Perennial Phil Ch 5 CHARITY [11,5695]

He that loveth not knoweth not God, for God is love.

By love may He be gotten and holden, but by thought never.

Whosoever studies to reach contemplation (i.e. unitive knowledge) should begin by searchingly enquiring of himself how much he loves. For love is the motive power of the mind (mackina mends), which draws it out of the world and raises it on high.

The astrolabe of the mysteries of God is love.

Let the superfluous and lust-dieted man

That slaves your ordinance, that will not see

Because he doth not feel, feel your power quickly.

Love is infallible; it has no errors, for all errors are the want of love.

WE can only love what we know, and we can never know completely what we do not love. Love is a mode of knowledge, and when the love is sufficiently disinterested and sufficiently intense, the knowledge becomes unitive knowledge and so takes on the quality of infallibility.

Here on earth the love of God is better than the knowledge of God, while it is better to know inferior things than to love them. By knowing them we raise them, in a way, to our intelligence, whereas by loving them we stoop towards them and may become subservient to them, as the miser to his gold.

[ 97]

This remark seems, at first sight, to be incompatible with what precedes it. But in reality St. Thomas is merely distinguishing between the various forms of love and knowledge. It is better to love-know God than just to know about God, without love, through the reading of a treatise on theology.

We make an idol of truth itself; for truth apart from charity is not God, but his image and idol, which we must neither love nor worship.

By a kind of philological accident (which is probably no accident at all, but one of the more subtle expressions of man's deep-seated will to ignorance and spiritual darkness), the word 'charity' has come, in modem English, to be synonymous with 'almsgiving,' and is almost never used in its original sense, as signifying the highest and most divine form of love.

Love seeks no cause beyond itself and no fruit; it is its own fruit, its own enjoyment. I love because I love; I love in order that I may love.... Of all the motions and affections of the soul, love is the only one by means of which the creature, though not on equal terms, is able to treat with the Creator and to give back something resembling what has been given to it. . . . When God loves, He only desires to be loved, knowing that love will render all those who love Him happy.

For as love has no by-ends, wills nothing but its own increase, so everything is as oil to its flame; it must have that which it wills and carnxot be disappointed, because everything (including Unkindness on the part of those loved) naturally helps it to live in its own way and to bring forth its own work.

[ 99]

Those who speak ill of me are really my good friends. [?]

When, being slandered, I cherish neither enmity nor preference, There grows within me the power of love and humility, which is born of the Unborn.

Some people want to see God with their eyes as they see a cow, and to love Him as they love their cow—for the milk and cheese and profit it brings them. This is how it is with people who love God for the sake of outward wealth or inward comfort. They do not rightly love God, when they love Him for their own advantage. Indeed, I tell you the truth, any object you have in your mind, however good, will be a barrier between you and the inmost Truth.

A beggar, Lord, I ask of TheeMore than a thousand kings could ask.Each one wants something, which he asks of Thee.I come to ask Thee to give me Thyself.

I will have nothing to do with a love which would be for God or in God. This is a love which pure love cannot abide; for pure love is God Himself.

As a mother, even at the risk of her own life, protects her son, her only son, so let there be good will without measure between all beings. Let good will without measure prevail in the whole world, above, below, around, unstinted, unmixed with any feeling of differing or opposing interests. If a man remain steadfastly in this state of mind all the time he is awake, then is come to pass the saying, 'Even in this world holiness has been found.'

Learn to look with an equal eye upon all beings, seeing the one Self in all.

Sri,nad Bliagavatam

[100]

The second distinguishing mark of charity is that, unlike the lower forms of love, it is not an emotion. It begins as an act of the will and is consummated as a purely spiritual awareness, a unitive love-knowledge of the essence of its object.

Let everyone understand that real love of God does not consist in tear-shedding, nor in that sweetness and tenderness for which usually we long, just because they console us, but in serving God in justice, fortitude of soul and humility.

The worth of love does not consist in high feelings, but in detachment, in patience under all trials for the sake of God whom we love.

St. John of the CrossBy love I do not mean any natural tenderness, which is more or less in people according to their constitution; but I mean a larger principle of the soul, founded in reason and piety, which makes us tender, kind and gentle to all our fellow creatures as creatures of God, and for his sake.

The nature of charity, or the love-knowledge of God, is defined by Shankara, the great Vedantist saint and philosopher of the ninth century, in the thirty-second couplet of his Viveka-Cliudamani.

Among the instruments of emancipation the supreme is devotion.

In other words, the highest form of the love of God is an immediate spiritual intuition, by which 'knower, known and knowledge are made one.' [ 101]

- towards the denial of self-ness in thought, feeling and action,

- towards desirelessness and non-attachment or (to use the corresponding Christian term) 'holy indifference,'

- towards a cheerful acceptance of affliction, without self-pity and without thought of returning evil for evil, and finally

- towards unsleeping and one-pointed mindfulness of the Godhead who is at once transcendent and, because transcendent, immanent in every soul.

It is plain that no distinct object whatever that pleases the will can be God; and, for that reason, if the will is to be united with Him, it must empty itself, cast away every disorderly affection of the desire, every satisfaction it may distinctly have, high and low, temporal and spiritual, so that, purified and cleansed from all unrully satisfactions, joys and desires, it may be wholly occupied, with all its affections, in loving God.

For if the will can in any way comprehend God and be united with Him, it cannot be through any capacity of the desire, but only by love; and as all the delight, sweetness and joy, of which the will is sensible, is not love, it follows that ione of these pleasing impressions can be the adequate means of uniting the will to God. These adequate means consist in an act of the will.

And because an act of the will is quite distinct from feeling, it is by an act that the will is united with God and rests in Him; that act is love. This union is never wrought by feeling or exertion of the desire; for these remain in the soul as aims and ends. It is only as motives of love that feelings can be of service, if the will is bent on going onwards, and for nothing else....

He, then, is very unwise who, when sweetness and spiritual delight fail him, thinks for that reason that God has abandoned him; and when he finds them again, rejoices and is glad, thinking that he has in that way come to possess God.

More unwise still is he who goes about seeking for sweetness in God, rejoices in it, and dwells upon it; for in so doing he is not seeking after God with the will grounded in the emptiness of faith and charity, but only in spiritual sweetness and delight, which is a created thing, following herein in his own will and fond pleasure. . . . It is impossible for the will to attain to the sweetness and bliss of the divine union otherwise than- in detachment, in refusing to the desire every pleasure in the things of heaven and earth.

Love (the sensible love of the emotions) does not unify.

True, it unites in act; but it does not unite in essence.

The reason why sensible love even of the highest object cannot unite the soul to its divine Ground in spiritual essence is that, like all other emotions of the heart, sensible love intensifies that selfness, which is the final obstacle in the way of such union. 'The damned are in eternal movement without any mixture of rest;

It is by means of tranquillity of mind that you are able to transmute this false mind of death and rebirth into the clear Intuitive Mind and, by so doing, to realize the primal and enlightening Essence of Mind. You should make this your starting point for spiritual practices. Having harmonized your starting point with your goal, you will be able by right practice to attain your true end of perfect Enlightenment.

If you wish to tranquilize your mind and restore its original purity, you must proceed as you would do if you were purifying a jar of muddy water. You first let it stand, until the sediment settles at the bottom, when the water will become clear, which corresponds with the state of the mind before it was troubled by defiling passions. Then you carefully strain off the pure water. When the mind becomes tranquillized and concentrated into perfect unity, then all things will be seen, not in their separateness, but in their unity, wherein there is no place for the passions to enter, and which is in full conformity with the mysterious and indescribable purity of Nirvana.

This identity out of the One into the One and with the One is the source and fountainhead and breaking forth of glowing Love.

Spiritual progress, as we have had occasion to discover in several other contexts, is always spiral and reciprocal.

Would you become a pilgrim on the road of Love?The first condition is that you make yourself humble as dust and ashes.

[104]

I have but one word to say to you concerning love for your neighbour, namely that nothing save humility can mould you to it; nothing but the consciousness of your own weakness can make you indulgent and pitiful to that of others. You will answer, I quite understand that humility should produce forbearance towards others, but how am I first to acquire humility? Two things combined will bring that about; you must never separate them. The first is contemplation of the deep gulf; whence God's all-powerful hand has drawn you out, and over which He ever holds you, so to say, suspended. The second is the presence of that all-penetrating God. It is only in beholding and loving God that we can learn forgetfulness of self, measure duly the nothingness which has dazzled us, and accustom ourselves thankfully to decrease beneath that great Majesty which absorbs all things. Love God and you will be humble; love God and you will throw off the love of self; love God and you will love all that He gives you to love for love of Him.

Feelings, as we have seen, may be of service as motives of charity;

- —will to peace and humility in oneself,

- will to patience and kindness towards one's fellow-creatures,

- will to that disinterested love of God which 'asks nothing and refuses nothing.'

I once asked the Bishop of Geneva what one must do to attain perfection. 'You must love God with all your heart,' he answered, 'and your neighbour as yourself.' [ 105]'I did not ask wherein perfection lies,' I rejoined, 'but how to attain it.' 'Charity,' he said again, 'that is both the means and the end,

the only way by which we can reach that perfection

which is, after all, but Charity itself. . . .

Just as the soul is the life of the body, so charity is the life of the soul.'

'I know all that,' I said. 'But I want to know how one is to love God with all one's heart and one's neighbour as oneself.'

But again he answered, 'We must love God with all our hearts, and our neighbour as ourselves.'

'I am no further than I was,' I replied. 'Tell me how to acquire such love.'

'The best way, the shortest and easiest way of loving God with all one's heart is to love Him wholly and heartily!'

He would give no other answer. At last, however, the Bishop said, 'There are many besides you who want me to tell them of methods and systems and secret ways of becoming perfect, and I can only tell them that the sole secret is a hearty love of God, and the only way of attaining that love is by loving.

You learn to speak by speaking, to study by studying, to run by running, to work by working; and just so you learn to love God and man by loving.

All those who think to learn in any other way deceive themselves. If you want to love God, go on loving Him more and more. Begin as a mere apprentice, and the very power of love will lead you on to become a master in the art. Those who have made most progress will continually press on, never believing themselves to have reached their end; for charity should go on increasing until we draw our last breath.'

The passage

Those men who in a special way regard Heaven as Father and have, as it were, a personal love for it, how much more should they love what is above Heaven as Father! Other men in a special way regard their rulers as better than themselves and they, as it were, personally die for them. How much more should they die for what is truer than a ruler! When the springs dry up, the fish are all together on dry land. They then moisten each other with their dampness and keep each other wet with their slime. But this is not to be compared with forgetting each other in a river or lake.

The slime of personal and emotional love is remotely similar to the water of the Godhead's spiritual being, but of inferior quality and (precisely because the love is emotional and therefore personal) of insufficient quantity. Having, by their voluntary ignorance, wrong-doing and wrong being, caused the divine springs to dry up, human beings can do something to mitigate the horrors of their situation by 'keeping one another wet with their slime.' But there can be no happiness or safety in time and no deliverance into eternity, until they give up thinking that slime is enough and, by abandoning themselves to what is in fact their element, call back the eternal waters.

The sect of lovers is distinct from all others;Lovers have a religion and a faith all their own.

The soul lives by that which it loves rather than in the body which it animates. For it has not its life in the body, but rather gives it to the body and lives in that which it loves.

Temperance is love surrendering itself wholly to Him who is its object; courage is love bearing all things gladly for the sake of Him who is its object; justice is love serving only Him who is its object, and therefore rightly ruling; prudence is love making wise distinctions between what hinders and what helps itself.

The distinguishing marks of charity are disinterestedness, tranquillity and humility. But where there is disinterestedness there is neither greed for personal advantage nor fear for personal loss or punishment; where there is tranquillity, there is neither craving nor aversion, but a steady will to conform to the divine Tao or Logos on every level of existence and a steady awareness of the divine Suchness and what should be one's own relations to it; and where there is humility there is no censoriousness and no glorification of the ego or any projected alter-ego at the expense of others, who are recognized as having the same weaknesses and faults, but also the same capacity for transcending them in the unitive knowledge of God, as one has oneself. From all this it follows that charity is the root and substance of morality, and that where there is little charity there will be much avoidable evil. All this has been summed up in Augustine's formula: 'Love, and do what you like.'[108]

Turn the man loose who has found the living Guide within him, and then let him neglect the outward if he can! Just as you would say to a man who loves his wife with all tenderness, "You are at liberty to beat her, hurt her or kill her, if you want to.'

From this it follows that, where there is charity, there can be no coercion.

God forces no one, for love cannot compel, and God's service, therefore, is a thing of perfect freedom.

But just because it cannot compel, charity has a kind of authority, a non-coercive power, by means of which it defends itself and gets its beneficent will done in the world—not always, of course, not inevitably or automatically (for individuals and, still more, organizations can be impenetrably armoured against divine influence), but in a surprisingly large number of cases.

Heaven arms with pity those whom it would not see destroyed.

'He abused me, he beat me, he defeated me, he robbed me'—in those who harbour such thoughts hatred will never cease.'He abused me, he beat me, he defeated me, he robbed me'—in those who do not harbour such thoughts hatred will cease.For hatred does not cease by hatred at any time—this is an old rule.

Our present economic, social and international arrangements are based, in large measure, upon organized lovelessness.

'Lead us not into temptation' must be the guiding principle of all social organization, and the temptations to be guarded against and, so far as possible, eliminated by means of appropriate economic and political arrangements are temptations against charity, that is to say,

Knitter: Oh, I definitely do. I was born a Catholic in Chicago, grew up and entered the seminary. I consider myself to be a Christian, especially in its Roman Catholic form.

Knitter: Oh, I definitely do. I was born a Catholic in Chicago, grew up and entered the seminary. I consider myself to be a Christian, especially in its Roman Catholic form.

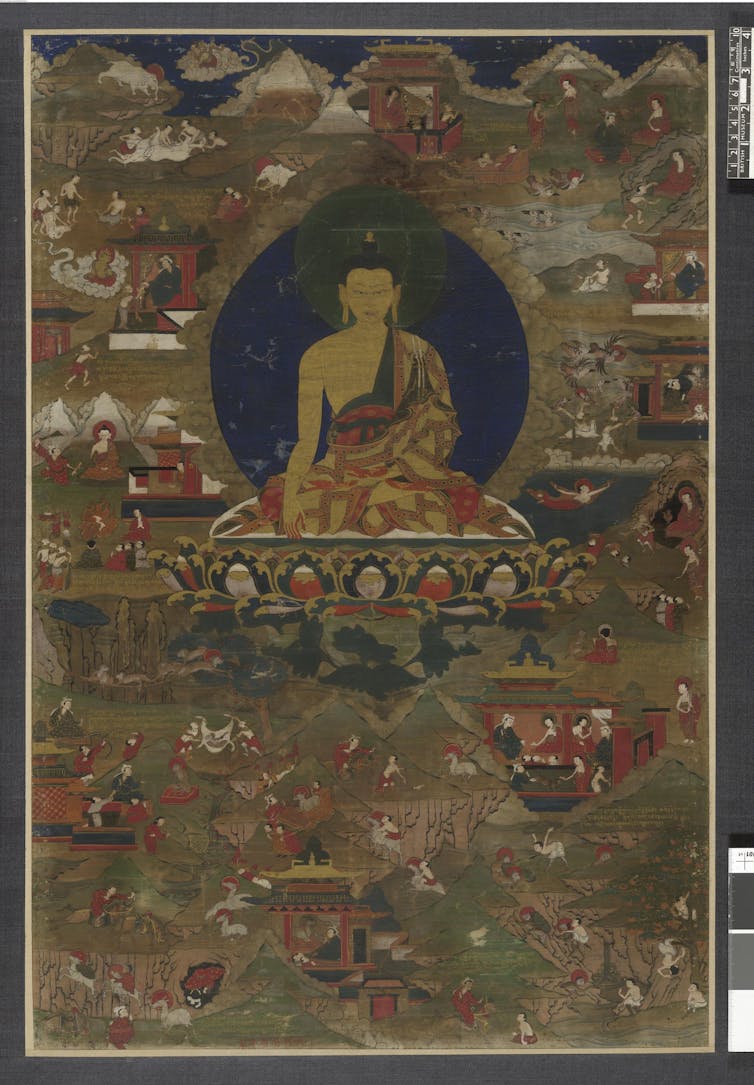

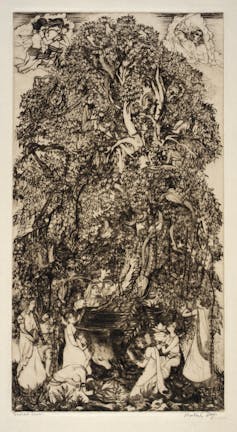

The Sacred Bodhi Tree.

The Sacred Bodhi Tree.