New Thought: A Practical American Spirituality Hardcover – 1 May 1995

by Alan Anderson (Author), Deborah Whitehouse (Author)

4.1 out of 5 stars 10 ratings

Kindle

$10.42Read with Our Free App

Hardcover

$46.11

This book introduces New Thought, a more than a century old movements dedicated to the healing of body,pocketbook,and interpersonal relationships through persistent positive thinking and the acceptance of one's indwelling divinity.

Print length

160 pages

C. Alan Anderson

In Memoriam: C. Alan Anderson (1930-2012)

Alan was born in Manchester, Connecticut on July 21, 1930. He died on November 25, 2012, of complications following surgery for a fractured hip suffered in a fall. He is survived by his wife and partner, Deborah G. Whitehouse; and a son from a previous marriage, Eric Alan Anderson.

He received his B.A. degree from American International College in 1952, an L.L.B. (later converted to J.D.) from the University of Connecticut School of Law in 1955, and an M.A. from the University of Connecticut Graduate School in 1957. Having been introduced to the more-than-a-century-old philosophico-religious New Thought movement through some books given to him by a former classmate, Alan decided to pursue a Ph.D. degree in philosophy “to determine whether New Thought was the greatest thing in the world or the nuttiest”. He earned his Ph.D. at Boston University in 1963, where he was influenced by his dissertation directors, personalist philosophers Peter Bertocci and John Lavely. His dissertation topic was Horatio W. Dresser and the Philosophy of New Thought, possibly the only major university Ph.D. degree in philosophy with a dissertation dealing with New Thought. His dissertation was later published by Garland with the title "Healing Hypotheses" and numerous appendices; it is now available online at www.ppquimby.com. Dresser, who earned his Ph.D. in philosophy at Harvard, was the eldest son of parents who were both patients of “the father of New Thought”, P. P. Quimby. They had met in Quimby’s offices and later married. New Thought can be summarized as “the practice of the Presence of God for practical purposes” or “habitual God-aligned mental self-discipline”. Two New Thought authors, Dresser and Henry Wood (1834-1909) were mentioned with approval by William James in Varieties of Religious Experience.

Other mentors introduced Alan to the process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead and his colleague, Charles Hartshorne. Since process thought is the only constructive postmodern philosophy, Alan saw almost immediately that it was a far more suitable metaphysical foundation for New Thought than the shifting sands on which it had rested. He then created what he came to call Process New Thought, which amalgamated the Bible-based Christian taproots of mid-nineteenth century Universalism embraced by Quimby with the upbeat, positive practices of New Thought (later supported by research in psychology) and the updated idealism of process thought, known as panexperientialism.

After teaching history and philosophy at Babson College for a few years, Alan spent 34 years as Professor of Philosophy and Religion at Curry College in Milton, Massachusetts, where he was instrumental in helping it earn its accreditation. His courses included Life After Death, Dimensions of Consciousness, Philosophy and Health Issues, American Philosophy, Social and Political Philosophy, Mysticism, World History, and (with his wife) Self Leadership Through Mind Management. Many of his courses were particularly popular with student nurses.

Books by Alan include The Problem is God (Stillpoint, 1985) and two books jointly authored with his wife: New Thought: A Practical American Spirituality (Crossroad, 1995, rev. ed. Author House, 2003) and Practicing the Presence of God for Practical Purposes (Author House, 2000). He also authored numerous pamphlets and monographs. Papers include “The Healing Idealism of P. P. Quimby, Warren F. Evans, and the New Thought Movement” (Bicentennial Symposium of Philosophy, 1976); “New Thought: A Link Between East and West” (Parliament of the World’s Religions, 1993), and “New Thought: Linking New Age and Process Thought (Center for Process Studies Silver Anniversary International Whitehead Conference, 1998). Many of Alan’s writings are available online at www.neweverymoment.com .

Alan was a member of the American Philosophical Association, the American Academy of Religion, the Center for Process Studies, the Metaphysical Society of America, the Society for the Study of Metaphysical Religion, The Academy for Spiritual and Consciousness Studies, and the International New Thought Alliance, in many instances as officer, Board member, or committee chairman.

Alan blended gentle wit, whimsy, charm, and humor with a passion for what he referred to as “ever-closer approximations of truth”. He was well known for defending unpopular positions in the interest of integrity. He took his work seriously but never himself; and although a stickler for proper grammar, he never met a pun he didn’t like. He coined the phrase "serial selfhood" to describe the process concept of a self as a whole series of experiences, reminiscent of the Buddhist concept of one candle lighting another; and he always explained to his audiences that this had nothing to do with flakes of corn or crisps of rice! His favorite bit of his own writing was a bit of doggerel that first appeared in a pamphlet, “God in a Nutshell”:

“I am tempted to say

That the best way to pray

Is to shut up your mouth

And get out of the way.

Simply listen for God

And go join God in play.”

---Deborah G. Whitehouse, Ed.D. (Mrs. Alan Anderson)

See more on the author's page

Follow

Deborah G. Whitehouse

Dr. Deb Whitehouse and her husband, Dr. C. Alan Anderson, are a team of educators, scholars who have studied the history of the century-old New Thought movement and practiced its teachings for many years. Both have served on the International New Thought Alliance Executive Board, and Deb is editor of its magazine. Alan and Deb collaborated on the first edition of "New Thought: A Practical American Spirituality" for Crossroad Publishing Company in 1995; followed by a Revised Edition in 2003. Their second jointly written book was "Practicing the Presence of God for Practical Purposes", published by Author House in 2000. Deb and Alan share a passion for Gilbert and Sullivan, for walks along the ocean, and for skewering sacred cows.

Top reviews

Top reviews from Australia

There are 0 reviews and 0 ratings from Australia

Top reviews from other countries

Cameron B. Clark

4.0 out of 5 stars A Valuable Introduction to New Thought MetaphysicsReviewed in the United States 🇺🇸 on 5 July 2001

Verified Purchase

American philosopher William James, in his book "Varieties of Religious Experience," called New Thought (NT) "the religion of healthy-mindedness" and considered it the American people's "only decidedly original contribution to the systematic philosophy of life." The authors consider Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802 - 1866) to be the modern founder of the movement although some of the philosophical roots go all the way back to the idealism of ancient Greece. Contemporaneous American influences include the transcendentalists, especially Ralph Waldo Emerson, who drank from the wells of eastern thought. The movement's "healthy-mindedness" began with Quimby's interest in mesmerism as it related to physical healing, but expanded through time to include mental, financial, and interpersonal well-being and success. Although the authors state that Quimby eventually rejected the idea, held by Franz Mesmer among others, of a subtle magnetic fluid that supposedly links all people and things together, it seems clear that he merely replaced it with the idea of "spiritual matter, or fine interpenetrating substance, directly responsive to thought..." (pg. 20). Truth (or Divine Wisdom) is considered the real cure for all ills. Through Warren Felt Evans and Emma Curtis Hopkins, the movement spread. Mary Baker Eddy, a disciple of Quimby and founder of Christian Science (CS), is considered a diversion from the stream. Eddy taught that "there is no life, substance, or intelligence in matter." But according to NT, matter is a part of God, not an illusion or error as taught by CS.

There are various New Thought denominations: Divine Science, Unity, Religious Science, and Seicho-No-Ie, among others. The umbrella organization is the International New Thought Alliance. The book notes that the founders of the various denominations, except the Japan-based Seicho-No-Ie, were from traditional Christian backgrounds which didn't meet their needs, especially for healing. It is noteworthy that the same general interest during the nineteenth century in divine and/or faith healing that produced NT also led to the current Pentecostal and Charismatic movements within traditional Christianity. Distinctions, however, are noted. The authors also note differences between the theology of NT and that of traditional Christianity (as they perceive it) as well as differences between traditional ("substance") New Thought and the more recent Process New Thought, which they promote. They admit that traditional NT is more or less pantheistic and believe that the limitations of such a world view are overcome by the panentheism of Process New Thought.

Other discussions include the similarities and differences between NT and the New Age Movement (NAM), including the occult and magic. They observe that both the NAM and NT have a growing interest in panentheism (as expounded by Whitehead and Hartshorne) but feel that the NAM is overly interested in occult trappings such as crystals, pyramids, magic, and the like. They consider NT to be more mystically rather than magically (or psychically) inclined. Also discussed is NT's position on ethics and evil. The authors state: "...unlike Hinduism or Christian Science, it [NT] does not see evil as maya, illusion"... "Evil is good that is immature or misdirected. It has no power of its own; it has only the power that our minds give to it..." (pg. 50). This follows from NT's idea that "there is only one Presence and Power, and that power is good." Regarding sin, they say: "It is New Thought that understands that we are punished by our sins, not for them, and that by rising in consciousness we can contact the Divine Intelligence within, learn what we need to learn, and straighten out our thinking - and our lives" (pg. 51). Regarding ethics, the authors note the distinction between the shallow personality ethic and the more substantial character ethic and see the need to reemphasize the latter in New Thought.

Although I don't agree with the overall theology of New Thought, I consider this book essential to understanding the movement. It has also provided valuable historical and philosophical links in my own research in areas only superficially covered or overlooked by the authors. For example, the authors note that some self-professing Christians such as Norman Vincent Peale and Robert Schuller have incorporated NT principles into their teachings on positive thinking without adopting pantheism or panentheism. Both Peale and Schuller have been criticized by other Christians for their views. But neither is Pentecostal or Charismatic (P/C). Within the P/C movements is another movement that the authors do not mention in their book and may not be aware of: The Word of Faith Movement. This movement has some things in common (not necessarily all bad) with New Thought and is also criticized by other Christians, including some fellow P/C Christians. For those who are interested, see the Dictionary of Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements in the book's bibliography. In the areas of evil, ethics, and occultism, the authors provided superficial coverage. Without giving too much detail, traditional Christianity's concepts of sin and evil are more complex. Evil is seen more as "spoiled goodness" (C. S. Lewis) than immature or misdirected goodness, and includes the idea that at least some sin is intentional, not in ignorance, and deserving of punishment. Punishment is integral to vicarious atonement. The idea, however, that we are punished by our sins has a place too. Also, an eschatological dimension is lacking in the book although NT implies a type of universalism (everybody will be saved) that denies hell and has much in common with the Unitarian Universalists (not mentioned in the book). Reincarnation is usually promoted, but this also isn't mentioned.

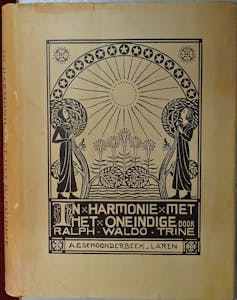

The authors' attempt to distinguish NT from occultism and magic fails to see the deeper connection. Like the authors, serious occultists shy away from the largely shallow New-Agers who are more into dabbling than discipline. Also, Evelyn Underhill, in her massive book "Mysticism," in the chapter entitled "Mysticism and Magic," provides information on occult magic which parallels and links to New Thought metaphysics. One of the key axioms of occult magic (or magick) is "the existence of an imponderable medium or universal agent which is described as beyond the plane of our normal sensual perceptions yet interpenetrating and binding up the material world." Sound familiar? Remember the interpenetrating "magnetic fluid" and "spiritual matter"? Well, occultists call it "the astral light," among other names (akasha, ether, quintessence, etc.). The second axiom of magic is "the limitless power of the disciplined human will." Ms. Underhill says: "this dogma has been `taken over' without acknowledgment from occult philosophy to become the trump card of menticulture, `Christian Science,' and `New Thought.'" Richard Cavendish, in his book "A History of Magic," says: "Mesmer was a powerful influence on the development of Spiritualism, Christian Science and the New Thought movement. His significance for magic was that he appeared to have demonstrated the existence of a universal medium or force responsive to the human mind, which could employ it to affect the behavior of others. For magicians this was a welcome gift and Eliphas Levi, the leading French magus of the nineteenth century, turned Mesmer's magnetic fluid into one of the bastions of modern magical theory." There is certainly an overlap between mysticism and magic, but distinctions as well. I've noticed the terms are used loosely by magicians. Some divide magic into two general groups: high magic (theurgy) and low magic (thaumaturgy). The former is sometimes associated with mysticism and spiritual progress whereas the latter is more concerned with strict wonder-working apart from any reference to salvation or sanctification. The book doesn't get into any of this in any depth. One of the best traditional Christian critiques of pantheism and panentheism and defenses of Christianity is Norman Geisler's Christian Apologetics. One of the "best" expositions of New Thought metaphysics is "In Tune With the Infinite" by Ralph Waldo Trine. A recent book by a Neo-Pagan, Gus DiZerega, entitled "Pagans & Christians" explains how pantheism and panentheism relate to Neo-Pagans and Wiccans.

Read less

71 people found this helpfulReport abuse

Ken Wolf

4.0 out of 5 stars Perhaps the most thoughtful and unbiased account (even humorous in ...Reviewed in the United States 🇺🇸 on 3 March 2017

Verified Purchase

Perhaps the most thoughtful and unbiased account (even humorous in places) written by an "insider." The only part that was difficult to understand was the discussion of process theology--but even that was a bit clearer than other accounts I have read of the difficult subject.

It should be read with Mitch Horowitz's "One Simple Idea" written several years ago. Both of these books are written by people who appreciate New Thought but who are also aware of its weaknesses (especially true of Horowitz) and of how it can be misinterpreted and misunderstood by Positivist intellectuals who think "positive thinking" is a con.

3 people found this helpfulReport abuse

Dr. C. H. Roberts

5.0 out of 5 stars Excellent introduction and historyReviewed in the United States 🇺🇸 on 23 September 2005

Verified Purchase

The authors have given us a marvelous, easy to read, introduction and history of New Thought. The material is at once simple and to the point for the "average" reader, but those with previous knowledge of New Thought metaphysics will not find it simplistic. Anderson and Whitehouse are clearly "at home" discussing both the past history and current issues of modern debate (especially Process Theology's influence in some areas of New Thought). I highly recommend this book to all interested readers and sincerely thank the authors of a job well done.

8 people found this helpfulReport abuse

Jason Fairbanks

5.0 out of 5 stars When the Student is Ready the Book Will ComeReviewed in the United States 🇺🇸 on 3 June 2013

Verified Purchase

I was drawn to this book after happening upon the authors' website. As a student and former bookseller, I have to admit that I was a bit hesitant in reading a book not published by a major publisher. However, this was exactly the book I needed.

It is very clear and well written. I did not find it "dry" in the least. It is an outstanding primer on the history and lineage of the New Thought movement. It is very helpful for someone like me who is coming from a (loosely) orthodox Christian perceptive.

The authors give just enough of a taste of their ideas about practice to whet my apetite for their other book.

2 people found this helpfulReport abuse

Tim Stewart

5.0 out of 5 stars Highly RecommendedReviewed in the United States 🇺🇸 on 26 October 2005

Verified Purchase

This is a great book for anyone interested in knowing more about New Thought. The authors detail the beliefs of most major New Thought organizations and explain the differences between New Thought and new age. I highly recommend this book to those who may be new to New Thought, ESPECIALLY those coming from a fundamental background.

7 people found this helpfulReport abuse

See all reviews

Mary Baker Eddy.

Mary Baker Eddy.

Dr. Norman Vincent Peale is shown in 1968 as pastor of Marble Collegiate Church in New York City. AP Photo

Dr. Norman Vincent Peale is shown in 1968 as pastor of Marble Collegiate Church in New York City. AP Photo What is Trump’s Christianity?

What is Trump’s Christianity?