The Contemplative Life.

Exploring contemplative spirituality in the 21st Century...

HomeThe Traditions

Spiritual Practice

The Mystics

ComparativeMy BooksBlogSitting Groups

The Perennial Philosophy: Review

June 25, 2016 in Book Reviews, Comparative Mysticism, Aldous Huxley

===

Drawing from primary texts across the spectrum of the world's religious traditions, in The Perennial Philosophy Aldous Huxley synthesizes mystic thought in a variety of areas. Beginning with what the mystics believe about the nature of reality, Huxley goes on to show how this "Perennial Philosophy" plays itself out in their lives. A fantastic springboard for exploring primary contemplative texts, there is no better book for an introduction to world mysticism.

Overview: Huxley begins by defining the "philosophy of the mystics," what has been called, since Gottfried Leibniz, the Perennial Philosophy because it shows itself in religious traditions across the ages. In Huxley's words:

"Philosophia Perennis – the phrase was coined by Leibniz; but the thing – the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality; the ethic that places man's final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being – the thing is immemorial and universal."

Huxley's definition brings together Western personal/theistic thought and Eastern, mostly non-personal, thought into one statement. To speak roughly in the languages of West and East:

In Western terms: (1) There is a God who is the Source of existence, (2) God dwells at the core of each human soul, and (3) our ultimate destiny, if we choose it, is union with God.

In Eastern terms: (1) There is a Spiritual Ground of existence, (2) the core of each human soul is identical with the Spiritual Ground, and (3) our ultimate destiny, if we choose it, is absorption in the Ground.

Huxley spends his first two chapters, That Art Thou and The Nature of the Ground, expanding on this definition. In true mystic form, the nature of the Spiritual Ground which lies at the core of each created being is a mystery.

"What is the That to which the thou can discover itself to be akin? To this the fully developed Perennial Philosophy has at all times and in all places given fundamentally the same answer. The divine Ground of all existence is a spiritual Absolute, ineffable in terms of discursive thought, but (in certain circumstances) susceptible of being directly experienced and realized by the human being."

In other words, God can't be defined, He can only be experienced directly. That, my friends, is mysticism. The God whom the worshipper may have "known" through their religious texts, doctrine, and faith tradition, suddenly becomes "unknowable." The mystics are concerned almost exclusively with direct experience of God and how that experience transforms them; theology becomes a secondary matter. This has, historically, often put them at odds with the official religious institutions they come from.

After defining and expanding on the core philosophy of the mystics, Huxley spends the rest of the book looking at how this plays out in their lives. I'll briefly look at three of these chapters:

Mortification, Non-Attachment, Right Livelihood: The way to find God is to die to self. The goal of the mystic is simply to become an empty vessel through which God may work. Instead of identifying with the ego, the "I", the normal sense of self, the contemplative identifies with the divine "not-I," what is called the "Higher Self" in some traditions. The life of the contemplative is thus a life of self-denial, not because self-denial is a good in and of itself, but because it is the ego, our self-will, that separates us from a life of union with God.

고행, 비집착, 올바른 생계: 신을 찾는 방법은 자아를 죽이는 것입니다.

신비주의자의 목표는 단순히 하나님이 일하실 수 있는 빈 그릇이 되는 것입니다.

관조자는 자아, 즉 정상적인 자아 감각인 "나"와 동일시하는 대신에

일부 전통에서 "상위 자아"라고 불리는, 신성한 "나가 아닌 것"과 동일시합니다.

따라서 관상가의 삶은 극기의 삶이며,

극기는 그 자체로 선한 것이 아니라,

우리를 하느님과 일치하는 삶에서 분리시키는 것이 자아이고, 우리의 의지라는 것을 이해하는 것 이기 때문입니다.

The Miraculous: Here Huxley explores the existence of "miraculous events" and their connection to the mystics. These type of events – supernatural healings, psychic powers, etc. – are often associated with contemplatives. Surprisingly, their attitude towards the miraculous is one of indifference and can be summed up by a quote with which Huxley introduces the chapter:

"Can you walk on water? You have done no better than a straw. Can you fly in the air? You have done no better than a bluebottle. Conquer your heart; then you may become somebody."

– Ansari of Herat

It is salvation, deliverance, nirvana and how that experience can be lived out in the world that the contemplatives are interested in, not the cultivation of supernatural powers.

Contemplation, Action and Social Utility: The contemplatives believe that contemplation, the direct experience of God, is the ultimate end for which humanity is designed. Action in the world (good works, etc.) may prepare the soul for contemplation, but action is not an end in itself.

"In all the historic formulations of the Perennial Philosophy it is axiomatic that the end of human life is contemplation, or the direct and intuitive awareness of God; that action is the means to that end; that a society is good to the extent that it renders contemplation possible for its members; and that the existence of at least a minority of contemplatives is necessary for the well-being of any society."

Ironically, it is also the contemplative, the one who has purified himself of self-will, that will naturally perform true positive action in the world:

"...action that is 'taken away from the life of prayer' is action unenlightened by contact with Reality, uninspired and unguided; consequently it is apt to be ineffective and even harmful."

In other chapters, Huxley delves into personal temperament and how it affects religious action, spiritual exercises, the role of ritual and sacrament, and various related topics.

Personal Reflections: Some critics think that Huxley finds too much commonality and not enough diversity in world mysticism, that he "makes the pieces fit" what he believes is a common core. While there is certainly diversity in these traditions, I think Huxley does show that, while the mystics might not speak with one voice, they do often speak in harmony.

This book was life-changing for me. As I was coming out of conservative religion, it helped me hang on to the belief that religion may, in fact, point to something real. That even if all of my tightly held theology had been stripped away, I might still find God. Nihilism works for some people, but it clearly wasn't going to work for me. And that's where I would be if I hadn't found the contemplative versions of faith that are represented in this book.

One of the more fascinating ideas that I come back to from The Perennial Philosophy is the idea that "knowledge is a function of being." If we change ourselves by consciously "dying to self" and becoming selfless, we can change our "knowledge" or experience of the world. Instead of interpreting the world through the tainted lens of our own needs and wants, our self-interest, we begin to see the world with different eyes. And the mystics insist that if we can truly cleanse ourselves of our self-interest, the fruit will be a life of love, joy, and peace.

I can't recommend this book, or Huxley as an author, enough. If you are interested in world mysticism, start here.

The Perennial Tradition and Comparative Mysticism

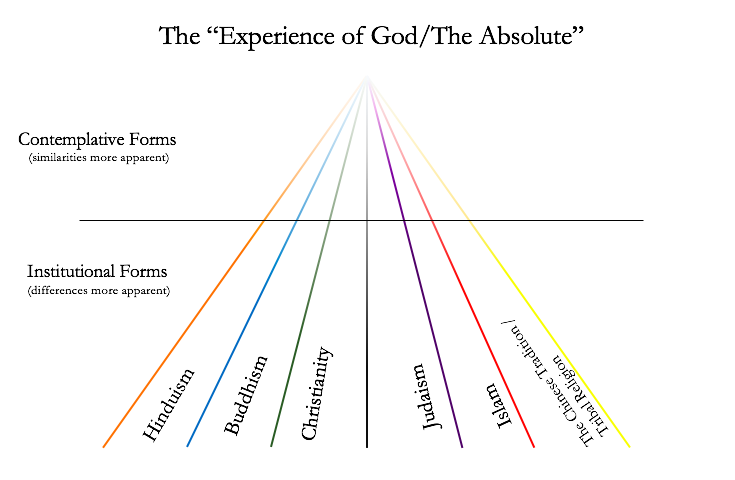

Mystic or contemplative strands of the world's religious traditions are sometimes grouped together and categorized in what has been called "The Perennial Tradition." The term perennial refers to the fact that the ideas associated with these contemplative versions of faith continue to arise, and show themselves throughout history, independent of religious tradition. On this theory, the perennial contemplative tradition is embedded within each individual religion – it is the "common denominator" among the diversity of religious thought.

The most famous treatment of the Perennial Tradition comes from Aldous Huxley. In his The Perennial Philosophy he defines the concept as follows:

"Philosophia Perennis: the phrase was coined by Leibniz; but the thing — the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality; the ethic that places man's final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being — the thing is immemorial and universal."

Or, put in more simplified terms:

(1) There is a God or Spiritual Reality that is the Source and Ground of Existence,

(2) this Spiritual Reality can be experienced within the soul of each created being, and

(3) our ultimate destiny, if we choose it, is to experientially know or unite ourselves with this Reality, and reflect this union in our lives.

One of the primary debates surrounding the Perennial Tradition is just how unified world mysticism actually is.

One of the primary debates surrounding the Perennial Tradition is just how unified world mysticism actually is.

On one hand, there are those who argue that Huxley and others create a false synthesis. That the mystic strands of each religious tradition are far more diverse than they are similar and can't reasonably be boiled down to a lowest common denominator.

On the other hand, there are those who, along with Huxley, see more unity than diversity and believe that we can fairly speak of "a mystic philosophy" or some kind of synthesis between traditions. The content on this site leans towards seeing unity among the traditions.