Want to read

Buy on Kobo

Rate this book

Edit my activity

Beware of Pity

Stefan Zweig, Phyllis Blewitt (Translator), Trevor Blewitt (Translator)

4.26

20,115 ratings2,368 reviews

The great Austrian writer Stefan Zweig was a master anatomist of the deceitful heart, and Beware of Pity, the only novel he published during his lifetime, uncovers the seed of selfishness within even the finest of feelings.

Hofmiller, an Austro-Hungarian cavalry officer stationed at the edge of the empire, is invited to a party at the home of a rich local landowner, a world away from the dreary routine of his barracks. The surroundings are glamorous, wine flows freely, and the exhilarated young Hofmiller asks his host's lovely daughter for a dance, only to discover that sickness has left her painfully crippled. It is a minor blunder, yet one that will go on to destroy his life, as pity and guilt gradually implicate him in a well-meaning but tragically wrongheaded plot to restore the unhappy invalid to health.

GenresFictionHistorical FictionGerman LiteratureLiteratureNovelsLiterary Fiction20th Century

...more

353 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1939

Original title

Ungeduld des Herzens

Setting

Vienna (Austria, 1914)

Characters

Anton Hofmiller, Edith von Kekesfalva, Doctor Condor, Lajos Kekesfalva

This edition

Format

353 pages, Paperback

Published

June 20, 2006 by NYRB Classics

Language

English

More editions

Paperbackالمؤسسة العربية الحديثة للطبع والنشر والتوزيع2002

PaperbackAcantilado2006

Kindle EditionNYRB Classics2012

PaperbackPenguin Books Ltd2016

PaperbackCan Yayınları2016

PaperbackGrasset2002

PaperbackPushkin Press2013

HardcoverАСТ2001

PaperbackFISCHER Taschenbuch1988

PaperbackΆγρα2012

PaperbackVaga2013

PaperbackL.J. Veen2014

Kindle EditionPushkin Press2011

Paperbackელფის გამომცემლობა

Kindle EditionRupa Publications2018

PaperbackPushkin Press

HardcoverAltın Kitaplar Yayınevi1973

PaperbackPenguin2024

PaperbackPolirom2017

Show all 349 editions

More information

Book statistics

Fewer details

12 people are currently reading

169 people want to read

About the author

Stefan Zweig2,066 books10.1k followers

Follow

Stefan Zweig was one of the world's most famous writers during the 1920s and 1930s, especially in the U.S., South America, and Europe. He produced novels, plays, biographies, and journalist pieces. Among his most famous works are Beware of Pity, Letter from an Unknown Woman, and Mary, Queen of Scotland and the Isles. He and his second wife committed suicide in 1942.

Zweig studied in Austria, France, and Germany before settling in Salzburg in 1913. In 1934, driven into exile by the Nazis, he emigrated to England and then, in 1940, to Brazil by way of New York. Finding only growing loneliness and disillusionment in their new surroundings, he and his second wife committed suicide.

Zweig's interest in psychology and the teachings of Sigmund Freud led to his most characteristic work, the subtle portrayal of character. Zweig's essays include studies of Honoré de Balzac, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoevsky (Drei Meister, 1920; Three Masters) and of Friedrich Hölderlin, Heinrich von Kleist, and Friedrich Nietzsche (Der Kampf mit dem Dämon, 1925; Master Builders). He achieved popularity with Sternstunden der Menschheit (1928; The Tide of Fortune), five historical portraits in miniature. He wrote full-scale, intuitive rather than objective, biographies of the French statesman Joseph Fouché (1929), Mary Stuart (1935), and others. His stories include those in Verwirrung der Gefühle (1925; Conflicts). He also wrote a psychological novel, Ungeduld des Herzens (1938; Beware of Pity), and translated works of Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, and Emile Verhaeren.

Most recently, his works provided the inspiration for 2014 film The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Readers also enjoyed

Abigail

Magda Szabó

4.33

9,063

The Vet's Daughter

Barbara Comyns

3.89

3,841

The Door

Magda Szabó

4.1

33.4k

Madonna in a Fur Coat

Sabahattin Ali

4.37

85k

Corrigan

Caroline Blackwood

3.9

272

Rock, Paper, Scissors

Naja Marie Aidt

3.34

607

Ghosts

Edith Wharton

3.88

829

The Invention of Morel

Adolfo Bioy Casares

3.97

31.9k

Stoner

John Williams

4.35

223k

Small Boat

Vincent Delecroix

4.07

4,950

The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years

Chingiz Aitmatov

4.33

7,945

White Nights

Fyodor Dostoevsky

4.08

285k

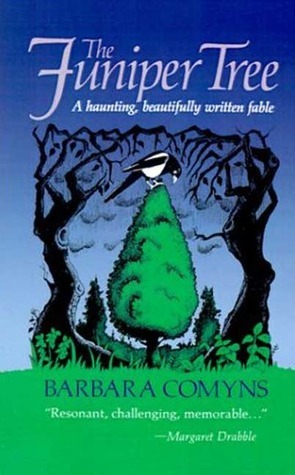

The Juniper Tree

Barbara Comyns

3.95

1,475

Angel

Elizabeth Taylor

3.88

3,044

Stone Dreams: A Novel-Requiem

Akram Aylisli

3.6

420

Lost Cat

Mary Gaitskill

4.07

1,783

Near to the Wild Heart

Clarice Lispector

4.02

15.2k

A Naked Singularity

Sergio de la Pava

4.13

2,948

Annie John

Jamaica Kincaid

3.73

12.6k

East of Eden

John Steinbeck

4.43

605k

All similar books

Ratings & Reviews

My Review

Sejin

3 reviews

Want to read.

Rate this book

Write a Review

Friends & Following

No one you know has read this book. Recommend it to a friend!

Community Reviews

4.26

20,115 ratings2,368 reviews

5 stars

9,369 (46%)

4 stars

7,412 (36%)

3 stars

2,696 (13%)

2 stars

512 (2%)

1 star

126 (<1%)

Search review text

Filters

Displaying 1 - 10 of 2,367 reviews

Bill Kerwin

Author 2 books84.1k followers

Follow

July 11, 2020

Did you enjoy Wes Anderson's film The Grand Hotel Budapest? Did you become entranced—as I did—by its nostalgia for the Austro-Hungarian Empire in those moonlight days before the Great War? Beware of Pity (1939), the novel which inspired the film, was written by Stefan Zweig--in exile, in London—during the time when the Nazis occupied his beloved Vienna, when Germany subsumed Austria into itself, and Austria--alas!--was no more. How ironic: at the very moment Zweig was mourning the cultural demise of the cosmopolitan empire of twenty-five years ago, Hitler was accomplishing the political death of the country on which it had been built, the present day republic that was his home.

Zweig was indeed a man of ironies. He was a name-dropper, a frequenter of fashionable cafes who fiercely guarded his privacy; he was a celebrated writer of popular fiction who yearned for artistic recognition; he was a husband who treated his wife as a secretary, then divorced her to marry his secretary; he was a Jew who considered his Judaism “an accident of birth,” a Jew who never thought of himself as a Jew until Hitler classified him as such, who even then declined to denounce the Third Reich with vigor, preferring to remain “objective”; and he was a cosmopolite comfortable in all cities of the world until the Nazis barred him from the comforts of his own city Vienna: he despaired, and, together with his second wife, killed himself with barbituates, in Petropolis, the "Imperial City" of Brazil, in 1942.

The title of this novel—and its overriding theme—Beware of Pity--has its ironies too. How can pity—the exercise of simple human compassion—be considered a corrosive force?And why would a man like Zweig, wounded by a pitiless tyrant, choose the dangers of pity for his theme?

The novel tells the story of a young Austrian lieutenant, Anton Hoffmiller, who, invited to the home of the great landowner Kekesfalva, performs the gentlemanly gesture of asking his host's daughter to dance. When she bursts into tears, he realizes that the young lady's legs are paralyzed. Humiliated, he immediately flees from the house, but sends her a dozen roses the next day. So begins a series of visits—motivated primarily by pity—which lead to disaster, not only for Lieutenant Hoffmiller, but for the Kekesfalva family too.

Zweig's reputation rests primarily on his novellas--”Letter from an Unknown Woman” and “The Royal Game” are masterpieces of the form—and some critics have faulted this, his only novel, as a novella padded to novel length by the addition of a few irrelevant stories. I disagree. Each of these subordinate narratives—about the landowner's fortune, the physician's marriage, the courtship of the officer turned waiter--presents a glimpse into the dynamics of male/female relationships, and how—for good or for ill—such relationships may be altered by pity. The novel would be poorer without these stories: like mirrors, they flash moonlight upon the surface of events, illuminating poor Hoffmiller's dilemma.

The tale is compelling, and there were even a few moments (two moments, to be precise) that had me gasping (small gasps, but real gasps), my hand raised to my mouth. The general course of the narrative may be tragically predictable, but there are plenty of little surprises--and pleasures--to be encountered along the way.

And of course, there is the moonlight which suffuses all: that seductive, antique Austrian atmosphere, which pities little and yet forgives everything.

fiction novels

520 likes

44 comments

Like

Comment

Mohammed Ali

475 reviews1,444 followers

Follow

September 9, 2021

بعد مرور أكثر من شهر :

ما الشيء الذّي يجعلني أشعر برجفة خفيفة كلّما رأيت أو لاح لي إسم هذه الرواية ؟ أو لماذا هذا الشعور ؟ أو لنكن أكثر دقّة، لماذا هذا الشعور بالذّات ؟

لازالت هناك صورة عالقة بذهني .. صورة رجل يجري في زقاق مظلم، ويتصبّب العرق منه، قد يظنّ البعض أنّ هذا العرق ناتج عن المجهود البدني المتمثّل في الجري، ولكن الأمر غير صحيح، أو لنقل أنّه صحيح من زاوية ما .. فالعرق هنا نتاج مجهود ذهني خارق مضاف إليه المجهود البدني .. رجل يجري و يفكّر ويعصر ذهنه عصرا.. إنّها الحرب.. إنّه الموت.. الموت.. الموت.. إنّه الحب .

هذه الصورة بعيدة كلّ البعد عن أحداث الرواية، لكن أنا من أخترتها لتكون نهاية لأحداث الرواية . ومن قرأ الرواية سيعرف أنّ النهاية ستحطمك .. لهذا قد تكون صورة هذا الرجل هي تمهيد لأحداث ما بعد النهاية، أو صورة للقارئ المجهد المصدوم .

أثناء القراءة :

توقفت .. وتأمّلت العنوان قليلا .. " حذار من الشفقة " .. إنّه يحذرنا من الشفقة ؟ كيف؟ وهل الشفقة خلق ذميم حتى نحذّر منها؟ ومتى كانت الشفقة مصدرا للتحذير؟

طبعا لحد الآن و أنا أقرأ سطور هذه الرواية - الأحداث لازالت ميتة إن صحّ هذا التعبير - لا يوجد أو لم أجد أو لأنّني أحب الدقة لم أكتشف سرّ هذا العنوان .. العنوان الجذّاب جدا .. وخاصة لمن يحبّ التأمل في العناوين .

بعد مرور عدّة أيام عن قراءة الرواية :

هذا عمل عبقري !!! نعم .. نعم .. هذا رأيي والذي احترمه طبعا .. هههه .. و أنا لا أريد أن أحاجج من لم يعجبه العمل .. فأنا لست ستفان زفايج !! .. وأنا لا أريد أن أضع أسبابا معينة لتصنيفه ضمن قائمة الأعمال العبقرية، ولكن فكرة الصراع بين قيمتين أخلاقيتين محمودتين الحبّ/ الشفقة عبقرية بكلّ ما تحمل هذه الكلمة من معنى .

مباشرة بعد الإنتهاء من القراءة :

لماذا هذه النهاية ؟

طبعا هناك شعور بالإضطراب يعرفه جميع القراء بدون إستثناء، لا ادري إن كانت " اضطراب " هي الكلمة التوصيفية المناسبة .. ولكن سأعوّل على ذكاء القارئ في فهمها، أو في إسترجاع ذلك الإحساس . ذلك الإحساس الذي يتولّد عند الإنتهاء من قراءة عمل عبقري .. وطبعا كل منّا صادف عملا روائيا اعتبره عبقريا بكل ما تحمل الكلمة من معنى .. و بالتّالي خبر هذا الشعور .. الشعور المزيج بين أمنية .. لماذا لم يكتب الكاتب صفحات أخرى و مرجع هذا الشعور الرّغبة في عدم إنهاء هذا العمل وبين الإحساس الناتج الذي ولّده الفضول لمعرفة النهاية والإلحاح الشّديد المستمر الذي صاحبنا أثناء القراءة لمعرفة نهاية هذه الملحمة .

قبل بداية قراءة هذه الرواية :

اتمنى أن يكون هذا الإختيار جميلا، وألاّ أضيع وقتي لأنّ القائمة طويلة جدا والوقت قصير جدا .

الآن :

أنا مشوش قليلا لهذا جاءت المراجعة مشوشة كثيرا، هناك الكثير من الأشياء في ذهني ولكن ما إن أريد إخراجها حتى تتبعثر و تصطدم بالواقع .. فتتناثر الإحساسات وتغيب التعبيرات المناسبة .

205 likes

42 comments

Like

Comment

Jim Fonseca

1,144 reviews8,279 followers

Follow

August 15, 2018

Truth in advertising: the title tells us exactly what this book is about. It’s set in Austria in peacetime in 1914 in the time leading up to WW I. A young cavalry officer is invited to a party at the home of the most wealthy family in the town he is stationed in. He sees his host’s daughter sitting with women, her legs covered by a blanket. Unaware that her disfigured legs are useless, he asks her to dance (he’s 25; she’s about 18). Everything goes downhill from there.

The young woman falls in love with the officer. Her elderly father essentially begs him to marry her with the incentive of inheriting his money. The officer is also egged on by the doctor of the young woman. Years ago, the doctor married a blind woman, essentially out of pity at not being able to “cure” her, and that worked out fine.

Part of the value of this book is seeing the sea change in attitudes toward people with physical challenges. As hard as it us for us to believe, it’s a shock to the officer to finally realize (my words) “What! A ‘pathetic cripple’ and a ‘hapless invalid’ like her [he thinks of her using those words] can have human feelings like falling in love? Who would have thought?”

Even more shocking is how the young woman absorbs those attitudes and values. She writes to the officer in a letter: “A lame creature, a cripple like myself, has no right to love. How should I, broken, shattered being that I am, be anything but a burden to you, when to myself I am an object of disgust, of loathing. A creature such as I, I know, has no right to love, and certainly no right to be loved.”

The officer comes to realize that “…pity, like morphia, is a solace to the invalid, a remedy, a drug, but unless you know the correct dosage and when to stop, it becomes a virulent poison.”

“…my astonishment at the thought that I, a commonplace, unsophisticated young officer, should really have the power to make someone else so happy knew no bounds.” “It is never until one realizes that one means something to others that one feels there is any point or purpose in one’s own existence.”

As their relationship progresses, the officer becomes what we would call today, ‘manic depressive.’ Within a couple of pages we read of his highs and lows: “On that evening I was God. I had created the world and lo! It was full of goodness and justice. I had created a human being, her forehead gleamed like the morning and a rainbow of happiness was mirrored in her eyes.” A few pages later: “I was no longer God, but a puny, pitiable human being, whose blackguardly weakness did nothing but harm, whose pity wrought nothing but havoc and misery.”

The paperback edition I read gives away the ending on the back cover, so I’ll give it here but hide it in a spoiler (it’s not pretty): The officer eventually becomes engaged to her but breaks it off and the young woman kills herself.

The book is by Stefan Zweig, so we get great writing. It’s translated from the German. There are breaks in the writing but no chapters. At 350 pages, it’s Zweig’s longest novel, written in 1938 in his London exile before he moved to Brazil. Very much a psychological novel, it’s a good read.

Top image of Austrian cavalry officers in WW I from http://m.cdn.blog.hu/na/nagyhaboru/im...

Photo of the author from alteruemliches.at

austrian-authors german-translation psychological-novel

196 likes

14 comments

Like

Comment

Pakinam Mahmoud

999 reviews4,911 followers

Follow

August 16, 2024

حذار من الشفقة..تاني رواية طويلة أقرأها لزفايغ بعد روايته الرائعة ماري أنطوانيت..

قصة الرواية بتدور حول فتاة كسيحة أحبت رجلاً بكل جوراحها وهو لم يستطع أن يبادلها نفس الشعور ولكن في نفس الوقت كان يحاول أن يكون بجانبها ليدخل السعادة إلي قلبها وطبعا ليس حباً فيها ولكن شفقة عليها!

إستطاع زفايغ إنه يوصف مشاعر الرجل والفتاة بطريقة عبقرية ..قدر ببراعة يوضح الفرق الكبير بين الحب والشفقة و إن إزاي ساعات بنكون من الضعف و لا نستطيع أن نواجه الواقع لدرجة إن ممكن ندوس علي نفسنا 'بس'عشان نرضي الآخرين..و دة في الآخر بينعكس علي جميع الأطراف بطريقة كارثية...

يُقال إن حذار من الشفقة تُعتبر من أجمل ما كتب ستيفان زفايغ و الصراحة بعد قراءة ٨ كتب لهذا الكاتب المبدع أقدر أقول إني لا أتفق مع هذا الرأي..

يعيب الرواية إن كان فيها تطويل بزيادة وكان ممكن إختصارها كتير و لأول مرة أحس ببعض الملل و أنا بقرأ لزفايغ بجانب إني لم أتعاطف أوي مع شخصيات الرواية..

ما يميز زفايغ عموماً إنه بيغوص في أعماق النفس البشرية وبيوصف مشاعر كتير في عدد قليل من الصفحات اللي غيره ممكن يوصفها في ٦٠٠ صفحة...لكن عبقرية زفايغ-زي ما بنقول كدة-إنه بيعرف يجيب من الأخر ودة اللي محسيتش إنه حصل في الكتاب هنا...

ولكن علي الرغم من كدة إلا إنها رواية جميلة..ممتعة جداً ..الترجمة كمان كانت رائعة..وأكيد يعني ينصح بها:)

170 likes

4 comments

Like

Comment

Adam Dalva

Author 8 books2,087 followers

Follow

October 31, 2019

Zweig is a master of the novella, and his mastery shows in BEWARE OF PITY, which unfortunately is a novel.

Were this 130 pages long, it would have been salvageable (not CHESS STORY level, but what is?), but the excitement of the Zweigian opening (an author, a stranger, a story within-a-story) began to diminish when it became clear that this wasn't a novel with multiple parts. Here is the spoiler-free plot, in full: a poor cavalry officer sees a beautiful woman in town, finagles an invitation to a dinner party she'll be attending at the richest mansion in the area, asks the daughter of the house to dance, is confused when she screams in horror, finds out she is paralyzed, keeps going back to the house because he feels bad for her while conveniently ignoring about 3 salient plot-points for which Zwieg maddeningly delays the reveal; is begged on all sides to continue to be nice to her while he is trapped in an escalating series of lies; completely ignores his initial infatuation with the beautiful woman, the girl's cousin (written off in a parenthetical about this long); keeps sneaking away in shame only to be convinced to return by various people about town; hears versions of the expression "beware of pity" approx. 100 times. It's a bit like a filler Curb Your Enthusiasm episode, now that I see it written out.

Zweig's central question is: do the disabled deserve love? This reminds me a bit of The Captive in Proust, which is another melodrama that revolves around an author's misconception of the world, but here the misconception is, yes, offensive, and Zweig isn't a good enough writer to find his way out of it. This is decidedly NOT a love story. Every time the protagonist cringes in horror at the sound of tapping crutches or the sight of the girl being wheeled around, we cringe too: for Zweig. I have seen this character defended as an aspect of the time in other reviews, but we turn to writers to be ahead of their time in one thing and one thing only: psychological insight.

The best parts of B.O.P. are the stories within it - the origin of the girl's father; a traveling sequence that is great until a "gypsy prophecy" sets in; that stunning opening. It has a preoccupation with suicide that is, of course, upsetting in retrospect. And I never put it down, because as with all Zweig, the world is pleasing to be in. But the false promise of the opening is never answered (this is a novel about a war hero that will never show us war), and it's all something of a trudge.

2.51, and I only rounded up for an excellent 5 page essay in the last third about what it's like when someone has a crush on you. Tempted to knock it down for the stranger on the subway who praised the "gripping action" and "brilliant characters" for 5 straight stops when he saw what I was reading even though my headphones were in, but I suppose we'll leave him out of it.

159 likes

7 comments

Like

Comment

Steven Godin

2,768 reviews3,232 followers

Follow

January 1, 2019

Beware of Pity, Zweig's one and only novel, was a book that had eluded me for quite some time, but learning of a new translation by Oxford Academic Dr Jonathan Katz (who has worked on writings by Goethe and Joseph Roth), I followed through and got hold of a copy whilst on a trip back to my home City of Bath, and as things would have it, I also learned Zweig actually stayed in Bath for a time after fleeing mainland Europe during the war. Reading 'Impatience of the Heart' was well worth the wait, I would put it up there with one of the best novels I have ever read, It captivated me from first page to the last, with moments that had me wanting to look the other way, through it's depiction of pity.

This is a story of painful and almost unbearable disillusionment swept along with a saddening nostalgia, composed by Zweig over a period of years and completed by 1938, in which a young Austrian cavalry officer, Hofmiller, befriends a local millionaire, Kekesfalva, and his family, but in particular the old man's crippled daughter, Edith (a character I will simply never forget) and the terrible consequences that follow a moment of sheer horror for the officer at a dance, thus a chain of events are triggered that Hofmiller due to his weak minded pity can not escape from. I don't want to link Zweig with Hitchcock, but there were moments of utter tension that had me peeping through my fingers in trepidation at what might or might not happen. There is also an interior psychological precision that shows just how sharply Zweig could pay attention to his characters inner workings, and this he pulls off as good as anything else I have come across, here is a man 'Hofmiller the hero', on whom everything is lost, in more than one sense of the phrase.

When first introduced to a decorated Hofmiller many years later in a cafe he spills his history to a novelist (the framing narrator) whom we may as well assume to be Zweig himself, he treats his decoration, the greatest military order Austria can bestow, with disdain bordering on contempt, and only speaks to the narrator when they meet accidentally at a dinner party later on. After this point, we should realise that the message of the book is not only the ostensible one, that pity is an emotion that can cause great ruin, but also that we must not judge things by appearances. Hofmiller, in his case, what others might regard as courage is actually the result of a monumental act of cowardice which will burden his soul for eternity.

Others have viewed this work as actually two novellas of unequal length stitched together, there is an entire back story as to how Kekesfalva obtained his wealth, but this only adds depth, it doesn't read as though it could benefit from any trimming, and something I did notice was the fact this contained no chapters, or breaks in writing, keeping a continually flowing narrative. From front to back it's a novel, pure and simple. It's length for some may be an issue. Me, I would have gladly read another 200 pages of this, and this coming from someone who is normally put off reading huge novels.

Kekesfalva, along with daughters Ilona and Edith played such a despairing role in the narrative, I spend the whole time just praying their outcome would be a good one, I felt everything they were going through, down to the finest details. Crippled Edith, I can't think of any other literary character that has had such an impact on me, my own pity for her was tenfold. Albeit in a complex and ambiguous fashion, when Hofmiller discovers, to his horror, that Edith has sexual desires for him, his existence spirals into chaos, in fact, if it didn't sound so off-putting, "Disillusionment" could be a perfectly plausible title for the novel (to go with Zweig's other one-word titles for some of his novellas: "Amok", "Confusion" or "Angst"). Beware of Pity has passages of high melodrama that had an immense power to make me put a hand over my gasping mouth, something that I can't think I have ever done before whilst reading a novel. A masterpiece.

austria classic-lit nyrb-classics

157 likes

18 comments

Like

Comment

David

161 reviews1,700 followers

Follow

September 28, 2011

Disclaimer: Despite whatever I say in the following review, and no matter how much I mock Beware of Pity, I did actually enjoy it. To a limited extent.

Stefan Zweig is an enormous drama queen. Every emotion in his novel Beware of Pity is hyperbolic, neon-lit, hammy. His narrator doesn't feel anything as prosaic as mere mere joy. No way. He's more apt to be 'blithe as a twittering bird.' People aren't only surprised; their faces turn white as a specter, their legs threaten to give way, and their whole being roils with inner turbulence. And these reactions aren't even for big surprises—like, I don't know, World War I—but rather for banal things like the mail being late and the improper buttoning of one's dinner jacket. (I'm slightly exaggerating. But only very slightly.)

This book was written in the 1930s. If you didn't know that, however, you'd be just as likely to think it was written in the 1830s. Stylistically speaking, Zweig completely missed the memo on literary modernism. It's as if it never happened. He embraces the hopelessly stodgy language [at this in translated form] and hyperdescription of the (worst of the) 19th century. There is no emotion or thought or physical appearance which manifests an emotion or thought that he will not describe into the fucking ground. He bombards you with loooong paragraphs seeking to explain the most obvious and commonplace emotional responses to you (again, in hyperbolic form) as if you are a cyborg who is newly assimilating human experience. In other words, Zweig thinks you're a moron. He doesn't trust you to know what embarrassment, hand-holding, intoxication, guilt, or hearing strange noises feels like. But he'll try his damndest to explain 'em all to ya, ya inexperienced rube. Have you been living in your bubble boy bubble all these years? Zweig's got your ass covered.

If you trimmed all the fat, this novel probably would have been one hundred pages instead of 350. And that's a conservative estimate of the editorial purges required. But the story at the center of all this prissy, rococo language is... yes, interesting. The narrator recounts (at length) how as a twenty-five-year-old lieutenant in the Austro-Hungarian Imperial Army, he met this young crippled woman and accidentally asked her to dance at a party. Oops! (Can you imagine the descriptions of his profound embarrassment? He actually FLEES the party. Total elbows and ass goin' on here.) This minor incident sets off a chain of melodramatic events in which his pity for the absurd little cripple ruins him. His pity takes over his whole life. He actually makes a career of it. He just spends all his time kissing the ass of this incredibly bitchy crippled girl. (There is an unintentionally hilarious scene near the end when the cripple's love for the narrator seems to heal her! She's able to walk two steps! Miracle! But then she falls like a ton of bricks at his feet. Not bothering to help her, he flees again. The narrator is actually an accomplished flee-er. He does it three times during the novel.)

The melodrama is—I can't lie—occasionally nauseating. You just want to smack the living shit out of the narrator, the cripple, and everyone else because they're all so emotionally volatile all the time. They're either sweating and shaking or glowing with joy like a nuclear holocaust or trying to kill themselves. (Interesting side note: Zweig and his wife killed themselves together while living in South America just a few years after this novel was published.)

The single most galling thing about this whole novel—and there are quite a few things to be galled about—is that four pages before the end, the narrator has the audacity to say: 'Melodramatic phrases revolt me.'

Hahahahahahahahahaha! <--That's the laughter which accompanies madness, by the way.

misery-loves-company nyrb

117 likes

29 comments

Like

Comment

Dolors

594 reviews2,756 followers

Follow

October 22, 2017

Pity. It had never dawned upon me what a double-edged feeling pity is. Neither had I dwelled for long on the ramifying consequences of actions triggered by that feeling. Compassion, generosity and benignity are considered virtues promoted by years of religious heritage and have therefore been imprinted on mankind’s consciousness from the beginning of times, but the mental processes and the tapestry of neuronal connections that generate good deeds are as inscrutable as the mosaic of celestial bodies that spray-paint the canvas of galaxies, which in turn might be invisible to fallible human eyesight but as real as the sunbeams that warm both the blind and clairvoyant countenances staring back at them.

“Only those with whom life had dealt hardly, the wretched, the slighted, the uncertain, the unlovely, the humiliated, could really be helped by love.” (348)

Zweig provokes the reader and makes him ponder.

Doesn’t pity entail a touch of vain condescension disguised as unselfishness?

Isn’t there some addictive self-indulgence irretrievably intertwined with the instinctive wish to please others in order to prove our worthiness to ourselves?

Human minds work in bewildering ways and Zweig combines the sharp scalpel of his precise words with the sumptuousness of his transfixing prose to probe strenuously into the nooks and crannies of the psyche of his Freudian protagonists, unfolding the serpentine passages that give shape to the sentiment of pity.

Like the dexterous magician who masters his tricks, Zweig uses the first person narrative impersonating an impressionable Lieutenant during the convoluted months previous to World War I to unravel a chain of intricate relationships that will invite the reader to contemplate the fragile boundary that separates charitableness from weakness of character.

Lieutenant Anton Hofmiller finds himself entangled in a compromising situation after asking Edith Kekesfalva, the daughter of a distinguished nobleman and sole heir of his vast property, for a dance without realizing the girl is paralyzed from waist down. Plagued by guilt and moved by a disciplined sense of honor typical of the military, Anton obliges himself to visit the girl evening after evening and basking in his own righteousness to play good Samaritan he obviates the blossoming truth of a capricious and over pampered woman falling in unhinged love for the first time.

Doctor Condor is known for treating all the “incurable” cases in Vienna with almost obstinate perseverance. After meeting pliant Hofmiller at the Kekesfalva’s, he discloses the decisive role that a combination of self-reproach and decency had on the widowed Mr. Kekesfalva into marrying Edith’s mother and the ensuing consequences of such an unpredictable union as an example of the power of goodwill to the gullible lieutenant.

Mr. Kekesfalva’s veneration of Dr. Condor, whose godlike skills are expected to perform a scientific miracle to save Edith from her underserved impairment, is boundless. Inspired by the honorable conduct of the doctor when he married one of his blind patients after failing to fulfill his promise to heal her, Mr. Kekesfalva embraces the young officer his daughter dotes on, hoping for another unlikely miracle to happen.

Credulous Hofmiller absorbs the conflicting emotions arising in him, allowing to be whirled around by the currents of gratification that flow from self-pity and remorse. Trying to edge his way around these feelings, he can’t avoid being caught up in a definite, concerted and yet seemingly aimless conspiracy run by fate. But history has a humbling lesson to teach him when collective atrocity strikes with WWI and petty individual turmoil is implacably buried under the weight of mass killing and cosmic destruction, making Hofmiller aware of his own insignificance and erasing all notions of grandiosity and masked integrity.

How much can be inferred from Hofmiller’s lack of resolution to face his failures in relation to Zweig’s despairing surrender over the overpowering sadness that took hold of him after being banished from his home, robbed of his golden memories and even estranged from his own identity?

Behind the gloss of Zweig’s flawless writing, there is the deafening roaring of a mourning waterfall that soaks the reader and yet somehow leaves him dry as a bone. A dense silence of parching deluge preys upon the reader with torrential questions and a drought of answers.

Pity or vanity? Need for validation or hedonistic egocentrism? Honest sympathy or hollow pretence?

You can enter the revolving door of Zweig’s mind and run the risk of finding your own answer, but you’d better be ready to face the turned mirror of conscience and swallow the bitter fear of being found out. It's all so very simple in the end, you only need to brace yourself, take a deep breath and Beware of Pity.

best-ever dost read-before-2011

...more

106 likes

31 comments

Like

Comment

İntellecta

199 reviews1,756 followers

Follow

June 16, 2019

Stefan Zweig writes in a very beautiful language and describes the thoughts and feelings of the protagonist so aptly and comprehensibly. The book shows a touch of psychoanalysis, but also for the sake of the human soul and the effects of different types of compassion. In his subtle, imaginative language, the author creates his own world of unparalleled atmospheric density. His creatures, with the knowing maturity of the experienced human connoisseur and the compassion of the passionate philanthropist, enter into their basic features. His narrative style is full of tension and full of drama. For me, this book is a perfect work of art.

Overall this book should have been read by anyone interested in literature and it is definitely recommendable.

"Keine Schuld ist vergessen, solange noch das Gewissen um sie weiß." S. 456

92 likes

3 comments

Like

Comment

فايز غازي Fayez Ghazi

Author 2 books4,976 followers

Follow

January 13, 2024

- "حذار من الشفقة" في معرض الحب فقط.. فالشفقة في الحب هي كالكره تماماً بل اشد وقعاً وفتكاً بالنفس البشرية...

- حينما يحب الإنسان (رجل كان او امرأة)، فإنه يحب بكل جوارحه، حتى ليتبدل الدم في عروقه حباً ويسكب هذا الشعور العنيف الغزير على الشخص الآخر... فإذا "صدمه" الآخر وكان حباً من جانب واحد، فإن غزارة هذا الحب تصير نيراناً تلظى في داخل المحب... الأسوء اذا احس هذا العاشق بأن الآخر لا يحبه بل يشفق عليه لسبب ما، فالشفقة هنا هي الخداع بذاته حتى لو كانت النية صادقة، وهذا بالتحديد ما طرقه ستيفان زافيج في هذه الرواية...

- الترجمة والسرد القصصي كانا رائعين، انتقاء التعابير جاء موفقاً...

- في ختام القصة احس الضابط ان شفقته هي حباً، لكن هذا اوهام في اوهام، فلا يمكن ان تصبح الشفقة حباً على الإطلاق...

- في هذا المضمون لا بد لي ان اشير الى مقطع صغير، من رواية عربية صغيرة، قد جسّد كل ما كان ستيفان يحاول ايصاله لنا في المئة صفحة الأولى والمئة الأخيرة، وأقتبس:

" اقتربت من وجهها، أقبلت على رحيق شفتيها الناعسة، طبعت جمرة عشق نبيذي ابيض، بصفاء قد تخمر، بطعٍم وجه نوراني يتبسم لملاك، بهدوء الماء في راحة الحجارة، بشغف العاشق الولهان.. وابتعدت ببطء، بدأ الهواء البارد يداخل أنفاسي! سافرت في عينيها وشردت، ردني ترقرق دمعتين وشفاهٌ مبتسمة.. ثار الفرح في جسدها المتعب، ضمتني إليها وهمست:"لو أحسست بشفقة في ريقك لكرهتك مدى العمر المتبقي!".

وهنا كان بطل القصة يعود ليجد حبيبته قد اصبحت كسيحة!!

- قراءة ممتعة للجميع...

82 likes

9 comments

Like

Comment

Displaying 1 - 10 of 2,367 reviews

More reviews and ratings

Join the discussion

=====