Erewhon

First edition cover | |

| Author | Samuel Butler |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Satire |

| Publisher | Trübner and Ballantyne |

Publication date | 1872 |

| Pages | 246 |

| OCLC | 2735354 |

| 823.8 | |

| LC Class | PR4349.B7 E7 1872 c. 1 |

| Followed by | Erewhon Revisited |

Erewhon: or, Over the Range (/ɛrɛhwɒn/[1]) is a novel by Samuel Butler which was first published anonymously in 1872,[2] set in a fictional country discovered and explored by the protagonist. Butler meant the title to be understood as the word "nowhere" backwards[citation needed] even though the letters "h" and "w" are transposed. The book is a satire on Victorian society.[3]

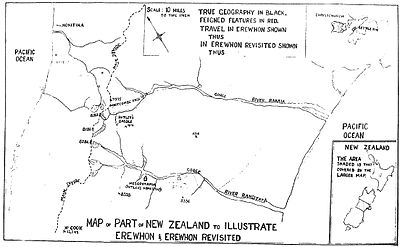

The first few chapters of the novel dealing with the discovery of Erewhon are in fact based on Butler's own experiences in New Zealand, where, as a young man, he worked as a sheep farmer on Mesopotamia Station for about four years (1860–64), and explored parts of the interior of the South Island and which he wrote about in his A First Year in Canterbury Settlement (1863).

The novel is one of the first to explore ideas of artificial intelligence, as influenced by Darwin's recently published On the Origin of Species (1859) and the machines developed out of the Industrial Revolution (late 18th to early 19th centuries). Specifically, it concerns itself, in the three-chapter "Book of the Machines", with the potentially dangerous ideas of machine consciousness and self-replicating machines.

Content[edit]

The greater part of the book consists of a description of Erewhon. The nature of this nation is intended to be ambiguous. At first glance, Erewhon appears to be a Utopia, yet it soon becomes clear that this is far from the case. Yet for all the failings of Erewhon, it is also clearly not a dystopia, such as that depicted in George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.

As a satirical utopia, Erewhon has sometimes been compared to Gulliver's Travels (1726), a classic novel by Jonathan Swift; the image of Utopia in this latter case also bears strong parallels with the self-view of the British Empire at the time. It can also be compared to the William Morris novel, News from Nowhere.

Erewhon satirises various aspects of Victorian society, including criminal punishment, religion and anthropocentrism. For example, according to Erewhonian law, offenders are treated as if they were ill, whereas ill people are looked upon as criminals. Another feature of Erewhon is the absence of machines; this is due to the widely shared perception by the Erewhonians that they are potentially dangerous.

The Book of the Machines[edit]

Butler developed the three chapters of Erewhon that make up "The Book of the Machines" from a number of articles that he had contributed to The Press, which had just begun publication in Christchurch, New Zealand, beginning with "Darwin among the Machines" (1863). Butler was the first to write about the possibility that machines might develop consciousness by natural selection.[4][5]

Many dismissed this as a joke; but, in his preface to the second edition, Butler wrote, "I regret that reviewers have in some cases been inclined to treat the chapters on Machines as an attempt to reduce Mr Darwin's theory to an absurdity. Nothing could be further from my intention, and few things would be more distasteful to me than any attempt to laugh at Mr Darwin."

Characters[edit]

- Higgs—The narrator who informs the reader of the nature of Erewhonian society.

- Chowbok (Kahabuka)—Higgs' guide into the mountains; he is a native who greatly fears the Erewhonians. He eventually abandons Higgs.

- Yram—The daughter of Higgs' jailer who takes care of him when he first enters Erewhon. Her name is Mary spelled backwards.

- Senoj Nosnibor—Higgs' host after he is released from prison; he hopes that Higgs will marry his elder daughter. His name is Robinson Jones backwards.

- Zulora—Senoj Nosnibor's elder daughter—Higgs finds her unpleasant, but her father hopes Higgs will marry her. Her name is Aroluz backwards.

- Arowhena—Senoj Nosnibor's younger daughter; she falls in love with Higgs and runs away with him.

- Mahaina—A woman who claims to suffer from alcoholism but is believed to have a weak temperament.

- Ydgrun—The incomprehensible goddess of the Erewhonians. Her name is an anagram of Grundy (from Mrs. Grundy, a character in Thomas Morton's play Speed the Plough).

Reception[edit]

After its first release, this book sold far better than any of Butler's other works,[clarification needed] perhaps because the British public assumed that the anonymous author was some better-known figure[citation needed] (the favourite being Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who had published The Coming Race two years previously). In a 1945 broadcast, George Orwell praised the book and said that when Butler wrote Erewhon it needed "imagination of a very high order to see that machinery could be dangerous as well as useful." He recommended the novel, though not its sequel, Erewhon Revisited.[6]

Influence and legacy[edit]

Deleuze and Guattari[edit]

The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze used ideas from Butler's book at various points in the development of his philosophy of difference. In Difference and Repetition (1968), Deleuze refers to what he calls "Ideas" as "Erewhon". "Ideas are not concepts", he argues, but rather "a form of eternally positive differential multiplicity, distinguished from the identity of concepts."[7] "Erewhon" refers to the "nomadic distributions" that pertain to simulacra, which "are not universals like the categories, nor are they the hic et nunc or nowhere, the diversity to which categories apply in representation."[8] "Erewhon", in this reading, is "not only a disguised no-where but a rearranged now-here."[9]

In his collaboration with Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus (1972), Deleuze draws on Butler's "The Book of the Machines" to "go beyond" the "usual polemic between vitalism and mechanism" as it relates to their concept of "desiring-machines":[10]

Other uses[edit]

C.S. Lewis alludes to the book in his essay, The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment in the posthumously published collection, God in the Dock (1970).

Aldous Huxley alludes to the book in his novel Island (1962) as does Agatha Christie in Death on the Nile (1937).

In 1994, a group of ex-Yugoslavian writers in Amsterdam, who had established the PEN centre of Yugoslav Writers in Exile, published a single issue of a literary journal Erewhon.[11]

New Zealand sound art organisation, the Audio Foundation, published in 2012 an anthology edited by Bruce Russell named Erewhon Calling after Butler's book.[12]

In 2014, New Zealand artist Gavin Hipkins released his first feature film, titled Erewhon and based on Butler's book. It premiered at the New Zealand International Film Festival and the Edinburgh Art Festival.[13]

In "Smile", the second episode of the 2017 season of Doctor Who, the Doctor and Bill explore a spaceship named Erehwon. Despite the slightly different spelling, the episode writer Frank Cottrell-Boyce confirmed[14] that this was a reference to Butler's novel.

'The Butlerian Jihad' is the name of the crusade to wipeout 'thinking machines' in the novel, Dune, by Frank Herbert.[15]

'Erewhon' is the name of Los Angeles-based natural foods grocery store originally founded in Boston in 1966.[16]

'Erewhon' is also the name of an independent speculative fiction publishing company[17] founded in 2018 by Liz Gorinsky.[18]

See also[edit]

- Rangitata River – the location of the Erewhon sheep station named by Butler who was the first white settler in the area and lived at the Mesopotamia Sheep Station

- Nacirema - another piece of satirical writing with a similar backwards pun

References[edit]

- ^ In the preface to the first edition of his book, Butler specified that "The Author wishes it to be understood that Erewhon is pronounced as a word of three syllables, all short—thus, Ĕ-rĕ-whŏn." Nevertheless, the word is occasionally pronounced with two syllables as "air-hwun" or "air-one".

- ^ Erewhon, or Over the Range (1 ed.). London: Trubner & Co. 1872. Retrieved 5 March 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ George Orwell, Erewhon, BBC Home Service, Talks for Schools, 8 June 1945

- ^ "Darwin among the Machines", reprinted in the Notebooks of Samuel Butler at Project Gutenberg

- ^ Taylor, Tim; Dorin, Alan (2020). Rise of the Self-Replicators: Early Visions of Machines, AI and Robots That Can Reproduce and Evolve. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-48234-3. ISBN 978-3-030-48233-6. S2CID 220855726. Lay summary.

- ^ Orwell, Collected Works, I Belong to the Left, pp. 172–173

- ^ Deleuze (1968, p. 288).

- ^ Deleuze (1968, p. 285).

- ^ Deleuze (1968, p. 333, n.7).

- ^ Deleuze and Guattari (1972, pp. 312–314).

- ^ Erewhon; Blagojevic, Slobodan, et al.

- ^ Hayes, Craig. "Crooked Sounds from Aotearoa 'Erewhon Calling: Experimental Sound in New Zealand". Pop Matters. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Review of 'Erewhon'". CIRCUIT. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "Frank Cottrell-Boyce on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ "The Butlerian Jihad and Darwin among the Machines".

- ^ "History of Erewhon - Natural Foods Pioneer in the United States (1966-2011)" (PDF). Soy Info Center. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ https://www.erewhonbooks.com

- ^ "New Science Fiction and Fantasy Publisher Founded by Former Tor Books Editor". The Hollywood Reporter. 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Mesopotamia Station", Newton, P. (1960)

- "Early Canterbury Runs", Acland, L. G. D. (1946)

- "Samuel Butler of Mesopotamia", Maling, P. B. (1960)

- "The Cradle of Erewhon", Jones, J. (1959)

- “The Day of the Dolphin” (1973 movie starring George C. Scott); it's the name of a motorboat that appears approx. 12 min. into the film.

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |