American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us

The Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life held a press luncheon with political science professors David Campbell and John Green on the topic of how religion both divides and unites Americans.

Campbell has written a book with Harvard professor Robert Putnam, entitled American Grace, which examines the changing role of religion in America since the 1960s. In addition to teaching at Notre Dame, Campbell is a research fellow with the Institute for Educational Initiatives and the founding director of the Rooney Center for the Study of American Democracy at the university. He is the author of Why We Vote: How Schools and Communities Shape Our Civic Life and the editor of A Matter of Faith: Religion in the 2004 Presidential Election.

Putnam, who was unable to attend due to bad weather, is a professor of public policy at Harvard University and a visiting professor at the University of Manchester in England. He is a former dean of the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and a past president of the American Political Science Association. He has written more than a dozen books, among them the national bestseller, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.

Green is a senior research adviser at the Forum and the director of the Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics at the University of Akron. He is distinguished for his widely cited surveys, conducted in presidential election years, on the political fault lines running through America’s religious landscape. In addition to his latest book, The Faith Factor: How Religion Influences American Elections, Green has coauthored a number of other books, including The Diminishing Divide: Religion’s Changing Role in American Politics.

Speaker:

David Campbell, University of Notre Dame Professor and Coauthor, American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us

Respondent:

John Green, Senior Research Adviser, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

Moderator:

Alan Cooperman, Associate Director of Research, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

Navigate This Transcript:

Americans Devout, Diverse but Tolerant

Measure of Religiosity by Country

The 1960s: Change in Sexual Mores

Increase in Those With No Religious Affiliation

“Do you say grace?”

Majority Say People of Other Faiths Can Go to Heaven

Religious Fluidity, Interlocking Social Networks

Religion Still a Source of Values and Community

Limits of Goodwill

How Americans Perceive Muslims

Craving a Sense of Community

Intermarriage Blurring the Lines Between Religions

Impact of Education, Income on Religiosity

Democrats, Republicans and Social Justice

Religion-shopping in the United States

ALAN COOPERMAN, PEW FORUM ON RELIGION & PUBLIC LIFE: Good afternoon. Thank you all for braving the snow and the bad weather. Special thanks to Dave Campbell and John Green for making it here today. I’m afraid Bob Putnam is stuck on a runway in New York and, unfortunately, cannot join us.

ALAN COOPERMAN, PEW FORUM ON RELIGION & PUBLIC LIFE: Good afternoon. Thank you all for braving the snow and the bad weather. Special thanks to Dave Campbell and John Green for making it here today. I’m afraid Bob Putnam is stuck on a runway in New York and, unfortunately, cannot join us.

I’m Alan Cooperman, the associate director of research at the Pew Form. I’m sitting in for Luis Lugo, our director, who’s out of town. As you know, the Forum is a project of the Pew Research Center, which is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy organization. We do not take positions on issues or policy debates.

This event is part of our Pew Forum Luncheon Series, which brings together journalists and important public figures to discuss issues of the day at the intersection of religion and politics. Our format for these events is pretty simple. Our guest speakers speak for about 15 minutes each. Today, Dave gets two 15-minute segments; he’s going to speak for Bob, too. So we’re going to give Dave time to give us a presentation. John is going to be the respondent. I want to emphasize that this is on the record for everyone, it will be recorded and we will post a transcript on our website.

At this time I’d like to introduce David Campbell, coauthor of American Grace: How Religion Divides Us. For those of you who don’t have copies, shame on you, but we have some available outside this event in the hallway.

Dave is the John Cardinal O’Hara Associate Professor of Political Science and founding director of the Rooney Center for the Study of American Democracy at the University of Notre Dame. He is an expert on religion and politics and public policy and has published widely on these subjects, including his prior book, Why We Vote: How Schools and Communities Shape Our Civic Life.

The respondent today will be John Green, who is director of the Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics and a distinguished professor of political science at the University of Akron and a senior researcher here at the Forum. John’s expertise and analysis on religion’s role in U.S. elections have been invaluable to our research work over the years.

Dave, take it away.

DAVID CAMPBELL, UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME: The first thing I need to note that I guess is now obvious, but let’s just make it clear: I am not Bob Putnam. However, I do a pretty mean Bob Putnam impression, so throughout the conversation today, I’ll try to slip in a few Bob-isms as often as I can. Thanks.

As was noted in that very kind introduction, I’m going to talk a little bit today about a book that Bob and I have recently published, entitled American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us. I actually found it was interesting that when Alan was introducing me, he mentioned the first part of the subtitle, the dividing part, but not so much the uniting part, which is probably the way most people think of religion in America, actually, that it’s more of a divider than a uniter.

What I’m going to do today is talk about both sides of our story. I’ll talk about some ways that religion does divide American society but then some other ways in which we are united by religion, or at the very least, united in spite of our religious differences. Essentially what I’m going to be doing today is talking about a puzzle — a puzzle that most Americans don’t even recognize as puzzling because it reflects the very world in which they live and probably the only one with which they are familiar.

But by historical and international standards, that is historical comparing the United States against itself in times past but international comparing the United States to other countries today, the U.S. actually does present a very unusual environment for religion in that it simultaneously combines three things. First of all, Americans are religiously devout, and I’ll talk a little bit about that in some detail. We are also a country that is religiously diverse. And yet in spite of those two things, we are also a country that is religiously tolerant. Now, the third of those three is the one that often causes audiences to sit back and say, what? Americans are religiously tolerant?

We’re going to show you some evidence today that that is actually the case, that Americans are quite accepting of those who are of other faiths, which is a remarkable thing given that so many Americans are themselves not only religious in a nominal sense, that is, they have a religious affiliation, but they’re also quite serious about their religion. They attend religious services. They contribute a lot of money to their religious congregations. But in spite of that, we still find a high degree of religious acceptance. So that’s the puzzle. How could America be religiously devout, religiously diverse and religiously tolerant?

But along the way, I’m going to cover a lot of other ground today. Even though I’m going to show you a lot of pictures, I assure you that what I’m giving you is just a small sample of what’s in American Grace. Those who have it in front of them can see that it’s a big book. When we came to Simon & Schuster and said we wanted to write a big book about religion, I don’t know if they understood we meant that literally — a big book about religion. Today I’m going to try to cover at least some of the highlights of what we’ve done.

The research that we report in the book is largely but not entirely based on a survey that we did of roughly 3,000 Americans. We did it in the summer of 2006. We then re-interviewed those same folks in 2007. That actually turns out to be really critical for many parts of our analysis, the fact that we have measures at two different points in time from the same people. That means that you can actually see what stays the same, but it also means you can see what changes. And if things change, that’s where, often, we find some interesting results.

But I should note that even though the backbone of our book is this one survey that we did that we call the Faith Matters Survey, we have kind of pressure-tested the results that we have against lots of other surveys, including those done by folks here at the Pew Forum, but also other national surveys. And we always find that our results converge with those of others.

Let me just also mention, even though I won’t talk about this so much in the talk today, that the book itself is not solely based on statistical analysis, but also has a dozen — what we call — congregational close-ups. That is, we’ve identified religious groups around the country and gone and really soaked and poked within a particular congregation representing that tradition and reported what we found. In the book, these chapters are not really analytical so much as they are reportorial.

The idea is to provide vignettes of how folks of different religious backgrounds live out their faith in the U.S. So this includes Episcopal parishes in Boston, Catholic parishes in Chicago, evangelical megachurches of different types in Southern California, in Minneapolis, a very conservative Lutheran church in Houston, an LDS or Mormon congregation in suburban Salt Lake City, a synagogue in Evanston, a black church in Baltimore and probably others that I have not yet mentioned.

But I mention that because I’m happy to talk in the Q&A about some of the observations we make from these vignettes, but they won’t feature prominently in this particular discussion. But they’re out there. So let me begin the substance of today’s remarks by mentioning something that sets the stage for the puzzle that I’ve identified. And that puzzle is how can Americans be religiously devout, religiously diverse and religiously tolerant?

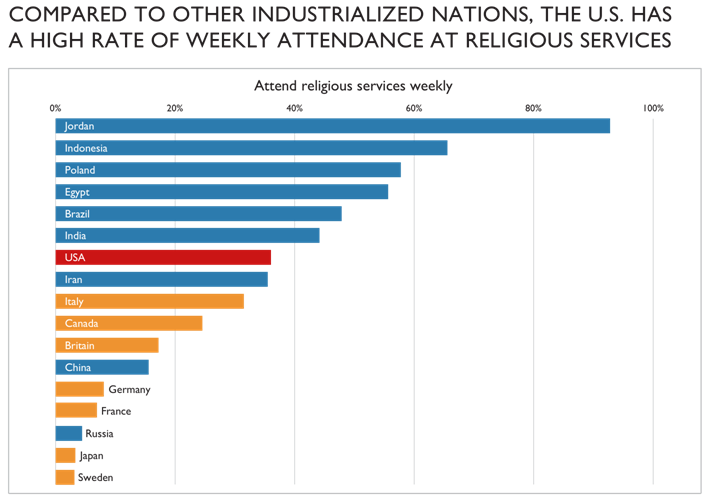

On the devotion part, what this graph shows you very simply is the percentage of people across a bunch of different countries who report attending religious services weekly. The red bar represents the United States. So there’s the U.S. and you can see that down here, we have a variety of countries.

Those in yellow are advanced industrial economies like Canada and Britain, and there are the French and there are the Swedes, whereas the countries above are countries like Jordan, Egypt, Brazil that we don’t think of as being advanced industrial economies. And you can see that the United States, when compared to other industrialized nations, scores very highly on this one measure of religiosity, although this would be true for others as well.

It doesn’t quite rank up there with Indonesia and Jordan, but relative to Italy, Canada, Germany, France, it’s quite high. And this is our favorite little detail: It turns out the United States is actually just a smidgen more religious, at least by this measure, than are the folks who live in Iran. So Americans are actually more religious than the Iranians.

And yet at the same time, as I mentioned, America has a high degree of religious tolerance. Before, however, I get to the religious tolerance part — that is the uniting half of our subtitle — I want to talk a little bit about how religion has divided us as a society. And to do so, I’m going to present a geological history of postwar America because we do see, along societal and political lines, polarization when it comes to religion.

If you go back to the 1950s, you find a high point of Americans’ religiosity. In fact, some historians would argue that it was the most religious period of all of American history. And yet, in a very short period of time, by the time we hit the mid-’60s, America was in the throes of this huge societal transformation, what we refer to as the shock of the ’60s. By 1966, TIME magazine is asking on its cover, famously, “Is God Dead?”

What do we mean by the shock of the ’60s? Well, this was a period of great tumult as sexual mores in the country, in particular, changed. And as those sexual mores changed, religiosity in the United States began to fall. Now, there are lots of different ways that we can represent that shock. But one of the more interesting ones is just simply the fact that when you plot what Americans, themselves, were saying about religion in American society beginning in the 1950s and continuing forward in time, based on Gallup polls, you find that Americans in the 1950s said, yeah, religion has a huge influence in our society.

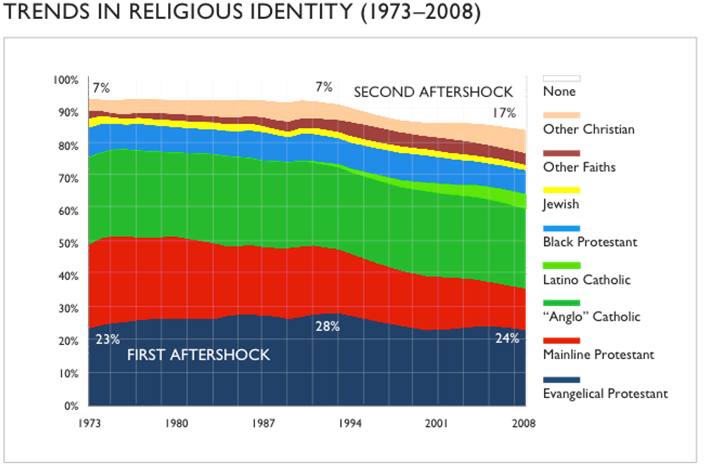

But then by the time you hit the ’60s, that drops off dramatically, and it correlates very tightly with all of these other changes, particularly those related to sexual beliefs and attitudes and customs and practices in the United States. That’s the shock. But it was followed by two aftershocks, both of which are represented in this slide here, which is a rather complex slide, but I’ll just sort of hit the highlights of it.

The first aftershock was in the wake of the 1960s, and it consisted of many Americans who looked out at the changing environment around them and said, you know what, that’s not for us. They looked for a place to worship where they could find moral certainty, and many of them found that place in evangelical churches.

So throughout the 1970s, all the way through the mid-1990s, we see a growth in evangelical Protestantism. That’s what this bottom bar on this parfait-type picture here shows you, a growth in evangelical Protestantism. It wasn’t dramatic, but it was large and the fact that it was growing while other groups were shrinking is itself significant.

Now, that part of our story is, I think, fairly well-known. What is less well-known is that following that first aftershock, there was a second aftershock beginning in the late 1980s, early 1990s. The second aftershock consisted of a dramatically increasing percentage of Americans who report, when asked, that they have no religious affiliation. And so for a long stretch of time, between 5 and 7 percent of the American population would say they had no religion, and then bam, beginning in the late 1980s, early 1990s, we begin to see this rapid increase of people who say they have no religion — the “nones” because they have no religion.

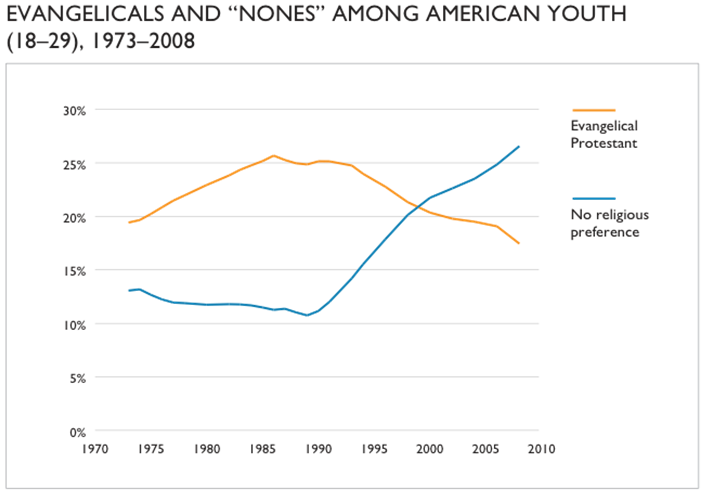

So now they represent roughly 17 percent of the American population overall. But when you look at young people, it’s an even higher percentage, up to a quarter, maybe even a third of all young people today say they have no religion — a much higher percentage than their parents’ generation, than their grandparents’ generation. This slide shows you the idea but contrasts it with what was going on with evangelical Protestants among young people specifically.

These data actually come from college freshmen who were surveyed in hundreds of colleges all around the country. And again, you can see a rapid increase in those who say they have no religion and a decrease in those who are moving to the evangelical side of the spectrum.

Why has that happened? Well, we go into great detail about this in the book. I’ll just mention briefly here that we have good reason to believe that the growth of the nones — that second aftershock — is a direct reaction to the intermingling of religion and politics in the United States. Increasingly what’s happened is that many Americans who are themselves somewhat moderate, maybe on the left side of the political spectrum, when asked today, are you of a particular religion, think, well, wait a second, religion — that equals a particular brand of politics. That’s not my politics, and if I say that I’m of a particular religion, this person’s going to think that I also have those politics and I don’t. Ergo, they report, oh, I don’t have a religion.

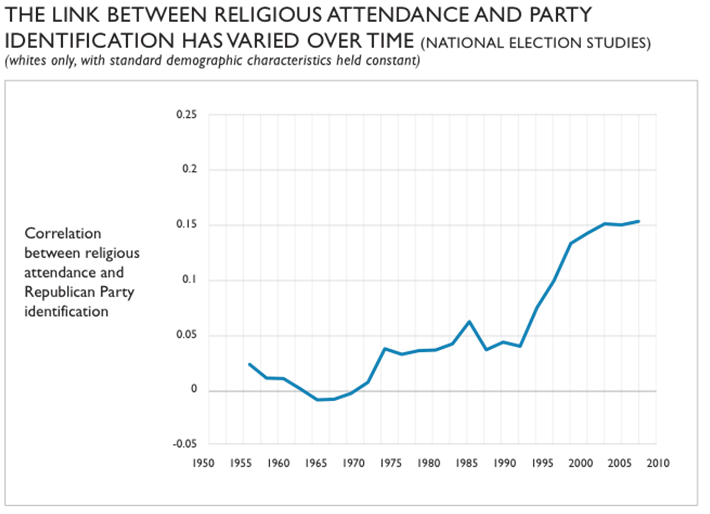

And there’s a lot of evidence that we show that this is actually what’s happening, especially among young people. This slide confirms what we’ve all suspected, which is that beginning in the late 1980s, early 1990s, we began to see a strengthening of the connection between religiosity and conservative, particularly Republican, politics.

The height of this bar shows the strength of that connection — what is, of course, sometimes called the “God gap.” You’ll notice that that happens in the same period that we begin to see the growth of the nones. That’s only one piece of evidence for that. We have much more as well.

So what does that all mean? It means that we have, now, a polarized religious environment in the United States because we’ve seen a growth in conservative religion. That growth has largely stopped and it’s begun to decrease a little bit, but it’s still a sizeable fraction of the American population.

We’re experiencing a growth on the other side of the spectrum, the nones, the folks who say they have no religion, and therefore, a bottoming out in the middle. You don’t find as many people in the moderate religious middle today as we once did. Those changes are tightly connected to changes in the political environment, where, of course, we’ve also seen a lot of polarization.

That’s an awful lot to absorb. We’ve found the following indicator is a useful way to bookmark the sorts of divisions that we find along religious lines in American society, and that is a very simple question we asked in our survey: How often do you say grace or give a blessing to God before you eat a meal?

It turns out that that simple question, how frequently you say grace, divides Americans almost exactly in half. So 44 percent say they say grace daily or more often; 46 percent say well, occasionally or never; and then a small percentage, 10 percent, say they will give a blessing to God before they eat maybe once or twice a week.

There are very few things in survey-type research of this sort that divide Americans as cleanly as this. Carrying a purse would be one of those things, maybe. But saying grace is one of them, and so we found that this is a useful indicator.

The reason why this is so interesting is it’s not just that it splits 50-50. But if I know that you are a grace-sayer on a regular basis, I actually know a lot about you. I can probably predict how you vote. I can probably predict where you land on the political spectrum, and I can predict a lot of things about what you believe and what you might even do in your life. This is a pretty useful indicator of the level of an individual’s own religiosity that we’ve found to be somewhat interesting.

The reason why this is so interesting is it’s not just that it splits 50-50. But if I know that you are a grace-sayer on a regular basis, I actually know a lot about you. I can probably predict how you vote. I can probably predict where you land on the political spectrum, and I can predict a lot of things about what you believe and what you might even do in your life. This is a pretty useful indicator of the level of an individual’s own religiosity that we’ve found to be somewhat interesting.

Up until this point, I’ve given you a little bit of evidence of the first half of our subtitle, that America is divided along religious lines. But as I said at the outset, that’s not our whole story. There’s a second half, a story that doesn’t get told nearly as often, and that’s about the ways that religion unites us, or again, at the very least, that we’re united in spite of our religious differences.

I’m going to present a couple of different factoids to make that point, but I want to emphasize that our argument does not rest on any single one of these. There’s a whole bundle of things that we’ve asked people in these surveys, and other people have asked in their surveys, that all point to the same conclusion, that Americans on the whole are very comfortable with people who are of another religion and in many cases even those who have no religion.

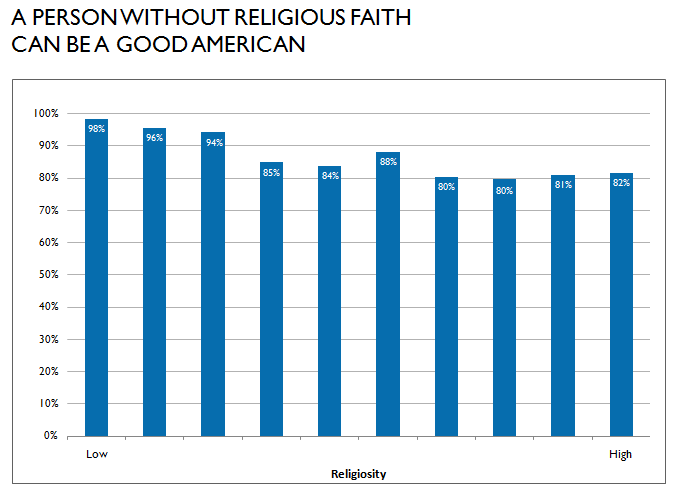

What this graph shows you — the percentage of Americans who are willing to say that a person who does not have religious faith can still be a good American. What we plotted along the bottom is individuals’ level of religiosity. I can go into detail in the Q&A about that, but it’s an index of a bunch of different things that when put together, hang together and therefore suggest to us there’s a pretty good way of differentiating those who are more religious versus less religious.

Then we’ve just sorted them from lowest to highest, and what you find is that no matter where you look on this figure, overwhelming majorities of Americans say, yeah, even those who do not have a religious faith can be a good American. Even the most highly religious Americans say that — 82 percent of them. That’s a pretty remarkable percentage.

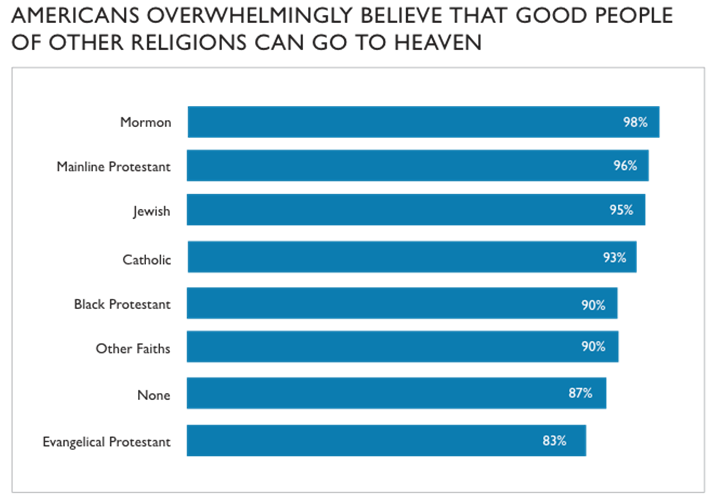

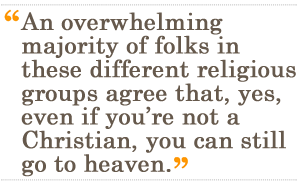

But perhaps what’s even more remarkable is what happens when you ask Americans, do you believe someone who is not of your faith can go to heaven? This slide separates Americans by the religious tradition that they adhere to, and it shows how, say, mainline Protestants or Catholics or evangelicals respond to that question, do you think people who are of another faith can go to heaven?

You can see that across the board, overwhelming percentages say, yes. Ninety-eight percent of Mormons, 93 percent of Catholics, even 83 percent of evangelicals say, yes, people who are of another faith or good people can go to heaven. But some of you are sitting there and saying, well, wait a second, is that just Methodists saying that the Presbyterians can go to heaven and the Episcopalians just saying that the Lutherans can go to heaven — which might be significant, but isn’t quite the same thing as a Southern Baptist saying that a Muslim can go to heaven or a Catholic saying that a Jew can go to heaven.

So on our survey, we didn’t just stop with this one question. We asked a follow-up, which I’ll admit was inspired by a similar question Pew has asked in its research, that says to those who are of Christian faiths, do you still hold that opinion even when those other religions are not Christian?

Again, an overwhelming majority of folks in these different religious groups agree that, yes, even if you’re not a Christian, you can still go to heaven. And that includes a majority — 54 percent — of evangelical Protestants. So there’s some more evidence that Americans are comfortable with those of other faiths.

A key part of our story is also captured in the percentage of Americans who, when asked whether there’s very little truth in any religion, whether one religion is true and others are not, or whether there are basic truths in many religions, overwhelming cluster in that last category. Americans, again, are comfortable saying that there’s truth in other religions. That goes right along with the idea that they value religious diversity and that they’re willing to say that those who are of another faith can go to heaven.

A key part of our story is also captured in the percentage of Americans who, when asked whether there’s very little truth in any religion, whether one religion is true and others are not, or whether there are basic truths in many religions, overwhelming cluster in that last category. Americans, again, are comfortable saying that there’s truth in other religions. That goes right along with the idea that they value religious diversity and that they’re willing to say that those who are of another faith can go to heaven.

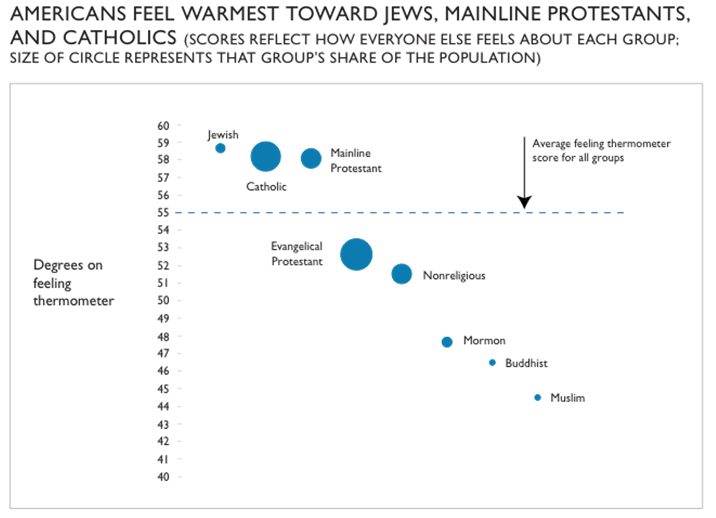

That’s not to say that all groups are viewed the same, and so we have an extended section in American Grace where we talk about how Americans perceive not just some sort of generalized people who are different from them, but actually how they perceive those who are in specific groups. We do so using a thing called a “feeling thermometer.”

It’s kind of hokey, but basically the way it works is if you’re a respondent to this survey, you’re told, we’re going to give you a list of names, in this case a list of groups, and we want you to rate your feeling toward that group, where zero means you’re really cold, 100 means you’re really warm, 50 means you’re neutral.

We asked about a bunch of different religious groups, and what we’ve done here is plotted each of those groups so you can see how they compare to one another. The size of the circle just represents the relative size of that group within the American population. The takeaway finding is that the most popular religious group in America today: Jews, followed closely by Catholics. I promise you that I didn’t just say that because I work at Notre Dame, but Jews, Catholics, followed by mainline Protestants. So those are the three groups that cluster well above the average for all the groups.

Below that, we find evangelical Protestants and Americans who are not religious. We asked it that way because we wanted to capture the way Americans really perceive one another, so we didn’t ask about atheists because the term “atheist” is so loaded. But when you just ask about folks who are not religious, they score a little lower than the evangelical Protestants, but still above 50.

The three groups that scored near the bottom are Mormons, Buddhists and Muslims. These are three groups — undoubtedly, we could think of others, religions that are maybe not as familiar to many Americans, that would also rank on the low end of the scale. But the fact that these groups are near the bottom reminds us that our inclusiveness perhaps still has a ways to go. So while our note in the book is largely optimistic, there is a footnote saying some groups are perhaps not fully included, at least not yet in the full pantheon of Americans’ religions.

However, we are confident or at least optimistic — or at least willing to speculate — that these groups have the potential to move up the chart because even though we don’t have feeling-thermometer data from a generation ago or certainly a hundred years ago, if we did, it’s quite reasonable to expect that these groups, Jews and Catholics, instead of being at the top of the scale would have been at the low end. But instead, we’ve seen over time a progression where these are two groups, once vilified, that are now fully accepted by other Americans.

Now, how can this be? How is it that Americans can combine their devotion, their diversity and their tolerance? The answer, we suggest, is your Aunt Susan. Who is your Aunt Susan? Aunt Susan is that relative of yours — we all have one — who is the sweetest, kindest, nicest person you know. Aunt Susan is the one who brings the casseroles to people when they’re sick. She’s the one you call when you’re in trouble.

But your Aunt Susan, or whoever your Aunt Susan might be — in my case, it’s actually Uncle Harry — your Aunt Susan is of another religion. And your religion, you know, teaches you, theologically, she’s not supposed to be able to go to heaven. But you know that if there’s anybody who’s destined for heaven, it’s Aunt Susan. Heaven was made for Aunt Susan. And when faced with that choice between Aunt Susan and their theology, most Americans choose Aunt Susan.

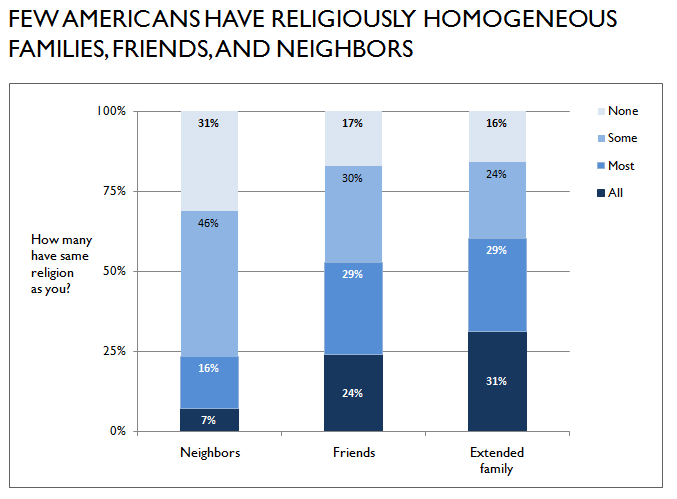

What this graph shows you is the level of religious diversity that we experience on a personal level. Each of these bars shows how many of those folks — neighbors, friends, family — are of a different religion than you.

You can see that in each case, relatively small percentages say, all my friends, all my family, all my neighbors are of the same religion. Instead, they’re saying, my friends, my family, my neighbors are of different religions. We live in a true melting pot.

And lest you think that this is just some kind of fuzzy-headed aspiration — well, yeah, sure, Americans know people of different religions, and, sure, they feel positive toward most other religions, but how do you know those two things really go together? Remember at the very beginning of my presentation today, I mentioned that we interviewed people not just once but twice. That second interview is actually really important because it means that we can trace what happens when things change.

In particular, what happens when you add a friend to your social network who is of another faith? What if you add an evangelical to your friendship network — that is, you become friends with an evangelical or maybe you were already friends with that person and you’ve now come to realize that that person is an evangelical, what happens?

What we find through a lot of statistical analysis that I will not detail here, but I’m happy to talk about in the Q&A if you’d like, what we find, bottom line, is that if you add to your friends someone of another faith, you become warmer toward that faith. Now, that makes sense, right? It’d be I think what most people would expect — become friends with an evangelical, you become warmer toward evangelicals.

What’s not expected but perhaps even more important is that if you add a friend, say, of an evangelical background or someone who is not religious at all to your friendship network, you become warmer not only to people of that group, but to people of other groups as well. Add an evangelical friend and you become warmer toward Mormons or toward people who are not religious.

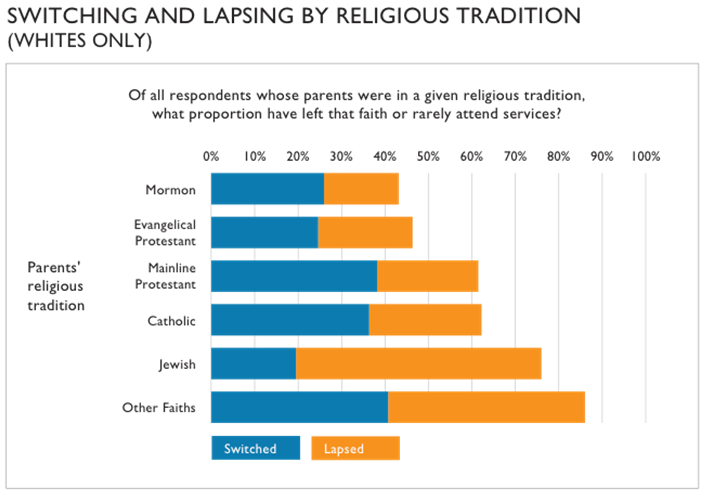

How does that happen? Well, that’s a reflection of the fact that in America, we have a lot of religious fluidity, a lot of switching back and forth between one religion and another. That’s what this slide is showing you, that across these different religious traditions, we have the folks who have switched from one religion to another or they’ve lapsed in their own religion.

Across the board, you see pretty high percentages of people who lapse but also who switch so that roughly a third to 40 percent of all Americans today are in a religion different than the one in which they were raised. That is one way that we get all the religious mixing and mingling that we find in the United States.

So the answer to the puzzle: How is it that America can combine religious devotion, religious diversity and religious tolerance? The answer is this interlocking set of social networks that we have, and that’s what we mean when we refer to America’s grace.

I want to also stress that while our data enable us to see what happens when your friendships change — those can change over a short period of time — we also highlight this amazing trend over time of Americans increasingly marrying across religious lines, such that today half of all marriages performed are across religious lines. It is so common that we often don’t even remark upon it at all.

When Chelsea Clinton was married this summer — our own royal wedding here in America — the fact that she was marrying somebody of another faith — if you remember, her husband is Jewish — barely got any mention at all because it’s unremarkable. But historically, it is remarkable, and it’s yet another way that Americans have managed to build bridges across different religions.

I’ve covered a lot of ground here today, and I don’t mean to suggest that I’ve covered everything. So what I thought I would do is just end — there really is an end, I promise — I thought I’d end on two other quick things that we found that many audiences are quite interested in, that I won’t go into a lot of detail about, but will nonetheless put on the table, if you’d like, to use it as fodder for discussion.

One is, we have a lot of evidence in our book that religious Americans are happier and, for the most part, better citizens and neighbors than their more secular counterparts. And what do we mean by better citizens and neighbors? Well, they’re more likely to volunteer. They’re more likely to give money to charity. They’re more likely to help out in informal ways their neighbors and those around them.

I want to emphasize that that’s not just religious people giving to religious charities or volunteering for religious groups. The secular volunteering and the secular giving of folks who are religious is actually higher than folks who are secular. And so that’s the part of this chapter that gets religious people all excited. Oh, great, there we go; we’re better than everybody.

But it turns out the story’s not quite that simple because the explanation for why we find those high levels of giving and volunteering and just general good citizenship and good neighborliness among religious folks is not what you might expect. It’s not what they believe. We can find no evidence, in tracing 25 different religious beliefs, no evidence that any one of them explains this relationship between religious — religious folks who give a lot.

Instead, it’s their congregation or, more specifically, it’s the friends they have at church. So it’s not just having a lot of friends. Anybody who has a lot of friends is actually more likely to do these good citizenship sort of things. It’s whether or not they have a lot of friends within their religious congregation, which suggests that perhaps what’s going on could be replicated in secular organizations, although the sort of secular group that would replicate what a congregation does is pretty rare. We’ve actually not found many examples of it, but it’s useful fodder for discussion.

Finally, the very last thing I wanted to raise is actually a new point and not something we discuss in the book. But instead, it’s come up in the discussion about our book. And that is the question of whether or not the sort of religious environment we describe in the United States, where everybody sort of gets along or most everybody sort of gets along because we’re building these bridges across religious traditions, does that actually mean the end of prophetic religion in America?

Rod Dreher in The Dallas Morning News wrote the following in an essay about our book: “But it should be remembered that a religion that makes no demands on people other than that they follow their bliss and be nice to everybody else is a religion that has no power to change minds and hearts. It will not inspire people to heroic deeds of self-sacrifice for the greater good, nor is it likely to endure.”

Now, I have to admit, I’m not sure I entirely agree with this statement, but I think it’s a useful point of discussion, something to consider — whether the religious environment that we’re describing in American Grace foretells big changes in the way we see religion and its role in American society.

So with that I’ll end and welcome John’s comments and then your questions after that. Thank you. (Applause.)

JOHN GREEN, PEW FORUM ON RELIGION & PUBLIC LIFE: Thank you very much. It is a little bit humbling to be asked to stand in for Bob Putnam. I kind of understand how pinch hitters who have to go in for Derek Jeter must feel, except I guess in this case you’d have to say that I’m a pinch bowler. Lame attempt at humor, but it is snowing out there. I do have to — in the interest of full disclosure — reveal a certain conflict of interest potentially here. David Campbell’s a very dear friend of mine and a good colleague. We’ve worked together on lots of different things, and I had the privilege of being one of the academic advisers to the Faith Matters Survey that makes up the backbone of American Grace.

So with that in mind, I’d like to make just a few general comments about the book. I don’t want to say a lot because Dave has already presented a lot of really meaty things that I’m sure people will want to discuss in detail. I think this is a very important book, and, Dave, I’m going to do what I promised. I’m going to show everybody the book.

I think it’s a very important book; I think it’s going to change the way we talk about religion and public life in the United States. The book is partly about explicit politics — the politics of public decision-making — things like voting behavior. But it’s also about the implicit politics of a diverse and pluralistic society that expresses itself in public-regarding behavior and civic attitudes and the reverse of that, intolerance, private-regarding behavior and so forth.

The book holds those two things together, I think, in a very creative way but ultimately comes down on an optimistic side. Some critics and people who are basically sympathetic to the argument may wonder if the book isn’t just a little too optimistic. So let me just talk a little bit about that and raise a couple of questions about the conclusions that Putnam and Campbell draw in their book.

One of the interesting things about the book is it really is a nice summary of the research on religion and public life over the last four decades, a lot of which was done here at the Pew Research Center. But then it adds a new level of analysis, a new set of insights, and if I were to summarize what those insights are, it would be the following:

Even in a very modern, secularizing society, religion remains a very powerful source of values, a powerful source of activities and a powerful source of community. Religion may function differently today than it has in the past, but it still continues to function in American society in a very powerful way. But that religion is highly diverse, it’s highly differentiated, and it’s highly dynamic. Those are my version of the D words.

It’s diverse because there are many different kinds of religious people here. It’s differentiated because there are all different kinds of ways to be religious. And one of the interesting things about the book is that those different things are looked at carefully. It’s also very dynamic, as Dave pointed out with his geological description of American affiliation, which changes an awful lot — changes as we speak.

What this important and powerful social phenomenon that is diverse, differentiated and dynamic does is it creates a lot of moving pieces in American society. The argument of this book is in a nutshell that those pieces can come together in highly divisive ways or they can come together in ways that unite our society. A really good example of the divisiveness is the political polarization that Dave talked about. A really good example of unity is the kind of tolerance and civic culture that he also talked about. In this book, both implicitly and explicitly, both of those phenomena occur simultaneously.

The thing that makes it possible for religion to be divisive is also the thing that makes it possible to unite Americans in many other ways. So that’s the sense that we have American grace. Of course, in Christian theology grace is a gift that’s given from God that’s undeserved. And in a sense, Putnam and Campbell are arguing that Americans had no really good reason to be this way, but it turned out that way and it was really quite good — and positive for the most part.

One way to summarize this argument is to quote one of Bob Putnam’s colleagues at Harvard, the political philosopher Nancy Rosenblum, who once said: To talk about faith in America in an empirical way is to investigate faith in America as part of the American experiment. Two senses of faith, right? Faith as an objective but also faith as having optimism and faith in American processes. I’d like to suggest that there are three ways that Bob and Dave could look at their own data that might raise some questions about their optimistic take on this tension that they have in their book.

The first is something that was actually mentioned in the quote that Dave put up on the screen just a moment ago and that is the tension between public-regarding values and private-regarding values. We saw some pretty good examples of that in the 2010 election, the one just past, where there seemed to be a tremendous emphasis on definitions of the private good and a deep skepticism towards government and at least what we have traditionally seen as measures of the public good.

The religion that Campbell and Putnam describe seems to be very good at making people happy, but it doesn’t seem to be particularly good at making for a more just and equitable society. It may very well be that the sociability that surrounds religion has real limitations and what it may really be creating is a private-regarding society rather than a public-regarding society. From that point of view, both people on the progressive side who advocate social justice and people on the more traditional side who advocate morality may be on the outs because both of those approaches to religion in public life demand public justice of one kind or another.

Another thing that I’d like to raise is the limits of the goodwill generated by all this social capital and all this social interaction. It may very well be that this tolerance that comes from the experience of other kinds of people is very fragile. In 2010 we saw what might be a good example of that, which was the sudden controversy that burst all over the country about the Ground Zero mosque. I think in many ways that put this image of tolerance to a test.

Now, it could be that America passed the test. But certainly it was a very, very tough test. It may be that this goodwill that’s generated that Dave and Bob talk about at such length is very fragile and may fall apart when, really, push comes to shove.

Finally, as Dave pointed out, they find very little evidence that this goodwill, this sociability, this tolerance is related to religious beliefs. I believe them. But I wonder if there isn’t more to be said about the impact of religious beliefs. After all, people who are in a congregation are not there by accident. They’re usually there because they believe something or somebody at some time believed something.

So there may be some very powerful indirect effects of religious beliefs on the social capital and the sociability and the tolerance and the civic behavior that the book illustrates so well. A good example of that can also be found in the 2010 election, where in an election that was manifestly about the economy, religious variables — attendance, affiliation and so forth — turned out to be very, very powerful predictors of the vote. Even when we don’t talk about things that connect directly to religion and campaigns, the communities that people belong to can have big political differences, and religious beliefs may be a very important part of that.

I think they have enough to explore for their next book. Thank you very much.

COOPERMAN: I know everybody’s eager to get in, and I’m going to try to get as many people in as possible in the time that we have. But, Dave, briefly, did you want to respond to anything that John said before we open it up to questions?

CAMPBELL: I won’t try to respond to all of this. Thank you very much, John, for your useful comments and directions for where we might go next.

I think the one point worth discussing, and I don’t have necessarily a neat and tidy answer to it but it’s certainly one that we’ve thought a lot about, is what our book actually tells us about how Americans perceive Muslims. You’ve alluded to that with your reference to the controversy over the mosque, or the Islamic center, in New York City close to Ground Zero.

Our book actually came out right in the midst of all of that so we got a lot of questions about whether this American grace we’re describing was something of the past because today it looks like this is a group that’s not perceived very positively by the American population. And that’s true. But it’s also true that not very many Americans know a Muslim. And the reason we asked not only about Muslims — remember the slide where we were showing how people respond to different religious groups — but we also asked about Buddhists.

The reason we chose Buddhists was we wanted to pick a religion that we thought would be somewhat unfamiliar to most Americans but was innocuous. I mean, maybe there’s a really strong anti-Richard Gere sentiment or something in the United States. But it’s hard to imagine what somebody would have against Buddhists, whereas hostility toward Muslims — there’s a story that goes along with that.

Yet you find that Buddhists and Muslims rank pretty closely to one another, with Mormons in there as well. And what do those three groups share? These are groups that are relatively unknown to most Americans, especially on a personal level. So — this is what I was saying —we are willing to speculate that should it be the case that the Muslim population in the United States grows and connects with the rest of society — should that happen, we would expect to see America’s grace extended more fully toward that group or any group.

Now, whether that will happen, it’s tough to say. A prediction is hard, especially about the future. But that’s what the past suggests we’re in for going forward.

COOPERMAN: That’s terrific for teeing up the fact that the Pew Forum will be coming out with a report next month on the growth of the Muslim population in the United States and around the world. But we’ll leave that — that’s next month.

OK, great. Let’s get started.

JEROME SOCOLOVSKY, VOICE OF AMERICA: Your findings are making me wonder why Americans are so religious — or like a chicken-or-the-egg question — is it that we crave a sense of community that maybe in other countries people get elsewhere, and as a result, we have these beliefs? Or do we have these strong beliefs, and as a result, we’re in these communities that make us happy and good citizens?

CAMPBELL: That’s a good question. I would lean more toward the latter in that it’s not so much that Americans don’t have other opportunities to form communities. I actually think that even though a certain someone has written a book claiming that America’s in a state of civic decline — OK, my coauthor — that’s true, America relative to itself. But America relative to the rest of the world, we’re actually still quite a joining society, whether you look at religious groups or secular groups.

What I think is a more likely explanation for the high level of religiosity among Americans stems back to the constitutional architecture of the country, given that we have never had a state church, per se. Instead we’ve always had a very innovative, even entrepreneurial, religious environment in the country. I’m somewhat persuaded that that has been a major factor in explaining why so many Americans continue to connect with a religion when in other countries that has not necessarily been the case.

This is also why — and I want to emphasize this — even though in American Grace we’re describing this upward trend of folks who say they have no religious affiliation, if you probe a little further, it’s not that these folks are atheists — not by any stretch of the imagination — nor even that they’ve abandoned sort of core religious beliefs. Most of them believe in God and they believe in a heaven. They just don’t like organized religion, or at least organized religion as they see it in front of them today.

Given how entrepreneurial American religion is, it’s pretty likely that someone will figure out how to bring many of those folks back to the pews. They’re sort of yearning, we think, for a form of religion. And so I wouldn’t assume that America’s on its way toward European-style secularism simply because of the way American religion has operated in the past.

ANDREA STONE, AOL NEWS: I have a news-related question. Last night — I don’t know if you saw — but in the Senate there was a back-and-forth between a couple of Republican senators — Sens. Kyl and DeMint — and Sen. Reid. Sen. Reid wants to keep the Senate in maybe through Christmas and maybe after the holiday, and the Republican senators accused him of being disrespectful to Christians. One of them said this is one of the two most important holidays for Christians. And Harry Reid got on the floor and was vehement about them being sanctimonious and — nobody has to lecture me as a Christian.

I’m wondering if you could put that into some context in what you have here in this book. Does that surprise you, or what does that say about us that this would come up?

CAMPBELL: I have to admit I’ve not actually heard this story so if I could ask a follow-up: You said that Harry Reid made a point of noting that he is a Christian and he sees himself —

STONE: I believe the quote was, “As a Christian, I don’t need to be lectured to,” or something to that effect.

CAMPBELL: And has he received any blowback from that?

STONE: They’re still going tit-for-tat over this, and then other people have talked about, well, plenty of people work on Christmas, and the soldiers in Afghanistan don’t get to come home, and working people have worked on Christmas and all. So that’s sort of the context.

CAMPBELL: Let me address where that, I think, fits into our larger political context. The reason that I asked the follow-up about Harry Reid is — this is probably known to everybody in the room — Harry Reid is himself a Mormon, and Mormons are often accused of not being Christians. And so I was wondering whether somebody had picked up on, what’s Harry Reid going to tell us about Christianity?

I think what you’re describing is a nice example actually of the way our two parties have dealt with religion over the last generation or so. I showed you the one slide that represents what is often called the God gap, the connection between religiosity and supporting the Republican Party. That manifests itself in lots of different ways. One of the more interesting ways is if you ask Americans which party is friendlier toward religion, they’re much more likely to say the Republicans than the Democrats.

And if you look at what Republican candidates say, even in obscure House races that don’t get much national attention, there are very frequently references to God, and they’re usually linked to what we call the “sex and family” issues of abortion and homosexuality. The Republican Party has now spent a generation building up its brand along those lines in a way that we did not see, say, back in the 1970s or certainly not back in the 1950s, where there was no God gap. Being religious didn’t tell us anything about your politics.

So I think that’s probably what the Republican senators you’re referring to are feeding into. Maybe they’re even doing it subconsciously — this is just what we do because we’re Republicans; we’re the party that talks about God.

MARK PATTISON, CATHOLIC NEWS SERVICE: I wanted to ask you some questions regarding intermarriage. I don’t know how deeply you were able to delve into this versus what you were able to get into, even in a book of this size. Is intermarriage a distinctly American phenomenon compared to other industrialized nations or even other Western nations? And at least from my own lived experience, it seems to be more often than not the husband who joins the religion of his wife.

And are we creating a society in which we have nominal Methodists because they’re kind of like Baptists in a Methodist church or Methodists worshipping in a Catholic church? There seems to be some kind of flattening out of religious truths, and the distinctions between one faith and another don’t seem to be so great for them to be able to make a switch to another religious denomination.

CAMPBELL: Thank you. That’s a very good question. We don’t have good data on interreligious marriage in, say, most Western European countries, which itself is telling. It’s not a question that people would think to ask. That suggests actually that there’s a high level of religious intermarriage in other countries.

The difference between those sorts of countries and the United States is that for many of those people — most of them, actually — their religion doesn’t matter all that much, whereas in the U.S. we find religion does matter in the sense that people report religious affiliation, they opt to attend services, they contribute their time and talents to a congregation. And yet they’re still marrying across religious lines.

I can say — and this is really quite startling — that the data we have that shows the rate of religious intermarriage over time in the United States goes back to the 1910s. If you look at that data and the percentage of Americans who married across specifically Catholic versus Protestant lines, America a hundred years ago looks like Northern Ireland today. We’ve actually done a version of our Faith Matters Survey in Northern Ireland, as well as in the Republic of Ireland and the U.K., and that’s just one finding that’s really striking to us, that there you have a religiously segregated society today that looks like what America looked like a hundred years ago.

You also asked about whether the religious intermarriage you find within couples suggests that there’s a blurring of the lines between religious traditions, and I think that that is certainly the case. It’s almost true, I think, by definition if you’re able to make an interfaith relationship work and you come up with compromises where you raise kids in sort of an amalgam of the two religions.

I think this actually gets to the point that Rod Dreher is pointing out here, that if we have a society where people are marrying across religious lines and forming other relationships across religious lines and therefore coming to the conclusion that, well, maybe my religion isn’t all that distinctive after all, what does that say about the future of American religion? I think that is an open question and we’ll just have to wait and see what happens. But certainly there’s a good reason for us to want to watch to see because it could have a huge impact on our society.

DOYLE MCMANUS, LOS ANGELES TIMES: I want to ask about two demographic factors that you didn’t mention: income and education. As I’m sure you know, there’s some data and some studies out there that suggest that the drop-off in church attendance and religion affiliation is steeper among lower-income and lower-education groups than higher-education groups — the degree that church attendance may be more now a higher-education, higher-income activity than a lower-income —

CAMPBELL: Which, by the way, is 100 percent consistent with our evidence as well, so — yes, we’re onboard there.

MCMANUS: I wanted to ask what happens when you apply those screens to the phenomena you’re talking about, but also when you look at the question of what makes religious people happier and more engaged citizens. How do you disentangle that from income and education and family stability and security, all of which are in the Bowling Alone basket of factors that make it easier and more habitual for people to be engaged?

CAMPBELL: The quick and dirty answer to how we account for income and education and these various things when we’re trying to tease out the effect of religiosity on anything — on happiness, on civic engagement, on whatever indicator you’re interested in — is that we control for it statistically. That may not be a very satisfactory answer, but what that really means is that we are in a sense holding all of that steady. I don’t want to overstate the class differences in religiosity in the U.S., but there are some differences and we’re able to account for that.

But probably what’s more important to note is that the trends that we describe are actually themselves — intermarriage and such — not concentrated within a particular segment of the U.S. population. So it’s not just high-educated or low-educated people. It’s not just the rich or the poor who are marrying across religious lines, for example, or who are friends with people of another faith. That’s not what seems to drive it. It’s other factors, more than that.

Was that responsive to you?

So I guess the bottom line is, there are some important things to be said about class and religion in the United States, but most of what we’re describing is sort of the same across class lines.

MCMANUS: Let me just back up, though, to take the first point. Is religion and religious activity becoming an upper-income, higher-status pursuit, trait, marker to a degree that wasn’t the case 20 years ago?

CAMPBELL: Yeah, I don’t know if I want to say that we’re at a point where there’s a sharp divide between those who are highly educated and less-educated in terms of their church attendance. The trend is such that those who are dropping out of church or less likely to attend church are more likely to be on the lower end of the spectrum. But there’s still an awful lot of people on that low end of the spectrum who are frequent church-attenders.

The reason why I’m equivocating a little bit is that how class and specifically education relates to religion really depends on the particular measure of religion that you’re using. So middle-class and upper-middle-class people are more likely to attend church, but they’re less likely to hold what we might think of as orthodox or traditionalist religious beliefs. So those two things are sort of cutting against each other.

I should note actually that where you find a really striking class difference on religiosity is within the African-American population; middle-class and upper-middle-class African-Americans are far more likely to attend religious services than blacks at the lower end of the scale, which is remarkable because that’s a population that is arguably the most religious overall in the U.S. But it’s also where you find the sharpest class divide.

ELIZABETH TENETY, THE WASHINGTON POST: I am really interested in this quote from Rod Dreher, in particular what — now I’m writing down the tolerance trajectory and what’s happening as we are pluralistic. Were you able to measure doubt in any way that’s related to being pluralistic? So if you have a Muslim friend and you thought you lived in this Catholic universe, and then you think, okay, your pal Sal, she’s not so bad, does that have a direct relationship on all of these orthodox beliefs? And where do we see that going? Do you have any sort of measurable information?

CAMPBELL: Well, here and now — that is, the data that we’ve currently collected — we do not see any diminishment in the fervency of people’s religious beliefs if they have religious networks that are diverse, which is remarkable. But that doesn’t mean that that would necessarily stay the same over time. So going forward, we might very well see a diminishment in the staunchness, if you want to put it that way, of people’s religious beliefs as we become a more pluralistic and interconnected society.

But we haven’t see that thus far, which suggests that maybe Americans have figured out a way to hold to their religious beliefs but also be accepting of those who are of another — (inaudible, audio break).

TENETY: A follow-up is, are the nuns in any way likely to have more friends of varying traditions? Are they in any way socially diverse? I’m particularly interested in this younger generation.

CAMPBELL: That’s a good question. And yes, to some extent they are, although again, the differences are not dramatic. But yeah, they’re a little more likely. And not surprisingly, young people themselves are more likely to have friends who are not religious because that’s the group where you find the nuns concentrated.

ANTHONY POGORELC, CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY: I just wanted to make a point on orthodox beliefs. Oftentimes it’s assumed, for example, that an orthodox belief is that only Christians would go to heaven or that a true believer is a biblical literalist. Neither of those are Catholic orthodox beliefs. Catholics believe in universal salvation since the Vatican Council, and we’re not biblical literalists. I think it’s important to realize that there are variations among what constitute orthodox beliefs.

CAMPBELL: Thank you for that comment. Hopefully in the book we’re able to spend more time on this. We do justice to points like that, I think particularly the point about biblical literalism is important because often we focus on questions like that that are really more appropriate for a Protestant than a Catholic audience.

On the question though of who goes to heaven, it’s interesting that that’s a belief that is held among Catholics but also Protestants as well, even though Protestantism, particularly of the evangelical flavor, should hold to the belief that there’s a particular set of things you need to do and believe in order to go to heaven. That does for the most part seem to be what they hold to.

Again, it’s the Aunt Susan principle.

JENNIFER SKALKA, WASHINGTONIAN: I’m interested in the flurry of conversion activities that you discussed. If you could provide a general overview about what you’re seeing generationally and then also regionally. And beyond interfaith marriage, what are some of the other reasons that people are converting today?

CAMPBELL: On converting, that is moving from one faith to another? We have a chapter in the book where we are able to look at why people switch from one religion to another and also from one congregation to another. And those are not always the same thing. You might remain a Methodist but choose to attend this Methodist church rather than that Methodist church. Not surprisingly, you find first of all regional variation in overall religiosity. So some parts of the country — the South and Utah are the two sections of the country where people are most likely to be religious by any measure.

In terms of where you find the most religious switching, you are actually more likely to find that in the more secular parts of the country. Part of the reason for that is simply that the religions that are least likely to quote, unquote, “lose their members” are also those religions that are concentrated in the South and in Utah. So evangelicals and Mormons are a little more likely to hold onto their flock than other groups.

The younger people are across the board more likely to switch and be open to other religions. It’s a little hard to say when we’re talking about the millennials because so many other things about their lives have been postponed. So we know that people generally become more religious as they get older. That usually is accompanied by being married or buying a house or having children. That, for the most part, hasn’t yet happened with the millennials. So we don’t know exactly what will happen. Where are they going to settle down? No church? Will they find a church? Will it be different than the one they were raised in? That’s kind of open but I would suspect, based on what we do know about that population, that they would be more likely to just settle down in a new faith or some sort of amalgam.

Robert Wuthnow at Princeton, who’s a sociologist of religion, refers to today’s young people as “tinkerers” in their religious beliefs and practices. I think that’s a very good way to put it. They often “tinker” and are able to combine things that their parents, certainly their grandparents, would not have been comfortable doing.

WILLIAM D’ANTONIO, CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY: I want to return, David, to the response that you made on the brouhaha in the Senate between Reid and Kyl. You commented about the fact that the public generally would consider the Republicans more friendly to religion than the Democrats. That’s a truism that fits the sociological principle, if things are perceived to be real, they become real in their consequences.

What is measured in religiosity is nicely given in your chapter where you interviewed the minister in the Midwest, and he talks about the fact that he won’t tell his people how they should vote ,but he says, there are things that are important to us. One is traditional family; the other is the sacredness of life. So now he’s rattling off what is sacred to the Republican Party: anti-abortion, anti-same-sex marriage, homosexuality, the whole business.

I’ve been studying roll call votes in the House and Senate over the last 40 years, and one thing that strikes me is the fact that up until about the mid-1970s, Republicans and Democrats looked a lot alike on social justice issues. You got a lot of Republicans who supported those.

Since then, you look at the votes and the Democrats, up to 90 percent, have supported what to me as a Catholic reflects the social teachings of the Catholic Church. To my mainline Protestant friends who are believers in the social gospel, it reflects their belief. And if you’re a Jew and if you read the rabbi in your book, he rattles off the necessity that Jews have to respond to the needs of the public.

That has never been called part of being religious by the press. That’s just the idiosyncrasies. I would argue that the Democratic Party — and I’m going to try to show it in this forthcoming book — is rooted in the Bible. It’s Abraham who is told by God not to turn his face on the aliens. And Jesus never quite said, be sure to get to the synagogue every Saturday. He said, feed the hungry, clothe the naked, find shelter for the homeless. He said it in a thousand different ways.

I would simply argue here that some of you who always write about who’s religious ought to rethink the notion of religiosity because I’m trying to redefine it. When I asked the millennials in our 2005 survey what identified them most closely as a Catholic, 91 percent, the first thing they said ahead of Jesus being important to them was concern for the —

CAMPBELL: Really? Ninety-one percent?

D’ANTONIO: — poor in their society. Ninety-one percent. If you’d read our book, you would have seen it. (Laughter.) So I’m concerned about that notion of religiosity, at least in this kind of discord, and why we have this polarization in Congress.

CAMPBELL: Thank you for that obviously very informed comment. I guess I would respond by saying I don’t have any quibble actually with how people want to characterize one party versus the other. But it is striking that the issues on which you find the biggest differences between religious and secular Americans are, again, the sex and family issues of abortion and gay marriage. So care for the poor or the sort of thing you’re describing is popular among both religious and secular Americans, whereas a traditionalist position on marriage or a pro-life position on abortion is largely concentrated among those who are more religious, and that’s really all we mean by saying that religiosity is reflected in one party versus the other.

I agree that that’s all a matter of perception. It’s just a matter of what’s inside people’s heads when you ask essentially about brand labels. I mean, it’s like asking what do you think of when we say the word “Coca-Cola” or “Pepsi cola”? It’s the same sort of thing; it’s what’s at the top of their heads, and for many Americans, Republican equals religion.

D’ANTONIO: That may be why we see no Jewish Republicans in the Senate and only one in the House. And the one in the House, of course, become quite famous now.

STEPHANIE SAMUEL, THE CHRISTIAN POST: I just wanted to add also that there has been talk among some evangelicals, notably Chuck Colson, during the election about kind of dividing themselves or pulling away from the Republican Party and embracing more of that social justice concept within the Bible and within the life of Jesus Christ. I wanted to know if the God gap could be healed by simply just moving away from partisan politics.

CAMPBELL: That’s a good question. I would answer yes or probably yes. Again, just looking at the past. We don’t have to go way back in the past. You just have to go to the mid-1970s to see a time when Americans really didn’t divide along religious lines when it came to their politics.

How we would get from the current situation to a situation like that again is harder to see for precisely the reasons that were highlighted by this recent story coming out of the Senate that the two parties have fallen into a way that they talk about religion. Maybe a better way to put it is that the Republicans have a way they talk about religion and a way they exploit religiously oriented issues that if that continues, it’s hard to see how the God gap would close.

But if that were to end, well, then all bets are off, and it would be probably a matter of new political entrepreneurs finding ways to build new religious coalitions. I suspect that the time will come when that will be the case, but it’s not going to happen in the short term.

SAMUEL: If I could just follow up with that? I think someone spoke about tolerance being fragile, and also I heard a remark that there is this kind of need or desire for people to come from the pulpits to bring people back into the pews. I think it was the second aftershock you were talking about.

So what are some of the things that really could be stressors to tolerance, especially now that we’re moving into a new era in the House? More Republicans coming in — you’re already hearing things about abortion and gay rights policies. So what are some stressors and what are some things that could probably lessen that God gap and really pull people back into the pews?

CAMPBELL: Let me just address one of the points that we actually make in the book about the potential future for the God gap and that is that on the two issues that most divide religious and secular Americans, you find among young Americans opposing trends. So on gay marriage or just homosexuality in general, it’ll come as no surprise, I’m sure, to folks in this room that young people are increasingly accepting of gays and therefore of gay marriage.

But the trend is going — rather than in a liberal direction — in a conservative direction on abortion so that young people today are actually more likely to be pro-life or at least ambivalent about abortion than are their parents’ generation. So the fact that those two issues are moving apart from one another among younger Americans suggests that there will be an opening for political entrepreneurs to come in and construct a new coalition.

The reason why that pro-life finding about young people is so interesting is that they are also the most secular group of the population. So much of what is driving their attitudes about abortion is not necessarily coming from their religion, per se, although undoubtedly, it’s being informed by arguments made by folks who are religious and pro-life. That maybe says something about what we might be seeing in the future.

I alluded to this in the presentation, but I can talk about it here in slightly more depth. The type of entrepreneurial response on the religious side to the growth of the nones that we would expect would probably be a religion that has an evangelical flavor to it but was devoid of the politics, and specifically devoid of the emphasis on homosexuality, that that seems to be the one issue that young people just pull away from and don’t necessarily want to hear religious leaders emphasize.

In the book we mention a movement that undoubtedly is familiar to some in the room — the emerging church — which some believe may be an example of the type of religion that is reaching out to young people. It has an evangelical flavor, and it’s hip and urbane and all of that, but at the same time doesn’t have the politics in its message. Whether that’ll turn out to be successful over the long haul is tough to say. It’s really difficult to predict what’s going to happen except we are pretty confident that there are going to be a lot of attempts to do it. And given history, it’s likely that somebody’s going to figure it out.

TERRY MATTINGLY, SCRIPPS HOWARD NEWS SERVICE: I was interested in knowing how your book defines tolerance. I’m reacting primarily to a great book written years ago by Stephen Bates called Battleground about public education issues in America. He says America is caught between two conflicting definitions, one historic and one rather new, of civic toleration, which is all faiths are equal in the eyes of the state, and another form of toleration, which is all faiths are equal in the eyes of God. I was wondering how your book defined it and dealt with that tension.

CAMPBELL: It’s a good question. I have to admit I’m always a little hesitant to use the word “tolerance” because it can mean so many different things to so many different people. What we’re describing as religious tolerance might also be described as religious acceptance.

I say that because sometimes when people talk about tolerance, what they specifically mean is how you view the free speech rights of an unpopular group, and that’s not necessarily what we’re getting at here. It’s, as I said, whether or not you believe that people of other faiths are going to go to heaven and whether you believe that they have a place in the American picture.

So I would imagine that when we ask people, do you believe that someone who is not of your faith can go to heaven, and they say, yes, that that would fall under the rubric of what you were describing, whether or not people of different religions are viewed as equal in the eyes of God and not just in the eyes of the state.

MATTINGLY: Then let me ask the logical follow-up. Did your question say “can go to heaven” or “will go to heaven”? Because after Billy Graham emerged on the scene in the ’50s, even evangelical Protestants would say only God would know. You’ve got two very important words. Did you say “can” or “will”?

CAMPBELL: That’s, again, a very good question. The specific wording actually does say “can” rather than “will,” although I will also point out again that our argument about religious tolerance does not hang on that one question because I know this isn’t the first time I’ve had people ask about it and it’s a reasonable thing to ask.

It’s also true that other surveys, whether done by Pew or others, that ask similar things with different wording all got kind of the same story, which tells us that it doesn’t hang on whether it’s can or will, but rather it’s capturing a general sentiment among the American population. But I can understand why there is some nuance there that maybe we’re not fully capturing.

ERIC MARRAPODI, CNN: I wanted to ask you specifically about the statistical compilation of your study. It struck me that the gap between when you first asked and second asked was relatively short, statistically speaking. Was a year enough time statistically for people to really have any significant change in their beliefs and opinions on this?

CAMPBELL: Very good question. Let me begin by saying the book reports on a second set of interviews. We’re actually now going to do a third — we’ve gotten funding for that and that will be a five-year span of time, which is by the standards that people do this sort of research almost an eternity.

Your question about whether a year is enough time to capture differences — in our case, what I was emphasizing here, people’s religious social networks, was one that we actually had. It was an empirical question. Could we actually see any change? I don’t want to overstate it. It’s not like people go through a dramatic change over a period of a year and all of their friends turn over.

But we did find enough variation that we are able to see what happens when you have fairly minor changes but the minor changes lead to noticeable results, which suggests that over a longer period of time, where there would be bigger changes in people’s lives, we’d find changes that were yet bigger still.

So I guess my answer is you’re right to be skeptical that we would find anything over such a short period of time. We, too, were skeptical. But when we looked, we actually do see some results, and the fact that we had every reason to think that we wouldn’t — well, when you do find it, that is probably reason to underscore that there’s something there.

MARRAPODI: Just one quick follow-up question on that. In the day-to-day, when we’re out on the street doing reporting on religious issues, the one that comes up the most is the deer in the headlights on a self-identification question. It’s encouraging to hear that you have found statistically some of the same things that we encounter every day.

CAMPBELL: By which you mean, when you ask people, what religion are you, they just stare blankly and they don’t know what to say?

MARRAPODI: Yeah, and typically what I find or have found in the past is if they tend to be a liberal evangelical or a mainline, they will hem and haw if you ask them if they are even a Christian. So I’m wondering how you accounted for those folks. I was curious if many of them didn’t just fall into the none category because they are terrified of self-identifying and being labeled a jerk because of the way that Christians have behaved. You talked about specifically glomming on politically and — just because I’m a Christian doesn’t mean I’m a Republican. How did you account for that?

CAMPBELL: We account for it by first, if somebody says they have no religion, they go into that category, and then we know lots of other things about them and they fit the profile that you’re describing. Actually what you’re describing is remarkable, given what we see in our data. We should do a film version of American Grace, and the clips that you’re describing would illustrate this perfectly.

Another interesting point about the folks who are nones, and I think this speaks directly to what you’re finding when you interview folks, is that when you go back to those same people a year later and ask what religion are you, it turns out that roughly a third of those folks who initially said they have no religion — a third of them — when we ask a second time say, well, yeah, I have a religion. I’m Methodist or Lutheran or whatever.

That’s a pretty high rate of inconsistency. We call those folks the liminals. They’re like Spock, who’s half-human, half-Vulcan. (Laughter.) They’re half in; they’re half out. Ask them on a Tuesday, no, I’m not anything. Ask them on Wednesday, well, mom was a Lutheran; dad wasn’t anything. I guess that makes me a Lutheran, right?

In other words, religion doesn’t matter much to them, and we can see, again, over that year period for most of those folks there’s been no other change in their life. There’s no reason to think they’ve gone through any kind of conversion experience. They’re just on the line. They don’t know whether they are in or out.