Upasika Kee Nanayon and the Social Dynamic of Theravadin Buddhist Practice by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

From the Introduction to the

book

"An Unentangled Knowing: The Teachings

of a Thai Buddhist Lay Woman"

Published in 1995

* * * * * * * *

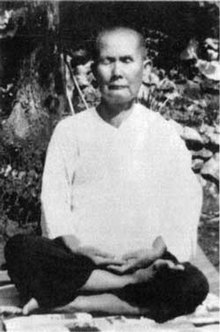

Upasika Kee Nanayon, also known by her

penname, K. Khao-suan-luang, was

arguably the foremost woman Dhamma teacher in twentieth-century Thailand.

Born in 1901 to a Chinese merchant family in Rajburi, a town to the west of Bangkok, she was the

eldest of five children -- or, counting

her father's children by a second wife, the eldest of eight.

Her mother was a very religious woman and taught her the rudiments of Buddhist practice, such as

nightly chants and the observance of

the precepts, from an early age. In

later life she described how, at the

age of six, she became so filled with fear and

loathing at the miseries her mother went through in being pregnant

and giving birth to a younger sibling

that, on seeing the newborn child for

the first time -- "sleeping quietly, a little red thing with black, black hair" -- she ran away from

home for three days. This experience, plus the anguish she must have

felt when her parents separated,

probably lay behind her decision, made when she was still quite young, never to submit to what she saw

as the slavery of marriage.

During her teens she devoted her spare time

to Dhamma books and to meditation, and

her working hours to a small business to support her father in his old age. Her meditation progressed well enough that

she was able to teach him meditation,

with fairly good results, in the last

year of his life. After his death she

continued her business

with the thought of saving up enough money to

enable herself to live the remainder of

her life in a secluded place and give herself fully to the practice. Her aunt and uncle, who were also interested

in Dhamma practice, had a small home

near a forested hill, Khao Suan Luang

(RoyalPark Mountain), outside of Rajburi, where she often went to practice.

In 1945, as life disrupted by World War II had begun to return to normal, she gave up her business,

joined her aunt and uncle in moving to

the hill, and there the three of them began a life devoted entirely to meditation. The small retreat they made for themselves in an abandoned monastic dwelling

eventually grew to become the nucleus

of a women's practice center that has flourished to this day.

Life

at the retreat was frugal, in line with the fact that outside support was minimal in the early years. However, even now that the center has become well-known and

well-established, the same frugal style

has been maintained for its benefits in subduing greed, pride, and other mental defilements, as well as for

the pleasure it offers in unburdening

the heart. The women practicing at the

center are all vegetarian and abstain

from such stimulants as tobacco, coffee, tea,

and betel nut. They meet daily

for chanting, group meditation, and

discussion of the practice. In

the years when Upasika Kee's health was

still strong, she would hold special meetings at which the members would report on their practice, after which

she would give a talk touching on any

important issues that had been brought up.

It was during such sessions that

most of the talks recorded in this volume

were given.

In the center's early years, small groups

of friends and relatives would visit on

occasion to give support and to listen to Upasika Kee's Dhamma talks. As word spread of the high standard of her

teachings and practice, larger and

larger groups came to visit, and more women

began to join the community. When

tape recording was introduced to

Thailand in the mid-1950's, friends began recording her talks and,

in 1956, a group of them printed a

small volume of her transcribed talks

for Distribution. By the

mid-1960's, the stream of free Dhamma

literature from Khao Suan Luang -- Upasika Kee's poetry as well as

her talks -- had grown to a flood. This attracted even more people to her center and established her as one of the

best-known Dhamma teachers, male or

female, in Thailand.

Upasika Kee was something of an autodidact. Although she picked up the rudiments of meditation during her

frequent visits to monasteries in her

youth, she practiced mostly on her own without any formal study under a meditation teacher. Most of her instruction came from books -- the Pali Canon and the works of

contemporary teachers -- and was tested

in the crucible of her own relentless honesty.

Her later teachings show the

influence of the writings of Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, although she transformed his concepts in

ways that made them entirely her

own.

In the later years of her life she

developed cataracts that eventually

left her blind, but she still continued a rigorous schedule of meditating and receiving visitors

interested in the Dhamma. She passed away quietly in 1978 after entrusting

the center to a committee she appointed

from among its members. Her younger

sister, Upasika Wan, who up to that

point had played a major role as supporter and

facilitator for the center, joined the community within a few

months of Upasika Kee's death and soon

became its leader, a position she held

until her death in 1993. Now the

center is once again being run by

committee and has grown to accommodate 60 members.

Much has been written recently on the role of

women in Buddhism, but it is

interesting to note that, for all of Upasika Kee's accomplishments in her own personal Dhamma

practice and in providing opportunities

for other women to practice as well, socio-historical books on Thai women in Buddhism make no

mention of her name or of the community

she founded. This underscores the

distinction between Buddhism as

practice and mainstream Buddhism as a socio-historical phenomenon, a distinction that is important

to bear in mind when issues related to

the place of women in Buddhism are discussed.

Study after study has shown that mainstream

Buddhism, both lay and monastic, has

adapted itself thoroughly to the various societies into which it has been introduced -- so

thoroughly that the original teachings

seem in some cases to have been completely distorted. From

the earliest centuries of the tradition on up to the present,

groups who feel inspired by the

Buddha's teachings, but who prefer to adapt

those teachings to their own ends rather than adapting themselves

to the teachings, have engaged in

creating what might be called designer

Buddhism. This accounts for the

wide differences we find when we

compare, say, Japanese Buddhism, Tibetan, and Thai, and for the variety of social roles to which many women

Buddhists in different countries have

found themselves relegated.

The true practice of Buddhism, though, has

always been counter-cultural, even in

nominally Buddhist societies. Society's main aim, no matter where, is its own

perpetuation. Its cultural values are designed to keep its members

useful and productive -- either

directly or indirectly -- in the on-going economy. Most

religions allow themselves to become domesticated to these values by stressing altruism as the highest religious

impulse, and mainstream Buddhism is no

different. Wherever it has spread, it

has become domesticated to the extent

that the vast majority of monastics as well

as lay followers devote themselves to social services of one form

or another, measuring their personal

spiritual worth in terms of how well

they have loved and served others.

However, the actual practice enjoined by

the Buddha does not place such a high

value on altruism at all. In fact, he

gave higher praise to those who work

exclusively for their own spiritual welfare than to those who sacrifice their spiritual welfare

for the the welfare of others

(Anguttara Nikaya, Book of Fours, Sutta 95) -- a teaching that the mainstream, especially in Mahayana

traditions, has tended to

suppress. The true path of

practice pursues happiness through social

withdrawal, the goal being an undying happiness found exclusively within, totally transcending the world, and

not necessarily expressed in any social

function. People who have attained the

goal may teach the path of practice to

others, or they may not. Those who do

are considered superior to those who

don't, but those who don't are in turn

said to be superior to those who teach without having attained the goal themselves. Thus individual attainment, rather than

social function, is the true measure of

a person's worth.

Mainstream Buddhism, because it can become

so domesticated, often seems to act at

cross-purposes to the actual practice of Buddhism. Women sense this primarily in the fact that

they do not have the same opportunities

for ordination that men do, and that they tend to be discouraged from pursuing the opportunities

that are available to them. The Theravadin Bhikkhuni Sangha, the nuns'

order founded by the Buddha, died out

because of war and famine almost a millennium ago, and the Buddha provided no mechanism for its

revival. (The same holds true for the Bhikkhu Sangha, or monks'

order. If it ever dies out, there is no way it can be revived.) Thus the only ordination opportunities open to women in Theravadin

countries are as lay nuns, observing

eight or ten precepts.

Because there is no formal organization for

the lay nuns, their status and

opportunities for practice vary widely from location to location.

In Thailand, the situation is most favorable in Rajburi and the neighboring province of Phetburi, both

of which -- perhaps because of the

influence of Mon culture in the area -- have a long tradition of highly-respected independent nunneries. Even there, though, the quality of instruction varies widely with the

nunnery, and many women find that they

prefer the opportunities for practice offered in nuns' communities affiliated with monasteries,

which is the basic pattern in other

parts of Thailand.

The opportunities that monasteries offer

for lay nuns to practice -- in terms of

available free time and the quality of the instruction given -- again vary widely from place to

place. One major drawback to nuns' communities affiliated with

monasteries is that the nuns are

relegated to a status clearly secondary to that of the monks, but

in the better monasteries this is

alleviated to some extent by the

Buddhist teachings on hierarchy:

that it is a mere social convention,

designed to streamline the decision-making process in the community, and based on morally neutral criteria so

that one's place in the hierarchy is

not an indication of one's worth as a person.

Of course there are sexist monks who

mistake the privileged position of men

as an indication of supposed male superiority, but fortunately nuns do not take vows of obedience and are

free to change communities if they find

the atmosphere oppressive. In the better

monasteries, nuns who have advanced far

in the practice are publicly recognized by

the abbots and can develop large personal followings. At present, for instance, one of the most active Dhamma

teachers in Bangkok is a woman, Amara

Malila, who abandoned her career as a medical doctor for a life in a nun's community connected with

one of the meditation monasteries in

the Northeast. After several years of

practice she began teaching, with the

blessings of the abbot, and now has a healthy

shelf of books to her name. Such

individuals, though, are a rarity, and

many lay nuns find themselves relegated to a celibate version of a housewife's life -- considerably freer in

their eyes than the life of an actual

housewife, but still far from conducive to the full-time practice of the Buddhist path.

Although the opportunities for women to

practice in Thailand are far from

ideal, it should also be noted that mainstream Buddhism often discourages men from practicing as

well. Opportunities for ordination are widely available to men, but it is a

rare monk who finds himself encouraged

to devote himself entirely to the practice.

In village monasteries, monks

have long been pressured to study medicine so that they can act as the village doctors or to

study astrology to become personal counselors. Both of these activities are forbidden by

the disciplinary rules, but are very

popular with the laity -- so popular

that until recent times a village monk who did not take up either

of these vocations was regarded as

shirking his duties. Scholarly

monks in the cities have long been told

that the path to //nibbana// is no

longer open, that full-time practice would be futile, and that a life devoted to administrative duties, with

perhaps a little meditation on the

side, is the most profitable use of one's monastic career.

On top of this, parents who encourage their

sons from early childhood to take

temporary ordination often pressure them to disrobe soon after ordination if they show any

inclination to stay in the monkhood

permanently and abandon the family business.

Even families who are happy to

have their sons stay in the monkhood often discourage them from enduring the hardships of a

meditator's life in the forest.

In some cases the state of mainstream Buddhism

has become so detrimental to the

practice that institutional reforms have been

attempted. In the Theravada

tradition, such reforms have succeeded

only if introduced from the top down, when senior monks have

received the support of the political

powers that be. The Canonical

example for this pattern is the First

Council, called with royal patronage in

the first year after the Buddha's passing away, for the express purpose of standardizing the record of the

Buddha's teachings for posterity. During the days of absolute monarchy, reforms

that followed this pattern could be

quite thorough-going and on occasion

were nothing short of draconian.

In more recent years, though, they

have been much more limited in scope, gaining a measure of success only when presented not as impositions but

as opportunities: access to more reliable texts, improved standards

and facilities for education, and

greater support for stricter observance of the

disciplinary rules. And, of

course, however such reforms may be

carried out, they are largely limited to externals, because the attainment of the Deathless is not something

that can be decreed by legislative

fiat.

A modern example of such a reform movement

is the Lay Nun Association of Thailand,

an attempt to provide an organizational

structure for all lay nuns throughout the country, sponsored by Her Majesty the Queen and senior monks in the

national hierarchy. This has succeeded chiefly in providing improved

educational opportunities for a

relatively small number of nuns, while its organizational aims have been something of a failure. Even though the association is run by highly educated nuns, most of the nuns I

know personally have avoided joining it

because they do not find the leaders personally inspiring and because they feel they would

be sacrificing their independence for

no perceivable benefit. This view may be

based on a common attitude in the

outlying areas of Thailand: the less

contact with the bureaucratic powers at

the center, the better.

As for confrontational reforms introduced

from the bottom up, these have never

been sanctioned by the tradition, and Theravadin history has no record of their ever succeeding. The only such reform mentioned in the Canon was Devadatta's

attempted schism, introduced as a

reform to tighten up the disciplinary rules.

The Canon treats his attempt in

such strongly negative terms that its memory is still very much alive in the Theravada mind set, making

the vast majority of Buddhists

reluctant to take up with confrontational reforms no matter how reasonable they might seem. And with good reason: Anyone who has to fight to have his/her ideas accepted

inevitably loses touch with the qualities

of dispassion, self-effacement, unentanglement with others, contentment with little, and

seclusion -- qualities the Buddha set

forth as the litmus test for gauging whether or not a proposed course of action, and the person proposing

it, were in accordance with the

Dhamma.

In addition, there have been striking

instances where people have proposed

religious reforms as a camouflage for their political ambitions, leaving their followers in a

lurch when their ambitions are thwarted. And even in cases where a confrontational

reformer seems basically altruistic at

heart, he or she tends to play up the social

benefits to be gained from the proposed reform in the effort to win support, thus compromising the relationship

of the reform to true practice. Experiences with cases such as this have

tended to make Theravadin Buddhists in

general leery of confrontational reforms.

Thus, given the limited opportunities for

institutional reform, the only course

left open to those few men and women prepared to break the bonds of mainstream Buddhism in their

determination to practice is to follow

the example of the Buddha himself by engaging in what might be called personal or independent reform: to reject the general values of society, go off on their own, put up with

society's disapproval and the hardships

of living on the frontier, and search for whatever reliable meditation teachers may be living

and practicing outside of the

mainstream. If no such teachers exist,

individuals intent on practice must

strike out on their own, adhering as closely as they can to the teachings in the texts -- to keep

themselves from being led astray by

their own defilements -- and taking refuge in the example of the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha in a radical

way.

In a sense, there is a sort of folk wisdom

to this arrangement. Anyone who would

take on the practice only when assured of comfortable material support, status, and praise --

which the Buddha called the baits of

the world -- would probably not be up to the sacrifices and self-discipline the practice inherently

entails.

Thus from the perspective of the practice,

mainstream Buddhism serves the function

of inspiring individuals truly intent on the

practice to leave the mainstream and to go into the forest, which

was where the religion was originally

discovered. As for those who prefer to stay in society, the mainstream meets

their social/religious needs while at

the same time making them inclined to view those who leave society in search of the Dhamma with some

measure of awe and respect, rather than

viewing them simply as drop-outs.

What this has meant historically is that

the true practice of Buddhism has

hovered about the edges of society and history -- or, from another perspective, that the history

of Buddhism has hovered about the edges

of the practice. When we look at the

historical record after the first

generation of the Buddha's disciples, we find

only a few anecdotal references to practicing monks or nuns. The only

teachers recorded were scholarly monks, participants in

controversies, and missionaries. Some people at present have taken the silence

on the nuns as an indication that there

were no prominent nun teachers after

the first generation of disciples.

However, inscriptions at the

Theravada stupa at Sanci in India list nuns among the prominent donors to its construction, and this would have

been possible only if the nuns had

large personal followings. Thus it seems

fair to assume that there were

prominent nun teachers, but that they were devoted to meditation rather than scholarship, and that

-- like the monks devoted to meditation

-- their names and teachings slipped through the cracks in the historical record inasmuch as true

success at meditation is something that

historians are in no position to judge.

So, for the period from Canonical up to

modern times, one can only make

conjectures about the opportunities for practice open to men and women at any particular time. Still, based on observations of the situation in Thailand before Western

influences made themselves strongly

felt, the following dynamic seems likely:

Meditation traditions tend to

last only two or three generations at most.

They are started by charismatic

pioneers willing to put up with the

hardships of clearing the Buddhist path.

Because the integrity of their

efforts takes years to be tested -- not all pioneers are free from delusion and dishonesty -- their role

requires great sacrifices. In fact, if

large-scale support comes too early, it may abort the movement.

If, over time, the pioneers do embody the practice faithfully, then as word of their teachings

and practices spread, they begin to

attract a following of students and supporters.

With the arrival of support, the

hardships become less demanding; and as life

softens, so does the practice, and within a generation or two it

has deteriorated to the extent that it

no longer inspires support and

eventually dies out, together with any memory of the founder's teachings.

In some cases, before the tradition dies

out, its example may have a reforming

influence at large, shaming or inspiring the mainstream at least temporarily into becoming more

favorable to true practice. In other cases, the practice tradition may

influence only a limited circle and then

disappear without a ripple. For those

who benefit from it, of course, the

question of its historical repercussions is of

no real consequence. Even if only

one person has benefited by realizing

the Deathless, the tradition is a success.

At

present in Thailand we are watching this process work itself out in several strands, with the major

difference being that modern media have

given us a record of the teachings and practices of many figures in the various meditation traditions. Among the monks, the most influential practice tradition is the Forest

Tradition, which was started against

great odds at the end of the last century by Phra Ajaan Sao Kantasilo and Phra Ajaan Mun

Bhuridatto, sons of peasants, at a time

when the central Thai bureaucracy was very active in stamping out independent movements of any

sort, political or religious. We have no direct record of Ajaan Sao's

teachings, only a booklet or two of

Ajaan Mun's, but volume upon volume of their

students' teachings. Among women,

the major practice tradition is Upasika

Kee Nanayon's. Although she herself has

passed away, the women at her center

still listen to her tapes nightly and keep her

teachings alive throughout society by printing and reprinting books

of her talks for Distribution.

Both traditions are fragile: The Forest Tradition is showing signs that its very popularity may soon lead to

its demise, and the women at Khao Suan

Luang are faced with the problem of seeing how long they can maintain their standard of practice without

charismatic leadership. On top of

this, the arrival of the mass media -- and especially television with its tendency to make image

more consequential than substance, and

personality more important than character -- is sure to change the dynamic of Buddhist mainstream

and the practice, not necessarily for

the better. Still, both traditions have

at least left a record -- part of which

is presented in this book -- to inspire

future generations and to show how the Buddhist path of practice

may be reopened by anyone, male or

female, no matter what forms of

designer Buddhism may take over the mainstream and inevitably lead

it astray.

* * * * * * * *