Showing Results For Buddhism In Japan

Results: 1, 2, 3, 4

Shinto: The Way of, to, and with the Gods!

Exploring the Shinto tradition

Uploaded 19 Jun 2015

Read More

Humility, Faith, and Other-Power: Shinran’s "Tannisho"

The so-called sectarianism of Buddhism in Japan has...

Uploaded 20 Mar 2015

Read More

Walking with Kukai–Becoming a Buddha: Pilgrimage in Shingon...

A look at Master Kukai's influence on Japanese...

Uploaded 30 Jan 2015

Read More

The Variety of Practice in Soto Zen Buddhism

Dogen’s (1200–53) Soto Zen is known for its emphasis on...

Uploaded 10 Oct 2014

Read More

The Precept-bestowing Assembly at Eihei-ji

This is the first of a series of articles on Japanese...

Uploaded 29 Aug 2014

Read More

Results: 1, 2, 3, 4

===

Results: 1, 2, 3, 4

Meaning in the Face of Transience: Reflections of Socially Engaged...

Finding solace in impermanence

Uploaded 17 Jan 2018

Read More

One Face of Liberation: Buddhist Feminism in Japan

The Zen-inspired activism of Hiratsuka Raichō

Uploaded 30 Oct 2017

Read More

Who Am I — Self-discovery in Japanese Zen Practice

On the nature and purpose of selfless self-awareness

Uploaded 26 May 2017

Read More

Samurai and Monks: Lessons in Impermanence

Examining the Tale of Heike

Uploaded 24 Mar 2017

Read More

Why Meditate?

Understanding the transformative approaches to...

Uploaded 27 Jan 2017

Read More

Does a Philosopher Have Buddha-nature?

Dōgen's take on the enlightened nature within us all

Uploaded 4 Nov 2016

Read More

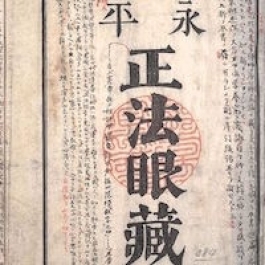

How to Read Japanese Buddhist Texts?

Approaching historical Buddhist texts

Uploaded 9 Sep 2016

Read More

Spirituality as the Transformation of Daily Life: Living Buddhism in 21st...

The changing face of Japanese Buddhism

Uploaded 20 May 2016

Read More

How to Face Death - Pilgrimages and Death Rituals in Japanese...

Consoling those who have lost a loved one and...

Uploaded 15 Jan 2016

Read More

Drinking Tea—Meeting the Buddha

Gereon Kopf on Buddhism in the tea ceremony

Uploaded 18 Sep 2015

Read More

Results: 1, 2, 3, 4

===

Japanese Buddhism 101: The Search for the Buddha

Doctrinal Buddhist beliefs and practices in Japan

Uploaded 23 Aug 2019

Read More

Death and Dying in Japanese Buddhism

Engaging with mortality

Uploaded 29 Jun 2019

Read More

The Metaphorical Sword

Expressions of the Buddhadharma in the...

Uploaded 22 May 2019

Read More

Who Will I Be? Japanese Buddhist Conceptions of the Afterlife

Concepts of self and no-self at the end of life

Uploaded 30 Mar 2019

Read More

“Beauty that Floats on Mud”

Illuminations of the Lotus Sutra

Uploaded 12 Jan 2019

Read More

What Use is Morality for Meditation?

The path to wisdom and compassion

Uploaded 26 Oct 2018

Read More

Who Is the Buddha?

Mythology and history in the Buddhadharma

Uploaded 17 Aug 2018

Read More

“This Mind is the Buddha”* — Being Religious (in Japan)

Between immanence and transcendence

Uploaded 30 Jun 2018

Read More

Expressions between Dogma and Silence: A Japanese Take on the Two Truths

Exploring two interpretations of a central Buddhist doctrine

Uploaded 20 Apr 2018

Read More

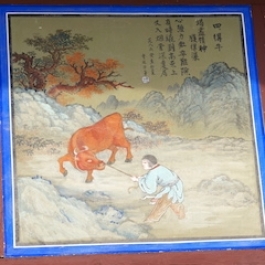

Becoming a Buddha – A Shingon Buddhist 10-step Program

Mapping the way from suffering to liberation

Uploaded 1 Mar 2018

Read More

===

Buddhist Death Rituals: For the Living – Not for the Dead

Exploring a unique Japanese ritual that skillfully aids...

Uploaded 8 Oct 2021

Read More

What or Who Is a Buddha?

Exploring the meaning of buddhahood in the Japanese...

Uploaded 10 Aug 2021

Read More

Art in Japanese Buddhism

An overview of artistic styles and forms in Japan

Uploaded 7 May 2021

Read More

The Zen Masters of the Rinzai Tradition

Beginning a series of essays on the Zen masters of Japan

Uploaded 24 Dec 2020

Read More

Does Artificial Intelligence have Buddha-nature?

If a bodhisattva can come in all forms, why not as a robot?

Uploaded 29 Oct 2020

Read More

Do I Need a Teacher to Practice Meditation?

Lessons from Zen on lineage, practice, and compassion

Uploaded 3 Sep 2020

Read More

Another Kind of Pilgrimage

What it means to walk the Buddha-way

Uploaded 19 Jun 2020

Read More

The Zen of Temples

A history of temple buildings in Japan

Uploaded 22 May 2020

Read More

Japanese Buddhist Poetry: Bearing the Weight of Being

Insight through skillful means into the depths of the human...

Uploaded 2 Mar 2020

Read More

Words Heal – Words Hurt

Our speech shows our true understanding as much as...

Uploaded 4 Dec 2019

Read More

Results: 1, 2, 3, 4

===

===

===

Temple 7 of the "13 Buddhas of Osaka" pilgrimage, Senko-ji, which houses a short version of the "88 places of Shikoku." From Gereon Kopf

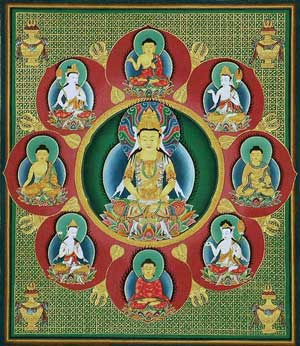

Temple 7 of the "13 Buddhas of Osaka" pilgrimage, Senko-ji, which houses a short version of the "88 places of Shikoku." From Gereon Kopf "Womb World Mandala," attributed to Kukai. From Gereon Kopf

"Womb World Mandala," attributed to Kukai. From Gereon Kopf Temple 51, Ishite-ji, Shikoku. From Gereon Kopf

Temple 51, Ishite-ji, Shikoku. From Gereon Kopf Statue of Kukai at Muryokoin, Mt. Koya. From Gereon Kopf

Statue of Kukai at Muryokoin, Mt. Koya. From Gereon Kopf