Shingon Buddhism (真言宗, Shingon-shū) is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asia, originally spread from India to China through traveling monks such as Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra.

Known in Chinese as the Tangmi (唐密; the Esoteric School in Tang Dynasty of China), these esoteric teachings would later flourish in Japan under the auspices of a Buddhist monk named Kūkai (空海), who traveled to Tang China to acquire and request transmission of the esoteric teachings. For that reason, it is often called Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, or Orthodox Esoteric Buddhism.

The word shingon is the Japanese reading of the Chinese word 真言 (zhēnyán),[1] which is the translation of the Sanskrit word मन्त्र ("mantra").[2]

History[edit]

Painting of Kūkai from a set of scrolls depicting the first eight patriarchs of the Shingon school. Japan, Kamakura period (13th-14th centuries). Shingon Buddhist doctrine and teachings arose during the Heian period (794-1185) after a Buddhist monk named Kūkai traveled to China in 804 to study Esoteric Buddhist practices in the city of Xi'an (西安), then called Chang-an, at Azure Dragon Temple (青龍寺) under Huiguo, a favourite student of the legendary Amoghavajra. Huiguo was the first person to gather the still scattered elements of Indian and Chinese Esoteric Buddhism into a cohesive system, and Esoteric Buddhism was not yet considered to be a different sect or school at that time. Kūkai returned to Japan as Huiguo's lineage- and Dharma-successor. Shingon followers usually refer to Kūkai as Kōbō-Daishi (弘法大師, Great Master of the Propagation of Dharma) or Odaishi-sama (お大師様, The Great Master), the posthumous name given to him years after his death by Emperor Daigo.

Kūkai's early esoteric practices[edit]

Before he went to China, Kūkai had been an independent monk in Japan for over a decade. He was extremely well versed in Chinese literature, calligraphy and Buddhist texts. A Japanese monk named Gonsō (勤操) had brought back to Japan from China an esoteric mantra of the bodhisattva Ākāśagarbha, the Kokūzō-gumonjihō (虚空蔵求聞持法 "Ākāśagarbha Memory-Retention Practice") that had been translated from Sanskrit into Chinese by Śubhakarasiṃha (善無畏三蔵, Zenmui-Sanzō). When Kūkai was 22, he learned this mantra from Gonsō and regularly would go into the forests of Shikoku to practice it for long periods of time. He persevered in this mantra practice for seven years and mastered it. According to tradition, this practice brought him siddhis of superhuman memory retention and learning ability. Kūkai would later praise the power and efficacy of Kokuzō-Gumonjiho practice, crediting it with enabling him to remember all of Huiguo's teachings in only three months. Kūkai's respect for Ākāśagarbha was so great that he regarded him as his honzon (本尊) for the rest of his life.

It was also during this period of intense mantra practice that Kūkai dreamt of a man telling him to seek out the Mahavairocana Tantra for the doctrine that he sought. The Mahavairocana Tantra had only recently been made available in Japan. He was able to obtain a copy in Chinese but large portions were in Sanskrit in the Siddhaṃ script, which he did not know, and even the Chinese portions were too arcane for him to understand. He believed that this teaching was a door to the truth he sought, but he was unable to fully comprehend it and no one in Japan could help him. Thus, Kūkai resolved to travel to China to spend the time necessary to fully understand the Mahavairocana Tantra.

Kūkai's studies in China[edit]

When Kūkai reached China and first met Huiguo on the fifth month of 805, Huiguo was age sixty and on the verge of death from a long spate of illness. Huiguo exclaimed to Kūkai in Chinese (in paraphrase), "At last, you have come! I have been waiting for you! Quickly, prepare yourself for initiation into the mandalas!" Huiguo had foreseen that Esoteric Buddhism would not survive in India and China in the near future and that it was Kukai's destiny to see it continue in Japan. In the short space of three months, Huiguo initiated and taught Kūkai everything he knew on the doctrines and practices of the Mandala of the Two Realms as well as mastery of Sanskrit and (presumably to be able to communicate with Master Huiguo) Chinese. Huiguo declared Kūkai to be his final disciple and proclaimed him a Dharma successor, giving the lineage name Henjō-Kongō (Chinese: 遍照金剛; pinyin: Biànzhào Jīngāng) "All-Illuminating Vajra".

In the twelfth month of 805, Huiguo died and was buried next to his master, Amoghavajra. More than one thousand of his disciples gathered for his funeral. The honour of writing his funerary inscription on their behalf was given to Kūkai.

Kukai returned to Japan after Huiguo's death. If he had not, Shingon Esoteric Buddhism might not have survived; 35 years after Huiguo's death in the year 840, Emperor Wuzong of Tang assumed the throne. An avid Daoist, Wuzong despised Buddhism and considered the sangha useless tax-evaders. In 845, he ordered the destruction of 4600 vihara and 40,000 temples. Around 250,000 Buddhist monks and nuns had to give up their monastic lives. Wuzong stated that Buddhism was an alien religion and promoted Daoism zealously as the ethnic religion of the Han Chinese. Although Wuzong was soon assassinated by his own inner circle, the damage had been done. Chinese Buddhism, especially Esoteric practices, never fully recovered from the persecution, and esoteric elements were infused into other Buddhist sects and traditions.

After Kūkai's return to Japan[edit]

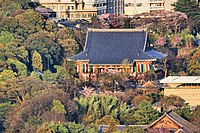

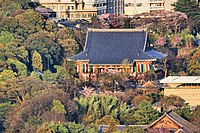

The main building of Shinsenen, a Shingon temple in Kyoto founded by Kūkai in 824 After returning to Japan, Kūkai collated and systematized all that he had learned from Huiguo into a cohesive doctrine of pure esoteric Buddhism that would become the basis for his school. Kūkai did not establish his teachings as a separate school; it was Emperor Junna, who favoured Kūkai and Esoteric Buddhism, who coined the term Shingon-Shū (真言宗, Mantra School) in an imperial decree which officially declared Tō-ji (東寺) in Kyoto an Esoteric temple that would perform official rites for the state. Kūkai actively took on disciples and offered transmission until his death in 835 at the age of 61.

Kūkai's first established monastery was in Mount Kōya (高野山), which has since become the base and a place of spiritual retreat for Shingon practitioners. Shingon enjoyed immense popularity during the Heian period (平安時代), particularly among the nobility, and contributed greatly to the art and literature of the time, influencing other communities such as the Tendai (天台宗) on Mount Hiei (比叡山).[3]

Shingon's emphasis on ritual found support in the Kyoto nobility, particularly the Fujiwara clan (藤原氏). This favour allotted Shingon several politically powerful temples in the capital, where rituals for the Imperial Family and nation were regularly performed. Many of these temples – Tō-ji and Daigo-ji (醍醐寺) in the south of Kyōto and Jingo-ji (神護寺) and Ninna-ji (仁和寺) in the northwest – became ritual centers establishing their own particular ritual lineages.

Like the Tendai School, which branched into the Jōdo-shū (浄土宗) and Nichiren Buddhism (日蓮系諸宗派, Nichiren-kei sho shūha) during the Kamakura period, Shingon divided into two major schools – the old school, Kogi Shingon (古義真言宗, Ancient Shingon school), and the new school, Shingi Shingon (新義真言宗, Reformed Shingon school).

This division primarily arose out of a political dispute between Kakuban (覚鑁), known posthumously as Kōgyō-Daishi (興教大師), and his faction of priests centered at the Denbō-in (伝法院) and the leadership at Kongōbu-ji (金剛峰寺), the head of Mount Kōya and the authority in teaching esoteric practices in general. Kakuban, who was originally ordained at Ninna-ji (仁和寺) in Kyōto, studied at several temple-centers including the Tendai complex at Onjō-ji (園城寺) before going to Mount Kōya. Through his connections he managed to gain the favour of high-ranking nobles in Kyoto, which helped him to be appointed abbot of Mount Kōya. The leadership at Kongōbuji, however, opposed the appointment on the premise that Kakuban had not originally been ordained on Mount Kōya.

After several conflicts, Kakuban and his faction of priests left the mountain for Mount Negoro (根来山) to the northwest, where they constructed a new temple complex now known as Negoro-ji (根来寺). After the death of Kakuban in 1143, the Negoro faction returned to Mount Kōya. However, in 1288, the conflict between Kongōbuji and the Denbō-in came to a head once again. Led by Raiyu, the Denbō-in priests once again left Mount Kōya, this time establishing their headquarters on Mount Negoro. This exodus marked the beginning of the Shingi Shingon School at Mount Negoro, which was the center of Shingi Shingon until it was sacked by daimyō Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉) in 1585.

Lineage[edit]

The Shingon lineage is an ancient transmission of esoteric Buddhist doctrine that began in India and then spread to China and Japan. Shingon is the name of this lineage in Japan, but there are also esoteric schools in China, Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong that consider themselves part of this lineage (as the originators of the Esoteric teachings) and universally recognize Kūkai as their eighth patriarch. This is why sometimes the term "Orthodox Esoteric Buddhism" is used instead.

Shingon or Orthodox Esoteric Buddhism maintains that the expounder of the doctrine was originally the Universal Buddha Vairocana, but the first human to receive the doctrine was Nagarjuna in India. The tradition recognizes two groups of eight great patriarchs – one group of lineage holders and one group of great expounders of the doctrine.

- The Eight Great Lineage Patriarchs (Fuho-Hasso 付法八祖)

- The Eight Great Doctrine-Expounding Patriarchs (Denji-Hasso 伝持八祖)

Doctrines[edit]

The teachings of Shingon are based on early Buddhist tantras, the Mahāvairocana Sūtra (大日経, Dainichi-kyō), the Vajraśekhara Sūtra (金剛頂経, Kongōchō-kyō), the Prajñāpāramitā Naya Sūtra (般若理趣経, Hannya Rishu-kyō), and the Susiddhikara Sūtra (蘇悉地経, Soshitsuji-kyō). These are the four principal texts of Esoteric Buddhism and are all tantras, not sutras, despite their names.

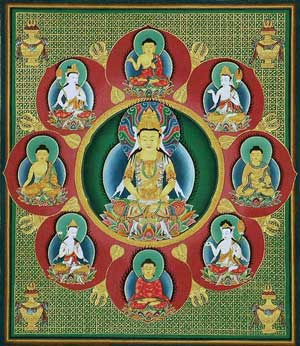

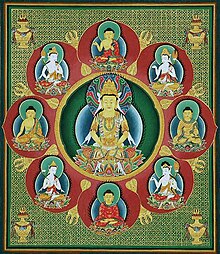

The mystical Vairocana and Vajraśekhara Tantras are expressed in the two main mandalas of Shingon, the Mandala of the Two Realms – The Womb Realm (Sanskrit: Garbhadhātu; Japanese: 胎蔵界曼荼羅, romanized: Taizōkai) mandala and the Diamond Realm (Sanskrit: Vajradhātu; Japanese: 金剛界曼荼羅, romanized: Kongōkai) mandala.[2] These two mandalas are considered to be a compact expression of the entirety of the Dharma, and form the root of Buddhism. In Shingon temples, these two mandalas are always mounted one on each side of the central altar.

The Susiddhikara Sūtra is largely a compendium of rituals. Tantric Buddhism is concerned with the rituals and meditative practices that lead to enlightenment. According to Shingon doctrine, enlightenment is not a distant, foreign reality that can take aeons to approach but a real possibility within this very life,[4] based on the spiritual potential of every living being, known generally as Buddha-nature. If cultivated, this luminous nature manifests as innate wisdom. With the help of a genuine teacher and through proper training of the body, speech, and mind, i.e. "The Three Mysteries" (三密, Sanmitsu), one can reclaim and liberate this enlightened capacity for the benefit of oneself and others.

Kūkai systematized and categorized the teachings he inherited from Huiguo into ten bhūmis or "stages of spiritual realization".

Relationship to Vajrayāna[edit]

When the teachings of Shingon Buddhism were brought to Japan, Esoteric Buddhism was still in its early stages in India. At this time, the terms Vajrayāna ("Diamond Vehicle") and Mantrayāna ("Mantra Vehicle") were not used for Esoteric Buddhist teachings.[5] Instead, esoteric teachings were more typically referred to as Mantranaya, or the "Mantra System." According to Paul Williams, Mantranaya is the more appropriate term to describe the self-perception of early Esoteric Buddhism.[5]

The primary difference between Shingon and Tibetan Buddhism is that there is no Inner Tantra or Anuttarayoga Tantra in Shingon. Shingon has what corresponds to the Kriyā, Caryā, and Yoga classes of tantras in Tibetan Buddhism. The Tibetan system of classifying tantras into four classes is not used in Shingon.

Anuttarayoga Tantras such as the Yamantaka Tantra, Hevajra Tantra, Mahamaya Tantra, Cakrasaṃvara Tantra, and the Kalachakra Tantra were developed at a later period of Esoteric Buddhism and are not used in Shingon.

Esoteric vs exoteric[edit]

He wrote at length on the difference between exoteric, mainstream Mahayana Buddhism and esoteric Tantric Buddhism. The differences between exoteric and esoteric can be summarised:

- Esoteric teachings are preached by the Dharmakaya (法身, Hosshin) Buddha, who Kūkai identifies as Vairocana (大日如來, Dainichi Nyorai). Exoteric teachings are preached by the Nirmanakaya (応身, Ōjin) Buddha, which in our world and aeon, is the historical Gautama Buddha (釈迦牟尼, Shakamuni) or one of the Sambhoghakaya (報身, Hōjin) Buddhas.

- Exoteric Buddhism holds that the ultimate state of Buddhahood is ineffable, and that nothing can be said of it. Esoteric Buddhism holds that while nothing can be said of it verbally, it is readily communicated via esoteric rituals which involve the use of mantras, mudras, and mandalas.

- Kūkai held that exoteric doctrines were merely upāya "skillful means" teachings on the part of the Buddhas to help beings according to their capacity to understand the Truth. The esoteric doctrines, in comparison, are the Truth itself and are a direct communication of the inner experience of the Dharmakaya's enlightenment. When Gautama Buddha attained enlightenment in his earthly Nirmanakaya, he realized that the Dharmakaya is actually reality in its totality and that totality is Vairocana.

- Some exoteric schools in the late Nara and early Heian period Japan held (or were portrayed by Shingon adherents as holding) that attaining Buddhahood is possible but requires a huge amount of time (three incalculable aeons) of practice to achieve, whereas esoteric Buddhism teaches that Buddhahood can be attained in this lifetime by anyone.

Kūkai held, along with the Chinese Huayan school (華嚴, Kegon) and the Tendai schools, that all phenomena could be expressed as 'letters' in a 'World-Text'. Mantra, mudra, and mandala are special because they constitute the 'language' through which the Dharmakāya (i.e. Reality itself) communicates. Although portrayed through the use of anthropomorphic metaphors, Shingon does not see the Dharmakaya Buddha as a separate entity standing apart from the universe. Instead, the deity is the universe properly understood: the union of emptiness, Buddha nature, and all phenomena. Kūkai wrote that "the great Self embraces in itself each and all existences".[6]

Mahavairocana Tathagata[edit]

In Shingon, Mahavairocana Tathagata (大日如來) is the universal or Adi-Buddha that is the basis of all phenomena, present in each and all of them, and not existing independently or externally to them. The goal of Shingon is the realization that one's nature is identical with Mahavairocana, a goal that is achieved through initiation, meditation and esoteric ritual practices. This realization depends on receiving the secret doctrines of Shingon, transmitted orally to initiates by the school's masters. The "Three Mysteries" of body, speech, and mind participate simultaneously in the subsequent process of revealing one's nature: the body through devotional gestures (mudra) and the use of ritual instruments, speech through sacred formulas (mantra), and mind through meditation.

Shingon places an emphasis on the Thirteen Buddhas (十三仏, Jūsanbutsu),[7] a grouping of various buddhas and bodhisattvas; however this is purely for lay Buddhist practice (especially during funeral rites) and Shingon priests generally make devotions to more than just the Thirteen Buddhas.

Mahavairocana is the Universal Principle which underlies all Buddhist teachings, according to Shingon Buddhism, so other Buddhist figures can be thought of as manifestations with certain roles and attributes. Kūkai wrote that "the great Self is one, yet can be many".[8] Each Buddhist figure is symbolized by its own Sanskrit "seed" letter.

Practices and features[edit]

A typical Shingon shrine set up for priests, with Vairocana at the center of the shrine, and the Womb Realm (Taizokai) and Diamond Realm (Kongokai) mandalas. 1:20Video showing prayer service at Kōshō-ji in Nagoya. A monk is rhythmically beating a drum while chanting sutras. One feature that Shingon shares in common with Tendai, the only other school with esoteric teachings in Japan, is the use of bīja or seed-syllables in Sanskrit written in the Siddhaṃ alphabet along with anthropomorphic and symbolic representations to express Buddhist deities in their mandalas.

There are four types of mandalas:

- Mahāmaṇḍala (大曼荼羅, Large Mandala)

- Bīja- or Dharmamaṇḍala (法曼荼羅)

- Samayamaṇḍala (三昧耶曼荼羅), representations of the vows of the deities in the form of articles they hold or their mudras

- Karmamaṇḍala (羯磨曼荼羅) representing the activities of the deities in the three-dimensional form of statues, etc.

The Siddhaṃ alphabet (Shittan 悉曇, Bonji 梵字) is used to write mantras. A core meditative practice of Shingon is Ajikan (阿字觀) "meditating on the letter a" written using the Siddhaṃ alphabet. Other Shingon meditations are Gachirinkan (月輪觀, "Full Moon visualization"), Gojigonjingan (五字嚴身觀, "Visualization of the Five Elements arrayed in The Body" from the Mahavairocana Tantra) and Gosōjōjingan (五相成身觀, Pañcābhisaṃbodhi "Series of Five Meditations to attain Buddhahood") from the Vajraśekhara Sutra.

The essence of Shingon practice is to experience Reality by emulating the inner realization of the Dharmakaya through the meditative ritual use of mantra, mudra and visualization, i.e. "The Three Mysteries" (Sanmitsu 三密). All Shingon followers gradually develop a teacher-student relationship, formal or informal, whereby a teacher learns the disposition of the student and teaches practices accordingly. For lay practitioners, there is no initiation ceremony beyond the Kechien Kanjō (結縁灌頂), which aims to help create the bond between the follower and Mahavairocana Buddha. It is normally offered only at Mount Kōya twice a year, but it can also be offered by larger temples under masters permitted to transmit the abhiseka. It is not required for all laypersons to take, and no assigned practices are given.

Discipline[edit]

In the case of disciples wishing to train to become a Shingon ācārya or "teacher" (Ajari 阿闍梨, from ācārya Sanskrit: आचार्य), it requires a period of academic study and religious discipline, or formal training in a temple for a longer period of time, after having already received novice ordination and monastic precepts, and full completion of the rigorous four-fold preliminary training and retreat known as Shido Kegyō (四度加行).[9] Only then can the practitioner be able to undergo steps for training, examination, and finally abhiṣeka to be certified as a Shingon acarya and continue to study more advanced practices. In either case, the stress is on finding a qualified and willing mentor who will guide the practitioner through the practice at a gradual pace. An acharya in Shingon is a committed and experienced teacher who is authorized to guide and teach practitioners. One must be an acharya for a number of years at least before one can request to be tested at Mount Kōya for the possibility to qualify as a mahācārya or "great teacher" (Dento Dai-Ajari 傳燈大阿闍梨), the highest rank of Shingon practice and a qualified grand master. However, it should be noticed that such a tradition is only in Koyasan sect. In other shingon sects, an Ajari who gives Kanjo is only called a Dai-Ajari or a Dento Dai-Ajari and has no special meaning like Koyasan sect. In the first place, Koyasan's Dharma Lineage became extinct immediately after Kūkai, and the current lineage of Koyasan sect is transplanted from Mandala-ji temple (曼荼羅寺) in Kyoto by Meizan (明算, 1021-1106). It implies that the tradition to become a Dento Dai-Ajari was created after Meizan, not an original tradition of Shingon. Furthermore, Meizan was not given the deepest teaching, so Yukai (宥快, 1345-1416), a great scholar at Koyasan, considered Anshoji-Ryu Lineage, rather than the Chuin-Ryu Lineage, to be the orthodox Shingon lineage.[10] Apart from the supplication of prayers and reading of sutras, there are mantras and ritualistic meditative techniques that are available for any laypersons to practice on their own under the supervision of an Ajari. However, any esoteric practices require the devotee to undergo abhiṣeka (initiation) (Kanjō 灌頂) into each of these practices under the guidance of a qualified acharya before they may begin to learn and practice them. As with all schools of Esoteric Buddhism, great emphasis is placed on initiation and oral transmission of teachings from teacher to student.

Goma fire ritual[edit]

A goma ritual performed at Chushinkoji Temple in Japan The goma (護摩) ritual of consecrated fire is unique to Esoteric Buddhism and is the most recognizable ritual defining Shingon among regular Japanese persons today. It stems from the Vedic homa ritual and is performed by qualified priests and acharyas for the benefit of individuals, the state or all sentient beings in general. The consecrated fire is believed to have a powerful cleansing effect spiritually and psychologically. The central deity invoked in this ritual is usually Acala (Fudō Myōō 不動明王). The ritual is performed for the purpose of destroying detrimental thoughts and desires, and for the making of secular requests and blessings. In most Shingon temples, this ritual is performed daily in the morning or the afternoon. Larger scale ceremonies often include the constant beating of taiko drums and mass chanting of the mantra of Acala by priests and lay practitioners. Flames can sometimes reach a few meters high. The combination of the ritual's visuals and sounds can be trance-inducing.

Adopting the practice from Shingon Buddhism, adherents the syncretic Japanese religion of Shugendō (修験道) also practice the goma ritual, of which two types are prominent: the saido dai goma and hashiramoto goma rituals.[11]

Secrecy[edit]

Today, there are very few books on Shingon in the West and until the 1940s, not a single book on Shingon had ever been published anywhere in the world, not even in Japan. Since this lineage was brought over to Japan from Tang China over 1100 years ago, its doctrines have always been closely guarded secrets, passed down orally through an initiatic chain and never written down. Throughout the centuries, except for the initiated, most of the Japanese common folk knew little of its secretive doctrines and of the monks of this "Mantra School" except that besides performing the usual priestly duties of prayers, blessings and funeral rites for the public, they practiced only Mikkyō "secret teachings", in stark contrast to all other Buddhist schools, and were called upon to perform mystical rituals that were supposedly able to summon rain, improve harvests, exorcise demons, avert natural disasters, heal the sick and protect the state. The most powerful ones were thought to be able to render entire armies useless.

Even though Tendai also incorporates esoteric teachings in its doctrines, it is still essentially an exoteric Mahayana school. Some exoteric texts are venerated and studied in Shingon as they are the foundation of Mahayana philosophy but the core teachings and texts of Shingon are purely esoteric. From the lack of written material, inaccessibility of its teachings to non-initiates, language barriers and the difficulty of finding qualified teachers outside Japan, Shingon is in all likelihood the most secretive and least understood school of Buddhism in the world.

Pantheon[edit]

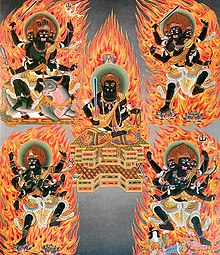

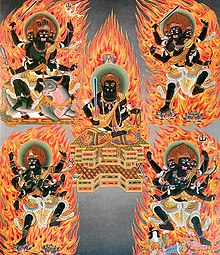

Acalanatha, the wrathful manifestation of Mahavairocana, and the principal deity invoked during the goma ritual. A large number of deities of Vedic, Hindu and Indo-Aryan origins have been incorporated into Mahayana Buddhism and this synthesis is especially prominent in Esoteric Buddhism. Many of these deities have vital roles as they are regularly invoked by the practitioner for various rituals and homas/pujas. In fact, it is ironic that the worship of Vedic-era deities, especially Indra (Taishakuten 帝釈天), the "King of the Heavens," has declined so much in India but is yet so highly revered in Japan that there are probably more temples devoted to him there than there are in India. Chinese Taoist and Japanese Shinto deities were also assimilated into Mahayana Buddhism as deva-class beings. For example, to Chinese Mahayana Buddhists, Indra (synonymous with Śakra) is the Jade Emperor of Taoism. Agni (Katen 火天), another Vedic deity, is invoked at the start of every Shingon Goma Ritual. The average Japanese person may not know the names Saraswati or Indra but Benzaiten (弁財天; Saraswati) and Taishakuten (帝釈天; Indra) are household names that every Japanese person knows.

In Orthodox Esoteric Buddhism, divine beings are grouped into six classes.

The Five Great Wisdom Kings

The Five Wisdom Kings is the most important grouping of Wisdom Kings in Esoteric Buddhism. The Five Great Wisdom Kings are wrathful manifestations of the Five Dhyani Buddhas.

Other well-known Wisdom Kings

The Twelve Guardian Deities (Deva)

- Agni (Katen 火天) – Lord of Fire; Guardian of the South East

- Brahmā (Bonten 梵天) – Lord of the Heavens; Guardian of the Heavens (upward direction)

- Chandra (Gatten 月天) – Lord of the Moon

- Indra (Taishakuten 帝釈天) – Lord of the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven and The Thirty Three Devas; Guardian of the East

- Prthivi or Bhūmī-Devī (Jiten 地天) – Lord of the Earth; Guardian of the Earth (downward direction)

- Rakshasa (Rasetsuten 羅刹天) – Lord of Demons; Guardian of the South West (converted Buddhist rakshasas)

- Shiva or Maheshvara (Daijizaiten 大自在天 or Ishanaten 伊舎那天) – Lord of The Desire Realms; Guardian of the North East

- Sūrya (Nitten 日天) – Lord of the Sun

- Vaishravana (Bishamonten 毘沙門天 or Tamonten 多聞天) – Lord of Wealth; Guardian of the North

- Varuṇa (Suiten 水天) – Lord of Water; Guardian of the West

- Vāyu (Fūten 風天)- Lord of Wind; Guardian of the North West

- Yama (Emmaten 焔魔天) – Lord of the Underworld; Guardian of the South

Other Important Deities (Deva)

Branches[edit]

Located in Kyoto, Japan, Daigo-ji is the head temple of the Daigo-ha branch of Shingon Buddhism.

Chishaku-in is the head temple of Shingon-shū Chizan-ha

Hasedera in Sakurai, Nara is the head temple of Shingon-shū Buzan-ha - The Orthodox (Kogi) Shingon School (古義真言宗)

- Kōyasan (高野山真言宗)

- Chuin-Ryu Lineage (中院流, decided after World War II[clarification needed])

- Nishinoin-Ryu Nozen-Gata Kōya-Sojo Lineage (西院流能禅方高野相承, already extinct)

- Nishinoin-Ryu Genyu-Gata Kōya-Sojo Lineage (西院流元瑜方高野相承, already extinct)

- Nishinoin-Ryu Enyu-Gata Kōya-Sojo Lineage (西院流円祐方高野相承, already extinct)

- Samboin-Ryu Kenjin-Gata Kōya-Sojo Lineage (三宝院流憲深方高野相承, almost extinct)

- Samboin-Ryu Ikyo-Gata Kōya-Sojo Lineage (三宝院流意教方, almost extinct)

- Samboin-Ryu Shingen-Gata Kōya-Sojo Lineage (三宝院流真源相承, almost extinct)

- Anshoji-Ryu Lineage (安祥寺流, almost extinct)

- Chuinhon-Ryu Lineage (中院本流, almost extinct)

- Jimyoin-Ryu Lineage (持明院流, almost extinct)

- Reiunji-ha (真言宗霊雲寺派)

- Shinanshoji-Ryu Lineage (新安祥寺流, established by Jogon (浄厳, 1639 - 1702))

- Zentsūji-ha (真言宗善通寺派)

- Jizoin-Ryu Lineage (地蔵院流, already extinct)

- Zuishinin-Ryu Lineage (随心院流, since Meiji era)

- Daigo-ha (真言宗醍醐派)

- Samboin-Ryu Jozei-Gata Lineage (三宝院流定済方)

- Samboin-Ryu Kenjin-Gata Lineage (三宝院流憲深方, already extinct)

- Rishoin-Ryu Lineage (理性院流, already extinct)

- Kongoouin-Ryu Lineage (金剛王院流, already extinct)

- Jizoin-Ryu Lineage (地蔵院流, already extinct)

- Omuro-ha (真言宗御室派)

- Nishinoin-Ryu Enyu-Gata Lineage (西院流円祐方)

- Shingon-Ritsu (真言律宗)

- Saidaiji-Ryu Lineage (already extinct) (西大寺流)

- Chuin-Ryu Lineage (中院流, same as Kōyasan)

- Daikakuji-ha (真言宗大覚寺派)

- Samboin-Ryu Kenjin-Gata Lineage (三宝院流憲深方, already extinct)

- Hojuin-Ryu Lineage (保寿院流, since Heisei era)

- Sennyūji-ha (真言宗泉涌寺派)

- Zuishinin-Ryu Lineage (随心院流)

- Yamashina-ha (真言宗山階派)

- Kanshuji-Ryu Lineage (観修寺流)

- Shigisan (信貴山真言宗)

- Chuin-Ryu Lineage (中院流, same as Kōyasan)

- Nakayamadera-ha (真言宗中山寺派)

- Chuin-Ryu Lineage (中院流, same as Kōyasan)

- Sanbōshū (真言三宝宗)

- Chuin-Ryu Lineage (中院流, same as Kōyasan)

- Sumadera-ha (真言宗須磨寺派)

- Chuin-Ryu Lineage (中院流, same as Kōyasan)

- Tōji-ha (真言宗東寺派)

- Nishinoin-Ryu Nozen-Gata Lineage (西院流能禅方)

- The Reformed (Shingi) Shingon School (新義真言宗)

- Shingon-shu Negoroji (根来寺)

- Chushoin-Ryu Lineage (中性院流)

- Chizan-ha (真言宗智山派)

- Chushoin-Ryu Lineage (中性院流)

- Samboin-Ryu Nisshu-Sojo (三宝院流日秀相承)

- Buzan-ha (真言宗豊山派)

- Samboin-Ryu Kenjin-Gata Lineage (三宝院流憲深方, already extinct)

- Chushoin-Ryu Lineage (中性院流)

- Daidenboin-Ryu Lineage (大伝法院流, since Meiji era)

- Kokubunji-ha (真言宗国分寺派)

- Inunaki-ha (真言宗犬鳴派)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Zhēnyán". Cengage – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kiyota, Minoru (1987). "Shingon Mikkyō's Twofold Maṇḍala: Paradoxes and Integration". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 10 (1): 91–92. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014.

- ^ Caiger, Mason. A History of Japan, Revised Ed. pp. 106–107.

- ^ Inagaki Hisao (1972). "Kukai's Sokushin-Jobutsu-Gi" (Principle of Attaining Buddhahood with the Present Body), Asia Major (New Series) 17 (2), 190-215

- ^ Jump up to:a b Williams, Paul, and Tribe, Anthony. Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition. 2000. p. 271

- ^ Hakeda, Yushito S. (1972). Kūkai: Major Works. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. pp. 258. ISBN 0-231-03627-2.

- ^ Shingon Buddhist International Institute. "Jusan Butsu – The Thirteen Buddhas of the Shingon School". Archived from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ Hakeda, Yushoto S. (1972). Kūkai: Major Works. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. pp. 258. ISBN 0-231-03627-2.

- ^ Sharf, Robert, H. (2003). Thinking through Shingon Ritual, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 26 (1), 59-62

- ^ Koda, Yuun (1982). Hoju Nimon no Chuin-Ryu, Journal of esoteric Buddhism 139, pp.27-42. PDF

- ^ "Ascetic Practice of Fire". Shugendo. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

Bibliography[edit]

- Giebel, Rolf W.; Todaro, Dale A.; transl. (2004). Shingon Texts, Berkeley, Calif.: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 1886439249

- Giebel, Rolf, transl. (2006), The Vairocanābhisaṃbodhi Sutra, Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, Berkeley, ISBN 978-1-886439-32-0

- Giebel, Rolf, transl. (2006). Two Esoteric Sutras: The Adamantine Pinnacle Sutra (T 18, no 865), The Susiddhikara Sutra (T 18, no 893), Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 1-886439-15-X

- Hakeda, Yoshito S., transl. (1972). Kukai: Major Works, Translated, With an Account of His Life and a Study of His Thought, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-03627-2.

- Matsunaga, Daigan; and Matsunaga, Alicia (1974). Foundation of Japanese Buddhism, Vol. I: The Aristocratic Age. Buddhist Books International, Los Angeles und Tokio. ISBN 0-914910-25-6.

- Kiyota, Minoru (1978). Shingon Buddhism: Theory and Practice. Los Angeles/Tokyo: Buddhist Books International.

- Payne, Richard K. (2004). "Ritual Syntax and Cognitive Theory", Pacific World Journal, Third Series, No 6, 105–227.

- Toki, Hôryû; Kawamura, Seiichi, tr, (1899). "Si-do-in-dzou; gestes de l'officiant dans les cérémonies mystiques des sectes Tendaï et Singon", Paris, E. Leroux.

- Yamasaki, Taiko (1988). Shingon: Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, Boston/London: Shambala Publications.

- Miyata, Taisen (1998). A Study of the Ritual Mudras in the Shingon Tradition and Their Symbolism.

- Dreitlein, Eijo (2011). Shido Kegyo Shidai, Japan.

- Dreitlein, Eijo (2011). Beginner's Handbook for the Shido Kegyo of Chuin-ryu, Japan.

- Maeda, Shuwa (2019). The Ritual Books of Four Preliminary Practices: Sambo-in Lineage Kenjin School, Japan.

- Chandra, Lokesh (2003). The Esoteric Iconography of Japanese Mandalas, International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan, New Delhi, ISBN 81-86471-93-6

- Arai, Yusei (1997). Koyasan Shingon Buddhism: A Handbook for Followers, Japan: Koyasan Shingon Mission, ISBN 4-9900581-1-9.

External links[edit]

Temple 7 of the "13 Buddhas of Osaka" pilgrimage, Senko-ji, which houses a short version of the "88 places of Shikoku." From Gereon Kopf

Temple 7 of the "13 Buddhas of Osaka" pilgrimage, Senko-ji, which houses a short version of the "88 places of Shikoku." From Gereon Kopf "Womb World Mandala," attributed to Kukai. From Gereon Kopf

"Womb World Mandala," attributed to Kukai. From Gereon Kopf Temple 51, Ishite-ji, Shikoku. From Gereon Kopf

Temple 51, Ishite-ji, Shikoku. From Gereon Kopf Statue of Kukai at Muryokoin, Mt. Koya. From Gereon Kopf

Statue of Kukai at Muryokoin, Mt. Koya. From Gereon Kopf