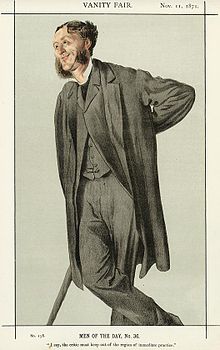

Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold | |

|---|---|

Matthew Arnold, by Elliott & Fry, circa 1883. | |

| Born | 24 December 1822 Laleham, England |

| Died | 15 April 1888 (aged 65) Liverpool, England |

| Occupation | Her Majesty's Inspector of Schools |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | Victorian |

| Genre | Poetry; literary, social and religious criticism |

| Notable works | "Dover Beach", "The Scholar-Gipsy", "Thyrsis", Culture and Anarchy, Literature and Dogma , "The Study of Poetry." |

| Spouse | Frances Lucy |

| Children | 6 |

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the celebrated headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, literary professor, and William Delafield Arnold, novelist and colonial administrator.

Matthew Arnold has been characterised as a sage writer, a type of writer who chastises and instructs the reader on contemporary social issues.[1]

He was also an inspector of schools for thirty-five years, and supported the concept of state-regulated secondary education.[2]

Early years[edit source]

He was the eldest son of Thomas Arnold and his wife Mary Penrose Arnold (1791–1873), born on 24 December 1822 at Laleham-on-Thames, Middlesex.[3] John Keble stood as godfather to Matthew.

In 1828, Thomas Arnold was appointed Headmaster of Rugby School, where the family took up residence, that year. From 1831, Arnold was tutored by his clerical uncle, John Buckland, in Laleham. In 1834, the Arnolds occupied a holiday home, Fox How, in the Lake District. There William Wordsworth was a neighbour and close friend.

In 1836, Arnold was sent to Winchester College, but in 1837 he returned to Rugby School. He moved to the sixth form in 1838 and so came under the direct tutelage of his father. He wrote verse for a family magazine, and won school prizes, His prize poem, "Alaric at Rome", was printed at Rugby.

In November 1840, aged 17, Arnold matriculated at Balliol College, Oxford, where in 1841 he won an open scholarship, graduating B.A. in 1844.[3][4] During his student years at Oxford, his friendship became stronger with Arthur Hugh Clough, a Rugby pupil who had been one of his father's favourites. He attended John Henry Newman's sermons at the University Church of St Mary the Virgin but did not join the Oxford Movement. His father died suddenly of heart disease in 1842, and Fox How became the family's permanent residence. His poem Cromwell won the 1843 Newdigate prize.[5] He graduated in the following year with second class honours in Literae Humaniores.

In 1845, after a short interlude of teaching at Rugby, Arnold was elected Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford. In 1847, he became Private Secretary to Lord Lansdowne, Lord President of the Council. In 1849, he published his first book of poetry, The Strayed Reveller. In 1850 Wordsworth died; Arnold published his "Memorial Verses" on the older poet in Fraser's Magazine.

Marriage and career[edit source]

Wishing to marry but unable to support a family on the wages of a private secretary, Arnold sought the position of and was appointed in April 1851 one of Her Majesty's Inspectors of Schools. Two months later, he married Frances Lucy, daughter of Sir William Wightman, Justice of the Queen's Bench.

Arnold often described his duties as a school inspector as "drudgery" although "at other times he acknowledged the benefit of regular work."[6] The inspectorship required him, at least at first, to travel constantly and across much of England. "Initially, Arnold was responsible for inspecting Nonconformist schools across a broad swath of central England. He spent many dreary hours during the 1850s in railway waiting-rooms and small-town hotels, and longer hours still in listening to children reciting their lessons and parents reciting their grievances. But that also meant that he, among the first generation of the railway age, travelled across more of England than any man of letters had ever done. Although his duties were later confined to a smaller area, Arnold knew the society of provincial England better than most of the metropolitan authors and politicians of the day."[7]

Literary career[edit source]

In 1852, Arnold published his second volume of poems, Empedocles on Etna, and Other Poems. In 1853, he published Poems: A New Edition, a selection from the two earlier volumes famously excluding Empedocles on Etna, but adding new poems, Sohrab and Rustum and The Scholar Gipsy. In 1854, Poems: Second Series appeared; also a selection, it included the new poem, Balder Dead.

Arnold was elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford in 1857, and he was the first in this position to deliver his lectures in English rather than in Latin.[8] He was re-elected in 1862. On Translating Homer (1861) and the initial thoughts that Arnold would transform into Culture and Anarchy were among the fruits of the Oxford lectures. In 1859, he conducted the first of three trips to the continent at the behest of parliament to study European educational practices. He self-published The Popular Education of France (1861), the introduction to which was later published under the title Democracy (1879).[9]

In 1865, Arnold published Essays in Criticism: First Series. Essays in Criticism: Second Series would not appear until November 1888, shortly after his untimely death. In 1866, he published Thyrsis, his elegy to Clough who had died in 1861. Culture and Anarchy, Arnold's major work in social criticism (and one of the few pieces of his prose work currently in print) was published in 1869. Literature and Dogma, Arnold's major work in religious criticism appeared in 1873. In 1883 and 1884, Arnold toured the United States and Canada[10] delivering lectures on education, democracy and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1883.[11] In 1886, he retired from school inspection and made another trip to America. An edition of Poems by Matthew Arnold, with an introduction by A. C. Benson and illustrations by Henry Ospovat, was published in 1900 by John Lane.[12]

Death[edit source]

Arnold died suddenly in 1888 of heart failure whilst running to meet a train that would have taken him to the Liverpool Landing Stage to see his daughter, who was visiting from the United States where she had moved after marrying an American. He was survived by his wife, who died in June 1901.[13]

Character[edit source]

"Matthew Arnold," wrote G. W. E. Russell in Portraits of the Seventies, is "a man of the world entirely free from worldliness and a man of letters without the faintest trace of pedantry".[14] Arnold was a familiar figure at the Athenaeum Club, a frequent diner-out and guest at great country houses, charming, fond of fishing (but not of shooting),[15] and a lively conversationalist, with a self-consciously cultivated air combining foppishness and Olympian grandeur. He read constantly, widely, and deeply, and in the intervals of supporting himself and his family by the quiet drudgery of school inspecting, filled notebook after notebook with meditations of an almost monastic tone. In his writings, he often baffled and sometimes annoyed his contemporaries by the apparent contradiction between his urbane, even frivolous manner in controversy, and the "high seriousness" of his critical views and the melancholy, almost plaintive note of much of his poetry. "A voice poking fun in the wilderness" was T. H. Warren's description of him.

Poetry[edit source]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

Arnold is sometimes called the third great Victorian poet, along with Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning.[16] Arnold was keenly aware of his place in poetry. In an 1869 letter to his mother, he wrote:

Stefan Collini regards this as "an exceptionally frank, but not unjust, self-assessment. ... Arnold's poetry continues to have scholarly attention lavished upon it, in part because it seems to furnish such striking evidence for several central aspects of the intellectual history of the nineteenth century, especially the corrosion of 'Faith' by 'Doubt'. No poet, presumably, would wish to be summoned by later ages merely as an historical witness, but the sheer intellectual grasp of Arnold's verse renders it peculiarly liable to this treatment."[18]

Harold Bloom echoes Arnold's self-characterization in his introduction (as series editor) to the Modern Critical Views volume on Arnold: "Arnold got into his poetry what Tennyson and Browning scarcely needed (but absorbed anyway), the main march of mind of his time." Of his poetry, Bloom says,

Sir Edmund Chambers noted that "in a comparison between the best works of Matthew Arnold and that of his six greatest contemporaries ... the proportion of work which endures is greater in the case of Matthew Arnold than in any one of them."[20] Chambers judged Arnold's poetic vision by

His literary career — leaving out the two prize poems — had begun in 1849 with the publication of The Strayed Reveller and Other Poems by A., which attracted little notice and was soon withdrawn. It contained what is perhaps Arnold's most purely poetical poem, "The Forsaken Merman." Empedocles on Etna and Other Poems (among them "Tristram and Iseult"), published in 1852, had a similar fate. In 1858 he published his tragedy of Merope, calculated, he wrote to a friend, "rather to inaugurate my Professorship with dignity than to move deeply the present race of humans," and chiefly remarkable for some experiments in unusual – and unsuccessful – metres.

His 1867 poem "Dover Beach" depicted a nightmarish world from which the old religious verities have receded. It is sometimes held up as an early, if not the first, example of the modern sensibility. In a famous preface to a selection of the poems of William Wordsworth, Arnold identified, a little ironically, as a "Wordsworthian." The influence of Wordsworth, both in ideas and in diction, is unmistakable in Arnold's best poetry. Arnold's poem "Dover Beach" was included in Ray Bradbury's novel Fahrenheit 451, and is also featured prominently in the novel Saturday by Ian McEwan. It has also been quoted or alluded to in a variety of other contexts (see Dover Beach). Henry James wrote that Matthew Arnold's poetry will appeal to those who "like their pleasures rare" and who like to hear the poet "taking breath." In his poetry he derived not only the subject matter of his narrative poems from traditional or literary sources, and much of the romantic melancholy of his earlier poems from Senancour's "Obermann".

Prose[edit source]

Assessing the importance of Arnold's prose work in 1988, Stefan Collini stated, "for reasons to do with our own cultural preoccupations as much as with the merits of his writing, the best of his prose has a claim on us today that cannot be matched by his poetry."[22] "Certainly there may still be some readers who, vaguely recalling 'Dover Beach' or 'The Scholar Gipsy' from school anthologies, are surprised to find he 'also' wrote prose."[23]

George Watson follows George Saintsbury in dividing Arnold's career as a prose writer into three phases: 1) early literary criticism that begins with his preface to the 1853 edition of his poems and ends with the first series of Essays in Criticism (1865); 2) a prolonged middle period (overlapping the first and third phases) characterised by social, political and religious writing (roughly 1860–1875); 3) a return to literary criticism with the selecting and editing of collections of Wordsworth's and Byron's poetry and the second series of Essays in Criticism.[24] Both Watson and Saintsbury declare their preference for Arnold's literary criticism over his social or religious criticism. More recent writers, such as Collini, have shown a greater interest in his social writing,[25] while over the years a significant second tier of criticism has focused on Arnold's religious writing.[26] His writing on education has not drawn a significant critical endeavour separable from the criticism of his social writings.[27]

Selections from the Prose Work of Matthew Arnold[28]

Literary criticism[edit source]

Arnold's work as a literary critic began with the 1853 "Preface to the Poems". In it, he attempted to explain his extreme act of self-censorship in excluding the dramatic poem "Empedocles on Etna". With its emphasis on the importance of subject in poetry, on "clearness of arrangement, rigor of development, simplicity of style" learned from the Greeks, and in the strong imprint of Goethe and Wordsworth, may be observed nearly all the essential elements in his critical theory. George Watson described the preface, written by the thirty-one-year-old Arnold, as "oddly stiff and graceless when we think of the elegance of his later prose."[29]

Criticism began to take first place in Arnold's writing with his appointment in 1857 to the professorship of poetry at Oxford, which he held for two successive terms of five years. In 1861 his lectures On Translating Homer were published, to be followed in 1862 by Last Words on Translating Homer. Especially characteristic, both of his defects and his qualities, are on the one hand, Arnold's unconvincing advocacy of English hexameters and his creation of a kind of literary absolute in the "grand style," and, on the other, his keen feeling of the need for a disinterested and intelligent criticism in England.

Although Arnold's poetry received only mixed reviews and attention during his lifetime, his forays into literary criticism were more successful. Arnold is famous for introducing a methodology of literary criticism somewhere between the historicist approach common to many critics at the time and the personal essay; he often moved quickly and easily from literary subjects to political and social issues. His Essays in Criticism (1865, 1888), remains a significant influence on critics to this day, and his prefatory essay to that collection, "The Function of Criticism at the Present Time", is one of the most influential essays written on the role of the critic in identifying and elevating literature — even while admitting, "The critical power is of lower rank than the creative." Comparing himself to the French liberal essayist Ernest Renan, who sought to inculcate morality in France, Arnold saw his role as inculcating intelligence in England.[30] In one of his most famous essays on the topic, "The Study of Poetry", Arnold wrote that, "Without poetry, our science will appear incomplete; and most of what now passes with us for religion and philosophy will be replaced by poetry". He considered the most important criteria used to judge the value of a poem were "high truth" and "high seriousness". By this standard, Chaucer's Canterbury Tales did not merit Arnold's approval. Further, Arnold thought the works that had been proven to possess both "high truth" and "high seriousness", such as those of Shakespeare and Milton, could be used as a basis of comparison to determine the merit of other works of poetry. He also sought for literary criticism to remain disinterested, and said that the appreciation should be of "the object as in itself it really is."

Social criticism[edit source]

He was led on from literary criticism to a more general critique of the spirit of his age. Between 1867 and 1869 he wrote Culture and Anarchy, famous for the term he popularised for the middle class of the English Victorian era population: "Philistines", a word which derives its modern cultural meaning (in English – the German-language usage was well established) from him. Culture and Anarchy is also famous for its popularisation of the phrase "sweetness and light," first coined by Jonathan Swift.[31]

In Culture and Anarchy, Arnold identifies himself as a Liberal and "a believer in culture" and takes up what historian Richard Bellamy calls the "broadly Gladstonian effort to transform the Liberal Party into a vehicle of political moralism."[32][33] Arnold viewed with skepticism the plutocratic grasping in socioeconomic affairs, and engaged the questions which vexed many Victorian liberals on the nature of power and the state's role in moral guidance.[34] Arnold vigorously attacked the Nonconformists and the arrogance of "the great Philistine middle-class, the master force in our politics."[35] The Philistines were "humdrum people, slaves to routine, enemies to light" who believed that England's greatness was due to her material wealth alone and took little interest in culture.[35] Liberal education was essential, and by that Arnold meant a close reading and attachment to the cultural classics, coupled with critical reflection.[36] Arnold saw the "experience" and "reflection" of Liberalism as naturally leading to the ethical end of "renouncement," as evoking the "best self" to suppress one's "ordinary self."[33] Despite his quarrels with the Nonconformists, Arnold remained a loyal Liberal throughout his life, and in 1883, William Gladstone awarded him an annual pension of 250 pounds "as a public recognition of service to the poetry and literature of England."[37][38][39]

Many subsequent critics such as Edward Alexander, Lionel Trilling, George Scialabba, and Russell Jacoby have emphasized the liberal character of Arnold's thought.[40][41][42] Hugh Stuart Jones describes Arnold's work as a "liberal critique of Victorian liberalism" while Alan S. Kahan places Arnold's critique of middle-class philistinism, materialism, and mediocrity within the tradition of 'aristocratic liberalism' as exemplified by liberal thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville.[43][44]

Arnold's "want of logic and thoroughness of thought" as noted by John M. Robertson in Modern Humanists was an aspect of the inconsistency of which Arnold was accused.[45] Few of his ideas were his own, and he failed to reconcile the conflicting influences which moved him so strongly. "There are four people, in especial," he once wrote to Cardinal Newman, "from whom I am conscious of having learnt – a very different thing from merely receiving a strong impression – learnt habits, methods, ruling ideas, which are constantly with me; and the four are – Goethe, Wordsworth, Sainte-Beuve, and yourself." Dr. Arnold must be added; the son's fundamental likeness to the father was early pointed out by Swinburne, and was later attested by Matthew Arnold's grandson, Mr. Arnold Whitridge. Others such as Stefan Collini suggest that much of the criticism aimed at Arnold is based on "a convenient parody of what he is supposed to have stood for" rather than the genuine article.[33]

Journalistic criticism[edit source]

In 1887, Arnold was credited with coining the phrase "New Journalism", a term that went on to define an entire genre of newspaper history, particularly Lord Northcliffe's turn-of-the-century press empire. However, at the time, the target of Arnold's irritation was not Northcliffe, but the sensational journalism of Pall Mall Gazette editor, W.T. Stead.[46] Arnold had enjoyed a long and mutually beneficial association with the Pall Mall Gazette since its inception in 1865. As an occasional contributor, he had formed a particular friendship with its first editor, Frederick Greenwood and a close acquaintance with its second, John Morley. But he strongly disapproved of the muck-raking Stead, and declared that, under Stead, "the P.M.G., whatever may be its merits, is fast ceasing to be literature."[47]

He was appalled at the shamelessness of the sensationalistic new journalism of the sort he witnessed on his tour the United States in 1886. In his account of that tour, "Civilization in the United States", he observed, "if one were searching for the best means to efface and kill in a whole nation the discipline of self-respect, the feeling for what is elevated, he could do no better than take the American newspapers."[48]

Religious criticism[edit source]

His religious views were unusual for his time and caused sorrow to some of his best friends.[49] Scholars of Arnold's works disagree on the nature of Arnold's personal religious beliefs. Under the influence of Baruch Spinoza and his father, Dr. Thomas Arnold, he rejected the supernatural elements in religion,[50] even while retaining a fascination for church rituals. In the preface to God and the Bible, written in 1875, Arnold recounts a powerful sermon he attended discussing the "salvation by Jesus Christ", he writes: "Never let us deny to this story power and pathos, or treat with hostility ideas which have entered so deep into the life of Christendom. But the story is not true; it never really happened".[51]

He continues to express his concern with Biblical truth explaining that "The personages of the Christian heaven and their conversations are no more matter of fact than the personages of the Greek Olympus and their conversations."[51] He also wrote in Literature and Dogma: "The word 'God' is used in most cases as by no means a term of science or exact knowledge, but a term of poetry and eloquence, a term thrown out, so to speak, as a not fully grasped object of the speaker's consciousness – a literary term, in short; and mankind mean different things by it as their consciousness differs."[52] He defined religion as "morality touched with emotion".[53]

However, he also wrote in the same book, "to pass from a Christianity relying on its miracles to a Christianity relying on its natural truth is a great change. It can only be brought about by those whose attachment to Christianity is such, that they cannot part with it, and yet cannot but deal with it sincerely."[54]

Reputation[edit source]

Harold Bloom writes that "Whatever his achievement as a critic of literature, society or religion, his work as a poet may not merit the reputation it has continued to hold in the twentieth century. Arnold is, at his best, a very good, but highly derivative poet, unlike Tennyson, Browning, Hopkins, Swinburne and Rossetti, all of whom individualized their voices."[55]

The writer John Cowper Powys, an admirer, wrote that, "with the possible exception of Merope, Matthew Arnold's poetry is arresting from cover to cover – [he] is the great amateur of English poetry [he] always has the air of an ironic and urbane scholar chatting freely, perhaps a little indiscreetly, with his not very respectful pupils."[56]

Family[edit source]

The Arnolds had six children: Thomas (1852–1868); Trevenen William (1853–1872); Richard Penrose (1855–1908), an inspector of factories;[note 1] Lucy Charlotte (1858–1934) who married Frederick W. Whitridge of New York, whom she had met during Arnold's American lecture tour; Eleanore Mary Caroline (1861–1936) married (1) Hon. Armine Wodehouse (MP) in 1889, (2) William Mansfield, 1st Viscount Sandhurst, in 1909; Basil Francis (1866–1868).

Selected bibliography[edit source]

Poetry[edit source]

- Stanzas in Memory of the Author of "Obermann" (1849)

- The Strayed Reveller, and Other Poems (1849)

- Empedocles on Etna, and Other Poems (1852)

- Sohrab and Rustum (1853)

- The Scholar-Gipsy (1853)

- Stanzas from the Grande Chartreuse (1855)

- Memorial Verses to Wordsworth

- Rugby Chapel (1867)

- Thyrsis (1865)

Prose[edit source]

- Essays in Criticism (1865, 1888)

- Culture and Anarchy (1869)

- Friendship's Garland (1871)

- Literature and Dogma (1873)

- God and the Bible (1875)

See also[edit source]

Notes[edit source]

- ^ Composer Edward Elgar dedicated one of the Enigma Variations to Richard.

References[edit source]

Citations[edit source]

- ^ Landow, George. Elegant Jeremiahs: The Sage from Carlyle to Mailer. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1986.

- ^ Oxford illustrated encyclopedia. Judge, Harry George., Toyne, Anthony. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. 1985–1993. p. 22. ISBN 0-19-869129-7. OCLC 11814265.

- ^ a b Collini, Stefan. "Arnold, Matthew". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/679. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Foster, Joseph (1888–1892). . Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715–1886. Oxford: Parker and Co – via Wikisource.

- ^ Cromwell: A Prize Poem, Recited in the Theatre, Oxford; June 28, 1843 at Google Books

- ^ Collini, 1988, p. 21.

- ^ Collini, 1988, p. 21

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ Super, CPW, II, p. 330.

- ^ "Literary Gossip". The Week : A Canadian Journal of Politics, Literature, Science and Arts. 1. 1: 13. 6 December 1883.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ Poems by Matthew Arnold. London: John Lane. 1900. pp. xxxiv+375; with an introduction by A. C. Benson; illustrated by Henry Ospovat

- ^ "Obituary – Mrs. Matthew Arnold". The Times (36495). London. 1 July 1901. p. 11.

- ^ Russell, 1916[page needed]

- ^ Andrew Carnegie described him as the most charming man that he ever knew (Autobiography, p 298) and said, "Arnold visited us in Scotland in 1887, and talking one day of sport he said he did not shoot, he could not kill anything that had wings and could soar in the clear blue sky; but, he added, he could not give up fishing — 'the accessories are so delightful.'" Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie, The Riverside Press Cambridge (1920), p 301; https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17976

- ^ Collini, 1988, p. 2.

- ^ Lang, Volume 3, p. 347.

- ^ Collini, 1988, p. 26.

- ^ Bloom, 1987, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Chambers, 1933, p. 159.

- ^ Chambers, 1933, p. 165.

- ^ Collini, 1988, p. vii.

- ^ Collini, 1988, p. 25.

- ^ Watson, 1962, pp. 150–160. Saintsbury, 1899, p. 78 passim.

- ^ Collini, 1988. Also see the introduction to Culture and Anarchy and other writings, Collini, 1993.

- ^ See "The Critical Reception of Arnold's Religious Writings" in Mazzeno, 1999.

- ^ Mazzeno, 1999.

- ^ Arnold, Matthew (1913). William S. Johnson (ed.). Selections from the Prose Work of Matthew Arnold. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9781414233802.

- ^ Watson, 1962, p. 147.

- ^ Machann, C (1998). Matthew Arnold: A Literary Life. Springer. pp. 45–61.

- ^ The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition. Sweetness and light. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^ Born, Daniel (1995). The Birth of Liberal Guilt in the English Novel: Charles Dickens to H.G. Wells. UNC Press Books. p. 165.

- ^ a b c Caufield, James Walter (2016). Overcoming Matthew Arnold: Ethics in Culture and Criticism. Routledge. pp. 3–7.

- ^ Malachuk, D. (2005). Perfection, the State, and Victorian Liberalism. Springer. pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Brendan A. Rapple (2017). Matthew Arnold and English Education: The Poet's Pioneering Advocacy in Middle Class Instruction. McFarland. pp. 98–99.

- ^ Brendan A. Rapple (2017). Matthew Arnold and English Education: The Poet's Pioneering Advocacy in Middle Class Instruction. McFarland. p. 116. ISBN 9781476663593.

- ^ Machann, C (1998). Matthew Arnold: A Literary Life. Springer. p. 19.

- ^ Bush, Douglas (1971). Matthew Arnold: A Survey of His Poetry and Prose. Springer. p. 15.

- ^ Jones, Richard (2002). "Arnold "at Full Stretch"". Virginia Quarterly Review. 78 (2).

- ^ Jacoby, Russell (2005). Picture Imperfect: Utopian Thought for an Anti-Utopian Age. Columbia University Press. p. 67.

- ^ Alexander, Edward (2014). Matthew Arnold and John Stuart Mill. Routledge.

I have tried to show to what a considerable extent each shared the convictions of the other; how much of a liberal Arnold was and how much of a humanist Mill was.

- ^ Rodden, John (1999). Lionel Trilling and the Critics. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 215–222.

- ^ Campbell, Kate (2018). Matthew Arnold. Oxford University Press. p. 93.

- ^ Kahan, Alan S. (2012). "Arnold, Nietzsche and the Aristocratic Vision". History of Political Thought. 33 (1): 125–143.

- ^ Robertson, John M. (1901). Modern Humanists. S. Sonnenschein. p. 145.

If, then, a man come to the criticism of life as Arnold did, with neither a faculty nor a training for logic ... it is impossible that he should escape frequent error or inconsistency ...

- ^ We have had opportunities of observing a new journalism which a clever and energetic man has lately invented. It has much to recommend it; it is full of ability, novelty, variety, sensation, sympathy, generous instincts; its one great fault is that it is feather-brained." Mathew Arnold, The Nineteenth century No. CXXIII. (May 1887) pp. 629–643. Available online at attackingthedevil.co.uk

- ^ Quoted in Harold Begbie, The Life of General William Booth Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, (2 vols., New York, 1920). Available [online]

- ^ Gurstein, Rochelle (2016). The Repeal of Reticence: America's Cultural and Legal Struggles Over Free Speech, Obscenity, Sexual Liberation, and Modern Art. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 57–58.

- ^ When visiting the grave of his godfather, Bishop Keble, in about 1880 with Andrew Carnegie, he said 'Ah, dear, dear Keble! I caused him much sorrow by my views upon theological subjects, which caused me sorrow also, but notwithstanding he was deeply grieved, dear friend as he was, he travelled to Oxford and voted for me for Professor of English Poetry.' "Later the subject of his theological views was referred to. He said they had caused sorrow to his best friends."Mr. Gladstone once gave expression to his deep disappointment, or to something like displeasure, saying I ought to have been a bishop. No doubt my writings prevented my promotion, as well as grieved my friends, but I could not help it. I had to express my views." Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie, The Riverside Press Cambridge (1920), p 298; https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17976

- ^ Andrew Carnegie, who knew and admired him, said Arnold was a "seriously religious man ... No irreverent word ever escaped his lips ... and yet he had in one short sentence slain the supernatural. 'The case against miracles is closed. They do not happen.'". Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie, The Riverside Press Cambridge (1920), p 299; https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17976

- ^ a b Super, CPW, VII, p. 384.

- ^ Super, CPW, VI, p. 171.

- ^ Super, CPW, VI, p. 176.

- ^ Super, CPW, VI, p. 143.

- ^ Poets and Poems, Harold Bloom, p. 203.

- ^ The Pleasures of Literature, John Cowper Powys, pp. 397–398.

Abbreviation: CPW stands for Robert H. Super (editor), The Complete Prose Works of Matthew Arnold, see Bibliography.

Sources[edit source]

- Primary sources

- George W. E. Russell (editor), Letters of Matthew Arnold, 1849–88, 2 vols. (London and New York: Macmillan, 1895)

- Published seven years after their author's death these letters were heavily edited by Arnold's family.

- Howard F. Lowry (editor), The Letters of Matthew Arnold to Arthur Hugh Clough (New York: Oxford University Press, 1932)

- C. B. Tinker and H. F. Lowry (editors), The Poetical Works of Matthew Arnold, Oxford University Press, 1950 standard edition, OCLC 556893161

- Kenneth Allott (editor), The Poems of Matthew Arnold (London and New York: Longman Norton, 1965) ISBN 0-393-04377-0

- Part of the "Annotated English Poets Series," Allott includes 145 poems (with fragments and juvenilia) all fully annotated.

- Robert H. Super (editor), The Complete Prose Works of Matthew Arnold in eleven volumes (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1960–1977)

- Miriam Allott and Robert H. Super (editors), The Oxford Authors: Matthew Arnold (Oxford: Oxford university Press, 1986)

- A strong selection from Miriam Allot, who had (silently) assisted her husband in editing the Longman Norton annotated edition of Arnold's poems, and Robert H. Super, editor of the eleven volume complete prose.

- Stefan Collini (editor), Culture and Anarchy and other writings (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993) part of the Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought series.

- Collini's introduction to this edition attempts to show that "Culture and Anarchy, first published in 1869, has left a lasting impress upon subsequent debate about the relation between politics and culture" —Introduction, p. ix.

- Cecil Y. Lang (editor), The Letters of Matthew Arnold in six volumes (Charlottesville and London: The University Press of Virginia, 1996–2001)

- Biographies (by publication date)

- George Saintsbury, Matthew Arnold (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1899)

- Saintsbury combines biography with critical appraisal. In his view, "Arnold's greatness lies in 'his general literary position' (p. 227). Neither the greatest poet nor the greatest critic, Arnold was able to achieve distinction in both areas, making his contributions to literature greater than those of virtually any other writer before him." Mazzeno, 1999, p. 8.

- Herbert W. Paul, Mathew Arnold (London: Macmillan, 1902)

- G. W. E. Russell, Matthew Arnold (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1904)

- Lionel Trilling, Matthew Arnold (New York: Norton, 1939)

- Trilling called his study a "biography of a mind."

- Park Honan, Matthew Arnold, a life (New York, McGraw–Hill, 1981) ISBN 0-07-029697-9

- "Trilling's book challenged and delighted me but failed to take me close to Matthew Arnold's life. ... I decided in 1970 to write a definitive biography ... Three-quarters of the biographical data in this book, I may say, has not appeared in a previous study of Arnold." —Preface, pp. viii–ix.

- Stefan Collini, Arnold (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988)

- A good starting point for those new to Arnold's prose. "Like many late century scholars, Collini believes Arnold's chief contribution to English literature is as a critic. ... Collini insists Arnold remains a force in literary criticism because 'he characterizes in unforgettable ways' the role that literary and cultural criticism 'can and must play in modern societies'" (p. 67). Mazzeno, 1999, pp. 103–104.

- Nicholas Murray, A Life of Matthew Arnold (New York: St. Martin's, 1996)

- "...focuses on the conflicts between Arnold's public and private lives. A poet himself, Murray believes Arnold was a superb poet who turned to criticism when he realised his gift for verse was fading." Mazzeno, 1999, p. 118.

- Ian Hamilton, A Gift Imprisoned: A Poetic Life of Matthew Arnold (London: Bloomsbury, 1998)

- "Choosing to concentrate on the development of Arnold's talents as a poet, Hamilton takes great pains to explore the biographical and literary sources of Arnold's verse." Mazzeno, 1999, p. 118.

- Bibliography

- Thomas Burnett Smart, The Bibliography of Matthew Arnold 1892, (reprinted New York: Burt Franklin, 1968, Burt Franklin Bibliography and Reference Series #159)

- Laurence W. Mazzeno, Matthew Arnold: The Critical Legacy (Woodbridge: Camden House, 1999)

- Not a true bibliography, nonetheless, it provides thorough coverage and intelligent commentary for the critical writings on Arnold.

- Writings on Matthew Arnold or containing significant discussion of Arnold (by publication date)

- Stephen, Leslie (1898). "Matthew Arnold". Studies of a Biographer. 2. London: Duckworth and Co. pp. 76–122.

- G. W. E. Russell, Portraits of the Seventies (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916)

- Sir Edmund Chambers, "Matthew Arnold," Watson Lecture on English Poetry, 1932, in English Critical Essays: Twentieth century, Phyllis M. Jones (editor) (London: Oxford University Press, 1933)

- T. S. Eliot, "Matthew Arnold" in The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1933)

- This is Eliot's second essay on Matthew Arnold. The title of the series consciously echoes Arnold's essay, "The Function of Criticism at the Present Time" (1864).

- Professors Chauncey Brewster Tinker and Howard Foster Lowry, The Poetry of Matthew Arnold: A Commentary (New York: Oxford University Press, 1940) Alibris ID 8235403151

- W. F. Connell, The Educational Thought and Influence of Matthew Arnold (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd, 1950)

- Mazzeno describes this as the "definitive word" on Arnold's educational thought. Mazzeno, 1999, p. 42.

- George Watson, "Matthew Arnold" in The Literary Critics: A Study of English Descriptive Criticism (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1962)

- A. Dwight Culler, "Imaginative Reason: The Poetry of Matthew Arnold" (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966).

- Described by Stefan Collini as "the most comprehensive discussion" of the poetry in his "Arnold" Past Masters, p. 121.

- David J. DeLaura, "Hebrew and Hellene in Victorian England: Newman, Arnold, and Pater" (Austin: University of Texas Pr, 1969).

- This celebrated study brilliantly situates Arnold in the intellectual history of his time.

- Northrop Frye, The Critical Path: An Essay on the Social Context of Literary Criticism (in "Daedalus", 99, 2, pp. 268–342, Spring 1970; then New York: Prentice Hall/Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1983) ISBN 0-7108-0641-8

- Joseph Carroll, The Cultural Theory of Matthew Arnold. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981)

- Ruth apRoberts, Arnold and God (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983)

- Harold Bloom (editor), W. H. Auden, J. Hillis Miller, Geoffrey Tillotson, G. Wilson Knight, William Robbins, William E. Buckler, Ruth apRoberts, A. Dwight Culler, and Sara Suleri, Modern Critical Views: Matthew Arnold (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1987)

- David G. Riede, Matthew Arnold and the Betrayal of Language (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988)

- "...explores Arnold's attempts to find an authoratative language, and argues that his occasional claims for such language reveal more uneasiness than confidence in the value of 'letters.' ... Riede argues that Arnold's determined efforts to write with authority, combined with his deep-seated suspicion of his medium, result in an exciting if often agonised tension in his poetic language." –from the book flap.

- Donald Stone, Communications with the Future: Matthew Arnold in Dialogue (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997)

- Linda Ray Pratt, Matthew Arnold Revisited, (New York: Twayne Publishers, 2000) ISBN 0-8057-1698-X

- Francesco Marroni, Miti e mondi vittoriani (Rome: Carocci, 2004)

- Renzo D'Agnillo, The Poetry of Matthew Arnold (Rome: Aracne, 2005)

External links[edit source]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Matthew Arnold. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Matthew Arnold |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Matthew Arnold |

- Portraits of Matthew Arnold at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- "MATTHEW ARNOLD (Obituary Notice, Tuesday, April 17, 1888)". Eminent Persons: Biographies reprinted from The Times. IV (1887-1890). London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. 1893. pp. 87-96. Retrieved 12 March 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Works by Matthew Arnold at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Matthew Arnold at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Matthew Arnold at Internet Archive

- Works by Matthew Arnold at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Full text of 'The Function of Criticism at the Present Time' at The Fortnightly Review.

- Poetry of Matthew Arnold at Poetseers

- Matthew Arnold, by G. W. E. Russell, at Project Gutenberg

- The Letters of Matthew Arnold Digital Edition, at the University of Virginia Press

- "Archival material relating to Matthew Arnold". UK National Archives.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.- A Bibliography of the Works of Matthew Arnold by Tod E. Jones

- Plaque #38 on Open Plaques

- Anonymous (1873). Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day. Illustrated by Frederick Waddy. London: Tinsley Brothers. pp. 136–37. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- Matthew Arnold at University of Toronto Libraries

- Literature and Science (1882)

- Mathew Arnold Letters and Works at Texas Tech University Libraries

- Matthew Arnold Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.