Gospel of John

The Gospel according to John (Greek: Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, romanized: Euangélion katà Iōánnēn, also known as the Gospel of John, or simply John) is the fourth of the four canonical gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the resurrection of Jesus) and seven "I am" discourses culminating in Thomas's proclamation of the risen Jesus as "my Lord and my God";[1] the concluding verses set out its purpose, "that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name."[2][3]

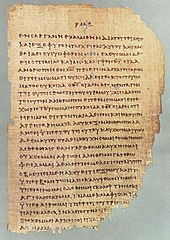

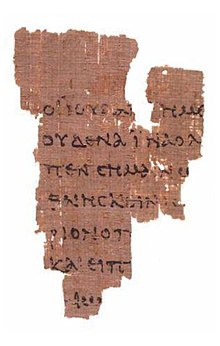

John reached its final form around AD 90–110,[4] although it contains signs of origins dating back to AD 70 and possibly even earlier.[5] Like the three other gospels, it is anonymous, although it identifies an unnamed "disciple whom Jesus loved" as the source of its traditions.[6][7] It most likely arose within a "Johannine community",[8][9] and as it is closely related in style and content to the three Johannine epistles most scholars treat the four books, along with the Book of Revelation, as a single corpus of Johannine literature, albeit not from the same author.[10]

The discourses seem to be concerned with issues of the church–synagogue debate at the time of composition.[11]

Composition[edit]

| Part of a series of articles on |

| John in the Bible |

|---|

|

| Johannine literature |

| Authorship |

| Related literature |

| See also |

Composition[edit]

The gospel of John, like all the gospels, is anonymous.[12] John 21:24-25 references a Beloved Disciple, stating of him: "This is the disciple who is testifying to these things and has written them, and we know that his testimony is true; but there are also many other things that Jesus did; if all of them were written down, I suppose that the world itself would not contain the books that would be written."[8] Early Christian tradition, first attested by Irenaeus (c. 130 – c. 202 AD), identified this disciple with John the Apostle, but most scholars have abandoned this hypothesis or hold it only tenuously[13] – for example, the gospel is written in good Greek and displays sophisticated theology, and is therefore unlikely to have been the work of a simple fisherman.[14] These verses imply rather that the core of the gospel relies on the testimony (perhaps written) of the "disciple who is testifying", as collected, preserved and reshaped by a community of followers (the "we" of the passage), and that a single follower (the "I") rearranged this material and perhaps added the final chapter and other passages to produce the final gospel.[8] (Recent arguments by Richard Bauckham and others that John's gospel preserves eyewitness testimony have not won general acceptance).[15][16]

Most scholars believe that John reached its final form around AD 90–110.[4] Given its complex history there may have been more than one place of composition, and while the author was familiar with Jewish customs and traditions, his frequent clarification of these implies that he wrote for a mixed Jewish/Gentile or Jewish context outside Palestine. The author may have drawn on a "signs source" (a collection of miracles) for chapters 1-12, a "passion source" for the story of Jesus's arrest and crucifixion, and a "sayings source" for the discourses, but these hypotheses are much debated.[17] He seems to have known some version of Mark and Luke, as he shares with them some items of vocabulary and clusters of incidents arranged in the same order,[18][19] but key terms from those gospels are absent or nearly so, implying that if he did know them he felt free to write independently.[19] The Hebrew scriptures were an important source,[20] with 14 direct quotations (versus 27 in Mark, 54 in Matthew, 24 in Luke), and their influence is vastly increased when allusions and echoes are included.[21] The majority of John's direct quotations do not agree exactly with any known version of the Jewish scriptures.[22]

Setting: the Johannine community debate[edit]

For much of the 20th century scholars interpreted John within the paradigm of a Johannine community,[23] meaning that the gospel sprang from a late 1st century Christian community excommunicated from the Jewish synagogue (probably meaning the Jewish community)[24] on account of its belief in Jesus as the promised Jewish messiah.[25] This interpretation, which saw the community as essentially sectarian and standing outside the mainstream of early Christianity, has been increasingly challenged in the first decades of the 21st century,[26] and there is currently considerable debate over the social, religious and historical context of the gospel.[27] Nevertheless, the Johannine literature as a whole (made up of the gospel, the three Johannine epistles, and Revelation), reveals a community holding itself distinct from the Jewish culture from which it arose while cultivating an intense devotion to Jesus as the definitive revelation of a God with whom they were in close contact through the Paraclete.[28]

Structure and content[edit]

The majority of scholars see four sections in John's gospel: a prologue (1:1–18); an account of the ministry, often called the "Book of Signs" (1:19–12:50); the account of Jesus' final night with his disciples and the passion and resurrection, sometimes called the "book of glory" (13:1–20:31); and a conclusion (20:30–31); to these is added an epilogue which most scholars believe did not form part of the original text (Chapter 21).[29][30]

- The prologue informs readers of the true identity of Jesus, the Word of God through whom the world was created and who took on human form;[31] he came to the Jews and the Jews rejected him, but "to all who received him (the circle of Christian believers), who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God."[32]

- Book of Signs (ministry of Jesus): Jesus is baptized, calls his disciples, and begins his earthly ministry.[33] He travels from place to place informing his hearers about God the Father in long discourses, offering eternal life to all who will believe, and performing miracles which are signs of the authenticity of his teachings, but this creates tensions with the religious authorities (manifested as early as 5:17–18), who decide that he must be eliminated.[33][34]

- The Book of Glory tells of Jesus's return to his heavenly father: it tells how he prepares his disciples for their coming lives without his physical presence and his prayer for himself and for them, followed by his betrayal, arrest, trial, crucifixion and post-resurrection appearances.[34]

- The conclusion sets out the purpose of the gospel, which is "that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name."[2]

- Chapter 21, the addendum, tells of Jesus' post-resurrection appearances in Galilee, the miraculous catch of fish, the prophecy of the crucifixion of Peter, and the fate of the Beloved Disciple.[2]

The structure is highly schematic: there are seven "signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the resurrection of Jesus), and seven "I am" sayings and discourses, culminating in Thomas's proclamation of the risen Jesus as "my Lord and my God" (the same title, dominus et deus, claimed by the Emperor Domitian, an indication of the date of composition).[1]

Theology[edit]

Christology[edit]

John's "high Christology" depicts Jesus as divine, preexistent, and identified with the one God,[35] talking openly about his divine role and echoing Yahweh's "I Am that I Am" with seven "I Am" declarations of his own:[36]

- "I am the bread of life"[6:35]

- "I am the light of the world"[8:12]

- "I am the gate for the sheep"[10:7]

- "I am the good shepherd"[10:11]

- "I am the resurrection and the life"[11:25]

- "I am the way and the truth and the life"[14:6]

- "I am the true vine"[15:1]

Yet scholars agree that while John clearly regards Jesus as divine, he just as clearly subordinates him to the one God.[37]

Logos[edit]

In the prologue, the gospel identifies Jesus as the Logos or Word. In Ancient Greek philosophy, the term logos meant the principle of cosmic reason.[38] In this sense, it was similar to the Hebrew concept of Wisdom, God's companion and intimate helper in creation. The Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo merged these two themes when he described the Logos as God's creator of and mediator with the material world. According to Stephen Harris, the gospel adapted Philo's description of the Logos, applying it to Jesus, the incarnation of the Logos.[39]

Another possibility is that the title Logos is based on the concept of the divine Word found in the Targums (Aramaic translation/interpretations recited in the synagogue after the reading of the Hebrew Scriptures). In the Targums (which all post-date the first century but which give evidence of preserving early material), the concept of the divine Word was used in a manner similar to Philo, namely, for God's interaction with the world (starting from creation) and especially with his people, e.g. Israel, was saved from Egypt by action of "the Word of the LORD," both Philo and the Targums envision the Word as being manifested between the cherubim and the Holy of Holies, etc.[40]

Cross[edit]

The portrayal of Jesus' death in John is unique among the four Gospels. It does not appear to rely on the kinds of atonement theology indicative of vicarious sacrifice (cf. Mark 10:45, Romans 3:25) but rather presents the death of Jesus as his glorification and return to the Father. Likewise, the three "passion predictions" of the Synoptic Gospels (Mark 8:31, 9:31, 10:33–34 and pars.) are replaced instead in John with three instances of Jesus explaining how he will be exalted or "lifted up"(John 3:14, 8:28, 12:32). The verb for "lifted up" (Greek: ὑψωθῆναι, hypsōthēnai) reflects the double entendre at work in John's theology of the cross, for Jesus is both physically elevated from the earth at the crucifixion but also, at the same time, exalted and glorified.[41]

Sacraments[edit]

Scholars disagree both on whether and how frequently John refers to sacraments, but current scholarly opinion is that there are very few such possible references, that if they exist they are limited to baptism and the Eucharist.[42] In fact, there is no institution of the Eucharist in John's account of the Last Supper (it is replaced with Jesus washing the feet of his disciples), and no New Testament text that unambiguously links baptism with rebirth.[43]

Individualism[edit]

In comparison to the synoptic gospels, the fourth gospel is markedly individualistic, in the sense that it places emphasis more on the individual's relation to Jesus than on the corporate nature of the Church.[44][45] This is largely accomplished through the consistently singular grammatical structure of various aphoristic sayings of Jesus throughout the gospel.[44][Notes 1] According to Richard Bauckham, emphasis on believers coming into a new group upon their conversion is conspicuously absent from John.[44] There is also a theme of "personal coinherence", that is, the intimate personal relationship between the believer and Jesus in which the believer "abides" in Jesus and Jesus in the believer.[45][44][Notes 2] According to C. F. D. Moule, the individualistic tendencies of John could potentially give rise to a realized eschatology achieved on the level of the individual believer; this realized eschatology is not, however, to replace "orthodox", futurist eschatological expectations, but is to be "only [their] correlative."[46]

John the Baptist[edit]

John's account of the Baptist is different from that of the synoptic gospels. In this gospel, John is not called "the Baptist."[47] The Baptist's ministry overlaps with that of Jesus; his baptism of Jesus is not explicitly mentioned, but his witness to Jesus is unambiguous.[47] The evangelist almost certainly knew the story of John's baptism of Jesus and he makes a vital theological use of it.[48] He subordinates the Baptist to Jesus, perhaps in response to members of the Baptist's sect who regarded the Jesus movement as an offshoot of their movement.[49]

In John's gospel, Jesus and his disciples go to Judea early in Jesus' ministry before John the Baptist was imprisoned and executed by Herod. He leads a ministry of baptism larger than John's own. The Jesus Seminar rated this account as black, containing no historically accurate information.[50] According to the biblical historians at the Jesus Seminar, John likely had a larger presence in the public mind than Jesus.[51]

Gnosticism[edit]

In the first half of the 20th century, many scholars, primarily including Rudolph Bultmann, have forcefully argued that the Gospel of John has elements in common with Gnosticism.[49] Christian Gnosticism did not fully develop until the mid-2nd century, and so 2nd-century Proto-Orthodox Christians concentrated much effort in examining and refuting it.[52] To say John's gospel contained elements of Gnosticism is to assume that Gnosticism had developed to a level that required the author to respond to it.[53] Bultmann, for example, argued that the opening theme of the Gospel of John, the pre-existing Logos, along with John's duality of light versus darkness in his Gospel were originally Gnostic themes that John adopted. Other scholars (e.g., Raymond E. Brown) have argued that the pre-existing Logos theme arises from the more ancient Jewish writings in the eighth chapter of the Book of Proverbs, and was fully developed as a theme in Hellenistic Judaism by Philo Judaeus.[54] The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran verified the Jewish nature of these concepts.[55] April DeConick has suggested reading John 8:56 in support of a Gnostic theology,[56] however recent scholarship has cast doubt on her reading.[57]

Gnostics read John but interpreted it differently from the way non-Gnostics did.[58] Gnosticism taught that salvation came from gnosis, secret knowledge, and Gnostics did not see Jesus as a savior but a revealer of knowledge.[59] Barnabas Lindars asserts that the gospel teaches that salvation can only be achieved through revealed wisdom, specifically belief in (literally belief into) Jesus.[60]

Raymond Brown contends that "The Johannine picture of a savior who came from an alien world above, who said that neither he nor those who accepted him were of this world,[61] and who promised to return to take them to a heavenly dwelling[62] could be fitted into the gnostic world picture (even if God's love for the world in 3:16 could not)."[63] It has been suggested that similarities between John's gospel and Gnosticism may spring from common roots in Jewish Apocalyptic literature.[64]

Comparison with other writings[edit]

Synoptic gospels and Pauline literature[edit]

The Gospel of John is significantly different from the synoptic gospels in the selection of its material, its theological emphasis, its chronology, and literary style, with some of its discrepancies amounting to contradictions.[65] The following are some examples of their differences in just one area, that of the material they include in their narratives:[66]

| Material found in the Synoptics but absent from John | Material found in John but absent from the Synoptics |

|---|---|

| Narrative parables | Symbolic discourses |

| The Kingdom of God | Teaching on eternal life |

| The end-time (or Olivet) discourse | Emphasis on realized eschatology |

| The Sermon of the Mount and Lord's Prayer | Jesus's "farewell discourse" |

| The baptism of Jesus by John | Interaction between Jesus and John |

| The institution of the Lord's Supper | Jesus as the "bread of heaven" |

| The Transfiguration of Jesus | Scenes in the upper room |

| The Temptation of Jesus by Satan | Satan as Jesus's antagonist working through Judas |

| Exorcism of demons | No demon exorcisms |

In the Synoptics, the ministry of Jesus takes a single year, but in John it takes three, as evidenced by references to three Passovers. Events are not all in the same order: the date of the crucifixion is different, as is the time of Jesus' anointing in Bethany and the cleansing of the Temple, which occurs in the beginning of Jesus' ministry rather than near its end.[67]

Many incidents from John, such as the wedding in Cana, the encounter of Jesus with the Samaritan woman at the well, and the raising of Lazarus, are not paralleled in the synoptics, and most scholars believe the author drew these from an independent source called the "signs gospel", the speeches of Jesus from a second "discourse" source,[68][19] and the prologue from an early hymn.[69] The gospel makes extensive use of the Jewish scriptures:[68] John quotes from them directly, references important figures from them, and uses narratives from them as the basis for several of the discourses. The author was also familiar with non-Jewish sources: the Logos of the prologue (the Word that is with God from the beginning of creation), for example, was derived from both the Jewish concept of Lady Wisdom and from the Greek philosophers, John 6 alludes not only to the exodus but also to Greco-Roman mystery cults, and John 4 alludes to Samaritan messianic beliefs.[70]

John lacks scenes from the Synoptics such as Jesus' baptism,[71] the calling of the Twelve, exorcisms, parables, and the Transfiguration. Conversely, it includes scenes not found in the Synoptics, including Jesus turning water into wine at the wedding at Cana, the resurrection of Lazarus, Jesus washing the feet of his disciples, and multiple visits to Jerusalem.[67]

In the fourth gospel, Jesus' mother Mary, while frequently mentioned, is never identified by name.[72][73] John does assert that Jesus was known as the "son of Joseph" in 6:42. For John, Jesus' town of origin is irrelevant, for he comes from beyond this world, from God the Father.[74]

While John makes no direct mention of Jesus' baptism,[71][67] he does quote John the Baptist's description of the descent of the Holy Spirit as a dove, as happens at Jesus' baptism in the Synoptics. Major synoptic speeches of Jesus are absent, including the Sermon on the Mount and the Olivet Discourse,[75] and the exorcisms of demons are never mentioned as in the Synoptics.[71][76] John never lists all of the Twelve Disciples and names at least one disciple, Nathanael, whose name is not found in the Synoptics. Thomas is given a personality beyond a mere name, described as "Doubting Thomas".[77]

Jesus is identified with the Word ("Logos"), and the Word is identified with theos ("god" in Greek);[78] no such identification is made in the Synoptics.[79] In Mark, Jesus urges his disciples to keep his divinity secret, but in John he is very open in discussing it, even referring to himself as "I AM", the title God gives himself in Exodus at his self-revelation to Moses. In the Synoptics, the chief theme is the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Heaven (the latter specifically in Matthew), while John's theme is Jesus as the source of eternal life and the Kingdom is only mentioned twice.[67][76] In contrast to the synoptic expectation of the Kingdom (using the term parousia, meaning "coming"), John presents a more individualistic, realized eschatology.[80][Notes 3]

In the Synoptics, quotations from Jesus are usually in the form of short, pithy sayings; in John, longer quotations are often given. The vocabulary is also different, and filled with theological import: in John, Jesus does not work "miracles", but "signs" which unveil his divine identity.[67] Most scholars consider John not to contain any parables. Rather it contains metaphorical stories or allegories, such as those of the Good Shepherd and of the True Vine, in which each individual element corresponds to a specific person, group, or thing. Other scholars consider stories like the childbearing woman (16:21) or the dying grain (12:24) to be parables.[Notes 4]

According to the Synoptics, the arrest of Jesus was a reaction to the cleansing of the temple, while according to John it was triggered by the raising of Lazarus.[67] The Pharisees, portrayed as more uniformly legalistic and opposed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels, are instead portrayed as sharply divided; they debate frequently in John's accounts. Some, such as Nicodemus, even go so far as to be at least partially sympathetic to Jesus. This is believed to be a more accurate historical depiction of the Pharisees, who made debate one of the tenets of their system of belief.[82]

In place of the communal emphasis of the Pauline literature, John stresses the personal relationship of the individual to God.[83]

Johannine literature[edit]

The Gospel of John and the three Johannine epistles exhibit strong resemblances in theology and style; the Book of Revelation has also been traditionally linked with these, but differs from the gospel and letters in style and even theology.[84] The letters were written later than the gospel, and while the gospel reflects the break between the Johannine Christians and the Jewish synagogue, in the letters the Johannine community itself is disintegrating ("They went out from us, but they were not of us; for if they had been of us, they would have continued with us; but they went out..." - 1 John 2:19).[85] This secession was over Christology, the "knowledge of Christ", or more accurately the understanding of Christ's nature, for the ones who "went out" hesitated to identify Jesus with Christ, minimising the significance of the earthly ministry and denying the salvific importance of Jesus's death on the cross.[86] The epistles argue against this view, stressing the eternal existence of the Son of God, the salvific nature of his life and death, and the other elements of the gospel's "high" Christology.[86]

Historical reliability[edit]

The teachings of Jesus found in the synoptic gospels are very different from those recorded in John, and since the 19th century scholars have almost unanimously accepted that these Johannine discourses are less likely than the synoptic parables to be historical, and were likely written for theological purposes.[87] By the same token, scholars usually agree that John is not entirely without historical value: certain sayings in John are as old or older than their synoptic counterparts, his representation of the topography around Jerusalem is often superior to that of the synoptics, his testimony that Jesus was executed before, rather than on, Passover, might well be more accurate, and his presentation of Jesus in the garden and the prior meeting held by the Jewish authorities are possibly more historically plausible than their synoptic parallels.[88]

Representations[edit]

The gospel has been depicted in live narrations and dramatized in productions, skits, plays, and Passion Plays, as well as in film. The most recent such portrayal is the 2014 film The Gospel of John, directed by David Batty and narrated by David Harewood and Brian Cox, with Selva Rasalingam as Jesus. The 2003 film The Gospel of John, was directed by Philip Saville, narrated by Christopher Plummer, with Henry Ian Cusick as Jesus.

Parts of the gospel have been set to music. One such setting is Steve Warner's power anthem "Come and See", written for the 20th anniversary of the Alliance for Catholic Education and including lyrical fragments taken from the Book of Signs. Additionally, some composers have made settings of the Passion as portrayed in the gospel, most notably the one composed by Johann Sebastian Bach, although some verses are borrowed from Matthew.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Bauckham 2015 contrasts John's consistent use of the third person singular ("The one who..."; "If anyone..."; "Everyone who..."; "Whoever..."; "No one...") with the alternative third person plural constructions he could have used instead ("Those who..."; "All those who..."; etc.). He also notes that the sole exception occurs in the prologue, serving a narrative purpose, whereas the later aphorisms serve a "paraenetic function".

- ^ See John 6:56, 10:14–15, 10:38, and 14:10, 17, 20, and 23.

- ^ Realized eschatology is a Christian eschatological theory popularized by C. H. Dodd (1884–1973). It holds that the eschatological passages in the New Testament do not refer to future events, but instead to the ministry of Jesus and his lasting legacy.[81] In other words, it holds that Christian eschatological expectations have already been realized or fulfilled.

- ^ See Zimmermann 2015, pp. 333–60.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Witherington 2004, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Edwards 2015, p. 171.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 215.

- ^ a b Lincoln 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Hendricks 2007, p. 147.

- ^ Reddish 2011, pp. 13.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Reddish 2011, p. 41.

- ^ Bynum 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 479.

- ^ Lindars 1990, p. 53.

- ^ O'Day 1998, p. 381.

- ^ Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, p. 41.

- ^ Kelly 2012, p. 115.

- ^ Eve 2016, p. 135.

- ^ Porter & Fay 2018, p. 41.

- ^ Reddish 2011, p. 187-188.

- ^ Lincoln 2005, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c Fredriksen 2008, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Valantasis, Bleyle & Haugh 2009, p. 14.

- ^ Yu Chui Siang Lau 2010, p. 159.

- ^ Menken 1996, p. 11-13.

- ^ Lamb 2014, p. 2.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, p. 70.

- ^ Köstenberger 2006, p. 72.

- ^ Lamb 2014, p. 2-3.

- ^ Bynum 2012, p. 7,12.

- ^ Attridge 2006, p. 125.

- ^ Moloney 1998, p. 23.

- ^ Bauckham 2008, p. 126.

- ^ Aune 2003, p. 245.

- ^ Aune 2003, p. 246.

- ^ a b Van der Watt 2008, p. 10.

- ^ a b Kruse 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, p. 51.

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 302–10.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, pp. 53.

- ^ Greene 2004, p. p37-.

- ^ Harris 2006, pp. 302–310.

- ^ Ronning 2010.

- ^ Kysar 2007, p. 49–54.

- ^ Bauckham 2015, p. 83-84.

- ^ Bauckham 2015, p. 89,94.

- ^ a b c d Bauckham 2015.

- ^ a b Moule 1962, p. 172.

- ^ Moule 1962, p. 174.

- ^ a b Cross & Livingstone 2005.

- ^ Barrett 1978, p. 16.

- ^ a b Harris 2006.

- ^ Funk 1998, pp. 365–440.

- ^ Funk 1998, p. 268.

- ^ Olson 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Kysar 2005, pp. 88ff.

- ^ Brown 1997.

- ^ Charlesworth 2010, p. 42.

- ^ DeConick 2016, pp. 13-.

- ^ Llewelyn, Robinson & Wassell 2018, pp. 14–23.

- ^ Most 2005, pp. 121ff.

- ^ Skarsaune 2008, pp. 247ff.

- ^ Lindars 1990, p. 62.

- ^ John 17:14

- ^ John 14:2–3

- ^ Brown 1997, p. 375.

- ^ Kovacs 1995.

- ^ Burge 2014, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Köstenberger 2013, p. unpaginated.

- ^ a b c d e f Burge 2014, pp. 236–37.

- ^ a b Reinhartz 2017, p. 168.

- ^ Perkins 1993, p. 109.

- ^ Reinhartz 2017, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Funk & Hoover 1993, pp. 1–30.

- ^ Williamson 2004, p. 265.

- ^ Michaels 1971, p. 733.

- ^ Fredriksen 2008.

- ^ Pagels 2003.

- ^ a b Thompson 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Walvoord & Zuck 1985, p. 313.

- ^ Ehrman 2005.

- ^ Carson 1991, p. 117.

- ^ Moule 1962, pp. 172–74.

- ^ Ladd & Hagner 1993, p. 56.

- ^ Neusner 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Bauckham 2015, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Van der Watt 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Moloney 1998, p. 4.

- ^ a b Watson 2014, p. 112.

- ^ Sanders 1995, pp. 57, 70–71.

- ^ Theissen & Merz 1998, pp. 36–37.

Bibliography[edit]

- Attridge, Harold W. (2006). "The Literary Evidence for Johannine Christianity". In Mitchell, Margaret M.; Young, Frances M.; Bowie, K. Scott (eds.). Cambridge History of Christianity. Volume 1, Origins to Constantine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521812399.

- Aune, David E. (2003). "John, Gospel of". The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early Christian Literature and Rhetoric. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-21917-8.

- Barrett, C. K. (1978). The Gospel According to St. John: An Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22180-5.

- Barton, Stephen C. (2008). Bauckham, Richard; Mosser, Carl (eds.). The Gospel of John and Christian Theology. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802827173.

- Bauckham, Richard (2008). "The Fourth Gospel as the Testimony of the Beloved Disciple". In Bauckham, Richard; Mosser, Carl (eds.). The Gospel of John and Christian Theology. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802827173.

- Bauckham, Richard (2007). The Testimony of the Beloved Disciple: Narrative, History, and Theology in the Gospel of John. Baker. ISBN 978-0-8010-3485-5.

- Bauckham, Richard (2015). Gospel of Glory: Major Themes in Johannine Theology. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4412-2708-9.

- Bauckham, Richard (2015). "Sacraments and the Gospel of John". In Boersma, Hans; Levering, Matthew (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Sacramental Theology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191634185.

- Blomberg, Craig (2011). The Historical Reliability of John's Gospel. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-3871-4.

- Bourgel, Jonathan (2018). "John 4 : 4–42: Defining A Modus Vivendi Between Jews And The Samaritans". Journal of Theological Studies. 69 (1): 39–65. doi:10.1093/jts/flx215.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1966). The Gospel According to John, Volume 1. Anchor Bible series. 29. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-01517-2.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1997). An Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Anchor Bible. ISBN 0-385-24767-2.

- Burge, Gary M. (2014). "Gospel of John". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-72224-3.

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.

- Bynum, Wm. Randolph (2012). The Fourth Gospel and the Scriptures: Illuminating the Form and Meaning of Scriptural Citation in John 19:37. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004228436.

- Carson, D. A. (1991). The Pillar New Testament Commentary: The Gospel According to John. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eardmans.

- Carson, D. A.; Moo, Douglas J. (2009). An Introduction to the New Testament. HarperCollins Christian Publishing. ISBN 978-0-310-53955-1.

- Charlesworth, James (2010). "The Historical Jesus in the Fourth Gospel: A Paradigm Shift?" (PDF). Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus. 8 (1): 3–46. doi:10.1163/174551909X12607965419559. ISSN 1476-8690.

- Chilton, Bruce; Neusner, Jacob (2006). Judaism in the New Testament: Practices and Beliefs. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-81497-8.

- Combs, William W. (1987). "Nag Hammadi, Gnosticism and New Testament Interpretation". Grace Theological Journal. 8 (2): 195–212. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Culpepper, R. Alan (2011). The Gospel and Letters of John. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426750052.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005). "John, Gospel of St.". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- DeConick, April D (2016). "Who is Hiding in the Gospel of John? Reconceptualizing Johannine Theology and the Roots of Gnosticism". In DeConick, April D; Adamson, Grant (eds.). Histories of the Hidden God: Concealment and Revelation in Western Gnostic, Esoteric, and Mystical Traditions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-93599-4.

- Denaux, Adelbert (1992). "The Q-Logion Mt 11, 27 / Lk 10, 22 and the Gospel of John". In Denaux, Adelbert (ed.). John and the Synoptics. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium. 101. Leuven University Press. pp. 113–47. ISBN 978-90-6186-498-1.

- Dunn, James D. G. (1992). The Question of Anti-Semitism in the New Testament. ISBN 978-0-8028-4498-9.

- Edwards, Ruth B. (2015). Discovering John: Content, Interpretation, Reception. Discovering Biblical Texts. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-7240-1.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1996). The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974628-6.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2009). Jesus, Interrupted. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-117393-6.

- Eve, Eric (2016). Writing the Gospels: Composition and Memory. SPCK. ISBN 9780281073412.

- Fredriksen, Paula (2008). From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16410-7.

- Funk, Robert Walter; Hoover, Roy W. (1993). The Five Gospels: The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus : New Translation and Commentary. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-541949-0 – via Jesus Seminar.

- Funk, Robert Walter (1998). The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 978-0-06-062978-6 – via Jesus Seminar.

- Greene, Colin J. D. (24 June 2004). Christology in Culture Perspective: Marking Out the Horizons. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-2792-0.

- Harris, Stephen L. (2006). Understanding the Bible (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-296548-3.

- Hendricks, Obrey M., Jr. (2007). "The Gospel According to John". In Coogan, Michael D.; Brettler, Marc Z.; Newsom, Carol A.; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible (3rd ed.). Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59856-032-9.

- Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). How on Earth Did Jesus Become a God?: Historical Questions about Earliest Devotion to Jesus. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2861-3.

- Keener, Craig S. (2019). Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels. Eerdmans. ISBN 9781467456760.

- Kelly, Joseph F. (2012). History and Heresy: How Historical Forces Can Create Doctrinal Conflicts. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814659991.

- Köstenberger, Andreas (2006). "Destruction of the Temple and the Composition of the Fourth Gospel". In Lierman, John (ed.). Challenging Perspectives on the Gospel of John. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161491139.

- Köstenberger, Andreas (2013). Encountering John. Baker Academic. ISBN 9781441244857.

- Köstenberger, Andreas J. (2015). A Theology of John's Gospel and Letters: The Word, the Christ, the Son of God. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-52326-0.

- Kovacs, Judith L. (1995). "Now Shall the Ruler of This World Be Driven Out: Jesus' Death as Cosmic Battle in John 12:20–36". Journal of Biblical Literature. 114 (2): 227–47. doi:10.2307/3266937. JSTOR 3266937.

- Kruse, Colin G. (2004). The Gospel According to John: An Introduction and Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802827715.

- Kysar, Robert (2005). Voyages with John: Charting the Fourth Gospel. Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-932792-43-0.

- Kysar, Robert (2007). John, the Maverick Gospel. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. ISBN 9780664230562.

- Kysar, Robert (2007). "The Dehistoricizing of the Gospel of John". In Anderson, Paul N.; Just, Felix; Thatcher, Tom (eds.). John, Jesus, and History, Volume 1: Critical Appraisals of Critical Views. Society of Biblical Literature Symposium series. 44. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-293-0.

- Ladd, George Eldon; Hagner, Donald Alfred (1993). A Theology of the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-0680-5.

- Lamb, David A. (2014). Text, Context and the Johannine Community: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Johannine Writings. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567129666.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2005). Gospel According to St John: Black's New Testament Commentaries. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-8822-9.

- Lindars, Barnabas (1990). John. New Testament Guides. 4. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85075-255-4.

- Lindars, Barnabas; Edwards, Ruth; Court, John M. (2000). The Johannine Literature. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-081-4.

- Llewelyn, Stephen Robert; Robinson, Alexandra; Wassell, Blake Edward (2018). "Does John 8:44 Imply That the Devil Has a Father?". Novum Testamentum. 60 (1): 14–23. doi:10.1163/15685365-12341587. ISSN 0048-1009.

- Martin, Dale B. (2012). New Testament History and Literature. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300182194.

- Menken, M.J.J. (1996). Old Testament Quotations in the Fourth Gospel: Studies in Textual Form. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789039001813.

- Metzger, B. M.; Ehrman, B. D. (1985). The Text of New Testament. Рипол Классик. ISBN 978-5-88500-901-0.

- Michaels, J. Ramsey (1971). "Verification of Jesus' Self-Revelation in His passion and Resurrection (18:1–21:25)". The Gospel of John. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4674-2330-4.

- Moloney, Francis J. (1998). The Gospel of John. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5806-2.

- Most, Glenn W. (2005). Doubting Thomas. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01914-0.

- Moule, C. F. D. (July 1962). "The Individualism of the Fourth Gospel". Novum Testamentum. 5 (2/3): 171–90. doi:10.2307/1560025. JSTOR 1560025.

- Neusner, Jacob (2003). Invitation to the Talmud: A Teaching Book. South Florida Studies in the History of Judaism. 169. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59244-155-6.

- O'Day, Gail R. (1998). "John". In Newsom, Carol Ann; Ringe, Sharon H. (eds.). Women's Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664257811.

- Olson, Roger E. (1999). The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition & Reform. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1505-0.

- Pagels, Elaine H. (2003). Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50156-8.

- Perkins, Pheme (1993). Gnosticism and the New Testament. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451415971.

- Porter, Stanley E. (2015). John, His Gospel, and Jesus: In Pursuit of the Johannine Voice. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-7170-1.

- Porter, Stanley E.; Fay, Ron C. (2018). "Introduction". In Porter, Stanley E.; Fay, Ron C. (eds.). The Gospel of John in Modern Interpretation. Kregel Academic. ISBN 9780825445101.

- Reddish, Mitchell G. (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426750083.

- Reinhartz, Adele (2017). "The Gospel According to John". In Levine, Amy-Jill; Brettler, Marc Z. (eds.). The Jewish Annotated New Testament (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190461850.

- Ronning, John L. (2010). The Jewish Targums and John's Logos Theology. Hendrickson. ISBN 978-1-59856-306-1.

- Sanders, E. P. (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7.

- Senior, Donald (1991). The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of John. Passion of Jesus Series. 4. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5462-0.

- Skarsaune, Oskar (2008). In the Shadow of the Temple: Jewish Influences on Early Christianity. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2670-4.

- Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998) [1996]. The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-0863-8.

- Thompson, Marianne Maye (2006). "The Gospel According to John". In Barton, Stephen C. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels. Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80766-1.

- Tuckett, Christopher M. (2003). "Introduction to the Gospels". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

- Valantasis, Richard; Bleyle, Douglas K.; Haugh, Dennis C. (2009). The Gospels and Christian Life in History and Practice. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742570696.

- Van den Broek, Roelof; Vermaseren, Maarten Jozef (1981). Studies in Gnosticism and Hellenistic Religions. Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain. 91. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-06376-1.

- Van der Watt, Jan (2008). An Introduction to the Johannine Gospel and Letters. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-52174-3.

- Walvoord, John F.; Zuck, Roy B, eds. (1985). The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures. David C Cook. ISBN 978-0-88207-813-7.*Watson, Duane (2014). "Christology". In Evans, Craig (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN 9781317722243.

- Williamson, Lamar, Jr. (2004). Preaching the Gospel of John: Proclaiming the Living Word. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22533-9.

- Witherington, Ben (2004). The New Testament Story. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2765-4.

- Yu Chui Siang Lau, Theresa (2010). "The Gospels and the Old Testament". In Harding, Mark; Nobbs, Alanna (eds.). The Content and the Setting of the Gospel Tradition. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802833181.

- Zimmermann, Ruben (2015). Puzzling the Parables of Jesus: Methods and Interpretation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-6532-7.

External links[edit]

Online translations of the Gospel of John:

- Over 200 versions in over 70 languages at Bible Gateway

- The Unbound Bible from Biola University

- David Robert Palmer, Translation from the Greek

- Text of the Gospel with textual variants

- The Egerton Gospel text; compare with Gospel of John

Gospel of John | ||

| Preceded by Gospel of Luke | New Testament Books of the Bible | Succeeded by Acts of the Apostles |