Bushido - Wikipedia

Bushido

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the Japanese concept of chivalry. For other uses, see Bushido (disambiguation).

-----

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

----

Japanese samurai in armor, 1860s. Photograph by Felice Beato

Bushido (武士道?, "the way (or the moral) of the warrior") is a Japanese term for the samurai way of life, loosely analogous to the concept of chivalry in Europe. Just like the knights of Europe, the samurai had a code to live by that was also based in a moral way of life.

The "way" itself originates from the samurai moral values, most commonly stressing some combination of frugality, loyalty, martial arts mastery, and honor until death. Born from Neo-Confucianism during times of peace in Tokugawa Japan and following Confucian texts, Bushido was also influenced by Shinto and Zen Buddhism, allowing the violent existence of the samurai to be tempered by wisdom and serenity. Bushidō developed between the 16th and 20th centuries, debated by pundits who believed they were building on a legacy dating back to the 10th century, although some scholars have noted that the term bushidō itself is "rarely attested in premodern literature".[1]

Under the Tokugawa Shogunate, some aspects of warrior values became formalized into Japanese feudal law.[2]

The word was first used in Japan during the 17th century in Kōyō Gunkan.[3][4][5] It came into common usage in Japan and the West after the 1899 publication of Nitobe Inazō's Bushido: The Soul of Japan.[6]

In Bushido (1899), Nitobe wrote:

[…] Bushidō, then, is the code of moral principles which the samurai were required or instructed to observe […] More frequently it is a code unuttered and unwritten […] It was an organic growth of decades and centuries of military career. In order to become a samurai this code has to be mastered.

Nitobe was not the first to document Japanese chivalry in this way. In Feudal and Modern Japan (1896), historian Arthur May Knapp wrote: "The samurai of thirty years ago had behind him a thousand years of training in the law of honor, obedience, duty, and self-sacrifice.... It was not needed to create or establish them. As a child he had but to be instructed, as indeed he was from his earliest years, in the etiquette of self-immolation."[7]

Contents [hide]

1 Historical development of Bushido

1.1 Early history to 11th century

1.2 13th to 16th centuries

1.3 17th to 19th centuries

1.4 19th to 21st centuries

2 Tenets

2.1 Eight virtues of Bushidō (as envisioned by Nitobe Inazo)

2.2 Associated virtues

3 Modern translations

4 Major figures associated with Bushidō

4.1 Fictional characters

5 See also

6 References

7 External links and further reading

------

Historical development of Bushido[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Early history to 11th century[edit]

Main article: Bushido literature

Bushidō in Gyo-Kaisho style Kanji. Inscription contains 7 tenets of Bushido.

The Kojiki is Japan's oldest extant book. Written in 721, it contains passages about Yamato Takeru, the son of the Emperor Keikō. It provides an indication of early Japanese military values and literary self-image, including references to the use and admiration of the sword by Japanese warriors.

This early concept is further found in the Shoku Nihongi, an early history of Japan written in 797. The chapter covering the year 721 is notable for an early use of the term "bushi" (武士?) (albeit read as "mononofu" at the time) and a reference to the educated warrior-poet ideal. The Chinese term bushi had entered the Japanese vocabulary with the general introduction of Chinese literature, supplementing the indigenous terms tsuwamono and mononofu. It is also the usage for public placement exams.

An early reference to saburau—a verb meaning to wait upon or to accompany a person of high rank—appears in Kokin Wakashū, the first imperial anthology of poems published in the early 10th century. By the end of the 12th century, saburai ("retainer") had become largely synonymous with bushi, and closely associated with the middle and upper echelons of the warrior class.

Although many of the early literary works of Japan contain the image of the warrior, the term "bushidō" does not appear in early texts like the Kojiki. Warrior ideals and conduct may be illustrated, but the term did not appear in text until the Tokugawa period (1600-1868).[8]

13th to 16th centuries[edit]

From the literature of the 13th to 16th centuries, there exists an abundance of references to military ideals, although none of these should be viewed as early versions of bushido per se. Carl Steenstrup noted that 13th and 14th century writings (gunki monogatari) "portrayed the bushi in their natural element, war, eulogizing such virtues as reckless bravery, fierce family pride, and selfless, at times senseless devotion of master and man".

Compiled over the course of three centuries, beginning in the 1180s, the Heike Monogatari depicts a highly fictionalized and idealized story of a struggle between two warrior clans, the Minamoto and Taira, at the end of the 12th century—a conflict known as the Genpei War. Clearly depicted throughout the Heike Monogatari is the ideal of the cultivated warrior. The warriors in the Heike Monogatari served as models for the educated warriors of later generations, although the ideals depicted by them were assumed to be beyond reach. Nevertheless, during the early modern era, these ideals were vigorously pursued in the upper echelons of warrior society and recommended as the proper form of the Japanese man of arms.

Other examples of the evolution in the Bushidō literature of the 13th to 16th centuries included the Japanese:

Takeda Shingen, by artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi

The Message Of Master Gokurakuji - Hojo Shigetoki (1198–1261)

The Chikubasho - Shiba Yoshimasa (1350–1410)

The Regulations Of Imagawa Ryoshun - Imagawa Sadayo (1325–1420)

The Seventeen Articles Of Asakura Toshikage - Asakura Toshikage (1428–1481)

The Twenty-One Precepts Of Hōjō Sōun - Hojo Nagauji (1432–1519)

The Recorded Words Of Asakura Soteki - Asakura Norikage (1474–1555)

The Iwamizudera Monogatari - Takeda Shingen (1521–1573)

Opinions In Ninety-Nine Articles - Takeda Nobushige (1525–1561)

Lord Nabeshima's Wall Inscriptions - Nabeshima Naoshige (1538–1618)

The Last Statement of Torii Mototada - Torii Mototada (1539–1600)

The Precepts of Kato Kiyomasa - Kato Kiyomasa (1562–1611)

Notes On Regulations - Kuroda Nagamasa (1568–1623)

The sayings of Sengoku-period retainers and warlords such as Kato Kiyomasa and Nabeshima Naoshige were generally recorded or passed down to posterity around the turn of the 16th century when Japan had entered a period of relative peace. In a handbook addressed to "all samurai, regardless of rank", Kato states:

"If a man does not investigate into the matter of Bushido daily, it will be difficult for him to die a brave and manly death. Thus, it is essential to engrave this business of the warrior into one's mind well."

Kato was a ferocious warrior who banned even recitation of poetry, stating:

"One should put forth great effort in matters of learning. One should read books concerning military matters, and direct his attention exclusively to the virtues of loyalty and filial piety....Having been born into the house of a warrior, one's intentions should be to grasp the long and the short swords and to die."[9]

Naoshige says similarly, that it is shameful for any man to die without having risked his life in battle, regardless of rank, and that "Bushidō is in being crazy to die. Fifty or more could not kill one such a man". However, Naoshige also suggests that "everyone should personally know exertion as it is known in the lower classes".[9]

17th to 19th centuries[edit]

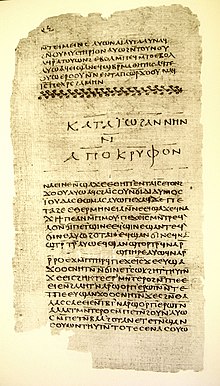

Miyamoto Musashi killing a giant creature, from The Book of Five Rings

Japan enjoyed a period of relative peace during the Tokugawa period from 1600 to the mid-19th century, also called the early modern or the "Edo". During this period, the samurai class played a central role in the policing and administration of the country under the Tokugawa shogunate. The bushidō literature of this time contains much thought relevant to a warrior class seeking more general application of martial principles and experience in peacetime, as well as reflection on the land's long history of war. The literature of this time includes:

The Last Statement of Torii Mototada (1539–1600)

Kuroda Nagamasa (1568–1623)

Nabeshima Naoshige (1538–1618)

Budo Shoshinshu (武道初心集) by Taira Shigesuke, Daidōji Yūzan (1639–1730)

Hagakure as related by Yamamoto Tsunetomo to Tsuramoto Tashiro.

Bugei Juhappan (武芸十八般)

A Book of Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi

The Hagakure contains many sayings attributed to Sengoku-period retainer Nabeshima Naoshige (1537–1619) regarding Bushidō related philosophy early in the 18th century by Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659–1719), a former retainer to Naoshige's grandson, Nabeshima Mitsushige. The Hagakure was compiled in the early 18th century, but was kept as a kind of "secret teaching" of the Nabeshima clan until was the end of the Tokugawa era (1867).[10] His saying, "I have found the way of the warrior is death", was a summation of the focus on honor and reputation over all else that bushido codified.[11]

Tokugawa-era rōnin scholar and strategist Yamaga Sokō (1622–1685) wrote extensively on matters relating to bushidō, bukyō (a "warrior's creed"), and a more general shido, a "way of gentlemen" intended for application to all stations of society. Sokō attempts to codify a kind of "universal bushidō" with a special emphasis on "pure" Confucian values, (rejecting the mystical influences of Tao and Buddhism in Neo-Confucian orthodoxy), while at the same time calling for recognition of the singular and divine nature of Japan and Japanese culture. These radical concepts—including ultimate devotion to the Emperor, regardless of rank or clan—put him at odds with the reigning shogunate. He was exiled to the Akō domain, (the future setting of the 47 Rōnin incident), and his works were not widely read until the rise of nationalism in the early 20th century.

The aging Tsunetomo's interpretation of bushidō is perhaps more illustrative of the philosophy refined by his unique station and experience, at once dutiful and defiant, ultimately incompatible with the mores and laws of an emerging civil society. Of the 47, Rōnin—to this day, generally regarded as exemplars of bushido—Tsunetomo felt they were remiss in hatching such a wily, delayed plot for revenge, and had been over-concerned with the success of their undertaking. Instead, Tsunetomo felt true samurai should act without hesitation to fulfill their duties, without regard for success or failure.

This romantic sentiment is of course expressed by warriors down through history, though it may run counter to the art of war itself. This ambivalence is found in the heart of bushidō, and perhaps all such "warrior codes". Some combination of traditional bushidō's organic contradictions and more "universal" or "progressive" formulations (like those of Yamaga Soko) would inform Japan's disastrous military ambitions in the 20th century.

19th to 21st centuries[edit]

Recent scholarship in both Japan and abroad has focused on differences between the samurai class and the bushidō theories that developed in modern Japan. Bushidō in the prewar period was often emperor-centered and placed much greater value on the virtues of loyalty and self-sacrifice than did many Tokugawa-era interpretations.[12] Bushidō was used as a propaganda tool by the government and military, who doctored it to suit their needs.[13] Scholars of Japanese history agree that the bushidō that spread throughout modern Japan was not simply a continuation of earlier traditions.

More recently, it has been argued that modern bushidō discourse originated in the 1880s as a response to foreign stimuli, such as the English concept of "gentlemanship", by Japanese with considerable exposure to Western culture. Nitobe Inazo's bushidō interpretations followed a similar trajectory, although he was following earlier trends. This relatively pacifistic bushidō was then hijacked and adapted by militarists and the government from the early 1900s onward as nationalism increased around the time of the Russo-Japanese War.[14]

The junshi suicide of General Nogi Maresuke and his wife on the death of Emperor Meiji occasioned both praise, as an example to the decaying morals of Japan, and criticism, explicitly declaring that the spirit of bushido thus exemplified should not be revived.[15]

During pre-World War II and World War II Shōwa Japan, bushido was pressed into use for militarism,[16] to present war as purifying, and death a duty.[17] This was presented as revitalizing traditional values and "transcending the modern".[18] Bushido would provide a spiritual shield to let soldiers fight to the end.[19] As the war turned, the spirit of bushido was invoked to urge that all depended on the firm and united soul of the nation.[20] When the Battle of Attu was lost, attempts were made to make the more than two thousand Japanese deaths an inspirational epic for the fighting spirit of the nation.[21] Arguments that the plans for the Battle of Leyte Gulf, involving all Japanese ships, would expose Japan to serious danger if they failed, were countered with the plea that the Navy be permitted to "bloom as flowers of death".[22] The first proposals of organized suicide attacks met resistance because while bushido called for a warrior to be always aware of death, but not to view it as the sole end, but the desperate straits brought about acceptance.[23] Such attacks were acclaimed as the true spirit of bushido.[24]

Denials of mistreatment of prisoners of war declared that they were being well-treated by virtue of bushido generosity.[25] Broadcast interviews with prisoners were also described as being not propaganda but out of sympathy with the enemy, such sympathy as only bushido could inspire.[26]

The famous writer Yukio Mishima was outspoken in his by-then anachronistic commitment to bushido in the 1960s, until his ritual suicide by seppuku after a failed coup d'état in November 1970.

Tenets[edit]

Bushidō expanded and formalized the earlier code of the samurai, and stressed frugality, loyalty, mastery of martial arts, and honor to the death. Under the bushidō ideal, if a samurai failed to uphold his honor he could only regain it by performing seppuku (ritual suicide).

In an excerpt from his book Samurai: The World of the Warrior,[27] historian Stephen Turnbull describes the role of seppuku in feudal Japan:

In the world of the warrior, seppuku was a deed of bravery that was admirable in a samurai who knew he was defeated, disgraced, or mortally wounded. It meant that he could end his days with his transgressions wiped away and with his reputation not merely intact but actually enhanced. The cutting of the abdomen released the samurai’s spirit in the most dramatic fashion, but it was an extremely painful and unpleasant way to die, and sometimes the samurai who was performing the act asked a loyal comrade to cut off his head at the moment of agony.

Bushidō varied dramatically over time, and across the geographic and socio-economic backgrounds of the samurai, who represented somewhere between 5% and 10% of the Japanese population.[28] The first Meiji-era census at the end of the 19th century counted 1,282,000 members of the "high samurai", allowed to ride a horse, and 492,000 members of the "low samurai", allowed to wear two swords but not to ride a horse, in a country of about 25 million.[29]

Some versions of Bushidō include compassion for those of lower station, and for the preservation of one's name.[9] Early bushidō literature further enforces the requirement to conduct oneself with calmness, fairness, justice, and propriety.[9] The relationship between learning and the way of the warrior is clearly articulated, one being a natural partner to the other.[9]

Other pundits pontificating on the warrior philosophy covered methods of raising children, appearance, and grooming, but all of this may be seen as part of one's constant preparation for death—to die a good death with one's honor intact, the ultimate aim in a life lived according to bushidō. Indeed, a "good death" is its own reward, and by no means assurance of "future rewards" in the afterlife. Some samurai, though certainly not all (e.g., Amakusa Shiro), have throughout history held such aims or beliefs in disdain, or expressed the awareness that their station—as it involves killing—precludes such reward, especially in Buddhism. Japanese beliefs surrounding the Samurai and the afterlife are complex and often contradictory, while the soul of a noble warrior suffering in hell or as a lingering spirit occasionally appears in Japanese art and literature, so does the idea of a warrior being reborn upon a lotus throne in paradise[30]

Eight virtues of Bushidō (as envisioned by Nitobe Inazo)[edit]

[31] The Bushidō code is typified by eight virtues:

Righteousness, Integrity (義 gi?)

Be acutely honest throughout your dealings with all people. Believe in justice, not from other people, but from yourself. To the true warrior, all points of view are deeply considered regarding honestly, justice and integrity. Warriors make a full commitment to their decisions.

Heroic Courage (勇 yū?)

Hiding like a turtle in a shell is not living at all. A true warrior must have heroic courage. It is absolutely risky. It is living life completely, fully and wonderfully. Heroic courage is not blind. It is intelligent and strong.

Benevolence, Compassion (仁 jin?)

Through intense training and hard work the true warrior becomes quick and strong. They are not as most people. They develop a power that must be used for good. They have compassion. They help their fellow man at every opportunity. If an opportunity does not arise, they go out of their way to find one.

Respect (礼 rei?)

True warriors have no reason to be cruel. They do not need to prove their strength. Warriors are not only respected for their strength in battle, but also by their dealings with others. The true strength of a warrior becomes apparent during difficult times.

Honesty and Sincerity (誠 makoto?)

When warriors say that they will perform an action, it is as good as done. Nothing will stop them from completing what they say they will do. They do not have to 'give their word'. They do not have to 'promise'. Speaking and doing are the same action.

Honour (名誉 meiyo?)

Warriors have only one judge of honor and character, and this is themselves. Decisions they make and how these decisions are carried out is a reflection of whom they truly are. You cannot hide from yourself.

Duty and Loyalty (忠義 chūgi?)

Warriors are responsible for everything that they have done and everything that they have said, and all of the consequences that follow. They are immensely loyal to all of those in their care. To everyone that they are responsible for, they remain fiercely true.

Self-Control (自制 jisei?)

Associated virtues[edit]

Filial piety (孝 kō?)

Wisdom (智 chi?)

Fraternal Respect (悌 tei?)

-----

Modern translations[edit]

Modern Western translation of documents related to Bushidō began in the 1970s with Carl Steenstrup, who performed research into the ethical codes of famous Samurai clans including Hōjō Sōun and Imagawa Sadayo.[32]

Primary research into Bushidō was later conducted by William Scott Wilson in his 1982 text Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors. The writings span hundreds of years, family lineage, geography, social class and writing style—yet share a common set of values. Wilson's work also examined the earliest Japanese writings in the 8th century: the Kojiki, Shoku Nihongi, the Kokin Wakashū, Konjaku Monogatari, and the Heike Monogatari, as well as the Chinese Classics (the Analects, the Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, and the Mencius).

In May 2008, Thomas Cleary translated a collection of 22 writings on Bushido by warriors, scholars, political advisers, and educators, spanning 500 years from the 14th to the 19th centuries. Titled Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook, it gave an insider's view of the samurai world: "the moral and psychological development of the warrior, the ethical standards they were meant to uphold, their training in both martial arts and strategy, and the enormous role that the traditions of Shintoism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism had in influencing samurai ideals".

----

Major figures associated with Bushidō[edit]

Asano Naganori

Imagawa Ryōshun

Katō Kiyomasa

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

Tadakatsu Honda

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Torii Mototada

Sasaki Kojirō

Saigō Takamori

Yamaga Sokō

Yamamoto Tsunetomo

Yamaoka Tesshū

Yukio Mishima

Hijikata Toshizō

Miyamoto Musashi

----

Fictional characters[edit]

Spike Spiegel

Ogami Ittō

Samurai Jack

Roronoa Zoro

Auron

Cyan Garamonde

Miyamoto Usagi

Kenshin Himura

Jubei Yagyu

---

See also[edit]

Budō

Hagakure

Hana wa sakuragi, hito wa bushi

Shudō

Japanese martial arts

The Unfettered Mind

Zen

Zen at War

---

References[edit]

Jump up ^ "The Zen of Japanese Nationalism", by Robert H. Shart, in Curators of the Buddha, edited by Donald Lopez, p. 111

Jump up ^ Japanese Feudal Laws John Carey Hall, The Tokugawa Legislation (Yokohama, 1910), pp. 286-319 Archived October 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

Jump up ^ Willcock, Hiroko (2008). The Japanese Political Thought of Uchimura Kanzō (1861-1930): Synthesizing Bushidō, Christianity, Nationalism, and Liberalism. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 077345151X. Koyo gunkan is the earliest comprehensive extant work that provides a notion of Bushido as a samurai ethos and the value system of the samurai tradition.

Jump up ^ Ikegami, Eiko, The Taming of the Samurai, Harvard University Press, 1995. p. 278

Jump up ^ Kasaya, Kazuhiko (2014). 武士道 第一章 武士道という語の登場 [Bushido Chapter I Appearance of the word Bushido] (in Japanese). NTT publishing. p. 7. ISBN 4757143222.

Jump up ^ Friday, Karl F. "Bushidō or Bull? A Medieval Historian's Perspective on the Imperial Army and the Japanese Warrior Tradition" The History Teacher, Vol. 27, No. 3 (May, 1994), pp. 340

Jump up ^ Arthur May Knapp (1896). "Feudal and Modern Japan". Retrieved 2010-01-02.[dead link]

Jump up ^ "The Zen of Japanese Nationalism," by Robert H. Sharf, in Curators of the Buddha, edited by Donald Lopez, p. 111

^ Jump up to: a b c d e William Scott Wilson, Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors (Kodansha, 1982) ISBN 0-89750-081-4

Jump up ^ "The Samurai Series: The Book of Five Rings, Hagakure -The Way of the Samurai & Bushido - The Soul of Japan" ELPN Press (November, 2006) ISBN 1-934255-01-7

Jump up ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 7 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

Jump up ^ Eiko Ikegami. The Taming of the Samurai: Honorific Individualism and the Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Jump up ^ Karl Friday. Bushidō or Bull? A Medieval Historian's Perspective on the Imperial Army and the Japanese Warrior Tradition. The History Teacher, Volume 27, Number 3, May 1994, pages 339-349.[1]

Jump up ^ Oleg Benesch. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 0198706626, ISBN 9780198706625

Jump up ^ Herbert P. Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan p 42-3 ISBN 0-06-019314-X

Jump up ^ "No Surrender: Background History"

Jump up ^ David Powers, "Japan: No Surrender in World War Two"

Jump up ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p1 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

Jump up ^ Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won p 6 ISBN 0-393-03925-0

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 334 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 444 Random House New York 1970

Jump up ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 539 Random House New York 1970

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 356 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 360 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 256 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 257 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ excerpt from Samurai: The World of the Warrior by Stephen Turnbull

Jump up ^ Cleary, Thomas Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook Shambhala (May, 2008) ISBN 1-59030-572-8

Jump up ^ Mikiso Hane Modern Japan: A Historical Survey, Third Edition Westview Press (January, 2001) ISBN 0-8133-3756-9

Jump up ^ Zeami Motokiyo "Atsumori"

Jump up ^ Bushido: The Soul of Japan

Jump up ^ Monumenta Nipponica

External links and further reading[edit]

Oleg Benesch. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 0198706626, ISBN 9780198706625

易經道 Yijing Dao, 鳴鶴在陰 Calling crane in the shade, Biroco - The Art of Doing Nothing, 2002-2012, 馬夏 Ma, Xia, et. al., [2]

"Bushido Arcade" a Contemporary translation of the Bushido [3]

William Scott Wilson, Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors (Kodansha, 1982) ISBN 0-89750-081-4

Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook by Thomas Cleary 288 pages Shambhala (May 13, 2008) ISBN 1-59030-572-8 ISBN 978-1590305720

Katsumata Shizuo with Martin Collcutt, "The Development of Sengoku Law," in Hall, Nagahara, and Yamamura (eds.), Japan Before Tokugawa: Political Consolidation and Economic Growth (1981), chapter 3.

K. A. Grossberg & N. Kanamoto 1981, The Laws of the Muromachi Bakufu: Kemmu Shikimoku (1336) and Muromachi Bakufu Tsuikaho, MN Monographs (Sophia UP)

Hall, John C. "Japanese Feudal Laws: the Magisterial Code of the Hojo Power Holders (1232) ." Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 2nd ser. 34 (1906)

"Japanese Feudal laws: The Ashikaga Code." Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 1st ser. 36 (1908):

John Allyn, "Forty-Seven Ronin Story" ISBN 0-8048-0196-7

Imagawa Ryoshun, The Regulations of Imagawa Ryoshun (1412 A.D.) Imagawa_Ryoshun

Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford, 1st Baron Redesdale, Final_Statement_of_the_47_Ronin (1701 A.D.)

The Message Of Master Gokurakuji — Hōjō Shigetoki (1198A.D.-1261A.D.) Hojo_shigetoki

Sunset of the Samurai--The True Story of Saigo Takamori Military History Magazine

Onoda, Hiroo, No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War. Trans. Charles S. Terry. (New York, Kodansha International Ltd, 1974) ISBN 1-55750-663-9

An interview with William Scott Wilson about Bushidō

Bushidō Website: a good definition of bushidō, including The Samurai Creed

The website of William Scott Wilson A 2005 recipient of the Japanese Government's Japan’s Foreign Minister’s Commendation, William Scott Wilson was honored for his research on Samurai and Bushidō.

Hojo Shigetoki (1198-1261)and His Role in the History of Political and Ethical Ideas in Japan by Carl Steenstrup; Curzon Press (1979)ISBN 0-7007-0132-X

A History of Law in Japan Until 1868 by Carl Steenstrup; Brill Academic Publishers;second edition (1996) ISBN 90-04-10453-4

Bushido — The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe (1905) (ISBN 0-8048-3413-X)

Budoshoshinshu - The Code of The Warrior by Daidōji Yūzan (ISBN 0-89750-096-2)

Hagakure-The Book of the Samurai By Tsunetomo Yamamoto (ISBN 4-7700-1106-7 paperback, ISBN 4-7700-2916-0 hardcover)

Go Rin No Sho - Miyamoto Musashi (1645) (ISBN 4-7700-2801-6 hardback, ISBN 4-7700-2844-X hardback Japan only)

The Unfettered Mind - Writings of the Zen Master to the Sword master by Takuan Sōhō (Musashi's mentor) (ISBN 0-87011-851-X)

The Religion of the Samurai (1913 original text), by Kaiten Nukariya, 2007 reprint by ELPN Press ISBN 0-9773400-7-4

Tales of Old Japan by Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford (1871) reprinted 1910

Sakujiro Yokoyama's Account of a Samurai Sword Duel

Death Before Dishonor By Masaru Fujimoto — Special to The Japan Times: Dec. 15, 2002

Osprey, "Elite and Warrior Series" Assorted. [4]

Stephen Turnbull, "Samurai Warfare" (London, 1996), Cassell & Co ISBN 1-85409-280-4

Lee Teng-hui, former President of the Republic of China, "武士道解題 做人的根本 蕭志強譯" in Chinese,前衛, "「武士道」解題―ノーブレス・オブリージュとは" in Japanese,小学館,(2003), ISBN 4-09-387370-4

Bushido

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the Japanese concept of chivalry. For other uses, see Bushido (disambiguation).

-----

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

----

Japanese samurai in armor, 1860s. Photograph by Felice Beato

Bushido (武士道?, "the way (or the moral) of the warrior") is a Japanese term for the samurai way of life, loosely analogous to the concept of chivalry in Europe. Just like the knights of Europe, the samurai had a code to live by that was also based in a moral way of life.

The "way" itself originates from the samurai moral values, most commonly stressing some combination of frugality, loyalty, martial arts mastery, and honor until death. Born from Neo-Confucianism during times of peace in Tokugawa Japan and following Confucian texts, Bushido was also influenced by Shinto and Zen Buddhism, allowing the violent existence of the samurai to be tempered by wisdom and serenity. Bushidō developed between the 16th and 20th centuries, debated by pundits who believed they were building on a legacy dating back to the 10th century, although some scholars have noted that the term bushidō itself is "rarely attested in premodern literature".[1]

Under the Tokugawa Shogunate, some aspects of warrior values became formalized into Japanese feudal law.[2]

The word was first used in Japan during the 17th century in Kōyō Gunkan.[3][4][5] It came into common usage in Japan and the West after the 1899 publication of Nitobe Inazō's Bushido: The Soul of Japan.[6]

In Bushido (1899), Nitobe wrote:

[…] Bushidō, then, is the code of moral principles which the samurai were required or instructed to observe […] More frequently it is a code unuttered and unwritten […] It was an organic growth of decades and centuries of military career. In order to become a samurai this code has to be mastered.

Nitobe was not the first to document Japanese chivalry in this way. In Feudal and Modern Japan (1896), historian Arthur May Knapp wrote: "The samurai of thirty years ago had behind him a thousand years of training in the law of honor, obedience, duty, and self-sacrifice.... It was not needed to create or establish them. As a child he had but to be instructed, as indeed he was from his earliest years, in the etiquette of self-immolation."[7]

Contents [hide]

1 Historical development of Bushido

1.1 Early history to 11th century

1.2 13th to 16th centuries

1.3 17th to 19th centuries

1.4 19th to 21st centuries

2 Tenets

2.1 Eight virtues of Bushidō (as envisioned by Nitobe Inazo)

2.2 Associated virtues

3 Modern translations

4 Major figures associated with Bushidō

4.1 Fictional characters

5 See also

6 References

7 External links and further reading

------

Historical development of Bushido[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Early history to 11th century[edit]

Main article: Bushido literature

Bushidō in Gyo-Kaisho style Kanji. Inscription contains 7 tenets of Bushido.

The Kojiki is Japan's oldest extant book. Written in 721, it contains passages about Yamato Takeru, the son of the Emperor Keikō. It provides an indication of early Japanese military values and literary self-image, including references to the use and admiration of the sword by Japanese warriors.

This early concept is further found in the Shoku Nihongi, an early history of Japan written in 797. The chapter covering the year 721 is notable for an early use of the term "bushi" (武士?) (albeit read as "mononofu" at the time) and a reference to the educated warrior-poet ideal. The Chinese term bushi had entered the Japanese vocabulary with the general introduction of Chinese literature, supplementing the indigenous terms tsuwamono and mononofu. It is also the usage for public placement exams.

An early reference to saburau—a verb meaning to wait upon or to accompany a person of high rank—appears in Kokin Wakashū, the first imperial anthology of poems published in the early 10th century. By the end of the 12th century, saburai ("retainer") had become largely synonymous with bushi, and closely associated with the middle and upper echelons of the warrior class.

Although many of the early literary works of Japan contain the image of the warrior, the term "bushidō" does not appear in early texts like the Kojiki. Warrior ideals and conduct may be illustrated, but the term did not appear in text until the Tokugawa period (1600-1868).[8]

13th to 16th centuries[edit]

From the literature of the 13th to 16th centuries, there exists an abundance of references to military ideals, although none of these should be viewed as early versions of bushido per se. Carl Steenstrup noted that 13th and 14th century writings (gunki monogatari) "portrayed the bushi in their natural element, war, eulogizing such virtues as reckless bravery, fierce family pride, and selfless, at times senseless devotion of master and man".

Compiled over the course of three centuries, beginning in the 1180s, the Heike Monogatari depicts a highly fictionalized and idealized story of a struggle between two warrior clans, the Minamoto and Taira, at the end of the 12th century—a conflict known as the Genpei War. Clearly depicted throughout the Heike Monogatari is the ideal of the cultivated warrior. The warriors in the Heike Monogatari served as models for the educated warriors of later generations, although the ideals depicted by them were assumed to be beyond reach. Nevertheless, during the early modern era, these ideals were vigorously pursued in the upper echelons of warrior society and recommended as the proper form of the Japanese man of arms.

Other examples of the evolution in the Bushidō literature of the 13th to 16th centuries included the Japanese:

Takeda Shingen, by artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi

The Message Of Master Gokurakuji - Hojo Shigetoki (1198–1261)

The Chikubasho - Shiba Yoshimasa (1350–1410)

The Regulations Of Imagawa Ryoshun - Imagawa Sadayo (1325–1420)

The Seventeen Articles Of Asakura Toshikage - Asakura Toshikage (1428–1481)

The Twenty-One Precepts Of Hōjō Sōun - Hojo Nagauji (1432–1519)

The Recorded Words Of Asakura Soteki - Asakura Norikage (1474–1555)

The Iwamizudera Monogatari - Takeda Shingen (1521–1573)

Opinions In Ninety-Nine Articles - Takeda Nobushige (1525–1561)

Lord Nabeshima's Wall Inscriptions - Nabeshima Naoshige (1538–1618)

The Last Statement of Torii Mototada - Torii Mototada (1539–1600)

The Precepts of Kato Kiyomasa - Kato Kiyomasa (1562–1611)

Notes On Regulations - Kuroda Nagamasa (1568–1623)

The sayings of Sengoku-period retainers and warlords such as Kato Kiyomasa and Nabeshima Naoshige were generally recorded or passed down to posterity around the turn of the 16th century when Japan had entered a period of relative peace. In a handbook addressed to "all samurai, regardless of rank", Kato states:

"If a man does not investigate into the matter of Bushido daily, it will be difficult for him to die a brave and manly death. Thus, it is essential to engrave this business of the warrior into one's mind well."

Kato was a ferocious warrior who banned even recitation of poetry, stating:

"One should put forth great effort in matters of learning. One should read books concerning military matters, and direct his attention exclusively to the virtues of loyalty and filial piety....Having been born into the house of a warrior, one's intentions should be to grasp the long and the short swords and to die."[9]

Naoshige says similarly, that it is shameful for any man to die without having risked his life in battle, regardless of rank, and that "Bushidō is in being crazy to die. Fifty or more could not kill one such a man". However, Naoshige also suggests that "everyone should personally know exertion as it is known in the lower classes".[9]

17th to 19th centuries[edit]

Miyamoto Musashi killing a giant creature, from The Book of Five Rings

Japan enjoyed a period of relative peace during the Tokugawa period from 1600 to the mid-19th century, also called the early modern or the "Edo". During this period, the samurai class played a central role in the policing and administration of the country under the Tokugawa shogunate. The bushidō literature of this time contains much thought relevant to a warrior class seeking more general application of martial principles and experience in peacetime, as well as reflection on the land's long history of war. The literature of this time includes:

The Last Statement of Torii Mototada (1539–1600)

Kuroda Nagamasa (1568–1623)

Nabeshima Naoshige (1538–1618)

Budo Shoshinshu (武道初心集) by Taira Shigesuke, Daidōji Yūzan (1639–1730)

Hagakure as related by Yamamoto Tsunetomo to Tsuramoto Tashiro.

Bugei Juhappan (武芸十八般)

A Book of Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi

The Hagakure contains many sayings attributed to Sengoku-period retainer Nabeshima Naoshige (1537–1619) regarding Bushidō related philosophy early in the 18th century by Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659–1719), a former retainer to Naoshige's grandson, Nabeshima Mitsushige. The Hagakure was compiled in the early 18th century, but was kept as a kind of "secret teaching" of the Nabeshima clan until was the end of the Tokugawa era (1867).[10] His saying, "I have found the way of the warrior is death", was a summation of the focus on honor and reputation over all else that bushido codified.[11]

Tokugawa-era rōnin scholar and strategist Yamaga Sokō (1622–1685) wrote extensively on matters relating to bushidō, bukyō (a "warrior's creed"), and a more general shido, a "way of gentlemen" intended for application to all stations of society. Sokō attempts to codify a kind of "universal bushidō" with a special emphasis on "pure" Confucian values, (rejecting the mystical influences of Tao and Buddhism in Neo-Confucian orthodoxy), while at the same time calling for recognition of the singular and divine nature of Japan and Japanese culture. These radical concepts—including ultimate devotion to the Emperor, regardless of rank or clan—put him at odds with the reigning shogunate. He was exiled to the Akō domain, (the future setting of the 47 Rōnin incident), and his works were not widely read until the rise of nationalism in the early 20th century.

The aging Tsunetomo's interpretation of bushidō is perhaps more illustrative of the philosophy refined by his unique station and experience, at once dutiful and defiant, ultimately incompatible with the mores and laws of an emerging civil society. Of the 47, Rōnin—to this day, generally regarded as exemplars of bushido—Tsunetomo felt they were remiss in hatching such a wily, delayed plot for revenge, and had been over-concerned with the success of their undertaking. Instead, Tsunetomo felt true samurai should act without hesitation to fulfill their duties, without regard for success or failure.

This romantic sentiment is of course expressed by warriors down through history, though it may run counter to the art of war itself. This ambivalence is found in the heart of bushidō, and perhaps all such "warrior codes". Some combination of traditional bushidō's organic contradictions and more "universal" or "progressive" formulations (like those of Yamaga Soko) would inform Japan's disastrous military ambitions in the 20th century.

19th to 21st centuries[edit]

Recent scholarship in both Japan and abroad has focused on differences between the samurai class and the bushidō theories that developed in modern Japan. Bushidō in the prewar period was often emperor-centered and placed much greater value on the virtues of loyalty and self-sacrifice than did many Tokugawa-era interpretations.[12] Bushidō was used as a propaganda tool by the government and military, who doctored it to suit their needs.[13] Scholars of Japanese history agree that the bushidō that spread throughout modern Japan was not simply a continuation of earlier traditions.

More recently, it has been argued that modern bushidō discourse originated in the 1880s as a response to foreign stimuli, such as the English concept of "gentlemanship", by Japanese with considerable exposure to Western culture. Nitobe Inazo's bushidō interpretations followed a similar trajectory, although he was following earlier trends. This relatively pacifistic bushidō was then hijacked and adapted by militarists and the government from the early 1900s onward as nationalism increased around the time of the Russo-Japanese War.[14]

The junshi suicide of General Nogi Maresuke and his wife on the death of Emperor Meiji occasioned both praise, as an example to the decaying morals of Japan, and criticism, explicitly declaring that the spirit of bushido thus exemplified should not be revived.[15]

During pre-World War II and World War II Shōwa Japan, bushido was pressed into use for militarism,[16] to present war as purifying, and death a duty.[17] This was presented as revitalizing traditional values and "transcending the modern".[18] Bushido would provide a spiritual shield to let soldiers fight to the end.[19] As the war turned, the spirit of bushido was invoked to urge that all depended on the firm and united soul of the nation.[20] When the Battle of Attu was lost, attempts were made to make the more than two thousand Japanese deaths an inspirational epic for the fighting spirit of the nation.[21] Arguments that the plans for the Battle of Leyte Gulf, involving all Japanese ships, would expose Japan to serious danger if they failed, were countered with the plea that the Navy be permitted to "bloom as flowers of death".[22] The first proposals of organized suicide attacks met resistance because while bushido called for a warrior to be always aware of death, but not to view it as the sole end, but the desperate straits brought about acceptance.[23] Such attacks were acclaimed as the true spirit of bushido.[24]

Denials of mistreatment of prisoners of war declared that they were being well-treated by virtue of bushido generosity.[25] Broadcast interviews with prisoners were also described as being not propaganda but out of sympathy with the enemy, such sympathy as only bushido could inspire.[26]

The famous writer Yukio Mishima was outspoken in his by-then anachronistic commitment to bushido in the 1960s, until his ritual suicide by seppuku after a failed coup d'état in November 1970.

Tenets[edit]

Bushidō expanded and formalized the earlier code of the samurai, and stressed frugality, loyalty, mastery of martial arts, and honor to the death. Under the bushidō ideal, if a samurai failed to uphold his honor he could only regain it by performing seppuku (ritual suicide).

In an excerpt from his book Samurai: The World of the Warrior,[27] historian Stephen Turnbull describes the role of seppuku in feudal Japan:

In the world of the warrior, seppuku was a deed of bravery that was admirable in a samurai who knew he was defeated, disgraced, or mortally wounded. It meant that he could end his days with his transgressions wiped away and with his reputation not merely intact but actually enhanced. The cutting of the abdomen released the samurai’s spirit in the most dramatic fashion, but it was an extremely painful and unpleasant way to die, and sometimes the samurai who was performing the act asked a loyal comrade to cut off his head at the moment of agony.

Bushidō varied dramatically over time, and across the geographic and socio-economic backgrounds of the samurai, who represented somewhere between 5% and 10% of the Japanese population.[28] The first Meiji-era census at the end of the 19th century counted 1,282,000 members of the "high samurai", allowed to ride a horse, and 492,000 members of the "low samurai", allowed to wear two swords but not to ride a horse, in a country of about 25 million.[29]

Some versions of Bushidō include compassion for those of lower station, and for the preservation of one's name.[9] Early bushidō literature further enforces the requirement to conduct oneself with calmness, fairness, justice, and propriety.[9] The relationship between learning and the way of the warrior is clearly articulated, one being a natural partner to the other.[9]

Other pundits pontificating on the warrior philosophy covered methods of raising children, appearance, and grooming, but all of this may be seen as part of one's constant preparation for death—to die a good death with one's honor intact, the ultimate aim in a life lived according to bushidō. Indeed, a "good death" is its own reward, and by no means assurance of "future rewards" in the afterlife. Some samurai, though certainly not all (e.g., Amakusa Shiro), have throughout history held such aims or beliefs in disdain, or expressed the awareness that their station—as it involves killing—precludes such reward, especially in Buddhism. Japanese beliefs surrounding the Samurai and the afterlife are complex and often contradictory, while the soul of a noble warrior suffering in hell or as a lingering spirit occasionally appears in Japanese art and literature, so does the idea of a warrior being reborn upon a lotus throne in paradise[30]

Eight virtues of Bushidō (as envisioned by Nitobe Inazo)[edit]

[31] The Bushidō code is typified by eight virtues:

Righteousness, Integrity (義 gi?)

Be acutely honest throughout your dealings with all people. Believe in justice, not from other people, but from yourself. To the true warrior, all points of view are deeply considered regarding honestly, justice and integrity. Warriors make a full commitment to their decisions.

Heroic Courage (勇 yū?)

Hiding like a turtle in a shell is not living at all. A true warrior must have heroic courage. It is absolutely risky. It is living life completely, fully and wonderfully. Heroic courage is not blind. It is intelligent and strong.

Benevolence, Compassion (仁 jin?)

Through intense training and hard work the true warrior becomes quick and strong. They are not as most people. They develop a power that must be used for good. They have compassion. They help their fellow man at every opportunity. If an opportunity does not arise, they go out of their way to find one.

Respect (礼 rei?)

True warriors have no reason to be cruel. They do not need to prove their strength. Warriors are not only respected for their strength in battle, but also by their dealings with others. The true strength of a warrior becomes apparent during difficult times.

Honesty and Sincerity (誠 makoto?)

When warriors say that they will perform an action, it is as good as done. Nothing will stop them from completing what they say they will do. They do not have to 'give their word'. They do not have to 'promise'. Speaking and doing are the same action.

Honour (名誉 meiyo?)

Warriors have only one judge of honor and character, and this is themselves. Decisions they make and how these decisions are carried out is a reflection of whom they truly are. You cannot hide from yourself.

Duty and Loyalty (忠義 chūgi?)

Warriors are responsible for everything that they have done and everything that they have said, and all of the consequences that follow. They are immensely loyal to all of those in their care. To everyone that they are responsible for, they remain fiercely true.

Self-Control (自制 jisei?)

Associated virtues[edit]

Filial piety (孝 kō?)

Wisdom (智 chi?)

Fraternal Respect (悌 tei?)

-----

Modern translations[edit]

Modern Western translation of documents related to Bushidō began in the 1970s with Carl Steenstrup, who performed research into the ethical codes of famous Samurai clans including Hōjō Sōun and Imagawa Sadayo.[32]

Primary research into Bushidō was later conducted by William Scott Wilson in his 1982 text Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors. The writings span hundreds of years, family lineage, geography, social class and writing style—yet share a common set of values. Wilson's work also examined the earliest Japanese writings in the 8th century: the Kojiki, Shoku Nihongi, the Kokin Wakashū, Konjaku Monogatari, and the Heike Monogatari, as well as the Chinese Classics (the Analects, the Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, and the Mencius).

In May 2008, Thomas Cleary translated a collection of 22 writings on Bushido by warriors, scholars, political advisers, and educators, spanning 500 years from the 14th to the 19th centuries. Titled Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook, it gave an insider's view of the samurai world: "the moral and psychological development of the warrior, the ethical standards they were meant to uphold, their training in both martial arts and strategy, and the enormous role that the traditions of Shintoism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism had in influencing samurai ideals".

----

Major figures associated with Bushidō[edit]

Asano Naganori

Imagawa Ryōshun

Katō Kiyomasa

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

Tadakatsu Honda

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Torii Mototada

Sasaki Kojirō

Saigō Takamori

Yamaga Sokō

Yamamoto Tsunetomo

Yamaoka Tesshū

Yukio Mishima

Hijikata Toshizō

Miyamoto Musashi

----

Fictional characters[edit]

Spike Spiegel

Ogami Ittō

Samurai Jack

Roronoa Zoro

Auron

Cyan Garamonde

Miyamoto Usagi

Kenshin Himura

Jubei Yagyu

---

See also[edit]

Budō

Hagakure

Hana wa sakuragi, hito wa bushi

Shudō

Japanese martial arts

The Unfettered Mind

Zen

Zen at War

---

References[edit]

Jump up ^ "The Zen of Japanese Nationalism", by Robert H. Shart, in Curators of the Buddha, edited by Donald Lopez, p. 111

Jump up ^ Japanese Feudal Laws John Carey Hall, The Tokugawa Legislation (Yokohama, 1910), pp. 286-319 Archived October 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

Jump up ^ Willcock, Hiroko (2008). The Japanese Political Thought of Uchimura Kanzō (1861-1930): Synthesizing Bushidō, Christianity, Nationalism, and Liberalism. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 077345151X. Koyo gunkan is the earliest comprehensive extant work that provides a notion of Bushido as a samurai ethos and the value system of the samurai tradition.

Jump up ^ Ikegami, Eiko, The Taming of the Samurai, Harvard University Press, 1995. p. 278

Jump up ^ Kasaya, Kazuhiko (2014). 武士道 第一章 武士道という語の登場 [Bushido Chapter I Appearance of the word Bushido] (in Japanese). NTT publishing. p. 7. ISBN 4757143222.

Jump up ^ Friday, Karl F. "Bushidō or Bull? A Medieval Historian's Perspective on the Imperial Army and the Japanese Warrior Tradition" The History Teacher, Vol. 27, No. 3 (May, 1994), pp. 340

Jump up ^ Arthur May Knapp (1896). "Feudal and Modern Japan". Retrieved 2010-01-02.[dead link]

Jump up ^ "The Zen of Japanese Nationalism," by Robert H. Sharf, in Curators of the Buddha, edited by Donald Lopez, p. 111

^ Jump up to: a b c d e William Scott Wilson, Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors (Kodansha, 1982) ISBN 0-89750-081-4

Jump up ^ "The Samurai Series: The Book of Five Rings, Hagakure -The Way of the Samurai & Bushido - The Soul of Japan" ELPN Press (November, 2006) ISBN 1-934255-01-7

Jump up ^ Meirion and Susie Harries, Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army p 7 ISBN 0-394-56935-0

Jump up ^ Eiko Ikegami. The Taming of the Samurai: Honorific Individualism and the Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Jump up ^ Karl Friday. Bushidō or Bull? A Medieval Historian's Perspective on the Imperial Army and the Japanese Warrior Tradition. The History Teacher, Volume 27, Number 3, May 1994, pages 339-349.[1]

Jump up ^ Oleg Benesch. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 0198706626, ISBN 9780198706625

Jump up ^ Herbert P. Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan p 42-3 ISBN 0-06-019314-X

Jump up ^ "No Surrender: Background History"

Jump up ^ David Powers, "Japan: No Surrender in World War Two"

Jump up ^ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p1 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

Jump up ^ Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won p 6 ISBN 0-393-03925-0

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 334 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 444 Random House New York 1970

Jump up ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 539 Random House New York 1970

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 356 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 360 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 256 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 257 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

Jump up ^ excerpt from Samurai: The World of the Warrior by Stephen Turnbull

Jump up ^ Cleary, Thomas Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook Shambhala (May, 2008) ISBN 1-59030-572-8

Jump up ^ Mikiso Hane Modern Japan: A Historical Survey, Third Edition Westview Press (January, 2001) ISBN 0-8133-3756-9

Jump up ^ Zeami Motokiyo "Atsumori"

Jump up ^ Bushido: The Soul of Japan

Jump up ^ Monumenta Nipponica

External links and further reading[edit]

Oleg Benesch. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 0198706626, ISBN 9780198706625

易經道 Yijing Dao, 鳴鶴在陰 Calling crane in the shade, Biroco - The Art of Doing Nothing, 2002-2012, 馬夏 Ma, Xia, et. al., [2]

"Bushido Arcade" a Contemporary translation of the Bushido [3]

William Scott Wilson, Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors (Kodansha, 1982) ISBN 0-89750-081-4

Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook by Thomas Cleary 288 pages Shambhala (May 13, 2008) ISBN 1-59030-572-8 ISBN 978-1590305720

Katsumata Shizuo with Martin Collcutt, "The Development of Sengoku Law," in Hall, Nagahara, and Yamamura (eds.), Japan Before Tokugawa: Political Consolidation and Economic Growth (1981), chapter 3.

K. A. Grossberg & N. Kanamoto 1981, The Laws of the Muromachi Bakufu: Kemmu Shikimoku (1336) and Muromachi Bakufu Tsuikaho, MN Monographs (Sophia UP)

Hall, John C. "Japanese Feudal Laws: the Magisterial Code of the Hojo Power Holders (1232) ." Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 2nd ser. 34 (1906)

"Japanese Feudal laws: The Ashikaga Code." Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 1st ser. 36 (1908):

John Allyn, "Forty-Seven Ronin Story" ISBN 0-8048-0196-7

Imagawa Ryoshun, The Regulations of Imagawa Ryoshun (1412 A.D.) Imagawa_Ryoshun

Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford, 1st Baron Redesdale, Final_Statement_of_the_47_Ronin (1701 A.D.)

The Message Of Master Gokurakuji — Hōjō Shigetoki (1198A.D.-1261A.D.) Hojo_shigetoki

Sunset of the Samurai--The True Story of Saigo Takamori Military History Magazine

Onoda, Hiroo, No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War. Trans. Charles S. Terry. (New York, Kodansha International Ltd, 1974) ISBN 1-55750-663-9

An interview with William Scott Wilson about Bushidō

Bushidō Website: a good definition of bushidō, including The Samurai Creed

The website of William Scott Wilson A 2005 recipient of the Japanese Government's Japan’s Foreign Minister’s Commendation, William Scott Wilson was honored for his research on Samurai and Bushidō.

Hojo Shigetoki (1198-1261)and His Role in the History of Political and Ethical Ideas in Japan by Carl Steenstrup; Curzon Press (1979)ISBN 0-7007-0132-X

A History of Law in Japan Until 1868 by Carl Steenstrup; Brill Academic Publishers;second edition (1996) ISBN 90-04-10453-4

Bushido — The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe (1905) (ISBN 0-8048-3413-X)

Budoshoshinshu - The Code of The Warrior by Daidōji Yūzan (ISBN 0-89750-096-2)

Hagakure-The Book of the Samurai By Tsunetomo Yamamoto (ISBN 4-7700-1106-7 paperback, ISBN 4-7700-2916-0 hardcover)

Go Rin No Sho - Miyamoto Musashi (1645) (ISBN 4-7700-2801-6 hardback, ISBN 4-7700-2844-X hardback Japan only)

The Unfettered Mind - Writings of the Zen Master to the Sword master by Takuan Sōhō (Musashi's mentor) (ISBN 0-87011-851-X)

The Religion of the Samurai (1913 original text), by Kaiten Nukariya, 2007 reprint by ELPN Press ISBN 0-9773400-7-4

Tales of Old Japan by Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford (1871) reprinted 1910

Sakujiro Yokoyama's Account of a Samurai Sword Duel

Death Before Dishonor By Masaru Fujimoto — Special to The Japan Times: Dec. 15, 2002

Osprey, "Elite and Warrior Series" Assorted. [4]

Stephen Turnbull, "Samurai Warfare" (London, 1996), Cassell & Co ISBN 1-85409-280-4

Lee Teng-hui, former President of the Republic of China, "武士道解題 做人的根本 蕭志強譯" in Chinese,前衛, "「武士道」解題―ノーブレス・オブリージュとは" in Japanese,小学館,(2003), ISBN 4-09-387370-4