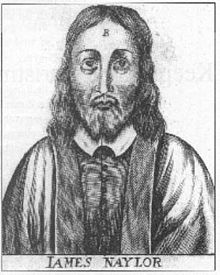

James Nayler

James Nayler (or Naylor; 1618–1660) was an English Quaker leader. He was among the members of the Valiant Sixty, a group of early Quaker preachers and missionaries. In 1656, Nayler achieved national notoriety when he re-enacted Christ's Palm Sunday entry into Jerusalem by entering Bristol on a horse. He was imprisoned and charged with blasphemy.[1]

Early life[edit]

Nayler was born in the town of Ardsley in Yorkshire. In 1642 he joined the Parliamentarian army, and served as quartermaster under John Lambert until 1650.[citation needed]

Religious experience[edit]

After experiencing what he took to be the voice of God calling him from work in his fields, Nayler gave up his possessions and began seeking a spiritual direction, which he found in Quakerism after meeting the leader of the movement, George Fox, in 1652. Nayler became the most prominent of the travelling Quaker evangelists known as the Valiant Sixty. He drew many converts and was considered a skilled theological debater.

Rift with Fox[edit]

Fox's concerns over the acts of Nayler's followers[edit]

Beginning in 1656, Fox expressed concerns to Nayler that both Nayler's ministry and that of his associate Martha Simmonds were becoming over-enthusiastic and erratic. Fox's concerns apparently centred specifically on Nayler allowing a group of his followers to see in Nayler himself in some sense a great prophet or even a messiah figure.[2] On 21 and 22 September 1656,[3][4] Fox visited Nayler twice in prison at Exeter and admonished him. Over the visits, Nayler continued to reject Fox's words. Prominent Quaker author Rufus M. Jones provides a description of the strained encounter:

Bristol Palm Sunday Re-enactment and sentencing for blasphemy[edit]

In October 1656, Nayler and his friends, including Simmonds, staged a demonstration that proved disastrous: Nayler re-enacted the Palm Sunday arrival of Christ in Jerusalem.

Following Nayler's Palm Sunday Re-enactment, Nayler and some of his followers were apprehended and subsequently examined before Parliament. It was found that many of Nayler's followers had referred to him by such titles as "Lord", "Prince of Peace", etc., apparently believing that Nayler was in some manner representing the return of Jesus Christ.[6] On 16 December 1656 he was convicted of blasphemy in a highly publicised trial before the Second Protectorate Parliament. Narrowly escaping execution, he was sentenced to be put in the pillory and on there to have a red-hot iron bored through his tongue, and also to be branded with the letter B for Blasphemer on his forehead, and other public humiliations.[7] Subsequently he was imprisoned for two years of hard labour.[8]

The Nayler case was part of a broader political attack against the Quakers. Initially, it was discussed under the Blasphemy Ordinance of 1648 with the hope of imposing an authoritative Presbyterian religious settlement on the Commonwealth – the Presbyterians had also attempted to use the Ordinance against John Biddle in the previous parliament. Ultimately the prosecution did not rely on any statute. Many of the speeches in the debates about Nayler centred on Biblical tradition on heresy (including calling for the death penalty) and generally urged MPs to quash vice and heresy. After the verdict, Cromwell rejected representations on behalf of Nayler, but at the same time wanted to make sure the case did not provide a precedent for action against the people of God.[9]

To modern eyes, Nayler's Palm Sunday Re-enactment might not seem particularly outrageous, especially when compared with other acts of some of the other early Quaker activists, who would occasionally disrupt church services, or sometimes go out disrobed in public, being "naked as a sign", and as a supposed symbol of spiritual innocence. At the time, Quakers were already being pressed to denounce the doctrine of the Inner Light for its implication of equality with Christ, and Nayler's ambiguous symbolism was seen as playing with fire. The Society's subsequent move, mostly driven by Fox, toward a somewhat more organised structure, with Meetings given the ability to disavow a member, seemed to have been moved by a desire to avoid similar problems.

Aftermath[edit]

George Fox was horrified by the Bristol event, recounting in his Journal that "James ran out into imaginations, and a company with him; and they raised up a great darkness in the nation," despite Nayler's belief that his actions were consistent with Quaker theology, and despite Fox's own having occasionally acted in certain ways as if he himself might have been somehow similar to the Biblical prophets. Yet Fox and the movement in general denounced Nayler publicly, though this did not stop anti-Quakers from using the incident to paint Quakers as heretics or equate them with Ranters.

Reconciliation with Fox[edit]

Nayler left prison in 1659 a physically ruined man. He soon went to pay a visit to George Fox, before whom he then knelt and asked for forgiveness, repenting of his earlier actions. Afterwards he was formally, if still reluctantly, forgiven by Fox.

Final year, writings and death[edit]

Having been accepted again by Fox, Nayler joined other Quaker critics of the Cromwellian regime, condemning the nation's rulers. In October 1660, while travelling to rejoin his family in Yorkshire, he was robbed and left near death in a field, then brought to the home of a Quaker doctor in Kings Ripton, Huntingdonshire. A day later and two hours before he died on 21 October, aged 42, he made a moving statement which many Quakers since have come to value:[10]

James Nayler was buried on 21 October 1660 in Thomas Parnell's burial ground at Kings Ripton.[11] According to the village website, "There is also a Quaker's Burial ground to the rear of 'Quakers Rest' on Ramsey Road."[12]

Publications[edit]

- The Works of James Nayler, by Quaker Heritage Press, a complete edition of Nayler's works including letters previously available in manuscripts. The editor modernizing the spelling, punctuation, etc. noting significant textual variants without changing the original wording . The set is available in book form or in an unabridged on-line edition.[13][14] (2009).

- There Is A Spirit: The Nayler Sonnets is a collection, first published in 1945, of 26 poems by Kenneth Boulding, each inspired by a four- to sixteen-word portion of Nayler's dying statement (and also includes the intact statement). Boulding gave permission for the publication of his The Nayler Sonnets to Irene Pickard who printed them in 1944 in the periodical she was editing from New York City, "Inward Light". The "There is a spirit ..." statement forms section 19.12 of Britain Yearly Meeting's anthology Quaker Faith and Practice. The Swarthmore Lecture has the title Ground and Spring, taken from Nayler's "There is a spirit ..." statement. (2007).

- The Sorrows of the Quaker Jesus: James Nayler and the Puritan Crackdown on the Free Spirit.[15] (1996).

- Refutation of some of the more Modern Misrepresentations of the Society of Friends commonly called Quakers, with a Life of James Nayler, by Joseph Gurney Bevan. (1800).

- Memoir of the Life, Ministry, Trial, and Sufferings of James Nayler. (1719).

- Tracts of Nayler entitled A Collection of Sundry Books, Epistles, and Papers Written by James Nayler, Some of Which Were Never Before Printed: with an Impartial Relation of the Most Remarkable Transactions Relating to His Life (1716) edited by his friend (and important early Quaker) George Whitehead, though Whitehead omitted Nayler's more controversial works and freely edited and changed the text. Note that this volume appeared after the death of George Fox, who opposed the re-issuing of ANY of Nayler's writings. Fox, however, did appropriate and issue with only cosmetic changes as "Epistle 47" a 1653 letter written by Nayler as his own in the 1698 edition of Fox's epistles.[16]

- A Relation of the Life, Conversion, Examination, Confession, and Sentence of James Nayler. (1657).

See also[edit]

- Leo Damrosch, The Sorrows of the Quaker Jesus; ISBN 0-674-82143-2

Notes[edit]

- ^ Nicolas Walter, Blasphemy: Ancient and Modern. London: Rationalist Press Association, 1990.

- ^ Sewel, William (1834). The History of the Rise, Increase and Progress of the Quakers. Intermixed Wih Several Remarkable Occurrences, Written Originally in Low Dutch, and Also Translated by Hymself Into English. The 6. Ed. Darton. p. 181.

- ^ Fox, George. The journal of George Fox. p. 268-269.

- ^ Fox, George (1903). George Fox: An Autobiography. Ferris & Leach. p. 271.

- ^ Jones, Rufus (1919). The Story Of George Fox. New York Macmillan. p. 83.

- ^ Cobbett's Complete Collection of State Trials... p. 836. By Thomas Bayly Howell. 1810. Publisher: R. Bagshaw. Downloaded 1 Oct. 2017.

- ^ John Henry Barrow (1840), The Mirror of Parliament, 2, Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans., p. 1070, has the complete sentence from Parliament; see also the legend in the picture to the right.

- ^ William G. Bittle, James Nayler 1618–1660: The Quaker Indicted by Parliament, York: Sessions of York, 1996, pp. 131–145.

- ^ Blair Worden (2012) God's Instruments: Political Conduct in the England of Oliver Cromwell. OUP. pp. 81–85. ISBN 9780199570492

- ^ a b "19.12 | Quaker faith & practice". qfp.quaker.org.uk. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Braithwaite's Beginnings of Quakerism (1911), p. 275.

- ^ About Kings Ripton.

- ^ The Works of James Nayler, qhpress.org; accessed 12 November 2014.

- ^ Licia Kuenning, ed. The Works of James Nayler (1618–1660). 4 vols. Farmington, ME: Quaker Heritage Press, 2003–2009.

- ^ The Sorrows of the Quaker Jesus: James Nayler and the Puritan Crackdown on the Free Spirit, By Leo Damrosch. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996, pp. 6, 238.

- ^ The Works of James Nayler. Volume I (Farmington, ME: Quaker Heritage Press, 2003) p. 317, n. 1.

References[edit]

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nayler, James". Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 318.

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has the text of the 1885–1900 Dictionary of National Biography's article about Nayler, James. |

| Wikisource has the text of A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature's article about Nayler, James. |

- The Complete Works of James Nayler in four volumes, Quaker Heritage Press on-line edition; accessed 12 November 2014.

- A Collection of Sundry Books, Epistles, and Papers Written by James Nayler, Some of Which Were Never Before Printed: with an Impartial Relation of the Most Remarkable Transactions Relating to His Life (1716), Internet Archive with downloadable pdfs of this copy of the George Whitehead edition.

- James Nayler's Spiritual Writings 1653–1660, strecorsoc.org; accessed 12 November 2014.

- Naylor's Failure, hallvworthington.com; accessed 12 November 2014.

- James Nayler's "There is a spirit ..." statement, strecorsoc.org; accessed 12 November 2014.

- Stuart Masters, Why Do We Blame the Victim? In Defence of James Nayler (March 2012), aquakerstew.blogspot.co.uk; accessed 12 November 2014.

- "Passages detailing James Nayler's ride into Bristol from Bristol Past And Present" by James Fawckner Nicholls and John Taylor (published 1882); accessed 12 November 2014.

- The Genealogy of James Nayler at WikiTree

- 1618 births

- 1660 deaths

- Protestant missionaries in England

- Protestant mystics

- Former Anglicans

- Converts to Quakerism

- Deaths by beating in Europe

- English Caroline nonconforming clergy

- English Protestant missionaries

- English Christian theologians

- English criminals

- English Dissenters

- English letter writers

- English Quakers

- English religious writers

- English theologians

- Founders of religions

- Government opposition to new religious movements

- History of Quakerism

- Interregnum (England)

- Lay theologians

- Military personnel of the English Civil War

- Nonconformism

- People convicted of blasphemy

- People from the Metropolitan Borough of Barnsley

- People of the English Civil War

- People of the Interregnum (England)

- Quaker ministers

- Quaker theologians

- Quaker writers

- Quakerism in London

- Roundheads

- Trials in London

- 17th-century English clergy

- 17th-century English writers

- 17th-century English male writers