Toshihiko Izutsu:

The Genius That Bridged East & West

May 28, 2021

Toshihiko Izutsu, best known as the translator of the Quran—arguably the most famous translation of the sacred text from Arabic into Japanese—studied at Keio University, where he went on to become a member of the academic faculty. A linguistic prodigy and master of more than 30 languages, Izutsu made a lasting impact on scholarship through research that spanned Islamic studies, Eastern thought, and mysticism. Here, we follow the footsteps of this intellectual giant, who wielded an enormous wealth of knowledge on language and issues across many academic disciplines.

A commemorative photo taken on November 9, 1949, at the award ceremony of the first annual Fukuzawa Award and Keio Award, a tradition that continues today. Izutsu (seated at far right in the front row) won the Fukuzawa Award for his book Mystical Philosophy: The Greek Edition. (Photo courtesy of the Fukuzawa Research Center)

Encounter with Professor Junzaburo Nishiwaki Sets Izutsu on a Course Destined for Academia

Toshihiko Izutsu was born in 1914 in the Tokyo neighborhood of Yotsuya—modern-day Shinjuku City—just as World War I began to break out across Europe. Under the instruction of his father, a Zen Buddhist layman, he became familiar with Zen thought, and from a young age, read books on the subject and practiced zazen meditation.

He first encountered Christianity in middle school at Aoyama Gakuin, a school founded in Tokyo by Methodist missionaries in the late 19th century. At first, he felt a strong sense of aversion to Christian teaching, which challenged and even rejected the Zen philosophy he had grown up with, but the religion eventually piqued his interest. Izutsu, who was also a literary critic on the theory of poetry, loved reading the works of Junzaburo Nishiwaki, then a professor at the Keio University Faculty of Letters, which led Izutsu to enter the Keio University preparatory course in 1931. At first, he followed the path of his father, studying at the Faculty of Economics. Still, he could not bring himself to abandon his love of literature and eventually transferred to the English Department in the Faculty of Letters, where he studied under Prof. Nishiwaki. Recalling his first encounter with his mentor, Izutsu said, "When I first saw him [Prof. Nishiwaki] strolling through Mita Campus, my heart leaped in my chest." Izutsu is reported to have said that Prof. Nishiwaki was the only person he regarded as a mentor throughout his life.

Group photo taken in front of the Grand Lecture Hall on Mita Campus when Izutsu was a student. Izutsu is at far left, and his best friend Yasaburo Ikeda is second from right. Ikeda also enrolled in the Faculty of Economics but moved to the Faculty of Letters with Izutsu, later becoming a member of Keio's academic faculty alongside his old classmate. *

A Love of Language & Thirst for Knowledge Takes Izutsu Abroad

Izutsu attends Eranos in 1979 *

After graduating from university, Izutsu continued to serve as an assistant to Prof. Nishiwaki. Recognized for his extraordinary language skills, he became director at Keio's on-campus language school. He also worked as a researcher at the Keio Language Institute (later The Keio Institute of Cultural and Linguistic Studies), established in 1942 by Nishiwaki and other faculty. While working on the history of Islamic thought and research into Greek mysticism at the Faculty of Literature, he taught Russian literature in addition to several languages such as Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, and Hindustani.

In 1954, Izutsu became a professor at the Faculty of Letters and began teaching "Introduction to Linguistics," a course he took over from his esteemed mentor Prof. Junzaburo Nishiwaki. The novel content of the lecture was so popular that it was famous for running out of seats if students didn't arrive early. Jun Eto, a literary critic who was a student at the time, recalls, "I never had a course that gave me so much intellectual excitement with every lecture." Izutsu later summarized the content of this lecture in his English-language book Language and Magic: Studies in the Magical Function of Speech.

In 1959, Izutsu traveled abroad for the first time at the age of 45. With a scholarship from the Rockefeller Foundation, he spent two years visiting Islamic research centers in Lebanon, Egypt, Germany, France, and Canada, among other places. It was at this time, in 1961, that he was invited to serve as a visiting professor at Canada's McGill University, where he knew the academic faculty. In 1967, he began to participate in Eranos, a long-running interdisciplinary conference dedicated to humanistic and religious studies covering Eastern and Western philosophy, religion, art, and science. Among the experts invited to speak was Izutsu, who presented many lectures on Eastern philosophy and theology.

The Spirit of Toshihiko Izutsu Still Embodied at Keio University

In 1969, Izutsu retired from Keio and became a full professor at McGill University. With the opening of the Tehran Branch of McGill's Institute of Islamic Studies, he moved to Iran's capital city. After working as a professor at Iran's Royal Institute of the Study of Philosophy, he returned to Japan in the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. While most of Izutsu's writings had been authored in English until that point, he devoted himself to writing in Japanese until his death in 1993 in Kamakura, where he lived and authored books such as Islamic Culture.

The collection of books left by Izutsu at his Kamakura residence has since been entrusted to the Keio University Mita Media Center. Consisting of approximately 10,000 volumes of Japanese, Chinese, and Western-language books, the collection also includes roughly 3,700 volumes in Arabic as well as extremely valuable materials such as 90 Iranian lithographic books rarely seen outside of Iran.

In 2015, the Keio University Faculty of Letters established two academic awards named after Junzaburo Nishiwaki and Toshihiko Izutsu to commemorate the 125th anniversary of the faculty's founding. The Toshihiko Izutsu Prize is awarded to promising researchers who share Izutsu's spirit of inquiry, which spanned a wide range of academic disciplines that include philosophy, ethics, history, anthropology, archaeology, library sciences, sociology, psychology, pedagogy, and other human sciences. The prize aims to foster and encourage the next generation of scholars who can rival Izutsu's passion for knowledge in the 21st century.

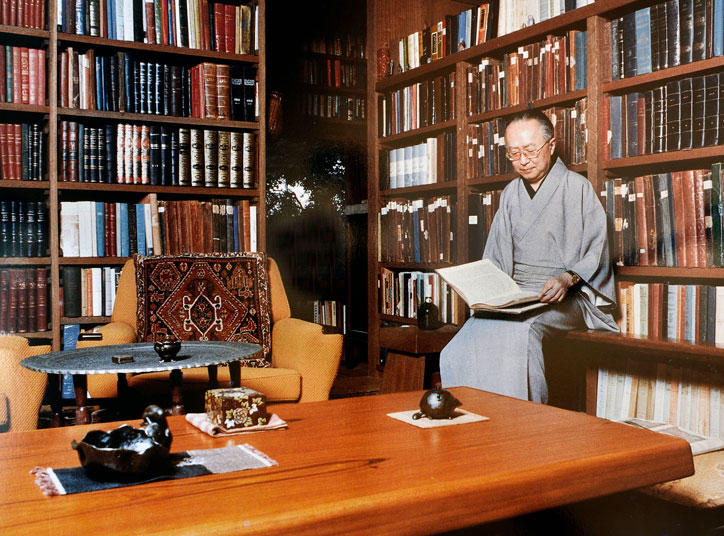

Izutsu in his study at Kita-Kamakura, where he spent his last years (photographed in 1980) *

*From "Toshihiko Izutsu Zammai," Keio University Press (October 2019).

*This article appeared in Stained Glass in the 2020 Summer edition (No. 307) of Juku.