14. PERENNIAL PHILOSOPHY

You have mentioned the subject of perennial philosophy in some of your books, often critically but sometimes more appreciatively. What is the reason for this?

That vexed subject entails the investigation of an extensive corpus of materials unknown to the popular circuit of interest in such matters. This corpus involves many complexities totally neglected by “new spirituality,” a vulgar contemporary distraction devised by profiteers. Those materials are known to the world of scholarship, even though interpretations are often fragmented or provisional.

Because I became acquainted with a quantity of these materials in my unofficial research project, I attempted to make known something of the range involved in Minds and Sociocultures (1995), of sufficient length to deter casual readers. The history of religion and philosophy is not a subject that readily appeals to the retail bookshops dealing in flotsam like occultism, alternative therapy, and spiritualism. Many people have a taste for deceptive offerings, and so they are fed those by the commercial process. They are very prone to commercial books that are easily readable, reassuring them about what they have formerly been told, which may be completely erroneous.

14.1

The Traditionalists: Guenon, Schuon, and Coomaraswamy

14.2

The Aldous Huxley Backslide

14.3

Divergences and Alternatives

14.4

The Constructivist Counter

14.5

Ken Wilber and Adi Da Samraj

14.6

Rude Boy Andrew Cohen

14.7

The Findhorn Foundation Contrivance

14.8

Ken Wilber Integralism and the Critical Reaction

14.9

The Wild West Blog Showdown

14.10

Neoperennialism in Question

14.1 The Traditionalists: Guenon, Schuon, and Coomaraswamy

The history of religion and philosophy is a very big subject. Contractions are common. How much history is there in popular "perennial philosophy"? In this respect, my own views and conclusions do not converge with those of well known writers like Frithjof Schuon or Ken Wilber. Briefly, Schuon represents the “traditionalist” model of “religio perennis,” while Wilber represents the neoperennial “integral” approach. These two exponents are generally considered to be at opposite ends of the spectrum of exegesis. Their followers tend to insinuate that these interpreters have more or less expressed the last word on the subject. However, disagreements are possible. Wilber’s version has been contested by some of his former supporters.

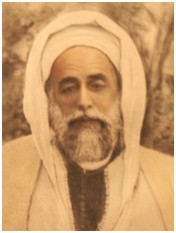

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) is another well known exponent, nearer to Schuon than to Wilber, although some differences in output are clearly discernible. A critical version of Coomaraswamy may be found in one of my early works (The Resurrection of Philosophy, pp. 234-244). I could doubtless improve upon that now (the book was written in 1984-5), but the approach suffices as evidence of some basic disagreements. I sympathise with the complaints of Coomaraswamy about the superiority complex of Western nations. However, as compensation he did enjoy a privileged position at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts for three decades until his death. Of mixed race, his father was Ceylonese and his mother English. He was a very erudite art historian who wrote many learned articles that are still of significance (see Roger Lipsey, ed., Coomaraswamy, 3 vols, 1977). Some assessors have been disconcerted by the influence upon Coomaraswamy of the Neo-Scholastic movement associated with Aquinas. Theological colouring has provided a bone of contention.

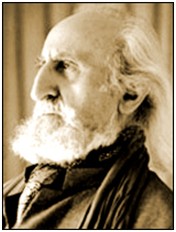

l to r: Rene Guenon, Frithjof Schuon, Shaikh Ahmad al-Alawi

There is no doubt that Frithjof Schuon and Rene Guenon (1886-1951) created interest in Sufism, a subject serving to counterbalance the predominant Western popular focus upon occultism and Theosophy. Guenon was the originator of that trend. This French Roman Catholic converted to Islam and Sufism during 1911-12 in Paris. He was not insularist, believing that other religions were derivatives of a universal truth, though having suffered distortions. He started to write books in the 1920s. Guenon expressed strong criticisms of Western society. In 1930 he settled in Cairo, his second wife being an Egyptian Muslim. He lived in Egypt for the rest of his life as a Muslim Sufi with the name of Abdul Wahid Yahya.

The 1920s output of Guenon influenced the German Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998), who corresponded with Guenon for many years until they met in Egypt during 1938. Schuon had earlier visited Algeria in 1932 and there encountered Shaikh Ahmad al-Alawi (1869-1934), a Sufi figurehead representing the Shadhili dervish tradition. Alawi showed an unusual respect for Christians; he had travelled to France in 1926. Alawi preferred to reconcile Islam and modernity, even favouring the controversial practise of translating the Quran into French. One of Schuon’s followers later contributed an academic work on the Algerian. See Martin Lings, A Sufi Saint of the Twentieth Century: Shaikh Ahmad al-Alawi (1961; new edn,1993).

Schuon later spent much time in America, where he demonstrated an empathy for the Plains Indians, being adopted by Sioux and Crow families. Probably his most well known book is The Transcendent Unity of Religions (1953). His influential follower Martin Lings (d.2005) subsequently contributed a biography of the prophet of Islam which gained acclaim in the Muslim world. See Lings, Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources (1983).

Along with Schuon and Guenon, Coomaraswamy is regarded as one of the three founders of perennialism or the “Traditionalist School.” Yet his writings are very different from those of Guenon, exhibiting more scholarship. Guenon neglected Buddhism, while Coomaraswamy integrated this factor. Guenon dwelt primarily upon Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism. He was critical of Buddhism as a Hindu heresy, having been misled by some Hindus he had encountered. This drawback worried some of his acquaintances, including Schuon and Marco Pallis. Not until 1946 did Guenon acknowledge the error. Pallis emphasised that there were many pages in the books of Guenon needing revision accordingly (Martin Lings, "Rene Guenon," Sophia Vol. 1 no. 1, 1995).

Guenon disowned being a philosopher, tending to support the caste dogmas of Hinduism, a gesture viewed by some commentators as a serious flaw in his exegesis. Whereas Coomaraswamy moved at a tangent in his attempt to demonstrate the unity of Vedanta and Platonism. That was a difficult assignment, attended by some popular beliefs about Plato and the Greek Neoplatonists which have no secure basis.

l to r: Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Aldous Huxley

14.2 The Aldous Huxley Backslide

By far the most well known work in the genre under discussion was Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy (1945). Huxley (1894-1963) was a controversial British novelist celebrated in America. He became a resident of California in the late 1930s. His book on perennialism was influenced by Coomaraswamy and others, being well known for such definitions of the subject as: “the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality” (The Perennial Philosophy, p.vii). A decade later, Huxley settled for the psychedelic imitation of lofty themes he had promoted. He resorted to mescaline in 1953, and took his first dose of LSD in 1955. Huxley retained the psychedelic habit until his death.

Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception (1954) advocated mescaline usage. That book exerted a damaging influence, being favoured by the 1960s psychedelic wave; some commentators have described that work as one of the major texts used by the American drug enthusiasts like Timothy Leary. The retrograde influence of Huxley was facilitated by his lectures in the early 1960s at the Esalen Institute of California, a venue that became a seedbed for the Human Potential Movement (Shepherd, Minds and Sociocultures Vol. One, 1995, pp. 148ff). Ever since that period, the “perennial philosophy” has been a toy of the psychedelic mentality. Some LSD enthusiasts have distinguished their pursuit from the “contemplative” route, even deeming the latter to be inferior. The differences are very obvious. Another distraction was that numerous clients attended new age “workshops,” creating further sensations and delusions such as “self-realisation.”

14.3 Divergences and Alternatives

In a very different sector, critics reacted to the emerging Schuonite insistence that a spiritual path is inseparable from a revealed religion. Schuon was believed to represent Sufism, Vedanta, and Platonism. However, the Greek philosophical tradition is not associated with a revealed religion, despite some Neoplatonist tendencies of Proclus. The subject of perennialism has to be carefully probed. The unity of religions is an attractive theme. There is surely nothing wrong when this approach leads to an intercultural empathy with American Indians, Muslims, and Hindus. The vexations relate to a wider scheme of definitions, in contraction of which the Guenonian neglect of Buddhism is one example. Another point of disagreement is that Schuon strongly criticised Swami Vivekananda (d.1902) from the standpoint of an inflexible authoritarianism (Shepherd, The Resurrection of Philosophy, 1989, pp. 247ff.). Ironically, Vivekananda was strongly associated with sanatana dharma, the “eternal religion” of Hinduism esteemed by Schuon.

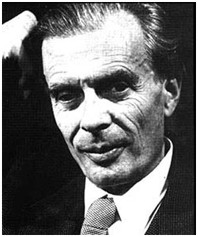

l to r: Hazrat Babajan, Sai Baba of Shirdi

In another camp, some Western partisans of Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta tend to suggest that religions like Islam are inferior to the “non-dual” variety. Dogmatism is a problem in the new age also, with “non-dualism” becoming one of the new commercial lures for the uncritical. Some of the most fascinating figures I have encountered in diverse materials were Muslims, if unorthodox in their orientation. Two of my early works commemorated Hazrat Babajan (d.1931) of Poona (Pune) and Hazrat Sai Baba of Shirdi (d.1918). Babajan (a Pathan faqir) is reputed to have been buried alive by religious zealots (though she escaped). Shirdi Sai Baba has frequently been presented as a Hindu in devotional sources. See my Hazrat Babajan: A Pathan Sufi of Poona (2014); Sai Baba of Shirdi: A Biographical Investigation (2015); Sai Baba: Faqir of Shirdi (2017).

See also Shirdi Sai Baba for an overview of the Muslim identity. Many details are missing from the preferred partisan version of this figure associated with B. V. Narasimhaswami. A relevant disciple of Shirdi Sai was Upasani Maharaj (d.1941), a Hindu whose profile has formerly been neglected. I have contributed a four part online biography of some length.

Critics of “perennial philosophy” argue the obvious factor that various doctrines mentioned by Coomaraswamy and others are basically different. I have pointed this out myself more than once, to the point of being unpopular with those who conflate Buddhist doctrine with Hinduism. Myopic readers have sometimes assumed that, in referring to a perennial philosophy, I must be saying the same thing as Schuon or Wilber. Even my early chapter nine in The Resurrection of Philosophy is proof to the contrary, the title of that chapter specifying perennial folly. The treatment of religious traditions, in the sequel Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals (2004), is antithetic to the fluent consumerist scenario in which readily familiar mottos prevail over complexities.

For more analysis, see Early Sufism in Iran and Central Asia. See also Al-Hakim al-Tirmidhi and Egyptian Sufi Dhu'l Nun al-Misri. The ninth century Nubian Dhu'l Nun was an early Sufi living in the Coptic town of Akhmim; "he was probably black-skinned." See also Hallaj, a well known mystical entity in a far less well known social and political context. The complex Zoroastrian heritage is often overlooked. Mongolian and Tibetan history is frequently missing from popular Western versions of "shamanism." The phase of early Christian monasticism in Egypt remains a mystery to fashionable contemporary preferences.

14.4 The Constructivist Counter

The “contextualist” or constructivist critique of simplistic perennial philosophy came from Steven T. Katz in Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis (1978). Professor Katz, a scholar and philosopher, converged with poststructuralist doctrines in depicting mystical experiences as being intimately related to cultural characteristics, language styles, and personalities. He was concerned to contest Huxley, opposing the psychedelic movement. In his argument, there can be no pure experiences because of the cultural acclimatisations involved. Katz was in opposition to Joseph Campbell, Aldous Huxley, and Huston Smith. So is the present writer, though from a different perspective. Cf. Huston Smith, Cleansing the Doors of Perception (2000), describing the author’s introduction to mescaline in 1961 by the manic Timothy Leary. Linguistic and cultural conditioning arguments are relevant, but not exhaustive, in relation to the elusive experiential context for which substitutes are so frequently improvised.

In more general directions, the poststructuralist trend has relegated science to an indigent quarter of the academic edifice via such postmodernists as Paul Feyerabend, whose aesthetic inclinations to Dadaism are a testimony to caprice. Some commentators in this category say there is nothing outside the linguistic text. Like Derrida, their approach can be considered more nihilistic than empirical. Many “postmodernists” consider truth to be unattainable, a pessimism that is not enviable.

Professor Katz perceived that American Buddhism and American Hinduism did not resemble the originals, his point being that Westerners were influenced by their cultural conditioning into accepting a lax version of Asiatic religion (John Horgan, Rational Mysticism, 2003, p.46). However, this does not mean, for instance, that Gautama Buddha never had any “transcendent” experiences, only that the psychedelic new age wave were frequently incapable of such an elementary Asiatic observance as celibacy. Katz did not actually deny mystical experiences; he argued that there is no way of proving these are true even if they are true. In which case they could be true, so the subject is far from being closed by constructivism or poststructuralism. It is not necessary to believe that meditation is the key. Meditation has comprised a means of deception in suspect circles.

14.5 Ken Wilber and Adi Da Samraj

There is yet another basic problem discernible. Some exponents of the perennial insist that they are able to chart advanced experiential states of mind. The difficulties arising here are related to evident factors of subjective preference. For instance, in Ken Wilber’s version of the perennial, a controversial American guru, early known as Da Free John, was credited with very advanced experiential states. This elevation was strongly disputed elsewhere in view of the antinomian reputation of Da Free John, alias Adi Da Samraj (Shepherd, Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals, pp. 74-101). The related surfeit of “crazy wisdom” lore has percolated the American scene in popular alternative religion, with confusions abounding as a consequence.

l to r: Ken Wilber, Adi Da Samraj

The real name of Da Free John was Franklin Jones (1939-2008). This entity generated an extreme form of pseudo-perennialism (some critics say that he was only equalled in that respect by Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh). He exhibited a changing preference for exotic names, both for himself and his sect. Over the years he styled himself as Bubba Free John, Heart Master Da, Avatar Adi, Da Avadhoota, Da Love Ananda, Da Kalki, Da Avabhasa, and Adi Da Samraj. At the time of his death, his full title was Ruchira Avatar Adi Da Samraj. His community became known as Adidam, formerly favouring such designations as Free Daism and the Johannine Daist Communion.

There are strong overtones of Hindu language in these flamboyant representations, which illustrate Adi Da’s erratic tangent from his contact with the controversial guru Swami Muktananda (d.1982), the founder of Siddha Yoga. Adi Da became the disciple of this guru in 1968, subsequently claiming that he had gained full enlightenment in 1970. A rather suspicious detail is that Adi Da was a member of Scientology during the interim.

Adi Da Samraj claimed the highest spiritual honours, in terms of being an Avatar, strongly implied as the peak achievement of perennial wisdom. He is one of the doubtful roles in Western neo-Advaita presuming to have inherited the legacy of Ramana Maharshi. His books are celebrated by some American enthusiasts of “non-dualism,” while also arousing criticism. Adi Da tabulated various religions and mystics in a way that evidently suited his preferences, his own professed creed of non-dualism being at the top of the list. He is inseparable from the subject of “crazy wisdom,” a disability shared with the bohemian Tantric Buddhist known as Chogyam Trungpa (1939-1987), who has the repute of being an alcoholic.

Various devotees of Adi Da became disaffected, some of them filing lawsuits. Reports emerged that wild parties continued in his immediate environment during the 1970s and early 80s; he encouraged his devotees to watch pornographic movies. He was said to have nine “wives,” and to exercise a habit of drawing other women devotees into intimate sexual contact. The recipients of such amorous attention were frequently wives and girlfriends of male devotees; however, Avatar Adi Da resorted to the explanation that he was thereby assisting male devotees to overcome their sexual attachments. He himself was, of course, beyond all attachments as a supreme spiritual authority who must not be doubted.

An island in Fiji became a refuge for Adi Da after the lawsuits filed against him in the mid-1980s. One lawsuit (filed by Beverly O’Mahoney) accused him of fraud, intentional infliction of emotional distress, brainwashing, and sexual abuse. This list of charges is not exhaustive. The accuser here stated that she had been forced, via alcohol consumption, into sexual orgies during her seven years as a devotee of Adi Da in California and on the elite Fijian island. The media described her as a sex slave. That description does not seem an undue exaggeration in view of some details afforded. The relevant report was "Sex Slave Sues Guru: Pacific Isle Orgies Charged," San Francisco Chronicle, 04/04/1985. The Daist community resorted to elaborate justifications and evasions in a manner increasingly recognised as being the hallmark of cults. The legal claims were settled out of court.

The Mahoney lawsuit alleged that the non-profit tax-exempt status of the Johannine Daist Communion was a sham designed for the personal advantage of Adi Da. An Australian devotee is known to have contributed two million dollars to buy the Fijian island in 1983. By the time of the lawsuits in the mid-1980s, a cult counselling centre in Berkeley had assisted about fifty disillusioned ex-devotees of Adi Da. These people were no longer in the mood for exotic claims and titles.

The San Francisco Chronicle, in April 1985, reported the harrowing experience of a woman devotee who had bad memories of sexual abuse as a child. The remedy of the abnormally lustful Adi Da was to make her have oral sex with three other devotees, after which he himself indulged in sexual relations with the victim. She was hysterical as a consequence; she later related that this traumatic episode took years for her to come to terms with. This report has since appeared in chapter 20 of Geoffrey D. Falk, Stripping the Gurus (online).

A literate ex-devotee was the Indologist Georg Feuerstein (d.2012), who made significant criticisms of Adi Da in one section of a popular “crazy wisdom” book (Holy Madness, second edition, 2006). That book is known for some disconcerting confusions. However, Dr. Feuerstein emphasised that partisan accounts of Adi Da were glossed and mythologised, especially the autobiographical materials. For instance, Adi Da’s membership of Scientology for about a year in 1968-9 was a detail later relegated. That detail did not suit the hagiology of enlightenment inherited from Hindu Yoga.

The assessments of Ken Wilber are also problematic. This admirer of Adi Da penned influential encomiums. Wilber’s version of perennial philosophy proved very popular in America; the influence of Adi Da is clearly discernible. In 1996, Wilber posted a warning against the activities of this American guru, observing that the hideout in Fiji represented an extremist position, one which had effectively curtailed Adi Da’s influence on the mainland. Disconcertingly, Wilber still expressed praise for the books of Adi Da, which had evidently influenced him deeply. See Wilber, The Case of Adi Da. Wilber was here still implying a form of spiritual development in the antinomian entity who had retreated to Fiji.

In 1998, Wilber confirmed his ambiguous view of Adi Da Samraj, stating: “He is one of the greatest spiritual Realisers of all time, in my opinion, and yet other aspects of his personality lag far behind those extraordinary heights” (widely quoted online). The journalist John Horgan described his interview with Wilber in 2000, commenting: “Although he (Wilber) now sees Da Free John as a deeply flawed individual, Wilber still thinks the guru is a brilliant mystical philosopher” (Horgan, Rational Mysticism, 2003, p. 70). In contrast, I believe that the discrepancy proves the absence of any spiritual achievement. The word “realisation” is currently meaningless, at least in the sphere of “crazy wisdom” and “new spirituality.”

Ken Wilber wrote two open letters to the Daist community in 1998. One of these was briefly quoted in Wikipedia. The other letter was posted on a Shambhala website three years after composition. This communication clearly amounts to a support for Adi Da Samraj. Wilber here says that he neither regrets nor retracts his past endorsements of Adi Da; he was no longer able to give a public recommendation because of cultural and legal factors. Furthermore, he expresses satisfaction that his own writings had brought people to Adi Da. He still in fact recommended that “students who are ready” should become disciples of this guru. These major concessions annul Wilber’s apparent reservations in his more well known statement of 1996 abovementioned. This matter has been the subject of a negative verdict from Geoffrey D. Falk in chapter 20 of his online book Stripping the Gurus.

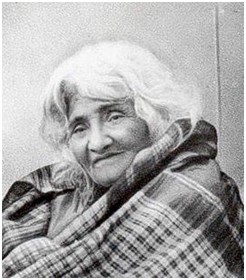

14.6 Rude Boy Andrew Cohen

The books of Ken Wilber frequently refer to enlightenment. Many readers have been disconcerted to find that Adi Da Samraj (or Franklin Jones) is credited by Wilber with a rare degree of enlightenment. The favoured word enlightenment here spells antinomian excesses. Ken Wilber’s underlying partisanship can arouse strong criticism. He has also elevated Andrew Cohen, another American guru closely related to the neo-Advaita trend. Wilber is well known for his dialogues with Cohen in the latter’s popular magazine What is Enlightenment? Cohen was there presented as the guru and Wilber as the pundit.

Ken Wilber wrote a glowing foreword for Cohen’s book Living Enlightenment (2002). Wilber here defended and extolled Cohen as a “Rude Boy,” the meaning being that of an enlightened teacher who confronts deficient attitudes. Wilber has also stated: “Every deeply enlightened teacher I have known has been a Rude Boy or Nasty Girl” (formerly cited in Wikipedia Ken Wilber, accessed 2008).

The crazy wisdom jargon is not to everyone’s taste. Wilber obviously believes that a number of enlightened teachers exist in America, which is surely reason to be wary of the attributes that may be encountered. Luna Tarlo, the mother of Andrew Cohen, denounced her son when he demonstrated the abuse of power and the psychology of obsession. The Rude Boy told a female devotee that her enlightenment was complete; however, when she expressed a concern to leave him, he accused her of being “a hypocrite, a liar, and a prostitute” (Tarlo, The Mother of God, 1997, pp. 83, 87). Casual use of the word enlightenment amounts to a mere figure of speech, an exercise in pseudo-significance. Tarlo also supplied an account in which Cohen implies that anyone who loves him is guaranteed enlightenment.

l to r: Ken Wilber, Andrew Cohen

There were defectors from the Cohen magazine What is Enlightenment? Despite praise of this magazine (known as WIE) by new age celebrities like Ken Wilber and Rupert Sheldrake, ex-devotees of Cohen are reported to have dismissed this media as “a hodge-podge of opinions that go nowhere.” The question posed was not being answered by the commercial magazine, according to dissenters and critics. This despite the prominence of Wilber in the glossy pages. See further chapter 21 of the online book Stripping the Gurus by Geoffrey D. Falk. The basis for the guru career of Andrew Cohen is that he spent two weeks with an obscure Advaita exponent in 1986, a man who promoted himself as an enlightened disciple of the long deceased Ramana Maharshi, who is currently a fantasy figure amongst Westerners. Two years later, Cohen founded EnlightenNext, a “nonprofit educational and spiritual network” which gained extensive promotion and funding.

An ex-devotee records how a wealthy subscriber gifted Cohen with two million dollars (over eighty per cent of her assets). The donor was subsequently reviled by the Rude Boy for being a narcissist who had not relinquished her ego (Andre Van der Braak, Enlightenment Blues: My Years with an American Guru, 2003, pp. 210-11). An ex-devotee website further attests Rude Boy drawbacks. Hal Blacker reports that three former editors of WIE had spoken out strongly against the Cohen abuses known amongst devotees. Cohen forced one of his students to “engage in daily visits to prostitutes in Amsterdam for weeks on end.” This ordeal was imposed as a retribution for past sexual indiscretions. Reference is also made to “the use of physical force and abuse against students.” There was “a kind of psychological torture chamber” at Foxhollow, the headquarters of EnlightenNext at Lenox, Massachusetts. See Hal Blacker, “A Farewell with Deep Gratitude” (April 2007) at the ex-devotee site What Enlightenment?

Jane O’Neil was the generous American who gifted Andrew Cohen with two million dollars to establish the Foxhollow h/q, assisting him to gain a semblance of legitimacy. Her subsequent routine, imposed by Cohen, involved a thousand daily prostrations to his picture. After five years as a devotee, in 1998 this subscriber fled under cover of darkness, not wishing to undergo the “humiliation, interrogation and virtual house arrest” which had been the fate of another defector. O'Neil was then blacklisted as a narcissist. See O’Neil, “Andrew Cohen and the Corruption of Power” (December 2006) at the same ex-devotee website.

Another relevant account is William Yenner, American Guru: A Story of Love, Betrayal and Healing - Former Students of Andrew Cohen Speak Out (2009). Yenner was a leading participant in Cohen's community for over a decade; his book has been considered significant. The Yenner website relayed that he "was left disillusioned and disappointed after a series of debilitating, abusive experiences." See also American Guru. For a review by Professor David C. Lane, see Andrew Cohen Exposed, expressing the verdict that Cohen "is in deep need of long term therapy."

The exposition of Ken Wilber is known as integralism, supposedly being all-comprehensive. The format has discernibly incorporated problems and obstacles instead of negotiating or eschewing these. The constant need for critical acumen has never been more imperative in the face of so many problems masquerading as enlightenment. It would be unwise to believe that a deficient integralism can achieve accuracy, in relation to past centuries, when the present is so confused in popular analysis. Solid data relating to history and texts is notably absent from the new age of Rude Boys.

14.7 The Findhorn Foundation Contrivance

In learned circles, various matters are debated about the history of religion, without always arriving at any clear resolution. In contrast, the popular field of “perennial philosophy” likes to simplify everything and present potted explanations of questionable value. Some very puzzling statements about this subject have appeared in readily saleable books. Even some scholars have taken liberties with materials, from the time of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy onwards. Many books eschew the history altogether, instead offering speculations without any solid reference points. Thus the history of religion becomes whatever the exponent wishes to believe. Opinions are more acceptable if there is sufficient context to justify such a recourse. The “perennial philosophy” is too often an unexamined concept, merely being regarded as having a saleable value.

Alex Walker

A very shallow claim to “perennial philosophy” occurred at the Findhorn Foundation in the 1990s. The claimant Alex Walker was an influential figure in this “new spirituality” organisation. “The perennial philosophy as the mystical centre of religious thought is the theory which you will work with while you live in this community” (Alex Walker, ed., The Kingdom Within, 1994, p. 36, cited in Shepherd, Minds and Sociocultures Vol. One, 1995, p. 923).

At that time I was living in Forres, almost next door to the Findhorn Foundation, and made a point of checking out this situation via close informants. The “theory” was so nebulous that it did not actually form part of the curriculum, which instead comprised new age “workshops” and alternative therapy, all sold for a high price. At this venue in 1993, official intervention had recommended suspension of Grof Transpersonal Training Inc., because of acute setbacks encountered by some clients, a matter causing alarm to Edinburgh University Pathology Department. Alex Walker was one of those who credited the claim of Stanislav Grof that Holotropic Breathwork had a pedigree in antique shamanism. Grof was in the habit of making glib references to “perennial philosophy,” causing further confusions.

There was no scholarship whatever in evidence at the Findhorn Foundation. Walker was an in-house financial consultant who advocated privatisation of community assets, on the lines of the contemporary capitalist model. His community suppressed and castigated dissidents while covering up an emerging debt which they vainly tried to offset by such means as privatisation. The inmates only knew of the “perennial philosophy” in a very derivative manner, mainly via the books of Ken Wilber, which were available in the community bookshop. Although Wilber cannot be blamed for the peculiarities of this “new spirituality” community during the 1990s and after, he did patronise the confusions by participating (via phone link) in a celebrity event with Andrew Cohen during 2009. See also Wilber in Dispute.

On the Findhorn Foundation, see Letter of Complaint to David Lorimer and Findhorn Foundation Discrepancies.

14.8 Ken Wilber Integralism and the Critical Reaction

The books of Ken Wilber have received enthusiastic elevation from his supporters. Critics do not rate the gestures in his early works towards alternative therapy and the Human Potential Movement. His Up from Eden (1981) gained partisan praise as a version of human evolution. Archaeology was in very scant evidence. The neo-Hegelian accents, and other features of Up from Eden theory, have aroused strong disagreement (see my Minds and Sociocultures Vol. One, 1995, pp. 101-127).

The vocabulary of Wilber identified with "integralism" by the time of his Integral Psychology (2000). That presentation was attended by the distinctive Wilberian terminology which has both attracted and repelled. Terms like the Great Nest of Being, the Kosmos, and the Integral Embrace are here in evidence; the dominating theory is that of Four Quadrants. Wilber tends to explain everything by such means and concepts, being inclined to assert the completeness of his theories. His numerous books gave him a monolithic status in alternative metaphysics. Although one may credit Ken Wilber’s industry in creating a worldview which attempts to explain so many factors, the “Everything” model does not convince his diverse critics.

Wilber’s promotion of Nagarjuna is known to be very problematic. He frequently refers to this early Indian Buddhist philosopher, using very limited source materials. “None of the relevant scholarship is mentioned in popular works like Ken Wilber’s neo-Hegelian treatise on evolution, which lends a ‘Dharmakaya’ sense of overwhelming priority to the Buddhist Madhyamaka philosopher Nagarjuna in relation to early Vedantic matters” (Shepherd, Minds and Sociocultures Vol. One, 1995, p. 664). Further, “Nagarjuna is often mentioned (by Wilber) with esteem, though with scant indication of the exegetical difficulties posed by that Buddhist exponent for specialist scholars” (Shepherd, Pointed Observations, 2005, pp. 51-2). I am not a specialist, so I will not attempt to be exhaustive on the point at issue (a few details can be found at 20.5 on this site).

The Wilber critic Jeff Meyerhoff has invoked poststructuralist thinking to evaluate Nagarjuna. He emphasises Wilber’s exegetical problem in relation to Nagarjuna’s association with nihilism and relativism. Meyerhoff also argues strongly against many other aspects of Wilber theory. See Meyerhoff, Bald Ambition: A Critique of Ken Wilber’s Theory of Everything (2010, also available as an online feature). A basic contention of the Meyerhoff critique is that Wilber generalises about subjects which are in basic debate amongst academic experts. Wilber incorporates those unresolved subjects into an ambitious metaphysical theory of Everything.

In relation to religion, neither Wilber nor Meyerhoff mention the provocative detail that Nagarjuna “according to some scholars was not a Mahayanist at all” (Shepherd, Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals, p. 98). Wilber tends very much to stress the supercession of Hinayana Buddhism by Mahayana, using an evolutionary argument in Up from Eden that was contested by the present writer many years ago. The counter-argument was ignored by American integralism, for whom Brits are virtually a martian race who expired in the Georgian era.

At the close of the 1990s, Ken Wilber founded the Integral Institute in Colorado. There have since been accusations of a cult-like approach from diverse critics, extending to associations with the founding member Andrew Cohen. See Geoffrey D. Falk, “Norman Einstein”: The Dis-Integration of Ken Wilber (2009). The Falk critique is lengthy, accusing Wilber of inaccuracy and narcissism. See also the more compact coverage in Michel Bauwens, The Cult of Ken Wilber. This contribution comes from a former fan of Wilber who subsequently complained of several tendencies perceived as serious flaws.

Wilber’s failure to negate his praise of Adi Da Samraj was a major hurdle for some of his admirers in the 1990s. Bauwens also describes the style of Wilber’s lengthy Sex, Ecology, Spirituality (1995) as being unduly aggressive in places. There is again the pervasive issue of matters taken for granted by Wilber that are actually more complex. Occurrences within the Integral Institute are indicated as fostering an exclusivist and depreciatory attitude on Wilber’s part to those outside his close circle. Furthermore, these dissatisfactions are aggravated by the claim of Wilber to “nondual realization” in his book One Taste (1999). His alliance with the meme theory of Don Beck and Chris Cowan is another issue. Wilber tended very much to relegate "green meme" ecological interests and other matters in preference for the elevation of presumably transpersonal roles allocated to higher memes. See Wilber, Integral Psychology (2000), chapter 4 (also article 13.18 on this website).

Frank Visser

A significant turnabout was demonstrated by Frank Visser, author of a detailed partisan guide to the life and work of the debated integralist (Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion, 2003). Visser is not American but Dutch, being located in Amsterdam. His subsequent commentaries provide a critical angle on Wilber, converging with the disillusionment of American partisans.

Visser is webmaster of the discussion site integralworld, formerly committed to promoting Wilber. Visser proved resistant to the new Wilber opus Integral Spirituality (2006). Visser observes: “It takes Wilber 178 pages to get to the topic of religion proper (in a book the main text of which is little over 200 pages).” Quote from Visser, Simply Too Much, October 16th 2006, at Wilber Watch. Visser described Wilber’s subsequent book The Integral Vision (2007) as “a rehash of material from Integral Spirituality” plus “a lot of flashy techno-erotic illustrations, and a couple of ‘1-minute exercises’ included in Integral Life Practice” (Wilber Assessment vs. Advertising, September 19th 2007).

14.9 The Wild West Blog Showdown

In June 2006, a key event in the Ken Wilber drama unfolded. The pundit of integral spirituality delivered a broadside on the web against his critics. See Wilber, What We Are, That We See Part 1: Response to Some Recent Criticism in a Wild West Fashion (June 8th, 2006). To be more specific, his former supporter Frank Visser was here the major target. Wilber’s memorable response to criticism was couched in a “Wild West” idiom explicitly associated with Wyatt Earp. This blog assault included vulgar phrases of questionable relevance. The main scenario here was Marshal Wilber’s intent to corner the outlaws and then ride on, “transcending and including more outlaws than any lawman dude type person in history.” Moreover, the transcender was “riding off into the sunset of integral peace and harmony.”

Wilber’s refrain was optimistic in view of critical reactions. Conclusions were expressed that he is averse to legitimate criticism, and was here demonstrating characteristics reminiscent of cult leaders. Cf. Frank Visser, The Wild West Wilber Report, including a bibliography of diverse critical responses to the provocative Wilber postings. Wilber's diction and claims can still sound extremist. To quote from his Wild West excess:

Wyatt has got to go back to work now, protecting the true and the good and the beautiful, while slaying partial-ass pervs, ripping their eyes out and pissing in their eye-sockets, using his Zen sword of prajna to cut off the heads of critics so staggeringly little that he has to slow down about 10-fold just to see them.... I am at the center of the vanguard of the greatest social transformation in the history of humankind.

14.10 Neoperennialism in Question

Ken Wilber failed to supply any detailed historical data in his books, relying upon a more abstract conceptualism. Critics reject the overstated theme of his work entitled A Brief History of Everything (1996). His “neoperennialism” is viewed as a premature substitute for the inadequately investigated antecedents.

Despite his promotion of Zen, Vajrayana Buddhism, and a transpersonalist version of Advaita Vedanta, Wilber has reflected biases of the American Human Potential Movement, nurtured at Esalen in the 1960s. For instance, five major traditions in the history of religion were stigmatised by Ken Wilber, in his longest work, with a marked degree of unsympathetic accusation. The crime alleged is ascetic repression. The traditions named are Gnosticism, Manichaeism, Theravada Buddhism, a type of Advaita Vedanta, and all forms of Christianity (Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, p. 520). Even Aristotle is added to the list of disdained parties.

This emphasis of Wilber does serve to illustrate the anomalies in contemporary preferences for “perennial philosophy.” This subject is charted elsewhere as denoting a predominantly contemplative complexion, frequently found in monastic and ascetic traditions. That disciplinary sector is unpopular in “new spirituality.” This American appetite passes muster as “integralism,” including a preference for the activities of suspect Rude Boys. A critical response to Wilber came from the pen of a British writer:

Many of the exemplars involved here were ascetics and disciplined contemplatives committed strongly to an other-worldly ideal not palatable to many modern Americans of the post-hippy era. The moderns under discussion are in no position to pass a judgment upon non-American spirituality in view of their own contrary tastes. Those moderns are a product of American capitalism and the hippy generation of hedonistic values mushrooming in shallow themes of ‘non-repression’. (Shepherd, Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals, 2004, p. 98)

For a more sustained critique of Wilber’s neoperennialism, see Shepherd, Pointed Observations (2005) pp. 45-73, being written well in advance of the “Wild West” showdown. Cf. the multi-volume Collected Works of Ken Wilber.

The anti-ascetic bias of American pseudo-integralism is a "closed mind" avenue contrasting with "big mind" historical research into groupings such as the Manichaeans. The semi-legendary Mani (216-277 CE) was a Syriac-speaking inhabitant of the Sassanian Empire, a man reared in a Jewish-Christian "baptist" community. His following spread rapidly in various directions. Manichaean monks and nuns were supported by lay adherents, similar to operation of the Buddhist sangha, apparently an influence at work here. Mani included diverse religions in his ideological system; he was perhaps more of an integralist than Ken Wilber. His religion, of a transmigrationist contour, opposed blood sacrifices and meat consumption.

Archaeological research at the Dakhleh Oasis, in Upper Egypt, has revealed the village of Kellis in a Manichaean perspective. An emerging study of social organisation here, amongst lay Manicheans of the fourth century CE, is more relevant than dismissive American "integralist" judgments. Manichaean affiliation was widespread in mercantile sectors, and apparently extended into artisan ranks (Hakon F. Teigen, The Manichaean Church at Kellis, Leiden 2021). The Manichaean religion also exercised a fascination for intellectuals, including Christians. The degree of suppression was formidable, both Roman and Sassanian officials proving violently intolerant of Manichaeans.

Mahayana separatists like Ken Wilber have failed to grasp that the Hinayana trends in early Buddhism were a complex phenomenon. An "integralist" figurehead, the legendary Nagarjuna (born a Hindu), could easily have been a Hinayanist, more closely related to Theravada monasticism than subsequent Mahayanist doctrines. The presumed Zen sword of prajna, cutting off the heads of Wilber critics, is a preferred scenario described by Wilber in lewd Wild West terms of "ripping their eyes out and pissing in their eye-sockets." This vulgar integralism is an unconvincing gauge for a claimed "History of Everything."

Wilber chooses to overlook the fact that Mahayana traditions like Zen (Chan) were monastic. Similarly, Advaita Vedanta was maintained in the renunciate sector of India; there was no recognised alternative. An unwelcome detail to many entrepreneurs is that Asiatic "wisdom traditions" did not exist in the mould of American workshop commerce.

The degraded “perennial philosophy” is currently in the secondary category of affluent leisure interests. The aborted ahistorical subject, to become relevant, would need to be divested of contemporary biases and distortions. Judging by current standards, that might take a long time. By then, the American consumerist lifestyle (and alleged "human potential") could be in a severe predicament, not least because of factors arising from the climate change so often ignored by politicians.

The "post-metaphysical" exegesis of Wilber, departing from the caricatured perennial philosophy, is one of the issues covered in Ken Wilber and Integralism. See also Ken Wilber and Integral Theory.

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved. Page uploaded September 2008, last modified July 2021.