Resources from this Teacher

- Emilie Cady

- Lessons in Truth Chart (Unity Minister's Assoc)

- Lessons in Truth Chart

- Lessons in Truth (Audio)

- Lessons in Truth (Text)

- Emilie Cady — Lessons In Truth (Study Edition)

- Emilie Cady — How I Used Truth (Text)

- God A Present Help (1938 Unity Edition)

- The Will of God

- Trusting and Resting and In His Name

- Finding the Christ in Ourselves

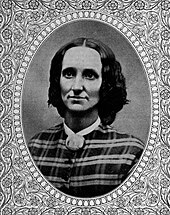

Emilie Cady

June 19, 2020. Willow Creek Cemetery, Dryden New York

About Emilie Cady

We have an wonderful 2-part biographical overview of Emilie Cady from Russell Kemp, published in Unity magazine in 1975. Click here for Part 1 and click her for Part II.

From Wikipedia:

Harriet Emilie Cady (1848–1941) was an American homeopathic physician and author of New Thought spiritual writings. Her 1896 book Lessons in Truth, A Course of Twelve Lessons in Practical Christianity is now considered the core text on Unity Church teachings. It is the most widely read book in that movement, and has sold over 1.6 million copies since its first publication.

Born in 1848 in Dryden, New York to Oliver and Cornelia Cady, Cady's first job was as a schoolteacher in a one-room schoolhouse in her hometown. In the late 1860s, however, she decided to pursue the field of medicine, and enrolled in the Homeopathic College of New York City, graduating in 1871, and becoming one of the first woman physicians in America.

Introduced to the teachings of Albert Benjamin Simpson, Cady became deeply involved in spiritual and metaphysical studies. She was inspired and influenced by Biblical teachings and the philosophy of Ralph Waldo Emerson. She was taught by Emma Hopkins, the New Thought "teacher of teachers".

Cady also associated with several prominent figures in the New Thought movement of the time, including: Emma Curtis Hopkins, Divine Science minister Emmet Fox, Ernest Holmes, founder of Religious Science, and Charles and Myrtle Fillmore, co-founders of Unity Church. Finding The Christ in Ourselves, a pamphlet she had written and sent unsolicited to Charles and Myrtle Fillmore, was published by them in the October 1891 issue of Thought.

Cady died January 3, 1941 in New York City.

From Metaphysics to Mysticism

Talk given November 15, 2021 at Unity of Hagerstown, Maryland