Tara Brach on Mindfulness, Psychotherapy and Awakening

by Deb Kory

Buddhist meditation teacher and clinical psychologist, Tara Brach, PhD, discusses her evolution as a clinical psychologist and spiritual teacher, the painful illness that inspired her latest book, her commitment to help heal the planet and to love life—no matter what.

FILED UNDER: Integrative, Mindfulness, Jon Kabat-Zinn, Eating Disorders, Trauma/PTSD

Earn CE Credit

IN THIS INTERVIEW…

What is Mindfulness

Meditation and Psychotherapy

The Alive Zone

The Trance of Bad Personhood

Will This Serve?

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love

The Squeeze

No Mud, No Lotus

Awakening to the World's Suffering

RAIN

Click here to visit our new Coping with COVID-19 page to get free videos and other resources to help you help your clients during this time.

What is Mindfulness

DEB KORY: In this day and age a lot of people are throwing around the term mindfulness. Many therapists—particularly in the Bay Area—describe their approach as “mindfulness-based,” but I have a feeling that most people don't actually know what that means. What exactly is mindfulness? What does it mean to be a mindfulness-based therapist?

TARA BRACH:

Mindfulness is a way of paying attention moment-to-moment to what's happening within and around us without judgment.Mindfulness is a way of paying attention moment-to-moment to what's happening within and around us without judgment. So, said differently, when we attend to the moment-to-moment flow of experience, and recognize what's happening…fully allowing it, not adding judgment or commentary, then we are cultivating a mindful awareness.

DK: So, it's non-judgmental awareness of the present moment?

TB: That's another way to say it, yes.

DK: How does that relate to being a mindfulness-based psychotherapist? What does that mean?

TB: It means that intrinsic to the psychotherapy is a valuing of cultivating that kind of attention, and an encouragement of the person you're working with to cultivate it, and a use of it yourself. It can be sometimes formally woven into the therapy, but sometimes it's just implicit.

Meditation and Psychotherapy

DK: Where does meditation come in? Is that a necessary part of mindfulness work?

TB: Meditation is the deliberate training of attention. So, when you do a mindfulness meditation, you are deliberately cultivating mindfulness by using strategies to enter the present moment and to let go of judgment and so on.

DK: So, it's a way to help cultivate awareness of the present moment, and I would imagine that's especially important for therapists. Does that mean that you actually do meditation in your sessions with people?

TB: Well, some people do, and some people don't. I'm not in active clinical practice right now. I was, for several decades, seeing clients regularly and then turned to mostly writing and teaching and training therapists in how to weave mindfulness into their practice. So, I'm no longer seeing clients myself, but when I did see clients and when I work with people and do sessions that are related to meditation training—I would often, as part of a process of them getting in touch with what was going on inside them, invite them to pause and just simply use a period of time to quiet the mind, to just notice the changing flow of experience, or maybe to do a particular compassion practice. So, I would weave particular styles of meditation into a therapy session.

DK: Would you suggest that people do it in their day-to-day lives also?

TB: It very much depends on the client that you're working with. For some people, talking about meditation, suggesting that they meditate, is a set-up for failure and shame. They'll try to comply because they think, "Oh, Tara is this well known meditation teacher and this is what she's into, so I should do it," and so on; whereas it's not a fit for them at that particular time.

Many therapists already, just by the nature of who they are, have a natural sense of coming into presence and a deep sensitivity to other people, but all of us get help by training.

So there were many people I would see where it would be much more of an implicit part of the process. I'd be encouraging attention to what was going on in the moment, encouraging them to just notice their experience without adding any story—all things that we would associate with meditation practice without saying, "Hey, we're meditating." What makes meditation meditation is that it's an intentional process of paying attention on purpose to the present moment.

DK: And it doesn't necessarily mean sitting in the lotus pose, right? It's something that you can do in your daily life walking out in the world?

TB: Absolutely. Meditation is a training of attention that you can do in any posture, at any moment, doing anything that you're doing on the planet. In fact, for us to have the fruits of meditation, we have to be able to take it out of a compartment or a particular context and have it just be, you know, here's Deborah and Tara doing a Skype call. So, we're not leaving meditation behind just because we're in the midst of an activity.

DK: Thanks, that helps me relax a little bit!

TB: Yeah, it helps to name what we're doing. I think psychotherapy and meditation are incredibly synergistic and they fill in for each other in some important domains. There are many things that come up when we're meditating that we really actually don't have the resilience or the focus to untangle, and a therapist can help us do that. The relationship itself, a trusting respectful relationship, creates a sense of safety that can enable us to unpack things that we might not be able to work on when we're on our own, especially if there's trauma.

There are increasing numbers of people who are recognizing they have trauma in their bodies, and when they start to meditate and feel like they're kind of coming close to that, they can get flooded, overwhelmed.There are increasing numbers of people who are recognizing they have trauma in their bodies, and when they start to meditate and feel like they're kind of coming close to that, they can get flooded, overwhelmed. In therapy it's possible for people to establish safety and stability so that they can just begin to put their toe in the water and go back and forth between being with the therapist and touching into their resourcefulness and then dipping a little into the places in their body and their heart where they're feeling this more traumatic wounding. That kind of a process, if we tried it on our own just in a meditation setting, could potentially re-traumatize us.

DK: So the therapist offers a safe container for the traumatic feelings.

TB: Yes, and the relationship that really enables a person to have the support in untangling. What meditation offers to therapy is a systematic way of training the attention. Where the therapist might help a person focus and stay focused on the present moment when encountering a painful issue, meditation training teaches us to do it on our own. It builds that muscle of being able to come back to this moment, even if it connects us with something we have habitually resisted.

Meditation also trains us to, on our own, get the knack of offering ourselves compassion or forgiveness so that we can leave the therapy setting and continue in a kind of transformational way to be with the contents of our own psyche and wake up from limiting beliefs and the painful emotions.

DK: It seems at least as important for the therapist to have that ability to stay present, because there's a transmission that happens. There is an energetic quality to what we do.

TB: Exactly right. Many therapists already, just by the nature of who they are, have a natural sense of coming into presence and a deep sensitivity to other people, but all of us get help by training. All of us.

The Alive Zone

DK: One of the things I was going to ask you was about how you differentiated your roles as psychotherapist and spiritual teacher, but you’ve said you actually are no longer in clinical practice. What led to that decision to leave that particular role and go more into teaching and writing?

TB: Well, I had done clinical practice for many years and, I think, the place where I felt most needed and most alive is in the process of teaching people how to wake up their hearts and minds, and with that I mean both the practices and the whole inquiry about what really serves freedom. That realm was much more alive for me. For many, many people—most of us I'd say—meditation and therapy are incredibly juicy. They weave together beautifully. So it wasn't that I was thinking therapy wasn't an alive zone—it was just that I had put my energies really into the teaching side of things, and I was writing and that took a lot of time.

DK: Aren't there some areas of the profession that are a little bit deadening though? I'm just about to get licensed myself after an 8-year-long process, and I have been somewhat disheartened at times by the way the profession is organized—its restrictions, the whole 50-minute-hour, the billing and diagnosing, the legal and ethical structures that can at times seem very fear-based and a bit paranoid. I'm curious about what might have felt restricting to you.

TB: Well, the culture does not support the kind of processes of transformation that I'm most excited about, and they take time and immersion. I love retreat settings where people can really give themselves to a very deep attention. I like working with people when there is a longer period of time for people to be together and really have the inquiry and the experience, have the time to unfold. So, as you mentioned, with the slot of a 50-minute-hour, there's a kind of rigidity that is necessary in some ways, but not so much to my liking.

DK: In my experience—and I live in Berkeley, CA, which is considered progressive and rather “woo woo”—spirituality and religion were not incorporated into our professional training. We aren't taught to value it except in a kind of multicultural, “let’s be tolerant of other points of view” kind of way. There's an emphasis on scientific methodology, assessment, empirically validated research, etc., that feels very split off from what you’re talking about. I wonder if that was your experience at all?

TB: Well, what's alive about therapy is the therapeutic relationship and, like any other two humans connecting, nothing can really flatten that. If you know you want to show up and be with somebody and really know that you're there to see the goodness in the other person, you're there to help recognize the patterns that are getting in the way, you're there to hold a container moving through difficult material—that all is beautiful, and that can happen regardless of the structure around it.

That said, I find that I do that more effectively with people in sessions that are more focused on how to bring meditation to difficult experiences. My interest is not so much to do with coping strategies or too much emphasis on the storyline;

I'm more interested in our potential to realize the full truth of who we are beyond the story of a separate self. Most therapy is not geared in that direction.I'm more interested in our potential to realize the full truth of who we are beyond the story of a separate self. Most therapy is not geared in that direction. People that end up working with me, or working individually with me doing what I might call spiritual counseling, are kind of a self-selected group of people that are interested in a more transpersonal kind of work--not in any way to ignore the issues of the personal self, but to have the personal be a portal to the universal, and an expression of our awake heart and awareness.

DK: Where did you go to get your degree in clinical psychology?

TB: I did my undergraduate work at Clarke University, and I did my graduate degree at Fielding Institute, which is out on the West Coast in Santa Barbara.

DK: What was your plan at the time?

TB: Well, even then—I had lived in an ashram for 10 years—I was approaching psychotherapy in a very holistic way. I was doing yoga, teaching yoga, and weaving yoga and meditation into any work I did with people. So I've always been blending East and West together, right from the get-go.

My plan was to keep doing this, to be able to have a degree so I could afford to have this as a profession. I have a fascination with the psyche. I mean, I'm totally interested in how we create limiting realities about ourselves, and our capacity to see beyond the veil to the vastness and mystery of who we are. So my plan was just to keep on weaving these worlds together in whatever way would be most alive.

The Trance of Bad Personhood

DK: I read somewhere that you wrote your dissertation on eating disorders?

TB: Yeah. I had struggled with an eating disorder for a good number of years—probably 5 years—and meditation was really helpful; basically, it taught me how to pause. There's a wonderful saying that between the stimulus and the response there is a space, and in that space is our power and our freedom. That's Viktor Frankl. So the practice of meditation taught me how to pause and open mindfully to the space so that there'd be a craving or fear, but there would be some space between that and action.

It also taught me a lot about self-compassion. I found that addiction is fueled by blaming ourselves. In Buddhism, they call it “the second arrow.”

The first arrow is the craving or the fear or whatever; the second arrow is, "I'm a bad person for having these feelings or doing these behaviors."The first arrow is the craving or the fear or whatever; the second arrow is, "I'm a bad person for having these feelings or doing these behaviors." The “bad person” arrow actually locks us into the very behaviors that are causing suffering. So, in both Radical Acceptance and True Refuge, I emphasize a lot about how to wake up from that trance of bad personhood.

DK: One of the things I like about your work is that it's very integrative. I get a sense that you're really open to cognitive science, to philosophy, to various wisdom traditions, to 12-step programs—essentially to whatever seems to work for people. As someone who has benefited a great deal from the twelve-step model, I’m also well aware that it doesn’t work for everyone and that we have to have a big tool box available to help clients—particularly those struggling with powerful addictions. What’s your approach when working with addicts?

TB: Well, my inquiry is always, what have you been exploring and what helps? Humans are really resourceful, so I always try to find out what works for you. Of course, there are so many different approaches. I did my dissertation on binge-eating and meditation practice, but it became very clear to me that without having a relational component, without having a group and people to support you, nothing would hold. Whether it's a 12-step group or in the Buddhist communities we have the kalyana mitta groups, or spiritual friends groups—the great gift is that we really get that suffering is universal, that we're not alone in it, that it's not so personal, that there's hope, there are ways that we wake up out of it, and that we're there for each other. We're kind of in it together.

If there's any medicine in the whole world, it's that sense of belonging, of connection with others.If there's any medicine in the whole world, it's that sense of belonging, of connection with others.

I think that on the spiritual path, meditation—learning to be here in the present moment—is critical; but equally essential and interdependent is the domain of sangha, or community. We need to discover who we are in relationship with others. Whether it is addiction or any other form of suffering, a mindful relationship with our inner life and with each other is what de-conditions the contracted beliefs, feelings and resultant behaviors.

What gives hope is described in recent science as neuroplasticity. The patterns in our mind that sustain suffering can be transformed. And how we pay attention is the key agent. A kind and lucid attention untangles the tangles!

Will This Serve?

DK: In your work, you really make a concerted effort to share your own fallibility, and I think that for psychotherapists that's a really tough one. I feel quite committed to that in my own practice, and yet I notice that I’m often pulled to frame things as, “long, long ago, when I was sick,” you know? But I’m not that old, so it couldn’t have been that long ago.

TB: Right…as long as there's a 10-year gap between now and when I was really confused…

DK: Exactly. So it’s something I really try to work on, because I know in my own experiences as a client in therapy and in supervision, that I feel safest and most connected when people are willing to share with me not just that they were screwed up in the past, but that they're still screwed up, because we all are.

TB: Yeah, the vulnerability, the fear, the shame—it all continues to rise throughout life. I’ve made that kind of vulnerable sharing a deliberate practice for a few reasons. One is, it's the truth. I mean, there's no way there's not going to be projection when you're a teacher or a therapist, but I really feel like mindfully sharing about our personal foibles serves. I regularly get caught up in self-centered thoughts, impatience, irritability, anxiety, the whole neurotic range. And…the truth is that I've been blessed to have increasing freedom, you know? That pain and difficulty and stuff keeps arising, but so does a mindful, compassionate way of relating to what’s happening. The result is there's less and less of a sense that it's happening to a self or caused by a self. I know how valuable it is for people to see that as a therapist or as a teacher that you have a certain amount of happiness or freedom in your life and that you're still working on things. It gives hope.

DK: Yes, it's a fine balance.

TB: It's a fine balance. I think the inquiry is always, will this serve? We're not doing it to unload; we're not doing it to be a certain kind of person. It's just, will this serve? But, I have found for myself that leaning in that direction is usually beneficial.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love

DK: You also talk a lot about love. I felt very clearly that I came into the profession in order to practice love—to practice it and to practice it, learn about it. But in my training, I literally never heard the word uttered. I made a point to bring it into discussions at school and at training sites, but in my experience it was a lot easier for people to talk about hate—“hate in the counter-transference” and love as just “positive countertransference.” Obviously there have been terrible abuses of power by therapists in the name of love, but it seems like the response has been an over-correction, and has left us without a proper vocabulary for what we are actually doing.

TB: Well, as you were speaking, I was thinking that it's beginning to change. That's the good news, Deborah. I mean, there is so much research now on self-compassion and compassion for others. There are universities like Stanford, which has a whole institute—The Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education (CCARE)—dedicated to compassion studies. Compassion is love when we experience another person's vulnerability or suffering. Love, in terms of loving-kindness, is described as love when we see the goodness in what we cherish. Gratitude and appreciation and love and beauty are all words and places, domains of attention that are actually becoming more common in the psychotherapeutic community.

And I feel like it's really important that we consciously take this one on. For instance, I have made a point of talking about prayer and talking about calling on the beloved and calling on loving presence when I feel very, very separate…really reaching out to that which feels like a source of loving presence and then discovering it wasn't outside of me, but I first have to go through the motions. So it starts with a dualistic sense, and then it ends up revealing unity. I've made a point of talking about that when I'm doing keynotes at professional conferences, because I really want there to be an increasing acceptance and comfort with the language of prayer.

How could it be that we all have these longings? I mean, every one of us longs to belong. Every one of us longs for refuge. We long for feeling embraced. We long to feel bathed in love. We long to touch peace.

Every one of us longs to belong. Every one of us longs for refuge. We long for feeling embraced. We long to feel bathed in love. We long to touch peace.That's prayer. That longing, when conscious and expressed, is the fullness of prayer, and for us to acknowledge the poignancy of it and invite people to recognize it and have it arise from a depth of sincerity, actually is a very powerful part of healing. Prayer is a powerful part of healing. It helps us step out of a small and separate ego kind of sensibility, and recognize a larger belonging.

So I feel like we're at a very juicy kind of era in psychotherapy where more and more of the profession is opening itself to intentional training and training in self-compassion. It has definitely opened its doors to that. It's opened the doors to mindfulness in a big way, and when you open those doors, people become more embodied and there's more creativity, more possibility.

The Squeeze

DK: The title of your new book is True Refuge, and it speaks to, I think, both the longing and the possibility for refuge inside of ourselves that we create in relation to others, as part of the human community. What’s the relationship between this new book and your first book, Radical Acceptance?

TB: Well, I wrote Radical Acceptance because I was aware in my own life and with most everybody I connected with that probably the deepest, most-pervasive suffering is that feeling that something is wrong with me.

Probably the deepest, most-pervasive suffering is that feeling that something is wrong with me.I called it the “trance of unworthiness,” because most people I know get it that they judge themselves too much and they're down on themselves, but are not aware of how many moments of their life that assumption of falling short is in some way constricting their behaviors and stopping them from being spontaneous. You know, it could be that here we are doing this interview, but there's some nagging sense of, "Oh, I should be doing this better," and how that in some way blocks the heart from being as open and tender. It's just, we're not aware of how many parts of our life are squeezed by a sense of deficiency.

I've found that until we are aware of that squeeze, we're caught in the trance. So I wrote the book because I wanted to say, “hey guys, we're all going around feeling bad about ourselves,” and explore how practices of freedom—cultivating a mindful awareness, cultivating compassion, cultivating a forgiving heart, learning to turn towards awareness itself to begin to recognize its formless presence that’s always here—help to dissolve the trance and reveal who we are. This vastness and this mystery is looking through our eyes right now, even though we're just looking at a computer screen—there's this sentience and it's so cool. So the purpose of Radical Acceptance was to very much draw attention to that trance.

DK: And what was the purpose of writing True Refuge?

TB: In True Refuge, I enlarged the scope because in addition to unworthiness, our basic trance of separateness gives us a very profound sense of uncertainty and loss. I think it becomes more vivid as we age that, “okay, these bodies go, everyone we love goes, these minds go.” Right now, for example, I’m watching my mother lose her memory as dementia is setting in. Just watching that happen is painful and sad.

But what directly motivated me to write True Refuge was a period of about 8 years of a steady decline in physical health. There was a time that I had no idea whether I'd regain any of my capacities I had lost. I have a genetic disease that affects my connective tissue, so I had to give up running, give up biking, and give up a lot of the recreational activities I most love. I remember at one point being completely filled with grief at the loss and sensing this deep longing, a very poignant longing, to love no matter what. Really I just wanted to find some refuge, some sense of peace and okay-ness, openheartedness, in the midst of whatever, including dying. That feels important to me. So True Refuge was approaching a broader domain: How do we find an inner sanctuary of peace in the midst of all the different ways that life comes and goes? How do we come home to that?

DK: When the pain of life brings you to your knees…

TB: Exactly. I remember being very struck by William James, who wrote that “all religions start with the cry, ‘help.’" Somehow deep in our psyches there is always some part of us that's going, "Okay, how am I going to deal with this life? How am I going to deal with what's around the corner?" What happens for most people—and this is kind of the way I organized True Refuge—is that we develop strategies to try to navigate life that often don't work. I call these false refuges. This is in all the wisdom traditions. We know that the grasping and the resisting and the overeating and the over-consuming and the distracting ourselves and the proving ourselves and the overachieving… just don’t create that sanctuary of safety and peace and well-being. It just doesn't work.

So in the book I talk about our false refuges and then explore what are really three archetypal gateways to homecoming. You can find them in all the different world religions including Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, and it's most clear for me through Buddhism. These three gateways are: truth (arising from mindfulness of the present moment), love and awareness. In Buddhism these are ordered differently and called Buddha (awareness), Dharma (truth) and sangha (love).

So the architecture of the book is based on that, and I used a lot of stories—my own stories, and other people's stories—to address the pain of feeling deficient, but a lot of other struggles also.

No Mud, No Lotus

DK: The parts of True Refuge that were most moving to me were the descriptions of your struggle with your disease, because there is just no getting around how painful and difficult that must be. You really share your cry for help and the fact that you've been able to make some peace with it is both awe-inspiring and hopeful, since all of us, as you say, will face our own physical demise. But it does seem like living with chronic pain that severely limits your mobility is one of the deeper sorts of spiritual challenges that we face. Do you feel grateful for what it's taught you?

TB: Yeah, I do. You know, I've heard many, many people say from the cancer diagnosis or the heart wrenching divorce or whatever it is that they wouldn't trade it for the world. I feel the same way. "No mud, no lotus," as the Buddhist saying goes. We wake up through the circumstances of our life, and the gift is that when it gets really hard you have to dig very, very deep into your being to find some sense of where love and peace and freedom are. Our experience of inner freedom is not reliable if it is hitched to life being a certain way. If I'm dependent on my body being able to run to feel good, I'm going to be in trouble. I’m actually better than I was before physically, but there were times when I couldn't leave my house. I couldn't do much of anything, and there was a growing capacity to come into a beingness and an openheartedness that allowed me to feel just as alive and present and happy as if I could have been romping around outside and running through the hills.

I think of that as freedom. I think of freedom as our capacity to be openhearted and awake and have some spaciousness in the midst of whatever is unfolding. The gift of it is that we start to trust who we really are. There's a sense of trust in the awareness that is here, the tenderness of our heart, the wakeful openness of our being. This becomes increasingly familiar, rather than the identify of a self-character that is able to do this and doesn't do that and is great or terrible at such and such. We are living from a sense of what we are that can’t be grasped by words or concepts, but can be realized and wholeheartedly lived.

So, that is the fruit of True Refuge—that our true refuge is our true nature. Our true refuge is our true nature. It's none other. The three gateways are just different energetic expressions of true nature.

DK: How did getting a degenerative chronic pain disease change your work with people?

TB: Before this happened, I was pretty much an athletic jock type that had some vanity around my fitness. And I've emerged much more humble, and also much more compassionate towards others. I know what loss is. There's something I sometimes call the “community of loss,” where each of us has lost something deeply important—whether we've lost a partner, or lost a job, or lost our health, our home. I just got back from teaching a weekend at Kripalu Retreat Center in Western Massachusetts, and a number of people there had been hit by hurricane Sandy. One woman was telling me what it was like to have her home totally demolished. The community of loss. The more awake we are to realizing we're part of it, the more we're holding hands with others, really the more compassionate a world we have.

Awakening to the World's Suffering

DK: Speaking of which, I know that political activism has been a big part of your work. You bring issues of social justice into your teachings. One of the things that comes to mind is a talk that you gave about racism within your spiritual community—not overt racism, but a more subtle but nonetheless insidious kind of racism that we find just about everywhere in our culture. It was painful for you to be made aware of it and you shared it as a way to bring awareness into your community. I have also appreciated the way that you struggle with modern politics in your work—trying to remain open-hearted but still having a coherent political voice. How important is it in the work that you're doing? How has that changed over time?

TB: Well, it only becomes increasingly clear to me that the awakening of our heart and mind means awakening to our belonging to the world and that there's not a spiritual path that can be extricated or isolated from that belonging. This means that not speaking is in fact making a statement. Our thoughts, our speech, and our actions in terms of the broader community completely matter. They matter. They express our awakeness and then they affect what happens in the world.

It feels essential that those who value being spiritually awake recognize that that includes being engaged consciously in our larger world, wherever it is that we feel particularly drawn.

It feels essential that those who value being spiritually awake recognize that that includes being engaged consciously in our larger world...We have to recognize that our earth is dying, that denial is the biggest danger in the world for our planet. We have to be willing to be touched by the suffering of the earth, the air, the creatures that are going extinct, to be touched by the pain that people experience when they've been discriminated against and shamed and isolated in different ways, marginalized in our culture—that’s part of being awake and open in the world.

DK: What kind of social or political activism are you currently involved in?

TB: I try to respond to what goes on in our own community, and our community is involved with a number of domains. There are some green activities that are, I think, pretty cool. We're fumbling around on the diversity front, sometimes in a painful way. Like most communities that have a majority of white people, the big question is how to wake up and be more responsive to the racism that is just naturally there. It's just part of the culture. I'm also very much supporting getting the mindfulness curriculum and mindfulness in schools around here. And we have a lot of activity around teaching in prisons. So the best I can do as a leader in the Washington area is to support those kinds of activities. As you can tell, I do feel passionately that it's not meant to be just on the cushion.

DK: So it's not separate at all—any of it.

TB: Nothing is separate. We belong to this world, and it's part of the way we're trying to bring compassion to these bodies and hearts and minds. We need to bring compassion to those that are suffering from an unjust society, and we need to bring compassion to the earth.

DK: Is there a place for anger in this struggle?

TB: Absolutely. We all are wired to have a range of emotions that are just life energies, and to not regard them as wrong or unspiritual is really important, to respect them. They all have an intelligent message, we wouldn't have been rigged with them if they didn't. Our work is to learn how to be in relationship with them in a way where we can listen, where we can embrace the life energy and not get identified with the storyline they may elicit.

What happens with anger is we can get fixated on, “You did something wrong to me.” When this happens, the practice is, instead of believing the story, to instead see if we can honor the energy and feel what's going on inside us.

Go ahead and speak your truth, but from a place of presence and intelligence and kindness, not from a burst of reactivity.This usually involves bringing real kindness and mindfulness to the feeling of being hurt, the feeling of vulnerability, the feeling of fear, but not buy into the storyline of, “you're bad and I need to get you back.” Because if we can pay attention to the message of anger—“there's some threat, I need to take care of it”—and feel where we feel threatened inside, we'll reconnect with the natural intelligence and compassion of our own heart-minds, and then respond with more wisdom. So go ahead and create boundaries, go ahead and speak your truth, but from a place of presence and intelligence and kindness, not from a burst of reactivity.

DK: Which takes a lot of practice over a lot of time.

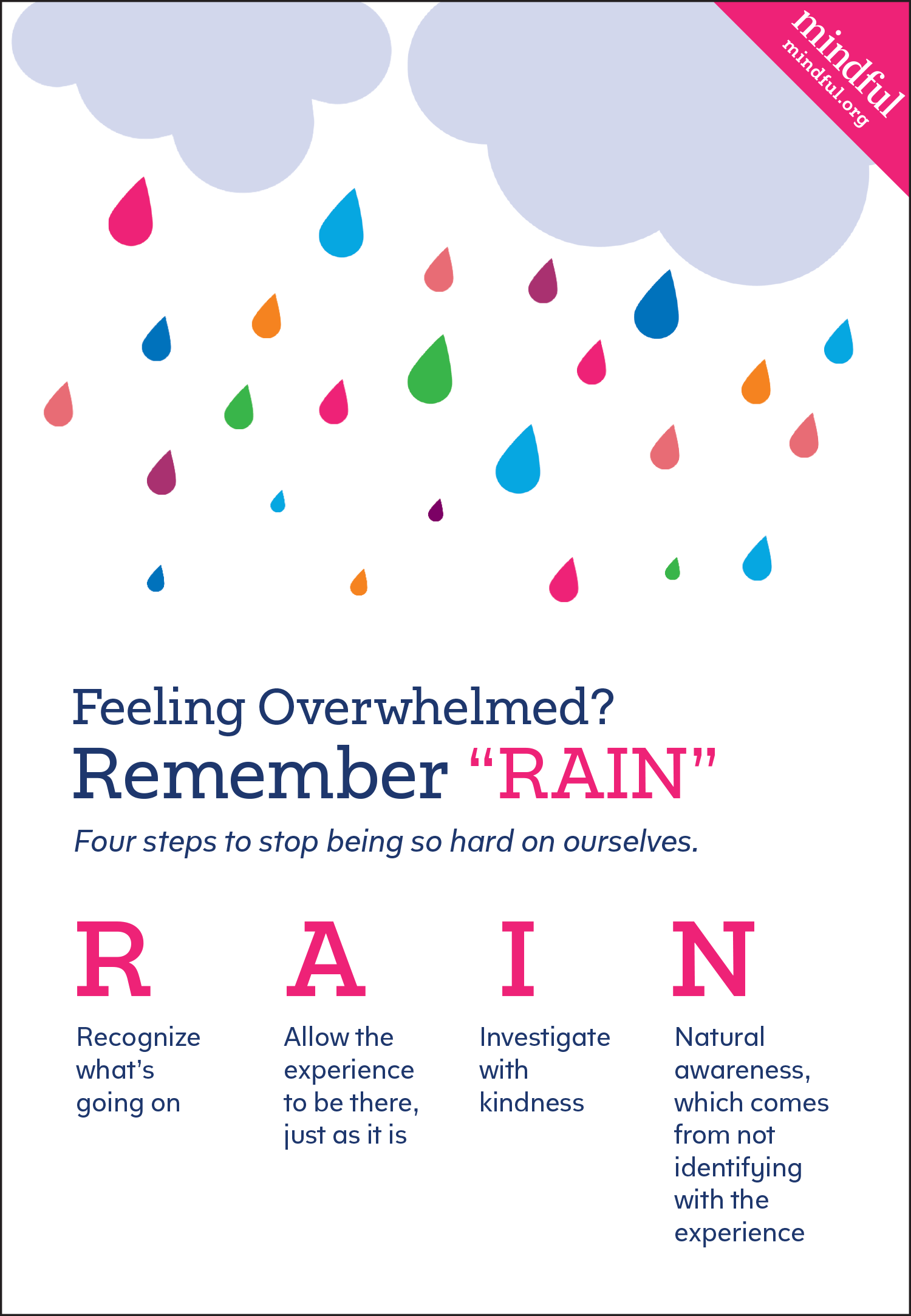

TB: Huge practice, because we're basically moving against our more primal reflexive reactivity, and learning to cultivate a response from the more recently evolved part of our brain. Our conditioning is to have an impulse arise and act out of it, so as to release the tension and feel soothed. It's coming back to that quote from Victor Frankl. This is saying, "Pause….First come home to the experience that is here and pay attention." That is the heart of the training, and it takes practice. In True Refuge, I use the acronym RAIN, and I've added some different dimensions than are usually emphasized in much of the Buddhist teachings. It's a really simple and powerful handle to, instead of react, come into a relationship with what's going on in a much more wise and balanced way.

RAIN

DK: Can you briefly go through what you mean by RAIN?

TB: Sure. RAIN is an acronym to support us in cultivating mindful awareness, and the basic elements of mindfulness are to recognize what's going on in the moment and to allow it. That’s the core of RAIN: to Recognize and Allow. What happens often is we've got a tangle going on—let’s say it's anger. We've got a storyline of the anger, and we've got the feelings, and we're wanting to do something, and it's all jumbled up. What we’re doing with RAIN is saying, "Okay, I Recognize anger is here and I Allow it."

But it's still feeling very sticky and very demanding of attention. So we deepen attention with the “I”—Investigate. But it has to be a compassionate investigation because if we investigate as a detached observer, or we investigate and there is some judgment and aversion, then the more vulnerable places within us will not reveal themselves to the investigation. For investigation to unfold to truth, we need to bring real compassion. I sometimes think of it as the rain of compassion or self-compassion, because we really need that quality.

DK: Yeah, it’s so easy to bring a subtle kind of judgment into that kind of investigation. Like, “why do I always trip out on this?” or “here’s my damn depression again.”

TB: If you think of a child who’s upset and you want to find out what's going on, if there's not a sense of caring, if you just ask questions, it's not going to work. So we begin to investigate within ourselves, ”Okay, anger. What am I believing right now?” If we ask that question, it can easily veer off into concepts. But the more we bring a gentle presence, a caring presence, a clear presence to the actual experience of what's going on, the more there is a shift in a sense of our identity. If you're very, very present with the anger, you're no longer the angry person believing in the story; you're the presence that's present. You are the awareness that's noticing. That shift in identity is the whole key to the transformation that Buddha talked about in awakening to freedom. And the body is the major domain of investigating—the throat, the chest, and the belly. Just really arrive and sense, "how is this experience playing out through this body?"

After the “I” of RAIN gives us that presence, the “N” is “Non-identification.” Another way to say it is the “N” is “Natural awareness.” We are re-embodying or reestablished in our natural, vast, compassionate awareness.

DK: So, it's really the opposite of dissociating?

TB: Exactly right. Neither dissociating nor getting possessed. When we’re identified with an experience, either it grabs us and we become the angry person, or we disassociate and become kind of numb and cerebral. Either one of those is, in a way, moving away from the reality of the present moment. RAIN is the way to come into the present moment. We can bring it into our relationships so that when there is conflict with another person, or with another country, or with some “other” that we consider kind of unreal or bad, if we're able to first bring RAIN inwardly and just sense what we're feeling and be with that presence and open up our sense of identity, we can then look at another person with the possibility of inquiry. What is really going on here? What is the unmet need? What is your vulnerability? What are the fears or hurts that might have led you to that behavior? We get to see through the eyes of wisdom. RAIN, or more broadly speaking this capacity for mindful awareness, is actually the grounds of compassion for ourselves and each other. It gives us a chance to really sense who we are beyond the mask.

DK: Thanks so much. It has been a joy to talk with you.

TB: Thank you.

© 2012 Psychotherapy.net, LLC

Order CE Test

$22.50 or1.50 CE Points

Earn 1.50 CreditsBUY NOW

*Not approved for CE by Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB)

View CE Test Learning Objectives

Bios

CE Test

Tara Brach, PhD., is a clinical psychologist, lecturer, and popular teacher of Buddhist mindfulness (vipassana) meditation. She is founder and senior teacher of the Insight Meditation Community of Washington, and teaches meditation at centers throughout the United States. Tara has offered speeches and workshops for mental health practitioners at numerous professional conferences. These, along with her many audio talks and videos address the value of meditation in relieving emotional suffering and serving spiritual awakening. Dr. Brach is the author of Radical Acceptance (Bantam, 2003) and True Refuge (Bantam, 2013.) www.tarabrach.com

Tara Brach, PhD., is a clinical psychologist, lecturer, and popular teacher of Buddhist mindfulness (vipassana) meditation. She is founder and senior teacher of the Insight Meditation Community of Washington, and teaches meditation at centers throughout the United States. Tara has offered speeches and workshops for mental health practitioners at numerous professional conferences. These, along with her many audio talks and videos address the value of meditation in relieving emotional suffering and serving spiritual awakening. Dr. Brach is the author of Radical Acceptance (Bantam, 2003) and True Refuge (Bantam, 2013.) www.tarabrach.com Deb Kory, PsyD, is the content manager at psychotherapy.net. She received her doctorate in clinical psychology from the Wright Institute and has a part-time private practice in Berkeley, CA. She loves both of her jobs and feels lucky to be able to divide her time between therapy, writing and editing. Before deciding to become a psychotherapist, she worked as the managing editor of Tikkun Magazine and published her writings in Tikkun, The Huffington Post and Alternet. Currently, she is working on turning her dissertation, Psychologists: Healers or Instruments of War?, into a book. In it, she describes in great detail the historical context and events that led to psychologists creating the torture program at Guantanamo and other "black sites" during the War on Terror.

Deb Kory, PsyD, is the content manager at psychotherapy.net. She received her doctorate in clinical psychology from the Wright Institute and has a part-time private practice in Berkeley, CA. She loves both of her jobs and feels lucky to be able to divide her time between therapy, writing and editing. Before deciding to become a psychotherapist, she worked as the managing editor of Tikkun Magazine and published her writings in Tikkun, The Huffington Post and Alternet. Currently, she is working on turning her dissertation, Psychologists: Healers or Instruments of War?, into a book. In it, she describes in great detail the historical context and events that led to psychologists creating the torture program at Guantanamo and other "black sites" during the War on Terror.