슈테판 츠바이크

Stefan Zweig | |

|---|---|

| |

| 작가 정보 | |

| 출생 | 1881년 11월 28일 |

| 사망 | 1942년 2월 22일(60세) |

| 국적 | |

| 직업 | 소설가, 저널리스트, 극작가, 전기작가 |

| 학력 | |

| 활동기간 | 1900년대 ~ 1940년대 |

| 부모 | 아버지 모리츠 츠바이크 어머니 이다 브레타우어 |

| 배우자 | 로테 알트만 |

서명 | |

슈테판 츠바이크(독일어: Stefan Zweig, 1881년 11월 28일 ~ 1942년 2월 22일)는 오스트리아의 소설가·저널리스트·극작가·전기작가이다. 빈에서 태어났으며[1], 나치가 정권을 잡자 브라질로 망명하였다가, 마지막 작품인 《발자크》를 미처 완성하지 못한 채 페트로폴리스에서 젊은 아내와 함께 자살하였다.

형식적 완성미가 풍부하고, 프로이트의 심리학을 응용하여 쓴 우수한 단편 소설들이 많다. 유럽 문화의 전통을 유지하려고 노력하였고, 대표작으로 《감정의 혼란》(1926),《광기와 우연의 역사》(1927-1941)가 있다.

생애

슈테판 츠바이크는 오스트리아의 부유한 직물 공장 대표인 아버지 모리츠 츠바이크와 유대계 은행가 가문 출신인 어머니 이다 브레타우어 사이에서 태어났다.

20세에 시집 《은(銀)의 현(絃)》(1901)을 통하여 등단하였고,

빈 대학교에서 철학을 공부하여 1904년 23세 되던 해 「이폴리트 테느의 철학」이라는 논문으로 박사학위를 취득하였다.

그의 학업에 있어서 종교적 요소는 그다지 큰 영향을 미치지 않았지만, 그의 소설 《책벌레 멘델》에서 유대인과 유대교에 대한 내용을 포함하는 등 자신의 유대교적 신념을 포기하지는 않았다. 비록 그의 수필 작품들이 시오니즘을 선도하는 테오도어 헤르츨이 운영하는 《신 자유신문》(Neue Freie Presse)에 실리기는 하였지만, 츠바이크는 헤르츨의 유대적 민족주의(시오니즘)에 동조하지는 않았다.

또한 슈테판 츠바이크는 체코의 작가 에곤 호스토프스키와 친했다. 호스토프스키는 츠바이크와의 관계를 ‘먼 친척되는 사이’라고 묘사하곤 했는데[2], 몇몇 매체는 그들의 사이를 사촌이라고 표현하였다.

제1차 세계대전이 시작되고, 애국주의적 정서가 확대되었는데, 이때 츠바이크뿐만 아니라 마르틴 부버, 헤르만 코엔과 같은 독일인과 오스트리아계 유대인들도 지지의 의사를 내비쳤고, 이러한 정서는 더욱 널리 퍼져나갔다.[3]. 츠바이크는 비록 이에 동조하기는 하였지만, 전쟁에 직접 참여하는 것은 거부하였고, 대신 국방부 기록 보관소에서 근무하였다.

하지만 곧 그는 1915년 노벨 문학상 수상자인 그의 친구 로맹 롤랑과 함께 평화주의를 접하게 되었고, 그 이후로 츠바이크는 인생 전반에 걸쳐서 평화주의를 주장하며 유럽의 통합을 지지했다. 이후 롤랑처럼 츠바이크 또한 수많은 전기문을 썼는데, 《에라스무스 평전》이 대표작이다.

1934년 츠바이크는 아돌프 히틀러의 독일이 힘을 떨치자 이를 피해 아내 프리데리케와 함께 오스트리아를 떠나 런던으로 피신하였다. 1940년 나치 군대가 프랑스를 거쳐 서유럽으로 빠르게 진군하자 츠바이크 부부는 대서양을 건너 미국 뉴욕으로 옮겼고, 같은 해 8월 20일 다시 브라질 리우데자네이루의 위성 도시인 페트로폴리스로 옮겼다[4]. 편협한 사고와 권위주의 그리고 나치즘에 의해 그의 우울증은 깊어져만 갔고, 인류와 미래에 대한 희망이 사라져감을 느낀 츠바이크는 그의 자포자기적인 심정을 노트에 적었다. 결국 츠바이크 부부는 1942년 2월 23일 수면제 과다 복용으로 그들의 집에서 손을 잡고 죽은 채 발견되었다[5][6].

작품 경향

슈테판 츠바이크는 1920년대와 1930년대 최고 유명 작가였다. 또한 아르투어 슈니츨러, 지그문트 프로이트의 친구이기도 했다[7]. 그는 특히 미국, 남미 그리고 유럽 대륙에서 유명했다. 하지만 영국 출판계에서는 무시당했는데[8], 이는 곧 미주에서의 명성이 하락하는 결과로 나타나기도 하였다. 그러나 1990년대 이후부터 미국의 몇몇 유명 출판사에서 그의 작품들을 영어로 번역하여 출판하기 시작했다[9].

그의 작품에 대한 비평은 극과 극으로 나뉘는데, 혹자는 그의 문체가 가볍고, 피상적이라면서 부정적 평가를 내리기도 하며, 혹자는 그의 휴머니즘과 간결하지만 설득력 있는 문체가 유럽의 전통에 더욱 더 매료되게 한다며 긍정적 평가를 내리기도 한다.

츠바이크의 유명 작품으로 중편 소설인 《체스》(1922), 《아모크》(1922), 《모르는 여인으로부터의 편지》(1922)와 소설인 《감정의 혼란》(1926), 《연민》(1939)

그리고 전기문인《조제프 푸셰: 어느 정치적 인간의 초상》(1929),《다른 의견을 가질 권리》(1936) 《에라무스 평전》(1934), 《메리 스튜어트》(1935), 《바다의 정복자: 마젤란 이야기》(1938)가 있다. 츠바이크의 작품이 인기를 끌자 영미권에서는 슈테판 츠바이크를 영어로 그대로 번역한 스티븐 브랜치(Stephen Branch)라는 이름으로 단편집의 해적판이 출간되기도 하였다. 그의 작품 《마리 앙투아네트 베르사유의 장미》(1932)는 1938년 헐리우드 영화로 제작되었다.

츠바이크는 음악가 리하르트 슈트라우스와 함께 있는 것을 좋아했는데, 슈트라우스에게 오페라 《말없는 여자》(Die schweigsame Frau)의 대본을 제공하기도 했다. 슈트라우스는 1935년 6월 24일 드레스덴에서 자신의 첫 작품을 선보일 때, 프로그램에서 츠바이크의 이름을 삭제하라는 나치 정권의 요구에 반항한 것으로 유명한데[10], 그 결과 원래 오페라에 참석하기로 했던 요제프 괴벨스가 오지 않았고 이후 공연 또한 상영 금지 처분을 받아야했다. 1937년 츠바이크는 요제프 그레고르와 오페라 《대프니》(Daphne)의 대본을 공동 제작하여 슈트라우스에게 제공하기도 하였다.

잘츠부르크 완결판 프로젝트

츠바이크의 몇몇 작품은 명성에 비하면 문헌학적 고증이 부실하다는 평가를 받아왔다. 작가가 사망한 후 유럽과 신대륙에서 찾아낸 원고를 스웨덴에서 망명 중인 피셔 출판사에서 펴냈으니 철저한 검증이 이루어질 수가 없었다. 예를 들어 한 작품을 적은 2-3개의 원고가 서로 다소의 차이를 보이는 경우, 어느 것이 작가의 최종 의도를 반영하는지 밝혀내야 하는데 피셔 출판사의 판본은 이 과제를 제대로 해내지 못했다. 전후 츠바이크 저작의 판권을 소유한 피셔 출판사에서 기존 판본들을 오랫동안 계속 펴내면서 미결의 과제는 영원히 남는 듯했다. 그런데 츠바이크의 저작권이 소멸하는 2013년 무렵 잘츠부르크에 위치한 ’슈테판 츠바이크 센터‘와 잘츠부르크 대학교 독문학부는 야심 찬 프로젝트를 함께 시작했다. 츠바이크의 단편 및 장편 소설 일체를 최초로 철저한 문헌학적 고증을 거쳐서 작가의 최후 의도에 따른 완결판 전집 7권으로 내려고 한 것이다. 그 첫 번째 성과가 바로 2017년 발간된 잘츠부르크 전집 제1권 [광기와 우연의 역사]이며 2020년 현재 단편들을 수록한 제2, 제3권이 발간되었다.[11]

기타

한국어 번역 작품

- 《감정의 혼란- 지성을 향한 열망, 제어되지 않는 사랑의 감정》서정일(옮긴이), 녹색광선, 2019년 원제 : Verwirrung der Gefühle (1926), ISBN 979-11-965548-1-1 Confusion of emotions

- 《아메리고- 역사적 오류에 얽힌 이야기 혹은 우리 가슴속에 묻어둔 희망을 두드리는 이야기》, 김재혁 (옮긴이), 삼우반, 2004년, 원제: Amerigo, ISBN 978-89-90745-09-5

- 《위로하는 정신- 체념과 물러섬의 대가 몽테뉴》, 안인희(옮긴이), 유유, 2012년, 원제: Montaigne(1960년), ISBN 978-89-967766-3-5

- 《마리 앙투아네트 베르사유의 장미》, 박광자 & 전영애(옮긴이), 청미래, 2005년, 원제: Marie Antoinette(1932년), ISBN 978-89-86836-21-9

- 《광기와 우연의 역사》, 안인희(옮긴이), 휴머니스트, 2004년, 원제: Sternstunden der Menschheit, ISBN 978-89-89899-91-4 Great moments of humanity

- 《폭력에 대항한 양심》, 안인희(옮긴이), 자작나무, 1998년, ISBN 978-89-76766-27-4

- 《어제의 세계》, 곽복록(옮긴이), 지식공작소, 2004년, 2014년(개정판), 원제: Die Welt von Gestern(1944년), ISBN 979-11-30425-05-4The world of yesterday

- 《다른 의견을 가질 권리》,안인희(옮긴이), 바오, 2009년, 원제: Castellio gegen Calvin oder Ein Gewissen Gegen die Gewalt, ISBN 978-89-91428-07-2

- 《조제프 푸셰. 어느 정치적 인간의 초상》, 정상원 (옮긴이), 이화북스, 2019년, 원제: Joseph Fouché. Bildnis eines politischen Menschen ISBN 979-11-965581-6-1

- 《광기와 우연의 역사. 키케로에서 우드로 윌슨까지》, 정상원 (옮긴이), 이화북스, 2020년, 원제:Sternstunden der Menschheit {ISBN 979-11-90626-06-4}

같이 보기

각주

- Prof.Dr. Klaus Lohrmann "Jüdisches Wien. Kultur-Karte" (2003), Mosse-Berlin Mitte gGmbH (Verlag Jüdische Presse)

- “Egon Hostovský: Vzpomínky, studie a dokumenty o jeho díle a osudu”, Sixty-Eight Publishers, 1974

- Elon, 320

- (영어) Júlia Dias Carneiro (2009년 4월 30일). “Revivendo o país do futuro de Stefan Zweig”. 도이체 벨레. 2012년 2월 23일에 확인함.

- “Stefan Zweig, Wife End Lives In Brazil”. 뉴욕 타임스. 1942년 2월 23일. 2012년 2월 23일에 확인함.

Stefan Zweig, Wife End Lives In Brazil; Austrian-Born Author Left a Note Saying He Lacked the Strength to Go on - Author and Wife Die in Compact: Zweig and Wife Commit Suicide

- (영어) “Died”. 《Time magazine》. 1942년 3월 2일. 2013년 8월 25일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2010년 6월 30일에 확인함.

Died. Stefan Zweig, 60, Austrian-born novelist, biographer, essayist (Amok, Adepts in Self-Portraiture, Marie Antoinette), and his wife, Elizabeth; by poison; in Petropolis, Brazil. Born into a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna, Zweig turned from casual globe-trotting to literature after World War I, wrote prolifically, smoothly, successfully in many forms. His books banned by the Nazis, he fled to Britain in 1938 with the arrival of German troops, became a British subject in 1940, moved to the U.S. the same year, to Brazil the next. He was never outspoken against Naziism, believed artists and writers should be independent of politics. Friends in Brazil said he left a suicide note explaining that he was old, a man without a country, too weary to begin a new life. His last book: Brazil: Land of the Future.

- Fowles, John (1981). 《Introduction to "The Royal Game"》. New York: Obelisk. ix쪽.

- Walton, Stuart (2010년 3월 26일). “Stefan Zweig? Just a pedestrian stylist”. 《가디언》.

- Lezard, Nicholas (2009년 12월 5일). “The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig”. 가디언. 2010년 9월 26일에 확인함.

- Richard Strauss/Stefan Zweig: BriefWechsel, 1957, translated as A Confidential Matter, 1977

- “보관된 사본”. 2021년 5월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2020년 12월 11일에 확인함.

- 최재봉 기자 (2005년 11월 3일). “나치 피해 떠난 케냐에서의 9년”. 한겨레. 2012년 10월 30일에 확인함.[깨진 링크(과거 내용 찾기)]

Stefan Zweig

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2025) |

Stefan Zweig | |

|---|---|

Zweig c. 1927 | |

| Born | 28 November 1881 Vienna, Austria-Hungary (present-day Austria) |

| Died | 22 February 1942 (aged 60) Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Education | University of Vienna (PhD, 1904) |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Signature | |

Stefan Zweig (/zwaɪɡ, swaɪɡ/ ZWYGHE, SWYGHE;[1] German: [ˈʃtɛfan t͡svaɪ̯k] ⓘ or Austrian German: [t͡svaɪ̯g]; 28 November 1881 – 22 February 1942) was an Austrian writer. At the height of his literary career, in the 1920s and 1930s, he was one of the most widely translated and popular writers in the world.[2]

Zweig was raised in Vienna, Austria-Hungary.

He wrote historical studies of famous literary figures, such as

- Honoré de Balzac,

- Charles Dickens, and

- Fyodor Dostoevsky in Drei Meister (1920; Three Masters), and

decisive historical events in

Decisive Moments in History (1927).

He wrote biographies of

- Joseph Fouché (1929),

- Mary Stuart (1935) and

- Marie Antoinette (Marie Antoinette: The Portrait of an Average Woman, 1932), among others.

Zweig's best-known fiction includes

- Letter from an Unknown Woman (1922),

- Amok (1922),

- Fear (1925),

- Confusion of Feelings (1927),

- Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman (1927),

- the psychological novel Ungeduld des Herzens (Beware of Pity, 1939), and

- The Royal Game (1941).

In 1934, as a result of the Nazi Party's rise in Germany and the establishment of the Ständestaat regime in Austria, Zweig emigrated to England and then, in 1940, moved briefly to New York and then to Brazil, where he settled. In his final years, he would declare himself in love with the country, writing about it in the book Brazil, Land of the Future. Nonetheless, as the years passed Zweig became increasingly disillusioned and despairing at the future of Europe, and he and his wife Lotte were found dead of a barbiturate overdose in their house in Petrópolis on 23 February 1942; they had died the previous day. His work has been the basis for several film adaptations.

Zweig's memoir, Die Welt von Gestern (The World of Yesterday, 1942), is noted for its description of life during the waning years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire under Franz Joseph I and has been called the most famous book on the Habsburg Empire.[3]

Biography

Zweig was born in Vienna, the son of Ida Brettauer (1854–1938), a daughter of a Jewish banking family, and Moritz Zweig (1845–1926), a wealthy Jewish textile manufacturer.[4] He was related to the Czech writer Egon Hostovský, who described him as "a very distant relative";[5] some sources describe them as cousins.[citation needed]

Zweig studied philosophy at the University of Vienna and in 1904 earned a doctoral degree with a thesis on "The Philosophy of Hippolyte Taine". Religion did not play a central role in his education. "My mother and father were Jewish only through accident of birth", Zweig said in an interview. Yet he did not renounce his Jewish faith and wrote repeatedly on Jews and Jewish themes, as in his story Buchmendel. Zweig had a warm relationship with Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, whom he met when Herzl was still literary editor of the Neue Freie Presse, then Vienna's main newspaper; Herzl accepted for publication some of Zweig's early essays.[6] Zweig, a committed cosmopolitan,[7] believed in internationalism and in Europeanism, as The World of Yesterday, his autobiography, makes clear: "I was sure in my heart from the first of my identity as a citizen of the world."[8]

Zweig served in the Archives of the Ministry of War and supported Austria's effort for war through his writings in the Neue Freie Presse and frequently celebrated in his Diaries the capture and massacre of opposing soldiers (for instance, writing about the innumerable citizens killed at gunpoint under the suspicion of espionage that "what filth has made ooze must be cauterized with scalding iron".)[9] Zweig judged Serbian soldiers as "hordes" and stated that "one feels proud to talk German" when thousands of French soldiers were captured in Metz.[10] Conversely, in his memoirs, The World of Yesterday, Zweig portrays himself in the role of pacifist at the time of the First World War, states that he refused "to participate in those rabid calumnies against the enemy" (although, through his work in the official Neue Freie Presse, Zweig promoted the war propaganda issued from the Austrian crown) and affirms that among his intellectual friends he was "alone" in his stance against the war.[11]

Zweig married Friderike Maria von Winternitz (born Burger) in 1920; they divorced in 1938. As Friderike Zweig she published a book on her former husband after his death.[12] She later also published a picture book on Zweig.[13] In the late summer of 1939, Zweig married his secretary Elisabet Charlotte "Lotte" Altmann in Bath, England.[14] Zweig's secretary in Salzburg from November 1919 to March 1938 was Anna Meingast (13 May 1881, Vienna – 17 November 1953, Salzburg).[15]

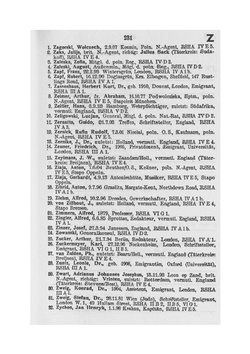

As a Jew, Zweig's high profile did not shield him from the threat of persecution. In 1934, following Hitler's rise to power in Germany and the establishment of the Ständestaat, an authoritarian political regime now known as "Austrofascism", Zweig left Austria for England, living first in London, then from 1939 in Bath. But England was not far enough away from the Nazi threat for Zweig, and in 1940 Zweig and his second wife crossed the Atlantic to the United States, settling in New York City. Zweig was correct to fear that he was target of the Nazis even in England: as part of the preparations for their invasion of England - known as Operation Seelöwe or Operation Sealion - the SS had prepared a list of persons in the UK to be detained immediately. This so-called Black Book came to light after the war; Zweig was listed on page 231, including his London address.

The Zweigs lived only briefly in the US: for two months as guests of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, then renting a house in Ossining, New York. On 22 August 1940, they moved again to Petrópolis, a German-colonized mountain town 68 kilometres north of Rio de Janeiro.[16] There, he wrote the book Brazil, Land of the Future and developed a close friendship with Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral.[17] Zweig, feeling increasingly depressed about the situation in Europe and the future for humanity, wrote in a letter to author Jules Romains, "My inner crisis consists in that I am not able to identify myself with the me of passport, the self of exile".[18] He had been despairing at the future of Europe and its culture. He wrote: "I think it better to conclude in good time and in erect bearing a life in which intellectual labour meant the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on Earth".[19] On 23 February 1942, the Zweigs were found dead of a barbiturate overdose in their house in the city of Petrópolis, holding hands.[20][21]

The Zweigs' house in Brazil was later turned into a cultural centre and is now known as Casa Stefan Zweig.

Work

Zweig was a prominent writer in the 1920s and 1930s, befriending Arthur Schnitzler and Sigmund Freud.[22] He was extremely popular in the United States, South America and Europe, and remains so in continental Europe;[2] however, he was largely ignored by the British public.[23]

His fame in America had diminished until the 1990s, when there began an effort on the part of several publishers (notably Pushkin Press, Hesperus Press, and The New York Review of Books) to get Zweig back into print in English.[24] Plunkett Lake Press has reissued electronic versions of his non-fiction works.[25] Since that time there has been a marked resurgence and a number of Zweig's books are back in print.[26]

Critical opinion of his oeuvre is strongly divided between those who praise his humanism, simplicity and effective style,[24][27] and those who criticize his literary style as poor, lightweight and superficial.[23] In a review entitled "Vermicular Dither", German polemicist Michael Hofmann scathingly attacked the Austrian's work. Hofmann opined that "Zweig just tastes fake. He's the Pepsi of Austrian writing." Even the author's suicide note, Hofmann suggested, induces "the irritable rise of boredom halfway through it, and the sense that he doesn't mean it, his heart isn't in it (not even in his suicide)".[28]

Zweig is best known for his novellas (notably The Royal Game, Amok, and Letter from an Unknown Woman – which was filmed in 1948 by Max Ophüls), novels (Beware of Pity, Confusion of Feelings, and the posthumously published The Post Office Girl) and biographies (notably Erasmus of Rotterdam, Ferdinand Magellan, and Mary, Queen of Scots, and also the posthumously published Balzac). At one time his works were published without his consent in English under the pseudonym "Stephen Branch" (a translation of his real name) when anti-German sentiment was running high. His 1932 biography of Queen Marie Antoinette was adapted by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a 1938 film starring Norma Shearer.

Zweig's memoir,[29][30][31] The World of Yesterday, was completed in 1942 one day before he died by suicide. It has been widely discussed as a record of "what it meant to be alive between 1881 and 1942" in central Europe; the book has attracted both critical praise[24] and hostile dismissal.[28]

Zweig acknowledged his debt to psychoanalysis. In a letter dated 8 September 1926, he wrote to Freud, "Psychology is the great business of my life". He went on explaining that Freud had considerable influence on writers such as Marcel Proust, D.H. Lawrence and James Joyce, giving them a lesson in "courage" and helping them to overcome their inhibitions. "Thanks to you, we see many things. – Thanks to you we say many things which otherwise we would not have seen nor said." He claimed autobiography, in particular, had become "more clear-sighted and audacious".[32]

Zweig enjoyed a close association with Richard Strauss and provided the libretto for Die schweigsame Frau (The Silent Woman). Strauss famously defied the Nazi regime by refusing to sanction the removal of Zweig's name from the programme[33] for the work's première on 24 June 1935 in Dresden. As a result, Goebbels refused to attend as planned, and the opera was banned after three performances. Zweig later collaborated with Joseph Gregor to provide Strauss with the libretto for one other opera, Friedenstag, in 1938. At least[34] one other work by Zweig received a musical setting: the pianist and composer Henry Jolles, who like Zweig had fled to Brazil to escape the Nazis, composed a song, "Último poema de Stefan Zweig",[35] based on "Letztes Gedicht", which Zweig wrote on the occasion of his 60th birthday in November 1941.[36] During his stay in Brazil, Zweig wrote Brasilien, Ein Land der Zukunft (Brazil, A Land of the Future) which consisted in a collection of essays on the history and culture of his newly adopted country.

Zweig was a passionate collector of manuscripts. He corresponded at length with Hungarian musicologist Gisela Selden-Goth, often discussing their shared interest in collecting original music scores.[36] There are important Zweig collections at the British Library, at the State University of New York at Fredonia and at the National Library of Israel. The British Library's Stefan Zweig Collection was donated to the library by his heirs in May 1986. It specialises in autograph music manuscripts, including works by Bach, Haydn, Wagner, and Mahler. It has been described as "one of the world's greatest collections of autograph manuscripts".[37] One particularly precious item is Mozart's "Verzeichnüß aller meiner Werke"[38] – that is, the composer's own handwritten thematic catalogue of his works.

The 1993–1994 academic year at the College of Europe was named in his honour.

Zweig has been credited with being one of the novelists who contributed to the emergence of what would later be called the Habsburg myth.[39]

Bibliography

The dates mentioned below are the dates of first publication in German.

Fiction

- Forgotten Dreams, 1900 (Original title: Vergessene Träume)

- Spring in the Prater, 1900 (Original title: Praterfrühling)

- A Loser, 1901 (Original title: Ein Verbummelter)

- In the Snow, 1901 (Original title: Im Schnee)

- Two Lonely Souls, 1901 (Original title: Zwei Einsame)

- The Miracles of Life, 1903 (Original title: Die Wunder des Lebens)

- The Love of Erika Ewald, 1904 (Original title: Die Liebe der Erika Ewald)

- The Star Over the Forest, 1904 (Original title: Der Stern über dem Walde)

- The Fowler Snared, 1906 (Original title: Sommernovellette)

- The Governess, 1907 (Original title: Die Governante)

- Scarlet Fever, 1908 (Original title: Scharlach)

- Twilight, 1910 (Original title: Geschichte eines Unterganges)

- A Story Told In Twilight, 1911, short story (Original title: Geschichte in der Dämmerung)

- Burning Secret, 1913 (Original title: Brennendes Geheimnis)

- Fear, 1920 (Original title: Angst)

- Compulsion, 1920 (Original title: Der Zwang)

- Fantastic Night, 1922 (Original title: Phantastische Nacht)

- Letter from an Unknown Woman, 1922 (Original title: Brief einer Unbekannten)

- Moonbeam Alley, 1922 (Original title: Die Mondscheingasse)

- Amok, 1922 (Original title: Amok) – novella, initially published with several others in Amok. Novellen einer Leidenschaft

- The Invisible Collection, 1925 (Original title: Die unsichtbare Sammlung, first published in book form in 'Insel-Almanach auf das Jahr 1927'[40])

- Downfall of the Heart, 1927 (Original title: Untergang eines Herzens)

- The Refugee, 1927 (Original title: Der Flüchtling. Episode vom Genfer See).

- Confusion of Feelings or Confusion: The Private Papers of Privy Councillor R Von D, 1927 (Original title: Verwirrung der Gefühle) – novella initially published in the volume Verwirrung der Gefühle: Drei Novellen

- Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman, 1927 (Original title: Vierundzwanzig Stunden aus dem Leben einer Frau) – novella initially published in the volume Verwirrung der Gefühle: Drei Novellen

- Widerstand der Wirklichkeit, 1929 (in English as Journey into the Past (1976))

- Buchmendel, 1929 (Original title: Buchmendel))

- Short stories, 1930 (Original title: Kleine Chronik. Vier Erzählungen) – includes Buchmendel

- Did He Do It?, published between 1935 and 1940 (Original title: War er es?)

- Leporella, 1935 (Original title: Leporella)

- Collected Stories, 1936 (Original title: Gesammelte Erzählungen) – two volumes of short stories:

1. The Chains (Original title: Die Kette)

2. Kaleidoscope (Original title: Kaleidoskop). Includes: Casual Knowledge of a Craft, Leporella, Fear, Burning Secret, Summer Novella, The Governess, Buchmendel, The Refugee, The Invisible Collection, Fantastic Night, and Moonbeam Alley. Kaleidoscope: thirteen stories and novelettes, published by The Viking Press in 1934, includes some of those just listed — some with differently translated titles — plus others. - Incident on Lake Geneva, 1936 (Original title: Episode am Genfer See Revised version of "Der Flüchtung. Episode vom Genfer See", published in 1927)

- The Old-Book Peddler and Other Tales for Bibliophiles, 1937, four pieces (two "clothed in the form of fiction," according to the preface by translator Theodore W. Koch), published by Northwestern University, The Charles Deering Library, Evanston, Illinois:

- "Books are the Gateway to the World"

- "The Old-Book Peddler; A Viennese Tale for Bibliophiles" (Original title: Buchmendel)

- "The Invisible Collection; An Episode from the Post-War Inflation Period" (Original title: Die unsichtbare Sammlung)

- "Thanks to Books"

- Beware of Pity, 1939 (Original title: Ungeduld des Herzens) novel

- Legends, a collection of five short stories published in 1945 (Original title: Legenden – published also as Jewish Legends with "Buchmendel" instead of "The Dissimilar Doubles":

- "Rachel Arraigns with God", 1930 (Original title: "Rahel rechtet mit Gott"

- "The Eyes of My Brother, Forever", 1922 (Original title: "Die Augen des ewigen Bruders")

- "The Buried Candelabrum", 1936 (Original title: "Der begrabene Leuchter")

- "The Legend of The Third Dove", 1945 (Original title: "Die Legende der dritten Taube")

- "The Dissimilar Doubles", 1927 (Original title: "Kleine Legende von den gleich-ungleichen Schwestern")

- The Royal Game or Chess Story or Chess (Original title: Schachnovelle; Buenos Aires, 1942) – novella written in 1938–41,

- Clarissa, 1981 unfinished novel

- The Debt Paid Late, 1982 (Original title: Die spät bezahlte Schuld)

- The Post Office Girl, 1982 (Original title: Rausch der Verwandlung. Roman aus dem Nachlaß; The Intoxication of Metamorphosis)

- Schneewinter: 50 zeitlose Gedichte, 2016, editor Martin Werhand. Melsbach, Martin Werhand Verlag 2016

Biographies and historical texts

- Émile Verhaeren (the Belgian poet), 1910

- Three Masters: Balzac, Dickens, Dostoevsky, 1920 (Original title: Drei Meister. Balzac – Dickens – Dostojewski. Translated into English by Eden and Cedar Paul and published in 1930 as Three Masters)

- Romain Rolland: The Man and His Work, 1921 (Original title: Romain Rolland. Der Mann und das Werk)

- Nietzsche, 1925 (Originally published in the volume titled: Der Kampf mit dem Dämon. Hölderlin – Kleist – Nietzsche)

- Decisive Moments in History, 1927 (Original title: Sternstunden der Menschheit). Translated into English and published in 1940 as The Tide of Fortune: Twelve Historical Miniatures;[41] retranslated in 2013 by Anthea Bell as Shooting Stars: Ten Historical Miniatures[42] Great moments of humanity

- Adepts in Self-Portraiture: Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy, 1928 (Original title: Drei Dichter ihres Lebens. Casanova – Stendhal – Tolstoi)

- Joseph Fouché, 1929 (Original title: Joseph Fouché. Bildnis eines politischen Menschen)

- Mental Healers: Franz Mesmer, Mary Baker Eddy, Sigmund Freud, 1932 (Original title: Die Heilung durch den Geist. Mesmer, Mary Baker-Eddy, Freud)

- Marie Antoinette: The Portrait of an Average Woman, 1932 (Original title: Marie Antoinette. Bildnis eines mittleren Charakters) ISBN 4-87187-855-4

- Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1934 (Original title: Triumph und Tragik des Erasmus von Rotterdam)

- Maria Stuart, 1935 (also published as: The Queen of Scots or Mary Queen of Scots) ISBN 4-87187-858-9

- A Conscience Against Violence or The Right to Heresy: Castellio against Calvin, 1936 (Original title: Castellio gegen Calvin oder Ein Gewissen gegen die Gewalt)

- Conqueror of the Seas: The Story of Magellan, 1938 (Original title: Magellan. Der Mann und seine Tat) ISBN 4-87187-856-2

- Montaigne (the French philosopher), 1941 ISBN 978-1782271031

- Amerigo, 1942 (Original title: Amerigo. Geschichte eines historischen Irrtums) – written in 1942, published the day before he died[citation needed] ISBN 4-87187-857-0

- Balzac, 1946 – written, as Richard Friedenthal describes in a postscript, in the Brazilian summer capital of Petrópolis, without access to the files, notebooks, lists, tables, editions and monographs that Zweig accumulated for many years and that he took with him to Bath, but that he left behind when he went to America. Friedenthal wrote that Balzac "was to be his magnum opus, and he had been working at it for ten years. It was to be a summing up of his own experience as an author and of what life had taught him." Friedenthal claimed that "The book had been finished", though not every chapter was complete; he used a working copy of the manuscript Zweig left behind him to apply "the finishing touches", and Friedenthal rewrote the final chapters (Balzac, translated by William and Dorothy Rose [New York: Viking, 1946], pp. 399, 402).

- Paul Verlaine (the French poet), Copyright 1913, By L. E. Basset Boston, Mass., USA. English translation by O. F. Theis. Luce and Company Boston. Maunsel and Co. Ltd Dublin and London.

Plays

- Tersites, 1907

- Das Haus am Meer, 1912

- Jeremiah, 1917

- Ben Jonson's Volpone. A Loveless Comedy in 3 Acts, freely adapted, 1928

Other

- The World of Yesterday (Original title: Die Welt von Gestern; Stockholm, 1942) – autobiography

- Brazil, Land of the Future (Original title: Brasilien. Ein Land der Zukunft; Bermann-Fischer, Stockholm 1941)

- Journeys (Original title: Auf Reisen; Zurich, 1976); collection of essays

- Encounters and Destinies: A Farewell to Europe (2020); collection of essays

Letters

- Darién J. Davis; Oliver Marshall, eds. (2010). Stefan and Lotte Zweig's South American Letters: New York, Argentina and Brazil, 1940–42. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-1441107121.

- Henry G. Alsberg, ed. (1954). Stefan and Friderike Zweig: Their Correspondence, 1912–1942. New York: Hastings House. OCLC 581240150.

Adaptations

The 1924 German silent film The House by the Sea (Das Haus am Meer) directed by Fritz Kaufmann was based on Zweig's play of the same name.

The 1933 Austrian-German drama film The Burning Secret directed by Robert Siodmak was based on Zweig's short story Brennendes Geheimnis. The 1988 remake of the same film Burning Secret was directed by Andrew Birkin and starred Klaus Maria Brandauer and Faye Dunaway.

Letter from an Unknown Woman was filmed in 1948 by Max Ophüls.

Beware of Pity was adapted into a 1946 film with the same title, directed by Maurice Elvey.[43]

Letter from an Unknown Woman was filmed in 1962 by Salah Abu Seif.

An adaptation by Stephen Wyatt of Beware of Pity was broadcast by BBC Radio 4 in 2011.[44]

The 2012 Brazilian film The Invisible Collection, directed by Bernard Attal, is based on Zweig's short story of the same title.[45]

The 2013 French film A Promise (Une promesse) is based on Zweig's novella Journey into the Past (Reise in die Vergangenheit).

The 2013 Swiss film Mary Queen of Scots, directed by Thomas Imbach, is based on Zweig's Maria Stuart.[46]

The end-credits for Wes Anderson's 2014 film The Grand Budapest Hotel say that the film was inspired in part by Zweig's novels. Anderson said that he had "stolen" from Zweig's novels Beware of Pity and The Post Office Girl in writing the film, and it features actors Tom Wilkinson as The Author, a character based loosely on Zweig, and Jude Law as his younger, idealised self seen in flashbacks. Anderson also said that the film's protagonist, the concierge Gustave H., played by Ralph Fiennes, was based on Zweig. In the film's opening sequence, a teenage girl visits a shrine for The Author, which includes a bust of him wearing Zweig-like spectacles and celebrated as his country's "National Treasure".[47]

The 2017 Austrian-German-French film Vor der Morgenröte (Stefan Zweig: Farewell to Europe) chronicles Stefan Zweig's travels in the North and South Americas, trying to come to terms with his exile from home.

The 2018 American short film Crepúsculo by Clemy Clarke is based on Zweig's short story "A Story Told in Twilight" and relocated to a quinceañera in 1980s New York.[48]

TV film La Ruelle au clair de lune (1988) by Édouard Molinaro is an adaptation of Zweig's short-story Moonbeam Alley.[49]

Schachnovelle, translated as The Royal Game and as Chess Story, was the inspiration for the 1960 Gerd Oswald film Brainwashed,[50] as well as for two Czechoslovakian films—the 1980 Královská hra (The Royal Game) and Šach mat (Checkmate), made for television in 1964[51]—and for the 2021 Philipp Stölzl film Chess Story.[52][53]

See also

- Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century, a list which includes Confusion of Feelings

References

- "Zweig". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Kavanagh, Julie (Spring 2009). "Stefan Zweig: The Secret Superstar". Intelligent Life. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012.

- Giorgio Manacorda (2010) Nota bibliografica in Joseph Roth, La Marcia di Radetzky, Newton Classici quotation: "Stefan Zweig, l'autore del più famoso libro sull'Impero asburgico, Die Welt von Gestern

- Prof.Dr. Klaus Lohrmann "Jüdisches Wien. Kultur-Karte" (2003), Mosse-Berlin Mitte gGmbH (Verlag Jüdische Presse)

- Egon Hostovský: Vzpomínky, studie a dokumenty o jeho díle a osudu, Sixty-Eight Publishers, 1974

- Friedman, Gabe (17 January 2015). "Meet the Austrian-Jewish novelist who inspired Wes Anderson's 'The Grand Budapest Hotel'". Haaretz.com.

- Epstein, Joseph (June 2019). "Stefan Zweig, European Man". First Things. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- Zweig, Stefan (1942). "Chapter IX: The First Hours of the War of 1914". The World of Yesterday. Chapter IX, paragraph 20 beginning "As a result": Kindle location code 3463: Plunkett Lake Press (ebook).

- Stach, Reiner (2008). Reiner Stach – Kafka. Die Jahre der Erkenntnis. Fráncfort del Meno: S. Fischer Verlag. p. 1365.

- Stach, Reiner (2008). Reiner Stach – Kafka. Die Jahre der Erkenntnis. Fráncfort del Meno: S. Fischer Verlag. p. 1366.

- Zweig, Stefan (2013). Stefan Zweig – The World of Yesterday. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 130–141.

- Zweig, Friderike (1948). Stefan Zweig – Wie ich ihn erlebte. Berlin: F. A. Herbig Verlag.

- Zweig, Friderike (1961). Stefan Zweig : Eine Bildbiographie. München: Kindler.

- "Index entry for marriage of Altmann, Elisabet C., Spouse:Zweig, Registration district: Bath Register volume & page nbr: 5c, 1914". Transcription of England and Wales national marriage registrations index 1837–1983. ONS. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Thuswaldner, Werner (14 December 2000). "Wichtiges zu Stefan Zweig: Das Salzburger Literaturarchiv erhielt eine bedeutende Schenkung von Wilhelm Meingast" [Important to Stefan Zweig: The Salzburg Literature Archive received a significant donation from Wilhelm Meingast]. Salzburger Nachrichten (in German). Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Dias Carneiro, Júlia (30 April 2009). "Revivendo o país do futuro de Stefan Zweig" [Reviving the country of the future according to Stefan Zweig] (in Portuguese). Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- Lawrence, Edward (2018). ""In This Dark Hour": Stefan Zweig and Historical Displacement in Brazil, 1941–1942". Journal of Austrian Studies. 51 (3): 1–20. ISSN 2165-669X. JSTOR 26575129. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Prochnik, George (6 February 2017). "When It's Too Late to Stop Fascism, According to Stefan Zweig". The New Yorker. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- Banville, John (27 February 2009). "Ruined souls". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "Stefan Zweig, Wife End Lives In Brazil". The New York Times. The United Press. 23 February 1942. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "Milestones, Mar. 2, 1942". Time. 2 March 1942. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Fowles, John (1981). Introduction to "The Royal Game". New York: Obelisk. pp. ix.

- Walton, Stuart (26 March 2010). "Stefan Zweig? Just a pedestrian stylist". The Guardian. London.

- Lezard, Nicholas (5 December 2009). "The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Plunkett Lake Press". Stefan Zweig.

- Rohter, Larry. "Stefan Zweig, Austrian Novelist, Rises Again". The New York Times. 28 May 2014

- Liukkonen, Petri (2008). "Stefan Zweig". Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015 – via kirjasto.sci.fi.

- Hofmann, Michael (2010). "Vermicular Dither". London Review of Books. 32 (2): 9–12. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- Jones, Lewis (11 January 2010), "The World of Yesterday", The Telegraph, archived from the original on 12 January 2022, retrieved 2 November 2015

- Lezard, Nicholas (4 December 2009), "The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig", The Guardian, retrieved 2 November 2015

- Brody, Richard (14 March 2014), "Stefan Zweig, Wes Anderson, and a Longing for the Past", The New Yorker, retrieved 2 November 2015

- Sigmund Freud, Stefan Zweig, Correspondance, Editions Rivages, Paris, 1995, ISBN 978-2869309654

- Richard Strauss/Stefan Zweig: BriefWechsel, 1957, translated as A Confidential Matter, 1977

- "Author: Stefan Zweig (1881–1942)". REC Music Foundation. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Musica Reanimata of Berlin, Henry Jolles accessed 25 January 2009

- Biographical sketch of Stefan Zweig at Casa Stefan Zweig accessed 28 September 2008

- "The Zweig Music Collection". bl.uk. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- Mozart's "Verzeichnüß aller meiner Werke" Archived 7 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine at the British Library Online Gallery accessed 14 October 2009

- Thompson, Helen (2020). "The Habsburg Myth and the European Union". In Duina, Francesco; Merand, Frédéric (eds.). Europe's Malaise: The Long View. Research in Political Sociology. Vol. 27. Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 45–66. doi:10.1108/S0895-993520200000027005. ISBN 978-1-83909-042-4. ISSN 0895-9935. S2CID 224991526.

- "Die unsichtbare sammlung". Open Library. OL 6308795M. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "Stefan Zweig." The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Encyclopedia.com. 21 November 2010.

- "Shooting Stars: Ten Historical Miniatures". Pushkin Press. 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Beware of Pity (1946)". BFI. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012.

- "Classic Serial: Stefan Zweig – Beware of Pity". Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- "The Invisible Collection (A Coleção Invisível): Rio Review". The Hollywood Reporter. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Mary Queen of Scots (2013) at IMDb

- Anderson, Wes (8 March 2014). "'I stole from Stefan Zweig': Wes Anderson on the author who inspired his latest movie". The Daily Telegraph (Interview). Interviewed by George Prochnik. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Crepúsculo (2018) at IMDb

- La ruelle au clair de lune. Auteur Production Group. OCLC 494237410.

- Brainwashed (1960)

- "Sach [Šach] mat". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- "Schachnovelle". IMDb.

- Smith, Kyle (12 January 2023). "'Chess Story' Review: Stefan Zweig's Novella of Playing the Nazis' Game". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023.

Further reading

- Elizabeth Allday, Stefan Zweig: A Critical Biography, J. Philip O'Hara, Inc., Chicago, 1972, ISBN 978-0879553012

- Alberto Dines, Morte no Paraíso, a Tragédia de Stefan Zweig, Editora Nova Fronteira 1981, (rev. ed.) Editora Rocco 2004

- Alberto Dines, Tod im Paradies. Die Tragödie des Stefan Zweig, Edition Büchergilde, 2006

- Rüdiger Görner, In the Future of Yesterday: A Life of Stefan Zweig, Haus Publishing, 2024, ISBN 9781914979101

- Randolph J. Klawiter, Stefan Zweig. An International Bibliography, Ariadne Press, Riverside, 1991, ISBN 978-0929497358

- Martin Mauthner, German Writers in French Exile, 1933–1940, Vallentine Mitchell, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-85303-540-4

- Oliver Matuschek, Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig, translated by Allan Blunden, Pushkin Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1906548292

- Donald A. Prater, European of Yesterday: A Biography of Stefan Zweig, Holes and Meier, (rev. ed.) 2003, ISBN 978-0198157076

- George Prochnik, The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World, Random House, 2014, ISBN 978-1590516126

- Giorgia Sogos, Le Biografie di Stefan Zweig tra Geschichte e Psychologie: Triumph und Tragik des Erasmus von Rotterdam, Marie Antoinette, Maria Stuart, Firenze University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-88-6655-508-7

- Giorgia Sogos, Ein Europäer in Brasilien zwischen Vergangenheit und Zukunft. Utopische Projektionen des Exilanten Stefan Zweig, in: Lydia Schmuck, Marina Corrêa (Hrsg.): Europa im Spiegel von Migration und Exil / Europa no contexto de migração e exílio. Projektionen – Imaginationen – Hybride Identitäten/Projecções – Imaginações – Identidades híbridas, Frank & Timme Verlag, Berlin, 2015, ISBN 978-3-7329-0082-4

- Giorgia Sogos, Stefan Zweig, der Kosmopolit. Studiensammlung über seine Werke und andere Beiträge. Eine kritische Analyse, Free Pen Verlag, Bonn, 2017, ISBN 978-3-945177-43-3

- Giorgia Sogos Wiquel, L’esilio impossibile. Stefan Zweig alla fine del mondo, in: Toscana Ebraica. Bimestrale di notizie e cultura ebraica. Anno 34, n. 6. Firenze: Novembre-Dicembre 2021, Cheshwan – Kislew- Tevet 5782, Firenze, 2022, ISSN 2612-0895

- Marion Sonnenfeld (editor), The World of Yesterday's Humanist Today. Proceedings of the Stefan Zweig Symposium, texts by Alberto Dines, Randolph J. Klawiter, Leo Spitzer and Harry Zohn, State University of New York Press, 1983

- Vanwesenbeeck, Birger; Gelber, Mark H. (2014). Stefan Zweig and World Literature: Twenty-First-Century Perspectives. Rochester: Camden House. ISBN 9781571139245.

- Volker Weidermann. Ostend: Stefan Zweig, Joseph Roth, and the Summer Before the Dark. Translated from the German by Carol Brown Janeway. New York: Pantheon Books, 2016, ISBN 978-1-101-87026-6

- Friderike Zweig, Stefan Zweig, Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1946 (account of his life by his first wife)

External links

- StefanZweig.org

- StefanZweig.de

- Stefan Zweig Centre Salzburg[usurped]

- Home page, Casa Stefan Zweig

- "Stefan Zweig and Chess" by Edward Winter

- "No Exit", article on Zweig at Tablet Magazine

- "To Friends in Foreign Land" – Zweig's letter, which he published in the newspaper Berliner Tageblatt, on September 19, 1914

- Zweig's foreword to The World of Yesterday

- Stefan Zweig at perlentaucher.de – das Kulturmagazin (in German)

- Guide to the Correspondence of Stefan Zweig and Siegmund Georg Warburg at the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

- Stefan Zweig at IMDb

Libraries

- Zweig Music Collection at the British Library Archived 11 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Stefan Zweig Collection at the Daniel A. Reed Library, State University of New York at Fredonia, Fredonia, New York Archived 6 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Stefan Zweig Online Bibliography, a wiki hosted by Stefan Zweig Digital, in Salzburg, Austria

- Stefan Zweig's suicide letter on the National Library of Israel's website

Electronic editions

- Works by Stefan Zweig at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Stefan Zweig at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Stefan Zweig at the Internet Archive

- Works by Stefan Zweig at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

슈테판 츠바이크 일본어

슈테판 츠바이크 Stefan Zweig | |

|---|---|

| |

| 탄생 | 1881년 11월 28일 오스트리아=헝가리 제국 비엔나 |

| 사망 | 1942년 2월 22일 (60세) 브라질 페트로폴리스 |

| 직업 | 소설가 , 비평가 |

| 국적 | |

| 장르 | 역사소설 , 평전 |

| 문학 활동 | 청소년 비엔나 |

| 대표작 | 『마리 앙투아네트』(1933년) 『메리 스튜어트』(1935년) |

| 서명 | |

슈테판 츠바이크 ( 트 와 이크 [ 주 1 ] 와도. 독 : Stefan Zweig ,[tsvaɪk] , 발음 예 , 1881년 11월 28일 - 1942년 2월 22일 )는 오스트리아 의 유대계 작가· 평론가 이다 .

1930년대부터 40년대에 걸쳐 매우 고명으로 많은 전기 문학과 단편, 희곡을 저술했다. 특히 전기 문학의 평가가 높고 『마리 앙투아네트』나 『메리 스튜어트』 『조제프 푸쉐』 등의 저서가 있다.

제1차 세계대전 직후의 미국에서, 트바이크의 소설의 무허가의 번역이 출판되었을 때에는, 대독 감정의 악화를 이유로, 「Stephen Branch」 (츠바이크의 본명의 영역)」라고 하는 가명으로 간행되었다.

평생

츠바이크는 비엔나 극히 부유한 유대계 직물 공장주인 모리츠 츠바이크와 아내(이탈리아인의 은행가의 일족 출신)의 이다 사이에서 태어났다. 비엔나 대학 에서 철학과 문학사를 배우고, 1904년 박사 논문 ‘ 이폴리트 테누 의 철학’에서 철학 박사 학위를 취득했다(이 박사 학위는 1941년, 나치 지배하의 오스트리아 에서 ‘인종적 이유로부터’ 박탈당해 2003년 4월이 되어 회복되었다.

츠바이크는 세기 말 비엔나 의 뛰어난 문화적 환경 하에서 김나듐 시대부터 문학, 예술에 친해지고 있었다. 호프만 스탈 의 흐름을 펌핑하는 신로만 주의(파)풍의 서정시 인으로 출발한다. 시집 『은의 현』(원제 Silverne Saiten , 1901년)에서 문단에 데뷔. 당시의 전위 운동인 청년 비엔나 운동에 관여했다.

제1차 세계대전 개전 후, 병역을 면한 츠바이크는 오스트리아의 전시 문서과의 군무에 대해, 혼미하는 세상으로부터 끌어들여 살려고 했다. 하지만 갈리치아 전쟁에 접한 것, 로만 로랑 과의 교제 등에서 반전에 대한 저술 활동을 활발화시킨다. 반전극 '예레미야 '(원제 Jeremias )의 초연을 계기로 중립국이었던 스위스 취리히 에 건너온다. 그 후 '비엔나 신자유 신문'(원제 Neue Freie Presse )의 특파원으로서 기사를 보내는 것을 조건으로 스위스에 머물러, 로랑 등 모두 반전 평화와 전후의 화해를 향한 활동에 종사한다.

제1차 대전 후는 오스트리아 로 돌아가 1919년 부터 1934년 까지 잘츠부르크 에 체재한다. 잘츠부르크의 거주지는 카푸치나베르크의 패싱거 성이었다. 1920년 에 프리드리케 폰 빈터니츠 (Friderike von Winternitz )와 결혼한다. 이후 널리 지식인과 교제하기 시작해 유럽의 정신적 독립을 위해 노력했다. 이 기간에는 많은 대표작이 쓰여졌으며, 그 중에서도 1927년 의 ' 인류의 별의 시간 ' [ 1 ] 은 독일어권에서는 그의 대표작으로 여겨지고 있다. 1928년 에는 소비에트 연방을 여행하여 막심 고리키 와 교제한다. 1930년 에는 미국으로 여행해 망명 중인 알베르트 아인슈타인을 만나 '정신에 의한 치료'(원제: Heilung durch den Geist )를 헌정한다. 1933년 히틀러 의 독일 제국 총리 취임 전후부터 오스트리아에서도 반유태주의적 분위기가 강해지고, 1934년 무기소유의 혐의로 잘츠부르크의 집이 수색을 받은 것을 계기로 유태인으로 평화주의자였던 츠바이크는 영국 으로 망명한다.

츠바이크는 그 후 영국(버스와 런던)에 머물며 1940년 미국으로 옮겼다. 1941년에는 브라질로 이주. 1942년 2월 22일, 유럽과 그 문화의 미래에 절망해, 브라질의 페트로폴리스 에서 , 1939년 에 재혼한 두 번째 아내인 롯데(Charlotte Altmann)와 함께, 바르비툴 제제의 과량 섭취에 의해 자살 했다. 죽음 1주일 전에는 구 일본군에 의한 싱가포르 함락의 보에 접해( 싱가포르의 싸움 ), 동시기에 리오데자네이루 의 카니발을 보고 있어, 자신들이 있는 곳과 유럽과 아시아에서 행해지고 있는 현실의 갭을 견디지 못하고, 점점 비관한 것 같다.

유저가 된 '어제의 세계'는 자신의 회상록에서 저자가 잃어버린 것으로 생각한 유럽 문명에 대한 찬송이기도 하며 오늘날에도 20세기 의 증언으로도 읽혀지고 있다.

작곡가 리하르트 스트라우스 가 나치 정권 하에서 자신의 작품 가극 '무구한 여자 '(원제 Die schweigsame Frau )에서 대본 작가로서 츠바이크 이름의 크레딧을 지키기 위해 싸운 것은 잘 알려져 있다. 이 때문에, 아돌프 히틀러 는 예정되어 있던 이 가극의 초연에 출석을 멈추고, 결국 이 가극은, 3회의 공연 후에 상연 금지로 되었다.

2009년 3월 이 되어 츠바이크의 죽음에 하나의 설이 나왔다. 그것은 미국 해군이 신형 구축함에 "슈테판 츠바이크"의 이름을 붙이려고 하고, 그 일을 알게 된 츠바이크가 점점 절망했다는 설이다 [ 요출전 ] . 그 항의의 편지( 편지 의 주님은, 트바이크와 친교가 있던 작가 토마스 맨이었다고 생각된다)에 의해, 미국 해군 작전 부장 어니스트·킹 은, 신형 구축함에 츠바이크의 이름을 붙이는 것을 취소하는 명령을 했다고 한다.

정보이공학의 연구자로 하여 가인 의 사카이 슈이치 는 “츠바이크에게 맨 에게 망명의 땅은 있어 세계 한사람들에게는 없음”이라는 노래를 읊고 있다 [ 2 ] .

주요 작품

- 1901년 Silverne Saiten (『은의 현』, 시집)

- 1907년 Tersites (『텔디테스』, 연극)

- 1917년 Jeremias (『예레미야』, 연극)

- 1920년 Drei Meister (『3명의 거장』, 평전)

- 1922년 Amok (『아모쿠』, 단편집)

- 1925년 Der Kampf mit dem Dämon (『데몬과의 투쟁』, 평전)

- 1927년 Verwirrung der Gefühle (『 감정의 혼란』, 단편집)

- 1927년 Sternstunden der Menschheit (『인류의 별의 시간』[ 1 ] , 역사적 단편집:전 5작)

- 1943년 Sternstunden der Menschheit (『인류의 별의 시간』, 역사적 단편집 :전 12작, 상기를 증보)

- 1928년 Dri Dichter ihres Lebens (『3명의 자전 작가 』, 평론)

- 1929년 Joseph Fouché (『조제프 푸쉐』, 평전)

- 1932년 Marie Antoinette (『마리 앤트워넷 』, 평전) [ 주 2 ]

- 1934년 Triumph und Tragik des Erasmus von Rotterdam (『엘라스무스의 승리와 비극』 , 평전)

- 1935년 Maria Stuart (『메리 스튜어트 』, 평전)

- 1936년 Castellio gegen Calvin. Ein Gewissen gegen die Gewalt

- (『권력과 두드리는 양심』, 평전: 장 칼빈 의 종교 독재에 반대한 세바스찬 카스텔로를 다룬다).

- 1939년 Ungeduld des Herzens (『마음의 초조』, 소설)

- 1942년 Die Welt von Gestern (『어제의 세계 』, 회상)

- 1942년 Schachnovelle (『체스의 이야기』, 중편)

- 몰후 Honore de Balzac (『발작 』, 평전.미완의 대작)

오페라

츠바이크가 대본 또는 그 원안을 만든 오페라 . 모두 리하르트 스트라우스의 작곡.

주요 일본어 번역

- 전집

- 『츠바이크 전집』, 미스즈 서방 (전 21권) [ 주 3 ] , 신판 1979년 - 1980년. 제1권: ISBN 978-4-622-00001-3 - 제21권: ISBN 978-4-622-00021-1

- 이하는 신장판(미스즈 서방)

- 「전기 문학 컬렉션」(전 6권, 1998년 8월 - 11월. 제1권: ISBN 978-4-622-04661-5 - 제6권: ISBN 978-4-622-04666-0 )

- 「인류의 별의 시간」카타야마 토시히코 역, 미스즈 라이브러리, 1996년 9월. ISBN 978-4-622-05006-3 . 구텐베르크 21 ( 전자 서적 )에서 재간

- 「어제의 세계 I・II」하라다 요시히토역 , 미스즈 라이브러리, 1999년 3월. ISBN 978-4-622-05034-6 , 978-4-622-05035-3 . 구텐베르크 21에서 재간

- 「체스의 이야기 츠바이크 단편 선」관 쿠생・우치가키 케이이치 외역 , 미스즈 서방〈어른의 책장〉, 2011년 8월. ISBN 978-4-622-08091-6 .

- 「여자의 24시간 츠바이크 단편선」오쿠보 카즈로 외역 , 미스즈 서방 <어른의 책장>, 2012년 6월. ISBN 978-4-622-08501-0 .

- 기타

- “역사의 결정적 순간” 히카루 번역, 시라미즈 샤 , 1969 년. 전국 서지 번호 : 64009331 , NCID BN05192709 .

- 시라미즈샤 , 신판 1997년 10월. ISBN 978-4-560-02806-3 . 「인류의 별의 시간」의 초역판

- 「발작」미즈노 료역 , 하야카와 서방 , 1959년 6월. 전국 서지 번호 : 59010494 , NCID BN05553625 .

- 신판·하야카와 서방, 1980년 4월. 중공 문고 (상하), 2023년 11월. ISBN 978-4-12-207445-3 , 978-4-12-207446-0 . 전자책도 간행

- 『조제프 푸쉐 있는 정치적 인간의 초상』아키야마 히데오 , 타카하시 료지

- 이와나미 문고 , 1979년 3월, 개판 2011년 12월. NCID BN00904686 , ISBN 978-4-00-324374-9 .

- 『 조제프 푸쉐 있는 정치적 인간 의 초상』 야마시타 조 · 야마시타 만리

- '조제프 푸쉐 ' 후쿠다 히로시 연역 , 구텐베르크 21에서 재간

- " 마리 앙투아네트 "

- 『변신의 매혹』이즈카 노부오 역, 아사히 신문 출판 , 1986년 4월. ISBN 978-4-02-255498-7 .

- 『츠바이크 단편 소설집』 나가사카 사토역, 히라하라사, 2001년 2월. ISBN 978-4-938391-25-6 .

- 『성전』 우와가와 유, 籠碧 번역, 환희 서방 〈 루리유르서〉, 2020년. ISBN 978-4-86-488205-7 .

- 『과거에의 여행 ISBN 978-4-86-488223-1 .

- '4명의 거장' 시바타 쇼 외역, '구텐베르크 21'에서 재간 - 발작, 디 켄스, 도스토예프스키, 몬테뉴의 4자

- ※그 밖에 『마젤란』칸쿠생・가와라 타다히코역이 동・재간

- 자료문헌

- 『미래의 나라 브라질』 미야오카 세이지 번역, 카와데 서방 신사, 1993 년 1월. ISBN 978-4-309-22239-4 .

- 『츠바이크 일기 1912-1940』쿠누트・벡편, 후지와라 카즈오 번역, 동양 출판, 2012년 12월. ISBN 978-4-8096-7675-8 . 나중에 전자 서적화

영상화 작품

- 원작 - 소설 ' 미지의 여자의 편지 '

- 원작 - 소설 ' 마리 앙투아네트 '

- 마리 앙투아넷의 생애 (1938년, 미국 영화)

- 원작 - 소설 Reise in die Vergangenheit

- A Promise (2013년, 프랑스 영화)

전기

- 가와라 타다히코『슈테판 츠바이크―유럽 통일 환상을 살았던 전기 작가』중앙 공론사 < 중공 신서 >, 1998년 2월. ISBN 978-4-12-101404-7 . NCID BA34727295 .

- 후지와라 카즈오 『추상의 츠바이크 작열과 편력〈청춘편〉』 동양 출판, 2008년 11월. ISBN 978-4-8096-7583-6 .

관련작품

- 『슈테판 츠바이크』 - 제르마 메아바움=아이징거 (유대계 독일어 시인)가 1941년 12월 24일에 만든 시.

- 「베르사유 의 장미」- 이케다 리요코 에 의한 만화. 츠바이크 『마리 앤트와넷』을 참고로 하고 있다.

각주

주석

출처

- ↑ a b “ 슈테판 츠바이크 | 인류의 별의 시간 | ARCHIVE ”. ARCHIVE . 2023년 12월 24일에 확인함.

- ^ 사카이 슈이치 “도중 소음”(혼아미 서점)에 게재. 주니치 신문 2023년 9월 9일, 석간 5면, 오모리 시즈카 「오모리 시즈카의 단가 연락선」에 의한다.

참고문헌

- 제르마·M=아이징가『제르마의 시집 강제수용소에서 죽은 유대인 소녀』아키야마 히로메 /해설, 이와나미 서점〈이와 나미 주니어 신서(119)〉, 1986년 12월 19일. ISBN 978-4-00-500119-4 . NCID BN06420343 .

관련 서적

- 서부 매, 사다카 노부 「츠바이크 「조셉 푸쉐」」 「 서부 매 와 사고 노부의 쾌저 쾌독」 코분샤 , 2012년 10월 18일, 9-46쪽. ISBN 978-4-334-97716-0 .

외부 링크

- 모래 원교 남자 「슈테판 츠바이크 의 비극(위)」 「인문학 논집」 제9-10호, 오사카 부립 대학 인문 학회, 1991년 3월 20 일, 21-28페이지, doi : 10.24729/00004635 , ISSN 0289 120006720806 .

- 모래 원교 남자 「슈테판 츠바이크 의 비극(중)」 「인문학 논집」 제11호, 오사카 부립 대학 인문 학회, 1993년 3월 1일, 49-57페이지, doi : 10.24729 / 00004624 , ISSN 0280-06 .

- 야마자키 미츠 히코 「프랑스에서의 슈테판 츠바이크 연구의 일단 : 독일에서의 무관심과 프랑스에서의 다카모리」 「국제문화논집」 제17호, 1998년 2월 28일, 43-54페이지, ISSN 0917-0219 , NAID 11000469 1420/00007837 .

- 슈테판 츠바이크 '인류의 별의 시간'(서문·초판 서문) - ARCHIVE.