윌리엄 틴들

윌리엄 틴들(틴데일)(William Tyndale, 1494년~1536년 웨일스 슬림브리지 출신)은 영국의 종교인이다. 존 위클리프에게 영향을 받아 헬라어를 영어로 성경을 번역한 사람이다. 그는 영어 번역을 위해 독일로 건너가 비밀리에 번역작업을 했으며 기존에는 없던 새로운 단어를 만들기도 했다. 성경을 번역한 죄로 체포되어 1536년 10월6일 화형당했다. 킹 제임스 성경 영어 판의 70%가 틴데일의 성경에 근거한다. 그가 독일로 건너가서 동시대의 사람은 마틴 루터의 활동에 영감을 받은 것은 영국의 개혁운동이 외래의 영향을 통해 이루어진 가장 큰 이유로 이해된다.[1]

영국 캠브리지에는 그의 이름 가진 틴델하우스가 있는데 많은 전문학자들이 연구하고 발표하는 연구소로 유명한 곳이다.

생애[편집]

윌리엄 틴들은 1494년 글로스터에서 태어났다. 1510년 옥스퍼드 대학교에 입학하여 1515년 문학 석사학위를 받은 후 성경을 연구하기 위해 1519년 케임브리지로 옮겼다. 성경 연구를 통해 로마 가톨릭교회의 오류를 발견한 틴데일은 성경의 가르침에 따라 영국을 개혁하고자 하였다. 그는 성경을 "하나님의 말씀, 가장 진기한 보석, 지상에 남아 있는 가장 거룩한 유물이며, 신앙의 안내자요 지침서"라고 주장하였다.

틴데일은 성경 지식을 보급함으로 종교개혁이 가능하다고 믿고, 성경을 영어로 번역하고자 하였다. 그러나 당시에 성경을 번역하거나 일반인들이 읽는 것은 로마 교황청이 엄격에서히 금하는 일로 붙잡힐 경우 화형을 당하게 되었다. 틴들은 이러한 박해와 체포 위협 속에서도 유럽 대륙을 떠돌며, 라틴어가 아니라 히브리어와 그리스어 원전에 의한 번역 작업을 계속해 1526년 영어 신약성서를 완성하고 독일에서 인쇄해 영국으로 보냈다. 틴들은 그 후에도 구약성서 번역 작업을 계속했지만, 1535년 네덜란드에서 성경을 영어로 번역했다는 죄목 때문에 체포되었고, 다음해에 화형을 당한다.[2]

그의 사형 이후 엘리자베스 1세에 의해 영어 번역이 논의되었고 제임스 1세에 이르러 그의 번역을 기초로 한 킹제임스 버전 흠정역 성경이 나오게 되었다.

토머스 모어에 대한 비판[편집]

윌리엄 틴데일은 가톨릭 교회에서 성인으로 추앙받고 있는 토머스 모어를 “예수를 배신한 유다”라며 신랄하게 비판했다. 그는 1531년에 토머스 모어가 쓴 《이단에 관한 대화》를 반박하는 글 《토머스 경의 대화에 대한 응답》을 썼다. 이 책의 여백에다 그는 토머스 모어를 ‘거짓의 교황!’이라고 명시해 놓았다. 틴데일은 토머스 모어가 전통을 성경보다 더 높게 평가한다고 생각했기 때문이었다. 틴데일은 이 책에서 고백성사, 순례, 사죄경, 연옥, 십자가 기둥에 기도하기 등 가톨릭 전례들을 모두 바보스러운 의식과 성사라고 비판했다. 이러한 가톨릭을 옹호하는 모어를 “예수를 배신한 유다”라고 비판했다. 그는 모어가 복음의 진리를 외면하는 이유를 “성직자의 관을 쓴 자들의 도움으로 명예와 높은 자리, 권력과 돈을 얻기 위한 것”이라고 야유했다.

이에 토머스 모어는 분노했고 1532년에 장장 6권으로 된 책 《틴데일의 응답을 논박함》을 펴냈다.이에 끝나지 않고 그는 틴데일과 그 추종자들을 색출해 화형에 처하는데 앞장섰다. 토머스 모어는 틴데일을 교회법으로나 세속법으로 옭아매어 빠져 나갈 수 없게 만들고 틴데일의 추종자였던 ‘작은 빌니’, 틴데일의 책을 영국으로 반입했던 베이필드, 런던의 가죽 상인 존 튜크스베리를 화형시켰다. 그리고 틴데일의 영어성경과 저작들을 가지고 있던 법률가 제임스 베인햄을 잡아 모진 고문과 심문을 가했다. 하지만 그는 모진 고문 앞에서도 틴데일은 나쁜 사람이 아니라고 진술했다. 그는 모진 고문과 협박에도 신념을 철회하지 않았다. 그는 화형대에서도 모국어 성경을 갖는 것은 정당하며, 로마의 주교는 적그리스도이며, 연옥은 존재하지 않으며, 그리스도의 피로 정결하게 되는 것이라고 주장했다. 게다가 하나님께 토머스 모어를 용서하라고 기도까지 하며 화형대에서 처형 당했다.[3]

체포와 처형[편집]

틴데일은 엔트베르펜에서 숨어 살았다. 그는 엔트베르펜에 오기 전 함부르크에서 1529년에 모세 5경을 번역했다. 엔트베르펜에 1년간 숨어 지내다가 영국인 밀고자의 고발로 황제의 대리인에게 붙잡히고 만다. 그는 황제의 법령에 의해 1536년 10월초에 사형을 선고 받았다. “주여, 영국 왕의 눈을 뜨게 하소서!” 라는 마지막 말을 남기고 화형당했다.

일화[편집]

에라스무스의 친구인 윌리엄 버치우스의 말에 따르면 틴데일은 영어를 비롯해 히브리어, 헬라어, 라틴어, 이탈리아어, 에스파냐어, 프랑스어의 7개국어를 할 줄 알며 "그가 어떤 언어라도 모국어처럼 말하는 것을 본다면 매우 놀랄 것이다." 라고 말했다.

동시대의 인물[편집]

- 피에트로 폼포나치 : 이탈리아의 철학자로 이타주의적인 삶을 강조하였다. 이런 르네상스적 가르침은 영국 청교도들의 혐오의 대상이었다.[4]

- 데시데리위스 에라스뮈스: 옥스포드 대학 출신의 당시 가장 영향력있는 학자였다.

- 토마스 빌니 : 영국의 종교개혁의 아버지라고 불리는 최초의 순교자이다. 틴데일에게도 영향을 주었다.[5]

각주[편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다. |

- ↑ Knappen, M. M. (Marshall Mason), 1901-1966. (1970, ©1966). 《Tudor Puritanism : a chapter in the history of idealism》. University of Chicago Press. 4쪽.

- ↑ 오덕교《종교개혁사》(합동신학대학원출판부,P384)

- ↑ “성서, 영어 번역하고 화형당한 영국의 루터 윌리엄 틴데일 (下)” (국민일보). 2012년 1월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Knappen, M. M. (Marshall Mason), 1901-1966. (1970, ©1966). 《Tudor Puritanism : a chapter in the history of idealism》. University of Chicago Press. 5쪽.

- ↑ “영국 종교개혁의 아버지 토마스 빌니”. 2019년 1월 30일. 2020년 1월 18일에 확인함.

ウィリアム・ティンダル

ウィリアム・ティンダル(William Tyndale [ˈtɪndəl], 1494年あるいは1495年 - 1536年10月6日)は、イギリスの宗教改革家で聖書をギリシャ語・ヘブライ語原典から初めて英語に翻訳した人物。はじめはヘンリ8世の好意を得たが、王の結婚に反対して信任を失った。また宗教改革への弾圧によりヨーロッパを逃亡しながら聖書翻訳を続けるも、1536年逮捕され、現在のベルギーで焚刑に処された。その後出版された欽定訳聖書は、ティンダル訳聖書に大きく影響されており、それよりもむしろさらに優れた翻訳であると言われる。実際、新約聖書の欽定訳は、8割ほどがティンダル訳のままとされる。

すでにジョン・ウィクリフによって、最初の英語訳聖書が約100年前に出版されていたが、ティンダルはそれをさらに大きく押し進める形で、聖書の書簡の多くの書を英訳した。

文献[編集]

- デイヴィド・ダニエル(田川建三訳)『ウィリアム・ティンダル ある聖書翻訳者の生涯』勁草書房、2001年1月、ISBN 4326101326

- David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography, Yale University Press, 30 Nov 1994, ISBN 0300061323 / Paperback: 1st Mar 2001, ISBN 0300068808

関連項目[編集]

外部リンク[編集]

- William Tyndale's Translation(英語)- Wesley Center Online(アーカイブ )

- The Tyndale Society(英語)- ティンダル・ソサエティー

- WilliamTyndale.com(英語)- Friends of William Tyndale(アーカイブ)

- Tyndale(英語)- Bible-Researcher.com

- William Tyndale quotes(英語)- ThinkExist.com(アーカイブ)

- Works by William Tyndale(英語)- プロジェクト・グーテンベルク

田川訳の伝記に関するもの[編集]

William Tyndale

William Tyndale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1494 |

| Died | c. (aged 42) |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Magdalen Hall, Oxford University of Cambridge |

| Known for | Tyndale Bible |

William Tyndale (/ˈtɪndəl/;[1] sometimes spelled Tynsdale, Tindall, Tindill, Tyndall; c. 1494 – c. 6 October 1536) was an English scholar who became a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation in the years leading up to his execution. He is well known as a translator of the Bible into English, influenced by the works of Erasmus of Rotterdam and Martin Luther.[2]

A number of partial English translations had been made from the 7th century onwards, but the religious ferment caused by Wycliffe's Bible in the late 14th century led to the death penalty for anyone found in unlicensed possession of Scripture in English, though translations were available in all other major European languages.[3]

Tyndale worked during a Renaissance of scholarship, which saw the publication of Reuchlin's Hebrew grammar in 1506. Greek was available to the European scholarly community for the first time in centuries, as it welcomed Greek-speaking intellectuals and texts following the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Notably, Erasmus compiled, edited, and published the Greek Scriptures in 1516. Luther's German Bible appeared in 1522.

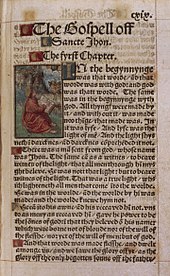

Tyndale's translation was the first English Bible to draw directly from Hebrew and Greek texts, the first English translation to take advantage of the printing press, the first of the new English Bibles of the Reformation, and the first English translation to use Jehovah ("Iehouah") as God's name as preferred by English Protestant Reformers.[a] It was taken to be a direct challenge to the hegemony of both the Catholic Church and the laws of England maintaining the church's position.

A copy of Tyndale's The Obedience of a Christian Man (1528), which some claim or interpret to argue that the king of a country should be the head of that country's church rather than the Pope, fell into the hands of the English King Henry VIII, providing a rationalisation for breaking the Church in England from the Catholic Church in 1534.[4][5] In 1530, Tyndale wrote The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry's annulment of his own marriage on the grounds that it contravened Scripture.[6] Fleeing England, Tyndale sought refuge in the Flemish territory of the Catholic Emperor Charles V. In 1535, Tyndale was arrested and jailed in the castle of Vilvoorde (Filford) outside Brussels for over a year. In 1536, he was convicted of heresy and executed by strangulation, after which his body was burnt at the stake. His dying prayer was that the King of England's eyes would be opened; this seemed to find its fulfilment just one year later with Henry's authorisation of the Matthew Bible, which was largely Tyndale's own work, with missing sections translated by John Rogers and Miles Coverdale.

Tyndale's translation of the Bible was used for subsequent English translations, including the Great Bible and the Bishops' Bible, authorised by the Church of England. In 1611 after seven years of work, the 47 scholars who produced the King James Bible[7] drew significantly from Tyndale's original work and the other translations that descended from his.[8] One estimate suggests that the New Testament in the King James Version is 83% Tyndale's words and the Old Testament 76%.[9][10] Hence, the work of Tyndale continued to play a key role in spreading Reformation ideas across the English-speaking world and eventually across the British Empire. In 2002, Tyndale was placed 26th in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[11][12]

Life[edit]

Tyndale was born around 1494[b] in Melksham Court, Stinchcombe, a village near Dursley, Gloucestershire.[13] The Tyndale family also went by the name Hychyns (Hitchins), and it was as William Hychyns that Tyndale was enrolled at Magdalen Hall, Oxford. Tyndale's family had moved to Gloucestershire at some point in the 15th century, probably as a result of the Wars of the Roses. The family originated from Northumberland via East Anglia. Tyndale's brother Edward was receiver to the lands of Lord Berkeley, as attested to in a letter by Bishop Stokesley of London.[14]

Tyndale is recorded in two genealogies[15][16] as having been the brother of Sir William Tyndale of Deane, Northumberland, and Hockwold, Norfolk, who was knighted at the marriage of Arthur, Prince of Wales to Catherine of Aragon. Tyndale's family was thus descended from Baron Adam de Tyndale, a tenant-in-chief of Henry I. William Tyndale's niece Margaret Tyndale was married to Protestant martyr Rowland Taylor, burnt during the Marian Persecutions.

At Oxford[edit]

Tyndale began a Bachelor of Arts degree at Magdalen Hall (later Hertford College) of Oxford University in 1506 and received his B.A. in 1512, the same year becoming a subdeacon. He was made Master of Arts in July 1515 and was held to be a man of virtuous disposition, leading an unblemished life.[17][incomplete short citation] The M.A. allowed him to start studying theology, but the official course did not include the systematic study of Scripture. As Tyndale later complained:

He was a gifted linguist and became fluent over the years in French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, and Spanish, in addition to English.[18] Between 1517 and 1521, he went to the University of Cambridge. Erasmus had been the leading teacher of Greek there from August 1511 to January 1512, but not during Tyndale's time at the university.[19]

Tyndale became chaplain at the home of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury in Gloucestershire and tutor to his children around 1521. His opinions proved controversial to fellow clergymen, and the next year he was summoned before John Bell, the Chancellor of the Diocese of Worcester, although no formal charges were laid at the time.[20][incomplete short citation] After the meeting with Bell and other church leaders, Tyndale, according to John Foxe, had an argument with a "learned but blasphemous clergyman", who allegedly asserted: "We had better be without God's laws than the Pope's.", to which Tyndale responded: "I defy the Pope, and all his laws; and if God spares my life, ere many years, I will cause the boy that driveth the plow to know more of the Scriptures than thou dost!"[21][22]

Tyndale left for London in 1523 to seek permission to translate the Bible into English. He requested help from Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, a well-known classicist who had praised Erasmus after working together with him on a Greek New Testament. The bishop, however, declined to extend his patronage, telling Tyndale that he had no room for him in his household.[23] Tyndale preached and studied "at his book" in London for some time, relying on the help of cloth merchant Humphrey Monmouth. During this time, he lectured widely, including at St Dunstan-in-the-West at Fleet Street in London.

In Europe

Tyndale left England for continental Europe, perhaps at Hamburg, in the spring of 1524, possibly travelling on to Wittenberg. There is an entry in the matriculation registers of the University of Wittenberg of the name "Guillelmus Daltici ex Anglia", and this has been taken to be a Latinisation of "William Tyndale from England".[24] He began translating the New Testament at this time, possibly in Wittenberg, completing it in 1525 with assistance from Observant Friar William Roy.

In 1525, publication of the work by Peter Quentell in Cologne was interrupted by the impact of anti-Lutheranism. A full edition of the New Testament was produced in 1526 by printer Peter Schöffer in Worms, a free imperial city then in the process of adopting Lutheranism.[25] More copies were soon printed in Antwerp. It was smuggled from continental Europe into England and Scotland. The translation was condemned in October 1526 by Bishop Tunstall, who issued warnings to booksellers and had copies burned in public.[26] Marius notes that the "spectacle of the scriptures being put to the torch... provoked controversy even amongst the faithful."[26] Cardinal Wolsey condemned Tyndale as a heretic, first stated in open court in January 1529.[27][incomplete short citation]

From an entry in George Spalatin's diary for 11 August 1526, Tyndale apparently remained at Worms for about a year. It is not clear exactly when he moved to Antwerp. The colophon to Tyndale's translation of Genesis and the title pages of several pamphlets from this time purported to have been printed by Hans Lufft at Marburg, but this is a false address. Lufft, the printer of Luther's books, never had a printing press at Marburg.[28]

Following the hostile reception of his work by Tunstall, Wolsey and Thomas More in England, Tyndale retreated into hiding in Hamburg and continued working. He revised his New Testament and began translating the Old Testament and writing various treatises.[29]

Opposition to Henry VIII's annulment[edit]

In 1530, he wrote The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry VIII's planned annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon in favour of Anne Boleyn, on the grounds that it was unscriptural and that it was a plot by Cardinal Wolsey to get Henry entangled in the papal courts of Pope Clement VII.[30][31] The king's wrath was aimed at Tyndale. Henry asked Emperor Charles V to have the writer apprehended and returned to England under the terms of the Treaty of Cambrai; however, the emperor responded that formal evidence was required before extradition.[32] Tyndale developed his case in An Answer unto Sir Thomas More's Dialogue.[33]

Betrayal and death[edit]

Eventually, Tyndale was betrayed by Henry Phillips[34] to authorities representing the Holy Roman Empire.[35] He was seized in Antwerp in 1535, and held in the castle of Vilvoorde (Filford) near Brussels.[36] Some suspect that Phillips was hired by Bishop Stokesley to gain Tyndale's confidence and then betray him.

He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and was found guilty and condemned to be burned to death, despite Thomas Cromwell's intercession on his behalf. Tyndale "was strangled to death while tied at the stake, and then his dead body was burned".[37] His final words, spoken "at the stake with a fervent zeal, and a loud voice", were reported as "Lord! Open the King of England's eyes."[38][39] The traditional date of commemoration is 6 October, but records of Tyndale's imprisonment suggest that the actual date of his execution might have been some weeks earlier.[40] Foxe gives 6 October as the date of commemoration (left-hand date column), but gives no date of death (right-hand date column).[36] Biographer David Daniell states the date of death only as "one of the first days of October 1536".[39]

Within four years, four English translations of the Bible were published in England at the king's behest,[c] including Henry's official Great Bible. All were based on Tyndale's work.[41]

Theological views[edit]

Tyndale seems to have come out of the Lollard tradition, which was strong in Gloucestershire. Tyndale denounced the practice of prayer to saints.[42] He also rejected the then orthodox church view that the Scriptures could only be interpreted by approved clergy.[43] While his views were influenced by Luther, Tyndale also deliberately distanced himself from the German reformer on several key theological points, including transubstantiation, which Tyndale rejected.[44]

Printed works[edit]

Although best known for his translation of the Bible, Tyndale was also an active writer and translator. As well as his focus on the ways in which religion should be lived, he had a focus on political issues.

| Year Printed | Name of Work | Place of Publication | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1525 | The New Testament Translation (incomplete) | Cologne | |

| 1526* | The New Testament Translation (first full printed edition in English) | Worms | |

| 1526 | A compendious introduction, prologue or preface into the epistle of Paul to the Romans | ||

| 1527 | The parable of the wicked mammon | Antwerp | |

| 1528 | The Obedience of a Christen Man[45] (and how Christen rulers ought to govern...) | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1530* | The five books of Moses [the Pentateuch] Translation (each book with individual title page) | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1530 | The practice of prelates | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1531 | The exposition of the first epistle of saint John with a prologue before it | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1531? | The prophet Jonah Translation | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1531 | An answer into Sir Thomas More's dialogue | ||

| 1533? | An exposicion upon the. v. vi. vii. chapters of Mathew | ||

| 1533 | Erasmus: Enchiridion militis Christiani Translation | ||

| 1533 | The Souper of the Lorde | Nornburg | Niclas Twonson |

| 1534 | The New Testament Translation (thoroughly revised, with a second foreword against George Joye's unauthorised changes in an edition of Tyndale's New Testament published earlier in the same year) | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1535 | The testament of master Wylliam Tracie esquire, expounded both by W. Tindall and J. Frith | ||

| 1536? | A path way into the holy scripture | ||

| 1537 | The Matthew Bible, which is a Holy Scripture Translation (Tyndale, Rogers, and Coverdale) | Hamburg | Richard Grafton |

| 1548? | A brief declaration of the sacraments | ||

| 1573 | The whole works of W. Tyndall, John Frith, and Doct. Barnes, edited by John Foxe | ||

| 1848* | Doctrinal Treatises and Introductions to Different Portions of the Holy Scriptures, edited by Henry Walter.[46] | Tindal, Frith, Barnes | |

| 1849* | Expositions and Notes on Sundry Portions of the Holy Scriptures Together with the Practice of Prelates, edited by Henry Walter.[46] | ||

| 1850* | An Answer to Sir Thomas More's Dialogue, The Supper of the Lord after the True Meaning of John VI. and I Cor. XI., and William Tracy's Testament Expounded, edited by Henry Walter.[46] | ||

| 1964* | The Work of William Tyndale | ||

| 1989** | Tyndale's New Testament | ||

| 1992** | Tyndale's Old Testament | ||

| Forthcoming | The Independent Works of William Tyndale | ||

| Forthcoming | Tyndale's Bible - The Matthew Bible: Modern Spelling Edition | ||

*These works were printed more than once, usually signifying a revision or reprint. However the 1525 edition was printed as an incomplete quarto and was then reprinted in 1526 as a complete octavo. **These works were reprints of Tyndale's earlier translations revised for modern spelling. | |||

Legacy[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Lutheranism |

|---|

|

Impact on the English language[edit]

In translating the Bible, Tyndale introduced new words into the English language; many were subsequently used in the King James Bible, such as Passover (as the name for the Jewish holiday, Pesach or Pesah) and scapegoat. Coinage of the word atonement (a concatenation of the words 'At One' to describe Christ's work of restoring a good relationship—a reconciliation—between God and people)[47] is also sometimes ascribed to Tyndale.[48][49] However, the word was probably in use by at least 1513, before Tyndale's translation.[50][51] Similarly, sometimes Tyndale is said to have coined the term mercy seat.[52] While it is true that Tyndale introduced the word into English, mercy seat is more accurately a translation of Luther's German Gnadenstuhl.[53]

As well as individual words, Tyndale also coined such familiar phrases as:

- my brother's keeper

- knock and it shall be opened unto you

- a moment in time

- fashion not yourselves to the world

- seek and ye shall find

- ask and it shall be given you

- judge not that ye be not judged

- the word of God which liveth and lasteth forever

- let there be light

- the powers that be

- the salt of the earth

- a law unto themselves

- it came to pass

- the signs of the times

- filthy lucre

- the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak (which is like Luther's translation of Matthew 26,41: der Geist ist willig, aber das Fleisch ist schwach; Wycliffe for example translated it with: for the spirit is ready, but the flesh is sick.)

- live, move and have our being

Controversy over new words and phrases[edit]

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church did not approve of some of the words and phrases introduced by Tyndale, such as "overseer", where it would have been understood as "bishop", "elder" for "priest", and "love" rather than "charity". Tyndale, citing Erasmus, contended that the Greek New Testament did not support the traditional readings. More controversially, Tyndale translated the Greek ekklesia (Greek: εκκλησία), (literally "called out ones"[54][55]) as "congregation" rather than "church".[56][incomplete short citation] It has been asserted this translation choice "was a direct threat to the Church's ancient – but so Tyndale here made clear, non-scriptural – claim to be the body of Christ on earth. To change these words was to strip the Church hierarchy of its pretensions to be Christ's terrestrial representative, and to award this honour to individual worshipers who made up each congregation."[56][incomplete short citation][55]

Tyndale was accused of errors in translation. Thomas More commented that searching for errors in the Tyndale Bible was similar to searching for water in the sea and charged Tyndale's translation of The Obedience of a Christian Man with having about a thousand false translations. Bishop Tunstall of London declared that there were upwards of 2,000 errors in Tyndale's Bible, having already in 1523 denied Tyndale the permission required under the Constitutions of Oxford (1409), which were still in force, to translate the Bible into English. In response to allegations of inaccuracies in his translation in the New Testament, Tyndale in the Prologue to his 1525 translation wrote that he never intentionally altered or misrepresented any of the Bible but that he had sought to "interpret the sense of the scripture and the meaning of the spirit."[56][incomplete short citation]

While translating, Tyndale followed Erasmus's 1522 Greek edition of the New Testament. In his preface to his 1534 New Testament ("WT unto the Reader"), he not only goes into some detail about the Greek tenses but also points out that there is often a Hebrew idiom underlying the Greek.[57] The Tyndale Society adduces much further evidence to show that his translations were made directly from the original Hebrew and Greek sources he had at his disposal. For example, the Prolegomena in Mombert's William Tyndale's Five Books of Moses show that Tyndale's Pentateuch is a translation of the Hebrew original. His translation also drew on the Latin Vulgate and Luther's 1521 September Testament.[56][incomplete short citation]

Of the first (1526) edition of Tyndale's New Testament, only three copies survive. The only complete copy is part of the Bible Collection of Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart. The copy of the British Library is almost complete, lacking only the title page and list of contents. Another rarity is Tyndale's Pentateuch, of which only nine remain.

Impact on English Bibles[edit]

The translators of the Revised Standard Version in the 1940s noted that Tyndale's translation, including the 1537 Matthew Bible, inspired the translations that followed: The Great Bible of 1539; the Geneva Bible of 1560; the Bishops' Bible of 1568; the Douay-Rheims Bible of 1582–1609; and the King James Version of 1611, of which the RSV translators noted: "It [the KJV] kept felicitous phrases and apt expressions, from whatever source, which had stood the test of public usage. It owed most, especially in the New Testament, to Tyndale".

Brian Moynahan writes: "A complete analysis of the Authorised Version, known down the generations as 'the AV' or 'the King James', was made in 1998. It shows that Tyndale's words account for 84% of the New Testament and for 75.8% of the Old Testament books that he translated."[58][incomplete short citation] Joan Bridgman makes the comment in the Contemporary Review that, "He [Tyndale] is the mainly unrecognised translator of the most influential book in the world. Although the Authorised King James Version is ostensibly the production of a learned committee of churchmen, it is mostly cribbed from Tyndale with some reworking of his translation."[59]

Many of the English versions since then have drawn inspiration from Tyndale, such as the Revised Standard Version, the New American Standard Bible, and the English Standard Version. Even the paraphrases like the Living Bible have been inspired by the same desire to make the Bible understandable to Tyndale's proverbial ploughboy.[60][22]

George Steiner in his book on translation After Babel refers to "the influence of the genius of Tyndale, the greatest of English Bible translators."[61] He has also appeared as a character in two plays dealing with the King James Bible, Howard Brenton's Anne Boleyn (2010) and David Edgar's Written on the Heart (2011).

Memorials[edit]

A memorial to Tyndale stands in Vilvoorde, Flanders, where he was executed. It was erected in 1913 by Friends of the Trinitarian Bible Society of London and the Belgian Bible Society.[62] There is also a small William Tyndale Museum in the town, attached to the Protestant church.[63] A bronze statue by Sir Joseph Boehm commemorating the life and work of Tyndale was erected in Victoria Embankment Gardens on the Thames Embankment, London, in 1884. It shows his right hand on an open Bible, which is itself resting on an early printing press. A life-sized bronze statue of a seated William Tyndale at work on his translation by Lawrence Holofcener (2000) was placed in the Millennium Square, Bristol, United Kingdom.

The Tyndale Monument was built in 1866 on a hill above his supposed birthplace, North Nibley, Gloucestershire. A stained-glass window commemorating Tyndale was made in 1911 for the British and Foreign Bible Society by James Powell and Sons. In 1994, after the Society had moved their offices from London to Swindon, the window was reinstalled in the chapel of Hertford College in Oxford. Tyndale was at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, which became Hertford College in 1874. The window depicts a full-length portrait of Tyndale, a cameo of a printing shop in action, some words of Tyndale, the opening words of Genesis in Hebrew, the opening words of John's Gospel in Greek, and the names of other pioneering Bible translators. The portrait is based on the oil painting that hangs in the college's dining hall. A stained glass window by Arnold Robinson in Tyndale Baptist Church, Bristol, also commemorates the life of Tyndale.

Several colleges, schools and study centres have been named in his honour, including Tyndale House (Cambridge), Tyndale University (Toronto), the Tyndale-Carey Graduate School affiliated to the Bible College of New Zealand, William Tyndale College (Farmington Hills, Michigan), and Tyndale Theological Seminary (Shreveport, Louisiana, and Fort Worth, Texas), the independent Tyndale Theological Seminary[64] in Badhoevedorp, near Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Tyndale Christian School in South Australia and Tyndale Park Christian School[65] in New Zealand. An American Christian publishing house, also called Tyndale House, was named after Tyndale.

There is an Anglican communion setting in memoriam William Tyndale, The Tyndale Service, by David Mitchell.

Liturgical commemoration[edit]

By tradition Tyndale's death is commemorated on 6 October.[13] There are commemorations on this date in the church calendars of members of the Anglican Communion, initially as one of the "days of optional devotion" in the American Book of Common Prayer (1979),[66] and a "black-letter day" in the Church of England's Alternative Service Book.[67] The Common Worship that came into use in the Church of England in 2000 provides a collect proper to 6 October (Lesser Festival),[68] beginning with the words:

Tyndale is honoured in the Calendar of saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America as a translator and martyr the same day.

Films about Tyndale[edit]

- The first biographical film about Tyndale, titled William Tindale, was released in 1937.[69][70]

- The second, titled God's Outlaw: The Story of William Tyndale, was released in 1986.

- A cartoon film about his life, titled Torchlighters: The William Tyndale Story, was released ca. 2005.[71]

- The film Stephen's Test of Faith (1998) includes a long scene with Tyndale, how he translated the Bible and how he was put to death.[72]

- The documentary film, William Tyndale: Man with a Mission, was released ca. 2005. The movie included an interview with David Daniell.[citation needed]

- Another known documentary is the film William Tyndale: His Life, His Legacy.[73]

- The 2-hour Channel 4 documentary, The Bible Revolution, presented by Rod Liddle, details the roles of historically significant English Reformers John Wycliffe, William Tyndale, and Thomas Cranmer.

- The "Battle for the Bible" (2007) episode of the PBS Secrets of the Dead series, narrated by Liev Schreiber, features Tyndale's story and legacy and includes historical context. This film is an abbreviated and revised version of the PBS/Channel 4 version, and replaces some British footage with that more relevant to American audiences.[citation needed]

- In 2011, BYUtv produced a miniseries on the creation of the King James Bible that focused heavily on Tyndale's life called Fires of Faith.[74][75]

- 2013, The Most Dangerous Man in Tudor England, BBC Two, 60-minute documentary written and presented by Melvyn Bragg[76]

Tyndale's pronunciation[edit]

Tyndale was writing at the beginning of the Early Modern English period. His pronunciation must have differed in its phonology from that of Shakespeare at the end of the period. In 2013 linguist David Crystal made a transcription and a sound recording of Tyndale's translation of the whole of Saint Matthew's Gospel in what he believes to be the pronunciation of the day, using the term "original pronunciation". The recording has been published by The British Library on two compact discs with an introductory essay by Crystal.[77]

See also[edit]

- Tyndale Bible

- Luther Bible

- Matthew Bible

- Textus Receptus

- Works of Arnold Wathen Robinson, reference to stained glass featuring William Tyndale

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ In the seventh paragraph of Introduction to the Old Testament of the New English Bible, Sir Godfry Driver wrote, "The early translators generally substituted 'Lord' for [YHWH]. [...] The Reformers preferred Jehovah, which first appeared as Iehouah in 1530 A.D., in Tyndale's translation of the Pentateuch (Exodus 6.3), from which it passed into other Protestant Bibles."

- ^ Tyndale's birth was about 1494 according to History of the Revised Version in 1881.

- ^ Miles Coverdale's, Thomas Matthew's, Richard Taverner's, and the Great Bible.

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Tyndale". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Partridge 1973, pp. 38–39, 52–52.

- ^ Marshall 2017, p. 117.

- ^ Daniell & Noah 2004.

- ^ Daniell 1994, p. [page needed].

- ^ Bourgoin 1998, p. 373.

- ^ King James Bible Preface

- ^ Harding 2012.

- ^ Tadmor 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Nielson & Skousen 1998.

- ^ Parrill & Robison 2013, p. 93.

- ^ "William Tyndale", Historical Figures, BBC, retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ a b Daniell 2011.

- ^ Demaus 1886, p. 21.

- ^ John Nichol, "Tindal genealogy", Literary Anecdotes, 9.

- ^ "Tyndale of Haling", Burke's Landed Gentry (19th century ed.)

- ^ Moynahan 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Daniell 1994, p. 18.

- ^ Daniell 2001, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Moynahan 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Wansbrough 2017, p. 126, Ch.7 Tyndale.

- ^ a b Foxe 1926, Ch. XII.

- ^ Tyndale, William (1530), "Preface", Five bokes of Moses.

- ^ Samworth 2010.

- ^ Cochlaeus 1549, p. 134.

- ^ a b Ackroyd 1999, p. 270.

- ^ Moynahan 2003, p. 177.

- ^ "Antwerpen, Hamburg, Antwerpen", Tyndale (biography) (in German).

- ^ Stapleton 1983, p. 905.

- ^ Bourgoin 1998.

- ^ Marius 1999, p. 388:"...English kings on one side and the wicked popes and English bishops on the other. Cardinal Wolsey embodies the culmination of centuries of conspiracy, and Tyndale's hatred of Wolsey is so nearly boundless that it seems pathological."

- ^ Bellamy 1979, p. 89:"Henry claimed that Tyndale was spreading sedition, but the Emperor expressed his doubts and argued that he must examine the case and discover proof of the English King's assertion before delivering the wanted man."

- ^ Tyndale 1850.

- ^ Edwards 1987.

- ^ "Tyndale", Bible researcher

- ^ a b Foxe 1570, p. VIII.1228.

- ^ Farris 2007, p. 37.

- ^ Foxe 1570, p. VIII. 1229.

- ^ a b Daniell 2001, p. 383.

- ^ Arblaster, Paul (2002). "An Error of Dates?". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ Hamlin & Jones 2010, p. 336.

- ^ McGoldrick 1979.

- ^

Quotations related to William Tyndale at Wikiquote

Quotations related to William Tyndale at Wikiquote - ^ "Where Did Tyndale Get His Theology?". Christian History Institute.

- ^ Tyndale, William, The Obedience of a Christian Man.

- ^ a b c Cooper 1899, p. 247.

- ^ Andreasen, Niels-erik A (1990), "Atonement/Expiation in the Old Testament", in Mills, WE (ed.), Dictionary of the Bible, Mercer University Press.

- ^ McGrath 2000, p. 357.

- ^ Gillon 1991, p. 42.

- ^ "atonement", OED,

1513 MORE Rich. III Wks. 41 Having more regarde to their olde variaunce then their newe attonement. [...] 1513 MORE Edw. V Wks. 40 of which… none of vs hath any thing the lesse nede, for the late made attonemente.

- ^ Harper, Douglas, "atone", Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Shaheen 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Moo 1996, p. 232, note 62.

- ^ "Rev 22:17", Believer's Study Bible (electronic ed.), Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997,

the word ... ekklesia ... is a compound word coming from the word kaleo, meaning 'to call,' and ek, meaning 'out of'. Thus... 'the called-out ones'. Eph 5:23, "This is the same word used by the Greeks for their assembly of citizens who were 'called out' to transact the business of the city. The word ... implies ... 'assembly'.

- ^ a b Harding 2012, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d Moynahan 2003, p. 72.

- ^ Tyndale, William. "Tyndale's New Testament (Young.152)". Cambridge Digital Library. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Moynahan 2003, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Bridgman 2000, pp. 342–346.

- ^ Anon (n.d.), The Bible in the Renaissance – William Tyndale, Oxford, archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- ^ Steiner 1998, p. 366.

- ^ Le Chrétien Belge, 18 October 1913; 15 November 1913.

- ^ Museum.

- ^ Tyndale Theological Seminary, EU.

- ^ Tyndale park, NZ: School.

- ^ Hatchett 1981, p. 43, 76–77.

- ^ Draper 1982.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ William Tindale (1937) at IMDb

- ^ "William Tindale - (1937)".

- ^ "The William Tyndale Story". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Stephen's Test of Faith (1998) at IMDb

- ^ William Tyndale: His Life, His Legacy (DVD). ASIN B000J3YOBO.

- ^ Toone 2011.

- ^ Fires of Faith: The Coming Forth of the King James Bible, BYU Television

- ^ Melvyn Bragg. "The Most Dangerous Man in Tudor England". BBC Two.

- ^ Tyndale, William (2013), Crystal, David (ed.), Bible, St Matthew's Gospel, read in the original pronunciation, The British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-5127-0, NSACD 112-113.

Sources[edit]

- Ackroyd, Peter (1999). The Life of Thomas More. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-7493-8640-5.

- Arblaster, Paul; Juhász, Gergely; Latré, Guido, eds. (2002), Tyndale's Testament, Brepols, ISBN 2-503-51411-1

- Bellamy, John G. (1979). The Tudor Law of Treason: An Introduction. London: Routledge & K. Paul. ISBN 978-0-8020-2266-0.

- Bourgoin, Suzanne Michele (1998). Encyclopedia of World Biography: Studi-Visser. Vol 15. Gale Research. ISBN 978-0-7876-2555-9.

- Bridgman, Joan (2000), "Tyndale's New Testament", Contemporary Review, 277 (1619): 342–46

- Cahill, Elizabeth Kirkl (1997), "A bible for the plowboy", Commonweal, 124 (7).

- Cochlaeus, Joannes (1549), Commentaria de Actis et Scriptis Martini Lutheri[Commentary on Acts and Martin Luther’s writings] (in Latin), St Victor, near Mainz: Franciscus Berthem

- Cooper, Thompson (1899), , in Lee, Sidney (ed.), Dictionary of National Biography, 59, London: Smith, Elder & Co, pp. 246–247

- Daniell, David (1994), William Tyndale: A Biography, New Haven, CT & London: Yale University Press.

- Daniell, David (2001) [1994], William Tyndale: A Biography, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p. 382–383, ISBN 978-0-300-06880-1.

- Daniell, David (19 May 2011). "Tyndale, William (c.1494–1536)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27947. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.), The first edition of this text is available at Wikisource: . Dictionary of National Biography. 57. 1899.

- Daniell, David (interviewee); Noah, William H. (producer/researcher/host) (c. 2004), William Tyndale: his life, his legacy (videorecording), Avalon

- Demaus, Robert (1886). William Tyndale, a Biography: A Contribution to the Early History of the English Bible. London: Religious Tract Society. p. 21.

- Day, John T (1993), "Sixteenth-Century British Nondramatic Writers", Dictionary of Literary Biography, 1, pp. 296–311

- Draper, Martin, ed. (1982). The Cloud of Witnesses: A Companion to the Lesser Festivals and Holydays of the Alternative Service Book, 1980. London: The Alcuin Club.

- Edwards, Brian H. (1987). "Tyndale's Betrayal and Death". Christianity Today(16). Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Farris, Michael (2007). From Tyndale to Madison: How the Death of an English Martyr Led to the American Bill of Rights. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8054-2611-3.

- Foxe, John (1570), "Acts and Monuments", Book of Martyrs Variorum, HRI[permanent dead link].

- Foxe, John (1926) [1563]. "Ch. XII". In Forbush, William Byron (ed.). The Book of Martyrs. New York: Holt, Rinehart And Winston.[permanent dead link]

- Gillon, Campbell (1991). Words to Trust. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-389-20949-2.

- Hamlin, Hannibal; Jones, Norman W. (2010), The King James Bible After Four Hundred Years: Literary, Linguistic, and Cultural Influences, Cambridge University Press, p. 336, ISBN 978-0-521-76827-6

- Harding, Nathan (2012). Christ: Lost in the word (Paperback ed.). Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-304-65816-6.[self-published source?]

- Hatchett, Marion J. (1981). Commentary on the American Prayer Book. Seabury Press. ISBN 978-0-8164-0206-9.

- Marius, Richard (1999). Thomas More: A Biography. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-88525-7.

- Marshall, Peter (2017). Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300170627.

- McGoldrick, James Edward (1979). Luther's English connection: the Reformation thought of Robert Barnes and William Tyndale. Northwestern Pub. House. ISBN 978-0-8100-0070-4.

- McGrath, Alister E. (2000). Christian Literature: An Anthology. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-21606-3.

- Moo, Douglas J. (1996). The Epistle to the Romans. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2317-5.

- Moynahan, Brian (2003a), God's Bestseller: William Tyndale, Thomas More, and the Writing of the English Bible—A Story of Martyrdom and Betrayal, St. Martin's Press

- Moynahan, Brian (2003b), William Tyndale: If God Spare my Life, London: Abacus, ISBN 0-349-11532-X

- Nielson, Jon; Skousen, Royal (1998). "How Much of the King James Bible Is William Tyndale's?". Reformation. 3 (1): 49–74. doi:10.1179/ref_1998_3_1_004. ISSN 1357-4175.

- Parrill, Sue; Robison, William B. (2013). The Tudors on Film and Television. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-0031-4.

- Partridge, Astley Cooper (1973). English Biblical translation. London: Deutsch. ISBN 9780233961293.

- Piper, John, Why William Tyndale Lived and Died, Desiring God Ministries, archived from the original on 8 July 2011, retrieved 1 November 2008.

- Reidhead, Julia, ed. (2006), The Norton Anthology: English Literature (8th ed.), New York, NY, p. 621

- Samworth, Herbert (27 February 2010), "The Life of William Tyndale : Part 5 - Tyndale in GErmany", Tyndale's Ploughboy, retrieved 7 October 2020

- Shaheen, Naseeb (2011). Biblical References in Shakespeare's Plays. University of Delaware. ISBN 978-1-61149-373-3.

- Stapleton, Michael, ed. (1983), The Cambridge Guide to English Literature, London: Cambridge University Press

- Steiner, George (1998). After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-288093-2.

- Tadmor, Naomi (2010), The Social Universe of the English Bible: Scripture, Society, and Culture in Early Modern England, Cambridge UP, p. 16, ISBN 978-0-521-76971-6

- Toone, Trent (15 October 2011), "BYUtv tells story of the King James Bible in 'Fires of Faith'", Deseret News

- Tyndale, William (2000), O'Donnell, Anne M, SND; Wicks, Jared SJ (eds.), An Answer Unto Sir Thomas Mores Dialoge, Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, ISBN 0-8132-0820-3.

- Tyndale, William (1850). An answer to Sir Thomas More's Dialogue, The supper of the Lord, after the true meaning of John VI. and 1 Cor. XI., and Wm. Tracy's Testament expounded. Cambridge: University Press.

- Tyndale, William (2000) [Worms, 1526], The New Testament (original spelling reprint ed.), The British Library, ISBN 0-7123-4664-3.

- Tyndale, William (1989) [Antwerp, 1534], The New Testament (modern English spelling, complete with Prologues to the books and marginal notes, with the original Greek paragraphs reprint ed.), Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-04419-4

- Wansbrough, Henry (2017). "Tyndale". In Richard Griffiths (ed.). The Bible in the Renaissance: Essays on Biblical Commentary and Translation in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-89404-3.

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Mombert, JI (1914). "Tyndale, William". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge(third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Mombert, JI (1914). "Tyndale, William". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge(third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

Further reading[edit]

- Hooker, Morna (19 October 2000). "Tyndale as Translator". The Tyndale Society. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "William Tyndale: A hero for the information age", The Economist, pp. 101–3, 20 December 2008. The online version corrects the name of Tyndale's Antwerp landlord as "Thomas Pointz" vice the "Henry Pointz" indicated in the print ed.

- Teems, David (2012), Tyndale: The Man Who Gave God An English Voice, Thomas Nelson

- Werrell, Ralph S. (2006), The Theology of William Tyndale, Dr. Rowan Williams, foreword, James Clarke & Co, ISBN 0-227-67985-7

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Tyndale. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: William Tyndale |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Tyndale, William". |

- William Tyndale at Find a Grave

- "Tyndale", Secrets of the Dead (Documentary), PBS.

- Tyndale, William, Translation (cleartext), Source forge, archived from the original on 22 May 2013, retrieved 25 October 2011

- Family search.

- Portraits of William Tyndale at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- The Tyndale Society.

- Works by William Tyndale at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Tyndale at Internet Archive

- Works by William Tyndale at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- William Tyndale's Bible

- https://tyndalebible.com/[1]