ’not to take anything for granted’ wonderful whether you are a meditater like me, or for someone who just needs a little assistance getting out of the daily anxieties and potholes we find ourselves in.

Helpful

Report abuse

David N, Canberra, Australia

4.0 out of 5 stars Ignore the title - a secular investigation of western Buddhism psychology and why meditation helps

Reviewed in Australia on 6 March 2020

Verified Purchase

Not-self – the idea that there is no executive function within our conscious mind – the self is an illusion as we react to many stimuli within our minds, esp feelings. The best given example is jealousy, when it arises and we are not in control.

Robert Wright “Budhhism is right” – (you have to get beyond the awful title!) His position is that modern and esp evolutionary psychology accords with Buddha on much of this (so what), and that mindful meditation can help get some measure of clarity..

Seemingly knowledgeable and uses lots of citations (haven't investigated how credible they are, but presented as eminent psychologists and taken on trust). His delivery is a little flippant and irreverent to a degree – so easy to read and amusing at times.

Helpful

Report abuse

enrico

2.0 out of 5 stars I was waiting for this book like a kid waiting for a lolly

Reviewed in Australia on 27 June 2018

Verified Purchase

I was waiting for this book like a kid waiting for a lolly.

and always when you image something big, reality is different..from the title, i was expect a book that can open my mind, with scientific proof about Buddhism, and the why, the book is very hard to understand ( i'm not english native), and very very boring about personal history, personal fact from the past, so he became heavier and heavier, i didn't finished it, but i was expecting something more focus on why, examples, studies, scientific way plus personal experience. i found other book much more interesting than this one.

3 people found this helpful

Helpful

Report abuse

meditatecreate

5.0 out of 5 stars An absolutely brilliant book. A thorough and entertaining dissertation on Buddhism ...

Reviewed in Australia on 10 February 2018

Verified Purchase

An absolutely brilliant book. A thorough and entertaining dissertation on Buddhism in a way that is accessible to those who are not Buddhist. Wright is a captivating writer. This book is a must read.

One person found this helpful

Helpful

Report abuse

Claire Martenson

5.0 out of 5 stars Very interesting

Reviewed in Australia on 23 December 2019

Verified Purchase

SO interesting. Love this book. I have suggested this to many friends

Helpful

Report abuse

Geoffrey

5.0 out of 5 stars Best Buddhism book I've read for a long time

Reviewed in Australia on 13 February 2018

Verified Purchase

Best Buddhism book I've read for a long time. But you have to take time, trying to understand the influenced of Western psychology and Buddhism can be difficult. He is a great writer. Read The Moral Animal also.

Helpful

Report abuse

From other countries

Andrew G. Marshall

4.0 out of 5 stars Emptiness and Not-Self Two Buddhist ideas and how they could change your life

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 15 January 2018

Verified Purchase

We see the world through the distorting lens of natural selection - that's the central idea in Wright's enlightening book - but what is good for getting our genes passed onto the next generation (all that natural selection cares about) does not necessarily make for the good life. However, many centuries ago Buddhism came up with a way to look beyond our knee jerk reactions of attraction and repulsion. It is called mindfulness meditation and Wright adds modern knowledge from neuroscience and psychology to show how we can have a truer sense of our best interests and thereby gain more self-control.

In particular, he is interested in two Buddhist concepts: not self and emptiness. Incidentally, these are two ideas I have long struggled with... Let's start with emptiness because Wright helped me finally nail this idea. Although we see, for example, our home as the source of security, continuity and lots of warm feelings associated with family, it is really just a pile of bricks and mortar. In the Buddhist sense it is an empty concept onto which we have projected all these emotions. Sure, our home evokes lots of strong reaction but a passing stranger would just see a house and react to the architecture or the location - which once again carries various cultural projections about whether a detached house is better than a semi-detached and how close it is to shops or how remote (which are all equally arbitrary criteria). As a therapist, I'm used to the concept that nothing is inherently good or bad but coloured by how we marshal our experiences, our prejudices and our expectations.

So good so far... but not-self is a much tougher idea. What I did find interesting is that Wright scuppers the idea of self as CEO which sits somewhere inside us and decides rationally what actions to take. Instead he uses neuroscience to explain that we have various modules that take charge. Rather than fighting temptation - for example to eat high sugar and fat foods - he suggests using the acronym: RAIN. Recognise the feeling, Accept it, Investigate the feeling and finally - the hard bit but meditation apparently helps - to Non-identify with the feeling and have Non-attachment to it. In this way the urge is allowed to form but does not get constantly re-inforced by the short term pleasure of, for example, eating the cake. Thus the link to the reward is broken and although the urge might still blossom without gratification it reduces and ultimately subsides.

The downside to this book is that Wright - like the majority of us - is a relative beginner to meditation and when it comes to seeking clarifications about Buddhism and enlightenment, he has to interview people further along the road. My suspicion is he often hears what he wants to hear, simplifying the arguments and glossing over the complexities of his case. Having said that I am convinced that I need to meditate more and take on board the concept of emptiness - because it is my attachment to particular things and outcomes which is often the source of so my unhappiness.

A useful book that I will stay with me for a long time and I recommend to others who want to take the red pill and see the 'truth'.

83 people found this helpful

Report abuse

Matt Mills

5.0 out of 5 stars One of the best books I've read

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 3 March 2019

Verified Purchase

As someone who's a scientist but also has an interest in secular buddhism, this book is amazing and I can't recommend it enough. Wright does a great job of taking you on a journey of logic, not for the purpose of converting anyone to a buddhist way of thinking, but just to simply show that the buddha's philosophy makes a lot of sense. The buddha made observations about human psychology thousands of years ago, and Wright excellently puts that into the context of modern living.

14 people found this helpful

Report abuse

Andrew Bill

5.0 out of 5 stars Brilliant, prepare to start being challenged.

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 25 December 2017

Verified Purchase

Just read Evolutionary Psychology by David Buss and as I have been trying to understand Buddhism for 50 years or so, I wondered how the two related to each other. The net immediately identified Why Buddhism is True and the rather brave author delivered abundantly. He confirmed the idea that dukkha as interpreted as unsatisfactoriness would enhance survival to reproduce. Mr Wright's honest description of his experiences during meditation are very helpful. He clarified the emptiness/formless ideas and helped me understand 'conditioning' very clearly. His discussion of no self enabled me to identify two slightly different points of view, one where the thoughts and feelings are not part of you which is his point of view, and the other where the thoughts and feelings are part of you, but not all of you, which I lean towards. Perhaps the other aspect he clarified that the word attachment could, depending on context, mean being 'lost in thought' i.e. conscious awareness being entrained in the thought stream as opposed to the mindfulness observation of the thought stream, is related to the two points of view about no self. His discussion about how the loving kindness towards all sentient beings could arise was not convincing to me, and would obviously be a great step towards avoiding conflict, but if we did see through the little tricks natural selection has programmed into us we may stop reproducing.

15 people found this helpful

Report abuse

From other countries

MT

5.0 out of 5 stars Don’t Miss this Superb Book...

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 20 February 2019

Verified Purchase

This book is very different (in a good way) to many on Buddhism because it dares to approach the subject from some unique and intriguing perspectives that I suspect will thoroughly enthral you.

While my Favourite Book on Eastern Philosophy / Religion remains Freedom From the Know (by that acknowledge Master Krishnamurti) the Book under review is now firmly in my Top 3 Sharing a shelf with the aforesaid, and with Eckhart Tolle’s Power of Now.

To share bookshelf space with Krishnamurti and Eckhart Tolle, you’ve really got to deliver something special - this book most definitely does! Think you’ll love it.

11 people found this helpful

Report abuse

Dennis Farcinsen Leth

5.0 out of 5 stars Buddhism and modern psychology.

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 13 October 2020

Verified Purchase

This is an amazing book that tries to unveil why buddhism is true. I started reading the book with a little background from various mindfullness and meditation books and as an experienced meditator.

It's a great book and it reaches some of the same conclusions as prof. Peter Elsass did in my native danish language. Modern western world can learn a lot from buddhism in ways that would bring our mental state in balance (if it is in unbalance).

The book is written with enormous insight into meditation, buddhism and psychology.

Sometimes Robert gets a little bit to educating and 'know it all' but that actually suits this book.

I can highly recommend it.

4 people found this helpful

Report abuse

Tham Chee Wah

5.0 out of 5 stars A breakdown of an illusive concept

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 24 September 2019

Verified Purchase

For someone who would like to have the illusive meditation dissected and explained, this is the go-to book. The theories are being structured and explained with insights and laid out in their simplest form.

Pick this up if you’ve doubts about meditation. In this book’s context, the author uses his own meditation experiences and encounters to bring readers to at least understand that the actions or inactions will lead to a blissful awareness. In this book, the author talks about the Buddhist meditation practice.

A lively and genuine experience-to-conceptual presentation of a daily practice, when done conscientiously, liberates the mind. For any novice, first timer, even a doubter, the message from this book is - why not? Try it.

For me, I’ve been doing daily meditation for decades. I truly appreciate the author’s work, beautiful, genuine and touching.

4 people found this helpful

Report abuse

TimG7

3.0 out of 5 stars Disappointed

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 12 August 2020

Verified Purchase

Disappointed. The reviews suggested almost a life changing read. It started very well. As the book progressed I switched off. I felt it was over complicated in parts and explanations could of been clearer and shorter. If you are looking at an introduction to Buddhism I wouldnt suggest this as a starting point. It was like reading a book by someone who never quite gets to the point until the last minute. I try very hard to focus on the positives but it felt like the author was trying to make the subject over intellectual in his presentation. Less is more.

3 people found this helpful

Report abuse

savagegardener

3.0 out of 5 stars Unsatisfying Mishmash.

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 24 January 2021

Verified Purchase

After reading any book, I spend some time asking myself if I learnt anything useful from it, or if it made me look at the world in a way that I hadn't considered before, and in this case the answers to both these questions is a resounding "no". The trouble is that this attempt by an academic, who happens to have dipped his toes in a bit of meditation, to then try and pull together strands of philosophy, science, and various flavours of Buddhism into a coherent whole is a complete failure. In the realms of the spiritual and the mystical, logic , and dissection by the intellect , rarely, if ever, will arrive at the truth. The book has interesting parts, but at times it's simply too long winded, and in the end it was a relief to finish it. For any serious spiritual seeker, I strongly recommend reading and watching the work of Eckhart Tolle or Sadhguru, or lesser known teachings from Robert Goodwin. If you want science, go to a scientist, if you want spirituality go to the great spiritual teachers of our time. If you want a wishy washy soup of both that satisfies neither appetite, read this.

One person found this helpful

Report abuse

J. Morgan

1.0 out of 5 stars Became annoying.

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 5 January 2021

Verified Purchase

This if course may just be me as a lot of things in my life start out OK but end up being annoying (I'll introduce you to a string of my X's one day if you like).

Take this sentence: "I don't know from first hand experience what it would be like to take LSD and follow it with a heroin chaser..." But guess what? Within one sentence he's off comparing this imaginary experience that he's never had - to one he HAS had meditating. Huh? It's all a bit like that. And it's all a bit 'let's sit down and me explain how to be happy'. Really? Basically he's a bit of a bliss ninny. Looking for permanent happiness. Never a good idea that.

Up to you but I'd save my money if I knew now what I didn't know then.

One person found this helpful

Report abuse

(Who knows)

5.0 out of 5 stars Loved it! Thought provoking.

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 25 November 2018

Verified Purchase

The book got me thinking. Always a good sign from a book.

I also agree with the title of the book (Though it does come across as arrogant). If any spiritual movement has got it right, Buddhism has got the closest in my honest opinion. The book describes a grown up version of spirituality thats not stuck in the middle ages and actually encourages you to use and master your mind (rather than shutting it down and believing what you are told to believe).

Most recommended from me!

5 people found this helpful

Report abuse

Thomas H.

3.0 out of 5 stars More the science of meditation than a real discussion on buddhism

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 25 April 2020

Verified Purchase

A largely average book on Buddhism. I think the naming is largely wrong. It's a good book if you want the health benefits of meditation and the health benefits of 'buddhism,' which the book oversimplifies to the point where it ignores the spirituality Buddhism entails but not good if you actually want to discover more about buddhism as I did. Maybe not a fault of the book, but perhaps a mis-advertisment.

2 people found this helpful

Report abuse

MikeW

1.0 out of 5 stars Uninspiring and boring.

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 31 December 2020

Verified Purchase

This book started off with a lot of promise, relating our natural reactions to evolution. I was hoping for some useful insights. However after a while I found it became tedious and I lost interest. It became so boring that I struggled to get to the end. It didn't seem to progress and it certainly didn't attract me to Buddhism at all. The tenets of Buddhism are far too vague and difficult to understand and frankly don't make sense. If you are looking for some inspiration or a way to help you cope with problems I advise you to give this a miss.

Report abuse

Paulo

5.0 out of 5 stars Good mix of science and faith ...

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 10 February 2021

Verified Purchase

If of course, faith is the right word...

I listened to the audio book, as is almost always the case the audio was off putting at times, because I am from the UK not the USA and we are different. I gave five stars because in the end all the distracting language, phrasing and accent didn't matter. I learned and developed from reading this book and I will go back to it time and again.

Report abuse

===

=======

A Critic at LargeAugust 7 & 14, 2017 Issue

What Meditation Can Do for Us, and What It Can’t

Examining the science and supernaturalism of Buddhism.

By Adam Gopnik

July 31, 2017

An author owns a snappy title, and then the snappy title owns the author. Robert Wright, having titled his new book “Why Buddhism Is True,” has to offer a throat-clearing preface and later an apologetic appendix, in order to explain exactly what he means by “Buddhism” and exactly what he means by “true,” while the totality of his book is an investigation into why we think there are “whys” in the world, and whether or not anything really “is.” Wright sets out to provide an unabashedly American answer to all these questions. He thinks that Buddhism is true in the immediate sense that it is helpful and therapeutic, and, by offering insights into our habitual thoughts and cravings, shows us how to fix them. Being Buddhist—that is, simply practicing Vipassana, or “insight” meditation—will make you feel better about being alive, he believes, and he shows how you can and why it does.

Robert Wright argues for meditation as a fully secular form of psychotherapy.

Robert Wright argues for meditation as a fully secular form of psychotherapy.Illustration by Anne Laval

Wright’s is a Buddhism almost completely cleansed of supernaturalism. His Buddha is conceived as a wise man and self-help psychologist, not as a divine being—no miraculous birth, no thirty-two distinguishing marks of the godhead (one being a penis sheath), no reincarnation. This is a pragmatic Buddhism, and Wright’s pragmatism, as in his previous books, can touch the edge of philistinism. Nearly all popular books about Buddhism are rich in poetic quotation and arresting aphorisms, those ironic koans that are part of the (Zen) Buddhist décor—tales of monks deciding that it isn’t the wind or the flag that’s waving in the breeze but only their minds. Wright’s book has no poetry or paradox anywhere in it. Since the poetic-comic side of Buddhism is one of its most appealing features, this leaves the book a little short on charm. Yet, if you never feel that Wright is telling you something profound or beautiful, you also never feel that he is telling you something untrue. Direct and unambiguous, tracing his own history in meditation practice—which eventually led him to a series of weeklong retreats and to the intense study of Buddhist doctrine—he makes Buddhist ideas and their history clear. Perhaps he makes the ideas too clear. Buddhist thinkers tend to bridge contradictions with a smile and a paradox and a wave of the hand. “Things exist but they are not real” is a typical dictum from the guru Mu Soeng, in his book on the Heart Sutra. “You don’t have to believe it, but it’s true” is another famous guru’s smiling advice about the reincarnation doctrine. This nimble-footed doubleness may indeed hold profound existential truths; it also provides an all-purpose evasion of analysis.

Still, the Buddhist basics are all here. Sometime around 400 B.C.E.—the arguments over what’s historically authentic and what isn’t make the corresponding arguments in Jesus studies look transparent—a wealthy Indian princeling named Gotama (as the Pali version of his name is rendered) came to realize, after a long and moving spiritual struggle, that people suffer because the things we cherish inevitably change and rot, and desires are inevitably disappointed. But he also realized that, simply by sitting and breathing, people can begin to disengage from the normal run of desires and disappointments, and come to grasp that the self whom the sitter has been serving so frantically, and who is suffering from all these needs, is an illusion. Set free from the self’s anxieties and appetites and constant, petulant demands, the meditator can see and share the actualities of existence with others. The sitter becomes less selfish and more selfless.

Buddhism has had a series of strong recurrent presences in America, and, though Wright doesn’t stop to trace them, they might illuminate some continuities that show why his kind of Buddhism got here, and got “true.” Its first notable appearance was in late-nineteenth-century New England, where, as Van Wyck Brooks showed long ago, Henry Adams was “drawn especially to the lands of Buddha.” Another New England Buddhist of the day was William Sturgis Bigelow, who brought back to Boston some twenty thousand works of Japanese art, and who, when dying in Boston, called for a Catholic priest and asked that he annihilate his soul. (He was disappointed when the priest declined.) These American Buddhists, drawn East in part by a rejection of Gilded Age ostentation, recognized a set of preoccupations like those they knew already—Whitman’s vision of a self that could shift and contain multitudes, or Thoreau’s secular withdrawal from the race of life. (Jon Kabat-Zinn’s hugely successful meditation guide, “Wherever You Go, There You Are,” is dotted with Thoreau epigraphs in place of Asian ones.) The quietist impulse in New England spirituality and the pantheistic impulse in American poetry both seemed met, and made picturesque, by the Buddhist tradition.

The second great explosion of American Buddhism occurred in the nineteen-fifties. Spurred, in large part, by the writings of the émigré Japanese scholar D. T. Suzuki, it was, in the first instance, aesthetic: Suzuki’s work, though rich in tea ceremonies and haiku, makes no mention of Zazen, the hyper-disciplined, often painful, meditation practice that is at the heart of Zen practice. The Buddhist spirit, or the easier American variant of it, blossomed in Beat literature, producing some fine coinages (Kerouac’s “Dharma Bums”). Zen, though apparently an atypically severe sect within Buddhism, came to be the standard-bearer, so much so that “Zen” became an all-purpose modifier in American letters meaning “challengingly counterintuitive”—as in “Zen and the Art of Archery” or the masterly “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance,” where you learn how not to aim your arrow or how to find a spiritual practice in a Harley. It was this second movement that blossomed into a serious practice of sitting lessons and a set of institutions, the most prominent, perhaps, being the San Francisco Zen Center.

Though separated by generations, the deeper grammar of the two Buddhist awakenings was essentially the same. Buddhism in America is simultaneously exotic and familiar—it has lots of Eastern trappings and ceremonies that set it off from the materialism of American life, but it also speaks to an especially American longing for a publicly productive spiritual practice. American Buddhism spins off museum collections and Noh-play translations and vegetarian restaurants and philosophical books and, in the hands of the occasional Buddhist Phil Jackson, the triangle offense in basketball.

The Buddhist promise in the American mind is that you can escape and engage. “Ten minutes a day toward Enlightenment” is the sort of slogan that has inspired the current generation to unimaginably large numbers of part-time meditators. (Among whom I number myself, following guided meditations recorded by Joseph Goldstein, a seventysomething Vipassana teacher who has the calming, grumpy voice of an emeritus professor at City College, though my legs are much too stiff for the lotus position and I have to fake it, making mine in every sense a half-assed practice.) “Don’t just sit there, do something” is the American entreaty. With Buddhism, you can just sit there and do something.

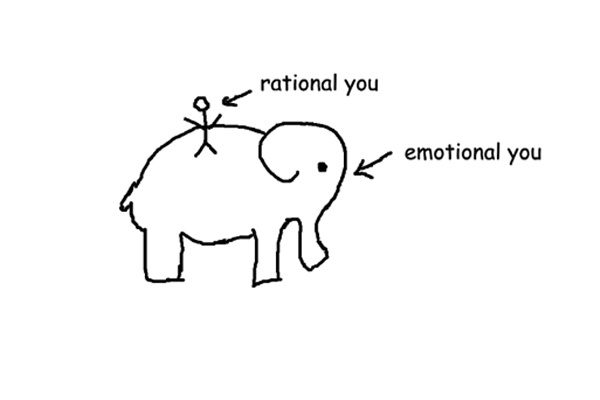

Wright, like his Bay Area and Boston predecessors, is delighted to announce the ways in which Buddhism intersects with our own recent ideas. His new version of an American Buddhism is not only self-consciously secularized but aggressively “scientized.” He believes that Buddhist doctrine and practice anticipate and affirm the “modular” view of the mind favored by much contemporary cognitive science. Instead of there being a single, consistent Cartesian self that monitors the world and makes decisions, we live in a kind of nineties-era Liberia of the mind, populated by warring independent armies implanted by evolution, representing themselves as a unified nation but unable to reconcile their differences, and, as one after another wins a brief battle for the capital, providing only the temporary illusion of control and decision. By accepting that the fixed self is an illusion imprinted by experience and reinforced by appetite, meditation parachutes in a kind of peacekeeping mission that, if it cannot demobilize the armies, lets us see their nature and temporarily disarms their still juvenile soldiers.

O.K. so well have sex and if that works out well go out for a nice dinner and maybe a movie.

“O.K., so we’ll have sex and if that works out we’ll go out for a nice dinner and maybe a movie.”

Buddhism, alone among spiritual practices, has always recognized this post-hoc nature of our “reason,” asking us to realize its transience through meditation. (“Not much really there, is there?” Joe Goldstein murmurs about thought in one of his guided meditations.) Meditation, in Wright’s view, is not a metaphysical route toward a higher plane. It is a cognitive probe for self-exploration that underlines what contemporary psychology already knows to be true about the mind. “According to Buddhist philosophy, both the problems we call therapeutic and the problems we call spiritual are a product of not seeing things clearly,” he writes. “What’s more, in both cases this failure to see things clearly is in part a product of being misled by feelings. And the first step toward seeing through these feelings is seeing them in the first place—becoming aware of how pervasively and subtly feelings influence our thought and behavior.”

Our feelings ceaselessly generate narratives, contes moraux, about the world, and we become their prisoners. We make things good and bad, desirable and not, meaningful and trivial. (We put snappy titles on our tales and then the titles own us.) Wright gives the example of a “buzz-saw symphony” as a small triumph of his emancipation: hearing a buzz saw whining in the background, what would usually have been a painful distraction became, robbed by meditation of any positive or negative cues (this is a pleasant sound / this is an unpleasant one), somehow musical. Meditation shows us how anything can be emptied of the story we tell about it: he tells us about an enlightened man who tastes wine without the contextual tales about vintage, varietal, region. It tastes . . . less emotional. “All the states of equanimity come through the realization that things aren’t what we thought they were,” Wright quotes a guru as saying. What Wright calls “the perception of emptiness” dampens the affect, but it also settles the mind. If it isn’t there, you don’t overreact to it.

VIDEO FROM THE NEW YORKER

How to Draw All The Unread Books Weighing On Your Conscience

Having gone the full Buddha route, Wright gives us accounts of meditation retreats, and interviews with enlightened meditators; he explores sutras and explains dharma. Given that he’s more product-oriented than process-oriented, Wright tends to reflect on the advantages of meditation rather than reproduce their pleasures. Meditation, even the half-assed kind, does remind us of how little time we typically spend in the moment. Simply to sit and breathe for twenty-five minutes, if only to hear cars and buses go by on a city avenue—listening to the world rather than to the frantic non sequiturs of one’s “monkey mind,” fragmented thoughts and querulous moods racing each other around—can intimate the possibility of a quiet grace in the midst of noise. The gong with which Goldstein’s meditations begin on YouTube, though a bit of Orientalia, does settle the mind and calm its restlessness. (Yet many sounds of seeming serenity—birds singing, leaves rustling—are actually the sounds of ceaseless striving. The birds are shrieking for mates; even the trees are reaching insistently toward the sun that sustains them. These are the songs of wanting, the sounds of life.)

Wright has, for the purposes of his book, tied himself to a mechanical view of the constraints that operate on the human mind—the same one that he has posited in previous books, rooted in the doctrines of evolutionary psychology. This is the view—to which Wright is, as a Buddhist might say, overattached—that our deepest desires are instincts implanted by natural selection in our primeval past. Whether or not evolutionary psychology is a real or a pseudoscience—opinions vary—one can believe that human beings are afflicted with too much wanting without thinking that we are that way because once upon a time those cravings helped us have more kids than our neighbors. Even if our desires were implanted by evolution rather than inculcated by culture, they’re still always helplessly double: altruistic impulses encourage us to look after our tribe; genocidal ones encourage us to get rid of the neighboring tribe. Pair bonding is adaptive, but so is adultery: fathers want to care for their offspring and see them thrive; they also want to have sex with the woman in the next cave in order to cover all genetic bets. Desires may arise from natural selection or from cultural tradition or from random walks or from a combination of them all—but Buddhist doctrine would be unaffected by any of these “whys.” If every doctrine of evo-psych turns out to be false—if it’s somehow all culture and inculcation—it wouldn’t affect the Buddhist view about our need to get out of it.

Other recent books on contemporary Buddhism share Wright’s object of reconciling the old metaphysics with contemporary cognitive science but have a less doctrinaire view of the mind that lies outside the illusions of self. Stephen Batchelor’s “After Buddhism” (Yale), in many ways the most intellectually stimulating book on Buddhism of the past few years, offers a philosophical take on the question. “The self may not be an aloof independent ‘ruler’ of body and mind, but neither is it an illusory product of impersonal physical and mental forces,” he writes. As for the mind’s modules, “Gotama is interested in what people can do, not with what they are. The task he proposes entails distinguishing between what is to be accepted as the natural condition of life itself (the unfolding of experience) and what is to be let go of (reactivity). We may have no control over the rush of fear prompted by finding a snake under our bed, but we do have the ability to respond to the situation in a way that is not determined by that fear.” Where Wright insists that the Buddhist doctrine of not-self precludes the possibility of freely chosen agency, Batchelor insists of Buddhism that “as soon as we consider it a task-based ethics . . . such objections vanish. The only thing that matters is whether or not you can perform a task. When an inclination to say something cruel occurs, for example, can you resist acting on that impulse? . . . Whether your decision to hold the barbed remark was the result of free will or not is beside the point.” He calls the obsession with free will a “peculiarly Western concern.” Meditation works as much at the level of conscious intention as it does at the level of unreflective instinct.

Batchelor wants to make Buddhism pragmatic not just in the idiomatic sense—practical for daily use—but in the technical philosophical sense as well: he thinks that the original doctrines of Buddhism were in accord with the ideas of truth put forward by neopragmatists like Richard Rorty, for whom there are no firm foundations for what we know, only temporary truces among willing communities which help us cope with the world. Buddhism, in his view, was long ago betrayed into Brahmanism; the open-ended artisanal practice of meditation became a caste-bound dogma with “truths” and ceremonies. It is a process of fossilization hardly unknown to other spiritual movements—there was a time when Hasidism was all about spontaneity and enthusiasm, and a break from too much repetitive tradition—but in Batchelor’s view it led to a needlessly ornate and authoritarian faith, while his own brand of Buddhism has been restored to its origins.

Batchelor also tackles the issue, basically shelved by Wright, of whether Buddhism without any supernatural scaffolding is still Buddhism. As a scholar, he doesn’t try to deny that the supernaturalist doctrines of karma and reincarnation are as old as the ethical and philosophical ones, and entangled with them. His project is unashamedly to secularize Buddhism. But, since it’s Buddhism that he wants to secularize, he has to be able to show that its traditions are not hopelessly polluted with superstition.

Here Batchelor’s pragmatic turn, made tightly on a sharply curving road, begins to fishtail more than a little. He insists that reincarnation is just an embedded doctrine in the ancient Pali culture—a metaphor like all the others we live with, a cosmological picture that works well, not unlike the metaphors of evolutionary fitness and cosmology that are embedded in our own culture. The centrality of reincarnation doctrines shouldn’t be held as a mark against Buddhist truth.

Maureen Alsop is leaving her magnolia and her delphinium and her cats with us this weekend.

“Maureen Alsop is leaving her magnolia, and her delphinium, and her cats with us this weekend.”