- tangential energy/energy of attraction and

- radial energy/energy of transcendence―

2021/07/19

A Hunger for Wholeness: Soul, Space, and Transcendence: Delio OSF, Ilia

2021/07/18

3] The Worldview of Thomas Berry: The Flourishing of the Earth Community | Coursera

The Worldview of Thomas Berry: The Flourishing of the Earth Community

4.7

stars

118 ratings

•

31 reviews

John Grim +1 more instructor

John Grim +1 more instructor Enroll for Free

Starts Jul 18

Financial aid available

5,592 already enrolled

Offered By

About

Instructors

Syllabus

Reviews

Enrollment Options

FAQ

About this Course

3,311 recent views

Thomas Berry (1914-2009) was a historian of world religions and an early voice awakening moral sensibilities to the environmental crisis. He is known for articulating a “new story” of the universe that explores the implications of the evolutionary sciences and cultural traditions for creating a flourishing future.

This course investigates Berry’s life and thought in relation to the Journey of the Universe project. It draws on his books, articles, and recorded lectures to examine such ideas as: the New Story, the Great Work, and the emerging Ecozoic era. The course explores Berry’s insights into cosmology as a context for locating the human in a dynamic unfolding universe and thus participating in the creative work of our times. In particular, we will examine Berry’s reflections on renewal and reform in the areas of ecology, economics, education, spirituality, and the arts. Course Rationale: Thomas Berry was an original, creative, and comprehensive thinker, especially regarding the critical nature of our global environmental crisis. His intellectual importance resides in his response to the ecological crisis by bringing together the humanities and science in an evolutionary narrative. In addition, he articulated the need for the moral participation of the world religions in addressing environmental issues. He came to this realization largely through his study of cosmologies embedded within religious traditions. Sensing the significance of these stories as “functional cosmologies” he explored the widespread influence that these stories transmitted through a tradition, for example, in rituals, ethics, and subsistence practices.

Flexible deadlines

Reset deadlines in accordance to your schedule.

Shareable Certificate

Earn a Certificate upon completion

100% online

Start instantly and learn at your own schedule.

Approx. 25 hours to complete

English

Subtitles: French, Portuguese (European), Chinese (Simplified), Russian, English, Spanish

Offered by

Yale University

For more than 300 years, Yale University has inspired the minds that inspire the world. Based in New Haven, Connecticut, Yale brings people and ideas together for positive impact around the globe. A research university that focuses on students and encourages learning as an essential way of life, Yale is a place for connection, creativity, and innovation among cultures and across disciplines.

Syllabus - What you will learn from this course

Content Rating99%(1,216 ratings)

WEEK1

1 hour to complete

Welcome to The Worldview of Thomas Berry: the Flourishing of the Earth Community

Learn what this course is about, who's teaching it, and other ways you can explore this topic. Meet and greet your peers as well!

1 video (Total 11 min), 6 readingsSEE LESS

1 video

Course Introduction10m

6 readings

Course Description10m

Pre-Course Survey10m

Meet Your Instructional Team10m

Recommended Texts10m

Books of Thomas Berry10m

Additional Berry resources10m

3 hours to complete

Introduction - Thomas Berry as Cultural Historian

Mary Evelyn and John talk about their first encounters with Thomas Berry.

3 videos (Total 54 min), 2 readings, 2 quizzesSEE LESS

3 videos

Dialogue: Tucker and Grim, “The Worldview of Thomas Berry”22m

“Thomas Berry Speaks,” filmed by Marty Ostrow27m

Brian Swimme's Thomas Berry intro3m

2 readings

“Life and Thought: Introduction,” by J Grim and ME Tucker15m

Thomas Berry Website20m

2 practice exercises

Thomas Berry as a Cultural Historian30m

Introduction - Thomas Berry as Cultural Historian30m

WEEK2

5 hours to complete

Thomas Berry’s Study of World Cultures and Religions

Thomas Berry was a scholar of Earth’s cultures; someone who inspired others to understand that the scientific story of the universe was a primary revelation, on the part with the world’s religions, and needing to be integrated with world’s cultures.

6 videos (Total 128 min), 4 readings, 2 quizzesSEE LESS

6 videos

Tucker and Grim, “Thomas Berry and the Encounter with World Religions.22m

(Part 1) “The Universe and Religion” by Thomas Berry13m

(Part 2) “The Universe and Religion” by Thomas Berry11m

(Part 3) “The Universe and Religion” by Thomas Berry31m

(Part 4) “The Universe and Religion” by Thomas Berry45m

Thomas Berry, a Scholar of World Cultures3m

4 readings

Forum on Religion and Ecology20m

Thomas Berry: Selected Writings on the Earth Community (Chapter 5)30m

Thomas Berry: Selected Writings on the Earth Community (Chapter 6)30m

Asian Art Highlights from Yale University Art Gallery15m

2 practice exercises

Thomas Berry’s Study of World Cultures and Religions30m

Thomas Berry’s Study of World Cultures and Religions30m

WEEK3

3 hours to complete

Influence of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Learn how Pierre Teilhard de Chardin inspired Thomas Berry. Discover Special Relativity as a way of showing the omnipresence of the “within.”

3 videos (Total 47 min), 3 readings, 2 quizzesSEE LESS

3 videos

(Part 1) Teilhard de Chardin in an Age of Ecology,” an interview of Thomas Berry with Jane Blewett20m

(Part 2) Teilhard de Chardin in an Age of Ecology,” an interview of Thomas Berry with Jane Blewett23m

Teilhard de Chardin's influence on Berry's thoughts3m

3 readings

“Teilhard in the Ecological Age,” by Thomas Berry, in Teilhard in the 21st Century. Edited by Arthur Fabel and Donald St John, Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 200310m

Audio: Thomas Berry on Teilhard de Chardin at the Cathedral of St John the Divine, NYC.32m

Teilhard Association Websites30m

2 practice exercises

Teilhard de Chardin in the Age of Ecology30m

Influence of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin30m

WEEK4

3 hours to complete

“The New Story”

Thomas Berry’s Differentiation, Subjectivity, and Communion as the overall guidance the New Story provides for humanity.

3 videos (Total 45 min), 3 readings, 2 quizzesSEE LESS

3 videos

(Part 1) “The New Story,” by Thomas Berry18m

(Part 2) “The New Story,” by Thomas Berry21m

Differentiation, Subjectivity, and Communion4m

3 readings

"The New Story," by Thomas Berry, Teilhard Studies #1, Teilhard Association, Winter 1978.20m

Chapter 1 from Thomas Berry: Selected Writings on the Earth Community20m

Journey of the Universe website10m

2 practice exercises

Thomas Berry's New Story30m

“The New Story”30m

Show More

Reviews

4.7

31 reviews

5 stars

83.89%

4 stars

11.01%

3 stars

1.69%

2 stars

0.84%

1 star

2.54%

TOP REVIEWS FROM THE WORLDVIEW OF THOMAS BERRY: THE FLOURISHING OF THE EARTH COMMUNITY

by MDec 7, 2019

I have just completed the 3-course specialization that included this course. All excellent, inspirational, and hopeful. This content is essential for emergence into the Ecozoic Era.

by USJun 23, 2019

I love Thomas Berry and they way he is able to tell us the story of the universe. This is an amazing course, an eye opener and a spiritual journey overall. Thank You.

by TASep 29, 2017

This course will give new insight, grand thought concerning everything, the all things exist in the universe, to you. I want you to have these things as I have.

by JBMar 20, 2017

A fantastic course that deepened my understanding of the brilliant thought of Thomas Berry, bringing to life his personal story and the stories he told.View all reviews

2021/06/19

Encyclopedia of Western Theology: Wolfhart Pannenberg

Pannenberg, WolfhartContents Wolfhart Pannenberg (1928- ) (Peter Heltzel, 1999)

Wolfhart Pannenberg (1928- )Peter Heltzel, 1999

Formation of a Philosophical TheologianRecovering essential philosophical tools and concepts in a post-Ritshclian German Lutheran confessional context, Pannenberg was able to reestablish the public platform of the discipline of theology in the broader cross-disciplinary conversation of our day. He was prepared to take on a project of this magnitude through a variety of personal and educational experiences in his youth. Wolfhart Pannenberg was born in 1928 in Stettin, Germany (modern day Poland). Although baptized a Lutheran as an infant, during his childhood he had almost no contact with the church. However, during his youth he did have an intense religious experience which he refers to as his "light experience." Placed in the categories of his later theology, his religious experience would be classified as an unthematic experience of God very similar to Rahner’s understanding of religious experience (Pannenberg 1981: 260). A curious lad, Pannenberg sought to understand his experience through reading the great philosophers and religious thinkers. Moreover, one of his teachers proved to be an important influence in Pannenberg’s conversion to the Christian worldview. He encountered this literature teacher, who had been a member of the Confessing Church during the Third Reich, during his final years of high school. This instructor convinced him to take a long hard look at Christianity, a thoughtful period of Pannenberg’s life when he concluded that Christianity was the best philosophy. This "intellectual conversion" launched him into a vocation as a Christian theologian (Pannenberg 1981: 261). Pannenberg began his theological studies after the Second World War at the University of Berlin, studying and teaching throughout his life at some of the greatest institutions in Germany. He would continue his theological investigations at the Universities of Gh ttingen and Basle. At the University of Heidelberg he completed his doctoral dissertation on the doctrine of predestination of the noted medieval scholastic theologian John Duns Scotus (published in 1954) under the supervision of the Lutheran Barthian Edmund Schlink, and in 1955 completed his Habilitationsschrift with an analysis of the role of analogy in Western thought up to Thomas Aquinas (Tupper 1974 :19-44). While Pannenberg was at Basle he studied under Karl Barth, the leading Protestant theologian of his day. Pannenberg appreciated Barth’s Word of God theology which was a post-Kantian renewal of the Reformation theologies of John Calvin and Martin Luther. However, even as a student, Pannenberg sensed that Barth’s stringent critique of natural theology was too radical. Pannenberg’s study of the Medievals made him more sympathetic to God’s general revelation through creation. He was able to work this idea out first in the field of history, through a neo-Hegelian philosophy of history, and later in his work in religion and science. Eventually he was able to draw these two threads together in his life work: a three volume systematic theology. Philosophy of HistoryPannenberg was able to explore his interest in philosophy of history during his first teaching appointment at the University of Heidelberg, where he remained until called to a vacant chair of systematic theology at the Kirchliche Hochschule at Wuppertal (1958-61) as a colleague of Jh rgen Moltmann. After a period at the University of Mainz (1961-8), he moved to and would retire at the University of Munich, where he was also director of the Ecumenical Institute until 1993 (Pannenberg 1981: 260-263). Throughout his academic career Pannenberg was able to continue to refine a very sophisticated philosophy of history. Universal history was of great theological importance for Pannenberg because it was there in the great acts of God in history that Pannenberg argued that God was known indirectly. For Pannenberg God conducts his self-disclosure through his decisive divine deeds, primarily those in the history of Israel and in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. This focus and language of the "act of God" is straight out of the Barthian corpus. Like Barth, Pannenberg emphasizes that the content of revelation is God himself. Barth and Pannenberg agree on that basic Athanasian assertion that God reveals his being through his act, and these two are in a certain sense inseparable. However, for Barth the act of God is a direct a-temporal gift of grace in Jesus Christ, while for Panneberg God’s acts throughout history indirectly reveal himself, supremely in the resurrection. In Barth’s theology the pre-temporal election of the church willed by God before the foundation of the world (I Peter 1:19, 20: but with precious blood, as of a lamb unblemished and spotless, the blood of Christ. For He was foreknown before the foundation of the world) is the a-temporal decisive act of God which fully manifests to humanity in the incarnate Jesus Christ through the graceful illumination of the Holy Spirit. The distinctively Christian understanding of revelation for Pannenberg lies in the way in which publicly available events are interpreted. Pannenberg reasserts the importance of historicity in revelation of God. The resurrection of Jesus is a publicly accessible, objective event in history for Pannenberg. Through the resurrection all people have indirect knowledge of God. Part of the reason for the indirection in Pannenberg’s historical program is his eschatological orientation which asserts that the church will not know God directly until the consummation. For Pannenberg "history" is revelation, while "dialectical presence" is revelation for Barth. Both Pannenberg and Barth provide constructive alternatives to the two revelatory options of their day. The most recent understanding of revelation was "inner experience" as expressed in Schleiermacher’s focus on God-consciousness. Doctrine as revelation is the more traditional model, whether they be the "timeless truths" of only the Scripture (traditional Lutheran theology) or of church doctrine (the Catholic theology of Trent) or a blend of the two (as in Vatican 2). Pannenberg’s proposal is interesting because he is truly doing constructive theology trying to get beyond the impasse of Schleiermacher’s subjective pietism and Barth’s "revelational positivism". The question is does he succeed? This is an open question; however, his acceptance by both conservative and liberal theologians demonstrates that his synthesis has succeeded on the level of theological reconciliation. He is embraced by the liberals because he does not run from the problems of philosophy of history pointed out by Troeltsch like relativismus, while he is likewise embraced by the conservatives because of his orthodox Christology and Soteriology. However one evaluates Pannenberg’s project, contemporary theologians have much to learn through a dialogue with his method, epistemology and philosophy of history and science. Philosophy of ScienceDuring the 1970s Pannenberg began to express an interest in the way in which theology relates to the natural sciences. Two papers dating from the period 1971-2 focus on the approach of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and show a clear interest in the general issue of the formulation of a "theology of nature." In one sense, this can be seen as a direct extension of his earlier interest in history. Just as he appealed to the publicly observable sphere of history in his theological analysis of the 1960s, so he appeals to another publicly observable sphere, the world of nature, from the 1970s onwards. Both history and the natural world are available to scrutiny by anyone; the critical question concerns how they are to be understood. Pannenberg sees a necessary connection and interplay between scientific and religious accounts of the world. Pannenberg is clear that the natural sciences and theology are distinct disciplines, with their own understanding of how information is gained and assessed. Nevertheless, both relate to the same publicly observable reality, and they therefore have potentially complementary insights to bring. The area of the "laws of nature" is a case in point, in that Pannenberg believes that the provisional explanations for such laws offered by natural scientist have a purely provisional status, until they are placed on a firmer theoretical foundation by theological analysis. There is thus a clear case to be made for a creative and productive dialogue between the natural sciences and religion; indeed, had this taken place in the past, much confusion and tension could have avoided. Philosophy of Theology: Systematic TheologyIn the Spring of 1988 Pannenberg published the first volume of his Systematic Theology, comprising the prolegomena to dogmatics and the doctrine of God. The six chapters of volume one explore:

In this work we see a mature Pannenberg who has been able to fulfill his programmatic reflections in Revelation as History. In 1991 and 1993 followed the second and third volumes on christology and the church. The primary theme of his systematic theology is truth. In order to externally verify the truth claims of Christianity, a reflective framework must be established philosophically. For Pannenberg, neither repetition of biblical axioms nor an existential leap of faith go far enough to prove the truth of Christianity. Theological discourse about God requires a relationship to metaphysical reflection if its claim to truth is to be valid. (1990: 6). Metaphysics provides an ideational superstructure in which to assert and evaluate truth claims. These claims are necessary in establishing theological discourse, because in Christian theology everything depends on the reality of God (1991:5). For example, since Pannenberg believes in the truth of the biblical narratives he prefers to refer to them as history, instead of mere "stories" as has become fashionable among contemporary narrative theologians. By centering his project on the primacy and possibility of the norm of truth, Pannenberg stands against much of the anti-realist, subjectivist postmodernists like Richard Rorty. Although Pannenberg is a realist, he is a realist of a particular stripe, namely an eschatological realist. He believes that there really is a capital T truth out there, but that we will not know it completely until consummation of the ages, the end of the eschaton. Since all any human knower including a theologian ever has is a provisional perception of truth, all theological statements are tentative, not fully revealing and in that sense hypothetical. For Pannenberg, "History, in all its totality, can only be understood when it is viewed from its endpoint. This point alone provides the perspective from which the historical process can be seen in its totality, and thus properly understood….The end of history is disclosed proleptically in the history of Jesus Christ. In other words, the end of history, which has yet to take place, has been disclosed in advance of the event in the person and work of Christ" (McGrath, 1998, 303). Reality finds its ground in a rapidly approaching future. It is in this future that Christian hope finds its epicenter. Pannenberg’s eschatological realism offers a dynamic sense of the Kingdom of God. The Kingdom coming from the future is what is unique to the Christian apocalypse—unveiling--of God’s reign, a righteous rule of love and justice. ConclusionPannenberg is well situated among the great contemporary Protestant theologians. On the one hand, he is clearly a confessional Lutheran "Word of God" theologian. Yet, on the other hand, from a methodological point of view he is a post-Enlightenment liberal. His attempt to bring together Lutheran tradition with a contemporary method is what makes his theology so interesting and compelling. One important legacy that Panneberg will leave for young theologians at the turn of the century is an interdisciplinary paradigm for constructing theology. Pannenberg’s Systematic Theology is a brilliant presentation of an authentically Christian and intellectually plausible view of reality, developed in intradisciplinary theological cooperation and tested in interdisciplinary dialogue with other sciences. Philosophy plays a critical, muli-faceted role in theology which is conducted in this paradigm. It provides a metaphysical reflection to describe the world which is an independent locus of revelation of God. However, one variable that Pannenberg has not fully operationalized in his systematic theology is comparative theology, seeing Christian theology from the outside perspective of other theologies. Nonetheless, Pannenberg, by taking Troeltsch’s philosophical criticisms to heart, staying true to Lutheran Orthodoxy, and establishing the credibility of the Christian belief through the cannons of probable reasoning, Pannenberg has produced a post-Enlightenment Christian system which is comprehensive, credible and compelling.

BibliographyPrimary Works of PannenbergAnthropology in Theological Perspective. 1985. trans. Matthew J. O’Connell. Philadelphia: Westminster. Basic Questions in Theology. 1971. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. Trans. George H. Kelm of Grundfragen systematischer Theologie, Gesammelte Aufs@ tze. G` ttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1967. "The Doctrine of Creation and Modern Science." Zygon 23 (1988):3-21. "God’s Presence in History." 1981. Christian Century. 98:3/11:260-3. Introduction to Systematic Theology. 1991. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans. Jesus—God and Man. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1968. Trans. by Lewis L. Wilkins and Duane A. Priebe of Grundzh ge der Christologie. Gh tersloh: Gh tersloher Verlagshaus G. Mohn, 1964. Metaphysics and the Idea of God. Trans. by Philip Clayton. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. Revelation as History. 1968. coauthored with Rolf Rendtorff, Trutz Rendtorff, and Ulrich Wilkens. New York: Macmillan. Trans. David Granskow of Offenbarung als Geschichte. G` ttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1963. Systematic Theology. 1991. Vol.1. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. Trans. Geoffrey Bromiley from Systematische Theologie. 1988. Band 1. Guttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht. Theology and the Philosophy of Science. 1976. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. Trans. Francis McDonagh of Wissenschaftstheorie und Theologie. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 1973. Secondary Works Barth, Karl. 1962. Church Dogmatics, III/1, trans. G.W. Bromiley. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. Braaten, C.E., and Clayton, P. 1988. The Theology of Wolfhart Pannenberg. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Press. Hefner, P. 1989. "The Role of Science in Pannenberg’s Theological Thinking." Zygon 24: 135-51. McGrath, Alister E. Historical Theology. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998. Russell, R.J. 1988. "Contingency in Physics and Cosmology: A Critique of the Theology of Wolfhart Pannenberg." Zygon 23:23-43. Tupper, E.F. 1974. The Theology of Wolfhart Pannenberg. London. Wildman, Wesley J. 1998. Fidelity with Plausibility. New York: SUNY.

The information on this page is copyright ©1994-2008, Wesley Wildman (basic information here), unless otherwise noted. If you want to use ideas that you find here, please be careful to acknowledge this site as your source, and remember also to credit the original author of what you use, where that is applicable. If you want to use text or stories from these pages, please contact me at the feedback address for permission. |

2021/06/16

Big History - Wikipedia

Big History

This article possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (October 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

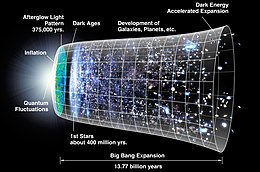

Big History is an academic discipline which examines history from the Big Bang to the present. Big History resists specialization, and searches for universal patterns or trends. It examines long time frames using a multidisciplinary approach based on combining numerous disciplines from science and the humanities,[1][2][3][4][5] and explores human existence in the context of this bigger picture.[6] It integrates studies of the cosmos, Earth, life, and humanity using empirical evidence to explore cause-and-effect relations,[7][8] and is taught at universities[9] and primary and secondary schools[10][11] often using web-based interactive presentations.[12][13][14]

Historian David Christian has been credited with coining the term "Big History" while teaching one of the first such courses at Macquarie University.[7][9][15] An all-encompassing study of humanity's relationship to cosmology[16] and natural history[17] has been pursued by scholars since the Renaissance, and the new field, Big History, continues such work.

Contents

Comparison with conventional history[edit source]

| Conventional history | Big History |

| 5000 BCE to present | Big Bang to present |

| 7,000–10,000 years | 13.8 billion years |

| Compartmentalized fields of study | Interdisciplinary approach |

| Focus on human civilization | Focus on how humankind fits within the universe |

| Taught mostly with books | Taught on interactive platforms at: Coursera, Youtube's Crash Course, Big History Project, Macquarie University, ChronoZoom |

| Microhistory | Macrohistory |

| Focus on trends, processes | Focus on analogy, metaphor |

| Based on a variety of documents, including written records and material artifacts | Based on current knowledge about phenomena such as fossils, ecological changes, genetic analysis, telescope data, in addition to conventional historical data |

Big History examines the past using numerous time scales, from the Big Bang to modernity,[4] unlike conventional history courses which typically begin with the introduction of farming and civilization,[18] or with the beginning of written records. It explores common themes and patterns.[12] Courses generally do not focus on humans until one-third to halfway through,[7] and, unlike conventional history courses, there is not much focus on kingdoms or civilizations or wars or national borders.[7] If conventional history focuses on human civilization with humankind at the center, Big History focuses on the universe and shows how humankind fits within this framework[19] and places human history in the wider context of the universe's history.[20][21]

Unlike conventional history, Big History tends to go rapidly through detailed historical eras such as the Renaissance or Ancient Egypt.[22] It draws on the latest findings from biology,[4] astronomy,[4] geoscience,[4] chemistry, physics, archaeology, anthropology, psychology, sociology, economics,[4] prehistory, ancient history, and natural history, as well as standard history.[23] One teacher explained:

We're taking the best evidence from physics and the best evidence from chemistry and biology, and we're weaving it together into a story ... They're not going to learn how to balance [chemical] equations, but they're going to learn how the chemical elements came out of the death of stars, and that's really interesting.[12]

Big History arose from a desire to go beyond the specialized and self-contained fields that emerged in the 20th century. It tries to grasp history as a whole, looking for common themes across multiple time scales in history.[24][25] Conventional history typically begins with the invention of writing, and is limited to past events relating directly to the human race. Big Historians point out that this limits study to the past 5,000 years and neglects the much longer time when humans existed on Earth. Henry Kannberg sees Big History as being a product of the Information Age, a stage in history itself following speech, writing, and printing.[26] Big History covers the formation of the universe, stars, and galaxies, and includes the beginning of life as well as the period of several hundred thousand years when humans were hunter-gatherers. It sees the transition to civilization as a gradual one, with many causes and effects, rather than an abrupt transformation from uncivilized static cavemen to dynamic civilized farmers.[27] An account in The Boston Globe describes what it polemically asserts to be the conventional "history" view:

Early humans were slump-shouldered, slope-browed, hairy brutes. They hunkered over campfires and ate scorched meat. Sometimes they carried spears. Once in a while they scratched pictures of antelopes on the walls of their caves. That's what I learned during elementary school, anyway. History didn't start with the first humans—they were cavemen! The Stone Age wasn't history; the Stone Age was a preamble to history, a dystopian era of stasis before the happy onset of civilization, and the arrival of nifty developments like chariot wheels, gunpowder, and Google. History started with agriculture, nation-states, and written documents. History began in Mesopotamia's Fertile Crescent, somewhere around 4000 BC. It began when we finally overcame our savage legacy, and culture surpassed biology.[27]

Big History, in contrast to conventional history, has more of an interdisciplinary basis.[12] Advocates sometimes view conventional history as "microhistory" or "shallow history", and note that three-quarters of historians specialize in understanding the last 250 years while ignoring the "long march of human existence."[2] However, one historian disputed that the discipline of history has overlooked the big view, and described the "grand narrative" of Big History as a "cliché that gets thrown around a lot."[2] One account suggested that conventional history had the "sense of grinding the nuts into an ever finer powder."[23] It emphasizes long-term trends and processes rather than history-making individuals or events.[2] Historian Dipesh Chakrabarty of the University of Chicago suggested that Big History was less politicized than contemporary history because it enables people to "take a step back."[2] It uses more kinds of evidence than the standard historical written records, such as fossils, tools, household items, pictures, structures, ecological changes and genetic variations.[2]

Criticism of Big History[edit source]

Critics of Big History, including sociologist Frank Furedi, have deemed the discipline an "anti-humanist turn of history."[28] The Big History narrative has also been challenged for failing to engage with the methodology of the conventional history discipline. According to historian and educator Sam Wineburg of Stanford University, Big History eschews the interpretation of texts in favor of a purely scientific approach, thus becoming "less history and more of a kind of evolutionary biology or quantum physics."[29] Others have pointed out that such criticisms of Big History removing the human element or not following a historical methodology seem to derive from observers who have not sufficiently looked into what Big History actually does, with most courses having one-third or half devoted to humanity, with the concept of increasing complexity giving humanity an important place, and with methods in the natural sciences being innately historical since they also attempt to gather evidence in order to craft a narrative.[30]

Themes[edit source]

Big History seeks to retell the "human story" in light of scientific advances by such methods as radiocarbon dating, genetic analysis, thermodynamic measurements of "free energy rate density", along with a host of methods employed in archaeology, anthropology, and world history. David Christian of Macquarie University has argued that the recent past is only understandable in terms of the "whole 14-billion-year span of time itself."[23] David Baker of Macquarie University has pointed out that not only do the physical principles of energy flows and complexity connect human history to the very start of the Universe, but the broadest view of human history many also supply the discipline of history with a "unifying theme" in the form of the concept of collective learning.[31] Big History also explores the mix of individual action and social and environmental forces, according to one view.[2] Big History seeks to discover repeating patterns during the 13.8 billion years since the Big Bang[1] and explore the core transdisciplinary theme of increasing complexity as described by Eric Chaisson of Harvard University.

Time scales and questions[edit source]

Big History makes comparisons based on different time scales and notes similarities and differences between the human, geological, and cosmological scales. David Christian believes such "radical shifts in perspective" will yield "new insights into familiar historical problems, from the nature/nurture debate to environmental history to the fundamental nature of change itself."[23] It shows how human existence has been changed by both human-made and natural factors: for example, according to natural processes which happened more than four billion years ago, iron emerged from the remains of an exploding star and, as a result, humans could use this hard metal to forge weapons for hunting and war.[7] The discipline addresses such questions as "How did we get here?," "How do we decide what to believe?," "How did Earth form?," and "What is life?"[4] According to Fred Spier it offers a "grand tour of all the major scientific paradigms" and helps students to become scientifically literate quickly.[20] One interesting perspective that arises from Big History is that despite the vast temporal and spatial scales of the history of the Universe, it is actually very small pockets of the cosmos where most of the "history" is happening, due to the nature of complexity.[32]

Cosmic evolution[edit source]

−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cosmic evolution, the scientific study of universal change, is closely related to Big History (as are the allied subjects of the epic of evolution and astrobiology); some researchers regard cosmic evolution as broader than Big History since the latter mainly (and rightfully) examines the specific historical trek from Big Bang → Milky Way → Sun → Earth → humanity. Cosmic evolution, while fully addressing all complex systems (and not merely those that led to humans) has been taught and researched for decades, mostly by astronomers and astrophysicists. This Big-Bang-to-humankind scenario well preceded the subject that some historians began calling Big History in the 1990s. Cosmic evolution is an intellectual framework that offers a grand synthesis of the many varied changes in the assembly and composition of radiation, matter, and life throughout the history of the universe. While engaging the time-honored queries of who we are and whence we came, this interdisciplinary subject attempts to unify the sciences within the entirety of natural history—a single, inclusive scientific narrative of the origin and evolution of all material things over ~14 billion years, from the origin of the universe to the present day on Earth.

The roots of the idea of cosmic evolution extend back millennia. Ancient Greek philosophers of the fifth century BCE, most notably Heraclitus, are celebrated for their reasoned claims that all things change. Early modern speculation about cosmic evolution began more than a century ago, including the broad insights of Robert Chambers, Herbert Spencer, and Lawrence Henderson. Only in the mid-20th century was the cosmic-evolutionary scenario articulated as a research paradigm to include empirical studies of galaxies, stars, planets, and life—in short, an expansive agenda that combines physical, biological, and cultural evolution. Harlow Shapley widely articulated the idea of cosmic evolution (often calling it "cosmography") in public venues at mid-century,[33] and NASA embraced it in the late 20th century as part of its more limited astrobiology program. Carl Sagan,[34] Eric Chaisson,[35] Hubert Reeves,[36] Erich Jantsch,[37] and Preston Cloud,[38] among others, extensively championed cosmic evolution at roughly the same time around 1980. This extremely broad subject now continues to be richly formulated as both a technical research program and a scientific worldview for the 21st century.[39][40][41]

One popular collection of scholarly materials on cosmic evolution is based on teaching and research that has been underway at Harvard University since the mid-1970s.[42]

Complexity, energy, thresholds[edit source]

Cosmic evolution is a quantitative subject, whereas big history typically is not; this is because cosmic evolution is practiced mostly by natural scientists, while big history by social scholars. These two subjects, closely allied and overlapping, benefit from each other; cosmic evolutionists tend to treat universal history linearly, thus humankind enters their story only at the most very recent times, whereas big historians tend to stress humanity and its many cultural achievements, granting human beings a larger part of their story. One can compare and contrast these different emphases by watching two short movies portraying the Big-Bang-to-humankind narrative, one animating time linearly, and the other capturing time (actually look-back time) logarithmically; in the former, humans enter this 14-minute movie in the last second, while in the latter we appear much earlier—yet both are correct.[43]

These different treatments of time over ~14 billion years, each with different emphases on historical content, are further clarified by noting that some cosmic evolutionists divide the whole narrative into three phases and seven epochs:

- Phases: physical evolution → biological evolution → cultural evolution

- Epochs: particulate → galactic → stellar → planetary → chemical → biological → cultural

This contrasts with the approach used by some big historians who divide the narrative into many more thresholds, as noted in the discussion at the end of this section below. Yet another telling of the Big-Bang-to-humankind story is one that emphasizes the earlier universe, particularly the growth of particles, galaxies, and large-scale cosmic structure, such as in physical cosmology.

Notable among quantitative efforts to describe cosmic evolution are Eric Chaisson's research efforts to describe the concept of energy flow through open, thermodynamic systems, including galaxies, stars, planets, life, and society.[44][45][46] The observed increase of energy rate density (energy/time/mass) among a whole host of complex systems is one useful way to explain the rise of complexity in an expanding universe that still obeys the cherished second law of thermodynamics and thus continues to accumulate net entropy. As such, ordered material systems—from buzzing bees and redwood trees to shining stars and thinking beings—are viewed as temporary, local islands of order in a vast, global sea of disorder. A recent review article, which is especially directed toward big historians, summarizes much of this empirical effort over the past decade.[47]

One striking finding of such complexity studies is the apparently ranked order among all known material systems in the universe. Although the absolute energy in astronomical systems greatly exceeds that of humans, and although the mass densities of stars, planets, bodies, and brains are all comparable, the energy rate density for humans and modern human society are approximately a million times greater than for stars and galaxies. For example, the Sun emits a vast luminosity, 4x1033 erg/s (equivalent to nearly a billion billion billion watt light bulb), but it also has a huge mass, 2x1033 g; thus each second an amount of energy equaling only 2 ergs passes through each gram of this star. In contrast to any star, more energy flows through each gram of a plant's leaf during photosynthesis, and much more (nearly a million times) rushes through each gram of a human brain while thinking (~20W/1350g).[48]

Cosmic evolution is more than a subjective, qualitative assertion of "one damn thing after another". This inclusive scientific worldview constitutes an objective, quantitative approach toward deciphering much of what comprises organized, material Nature. Its uniform, consistent philosophy of approach toward all complex systems demonstrates that the basic differences, both within and among many varied systems, are of degree, not of kind. And, in particular, it suggests that optimal ranges of energy rate density grant opportunities for the evolution of complexity; those systems able to adjust, adapt, or otherwise take advantage of such energy flows survive and prosper, while other systems adversely affected by too much or too little energy are non-randomly eliminated.[49]

Fred Spier is foremost among those big historians who have found the concept of energy flows useful, suggesting that Big History is the rise and demise of complexity on all scales, from sub-microscopic particles to vast galaxy clusters, and not least many biological and cultural systems in between.[50]

David Christian, in an 18-minute TED talk, described some of the basics of the Big History course.[51] Christian describes each stage in the progression towards greater complexity as a "threshold moment" when things become more complex, but they also become more fragile and mobile.[51] Some of Christian's threshold stages are:

- The universe appears, incredibly hot, busting, expanding, within a second.[51]

- Stars are born.[51]

- Stars die, creating temperatures hot enough to make complex chemicals, as well as rocks, asteroids, planets, moons, and our solar system.[51]

- Earth is created.[51]

- Life appears on Earth, with molecules growing from the Goldilocks conditions, with neither too much nor too little energy.[51]

- Humans appear, language, collective learning.[51]

Christian elaborated that more complex systems are more fragile, and that while collective learning is a powerful force to advance humanity in general, it is not clear that humans are in charge of it, and it is possible in his view for humans to destroy the biosphere with the powerful weapons that have been invented.[51]

In the 2008 lecture series through The Teaching Company's Great Courses entitled Big History: The Big Bang, Life on Earth, and the Rise of Humanity, Christian explains Big History in terms of eight thresholds of increasing complexity:[52]

- The Big Bang and the creation of the Universe about roughly 14 billion years ago[52]

- The creation of the first complex objects, stars, about 12 billion years ago[52]

- The creation of chemical elements inside dying stars required for chemically-complex objects, including plants and animals[52]

- The formation of planets, such as our Earth, which are more chemically complex than the Sun[52]

- The origin and evolution of life from roughly about 4.2 billion years ago, including the evolution of our hominine ancestors[52]

- The development of our species, Homo sapiens, about 250,000 years ago, covering the Paleolithic era of human history[52]

- The appearance of agriculture about 11,000 years ago in the Neolithic era, allowing for larger, more complex societies[52]

- The "modern revolution", or the vast social, economic, and cultural transformations that brought the world into the modern era[52]

- What will happen in the future and predicting what will be the next threshold in our history[53][54]

Goldilocks conditions[edit source]

A theme in Big History is what has been termed Goldilocks conditions or the Goldilocks principle, which describes how "circumstances must be right for any type of complexity to form or continue to exist," as emphasized by Spier in his recent book.[20] For humans, bodily temperatures can neither be too hot nor too cold; for life to form on a planet, it can neither have too much nor too little energy from sunlight. Stars require sufficient quantities of hydrogen, sufficiently packed together under tremendous gravity, to cause nuclear fusion.[20]

Christian suggests that complexity arises when these Goldilocks conditions are met, that is, when things are not too hot or cold, not too fast or slow. For example, life began not in solids (molecules are stuck together, preventing the right kinds of associations) or gases (molecules move too fast to enable favorable associations) but in liquids such as water that permitted the right kinds of interactions at the right speeds.[51]

Somewhat in contrast, Chaisson has maintained for well more than a decade that "organizational complexity is mostly governed by the optimum use of energy—not too little as to starve a system, yet not too much as to destroy it". Neither maximum energy principles nor minimum entropy states are likely relevant to appreciate the emergence of complexity in Nature writ large.[55]

Other themes[edit source]

Advances in particular sciences such as archaeology, gene mapping, and evolutionary ecology have enabled historians to gain new insights into the early origins of humans, despite the lack of written sources.[2] One account suggested that proponents of Big History were trying to "upend" the conventional practice in historiography of relying on written records.[2]

Big History proponents suggest that humans have been affecting climate change throughout history, by such methods as slash-and-burn agriculture, although past modifications have been on a lesser scale than in recent years during the Industrial Revolution.[2]

A book by Daniel Lord Smail in 2008 suggested that history was a continuing process of humans learning to self-modify our mental states by using stimulants such as coffee and tobacco, as well as other means such as religious rites or romance novels.[18] His view is that culture and biology are highly intertwined, such that cultural practices may cause human brains to be wired differently from those in different societies.[18]

Another theme that has been actively discussed recently by the Big History community is the issue of the Big History Singularity. [56] [57][58][59][60]

Presentation by web-based interactive video[edit source]

Big History is more likely than conventional history to be taught with interactive "video-heavy" websites without textbooks, according to one account.[12] The discipline has benefited from having new ways of presenting themes and concepts in new formats, often supplemented by Internet and computer technology.[1] For example, the ChronoZoom project is a way to explore the 14 billion year history of the universe in an interactive website format.[9][61] It was described in one account:

ChronoZoom splays out the entirety of cosmic history in a web browser, where users can click into different epochs to learn about the events that have culminated to bring us to where we are today—in my case, sitting in an office chair writing about space. Eager to learn about the Stelliferous epoch? Click away, my fellow explorer. Curious about the formation of the earth? Jump into the "Earth and Solar System" section to see historian David Christian talk about the birth of our homeworld.

— TechCrunch, 2012[61]

In 2012, the History channel showed the film History of the World in Two Hours.[1][9] It showed how dinosaurs effectively dominated mammals for 160 million years until an asteroid impact wiped them out.[1] One report suggested the History channel had won a sponsorship from StanChart to develop a Big History program entitled Mankind.[62] In 2013 the History channel's new H2 network debuted the 10-part series Big History, narrated by Bryan Cranston and featuring David Christian and an assortment of historians, scientists and related experts.[63] Each episode centered on a major Big History topic such as salt, mountains, cold, flight, water, meteors and megastructures.

History of the field[edit source]

Early efforts[edit source]

While the emerging field of Big History in its present state is generally seen as having emerged in the past two decades beginning around 1990, there have been numerous precedents going back almost 150 years. In the mid-19th century, Alexander von Humboldt's book Cosmos, and Robert Chambers' 1844 book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation[20] were seen as early precursors to the field.[20] In a sense, Darwin's theory of evolution was, in itself, an attempt to explain a biological phenomenon by examining longer term cause-and-effect processes. In the first half of the 20th century, secular biologist Julian Huxley originated the term "evolutionary humanism",[1] while around the same time the French Jesuit paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin examined links between cosmic evolution and a tendency towards complexification (including human consciousness), while envisaging compatibility between cosmology, evolution, and theology. In the mid and later 20th century, The Ascent of Man by Jacob Bronowski examined history from a multidisciplinary perspective. Later, Eric Chaisson explored the subject of cosmic evolution quantitatively in terms of energy rate density, and the astronomer Carl Sagan wrote Cosmos.[1] Thomas Berry, a cultural historian, and the academic Brian Swimme explored meaning behind myths and encouraged academics to explore themes beyond organized religion.[1]

The field continued to evolve from interdisciplinary studies during the mid-20th century, stimulated in part by the Cold War and the Space Race. Some early efforts were courses in Cosmic Evolution at Harvard University in the United States, and Universal History in the Soviet Union. One account suggested that the notable Earthrise photo, taken by William Anders during a lunar orbit by the Apollo 8, which showed Earth as a small blue and white ball behind a stark and desolate lunar landscape, not only stimulated the environmental movement but also caused an upsurge of interdisciplinary interest.[20] The French historian Fernand Braudel examined daily life with investigations of "large-scale historical forces like geology and climate".[23] Physiologist Jared Diamond in his book Guns, Germs, and Steel examined the interplay between geography and human evolution;[23] for example, he argued that the horizontal shape of the Eurasian continent enabled human civilizations to advance more quickly than the vertical north-south shape of the American continent, because an east-west continental axis and correspondingly similar climates facilitated the transfer and exchange of animals (as protein, for pulling carts, and other uses), ideas and information, as well as structures of human competition that honed and fine-tuned cultural and technological achievements.

In the 1970s, scholars in the United States including geologist Preston Cloud of the University of Minnesota, astronomer G. Siegfried Kutter at Evergreen State College in Washington state, and Harvard University astrophysicists George B. Field and Eric Chaisson started synthesizing knowledge to form a "science-based history of everything", although each of these scholars emphasized somewhat their own particular specializations in their courses and books.[20] In 1980, the Austrian philosopher Erich Jantsch wrote The Self-Organizing Universe which viewed history in terms of what he called "process structures".[20] There was an experimental course taught by John Mears at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, and more formal courses at the university level began to appear.

In 1991 Clive Ponting wrote A Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations. His analysis did not begin with the Big Bang, but his chapter "Foundations of History" explored the influences of large-scale geological and astronomical forces over a broad time period.

Sometimes the terms "Deep History" and "Big History" are interchangeable, but sometimes "Deep History" simply refers to history going back several hundred thousand years or more without the other senses of being a movement within history itself.[64][65]

David Christian[edit source]

One exponent is David Christian of Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.[66][67] He read widely in diverse fields in science, and believed that much was missing from the general study of history. His first university-level course was offered in 1989.[20] He developed a college course beginning with the Big Bang to the present[12] in which he collaborated with numerous colleagues from diverse fields in science and the humanities and the social sciences. This course eventually became a Teaching Company course entitled Big History: The Big Bang, Life on Earth, and the Rise of Humanity, with 24 hours of lectures,[1] which appeared in 2008.[9]

Since the 1990s, other universities began to offer similar courses. In 1994 at the University of Amsterdam and the Eindhoven University of Technology, college courses were offered.[20] In 1996, Fred Spier wrote The Structure of Big History.[20] Spier looked at structured processes which he termed "regimes":

I defined a regime in its most general sense as 'a more or less regular but ultimately unstable pattern that has a certain temporal permanence', a definition which can be applied to human cultures, human and non-human physiology, non-human nature, as well as to organic and inorganic phenomena at all levels of complexity. By defining 'regime' in this way, human cultural regimes thus became a subcategory of regimes in general, and the approach allowed me to look systematically at interactions among different regimes which together produce big history.

— Fred Spier, 2008[20]

Christian's course caught the attention of philanthropist Bill Gates, who discussed with him how to turn Big History into a high school-level course. Gates said about David Christian:

He really blew me away. Here's a guy who's read across the sciences, humanities, and social sciences and brought it together in a single framework. It made me wish that I could have taken big history when I was young, because it would have given me a way to think about all of the school work and reading that followed. In particular, it really put the sciences in an interesting historical context and explained how they apply to a lot of contemporary concerns.

— Bill Gates, in 2012[4]

Educational courses[edit source]

By 2002, a dozen college courses on Big History had sprung up around the world.[23] Cynthia Stokes Brown initiated Big History at the Dominican University of California, and she wrote Big History: From the Big Bang to the Present.[68] In 2010, Dominican University of California launched the world's first Big History program to be required of all first-year students, as part of the school's general education track. This program, directed by Mojgan Behmand, includes a one-semester survey of Big History, and an interdisciplinary second-semester course exploring the Big History metanarrative through the lens of a particular discipline or subject.[9][69] A course description reads:

Welcome to First Year Experience Big History at Dominican University of California. Our program invites you on an immense journey through time, to witness the first moments of our universe, the birth of stars and planets, the formation of life on Earth, the dawn of human consciousness, and the ever-unfolding story of humans as Earth's dominant species. Explore the inevitable question of what it means to be human and our momentous role in shaping possible futures for our planet.

— course description 2012[70]

The Dominican faculty's approach is to synthesize the disparate threads of Big History thought, in order to teach the content, develop critical thinking and writing skills, and prepare students to wrestle with the philosophical implications of the Big History metanarrative. In 2015, University of California Press published Teaching Big History, a comprehensive pedagogical guide for teaching Big History, edited by Richard B. Simon, Mojgan Behmand, and Thomas Burke, and written by the Dominican faculty.[71]

Barry Rodrigue, at the University of Southern Maine, established the first general education course and the first online version, which has drawn students from around the world.[19] The University of Queensland in Australia offers an undergraduate course entitled Global History, required for all history majors, which "surveys how powerful forces and factors at work on large time-scales have shaped human history". By 2011, 50 professors around the world have offered courses. In 2012, one report suggested that Big History was being practiced as a "coherent form of research and teaching" by hundreds of academics from different disciplines.[9]

There are efforts to bring Big History to younger students.[3] In 2008, Christian and his colleagues began developing a course for secondary school students.[20] In 2011, a pilot high school course was taught to 3,000 kids in 50 high schools worldwide.[12] In 2012, there were 87 schools, with 50 in the United States, teaching Big History, with the pilot program set to double in 2013 for students in the ninth and tenth grades,[4] and even in one middle school.[72] The subject is a STEM course at one high school.[73]

There are initiatives to make Big History a required standard course for university students throughout the world. An education project founded by philanthropist Bill Gates from his personal funds was launched in Australia and the United States, to offer a free online version of the course to high school students.[7]

International Big History Association[edit source]

The International Big History Association (IBHA) was founded at the Coldigioco Geological Observatory in Coldigioco, Marche, Italy, on 20 August 2010.[74] Its headquarters is located at Grand Valley State University in Allendale, Michigan, United States. Its inaugural gathering in 2012 was described as "big news" in a report in The Huffington Post.[1]

People involved[edit source]

Some notable academics involved with the concept include:[9]

- David Christian of Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

- Eric Chaisson of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Walter Alvarez of the University of California, Berkeley, California

- Craig Benjamin of Grand Valley State University, Allendale, Michigan

- Cynthia Stokes Brown of Dominican University of California, San Rafael, California

- Andrey Korotayev of the Center for Big History and System Forecasting of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia

- Graeme Snooks of the Australian National University and the Institute of Global Dynamic Systems, Canberra, Australia.[75]

See also[edit source]

References[edit source]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Rev. Michael Dowd (May 8, 2012). "Big History Hits the Big Time". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

"Big History" has entered the big leagues ...

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Patricia Cohen (September 26, 2011). "History That's Written in Beads as Well as in Words". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ursula Goodenough (February 10, 2011). "It's Time for a New Narrative; It's Time for 'Big History'". NPR. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Tom Vander Ark (December 13, 2012). "Big History: An Organizing Principle for a Compelling Class, Block or School". Education Week. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ^ Christian, David (2004). Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. University of California Press.

- ^ Stearns, Peter N. Growing Up: The History of Childhood in a Global Context. p. 9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Vanessa Thorpe (27 October 2012). "Big History theories pose latest challenge to traditional curriculum: Maverick academic's 'Big History' – which is backed by Bill Gates – is subject of new documentary". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

Big History, a movement spearheaded by the Oxford-educated maverick historian David Christian,...

- ^ "International Big History Association". Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Craig Benjamin (July 2012). "Recent Developments in Big History". History of Science Society. 41(3). Archived from the original on 2013-01-09. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ^ "Big History School".

- ^ "Big History Project".

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Stephanie M. McPherson (2012). "5 big ideas that just might transform the classroom: From longer days to history courses that span 13.7 billion years, these notions just might transform the classroom". Boston Globe Magazine. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

1. Tale the Really Long View

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL4e9AQVlcJTQdxGeeApugAEomCc02lchm

- ^ "Big History: Connecting Knowledge".

- ^ Connie Barlow and Michael Dowd (December 13, 2012). "Failing Our Youth: A Call to Religious Liberals". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

Historian David Christian ... "big history."

- ^ Big History Project (16 December 2013). "Introduction to Cosmology" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Cosmic Evolution – More Than Big History by Another Name". www.sociostudies.org.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Alexander Star (book reviewer) Daniel Lord Smail (author of 'On Deep History and the Brain') (March 16, 2008). "I Feel Good". The New York Times Sunday Book Review. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

In "On Deep History and the Brain," Daniel Lord Smail suggests that human history can be understood as a long, unbroken sequence...

- ^ Jump up to:a b "The Collaborative of Global and Big History". University of Southern Maine. 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-12-15. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

Big History is a history of the universe from its origins to the present and beyond....

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Fred Spier (2008). "Big History: The Emergence of an Interdisciplinary Science?". World History Connected. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

'Big history' is a fresh approach to history that places human history within the wider framework of the history of the universe....

- ^ Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 2008, Vol. 33, No. 2, Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining. Published by Maney

- ^ Joseph Manning (March 19, 2011). "Beyond the Pharaohs". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

Remarkable, then, that Egypt has been given short shrift in the current trend for "big history."

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Emily Eakin (January 12, 2002). "For Big History, The Past Begins at the Beginning". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

... historical research has become more and more specialized. ...

- ^ Christian, David. Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. p. 441.

- ^ Stamhuis, Ida H. The Changing Image of the Sciences. p. 146.

- ^ Kannberg, Henry. "Optimism". Scribd. Retrieved 21 June2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Doerr, Anthony (November 18, 2007). "Why the past isn't really past". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

reviews of these books: On Deep History and the Brain – By Daniel Lord Smail...

- ^ "'Big History': the annihilation of human agency". www.spiked-online.com. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ^ Sorkin, Andrew Ross (2014-09-05). "So Bill Gates Has This Idea for a History Class ..." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ^ Baker, D. (2012). "Big History". Times Literary Supplement, (5713), 6.

- ^ Baker, David. "Collective Learning: A Potential Unifying Theme of Human History" Journal of World History (2015) vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 77–104

- ^ John Green (David Baker, scriptwriter) Crash Course Big History: Exploring the Universe https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fi30zjQhtWY

- ^ Palmeri, J., "Bringing Cosmos to Culture: Harlow Shapley and the Uses of Cosmic Evolution," in Cosmos & Culture: Cultural Evolution in a Cosmic Context, Dick, S.J and Lupsella, M.L. (eds.), NASA SP4802, Washington, 2009. ISBN 978-0-16-083119-5

- ^ Sagan, C., Cosmos, Random House, 1980, ISBN 0-394-50294-9

- ^ Chaisson, E., Cosmic Dawn: The Origins of Matter and Life, Atlantic Monthly/Little, Brown, 1981, ISBN 0-316-13590-9

- ^ Reeves, H., Patience dans l'azur: L'evolution cosmique, Éditions du Seuil, 1981

- ^ Jantsch, E., The Self-Organizing Universe, Pergamon, 1980

- ^ Cloud, P., Cosmos, Earth, and Man, Yale Univ. Press, 1980

- ^ Chaisson, E.J., Cosmic Evolution: Rise of Complexity in Nature, Harvard Univ. Press, 2001. ISBN 0-674-00987-8

- ^ Dick, S.J., and Lupsella, M.L., Cosmos & Culture: Cultural Evolution in a Cosmic Context, NASA SP4802, Washington, 2009. ISBN 978-0-16-083119-5

- ^ Dick, S. and Strick, J., The Living Universe, Rutgers University Press, 2004 ISBN 0-8135-3733-9

- ^ Chaisson, E.J.,"Researching and Teaching Cosmic Evolution," in From Big Bang to Global Civilization: A Big History Anthology, Rodriguez, Grinin, Korotayev, (eds.), University of California Press, Berkeley, 2013.

- ^ "Cosmic Evolution – Intro to Movies". www.cfa.harvard.edu.

- ^ Chaisson, E.J.,Cosmic Evolution: Rise of Complexity in Nature, Harvard Univ. Press, 2001. ISBN 0-674-00987-8

- ^ Chaisson, E.J.,"Energy Rate Density as a Complexity Metric and Evolutionary Driver," Complexity, Vol. 16, p. 27, 2011.

- ^ Chaisson, E.J.,"Energy Rate Density. II. Probing Further a New Complexity Metric," Complexity, Vol. 17, p. 44, 2011.

- ^ "The Natural Science Underlying Big History," The Scientific World Journal, v. 2014, 41 pp., 2014; doi:10.1155/2014/384912.

- ^ Chaisson, E.J., "A unifying concept for astrobiology,"International Journal of Astrobiology, Vol. 2, p. 91, 2003.

- ^ Chaisson, E.J., "Using Complexity Science to Search for Unity in the Natural Sciences," in Complexity and the Arrow of Time: What is Complexity?, Lineweaver, Davies and Ruse (eds.), Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013.

- ^ Spier, F., Big History and the Future of Humanity, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j David Christian (March 2011). "David Christian: The history of our world in 18 minutes". TED: Ideas worth spreading. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

(18 minute TED talk)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Christian, David (2008). Big History: The Big Bang, Life on Earth, and the Rise of Humanity. Chantilly, Virginia: The Teaching Company. ISBN 9781598034110.

- ^ "Big History Project: The Future". Big History Project. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "The Future – Big History Project Course". Big History Project. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ Chaisson, E.J., "Complexity: An Energetics Agenda,"Complexity, v. 9, p. 14, 2004.

- ^ Nazaretyan A.P. 2017. Mega-History and the Twenty-First Century Singularity Puzzle.Social Evolution & History 16(1): 31–52.

- ^ Panov A.D. 2017. Singularity of Evolution and Post-Singular Development. From Big Bang to Galactic Civilizations. A Big History Anthology. Volume III. The Ways that Big History Works: Cosmos, Life, Society and our Future. Ed. by B. Rodrigue, L. Grinin, A. Korotayev. Delhi: Primus Books. pp. 370–402.

- ^ Korotayev, Andrey (2018). "The 21st Century Singularity and its Big History Implications: A re-analysis". Journal of Big History. 2 (3): 71–118. doi:10.22339/jbh.v2i3.2320.

- ^ LePoire D. Potential Economic and Energy Indicators of Inflection in Complexity. Evolution 3 (2013): 108–18.

- ^ The 21st Century Singularity and Global Futures. World-Systems Evolution and Global Futures. 2020. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33730-8. ISBN 978-3-030-33729-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b TechCrunch. "Explore 13.7 Billion Years of Cosmic History in Your Browser with ChronoZoom". Boston.com. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

For a bit of perspective, why not take a few minutes this fine Friday afternoon and explore the nearly 14 billion year history of the cosmos as we know it? ...

- ^ "History Channel Lands StanChart Sponsorship". Asia Media Journal. November 15, 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

... Mankind's path is guided by events that stretch back, not hundreds, but thousands, even millions of years...

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (1 November 2013). "'Big History,' a New Series, Debuts on H2". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Benjamin Strauss and Robert Kopp (November 24, 2012). "Rising Seas, Vanishing Coastlines". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ^ Alan Wolfe (September 30, 2011). "The Origins of Religion, Beginning with the Big Bang". The New York Times Sunday Book Review. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ^ Christian was also affiliated with San Diego State Universityin California.

- ^ San Diego State University Archived December 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dominican Professor Examines Big History". Dominican University of California. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ "General Education (GE) Requirements". Dominican University of California. 2011-04-12. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ^ "Expanding Minds in an Expanding Universe". Dominican University of California. 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-01-15. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

Welcome to First Year Experience "Big History" at Dominican University of California. ...

- ^ Simon, Richard B., Mojgan Behmand, and Thomas Burke. Teaching Big History. University of California Press, 2015.

- ^ David Axelson (November 30, 2012). "Coronado School District Explores Online Student Registration". Coronado Eagle & Journal. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

... Never before have science and history been so integrated and in depth. ...

- ^ Carol ladwig (December 3, 2012). "Snoqualmie school's freshman STEM exploratory scrapped for expanded math, science offerings". Snoqualmie Valley Record. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

... a full year of a STEM-based social studies class called "The Big History Project" ...

- ^ "OGC". www.geosc.psu.edu.

- ^ "Institute of Global Dynamic Systems". sites.google.com.

External links[edit source]

- ChronoZoom website

- Teaching & Researching Big History: Exploring a New Scholarly Field, International Big History Association, 2014.

- Cosmic evolution website, a multi-media web site with many video/animation interactive features for both introductory learners and technical experts

- Official website for the International Big History Association

- Big History Site website, multilingual

- Co-evolution in Big History – a transdisciplinary and biomimetic introduction to the Sustainable Development Goals.