William Law

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

This article is about the British theological writer. For other people, see William Law (disambiguation).

William Law

Born 1686

Kings Cliffe, Northamptonshire

Died 9 April 1761

Kings Cliffe, Northamptonshire

Venerated in Anglican Communion

Feast 10 April

William Law (1686 – 9 April 1761) was a Church of England priest who lost his position at Emmanuel College, Cambridge when his conscience would not allow him to take the required oath of allegiance to the first Hanoverian monarch, King George I. Previously William Law had given his allegiance to the House of Stuart and is sometimes considered a second-generation non-juror. Thereafter, Law first continued as a simple priest (curate) and when that too became impossible without the required oath, Law taught privately, as well as wrote extensively. His personal integrity, as well as his mystic and theological writing greatly influenced the evangelical movement of his day as well as Enlightenment thinkers such as the writer Dr Samuel Johnson and the historian Edward Gibbon. In 1784 William Wilberforce (1759–1833), the politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to stop the slave trade, was deeply touched by reading William Law's book A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1729).[1] Law's spiritual writings remain in print today.

Contents

1Early life

2Bangorian controversy and after

3Writings on practical divinity

4Mysticism

4.1Law's Admiration for Isaac Newton and Jakob Böhme

5Veneration

6List of works

7Notes

8References

9External links

Early life[edit]

Law was born at Kings Cliffe, Northamptonshire, in 1686. In 1705 he entered Emmanuel College, Cambridge as a sizar, where he studied the classics, Hebrew, philosophy and mathematics. In 1711 he was elected fellow of his college and was ordained. He resided at Cambridge, teaching and taking occasional duty until the accession of George I, when his conscience forbade him to take the oaths of allegiance to the new government and of abjuration of the Stuarts. His Jacobitism had already been betrayed in a tripos speech. As a non-juror, he was deprived of his fellowship.[2]

For the next few years Law is said to have been a curate in London. By 1727 he lived with Edward Gibbon (1666–1736) at Putney as tutor to his son Edward, father of the historian, who says that Law became the much-honoured friend and spiritual director of the family. In the same year he accompanied his pupil to Cambridge and lived with him as governor, in term time, for the next four years. His pupil then went abroad but Law was left at Putney, where he remained in Gibbon's house for more than 10 years, acting as a religious guide not only to the family but to a number of earnest-minded people who came to consult him. The most eminent of these were the two brothers, John and Charles Wesley, John Byrom the poet, George Cheyne the Newtonian physician, and Archibald Hutcheson, MP for Hastings.[2]

The household dispersed in 1737. Law by 1740 retired to Kings Cliffe, where he had inherited from his father a house and a small property. There he was joined by Elizabeth Hutcheson, the rich widow of his old friend (who recommended on his death-bed that she place herself under Law's spiritual guidance) and Hester Gibbon, sister to his late pupil. For the next 21 years, the trio devoted themselves to worship, study and charity, until Law died on 9 April 1761.[2]

Bangorian controversy and after[edit]

Further information: Bangorian controversy

The first of Law's controversial works was Three Letters to the Bishop of Bangor (1717), a contribution to the Bangorian controversy on the high church side. It was followed by Remarks on Mandeville's Fable of the Bees (1723), in which he vindicated morality; it was praised by John Sterling, and republished by F. D. Maurice. Law's Case of Reason (1732), in answer to Tindal's Christianity as old as the Creation is to some extent an anticipation of Joseph Butler's argument in the Analogy of Religion. His Letters to a Lady inclined to enter the Church of Rome are specimens of the attitude of a High Church Anglican towards Roman Catholicism.[2]

Writings on practical divinity[edit]

A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1729), together with its predecessor, A Practical Treatise Upon Christian Perfection (1726), deeply influenced the chief actors in the great Evangelical revival.[3] John and Charles Wesley, George Whitefield, Henry Venn, Thomas Scott, and Thomas Adam all express their deep obligation to the author. The Serious Call also affected others deeply. Samuel Johnson,[4] Gibbon, Lord Lyttelton and Bishop Home all spoke enthusiastically of its merits; and it is still the work by which its author is popularly known. It has high merits of style, being lucid and pointed to a degree.[2]

In a tract entitled The Absolute Unlawfulness of the Stage Entertainment (1726) Law was agitated by the corruptions of the stage to preach against all plays, and incurred some criticism the same year from John Dennis in The Stage Defended.[2]

His writing is anthologised by various denominations, including in the Classics of Western Spirituality series by the Catholic Paulist Press.

The devotional writer Andrew Murray was so impressed by Law's writings that he republished a number of his works, stating "I do not know where to find anywhere else the same clear and powerful statement of the truth which the Church needs at the present day."[5]

Mysticism[edit]

Böhme's cosmogony: The Philosophical Sphere or the Wonder Eye of Eternity (1620).

In his later years, Law became an admirer of the German Christian mystic Jakob Böhme. The journal of Law's friend John Byrom mentions that, probably around 1735 or 1736, the physician and Behmenist George Cheyne had drawn Law's attention to the book Fides et Ratio, written in 1708 by the French Protestant theologian Pierre Poiret. It was in this book that Law came across the name of the mystic Jakob Böhme.[6][7] From then on Law's writings such as A Demonstration of the Errors of a late Book (1737) and The Grounds and Reasons of Christian Regeneration (1739), began to contain a mystical note.[8] In 1740 appeared An Earnest and Serious Answer to Dr. Trapp and in 1742 An Appeal to All that Doubt. The Appeal was greatly admired by Law's friend George Cheyne, who wrote on 9 March 1742 to his good friend, the printer and novelist Samuel Richardson: "Have you seen Law's Appeal ... it is admirable and unanswerable". John Byrom wrote a poem based on An Earnest and Serious Answer, which was found among the manuscripts of Samuel Richardson after his death in 1761.[9]

Law's mystical tendencies caused the first breach in 1738 between Law and the practical-minded John Wesley after an exchange of four letters in which each explained his own position.[10] After eighteen years of silence Wesley attacked Law and his Behmenist philosophy once again in an open letter in 1756 in which Wesley wrote:

Lime Grove Putney (1846), home of the Gibbon family where William Law walked with John Byrom and other friends.

I have scarce met with a greater friend to darkness except 'the illuminated Jacob Behmen'. But, Sir, have you not done him an irreparable injury? I do not mean by misrepresenting his sentiments; (though some of his profound admirers are positive that you misunderstand and murder him throughout) but by dragging him out of his awful obscurity; by pouring light upon his venerable darkness. Men may admire the deepness of the well, and the excellence of the water it contains: But if some officious person puts a light into it, it will appear to be both very shallow and very dirty. I could not have borne to spend so many words on so egregious trifles, but that they are mischievous trifles: ... bad philosophy has, by insensible degrees, paved the way for bad divinity.[11]

Law never responded to this open letter, though he had been deeply upset, as was testified by John Byrom.[12]

After seven years of silence Law further explored Böhme's ideas in The Spirit of Prayer (1749–1750), followed by The Way to Divine Knowledge (1752) and The Spirit of Love (1752–1754). He worked on a new translation of Böhme's works for which The Way to Divine Knowledge had been the preparation.[13] Samuel Richardson had been involved in the printing of some of Law's works, e.g. A Practical Treatise upon Christian Perfection (second edition of 1728), and The Way to Divine Knowledge (1752), since Law's publishers William and John Innys worked closely with Samuel Richardson.[14]

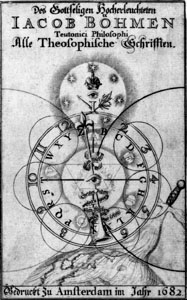

Title page of the Johann Georg Gichtel (1638–1710) edition of 1682, printed in Amsterdam.

Law had taught himself the "High Dutch Language" to be able to read the original text of the "blessed Jacob". He owned a quarto edition of 1715, which had been carefully printed from the Johann Georg Gichtel edition of 1682, printed in Amsterdam where Gichtel (1638–1710) lived and worked.[15]

After the death of both Law and Richardson in 1761, Law's friends George Ward and Thomas Langcake published between 1764 and 1781 a four-volume version of the works of Jakob Böhme. It was paid for by Elizabeth Hutcheson. This version became known as the Law-edition of Böhme, even though Law had never found the time to contribute to this new edition.[16] As a result of this it was ultimately based on the original translations made by John Ellistone and John Sparrow between 1645 and 1662,[17] with only a few changes.[18] This edition was greatly admired by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Blake. Law had found some illustrations made by the German early Böhme exegetist Dionysius Andreas Freher (1649–1728) which had been included in this edition. Upon seeing these symbolic drawings Blake said during a dinner party in 1825 "Michel Angelo could not have surpassed them".[19]

Law's Admiration for Isaac Newton and Jakob Böhme[edit]

Law greatly admired both Isaac Newton, whom he called "this great philosopher" and Jakob Böhme, "the illuminated instrument of God". In part I of The Spirit of Love (1752) Law wrote that in the three properties of desire one can see the "Ground and Reason" of the three great "laws of matter and motion lately discovered [by Sir Isaac Newton]". Law added that he "need[ed] no more to be told that the illustrious Sir Isaac [had] ploughed with Behmen's heifer" which had led to the discovery of these laws.[20]

Law added that in the mathematical system of Newton these three properties of desire, i.e. "attraction, equal resistance, and the orbicular motion of the planets as the effect of them", are treated as facts and appearances, whose ground appears not to be known. However, Law wrote, it is in "our Behmen, the illuminated Instrument of God" that:

Their Birth and Power in Eternity are opened; their eternal Beginning is shown, and how and why all Worlds, and every Life of every Creature, whether it be heavenly, earthly, or hellish, must be in them, and from them, and can have no Nature, either spiritual or material, no kind of Happiness or Misery, but according to the working Power and State of these Properties. All outward Nature, all inward Life, is what it is, and works as it works, from this unceasing powerful Attraction, Resistance, and Whirling."[21]

Aldous Huxley quotes admiringly and at length from Law's writings on mysticism in his anthology The Perennial Philosophy, pointing out remarkable parallels between his ( Law's ) mystical insights and those of Mahayana Buddhism, Vedanta, Sufism, Taoism and other traditions encompassed by Leibniz's concept of the Philosophia Perennis.

Granted that the ground of the individual soul is akin to...the divine Ground of all existence...what is the ultimate nature of good and evil, and what the true purpose and end of life? The answers to these questions will be given to a great extent in the words of that most surprising product of the English eighteenth century, William Law...a man who was not only a master of English prose, but also one of the most interesting thinkers of his period and one of the most endearingly saintly figures in the whole history of Anglicanism.[22]

Veneration[edit]

Law is honoured on 10 April with a feast day on the Calendar of saints, the Calendar of saints (Episcopal Church in the United States of America) and other Anglican churches.

William is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 10 April.[23]

List of works[edit]

- Remarks upon a Late Book, Entituled, The Fable of the Bees (1724)

- "A Practical Treatise Upon Christian Perfection" (1726)

- A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1729)

- A Demonstration of the Gross and Fundamental Errors of a late Book called a Plain Account, etc., of the Lord's Supper (1737)

- The Grounds and Reasons of the Christian Regeneration (1739)

- An Earnest and Serious Answer to Dr Trapp's Sermon on being Righteous Overmuch (1740)

- Appeal to all that Doubt and Disbelieve the Truths of Revelation (1742)

- The Spirit of Prayer (1749, 1750)

- The Way to Divine Knowledge (1752)

- The Spirit of Love (1752-1754)

- A Short but Sufficient Confutation of Dr Warburton's Projected Defence (as he calls it) of Christianity in his Divine Legation of Moses (1757). Reply to The Divine Legation of Moses.

- A Collection of Letters on the Most Interesting and Important Subjects, and on Several Occasions (1760)

- Of Justification by Faith and Works, A Dialogue between a Methodist and a Churchman (1760)

- An Humble, Earnest and Affectionate Address to the Clergy (1761) renamed "The Power of the Spirit" by Andrew Murray in his 1896 reprint.

- You Will Receive Power

- The Way to Christ by Jakob Boehme, translated by William Law

Notes[edit]

^ "BBC - Religions - Christianity: William Wilberforce".

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Chisholm 1911.

^ In A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life Law urges that every day should be viewed as a day of humility by learning to serve others. Foster, Richard J., Celebration Of Discipline, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988, p.131.

^ "I became a sort of lax talker against religion, for I did not think much against it; and this lasted until I went to Oxford, where it would not be suffered. When at Oxford, I took up Law's Serious Call, expecting to find it a dull book (as such books generally are), and perhaps to laugh at it. But I found Law quite an overmatch for me; and this was the first occasion of my thinking in earnest of religion after I became capable of rational inquiry.", Samuel Johnson, recounted in James Boswell's, Life of Johnson, ch. 1.

^ Murray, Andrew (1896). The Power of the Spirit. London: James Nisbet. pp. ix.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 112–113.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2006, pp. 442–465.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 120 ff.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2006, pp. 454–456.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2006, pp. 448–452.

^ J. Wesley, Works, Vol. IX, pp. 477-478.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2006, pp. 460–463.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 138 ff.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 118–120, 138.

^ This edition is the Theosophia Revelata. Das isst: Alle Göttliche Schriften des Gottseligen und hocherleuchteten Deutschen Theosophi Jacob Böhmens, 2 Vols., Johann Otto Glüssing, Hamburg, 1715.

^ This William Law edition is available online, see http://www.jacobboehmeonline.com/william_law.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, p. 144.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, pp. 138–141.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, p. 140.

^ Joling-van der Sar 2003, p. 133.

^ William Law, Works, 9 volumes, (reprint of the Moreton ed., Brockenhurst, Setley, 1892-93 which was a reprint of London edition of 1762), Wipf and Stock Publishers, Eugene, Oregon, U.S.A., 2001, Vol. VIII, pp. 19-20.

^ Huxley, Aldous 'The Perennial Philosophy', first edition pub. Chatto and Windus 1946.

^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

References[edit]

Abby, Charles J., The English Church in the 18th Century, 1887.

Foster, Richard J., Celebration Of Discipline, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988.

Huxley, Aldous, The Perennial Philosophy, 1945.

Joling-van der Sar, Gerda J. (2006). "The controversy between William Law and John Wesley". English Studies. Informa UK Limited. 87 (4): 442–465. doi:10.1080/00138380600757810. ISSN 0013-838X.

Joling-van der Sar, Gerda J. (2003). The spiritual side of Samuel Richardson : mysticism, Behmenism and millenarianism in an eighteenth-century English novelist (Thesis). University of Leiden. ISBN 90-90-17087-1. OCLC 783182681. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

Lecky, W.E.H, History of England in the 18th Century, 1878–90.

Overton, John Henry, William Law, Nonjuror and Mystic, 1881.

Stephen, Leslie, English Thought in the 18th century.

Stephen, Leslie (1892). "Law, William" . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 32. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Tighe, Richard, A Short Account of the Life and Writings of the Late Rev. William Law, 1813.

Walker, A.Keith. William Law: His Life and Work SPCK, 1973.

Walton, Christopher, Notes and Materials for a Complete Biography of W Law, 1848.

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Law, William". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Law, William". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.External links[edit]

Quotations related to William Law at Wikiquote

Quotations related to William Law at WikiquoteThe Life and Works of William Law - all 17 known works.

Works by or about William Law at Internet Archive

Works by William Law at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Works by William Law at Open Library

William Law Page with the William Law Edition of Jakob Böhme

The Mystical Writings of William Law webpage

[1]