I Ching

Title page of a Song dynasty (c. 1100) edition of the I Ching | |

| Original title | 易 |

|---|---|

| Country | Zhou dynasty (China) |

| Language | Old Chinese |

| Genre | Divination, cosmology |

| Published | Late 9th century BC |

Original text | 易 at Chinese Wikisource |

| I Ching Book of Changes / Classic of Changes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

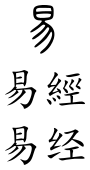

"I (Ching)" in seal script (top),[note 1] Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 易經 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 易经 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Yì Jīng | ||

| Literal meaning | "Classic of Changes" | ||

| |||

The I Ching or Yi Jing (Chinese: 易經, Mandarin: [î tɕíŋ] (![]() listen)), usually translated as Book of Changes or Classic of Changes, is an ancient Chinese divination text and among the oldest of the Chinese classics. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou period (1000–750 BC), the I Ching was transformed over the course of the Warring States and early imperial periods (500–200 BC) into a cosmological text with a series of philosophical commentaries known as the "Ten Wings".[1] After becoming part of the Five Classics in the 2nd century BC, the I Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of East Asian philosophical thought.[2]

listen)), usually translated as Book of Changes or Classic of Changes, is an ancient Chinese divination text and among the oldest of the Chinese classics. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou period (1000–750 BC), the I Ching was transformed over the course of the Warring States and early imperial periods (500–200 BC) into a cosmological text with a series of philosophical commentaries known as the "Ten Wings".[1] After becoming part of the Five Classics in the 2nd century BC, the I Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of East Asian philosophical thought.[2]

As a divination text, the I Ching is used for a traditional Chinese form of cleromancy known as I Ching divination, in which

bundles of yarrow stalks are manipulated to produce sets of six apparently random numbers ranging from 6 to 9. Each of the 64 possible sets corresponds to a hexagram, which can be looked up in the text. The hexagrams are arranged in an order known as the King Wen sequence.

The interpretation of the readings found in the I Ching has been endlessly discussed and debated over the centuries.

Many commentators have used the book symbolically, often to provide guidance for moral decision making as informed by Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. The hexagrams themselves have often acquired cosmological significance and been paralleled with many other traditional names for the processes of change such as yin and yang and Wu Xing.

The divination text: Zhou yi[edit]

History[edit]

The core of the I Ching is a Western Zhou divination text called the Changes of Zhou (Chinese: 周易; pinyin: Zhōu yì).[3] Various modern scholars suggest dates ranging between the 10th and 4th centuries BC for the assembly of the text in approximately its current form.[4] Based on a comparison of the language of the Zhou yi with dated bronze inscriptions, the American sinologist Edward Shaughnessy dated its compilation in its current form to the last quarter of the 9th century BC, during the early decades of the reign of King Xuan of Zhou (r. c. 827 – 782 BC).[5] A copy of the text in the Shanghai Museum corpus of bamboo and wooden slips (discovered in 1994) shows that the Zhou yi was used throughout all levels of Chinese society in its current form by 300 BC, but still contained small variations as late as the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BC).[6] It is possible that other divination systems existed at this time; the Rites of Zhou name two other such systems, the Lianshan and the Guicang.[7]

Name and authorship[edit]

The name Zhou yi literally means the "changes" (易; Yì) of the Zhou dynasty. The "changes" involved have been interpreted as the transformations of hexagrams, of their lines, or of the numbers obtained from the divination.[8] Feng Youlan proposed that the word for "changes" originally meant "easy", as in a form of divination easier than the oracle bones, but there is little evidence for this. There is also an ancient folk etymology that sees the character for "changes" as containing the sun and moon, the cycle of the day. Modern Sinologists believe the character to be derived either from an image of the sun emerging from clouds, or from the content of a vessel being changed into another.[9]

The Zhou yi was traditionally ascribed to the Zhou cultural heroes King Wen of Zhou and the Duke of Zhou, and was also associated with the legendary world ruler Fu Xi.[10] According to the canonical Great Commentary, Fu Xi observed the patterns of the world and created the eight trigrams (八卦; bāguà), "in order to become thoroughly conversant with the numinous and bright and to classify the myriad things." The Zhou yi itself does not contain this legend and indeed says nothing about its own origins.[11] The Rites of Zhou, however, also claims that the hexagrams of the Zhou yi were derived from an initial set of eight trigrams.[12] During the Han dynasty there were various opinions about the historical relationship between the trigrams and the hexagrams.[13] Eventually, a consensus formed around 2nd-century AD scholar Ma Rong's attribution of the text to the joint work of Fu Xi, King Wen of Zhou, the Duke of Zhou, and Confucius, but this traditional attribution is no longer generally accepted.[14]

Structure[edit]

The basic unit of the Zhou yi is the hexagram (卦 guà), a figure composed of six stacked horizontal lines (爻 yáo). Each line is either broken or unbroken. The received text of the Zhou yi contains all 64 possible hexagrams, along with the hexagram's name (卦名 guàmíng), a short hexagram statement (彖 tuàn),[note 2] and six line statements (爻辭 yáocí).[note 3] The statements were used to determine the results of divination, but the reasons for having two different methods of reading the hexagram are not known, and it is not known why hexagram statements would be read over line statements or vice versa.[15]

The book opens with the first hexagram statement, yuán hēng lì zhēn (Chinese: 元亨利貞). These four words, translated traditionally by James Legge as "originating and penetrating, advantageous and firm," are often repeated in the hexagram statements and were already considered an important part of I Ching interpretation in the 6th century BC. Edward Shaughnessy describes this statement as affirming an "initial receipt" of an offering, "beneficial" for further "divining".[16] The word zhēn (貞, ancient form ![]() ) was also used for the verb "divine" in the oracle bones of the late Shang dynasty, which preceded the Zhou. It also carried meanings of being or making upright or correct, and was defined by the Eastern Han scholar Zheng Xuan as "to enquire into the correctness" of a proposed activity.[17]

) was also used for the verb "divine" in the oracle bones of the late Shang dynasty, which preceded the Zhou. It also carried meanings of being or making upright or correct, and was defined by the Eastern Han scholar Zheng Xuan as "to enquire into the correctness" of a proposed activity.[17]

The names of the hexagrams are usually words that appear in their respective line statements, but in five cases (2, 9, 26, 61, and 63) an unrelated character of unclear purpose appears. The hexagram names could have been chosen arbitrarily from the line statements,[18] but it is also possible that the line statements were derived from the hexagram names.[19] The line statements, which make up most of the book, are exceedingly cryptic. Each line begins with a word indicating the line number, "base, 2, 3, 4, 5, top", and either the number 6 for a broken line, or the number 9 for a whole line. Hexagrams 1 and 2 have an extra line statement, named yong.[20] Following the line number, the line statements may make oracular or prognostic statements.[21] Some line statements also contain poetry or references to historical events.[22]

Usage[edit]

Archaeological evidence shows that Zhou dynasty divination was grounded in cleromancy, the production of seemingly random numbers to determine divine intent.[23] The Zhou yi provided a guide to cleromancy that used the stalks of the yarrow plant, but it is not known how the yarrow stalks became numbers, or how specific lines were chosen from the line readings.[24] In the hexagrams, broken lines were used as shorthand for the numbers 6 (六) and 8 (八), and solid lines were shorthand for values of 7 (七) and 9 (九). The Great Commentary contains a late classic description of a process where various numerological operations are performed on a bundle of 50 stalks, leaving remainders of 6 to 9.[25] Like the Zhou yi itself, yarrow stalk divination dates to the Western Zhou period, although its modern form is a reconstruction.[26]

The ancient narratives Zuo zhuan and Guoyu contain the oldest descriptions of divination using the Zhou yi. The two histories describe more than twenty successful divinations conducted by professional soothsayers for royal families between 671 BC and 487 BC. The method of divination is not explained, and none of the stories employ predetermined commentaries, patterns, or interpretations. Only the hexagrams and line statements are used.[27] By the 4th century BCE, the authority of the Zhou yi was also cited for rhetorical purposes, without relation to any stated divination.[28] The Zuo zhuan does not contain records of private individuals, but Qin dynasty records found at Shuihudi show that the hexagrams were privately consulted to answer questions such as business, health, children, and determining lucky days.[29]

The most common form of divination with the I Ching in use today is a reconstruction of the method described in these histories, in the 300 BC Great Commentary, and later in the Huainanzi and the Lunheng. From the Great Commentary's description, the Neo-Confucian Zhu Xi reconstructed a method of yarrow stalk divination that is still used throughout the Far East. In the modern period, Gao Heng attempted his own reconstruction, which varies from Zhu Xi in places.[30] Another divination method, employing coins, became widely used in the Tang dynasty and is still used today. In the modern period; alternative methods such as specialized dice and cartomancy have also appeared.[31]

In the Zuo zhuan stories, individual lines of hexagrams are denoted by using the genitive particle zhi (之), followed by the name of another hexagram where that specific line had another form. In later attempts to reconstruct ancient divination methods, the word zhi was interpreted as a verb meaning "moving to", an apparent indication that hexagrams could be transformed into other hexagrams. However, there are no instances of "changeable lines" in the Zuo zhuan. In all 12 out of 12 line statements quoted, the original hexagrams are used to produce the oracle.[32]

The classic: I Ching[edit]

In 136 BC, Emperor Wu of Han named the Zhou yi "the first among the classics", dubbing it the Classic of Changes or I Ching. Emperor Wu's placement of the I Ching among the Five Classics was informed by a broad span of cultural influences that included Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism, yin-yang cosmology, and Wu Xing physical theory.[33] While the Zhou yi does not contain any cosmological analogies, the I Ching was read as a microcosm of the universe that offered complex, symbolic correspondences.[34] The official edition of the text was literally set in stone, as one of the Xiping Stone Classics.[35] The canonized I Ching became the standard text for over two thousand years, until alternate versions of the Zhou yi and related texts were discovered in the 20th century.[36]

Ten Wings[edit]

Part of the canonization of the Zhou yi bound it to a set of ten commentaries called the Ten Wings. The Ten Wings are of a much later provenance than the Zhou yi, and are the production of a different society. The Zhou yi was written in Early Old Chinese, while the Ten Wings were written in a predecessor to Middle Chinese.[37] The specific origins of the Ten Wings are still a complete mystery to academics.[38] Regardless of their historical relation to the text, the philosophical depth of the Ten Wings made the I Ching a perfect fit to Han period Confucian scholarship.[39] The inclusion of the Ten Wings reflects a widespread recognition in ancient China, found in the Zuo zhuan and other pre-Han texts, that the I Ching was a rich moral and symbolic document useful for more than professional divination.[40]

Arguably the most important of the Ten Wings is the Great Commentary (Dazhuan) or Xi ci, which dates to roughly 300 BC.[note 4] The Great Commentary describes the I Ching as a microcosm of the universe and a symbolic description of the processes of change. By partaking in the spiritual experience of the I Ching, the Great Commentary states, the individual can understand the deeper patterns of the universe.[25] Among other subjects, it explains how the eight trigrams proceeded from the eternal oneness of the universe through three bifurcations.[41] The other Wings provide different perspectives on essentially the same viewpoint, giving ancient, cosmic authority to the I Ching.[42] For example, the Wenyan provides a moral interpretation that parallels the first two hexagrams, 乾 (qián) and 坤 (kūn), with Heaven and Earth,[43] and the Shuogua attributes to the symbolic function of the hexagrams the ability to understand self, world, and destiny.[44] Throughout the Ten Wings, there are passages that seem to purposefully increase the ambiguity of the base text, pointing to a recognition of multiple layers of symbolism.[45]

The Great Commentary associates knowledge of the I Ching with the ability to "delight in Heaven and understand fate;" the sage who reads it will see cosmological patterns and not despair in mere material difficulties.[46] The Japanese word for "metaphysics", keijijōgaku (形而上学; pinyin: xíng ér shàng xué) is derived from a statement found in the Great Commentary that "what is above form [xíng ér shàng] is called Dao; what is under form is called a tool".[47] The word has also been borrowed into Korean and re-borrowed back into Chinese.

The Ten Wings were traditionally attributed to Confucius, possibly based on a misreading of the Records of the Grand Historian.[48] Although it rested on historically shaky grounds, the association of the I Ching with Confucius gave weight to the text and was taken as an article of faith throughout the Han and Tang dynasties.[49] The I Ching was not included in the burning of the Confucian classics, and textual evidence strongly suggests that Confucius did not consider the Zhou yi a "classic". An ancient commentary on the Zhou yi found at Mawangdui portrays Confucius as endorsing it as a source of wisdom first and an imperfect divination text second.[50] However, since the Ten Wings became canonized by Emperor Wu of Han together with the original I Ching as the Zhou Yi, it can be attributed to the positions of influence from the Confucians in the government.[51] Furthermore, the Ten Wings tends to use diction and phrases such as "the master said", which was previously commonly seen in the Analects, thereby implying the heavy involvement of Confucians in its creation as well as institutionalization.[51]

Hexagrams[edit]

In the canonical I Ching, the hexagrams are arranged in an order dubbed the King Wen sequence after King Wen of Zhou, who founded the Zhou dynasty and supposedly reformed the method of interpretation. The sequence generally pairs hexagrams with their upside-down equivalents, although in eight cases hexagrams are paired with their inversion.[52] Another order, found at Mawangdui in 1973, arranges the hexagrams into eight groups sharing the same upper trigram. But the oldest known manuscript, found in 1987 and now held by the Shanghai Library, was almost certainly arranged in the King Wen sequence, and it has even been proposed that a pottery paddle from the Western Zhou period contains four hexagrams in the King Wen sequence.[53] Whichever of these arrangements is older, it is not evident that the order of the hexagrams was of interest to the original authors of the Zhou yi. The assignment of numbers, binary or decimal, to specific hexagrams, is a modern invention.[54]

Yin and yang are represented by broken and solid lines: yin is broken (⚋) and yang is solid (⚊). Different constructions of three yin and yang lines lead to eight trigrams (八卦) namely, Qian (乾, ☰), Dui (兌, ☱), Li (離, ☲), Zhen (震, ☳), Xun (巽, ☴), Kan (坎, ☵), Gen (艮, ☶), and Kun (坤, ☷).

The different combinations of the two trigrams lead to 64 hexagrams.

The following table numbers the hexagrams in King Wen order.

Interpretation and influence[edit]

The sinologist Michael Nylan describes the I Ching as the best-known Chinese book in the world.[55] In East Asia, it is a foundational text for the Confucian and Daoist philosophical traditions, while in the West, it attracted the attention of Enlightenment intellectuals and prominent literary and cultural figures.

Eastern Han and Six Dynasties[edit]

During the Eastern Han, I Ching interpretation divided into two schools, originating in a dispute over minor differences between different editions of the received text.[56] The first school, known as New Text criticism, was more egalitarian and eclectic, and sought to find symbolic and numerological parallels between the natural world and the hexagrams. Their commentaries provided the basis of the School of Images and Numbers. The other school, Old Text criticism, was more scholarly and hierarchical, and focused on the moral content of the text, providing the basis for the School of Meanings and Principles.[57] The New Text scholars distributed alternate versions of the text and freely integrated non-canonical commentaries into their work, as well as propagating alternate systems of divination such as the Taixuanjing.[58] Most of this early commentary, such as the image and number work of Jing Fang, Yu Fan and Xun Shuang, is no longer extant.[59] Only short fragments survive, from a Tang dynasty text called Zhou yi jijie.[60]

With the fall of the Han, I Ching scholarship was no longer organized into systematic schools. The most influential writer of this period was Wang Bi, who discarded the numerology of Han commentators and integrated the philosophy of the Ten Wings directly into the central text of the I Ching, creating such a persuasive narrative that Han commentators were no longer considered significant. A century later Han Kangbo added commentaries on the Ten Wings to Wang Bi's book, creating a text called the Zhouyi zhu. The principal rival interpretation was a practical text on divination by the soothsayer Guan Lu.[61]

Tang and Song dynasties[edit]

At the beginning of the Tang dynasty, Emperor Taizong of Tang ordered Kong Yingda to create a canonical edition of the I Ching. Choosing Wang Bi's 3rd-century "Annotated Zhou-dynasty (Book of) Changes" (Zhōuyì Zhù; 周易注) as the official commentary, he added to it further commentary drawing out the subtler details of Wang Bi's explanations. The resulting work, the "Right Meaning of the Zhou-dynasty (Book of) Changes" (Zhōuyì Zhèngyì; 周易正義), became the standard edition of the I Ching through the Song dynasty.[62]

By the 11th century, the I Ching was being read as a work of intricate philosophy, as a jumping-off point for examining great metaphysical questions and ethical issues.[63] Cheng Yi, patriarch of the Neo-Confucian Cheng–Zhu school, read the I Ching as a guide to moral perfection. He described the text as a way to for ministers to form honest political factions, root out corruption, and solve problems in government.[64]

The contemporary scholar Shao Yong rearranged the hexagrams in a format that resembles modern binary numbers, although he did not intend his arrangement to be used mathematically.[65] This arrangement, sometimes called the binary sequence, later inspired Leibniz.

Neo-Confucianism[edit]

The 12th century Neo-Confucian Zhu Xi, cofounder of the Cheng–Zhu school, criticized both of the Han dynasty lines of commentary on the I Ching, saying that they were one-sided. He developed a synthesis of the two, arguing that the text was primarily a work of divination that could be used in the process of moral self-cultivation, or what the ancients called "rectification of the mind" in the Great Learning. Zhu Xi's reconstruction of I Ching yarrow stalk divination, based in part on the Great Commentary account, became the standard form and is still in use today.[66]

As China entered the early modern period, the I Ching took on renewed relevance in both Confucian and Daoist studies. The Kangxi Emperor was especially fond of the I Ching and ordered new interpretations of it.[67] Qing dynasty scholars focused more intently on understanding pre-classical grammar, assisting the development of new philological approaches in the modern period.[68]

East Asia[edit]

Like the other Chinese classics, the I Ching was an influential text across East Asia.

In 1557, the Korean Neo-Confucianist philosopher Yi Hwang produced one of the most influential I Ching studies of the early modern era, claiming that the spirit was a principle (li) and not a material force (qi). Hwang accused the Neo-Confucian school of having misread Zhu Xi. His critique proved influential not only in Korea but also in Japan.[69]

Other than this contribution, the I Ching—known in Korean as the Yeok Gyeong (역경)—was not central to the development of Korean Confucianism, and by the 19th century, I Ching studies were integrated into the silhak reform movement.[70]

In medieval Japan, secret teachings on the I Ching—known in Japanese as the Eki Kyō (易経)—were publicized by Rinzai Zen master Kokan Shiren and the Shintoist Yoshida Kanetomo during the Kamakura era.[71] I Ching studies in Japan took on new importance during the Edo period, during which over 1,000 books were published on the subject by over 400 authors. The majority of these books were serious works of philology, reconstructing ancient usages and commentaries for practical purposes. A sizable minority focused on numerology, symbolism, and divination.[72] During this time, over 150 editions of earlier Chinese commentaries were reprinted across Edo Japan, including several texts that had become lost in China.[73] In the early Edo period, Japanese writers such as Itō Jinsai, Kumazawa Banzan, and Nakae Toju ranked the I Ching the greatest of the Confucian classics.[74]

Many writers attempted to use the I Ching to explain Western science in a Japanese framework. One writer, Shizuki Tadao, even attempted to employ Newtonian mechanics and the Copernican principle within an I Ching cosmology.[75] This line of argument was later taken up in China by the Qing politician Zhang Zhidong.[76]

Early European[edit]

Leibniz, who was corresponding with Jesuits in China, wrote the first European commentary on the I Ching in 1703. He argued that it proved the universality of binary numbers and theism, since the broken lines, the "0" or "nothingness", cannot become solid lines, the "1" or "oneness", without the intervention of God.[77] This was criticized by Hegel, who proclaimed that binary system and Chinese characters were "empty forms" that could not articulate spoken words with the clarity of the Western alphabet.[78] In their commentary, I Ching hexagrams and Chinese characters were conflated into a single foreign idea, sparking a dialogue on Western philosophical questions such as universality and the nature of communication. The usage of binary in relation to the I Ching was central to Leibniz's characteristica universalis, or universal language, which in turn inspired the standards of Boolean logic and for Gottlob Frege to develop predicate logic in the late 19th century.

In the 20th century, Jacques Derrida identified Hegel's argument as logocentric, but accepted without question Hegel's premise that the Chinese language cannot express philosophical ideas.[79]

Modern[edit]

After the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, the I Ching was no longer part of mainstream Chinese political philosophy, but it maintained cultural influence as China's most ancient text. Borrowing back from Leibniz, Chinese writers offered parallels between the I Ching and subjects such as linear algebra and logic in computer science, aiming to demonstrate that ancient Chinese cosmology had anticipated Western discoveries.[80]

The Sinologist Joseph Needham took the opposite opinion, arguing that the I Ching had actually impeded scientific development by incorporating all physical knowledge into its metaphysics. However with the advent of quantum mechanics, physicist Niels Bohr credited inspiration from the Yin and Yang symbolisms in using intuition to interpret the new field, which disproved principles from older Western classical mechanics. The principle of complementarity heavily used concepts from the I Ching as mentioned in his writings.[81]

The psychologist Carl Jung took interest in the possible universal nature of the imagery of the I Ching, and he introduced an influential German translation by Richard Wilhelm by discussing his theories of archetypes and synchronicity.[82]

Jung wrote, "Even to the most biased eye, it is obvious that this book represents one long admonition to careful scrutiny of one's own character, attitude, and motives."[83] The book had a notable impact on the 1960s counterculture and on 20th century cultural figures such as Philip K. Dick, John Cage, Jorge Luis Borges, Terence McKenna and Hermann Hesse.[84] It also inspired the 1968 song While My Guitar Gently Weeps by The Beatles.

The modern period also brought a new level of skepticism and rigor to I Ching scholarship. Li Jingchi spent several decades producing a new interpretation of the text, which was published posthumously in 1978. Modern data scientists including Alex Liu proposed to represent and develop I Ching methods with data science 4E framework and latent variable approaches for a more rigorous representation and interpretation of I Ching.[85] Gao Heng, an expert in pre-Qin China, reinvestigated its use as a Zhou dynasty oracle. Edward Shaughnessy proposed a new dating for the various strata of the text.[86] New archaeological discoveries have enabled a deeper level of insight into how the text was used in the centuries before the Qin dynasty. Proponents of newly reconstructed Western Zhou readings, which often differ greatly from traditional readings of the text, are sometimes called the "modernist school".[87]

In Fiction[edit]

The I Ching features significantly in Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle (an alternate reality novel where the Axis Powers won World War II), where various characters in the Japanese-controlled portion of America base their decisions on what it tells them.

I Ching is also in Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials where it guides the physicist Mary Malone on her interactions with Dust/Dark Matter and leads her to another dimension.

The episode "Grand Deceptions" (episode 4, season 8) of Columbo show the Yi Jing.

In The Long Dark Teatime of the Soul by Douglas Adams, Dirk Gently buys an electronic calculator that contains a badly-translated version of the I Ching, and uses it to decide if he should buy a new fridge.

In the Discworld novel Mort, Cutwell the wizard uses a similar divination technique called the Ching-Aling.

Translations[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

The I Ching has been translated into Western languages dozens of times. The earliest published complete translation of the I Ching into a Western language was a Latin translation done in the 1730s by the French Jesuit missionary Jean-Baptiste Régis that was published in Germany in the 1830s.[88]

Historically, the most influential Western-language I Ching translation was Richard Wilhelm's 1923 German translation, which was translated into English in 1950 by Cary Baynes.[89] Although Thomas McClatchie and James Legge had both translated the text in the 19th century, the text gained significant traction during the counterculture of the 1960s, with the translations of Wilhelm and John Blofeld attracting particular interest.[90] Richard Rutt's 1996 translation incorporated much of the new archaeological and philological discoveries of the 20th century. Gregory Whincup's 1986 translation also attempts to reconstruct Zhou period readings.[91]

The most commonly used English translations of the I Ching are:[88]

- Legge, James (1882). The Yî King. In Sacred Books of the East, vol. XVI. 2nd edition (1899), Oxford: Clarendon Press; reprinted numerous times.

- Wilhelm, Richard (1924, 1950). The I Ching or Book of Changes. Cary Baynes, trans. Bollingen Series 19. Introduction by Carl G. Jung. New York: Pantheon Books. 3rd edition (1967), Princeton: Princeton University Press; reprinted numerous times.

Other notable English translations include:

- McClatchie, Thomas (1876). A Translation of the Confucian Yi-king. Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press.

- Blofeld, John (1965). The Book of Changes: A New Translation of the Ancient Chinese I Ching. New York: E. P. Dutton.

- Lynn, Richard John (1994). The Classic of Changes. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08294-0.

- Rutt, Richard (1996). The Book of Changes (Zhouyi): A Bronze Age Document. Richmond: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-0467-1.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1996). I Ching: The Classic of Changes. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-36243-8.

- Huang, Alfred (1998). The Complete I Ching. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions Press. ISBN 0-89281-656-2.

- Redmond, Geoffrey (2017). The I Ching (Book of Changes): A Critical Translation of the Ancient Text. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4725-1413-4.

- Adler, Joseph A. (2020). The Original Meaning of the Yijing: Commentary on the Scripture of Change [by Zhu Xi]. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-19124-1.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b The *k-lˤeng (jing 經, "classic") appellation would not have been used until after the Han dynasty, after the core Old Chinese period.

- ^ The word tuàn (彖) refers to a four-legged animal similar to a pig. This is believed to be a gloss for "decision," duàn (斷). The modern word for a hexagram statement is guàcí (卦辭). Knechtges (2014), pp. 1881

- ^ Referred to as yao (繇) in the Zuo zhuan. Nielsen (2003), pp. 24, 290

- ^ The received text was rearranged by Zhu Xi. (Nielsen 2003, p. 258)

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Kern (2010), p. 17.

- ^ Redmond 2021; Adler 2022; chs. 1,6,7.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 22; Nelson 2011, p. 377; Hon 2005, p. 2; Shaughnessy 1983, p. 105; Raphals 2013, p. 337; Nylan 2001, p. 220; Redmond & Hon 2014, p. 37; Rutt 1996, p. 26.

- ^ Nylan (2001), p. 218.

- ^ Shaughnessy 1983, p. 219; Rutt 1996, pp. 32–33; Smith 2012, p. 22; Knechtges 2014, p. 1885.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, p. 282; Smith 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Rutt 1996, p. 26-7; Redmond & Hon 2014, pp. 106–9; Shchutskii 1979, p. 98.

- ^ Knechtges (2014), p. 1877.

- ^ Shaughnessy 1983, p. 106; Schuessler 2007, p. 566; Nylan 2001, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Shaughnessy (1999), p. 295.

- ^ Redmond & Hon (2014), pp. 54–5.

- ^ Shaughnessy (2014), p. 144.

- ^ Nielsen (2003), p. 7.

- ^ Nielsen 2003, p. 249; Shchutskii 1979, p. 133.

- ^ Rutt (1996), pp. 122–5.

- ^ Rutt 1996, pp. 126, 187–8; Shchutskii 1979, pp. 65–6; Shaughnessy 2014, pp. 30–35; Redmond & Hon 2014, p. 128.

- ^ Shaughnessy (2014), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Rutt 1996, p. 118; Shaughnessy 1983, p. 123.

- ^ Knechtges (2014), p. 1879.

- ^ Rutt (1996), pp. 129–30.

- ^ Rutt (1996), p. 131.

- ^ Knechtges (2014), pp. 1880–1.

- ^ Shaughnessy (2014), p. 14.

- ^ Smith (2012), p. 39.

- ^ a b Smith (2008), p. 27.

- ^ Raphals (2013), p. 129.

- ^ Rutt (1996), p. 173.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 43; Raphals 2013, p. 336.

- ^ Raphals (2013), pp. 203–212.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 27; Raphals 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Redmond & Hon (2014), pp. 257.

- ^ Shaughnessy 1983, p. 97; Rutt 1996, p. 154-5; Smith 2008, p. 26.

- ^ Smith (2008), p. 31-2.

- ^ Raphals (2013), p. 337.

- ^ Nielsen 2003, pp. 48–51; Knechtges 2014, p. 1889.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, passim; Smith 2008, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Rutt (1996), p. 39.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, p. 284; Smith 2008, pp. 31–48.

- ^ Smith (2012), p. 48.

- ^ Nylan (2001), p. 229.

- ^ Nielsen (2003), p. 260.

- ^ Smith (2008), p. 48.

- ^ Knechtges (2014), p. 1882.

- ^ Redmond & Hon (2014), pp. 151–2.

- ^ Nylan (2001), p. 221.

- ^ Nylan (2001), pp. 248–9.

- ^ Yuasa (2008), p. 51.

- ^ Peterson (1982), p. 73.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 27; Nielsen 2003, pp. 138, 211.

- ^ Shchutskii 1979, p. 213; Smith 2012, p. 46.

- ^ a b Adler, Joseph A. (April 2017). "Zhu Xi's Commentary on the Xicizhuan 繫辭傳 (Treatise on the Appended Remarks) Appendix of the Yijing 易經 (Scripture of Change)" (PDF).

- ^ Smith (2008), p. 37.

- ^ Shaughnessy (2014), pp. 52–3, 16–7.

- ^ Rutt (1996), pp. 114–8.

- ^ Nylan (2001), pp. 204–6.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 58; Nylan 2001, p. 45; Redmond & Hon 2014, p. 159.

- ^ Smith (2012), p. 76-8.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 76–9; Knechtges 2014, p. 1889.

- ^ Smith (2008), pp. 57, 67, 84–6.

- ^ Knechtges (2014), p. 1891.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 89–90, 98; Hon 2005, pp. 29–30; Knechtges 2014, p. 1890.

- ^ Hon 2005, pp. 29–33; Knechtges 2014, p. 1891.

- ^ Hon (2005), p. 144.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 128; Redmond & Hon 2014, p. 177.

- ^ Redmond & Hon (2014), p. 227.

- ^ Adler 2002, pp. v–xi; Smith 2008, p. 229; Adler 2020, pp. 9–16.

- ^ Smith (2008), p. 177.

- ^ Nielsen (2003), p. xvi.

- ^ Ng (2000b), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Ng (2000b), p. 65.

- ^ Ng (2000a), p. 7, 15.

- ^ Ng (2000a), pp. 22–25.

- ^ Ng (2000a), pp. 28–29.

- ^ Ng (2000a), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Ng (2000a), pp. 143–45.

- ^ Smith (2008), p. 197.

- ^ Nelson 2011, p. 379; Smith 2008, p. 204.

- ^ Nelson (2011), p. 381.

- ^ Nelson (2011), p. 383.

- ^ Smith (2008), p. 205.

- ^ Redmond & Hon (2014), p. 231.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 212; Redmond & Hon 2014, pp. 205–214.

- ^ Smith (2012), pp. 11, 198.

- ^ Smith (2012), pp. 11, 197–198.

- ^ "I Ching Methods Represented with Big Data Science". Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Knechtges (2014), pp. 1884–5.

- ^ Redmond & Hon 2014, p. 122ff; Shaughnessy 2014, passim.

- ^ a b Shaughnessy (1993), p. 225.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, p. 1; Redmond & Hon 2014, p. 239.

- ^ Smith (2012), pp. 198–9.

- ^ Redmond & Hon (2014), pp. 241–3.

Works cited[edit]

- Adler, Joseph A., trans. (2002). Introduction to the Study of the Classic of Change (I-hsüeh ch'i-meng). Provo, Utah: Global Scholarly Publications. ISBN 1-59267-334-1.

- Adler, Joseph A., trans. (2020). The Original Meaning of the Yijing: Commentary on the Scripture of Change. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-19124-1.

- Adler, Joseph A. (2022). The Yijing: A Guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-007246-9.

- Hon, Tze-ki 韓子奇 (2005). The Yijing and Chinese Politics: Classical Commentary and Literati Activism in the Northern Song Period, 960–1127. Albany: State Univ. of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-6311-7.

- Kern, Martin (2010). "Early Chinese literature, Beginnings through Western Han". In Owen, Stephen (ed.). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume 1: To 1375. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–115. ISBN 978-0-521-11677-0.

- Knechtges, David R. (2014). "Yi jing" 易經 [Classic of changes]. In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide. Vol. 3. Leiden: Brill Academic Pub. pp. 1877–1896. ISBN 978-90-04-27216-3.

- Nelson, Eric S. (2011). "The Yijing and Philosophy: From Leibniz to Derrida". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 38 (3): 377–396. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.2011.01661.x.

- Ng, Wai-ming 吳偉明 (2000a). The I Ching in Tokugawa Thought and Culture. Honolulu, HI: Association for Asian Studies and University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2242-0.

- Ng, Wai-ming (2000b). "The I Ching in Late-Choson Thought". Korean Studies. 24 (1): 53–68. doi:10.1353/ks.2000.0013. S2CID 162334992.

- Nielsen, Bent (2003). A Companion to Yi Jing Numerology and Cosmology : Chinese Studies of Images and Numbers from Han (202 BCE–220 CE) to Song (960–1279 CE). London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1608-4.

- Nylan, Michael (2001). The Five "Confucian" Classics. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-13033-3.

- Peterson, Willard J. (1982). "Making Connections: 'Commentary on the Attached Verbalizations' of the Book of Change". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 42 (1): 67–116. doi:10.2307/2719121. JSTOR 2719121.

- Raphals, Lisa (2013). Divination and Prediction in Early China and Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01075-8.

- Redmond, Geoffrey; Hon, Tze-Ki (2014). Teaching the I Ching. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976681-9.

- Redmond, Geoffrey (2021). "The Yijing in Early Postwar Counterculture in the West". In Ng, Wai-ming (ed.). The Making of the Global Yijing in the Modern World. Singapore: Springer. pp. 197–221. ISBN 978-981-33-6227-7.

- Rutt, Richard (1996). The Book of Changes (Zhouyi): A Bronze Age Document. Richmond: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-0467-1.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-1-4356-6587-3.

- Shaughnessy, Edward (1983). The composition of the Zhouyi (Ph.D. thesis). Stanford University.

- Shaughnessy, Edward (1993). "I Ching 易經 (Chou I 周易)". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley, CA: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute for East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 216–228. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Shaughnessy, Edward (1999). "Western Zhou History". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C.. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 292–351. ISBN 0-521-47030-7.

- Shaughnessy, Edward (2014). Unearthing the Changes: Recently Discovered Manuscripts of the Yi Jing (I Ching) and Related Texts. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-16184-8.

- Shchutskii, Julian (1979). Researches on the I Ching. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press. ISBN 0-691-09939-1.

- Smith, Richard J. (2008). Fathoming the Cosmos and Ordering the World: the Yijing (I Ching, or Classic of Changes) and its Evolution in China. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-2705-3.

- Smith, Richard J. (2012). The I Ching: A Biography. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14509-9.

- Yuasa, Yasuo (2008). Overcoming Modernity: Synchronicity and Image-thinking. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4356-5870-7.

External links[edit]

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 易經. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to I Ching. |

| Wikiversity has learning resources about I Ching oracle |

6

6