Shingon Buddhism

Jump to:navigation, search

Previous (Shinbutsu shugo)

Next (Shinran)

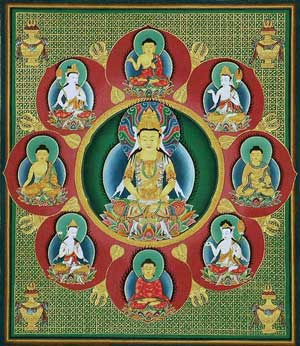

A Japanese mandala of the Five Dhyani Buddhas.

Shingon Buddhism (眞言, 真言 "true words") is a major school of Japanese Buddhism, and is the other branch, besides Tibetan Buddhism, of Vajrayana Buddhism which spread in the eighth century from northeastern and northwestern India to Tibet and Java as well as to China and from there to Japan. It is often called "Japanese Esoteric Buddhism." The word shingon is the Japanese reading of the kanji for the Chinese word zhen yan, literally meaning "true words," which in turn is the Chinese translation of the Sanskrit word mantra. The Shingon school was founded by the Japanese monk Kūkai (774–835; posthumously Kōbō-Daishi) who went to China in 804 and studied tantric practices in the city of Xian, then came back to Japan and developed a modified system. In 819, he established a monastery, Kongōbuji' (金剛峰寺) on Mount Koya south of Kyoto, which became the head of the Shingon sect of Buddhism. Shingon enjoyed immense popularity during the Heian Period (794–1185), particularly among the Heian nobility, and contributed significantly to the art and literature of the time. It also provided a theoretical basis for Buddhist acceptance of Ryobu (“Two Aspects”) Shinto, a Shinto-Buddhist amalgamation, and contributed to the modernization of Buddhism in Japan.

Contents

2 Teachings

3 Mahavairocana Tathagata

4 Practices and features

5 The ten stages of the development of mind

6 Branches of Shingon

7 Mt. Koya

8 See also

9 Notes

10 References

11 External links

12 Credits

The teachings of Shingon are based on esoteric Vajrayana texts, the Mahavairocana Sutra and the Vajrasekhara Sutra (Diamond Crown Sutra). According to Shingon, enlightenment is not a distant, foreign reality that can take eons to approach but a real possibility within this very life, based on the spiritual potential of every living being, known generally as Buddha-nature. If cultivated, this luminous nature manifests as innate wisdom. With the help of a genuine teacher and through properly training the body, speech, and mind, people can reclaim and liberate this enlightened capacity for the benefit of themselves and others.

History

Kongobuji Temple

Shingon Buddhism arose during Japan's Heian period (794-1185). The monk Kūkai (774–835; posthumously Kōbō-Daishi) went to China in 804 and studied tantric practices in the city of Xian, returning to Japan in 806 with many texts and art works. In time, he developed his own synthesis of esoteric practice and doctrine, centered on the universal Buddha Vairocana (or, more accurately, Mahavairocana Tathagata). In 819, he established a monastery, Kongōbuji' (金剛峰寺) on Mount Koya south of Kyoto, which became the head of the Shingon sect of Buddhism. In 823, Kūkai by order of Emperor Saga, was put in charge of Tō-ji temple in Kyoto and made it the headquarters of his sect. In 824, Kūkai was appointed to the administrative body that oversaw all the Buddhist monasteries in Japan, the Soogoo, or Office of Priestly Affairs. In 828, Kūkai opened his School of Arts and Sciences, Shugei shuchi-in, a private institution which was open to all regardless of social rank.

Shingon enjoyed immense popularity during the Heian Period (794–1185), particularly among the Heian nobility, and contributed significantly to the art and literature of the time, as well as influencing other communities, such as the Tendai sect on Mt. Hiei.[1] Shingon's emphasis on ritual appealed to the Kyoto nobility, and found considerable support, particularly from the Fujiwara clan. Shingon was allotted several politically powerful temples in the capital, where rituals for the imperial family and nation were regularly performed. Many of these temples such as Toji, Ninnaji, and Daigoji to the south of Kyoto became ritual centers establishing their own particular ritual lineages.

Schism

Like the Tendai School that branched into the Jōdo, Zen and Nichiren Schools in the Kamakura period, Shingon divided into two major branches; Kogi Shingon, or "old Shingon," and Shingi Shingon, or "New Shingon." This division primarily arose out of a political dispute between Kakuban (覚鑁) and his faction of priests centered at Denbōe (Daidenpoin, 大伝法院) and the leadership at Kongōbuji, the head temple of Mt. Kōya.

Negoro-ji

Kakuban, or Kogyo-Daishi (興教大師) (1095-1143), or Kakuban (覚鑁), was widely renowned as a reformer of the Shingon sect. of Buddhism in Japan. Kakuban, who was originally ordained at Ninnaji in Kyoto, studied at several temple-centers (including the Tendai temple complex at Onjiyōji) before going to Mt. Kōya to pursue Shingon Buddhism. He perceived the corruption that had undermined the Shingon sect during the 300 years since its founding, and set about to revive its original spirit and teaching. He gathered an increasing throng of followers, and through his connections with high-ranking nobles in Kyoto, he was appointed abbot of Mt. Kōya and became the chief priest of both the Daidenpoin (大伝法院) and Kongobuji (金剛峰寺) temples. The leadership at Kongōbuji, however, opposed the appointment on the premise that Kakuban had not originally been ordained on Mt. Kōya. In 1140, the priests of Kongobuji attacked his residence in Kongobuji. After several conflicts Kakuban and his faction of priests left the mountain for Mt. Negoro to the northwest, where they constructed a new temple complex, now known as Negoroji( 根来寺).

After the death of Kakuban in 1143, the Negoro faction returned to Mt. Kōya. However in 1288, the conflict between Kongōbuji and Denbōe (Daidenpoin, 大伝法院) came to a head once again. Led by Raiyu (頼瑜), the Denbōe priests once again left Mt. Kōya, this time establishing their headquarters on Mt. Negoro. This exodus marked the beginning of the Shingi Shingon School at Mt. Negoro, which was the center of Shingi Shingon until sacked by Hideyoshi Toyotomi in 1585.

During the initial stages of his predication in Japan in 1549, the Catholic missionary Francis Xavier was welcomed by the Shingon monks since he used the word Dainichi for the Christian God. As Xavier learned more about the religious nuances of the word, he changed to Deusu from the Latin and Portuguese Deus. The monks also realized by that point that Xavier was preaching a rival religion.

Teachings

The teachings of Shingon are based on esoteric Vajrayana texts, the Mahavairocana Sutra and the Vajrasekhara Sutra (Diamond Crown Sutra). These two mystical teachings are shown in the main two mandalas of Shingon, namely, the Womb Realm (Taizokai) mandala and the Diamond Realm (Kongo Kai) mandala. Vajrayana Buddhism is concerned with the ritual and meditative practices leading to enlightenment. According to Shingon, enlightenment is not a distant, foreign reality that can take aeons to approach but a real possibility within this very life, based on the spiritual potential of every living being, known generally as Buddha-nature. If cultivated, this luminous nature manifests as innate wisdom. With the help of a genuine teacher and through properly training the body, speech, and mind, people can reclaim and liberate this enlightened capacity for the benefit of themselves and others.

Kūkai systematized and categorized the teachings he inherited into ten stages or levels of spiritual realization. He wrote at length on the difference between exoteric (both mainstream Buddhism and Mahayana) and esoteric (Vajrayana) Buddhism. The differences between exoteric and esoteric can be summarised as:Esoteric teachings are preached by the Dharmakaya Buddha (hosshin seppo) which Kūkai identifies with Mahavairocana. Exoteric teachings are preached by the Nirmanakaya Buddha, also known as Gautama Buddha, or one of the Sambhoghakaya Buddhas.

Exoteric Buddhism holds that the ultimate state of Buddhahood is ineffable, and that nothing can be said of it. Esoteric Buddhism holds that while nothing can be said of it verbally, it is readily communicated via esoteric rituals which involve the use of mantras, mudras, and mandalas.

Kūkai held that exoteric doctrines are merely provisional, a skillful means (upaya) on the part of the Buddhas to help beings according to their capacity to understand the Truth. The esoteric doctrines by comparison are the Truth itself, and are a direct communication of the "inner experience of the Dharmakaya's enlightenment."

Some exoteric schools in late Nara and early Heian Japan believed (or were portrayed by Shingon adherents as believing) that attaining Buddhahood is possible but requires three incalculable eons of time and practice to achieve. Esoteric Buddhism teaches that Buddhahood can be attained in this lifetime by anyone.

Kūkai held, along with the Huayan (Japanese Kegon) school that all phenomena could be expressed as "letters" in a "World-text." Mantra, mudra, and mandala constitute the "language" through which the Dharmakaya (Reality itself) communicates. Although portrayed through the use of anthropomorphic metaphors, Shingon does not regard the Dharmakaya Buddha as a god, or creator. The Dharmakaya Buddha is a symbol for the true nature of things which is impermanent and empty of any essence. The teachings were passed from Mahavairocana.

The truth described in the sutras is expressed in natural phenomena such as mountains and oceans, and even in humans. The universe itself embodies and can not be separated from the teaching.[2]According to the Shingon tradition, all things in this universe including physical matter, mind and mental states, are made up of six primary elements: earth (the principle of solidity), water (moisture), fire (energy), wind (movement), space (the state of being unobstructed), and consciousness (the six ways of knowing objects). Buddha is made up of these same six elements, and in this sense Buddha and human beings are essentially identical. When this truth is realized, actions, words, and thoughts will be correct and the living, physical person will achieve Buddhahood.

Mahavairocana Tathagata

In Shingon, Mahavairocana Tathagata is the universal or primordial Buddha that is the basis of all phenomena, present in each and all of them, and not existing independently or externally to them. The goal of Shingon is the realization that one's nature is identical with Mahavairocana, a goal that is achieved through initiation (for ordained followers), meditation, and esoteric ritual practices. This realization depends on receiving the secret doctrine of Shingon, transmitted orally to initiates by the school's masters. Body, speech, and mind participate simultaneously in the subsequent process of revealing one's nature: The body through devotional gestures (mudra) and the use of ritual instruments, speech through sacred formulas (mantra), and mind through meditation.

Shingon places special emphasis on the Thirteen Buddhas[3], a grouping of various Buddhas and boddhisattvas:Acala Vidyaraja (Fudō-Myōō)

Akasagarbha Bodhisattva

Akshobhya Buddha (Ashuku Nyorai)

Amitabha Buddha (Amida Nyorai)

Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva (Kannon)

Bhaisajyaguru Buddha (Yakushirurikō Nyorai)

Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva (Jizo)

Mahasthamaprapta Bodhisattva (Seishi)

Manjusri Bodhisattva (Monju)

Maitreya Bodhisattva (Miroku)

Samantabhadra Bodhisattva (Fugen)

Shakyamuni Buddha (Shaka Nyorai)

Mahavairocana is the Universal Principle which underlies all Buddhist teachings, according to Shingon Buddhism, so other Buddhist figures can be thought of as manifestations with certain roles and attributes. Each Buddhist figure is symbolized by its own Sanskrit "seed" letter as well.

Practices and features

A typical Shingon shrine.

A feature that Shingon shares in common with the other surviving school of Esoteric Buddhism (Tendai) is the use of seed-syllables or bija (bīja) along with anthropomorphic and symbolic representations, to express Buddhist deities in their mandalas. There are four types of mandalas: Mahā-maṇḍala (大曼荼羅, anthropomorphic representation); the seed-syllable mandala or dharma-maṇḍala (法曼荼羅); the samaya-maṇḍala (三昧耶曼荼羅, representations of the vows of the deities in the form of articles they hold or their mudras); and the karma-maṇḍala (羯磨曼荼羅 ) representing the activities of the deities in the three-dimensional form of statues. An ancient Indian Sanskrit syllabary script known as siddham (Jap. shittan 悉曇 or bonji 梵字) is used to write mantras. A core meditative practice of Shingon is ajikan (阿字觀), "Meditating on the Letter 'A'," which uses the siddham letter representing the sound “a.” Other Shingon meditations are Gachirinkan (月輪觀, "full moon" visualization), Gojigonjingan (五字嚴身觀, "visualization of the five elements arrayed in the body" from the Mahāvairocanābhisaṃbodhi-sūtra) and Gosōjōjingan (五相成身觀, pañcābhisaṃbodhi "series of five meditations to attain Buddhahood" from the Sarvatathāgatatattvasaṃgraha).

The essence of Shingon Mantrayana practice is to experience Reality by emulating the inner realization of the Dharmakaya through the meditative ritual use of mantra, mudra and visualization of mandala (the three mysteries). These practices are regarded as gateways to understanding the nature of Reality. All Shingon followers gradually develop a teacher-student relationship with a mentor, who learns the disposition of the student and teaches practices accordingly. For lay practitioners, there is no initiation ceremony beyond the Kechien Kanjō (結縁潅頂), which is normally offered only at Mt. Koya, but is not required. In the case of disciples wishing to be ordained as priests, the process is more complex and requires initiations in various mandalas, rituals and esoteric practices.

Esoteric Buddhism is also practiced, in the Japanese Tendai School founded at around the same time as the Shingon School in the early 9th century (Heian period). The term used there is Mikkyo.

The ten stages of the development of mind

Kūkai wrote his greatest work, The Ten Stages of the Development of Mind, in 830, followed by a simplified summary, The Precious Key to the Secret Treasury, soon afterward. In these books, he explained the ten stages of the mind of a Buddhist monk engaged in ascetic practices. The first stage is a mind which acts on instinct like a ram. The second stage is a mind that starts to think others, and to make offerings. The third stage is the mind of child or a calf that follows its mother. The fourth stage is a mind that can recognize physical and spiritual being, but still denies its own spiritual self. The fifth stage is a mind that recognizes the infinity of all things, eliminates ignorance and longs for Nirvana. The sixth stage is a mind that wants to take away peoples’ suffering and give them joy. The seventh stage is a mind that is the negation of all passing, coming and going, that meditates only on vanity and the void. The eighth stage is a mind that recognizes that all things are pure, the object and subject of the recognition were harmonized. The ninth stage is a mind that, like water, has no fixed boundaries, and is only rippled on the surface by a breeze. Similarly, the world of enlightenment has also no clear edge. The tenth stage is the state of realizing the height of the void (sunya, empty) and the Buddhahood; spiritual enlightenment. Kukai used this theory to rank all the major Buddhist schools, Hinduism, Confucianism, and Taoism according to what he considered their degree of insight. The first through the third stages signify the level of people in general. The fourth and fifth stages represent Hinayana (Theravada, lesser Vehicle) Buddhists. The fourth stage is that of enlightenment through learning Buddha’s words, Zraavaka. The fifth stage is that of self-enlightenment, Pratyekabuddha. The sixth stage indicates the Dharma-character school (Chinese: 法相宗) or Consciousness-only school (Chinese 唯識). The seventh stage represents Sanlun (Traditional Chinese: 三論) or, literally, the Three Treatise School, a Chinese school of Buddhism based upon the Indian Madhyamaka tradition, founded by Nagarjuna. The eighth stage represented Tendai (Japanese: 天台宗, a Japanese school of Mahayana Buddhism) descended from the Chinese Tiantai or Lotus Sutra School. The ninth stage represents Kegon (華厳) a name for the Japanese version of the Huayan School of Chinese Buddhism, brought to Japan via the Korean Hwaeom tradition. The tenth stage represents Shingon (真言). The Shingon school provided the theoretical basis for Buddhist acceptance of Ryobu (“Two Aspects”) Shinto, a Shinto-Buddhist amalgamation.

Branches of Shingon

Located in Kyoto, Japan, Daigo-ji is the head temple of the Daigo-ha branch of Shingon Buddhism.Kōyasan (高野山)

Chisan-ha (智山派)

Buzan-ha (豊山派)

Daikakuji-ha (大覚寺派)

Daigo-ha (醍醐派)

Shingi

Zentsuji-ha

Omuro-ha

Yamashina-ha

Sennyūji-ha

Sumadera-ha

Kokubunji-ha

Sanbōshū

Nakayadera-ha

Shigisan

Inunaki-ha

Tōji

Mt. Koya

Konpon Daitō, the central point of Mt. Koya

Mount Kōya (高野山 Kōya-san), in Wakayama prefecture to the south of Osaka, is the headquarters of the Shingon school, which comprises over 4,000 temples in Japan. Located in an 800-meter-high valley amid the eight peaks of the mountain, the original monastery has grown into the town of Koya, featuring a university dedicated to religious studies, three schools for monks and nuns, a monastery high school and 120 temples, many of which offer lodging to pilgrims.

For more than 1,000 years, women were prohibited from entering Koyasan. A monastery for women was established in Kudoyana, at the foot of Mt. Koya. The prohibition was lifted in 1872.

The mountain is home to the following famous sites:Okunoin (奥の院), the mausoleum of Kūkai, surrounded by an immense graveyard (the largest in Japan)

Konpon Daitō (根本大塔), a pagoda that according to Shingon doctrine represents the central point of a mandala covering not only Mt. Koya but all of Japan

Kongōbu-ji (金剛峰寺), the headquarters of the Shingon sect

In 2004, UNESCO designated Mt. Koya, along with two other locations on the Kii Peninsula, as World Heritage Sites.

Kongobuji Temple

Banryutei rock garden, Kongobuji Temple

Shingon Buddhist monks, Mt. Koya, 2004

Lantern hall near Okunoin

Graves in Okunoin Cemetery

A statue in Okunoin Cemetery

Tokugawa Mausoleum

See alsoKukai

Buddhism in Japan

Notes

↑ R. H. P. Mason and J. G. Caiger, A History of Japan (New York: Free Press, 1974), 106-107.

↑ Koyasan.org, Shingon Teaching. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

↑ Shingon, Jusan Butsu—The Thirteen Buddhas of the Shingon School. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral feesAbé, Ryuichi. The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. 2000. ISBN 0231112866.

Dleitlein, Eijō. Sacred Treasures of Mount Koya: The Art of Japanese Shingon Buddhism. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 2002. ISBN 9780824828028.

Giebel, Rolf W. 2001. Two Esoteric Sutras. BDK English Tripiṭaka, 29-II, 30-II. Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 188643915X.

Kūkai, and Yoshito S. Hakeda. 1972. Kūkai: Major Works. UNESCO collection of representative works: Japanese series. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231036272.

Mason, R. H. P. and J. G. Caiger. A History of Japan. New York: Free Press. 1974

Payne, Richard Karl. 1991. The Tantric Ritual of Japan: Feeding the Gods, the Shingon Fire Ritual. Śata-piṭaka series, v. 365. Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 9788185179766.

Shaner, David Edward. 1985. The Bodymind Experience in Japanese Buddhism: A Phenomenological Perspective of Kūkai and Dōgen. SUNY series in Buddhist studies. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0887060617.

Skilton, Andrew. 1994. A Concise History of Buddhism. Birmingham: Windhorse Publications. ISBN 0904766667.

Unno, Mark. 2004. Shingon Refractions: Myōe and the Mantra of light. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0861713907.

External links

All links retrieved November 3, 2019.The International Shingon Institute

Mandala Society in Croatia

Mandala Vermont, US

Naritasan Shinshoji Temple, Japan

Buddhism topics

History

Timeline · Gautama Buddha · Buddhist councils · History of Buddhism in India · Decline of Buddhism in India · Ashoka the Great · Greco-Buddhism · Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

Foundations

Three Jewels: (Buddha, Dharma, Sangha) · Four Noble Truths · Noble Eightfold Path · Nirvana · Middle Way

Key Concepts

Three Marks of Existence: (Impermanence, Suffering, Not-self) · Dependent Origination · Five Aggregates · Karma · Vipaka · Rebirth · Samsara · Defilements · Five Hindrances · Ten Fetters · Enlightenment Qualities · Perfections · Jhāna · Sense Bases · Four Great Elements · Renunciation · Bodhi · Parinirvana · Two truths doctrine · Emptiness · Bodhicitta · Bodhisattva · Buddha-nature · Bhumi · Trikaya

Cosmology

Ten spiritual realms · Six Realms (Hell, Animal realm, Hungry Ghost realm, Asura realm, Human realm, Heaven) · Three Spheres

Practices

Threefold Training: (Morality, Concentration, Wisdom) · Buddhist devotion · Taking refuge · Four Divine Abidings: (Loving-kindness, Compassion, Sympathetic joy, Equanimity) · Mindfulness · Merit · Puja: (Offerings, Prostration, Chanting) · Paritta · Generosity · Morality: (Five Precepts, Eight Precepts, Ten Precepts, Bodhisattva vows, Patimokkha) · Bhavana · Meditation: (Kammaṭṭhāna, Recollection, Mindfulness of Breathing, Serenity meditation, Insight meditation, Shikantaza, Zazen, Kōan, Mandala, Tonglen, Tantra)

Attainment

Buddhahood · Paccekabuddha · Bodhisattva · Four stages of enlightenment: (Stream-enterer, Once-returner, Non-returner, Arahant) · Monasticism: (Monk, Nun, Novice monk, Novice nun) · Anagarika · Ajahn · Sayadaw · Zen master · Roshi · Lama · Rinpoche · Geshe · Tulku · Householder · Lay follower · Disciple · Ngagpa

Texts

Tipitaka (Vinaya Pitaka, Sutta Pitaka, Abhidhamma Pitaka), Commentaries · Mahayana sutras · Chinese Buddhist canon (Tripitaka Koreana) · Tibetan Buddhist canon

Major Figures

Gautama Buddha · Sāriputta · Mahamoggallāna · Ananda · Maha Kassapa · Buddhaghosa · Nagasena · Bodhidharma · Nagarjuna · Asanga · Padmasambhava · Dalai Lama

Branches

Theravada · Mahayana: (Chan/Zen, Pure Land, Tendai, Nichiren, Madhyamaka, Yogacara) · Vajrayana: (Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon) · Early Buddhist schools · Pre-sectarian Buddhism · Basic points unifying Theravada and Mahayana

Countries

Bhutan · Burma · Cambodia · China · India · Indonesia · Japan · Korea · Laos · Malaysia · Mongolia · Nepal · Russia · Singapore · Sri Lanka · Thailand · Tibet · Vietnam · Western countries

Comparative Buddhism

Science · Psychology · Hinduism · Jainism · East Asian religions · Christianity · Theosophy · Gnosticism

Lists

Buddhists · Buddhas · Twenty-eight Buddhas · Bodhisattvas · Temples · Books · Buddhism-related topics · Terms and concepts

Miscellaneous topics

Tathāgata · Maitreya · Avalokiteśvara (Guan Yin) · Amitābha · Brahmā · Māra · Dhammapada · Visuddhimagga · Vinaya · Sutra · Abhidharma · Buddhist philosophy · Eschatology · Reality in Buddhism · God in Buddhism · Liturgical languages: (Pali, Sanskrit) · Dharma talk · Buddhist calendar · Kalpa · Buddhism and evolution · Buddhism and homosexuality · Fourteen unanswerable questions · Ethics · Culture · Monastic robe · Cuisine · Vegetarianism · Art · Greco-Buddhist art · Buddha statue · Budai · Symbolism · Dharmacakra · Flag · Bhavacakra · Mantra · Om mani padme hum · Prayer wheel · Mala · Mudra · Holidays · Vesak · Uposatha · Vassa · Architecture: (Vihara, Wat, Stupa, Pagoda) · Pilgrimage: (Lumbini, Bodh Gaya, Sarnath, Kushinagar) · Bodhi tree · Mahabodhi Temple · Higher Knowledge · Supernormal Powers · Miracles of the Buddha · Physical characteristics of the Buddha · Family of the Buddha