현응 (지은이)불광출판사2016-08-12

정가

17,000원

판매가

15,300원 (10%, 1,700원 할인)

Sales Point : 551

이 책 어때요?

기본정보

반양장본

360쪽

152*225mm

551g

ISBN : 9788974793227

책소개

<깨달음과 역사> 개정증보판. 개정증보판에서는 '깨달음 논쟁'을 촉발시킨 <깨달음과 역사, 그 이후>를 비롯해, <'깨달음과 역사, 그 이후' 반론에 대한 답변>, <기본불교와 대승불교> 원고를 새롭게 추가했다. 또한 표지 디자인에 획기적인 변화를 주어, 불교의 원형질을 이루는 유전자인 무상, 무아, 연기, 공, 자비를 변화와 관계성의 이미지로 추상화하여 현대적으로 형상화했다.

이 책의 중심 내용은 불교를 구체적인 우리의 삶과 역사에 접목시키기 위한 노력이지만, 또 다른 중요한 가치는 불교는 어렵고 난해하다는 인식을 바꿔주는 데 있다. 특히 1장 '사제에게 보내는 열두 번의 편지'에서는 어렵게만 느껴지던 불교 용어와 교리를 쉽고 진솔하게 풀어주고 있어 불교입문서 역할을 톡톡히 해준다. 깨달음, 연기, 공, 윤회, 대승과 소승 등 애매하고 모호하게 다가왔던 개념들이 명확한 실체로 다가온다.

목차

서문 『깨달음과 역사』를 다시 펴내며

1장 사제(師弟)에게 보내는 열두 번의 편지

1월_ 대승과 소승

2월_ 무심시도(無心是道)

3월_ 확연무성(廓然無聖)

4월_ 윤회와 해탈

5월_ 색즉시공 공즉시색

6월_ 공(空)의 이중적 구조

7월_ 대도무문(大道無門)

8월_ 깨달음과 역사

9월_ 돈오점수설, 돈오돈수설에 대해

10월_ 마음·부처·중생

11월_ 보살만행(菩薩卍行)

12월_ 불국정토(佛國淨土)

2장 각(覺) - 깨달음

3장 깨달음을 위한 산책

4장 돈오점수, 돈오돈수설 비판

5장 역사에 다가가는 불교

불교와 사회

불교의 사회적 실천

민중불교운동의 대승적 전개를 위하여

6장 기본불교와 대승불교

7장 깨달음과 역사, 그 이후

깨달음과 역사, 그 이후

‘깨달음과 역사, 그 이후’ 반론에 대한 답변

접기

책속에서

이 책에 수록된 내용들은 일관된 문제의식과 주제를 포함하고 있다. 그것은 바로 ‘깨달음(Bodhi, 연기적 관점)’과 ‘역사(Sattva, 인생과 세상)’에 대한 것이다. 따라서 이 책에서 말하는 깨달음은 ‘역사를 연기적으로 파악하는 시각’을 말하며, 역사란 ‘깨달음의 시각으로 비춰보고 실현하는 현실적 삶’을 뜻한다.

이러... 더보기

P. 20 나는 불교만큼 오해를 받는 가르침도 드물다고 생각합니다. 부처님의 중요한 가르침은 거의 모두 곡해되고 굴절되어 이해되고 있습니다. 그 가운데 대표적인 것 하나가 바로 불교는 무심한 종교라는 것입니다. 모든 시비분별을 떠난 초연한 은자로서의 태도는 불교인의 독특한 성격처럼 되어버렸습니다. 조는 듯 잠자는 듯한 침묵과 웃을 듯 말 듯 달관한 듯한 무관심이 적멸과 열반의 경지로 받아들여지고 있습니다. 접기

P. 34 사제님도 동의할 줄 압니다만, 나는 윤회라는 것을 비단 어떤 사람이 칠십 년쯤 살고는 죽고 그리고 다시 태어나고 하는 식의, 심지어는 개로도 태어나고 새로도 태어나는, 그런 계속되는 생명의 쳇바퀴 현상으로만 보지 않습니다. 염불 구절에도 나오는 바, “일일일야 만사만생(一日一夜 萬死萬生)”이니 하루에도 수만 번 나고 죽는 일을 계속 하는 것이 바로 윤회의 실상이 아니겠습니까? 곧 윤회란 변화를 뜻하는 말이며 그 내용은 끊임없는 생성과 소멸의 과정을 말합니다. 접기

P. 191 깨달은 사람이 깨달음의 영역에 자족하지 않고 왜 역사의 길에 나서게 되는가? 존재에 대한 사랑[慈]과 연민[悲] 때문이다. 자비야말로 역사적 행위의 원동력으로서 깨달음과 역사를 묶어 내는 고리이다. 이 자비가 구체적으로 표출된 모습이 방편(方便), 원(願), 역(力)이라 부르는 불교적 행동양식이다. 원(願)이란 역사에 대한 어떤 목표 설정에 해당되며, 역(力)이란 원(願)을 최종적으로 성취하게 하는 불굴의 신념을 뜻하며, 방편이란 원(願)을 성취하는 구체적 방법론과 실천을 말한다. 따라서 원력과 방편은 자비의 역사적 표출에 다름 아니다. 깨달음만 있는 사람은 아라한(Arhan)이라 부른다. 깨달음에다 자비와 원력을 덧붙인 사람은 보살(Bhodhisattva)이라 부른다. 아라한이란 ‘깨달음’이라는 단일 언어로 이루어져 있고, 보살이란 ‘깨달음(보디)’과 ‘역사(사트바)’의 복합 언어로 이루어져 있다. 아라한은 소승의 삶이라 불리고 보살은 대승의 삶이라 불린다. 접기

P. 315 부처님은 깨달음을 고도로 수련된 높은 정신세계를 이루는 것이라 하지 않았다. 깨달음은 ‘잘 이해하는 것’이라고 하셨다. 깨달음이란 ‘잘 이해하는 것(understanding)’이라 말하면 수준이 떨어지는가? 깨달음을 ‘~에 대한 이해’로 볼 것인가, 그렇지 않으면 ‘몸과 마음의 완성된 그 어떤 경지’로 볼 것인가에 따라 깨달음을 이루고자 하는 방법도 크게 달라질 것이다. 깨달음을 얻는 데 소요되는 시간이나 기간은 말할 것 없이 크게 차이날 것이다. 만일 깨달음을 ‘올바른 이해’라고 한다면 그러한 깨달음을 얻는 데는 그리 오래 걸리지 않을 것이다. 부처님 자신도 고행을 통해서도 아니요 선정을 통해서도 아닌, 논리적인 사유와 성찰을 통해서 깨달음을 얻었다. 부처님이 녹야원의 첫 설법에서 다섯 수행자에게 당신의 깨달음의 세계를 설명하고 납득시키는 데 걸린 시간은 불과 며칠이 걸렸을 뿐이다. 그리고 ‘납득시킨다’는 말을 썼듯이 깨달음은 이해의 영역이라는 것이다. 납득시키는 방법도 선정삼매를 통한 것이 아니라 밤낮 없는 대화와 토론이었다. 접기

저자 및 역자소개

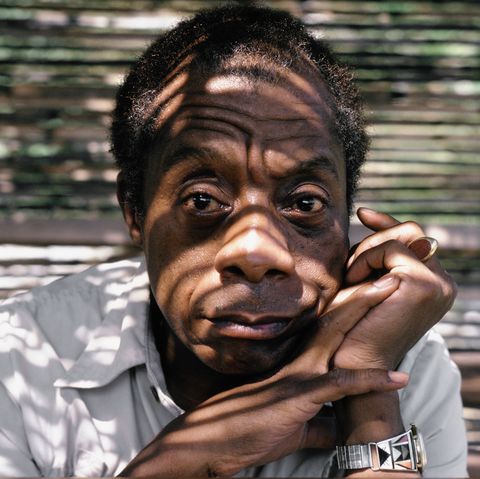

현응 (지은이)

저자파일

최고의 작품 투표

신간알림 신청

1955년 경남 창원에서 태어났다. 불교에 인연이 있어 1971년 해인사로 출가해 종성(宗性) 화상을 은사로 수계했다. 해인사승가대학을 졸업하고 봉암사, 해인사 등 제방 선원에서 정진하기도 했다. 해인사승가대학에서 강의를 하였으며, 대승불교승가회, 선우도량 등 불교 단체를 결성하여 활동했다. 대한불교조계종 총무원 기획실장, 중앙종회의원, 불교신문사 사장, 해인사 주지 등을 역임했고, 현재 대한불교조계종 교육원장으로 재임중이다.

최근작 : <Enlightenment and History : Theory and Praxis in Contemporary Buddhism>,<깨달음과 역사>,<깨달음과 역사> … 총 6종 (모두보기)

출판사 제공 책소개

이미 고전의 반열에 오른, 최초의 불교역사철학 에세이!

조계종 교육원장 현응 스님의 『깨달음과 역사』 초판은 26년 전인 1990년 해인사출판부에서 출판됐다. 민주화의 열기가 봇물처럼 넘쳐나던 1980년대 중후반에 쓴 원고를 모아 엮은 것으로, “불교의 인식론과 존재론을 깨달음(보디)의 영역으로, 현실과 실천의 범주를 역사(사트바)의 영역으로 거두어들인 최초의 불교역사철학 에세이. 완전히 새롭게 불교해석을 함으로써 불교도에게 세상을 보고 역사를 인식하는 안목을 열어주고, 보살행 실천의 지침을 제공해 주는 역작.”이라는 찬사와 함께 한국불교계에 큰 반향을 일으켰다.

세월이 흘러 출판사 사정으로 절판된 뒤로는 복사본을 만들어 돌려보는 등 독자들의 한결같은 성원에 힘입어, 2009년 20년 만에 불광출판사에서 새롭게 개정판으로 나왔다. 개정판은 4쇄를 찍으며 여전히 독자들로부터 큰 호응을 이끌어냈다. 이후 2015년 9월 열린 『깨달음과 역사』 발간 25주년 기념 학술세미나 ‘깨달음과 역사, 그 이후’를 계기로, 불교계에 신선한 충격과 함께 스님들과 불교학자들 중심으로 깨달음에 대한 뜨거운 논쟁을 불러일으켰다. 이러한 ‘깨달음 논쟁’은 “오랜만에 추문이나 논란이 아닌 본질에 대한 논쟁이 벌어지고 있다.”는 긍정적인 반응 속에서 1년 가까이 지난 현재까지 활발히 진행중이다.

이번에 출간된 『깨달음과 역사』 개정증보판은 ‘깨달음 논쟁’을 촉발시킨 <깨달음과 역사, 그 이후>를 비롯해, <‘깨달음과 역사, 그 이후’ 반론에 대한 답변>, <기본불교와 대승불교> 원고를 새롭게 추가했다. 또한 표지 디자인에 획기적인 변화를 주어, 불교의 원형질을 이루는 유전자인 무상, 무아, 연기, 공, 자비를 변화와 관계성의 이미지로 추상화하여 현대적으로 형상화했다.

아직까지 『깨달음과 역사』를 접하지 못했다면, 일독을 권해본다. 지금까지 자신이 알고 있던 불교에 대한 고정관념이 하나하나 벗겨지는 놀라운 체험과 더불어 고전이 주는 묵직한 감동을 온전히 느낄 수 있을 것이다.

현응 스님이 깊은 인문학적 소양으로 갈파한

대승불교의 이상적인 인간상, 보살(Bodhisattva)

『깨달음과 역사』는 현응 스님의 독서와 사색, 수행, 실천행의 결정체이다. 현재 조계종 교육원장으로서 시대에 부응하는 승가교육개혁을 진두지휘하고 있는 스님은 일찍이 1994년 조계종 개혁회의 기획조정실장으로 현 종헌 종법의 기틀을 마련하였다. 또 종단의 굵직굵직한 중책을 맡아 탁월한 능력을 발휘, ‘조계종의 재사(才士)’라는 별명을 얻었다. 책을 손에서 놓지 않는 스님은 동서양 고전을 섭렵한 것은 물론, 최신 인문학 서적들을 챙겨 읽으면서 세상과 소통한다. “명석한 두뇌에 경학을 깊이 공부하고, 자기 사상과 입지가 분명한 사람”, “마음 씀이 부드러우나 일을 함에 굳은 신념을 가지고 추진하는 외유내강한 사람”으로 정평이 나있다.

한국불교는 대승불교를 지향한다. 대승불교의 이상형은 보디사트바(보살)이다. 스님은 이 책에서 보디와 사트바를 새로운 관점에서 해석하고 의미 부여를 하였다. 『깨달음과 역사』라는 제목처럼 이 책에 일관되게 흐르고 있는 주제는 ‘깨달음(Bodhi, 연기적 관점)’과 ‘역사(Sattva, 인생과 세상)’이다. 현응 스님은 깨달음은 ‘모든 번뇌를 끊고 고매한 인격을 이룬 높은 경지’가 아니라 ‘세상을 연기(緣起)의 관점으로 바르게 이해하는 것’이라고 강조한다. 깨달음이란 변화와 관계성의 법칙을 깨닫는 것, 다시 말해 삼라만상이 서로 연기적으로 존재하는 것임을 깨닫는 일임을 역설한다.

“보디사트바(보살)란 ‘깨달음(보디)’과 ‘역사(사트바)’의 합성어가 되는 것입니다. 통속적인 표현으로 ‘깨달음의 역사화’, ‘역사의 깨달음화’라고 하고 싶습니다만, 이 보살의 삶에 있어서는 그의 깨달음에 기초하는 역사로부터의 자유로움만 만끽하는 것은 아닙니다. 한 걸음 더 나아가 역사와 교섭하도록 적극 참여하여 그 자신을 투사시킨다고나 할까요. 표현은 뭐 합니다만, 저는 이것을 ‘역사로부터의 자유(freedom from being and history)’와 ‘역사에로의 자유(freedom to being and history)’를 겸한 삶이라고 말하곤 합니다.”

현응 스님은 깨달은 사람이 깨달음의 영역에 자족하지 않고 역사의 길에 나서는 것은 존재에 대한 사랑[慈]과 연민[悲] 때문이며, 자비야말로 역사적 행위의 원동력으로서 깨달음과 역사를 묶어내는 고리임을 거듭 강조한다. 깨달음과 역사가 따로 존재하지 않고 결합되었을 때, 비로소 우리 삶에 희망이 솟아나는 것이다.

그동안 우리가 알고 추구하던 불교는 너무도 ‘가난한 불교’였다. 맹목적으로 깨달음만 추구하며, 삶과 역사에 대한 이해와 관심이 부족했다. 깨달음은 신비롭거나 높디높은 경지가 아니다. 우리의 존재를 비롯한 모든 삼라만상을 변화와 관계성의 연기적 관점으로 올바르게 이해하는 데 있다. 이러한 깨달음이 역사의 현장에서 깊이 실천될 때 불교는 나와 세상을 두루 구제할 수 있다.

불교를 제대로 공부하고 실천할 수 있는

가장 정교한 입문서이자 바른 길잡이

이 책의 중심 내용은 불교를 구체적인 우리의 삶과 역사에 접목시키기 위한 노력이지만, 또 다른 중요한 가치는 불교는 어렵고 난해하다는 인식을 바꿔주는 데 있다. 특히 1장 ‘사제(師弟)에게 보내는 열두 번의 편지’에서는 어렵게만 느껴지던 불교 용어와 교리를 쉽고 진솔하게 풀어주고 있어 불교입문서 역할을 톡톡히 해준다. 깨달음[覺], 연기(緣起), 공(空), 윤회, 대승과 소승 등 애매하고 모호하게 다가왔던 개념들이 명확한 실체로 다가온다.

그리고 더욱 중요한 것은 불교를 머리로만 이해하는 것이 아닌, 불교정신이 우리의 삶 속에서 어떠한 행위로서 구현되어야 하는지를 밝히며 직접적인 실천으로 이끈다. 깨달음에 대한 개념과 수행법, 깨달은 사람의 삶의 모습, 보살이 역사의 현장에서 구체적으로 어떻게 살아가야 할지를 분명하게 제시하며 안내한다.

『깨달음과 역사』가 출간된 지 26년이 지난 지금, 과거보다 더욱 활발한 논의를 만들고 있는 것은 주목해 볼 만한 현상이다. 현응 스님이 이 책에서 설파하고 주장하는 내용이 누군가에게는 낯설고 불편할 수도 있다. 한국불교가 그동안 전통적 교리와 신행 방법만 고수하며 시대의 변화를 외면하지는 않았는지, 개인의 삶과 사회에 어떠한 역할을 했는지 반성이 필요한 지점이다. 불교정신과 사상이 역사현실 속에서 적극적으로 작동해야 한다는 현응 스님의 문제의식이 그동안 암묵적 침묵에 가려져 왔다면, 지금의 ‘깨달음 논쟁’은 여간 반가운 일이 아닐 수 없다. 그런 의미에서 이 책은 새로 출발하는 불교를 제안하고 있으며, 기존 불교의 재정립을 촉구하고 있다. 접기

그동안의 강의내용을 정리해서 모아놓은책. 이 시대에 불교인이 나아가야할 점에 대해 생각해보게 만드는 책이다. 대승과 소승, 돈오와 점수, 깨달음이란 무엇인가 하는 기본적이지만 사실은 자세히 얘기하길 꺼려왔던 문제에 대해서도 정리해놔서 소장가치가 있다고 봄.

타는목마름으로 2016-09-16 공감 (1) 댓글 (0)

Thanks to

[마이리뷰] 깨달음과 역사

그동안 불자로 지내면서 어색했던 부분들을 일소해 쓸어버리는 듯 강렬한 인상을 준 책이다.

2500년 전의 가르침이 지금도 이어진다는 거야 고전을 읽는 사람들에게 익숙한 이야기겠지만, 나는 그 가르침 자체보다 그것이 전수되는 방식이 늘 같기는 커녕 더 어려워지는 듯 하여 어색했었다. 때로는 그간의 문화, 문명, 지식수준의 변화를 간과할 수 있는가 의문을 갖기도 했다.

쉽게 말해서 지금 사람들이 2500년 전 사람들보다 훨씬지식도 뛰어나고 이해력도 좋고, 배경 환경도 비교안될 정도로 좋은데, 그 부처님의 가르침을 이해하는 건 왜 더 오래걸리느냐의 문제였다.

현응스님은 이런 문제에 대해 답할 뿐만아니라 대승불교의 진정한 의미까지..

내가 생각하고 대충 그러려니.. 하는 문제들까지 싹 정리해서 문제제기를 하고 있다.

이 책이 왜 논란이 됐는지 알만했다.

밑줄치기를 중단했다. 모든 페이지에 밑줄을 쳐야할 것만 같아서다. 두고두고 읽어봐야겠다.

아, 현응스님의 답이 궁금한가?

부처님의 가르침, 즉 깨달음은 연기에 대한 이해를 통해 습득할 수 있는 것이라고 한다. 왕조시대고 책도 많이 없던 부처님 당시로서는 놀라운 이야기지만 지금은 그다니 혁명적인 이야긴 아닐 것이다.

그렇다면 우리가 할 일은? 우리의 수행은 끝인가?

그리고 그간 열심히 공부하며 수행하는 사람들은 헛수고인가?

그렇게 이분법적으로 볼 일이 아니다.

이 책이 놀라운 점은 이런 걸 융합한다는 데에 있다.

두고두고 봐야하는 이유다.

- 접기

모닥불 2018-01-01 공감(2) 댓글(0)