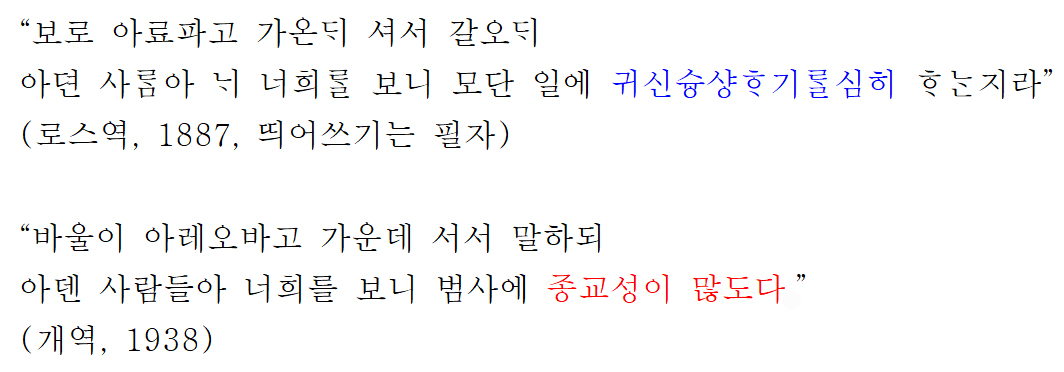

INTELLECTUAL DISCOURSE, 2009

VOL 17, NO 2, 147-158

The Significance of Toshihiko Izutsu’s Legacy for

Comparative Religion

Kojiro Nakamura*

Abstract: Toshihiko Izutsu explored the Oriental philosophies and clarified their comprehensive structural framework by using comparative philosophy and linguistic philosophy. Izutsu made three contributions that are deemed especially crucial to the study of comparative religion.

- First, the attitude of empathy he proposed and applied to himself, and his strict methodology of semantics in interpreting philosophical texts. This attitude is also important when one is trying to understand the faith of others.

- Second, his delineation of the scheme of the basic structure of Oriental philosophy for the comparative study of religions.

- Third, his study of Oriental (mystical) philosophy is a significant contribution to the study of mysticism. However, there are still problems which remain to be addressed in comparative religion.

Keywords: Oriental

philosophy, Zen, articulation,

Sufism, mysticism, comparative

religion, comparative philosophy

*Kojiro Nakamura is Professor Emeritus at the Department of Islamic Studies, Faculty of Letters, University of Tokyo, Japan. E-mail: nakakoji@m3.gyao.ne.jp.

INTELLECTUAL DISCOURSE, VOL 17, NO 2, 2009

In understanding Izutsu’s academic legacy, there are four points to bear in mind.

The first is Izutsu’s relation to Buddhism, particularly Zen Buddhism. His father was a practicing lay Zen Buddhist, and Izutsu was strictly taught by his father to read Chinese classics in this field and to practice Zen meditation beginning in his childhood. Later he became interested in Western literature and culture, in reaction to this Orientalism of his family, and he went so far as to write a book in two parts in Japanese on ancient Greek mysticism. This is one of the titles he wrote in his twenties.1 Incredibly he wrote the second part of it, while bedridden with a serious illness. However, his implicit inner attachment to Buddhism, or something spiritual, can be seen in the fact that the main subject of the work was mysticism in ancient Greek thought. Since Zen is a type of mysticism in Izutsu’s view, this concern with mysticism continued to influence his later interest in Oriental philosophy at large.

The second point to bear in mind is his

interest in language, which led him to get involved in the study of

linguistics, especially semantics, linguistic philosophy and semiotics. Because

of his extraordinary memory, he is said to have mastered more than twenty

languages, and he showed particular interest in difficult languages as Arabic

and Sanskrit, rather than modern Western languages.

He also reportedly read through the whole

Qur´Én in Arabic only a month after he finished the Arabic grammar. This

linguistic talent made it possible for him to have a deep understanding from

inside of such major traditions of Oriental philosophy as Islamic mystical

philosophy, Indian philosophy and Chinese philosophy, through his own

philological and semantic interpretation of the original texts and sources.

His interest in language may also be traced

back to Zen Buddhism, according to which the ultimate Truth (Satori, or Enlightenment) cannot be

grasped by language (reason), or intellectual learning, but should be directly

and personally experienced. Thus the

practice - especially sitting cross-legged in meditation (zazen) - is emphasised, as is often said, “Not to depend upon words

(HuryË monji ),” and “No scriptures

to rely upon (Kyoge betsuden).” In

other words, a word or name (signifiant)

is conventionally believed to have a fixed, delimited meaning or substance (signifié), exactly corresponding to the

external object. This hypostatisation of the named or the semantic content is

radically denied in Zen Buddhism, and the voidness of all things is advocated

instead. This unique view of language, which is more or less commonly shared by

MahÉyÉna Buddhism in general, may have aroused his interest in linguistics.2

Incidentally, being dissatisfied with

traditional linguistics which deals with the language phenomena (langue) only at the surface level of

human consciousness as a social institution, he drew attention to the deepest

level of subconsciousness, called the Ólaya

(Storehouse) - Consciousness in the YogÉcÉra School of Buddhism, and

proposed to see the source of the language-producing process and called it the

“Language -Ólaya - Consciousness.”3

The third point to be considered is his

inclination towards postmodernism, namely, the current of the contemporary new

thought since Ferdinand de Saussure, represented by Roland Barthes, Jacque

Lacan, and Jacque Derrida. Izutsu had a personal acquaintance with Derrida,

about whom he says, “The ‘deconstructed’ world as depicted by Derrida is …

anything but stable, constant and solid, and all is floating. This image - experience of his is, I find,

the most interesting point of his thought. For this is the world, according to

the Buddhist viewpoint, to be seen in contemplation next to the stage of the

annihilation of the ten thousand things.”4 Izutsu also wrote, “I think mysticism in general is in a sense an operation

of déconstruction in the traditional

religion.”5 These words evidently

show a close affinity between the thought of déconstruction and Buddhism, and Oriental thought at large.

The fourth and final point is his interest

in comparative philosophy. According to Izutsu, it was at a low ebb at that

time, due to a lack of systematic methodology. In order to make this field of

study truly successful, therefore, it was necessary to establish the common

basis for comparison, namely, the “meta-philosophy” of philosophies. As the

first step, he explored the basic structure of all the Oriental philosophy.

Thus, he started “a careful semantic analysis of the structure of the

key-concepts of each philosophical system.”6 Behind this interest in comparative philosophy, we see his

existential concern with the uniqueness and present-day significance of

Oriental philosophy, at the time when the traditional paradigm of Western civilisation “began to show

bankruptcy in various aspects.”7

This thought seems to have been strengthened

after 1967, when he began to participate in the Eranos Conference in

Switzerland and give lectures on Oriental philosophy. He came back to Japan

from Iran after the Revolution in 1979, and he wrote, seemingly more

assiduously, many books and articles in Japanese on Oriental thought and its

significance.

At this juncture, the name of Daisetsu Suzuki (1870-1966) comes to mind. He was a great Zen master and scholar, who introduced for the first time Zen Buddhism widely to the West by writing many books and essays on Zen in English. He also asserted the limitation of Western civilisation based on ego-centrism and the subject-object dichotomy in cognition (Hunbetsu) or discursive thinking. Furthermore he stressed the significance of the Zen Buddhist state of “consciousness of nothing” (Muhunbetsu) or the metaphysical state of emptiness and nothingness (Muga, or Non-ego). In passing, Suzuki’s friend and world-famous philosopher, Kitaro Nishida (18701945) is well known for his unique philosophical system, constructed upon this Zen experience (“pure experience”) in Western philosophical terms and methods.

Izutsu and Suzuki apparently shared the same

concern in this way, but they differed greatly in their styles of expression

and presentation. On the one hand, Suzuki taught directly the unique logic of

Zen Buddhism as Oriental religion and its present-day significance, that is, Sokuhi no ronri, or the logic of

“Identity of contradiction,” namely, “A is A, because A is non-A.” On the other hand, Izutsu explored the inner

structure common to the various schools of Oriental philosophy at large,

including Zen Buddhism, by way of comparison based on strict methodology. Thus,

Izutsu, as an Oriental intellectual, provided more systematic, general and

persuasive arguments and clarified to the Westerners the importance of Oriental

philosophy.

The Basic Structure of Oriental

Philosophy

Izutsu studied the various systems of

Oriental philosophy one by one with a view to constructing their

meta-philosophy. The basic structure was already shown in his early English

work published in two volumes in 1966-67, entitled A Comparative Study of the Key Philosophical Concepts in Sufism and

Taoism, a comparative study of Ibn ÑArabÊ, Lao-Tzu, and Chuang-Tzu.8

Both Sufism and Taoism contend that there is

a five-layered structure of being, the first layer of which is called “an

absolute Mystery” or “Zero-point of being,” meaning the absolutely

unknown-unknowable stage transcending all differentiation, articulation and

limitation (AÍad, WujËd, Mystery of

Mysteries, Chaos). It is the world of voidness or nothingness, not in the sense

of nihil or vacuum, contrary to existence or being; it is the world beyond both

existence and non-existence. It is the world of plenitude, full of energy, with

no name and thus chaotic. There are, under this first layer, four levels, the

last of which is the phenomenal world. Each layer is the process of the

ontological evolution, selfmanifestation or articulation of the first absolute

Mystery. In this sense all beings are ultimately one.

The layers or strata,

according to Ibn ÑArabÊ, are:

1.

The stage of the Essence (the

absolute Mystery, abysmal Darkness),

2.

The stage of the Divine

Attributes and Names (the stage of Divinity),

3.

The stage of the Divine Actions

(the stage of Lordship), 4. The

stage of Images and Similarities,

5. The sensible world.

And according to Lao-Tzu, they are:

1.

Mystery of Mysteries,

2.

Non-Being (Nothing, or

Nameless),

3.

One,

4.

Being (Heaven and Earth),

5.

The ten thousand things.9

Such a change of external

reality corresponds to the epistemological transformation of human

consciousness and cognition. Thus, the world of “an absolute Mystery” is the

state where the egoconsciousness and the subject-object dichotomy in cognition

have completely disappeared together with all differentiation and multiplicity,

and all is unified. In classical Sufism, this is usually called “fanÉ´” (annihilation [of ego-consciousness]) or “fanÉ´alfanÉ´.”

The above-mentioned manifestation of “an absolute Mystery” down to the phenomenal world goes along with the downward change of consciousness from the state of unity, or the “consciousness of nothing” to the ordinary state of consciousness, namely, consciousness of something. This descending change of consciousness naturally presupposes and runs parallel with the ascending movement from the ordinary consciousness in the opposite direction. And all this corresponds to the change of the external reality. Izutsu shows this process in the following diagram:10

Non-articulation

![]()

Articulation(1)

Articulation(2)

“Articulation(1)” means the ordinary world divided and ordered by words and concepts, or the world of logos, while “Nonarticulation” is the world of no distinction of subject and object, the world of “an absolute Mystery,” nothingness and chaos, transcending the differentiation and limitation by words and concepts. It is the world of Reality where all is one, seamless and transparent. This state turns back and goes down again to “Articulation(2)” before long and the subject-object division becomes reinstated.

Although it comes back to the ordinary world of differentiation, however, it does not return to the same state as it was before. After the strong experience of non-articulation and oneness where all is united, a radical change is produced in human consciousness. Even though one is back to the world of verbal and semantic divisions, he does not see the differentiation and conceptualisation by words and names as absolute, solid and permanent any more. He regards it rather as provisional, and there remains the vision of unity of the whole multiplied world and reality. “The result is that they (namely, all things) interpenetrate each other and fuse into one another. Every single thing, while being a limited, particular thing, can be and is anything; indeed it is all other things.”11 “All things are articulated and non-articulated at the same time.”12 This is what is called “Muhunbetsu no hunbetsu” (Conceptual thinking of non-thinking) in Zen Buddhism (See the aforementioned Sokuhi no ronri, namely, “A is A, because A is non-A”) and “baqÉ´” (remaining) in classical Sufism. This is the basic structure of Oriental philosophy as presented by Izutsu. Although the concrete terminology and details are different according to the traditions of philosophy, the main framework remains the same, as Izutsu remarkably shows in the metaphilosophical terminology of articulation.

Another characteristic of Oriental philosophy is the way or the methodology of discipline and practice prepared for reaching the goal of non-articulation, such as the “Mystical ladder” (maqÉmÉt) in Sufism and the direct training system of novices by the masters, for normally it is not possible to reach such an “extraordinary” state naturally, but only through human effort and exercise.

Izutsu’s Legacy and Comparative

Religion

It goes without saying that

there are differences between comparative philosophy and comparative religion

or the history of religions in goal and methodology, but there are also common

elements, one of which is the researcher’s attitude in approaching the subject

of study and understanding. Izutsu explains his study of Ibn ÑArabÊ and Lao-Tzu’s mystical philosophy as follows:

I emphasised the necessity of our approaching the subject

with an attitude of ‘empathy,’ a particular kind of sympathetic intention, by

which alone we could at all hope to reach the personal existential depth from

which the thought wells forth. Exactly the same attitude is required with

regard to Lao-Tzu.13

This internal approach

is also extremely important for the study of

comparative religion as well as for mutual understanding and dialogue among

religions. In comparative religion, the objectivity of study has been

emphasised in an attempt to demonstrate its difference and independence from

theology from its inception in the 19th Century in Europe. Nowadays, there is even a reductionist tendency

to deny the proper nature (sui generis)

of religious phenomena, and thus the identity of comparative religion itself.

However, even though objectivity is necessary in the study of religions, the

internal empathetic approach is basically very important as well. In this

regard, Izutsu’s methodology is extremely significant, and there are many

things we should learn from it.

Next, comparison is a common basic method in

both comparative philosophy and comparative religion. For this purpose, a

common language (meta-philosophy) is necessary as a standard for comparison,

and Izutsu explored it for Oriental philosophy as mentioned before. The same is

true with comparative religion. In this latter case, however, religions of the

world are so many and so complex that, apart from the established religions,

there are ambiguous phenomena which are difficult to classify into religion.

Thus, a standard is needed to select a religion for comparison. This

standard is called the

“hypothetical definition” of religion which is totally provisional and

different from the final answer to the question, “What is religion?” posited as

the ultimate goal of comparative religion. For this reason, it is called the

“hypothetical definition.” Since it is temporal, it becomes more minute and

closer to reality as the study of religion progresses and our understanding of

it becomes deeper.

At any rate, this hypothetical definition is

supposed to apply to all religions and become a common language and standard

for the comparative study of religions. In this sense, the inner structure of

Oriental philosophy which Izutsu presented as meta-philosophy gives a very

useful suggestion to comparative religion. Furthermore, when limited to

Oriental philosophy, Izutsu’s framework can become a common standard for mutual

understanding and dialogue. For example, bearing the previous-mentioned diagram

in mind, Muslims can approach Zen Buddhists of Japan and Taoists of China by

checking the key terms and concepts of their partner’s thinking which

correspond to those of Ibn ÑArabÊ’s mystical thought.

In the case of Ibn ÑArabÊ, though, the

orthodoxy of his thought may be a problem for some Muslims. In fact, he was

often accused of being unorthodox. This has to do with another important

question for the comparative study of religions. Unless we take the position

that mysticism is the highest type of religions, as suggested by Frithjof

Schuon, we have to clarify the relation between mystic and nonmystic religions

as two different, but equal expressions of faith. However, since Izutsu, as a

comparative philosopher, does not dwell upon this matter extensively, we will

not argue the problem any further here. All we can say at this juncture is that

we need some sort of typology of religions, such as “mystical” and “prophetic,”14

“mystical” and “numinous,”15 “mystical or ontological” and “ethical or moral,”16 and “interiority” type and “confrontation” type.17 The important thing, however, is what Izutsu calls an “empathetic”

approach and a tolerant attitude, namely, to understand the other persons from

inside, or from their own standpoint on the same common ground, rather than to

see others from one’s own viewpoint. Only in this way will mutual understanding

and dialogue among religions and sects be possible. In Japan a high level of

dialogue between Buddhists and Christians has already begun, but unfortunately

such a dialogue has not been attempted with Muslims yet. The results of

Izutsu’s efforts would be very useful for improving this situation.

Third, what Izutsu calls “Oriental

philosophy” is actually mystical philosophy, namely, the philosophical,

conceptual expression of mystical experience. If so, his academic achievements

are a great contribution to the study of religious mysticism. For example, he

stressed mysticism as a complex phenomenon consisting of both ascending (anabasis) and descending (katabasis) ways. This comprehensive

approach is very important, considering the fact that the study of mysticism

has been mainly concerned with the ascending way to the goal of mystical

experience.

The next is his attempt to formulate a

typology of mysticism. He discussed two types. One is the mysticism of love

toward a personal God, the Absolute, represented by Junayd (d. 910) of Islam

and RÉmÉnuja (d. 1137) of India. The other is the mysticism of the union with

the impersonal Absolute Being and of self-deification, represented by AbË YazÊd

BastÉmÊ (d. 874 or 877) of Islam and Shankara (d. ca. 750) of India. Izutsu gave another classification of mysticism.

One is atheistic or non-theistic mysticism (Brahmanism, MahÉyÉna Buddhism,

including Zen), and the other is theistic mysticism. The latter is further

classified into polytheistic mysticism (Shamanism) and monotheistic mysticism.

This latter typology is basically the same

as the former. That is to say, one takes the absolute impersonal non-articulate

mystical experience transcending the subject-object bifurcation as the ultimate

state, while the other asserts that the true personal relation of love is only

realisable after that impersonal mystical experience. The former is represented

by Ibn ÑArabÊ and the latter by Junayd in the case of Islam. The difference,

however, seems to be merely that of emphasis. If we can understand the

difference between the two types this way, we may probably expect a new vista

of possibility for solving the problem of Ibn ÑArabÊ’s orthodoxy in that

direction. Unfortunately, Izutsu did not

elaborate on this problem.

At this juncture, the name of another

polyglot scholar and perennialist, the aforementioned Frithjof Schuon

(1907-1998) of Switzerland who belonged to the same generation as Izutsu,18 comes to mind. He was admitted into the ÑAlawÊ ØËfÊ ÙarÊqah (Order)

by the founder, Shaykh AÍmad ÑAlÉwÊ (1869-1934) himself and given the Muslim

name, ÑÔsÉ NËr al-DÊn Ahmad. Schuon also studied many other religions and

asserted the transcendent unity of all religions in their inner deepest

essence,19 calling it “philosophia perennis.”20

This does not mean the unity in the actual

visible phenomenal state of religions, but in the unknowable absolute Truth,

transcending verbal expressions and forms, which they universally share. Schuon

calls the former “exoterism,” and the latter “esoterism.”

Schuon and Izutsu both showed a major

interest in mysticism, but the former expressed it as “Esoterism,” and the

latter “Oriental philosophy.” What is the reason for this difference? There may

have been a difference in personal existential inclination. Izutsu’s concern

might have been to assert as an Oriental intellectual the uniqueness of

Oriental philosophy against Western philosophy, while Schuon’s was to search

for his own identity as a Western intellectual facing the problems of modernity

after “the death of God.”

Conclusion

In the foregoing, we have

discussed part of Izutsu’s academic achievements. His major concern was to

study Oriental philosophy and clarify its comprehensive structural framework by

comparative philosophy and linguistic philosophy. He read the original texts of

philosophical Sufism, Mahayana Buddhism (especially Zen Buddhism), Jewish Kabbalism, Vedantine philosophy,

Taoist philosophy of Lao-Tzu, Chuang-Tzu, and others.

This framework is significant for the study of mysticism as part of the

human religious phenomenon. While mystical experience has so far been stressed

and the discussions mostly tend to turn around it, he also emphasised the

transformed state of post-experience consciousness and its influence in daily

life.

Furthermore, his scheme also serves not only

as a navigator for correct understanding in the labyrinth of Oriental

philosophy, but also for comparative study of religions and mutual

understanding among them. It is the first premise of comparative religion and

mutual understanding to have a common basis, and here we have one. Whether a

theist or a non-theist, unless both sides mutually admit that they stand

on common ground, any meaningful

dialogue or understanding is not possible. A Zen Buddhist can explain his

teachings according to Izutsu’s framework to a Sufi of the Ibn ÑArabÊ school

and vice versa. Also important in this connection is Izutsu’s proposed attitude

of empathy as well as his strict methodology of semantics in reading and

interpreting the texts.

But the problem is how to find a common

framework or metalanguage between the “Oriental” (or mystical) and

non-“Oriental” (or non-mystical) schools (sects) and religions. Another

question is how to incorporate the faith of the common people in the total

understanding of religion, since philosophy is not religion. But these are

problems rather for comparative religionists, or historians of religion.

![]()

Notes

1.

It was published in two separate

parts: one is entitled “Natural Mysticismand Ancient Greece” and the other “The

Philosophical Development of Greek Mysticism.” Both are collected into Selected Works, Vol. I, under the title

“Mystical Philosophy.” See Toshihiko Izutsu, Selected Works of Toshihiko Izutsu, 11 vols. (Tokyo: Chuokoronsha, 1991-1993).

2.

Worth mentioning here is one of his

earliest English works, Toshihiko Izutsu,Language

and Magic: Studies in the Magical Function of Speech (Tokyo: Keio

University, 1956).

3.

Izutsu, Selected Works, vol. ix, 68.

4.

Ibid., Supplement, 236.

5.

Ibid., vol. ix, 460.

6.

Toshihiko Izutsu, The Concept and Reality of Existence (Tokyo:

The Keio Institute of Cultural and Linguistic Studies, 1971), 36.

7.

Izutsu, Selected Works, Supplement, 53.

8.

This work was later republished

with revisions under a new title, Sufism

and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts (California:

University of California Press, 1983).

9.

Toshihiko Izutsu, A Comparative Study of the Key

Philosophical Concepts in Sufism and Taoism: Ibn ÑArabÊ and Lao-Tzu, Chuang-Tzu, 2 vols. (Tokyo: The Keio Institute of Cultural and

Linguistic Studies, 1966-67), vol.

ii, 203; idem, Sufism and Taoism,

481.

10. Toshihiko

Izutsu, Selected Works, vol. vi, 120;

idem, Toward a Philosophy of Zen Buddhism

(Boulder: PrajñÉ Press, 1982), 145.

11. Izutsu,

Toward a Philosophy of Zen Buddhism,

128.

12. Ibid.,

127.

13. Izutsu, A Comparative Study of the Key

Philosophical Concepts in Sufism and Taoism, vol. ii, 9. This part is

deleted in the new edition, Sufism and

Taoism, but I do not think this deletion reflects a change in his view.

14. Friedrich

Heiler, Prayer: A Study in the History

and Psychology of Religion (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 1932), ch. vi.

15. Ninian

Smart, World Religions: A Dialogue

(Pelican Books, 1966), 27.

16. P.

Tillich, Christianity and the Encounter

of World Religions (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963), 54; idem, Dynamics of Faith (New York: Harper

& Row, 1958), 56.

17. L.

Peter Berger, ed., The Other Side of God:

A Polarity in World Religions (Garden City: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1981).

18. Jean-Baptiste

Aymard, P. Laude, Frithjof Schuon: Life

and Teachings (New York: State University of New York Press, 2004).

19. Frithjof

Schuon, The Transcendent Unity of

Religions (Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993).

20. Frithjof

Schuon, Islam and the Perennial

Philosophy (World of Islam Festival Publishing, 1976), 195. He also calls

it “sophia perennis.” Interestingly

enough, Izutsu also used this term once as far as I know. See, Izutsu, A Comparative Study of the Key

Philosophical Concepts in Sufism and Taoism, vol. ii, 191; idem, Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of

Key Philosophical Concepts, 4.

21.