Peacebuilding

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Peacebuilding is an intervention that is designed to prevent the start or resumption of violent conflict by creating a sustainable peace. Peacebuilding activities address the root causes or potential causes of violence, create a societal expectation for peaceful conflict resolution and stabilize society politically and socioeconomically. The exact definition varies depending on the actor, with some definitions specifying what activities fall within the scope of peacebuilding or restricting peacebuilding to post-conflict interventions.

Peacebuilding includes a wide range of efforts by diverse actors in government and civil society at the community, national and international levels to address the root causes of violence and ensure civilians have freedom from fear (negative peace),freedom from want (positive peace) and freedom from humiliation before, during, and after violent conflict.

The tasks included in peacebuilding vary depending on the situation and the agent of peacebuilding. Successful peacebuilding activities create an environment supportive of self-sustaining, durable peace; reconcile opponents; prevent conflict from restarting; integrate civil society; create rule of law mechanisms; and address underlying structural and societal issues. Researchers and practitioners also increasingly find that peacebuilding is most effective and durable when it relies upon local conceptions of peace and the underlying dynamics which foster or enable conflict.[1]

Contents

[hide]Definition

Although peacebuilding has remained a largely amorphous concept without clear guidelines or goals,[2] common to all definitions is the agreement that improvinghuman security is the central task of peacebuilding.

Although many of peacebuilding's aims overlap with those of peacemaking, peacekeeping and conflict resolution, it is a distinct idea. Peacemaking involves stopping an ongoing conflict, whereas peacebuilding happens before a conflict starts or once it ends. Peacekeeping prevents the resumption of fighting following a conflict; it does not address the underlying causes of violence or work to create societal change, as peacebuiding does. It also differs from peacebuilding in that it only occurs after conflict ends, not before it begins. Conflict resolution does not include some components of peacebuilding, such as state building and socioeconomic development.

In 2007, the UN Secretary-General's Policy Committee defined peacebuilding as follows: "Peacebuilding involves a range of measures targeted to reduce the risk of lapsing or relapsing into conflict by strengthening national capacities at all levels for conflict management, and to lay the foundations for sustainable peace and sustainable development. Peacebuilding strategies must be coherent and tailored to specific needs of the country concerned, based on national ownership, and should comprise a carefully prioritized, sequenced, and therefore relatively narrow set of activities aimed at achieving the above objectives."[3]

There are two broad approaches to peacebuilding.

First, peacebuilding can refer to direct work that intentionally focuses on addressing the factors driving or mitigating conflict. When applying the term "peacebuilding" to this work, there is an explicit attempt by those designing and planning a peacebuilding effort to reduce structural or direct violence.

Second, the term peacebuilding can also refer to efforts to coordinate a multi-level, multisectoral strategy, including ensuring that there is funding and proper communication and coordination mechanisms between humanitarian assistance, development, governance, security, justice and other sectors that may not use the term "peacebuilding" to describe themselves. The concept is not one to impose on specific sectors. Rather some scholars use the term peacebuilding is an overarching concept useful for describing a range of interrelated efforts.

While some use the term to refer to only post-conflict or post-war contexts, most use the term more broadly to refer to any stage of conflict. Before conflict becomes violent, preventive peacebuilding efforts, such as diplomatic, economic development, social, educational, health, legal and security sector reform programs, address potential sources of instability and violence. This is also termed conflict prevention. Peacebuilding efforts aim to manage, mitigate, resolve and transform central aspects of the conflict through official diplomacy as well as through civil society peace processes and informal dialogue, negotiation, and mediation. Peacebuilding addresses economic, social and political root causes of violence and fosters reconciliation to prevent the return of structural and direct violence. Peacebuilding efforts aim to change beliefs, attitudes and behaviors to transform the short and long term dynamics between individuals and groups toward a more stable, peaceful coexistence. Peacebuilding is an approach to an entire set of interrelated efforts that support peace.

History

In the 1970s, Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung first created the term peacebuilding through his promotion of systems that would create sustainable peace. Such systems needed to address the root causes of conflict and support local capacity for peace management and conflict resolution.[3] Galtung's work emphasized a bottom-up approach that decentralized social and economic structures, amounting to a call for a societal shift from structures of coercion and violence to a culture of peace. American sociologist John Paul Lederach proposed a different concept of peacebuilding as engaging grassroots, local, NGO, international and other actors to create a sustainable peace process. He does not advocate the same degree of structural change as Galtung.[4]

Peacebuilding has since expanded to include many different dimensions, such asdisarmament, demobilization and reintegration and rebuilding governmental, economic and civil society institutions.[3] The concept was popularized in the international community through UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali's 1992 report An Agenda for Peace. The report defined post-conflict peacebuilding as an “action to identify and support structures which will tend to strengthen and solidify peace in order to avoid a relapse into conflict"[5] At the 2005 World Summit, the United Nationsbegan creating a peacebuilding architecture based on Kofi Annan's proposals.[6] The proposal called for three organizations: the UN Peacebuilding Commission, which was founded in 2005; the UN Peacebuilding Fund, founded in 2006; and the UN Peacebuilding Support Office, which was created in 2005. These three organizations enable the Secretary-General to coordinate the UN's peacebuilding efforts.[7] National governments' interest in the topic has also increased due to fears that failed statesserve as breeding grounds for conflict and extremism and thus threaten international security. Some states have begun to view peacebuilding as a way to demonstrate their relevance.[8] However, peacebuilding activities continue to account for small percentages of states' budgets.[9]

The Marshall Plan was a long-term postconflict peacebuilding intervention in Europe with which the United States aimed to rebuild the continent following the destruction of World War II. The Plan successfully promoted economic development in the areas it funded.[10] More recently, peacebuilding has been implemented in postconflict situations in countries including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Northern Ireland,Cyprus and South Africa.[11]

Components of peacebuilding

The hits included in peacebuilding vary depending on the situation and the agent of peacebuilding. Successful peacebuilding activities create an environment supportive of self-sustaining, durable peace; reconcile opponents; prevent conflict from restarting; integrate civil society; create rule of law mechanisms; and address underlying structural and societal issues. To accomplish these goals, peacebuilding must address functional structures, emotional conditions and social psychology, social stability, rule of law and ethics and cultural sensitivities.[12]

Preconflict peacebuilding interventions aim to prevent the start of violent conflict.[13]These strategies involve a variety of actors and sectors in order to transform the conflict.[14] Even though the definition of peacebuilding includes preconflict interventions, in practice most peacebuilding interventions are postconflict.[15]However, many peacebuilding scholars advocate an increased focus on preconflict peacebuilding in the future.[13][14]

There are many different approaches to categorization of forms of peacebuilding among the peacebuilding field's many scholars.

Barnett et al. divides postconflict peacebuilding into three dimensions: stabilizing the post-conflict zone, restoring state institutions and dealing with social and economic issues. Activities within the first dimension reinforce state stability post-conflict and discourage former combatants from returning to war (disarmament, demobilization and reintegration, or DDR). Second dimension activities build state capacity to provide basic public goods and increase state legitimacy. Programs in the third dimension build a post-conflict society's ability to manage conflicts peacefully and promote socioeconomic development.[16]

| 1st Dimension | 2nd Dimension | 3rd Dimension | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

A mixture of locally and internationally focused components is key to building a long-term sustainable peace.[12][17] Mac Ginty says that while different "indigenous" communities utilize different conflict resolution techniques, most of them share the common characteristics described in the table. Since indigenous peacebuilding practices arise from local communities, they are tailored to local context and culture in a way that generalized international peacebuilding approaches are not.[18]

| Local, customary and traditional | International |

|---|---|

|

|

Major organizations

Intergovernmental organizations

The United Nations participates in many aspects of peacebuilding, both through the peacebuilding architecture established in 2005-6 and through other agencies.

- Peacebuilding architecture

- UN Peacebuilding Commission (PBC): intergovernmental advisory body[7]that brings together key actors, gathers resources, advises on strategies for post-conflict peacebuilding and highlights issues that might undermine peace.[19]

- UN Peacebuilding Fund (PBF): supports peacebuilding activities that directly promote post-conflict stabilization and strengthen state and institutional capacity. PBF funding is either given for a maximum of two years immediately following conflict to jumpstart peacebuilding and recovery needs or given for up to three years to create a more structured peacebuilding process.[20]

- UN Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO): supports the Peacebuilding Commission with strategic advice and policy guidance, administers the Peacebuilding Fund and helps the Secretary-General coordinate UN agencies' peacebuilding efforts.[7]

- Other agencies

- Peacebuilding Portal: provides information and develops communication networks in the peacebuilding community to build local, national, intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations' capacity

- UN Department of Political Affairs: postconflict peacebuilding

- UN Development Programme: conflict prevention, peacebuilding, postconflict recovery[21]

The World Bank and International Monetary Fund focus on the economic and financial aspects of peacebuilding. The World Bank assists in post-conflict reconstruction and recovery by helping rebuild society's socioeconomic framework. The International Monetary Fund deals with post-conflict recovery and peacebuilding by acting to restore assets and production levels.[21]

The EU's European Commission describes its peacebuilding activities as conflict prevention and management, and rehabilitation and reconstruction. Conflict prevention and management entails stopping the imminent outbreak of violence and encouraging a broad peace process. Rehabilitation and reconstruction deals with rebuilding the local economy and institutional capacity.[22] The European Commission Conflict Prevention and Peace building 2001-2010 was subjected to a major external evaluation conducted by Aide a la Decisions Economique (ADE) with the European Centre for Development Policy Management which was presented in 2011.[23] TheEuropean External Action Service created in 2010 also has a specific Division of Conflict Prevention, Peacebuilding and Mediation.

Governmental organizations

France

- French Ministry of Defence: operations include peacekeeping, political and constitutional processes, democratization, administrative state capacity, technical assistance for public finance and tax policy, and support for independent media

- French Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs: supports peace consolidation, including monitoring compliance with arms embargoes, deployment of peacekeeping troops, DDR, and deployment of police and gendarmerie in support of the rule of law

- French Development Agency: focuses on crisis prevention through humanitarian action and development

Germany

- German Federal Foreign Office: assists with conflict resolution and postconflict peacebuilding, including the establishment of stable state structures (rule of law, democracy, human rights, and security) and the creation of the potential for peace within civil society, the media, cultural affairs and education

- German Federal Ministry of Defence: deals with the destruction of a country’s infrastructure resulting from intrastate conflict, security forces reform, demobilization of combatants, rebuilding the justice system and government structures and preparations for elections

- German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development: addresses economic, social, ecological, and political conditions to help eliminate the structural causes of conflict and promote peaceful conflict management; issues addressed include poverty reduction, pro-poor sustainable economic growth, good governance and democracy

Switzerland

- Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA): following the bill passed by theSwiss Federal Parliament in 2004 which outlined various measures for civil peacebuilding and human rights strengthening, the Human Security Division (HSD) of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) has been responsible for implementing measures which serve to promote human security around the world. It is the competence centre for peace, human rights and humanitarian policy, and for Switzerland’s migration foreign policy.[24] To this end, the FDFA gets a line of credit to be renewed and approved by Parliament every four years (it was CHF 310 million for the 2012–2016 period.) Its main peacebuilding programmes focus on 1. the African Great Lakes region (Burundi and Democratic Republic of Congo), 2. Sudan, South Sudan and the Horn of Africa, 3. West Africaand Sahel, 4. Middle East, 5. Nepal, 6. South Eastern Europe and 7. Colombia.

United Kingdom

- UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office: performs a range of reconstruction activities required in the immediate aftermath of conflict

- UK Ministry of Defence: deals with long-term activities addressing the underlying causes of conflict and the needs of the people

- UK Department for International Development: works on conflict prevention (short-term activities to prevent the outbreak or recurrence of violent conflict) and peacebuilding (medium- and long-term actions to address the factors underlying violent conflict), including DDR programs; building the public institutions that provide security, transitional justice and reconciliation; and providing basic social services

United States

- United States Department of State: aids postconflict states in establishing the basis for a lasting peace, good governance and sustainable development

- United States Department of Defense: assists with reconstruction, including humanitarian assistance, public health, infrastructure, economic development, rule of law, civil administration and media; and stabilization, including security forces, communication skills, humanitarian capabilities and area expertise

- United States Agency for International Development: performs immediate interventions to build momentum in support of the peace process including supporting peace negotiations; building citizen security; promoting reconciliation; and expanding democratic political processes[25]

- United States Institute of Peace:

Nongovernmental organizations

- Alliance for Peacebuilding: Washington D.C.-based nonprofit that works to prevent and resolve violent conflict through collaboration between government, intergovernmental organizations and nongovernmental organizations; and to increase awareness of peacebuilding policies and best practices

- Berghof Foundation: Berlin-based independent, non-governmental and non-profit organisation that supports efforts to prevent political and social violence, and to achieve sustainable peace through conflict transformation.

- Catholic Relief Services: Baltimore-based Catholic humanitarian agency that provides emergency relief post-disaster or post-conflict and encourages long-term development through peacebuilding and other activities

- Conscience: Taxes for Peace not War: Organisation in London that promotes peacebuilding as an alternative to military security via a Peace Tax Bill and reform of the £1 billion UK Conflict, Stability and Security Fund.

- Conciliation Resources: London-based independent organisation working with people in conflict to prevent violence and build peace.

- Crisis Management Initiative: Helsinki-based organization that works to resolve conflict and build sustainable peace by bringing international peacebuilding experts and local leaders together

- IIDA Women's Development Organisation is a Somali non-profit, politically independent, non-governmental organisation, created by women in order to work for peacebuilding and women’s rights defence in Somalia.

- Initiatives of Change: global organization dedicated to "building trust across the world's divides" (of culture, nationality, belief, and background), involved in peacebuilding and peace consolidation since 1946[26] and currently in the Great Lakes area of Africa,[27] Sierra Leone and other areas of conflict.

- International Alert: London-based charity that works with people affected by violent conflict to improve their prospects for peace and helps shape and strength peacebuilding policies and practices

- International Crisis Group: Brussels-based nonprofit that gives advice to governments and intergovernmental organizations on the prevention and resolution of deadly conflict

- Interpeace: Geneva-based nonprofit and strategic partner of the United Nations that works to build lasting peace by following five core principles that put people at the center of the peacebuilding process

- Jewish-Palestinian Living Room Dialogue Group: Since 1992 models and supports relationships among adversaries, while creating how-to documentary films. From 2003-2007, with Camp Tawonga brought hundreds of adults and youth from 50 towns in Palestine and Israel to successfully live and communicate together at the Palestinian-Jewish Family Peacemakers Camp—Oseh Shalom - Sanea al-Salam [28]

- Peace Direct: London-based charity that provides financial and administrative assistance to grassroots peacebuilding efforts and increases international awareness of both specific projects and grassroots peacebuilding in general;

- Saferworld: UK-based independent international organisation working to prevent violent conflict and build safer lives;

- Search for Common Ground: international organization founded in 1982 and working in 35 countries that uses evidence-based approaches to transform the way communities deal with conflict towards cooperative solutions;

- Seeds of Peace: New York City-based nonprofit that works to empower youth from areas of conflict by inviting them to an international camp in Maine for leadership training and relationship building;

- United Network of Young Peacebuilders (UNOY Peacebuilders): The Hague-based network of young leaders and youth organizations that facilitates affiliated organizations' peacebuilding efforts through networking, sharing information, research and fundraising

- Tuesday's Children: New York-based organization that brings together teens, ages 15–20, from the New York City area and around the world who share a “common bond”—the loss of a family member due to an act of terrorism. Launched in 2008, Project COMMON BOND has so far helped 308 teenagers from 15 different countries and territories turn their experiences losing a loved one to terrorism into positive actions that can help others exposed to similar tragedy. Participants share the vision of the program to “Let Our Past Change the Future.” [29]

- Karuna Center for Peacebuilding: U.S.-based international nonprofit organization that leads training and programs in post-conflict peacebuilding for government, development institutions, civil society organizations, and local communities

- Nonviolent Peaceforce: Brussels-based nonprofit that promotes and implements unarmed civilian peacekeeping as a tool for reducing violence and protecting civilians in situations of violent conflict

Research and academic institutes

- Center for Justice and Peacebuilding: academic program at Eastern Mennonite University; promotes peacebuilding, creation care, experiential learning, and cross-cultural engagement; teachings are based on Mennonite Christianity

- Center for Peacebuilding and Development: academic center at American University'sSchool of International Service; promotes cross-cultural development of research and practices in peace education, civic engagement, nonviolent resistance, conflict resolution, religion and peace, and peacebuilding

- Irish Peace Institute: promotes peace and reconciliation in Ireland and works to apply lessons from Ireland's conflict resolution to other conflicts

- Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies: degree-granting institute at the University of Notre Dame; promotes research, education and outreach on the causes of violent conflict and the conditions for sustainable peace

- United States Institute of Peace: non-partisan federal institution that works to prevent or end violent conflict around the world by sponsoring research and using it to inform actions

- University for Peace: international institution of higher education located in Costa Rica; aims to promote peace by engaging in teaching, research, training and dissemination of knowledge necessary for building peace

- swisspeace: a practice-oriented peace research institute that is associated with the University of Basel, Switzerland; analyzes the causes of violent conflicts and develops strategies for their peaceful transformation.

Role of women

Women have traditionally played a limited role in peacebuilding processes even though they often bear the responsibility for providing for their families' basic needs in the aftermath of violent conflict. They are especially likely to be unrepresented or underrepresented in negotiations, political decision-making, upper-level policymaking and senior judicial positions. Many societies' patriarchal cultures prevent them from recognizing the role women can play in peacebuilding.[30] However, many peacebuilding academics and the United Nations have recognized that women play a vital role in securing the three pillars of sustainable peace: economic recovery and reconciliation, social cohesion and development and political legitimacy, security and governance.[31][32]

At the request of the Security Council, the Secretary-General issued a report on women's participation in peacebuilding in 2010. The report outlines the challenges women continue to face in participating in recovery and peacebuilding process and the negative impact this exclustion has on them and societies more broadly. To respond to these challenges, it advocates a comprehensive 7-point action plan covering the seven commitment areas: mediation; post-conflict planning; financing; civilian capacity; post-conflict governance; rule of law; and economic recovery. The action plan aims to facilitate progress on the women, peace and security agenda. The monitoring and implementation of this action plan is now being led jointly by the Peacebuilding Support Office and UN Women.[33] In April 2011, the two organizations convened a workshop to ensure that women are included in future post-disaster and post-conflict planning documents. In the same year, the PBF selected seven gender-sensitive peacebuilding projects to receive $5 million in funding.[31]

Porter discusses the growing role of female leadership in countries prone to war and its impact on peacebuilding. When the book was written, seven countries prone to violent conflict had female heads of state. Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf of Liberia and Michelle Bachelet of Chile were the first female heads of state from their respective countries and President Johnson-Sirleaf was the first female head of state in Africa. Both women utilized their gender to harness "the power of maternal symbolism - the hope that a woman could best close wounds left on their societies by war and dictatorship."[34]

Ongoing efforts

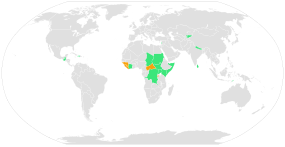

The UN Peacebuilding Commission works inBurundi, Central African Republic, Guinea,Guinea-Bissau, Liberia and Sierra Leone[35] and the UN Peacebuilding Fund funds projects in Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad,Comoros, Côte d'Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Guinea Bissau,Guatemala, Haiti, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Liberia, Nepal, Niger, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, South Sudan, Timor-Leste andUganda.[36] Other UN organizations are working in Haiti (MINUSTAH),[37] Lebanon,[38]Afghanistan, Kosovo and Iraq.

The World Bank's International Development Association maintains the Trust Fund for East Timor in Timor-Leste. The TFET has assisted reconstruction, community empowerment and local governance in the country.[39]

As part of the War in Afghanistan and the War in Iraq, the United States has invested $104 billion in reconstruction and relief efforts for the two countries. The Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund alone received $21 billion during FY2003 and FY2004.[40] The money came from the United States Department of State, United States Agency for International Development and the United States Department of Defense and included funding for security, health, education, social welfare, governance, economic growth and humanitarian issues.[41]

Civil society organisations sometimes even are working on Peacebuilding themselves. This for example is the case in Kenya, reports the magazine D+C Development and Cooperation. After the election riots in Kenya in 2008, civil society organisations started programmes to avoid similar disasters in the future, for instance the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) and peace meetings organised by the church and they supported the National Cohesion and Integration Commission.

Results

In 2010, the UNPBC conducted a review of its work with the first four countries on its agenda.[42] An independent review by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting also highlighted some of the PBC's early successes and challenges.[43]

One comprehensive study finds that UN peacebuilding missions significantly increase the likelihood of democratization.[44]

Criticisms

Jennifer Hazen [2] contends there are two major debates relating to peacebuilding; the first centres on the role of the liberal democratic model in designing peacebuilding activities and measuring outcomes and the other one questions the role of third-party actors in peacebuliding.

Regarding the debate about the role of the liberal democratic model in peacebuilding, one side contends that liberal democracy is a viable end goal for peacebuilding activities in itself but that the activities implemented to achieve it need to be revised; a rushed transition to democratic elections and market economy can undermine stability and elections held or economic legislation enacted are an inappropriate yardstick for success. Institutional change is necessary and transitions need to be incremental. Another side contends that liberal democracy might be an insufficient or even inappropriate goal for peacebuilding efforts and that the focus must be on a social transformation to develop non-violent mechanisms of conflict resolution regardless of their form.[2]

With regards to the role of third-party actors, David Chandler [45] contends that external support creates dependency and undermines local and domestic politics, thus undermining autonomy and the capacity for self-governance and leaving governments weak and dependent on foreign assistance once the third-party actors depart. Since the logic of peacebuilding relies on building and strengthening institutions to alter societal beliefs and behaviour, success relies on the populations' endorsement of these institutions. Any third party attempt at institution building without genuine domestic support will result in hollow institutions - this can lead to a situation in which democratic institutions are established before domestic politics have developed in a liberal, democratic fashion, and an unstable polity.

Implementation

Barnett et al. criticizes peacebuilding organizations for undertaking supply-driven rather than demand-driven peacebuilding; they provide the peacebuilding services in which their organization specializes, not necessarily those that the recipient most needs.[46] In addition, he argues that many of their actions are based on organizations precedent rather than empirical analysis of which interventions are and are not effective.[9] More recently, Ben Hillman has criticized international donor efforts to strengthen local governments in the wake of conflict. He argues that international donors typically do not have the knowledge, skills or resources to bring meaningful change to the way post-conflict societies are governed.[47][48]

Perpetuation of cultural hegemony

Many academics argue that peacebuilding is a manifestation of liberal internationalismand therefore imposes Western values and practices onto other cultures. Mac Ginty states that although peacebuilding does not project all aspects of Western culture on to the recipient states, it does transmit some of them, including concepts likeneoliberalism that the West requires recipients of aid to follow more closely than most Western countries do.[49] Barnett also comments that the promotion of liberalization and democratization may undermine the peacebuilding process if security and stable institutions are not pursued concurrently.[50] Richmond has shown how 'liberal peacebuilding' represents a political encounter that may produce a post-liberal form of peace. Local and international actors, norms, institutions and interests engage with each other in various different contexts, according to their respective power relations and their different conceptions of legitimate authority structures.[51]

See also

- Conflict resolution

- Nation-building

- Peacemaking

- Peacekeeping

- State-building

- Environmental peacebuilding

- Religion and peacebuilding

- Peace and conflict studies

Notes

- Coning, C (2013). "Understanding Peacebuilding as Essentially Local". Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 2 (1): 6. doi:10.5334/sta.as.

- 454654, Jennifer M. (2007). "Can Peacekeepers Be Peacebuilders?". International Peacekeeping 14 (3): 323–338. doi:10.1080/13533310701422901.

- Peacebuilding & The United Nations, United Nations Peacebuilding Support Office, United Nations. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- Keating XXXIV

- "An Agenda for Peace". UN Secretary-General. 31 Jan 1992. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Barnett 36

- "About PSBO". United Nations. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- Barnett 43

- Barnett 53

- Sandole 92, 101

- Sandole 35

- Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). "Approaches- Peacebuilding". Conflict Management Toolkit. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- Keating XXXVII

- Sandole 13-14

- Sandole 12

- Barnett et al 49-50

- Mac Ginty 212

- Mac Ginty, R (2012). "Against Stabilization". Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 1 (1): 20–30. doi:10.5334/sta.ab.

- "Mandate of the Peacebuilding Commission". United Nations. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- "How we fund". United Nations. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- Barnett et al. 38

- Barnett et al. 43

- ADE, Thematic Evaluation of European Commission Support to Conflict Prevention and Peace-building, Evaluation for the Evaluation Unit of DEVCO, October 2011,http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/how/evaluation/evaluation_reports/2011/1291_docs_en.htm<>

- See the 2012 report of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) [1]

- Barnett et al. 38-40

- Edward Luttwak "Franco-German Reconciliation: The overlooked role of the Moral Re-Armament movement", in Douglas Johnston and Cynthia Sampson (eds.), Religion, the Missing Dimension of Statecraft, Oxford University Press, 1994, pp37-63.

- See the 2012 report of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA), page 20[2]

- Peacemaker Camp 2007, website

- [3].

- Porter 190

- "Policy Issues". United Nations. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Porter 184

- "Women's Participation in Peacebuilding" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. Retrieved2 April 2012.

- Porter 185

- "United Nations Peacebuilding Commission". United Nations. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- "Where we fund-United Nations Peacebuilding Fund". United Nations. Retrieved 10 April2012.

- Keating 120

- Mac Ginty 180

- Keating XLII-XLIII

- Tarnoff 14

- Tarnoff 2

- "2010 Review". United Nations. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Moore, Jina. "United Nations Peacebuilding Commission in Africa". 9 Dec 2011. Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- Steinert, Janina Isabel; Grimm, Sonja (2015-11-01). "Too good to be true? United Nations peacebuilding and the democratization of war-torn states". Conflict Management and Peace Science 32 (5): 513–535. doi:10.1177/0738894214559671. ISSN 0738-8942.

- David Chandler, Empire in Denial: The Politics of State-building, London: Pluto Press, 2006.

- Barnett 48

- Hillman, Ben (2011). "The Policymaking Dimension of Post-Conflict Governance: the Experience of Aceh, Indonesia". Conflict Security and Development 11 (5): 133–153.

- Hillman, Ben (2012). "Public Administration Reform in Post-Conflict Societies: Lessons from Aceh, Indonesia". Public Administration and Development 33: 1–14. doi:10.1002/pad.1643.

- Mac Ginty 38

- Barnett 51

- Oliver P Richmond, A Post-Liberal Peace, Routledge, 2011

References

- Barnett, Michael; Kim, Hunjoon; O'Donnell, Madalene; Sitea, Laura (2007). "Peacebuilding: What Is in a Name?". Global Governance 13: 35–58.

- Keating, Tom; Knight, W., eds. (2004). Building Sustainable Peace. Canada: United Nations University Press and The University of Alberta Press. ISBN 92-808-1101-0.

- Mac Ginty, Roger (2011). International Peacebuilding and Local Resistance. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-27376-4.

- Porter, Elisabeth (2007). Peacebuilding: Women in International Perspective. Oxon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-39791-9.

- Richmond, Oliver (2011). A Post-Liberal Peace. UK: Routledge.

- Sandole, Dennis (2010). Peacebuilding. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-4165-2.

- Schirch, Lisa (2006) Little Book of Strategic Peacebuilding. PA: Good Books.

- Schirch, Lisa (2013) Conflict Assessment & Peacebuilding Planning. CO: Lynn Reinner Press.

- Tarnoff, Curt; Marian L. Lawson (2011). Foreign Aid: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy (Technical report). Congressional Research Service. R40213.

External links

- Catholic Relief Services: Peacebuilding

- United Nations Peacebuilding Commission

- United Nations Rule of Law: Peacebuilding, on the relationship between peacebuilding, the rule of law and theUnited Nations.

- Building Cultures of Peace: Transdisciplinary Voices of Hope and Action, Elavie Ndura-Ouédraogo and Randall Amster (eds.), UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009.

- Peace, Peacebuilding, Peacemaking, in: Berghof Glossary on Conflict Transformation (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Berghof Foundation. 2012. pp. 59–64.ISBN 978-3-941514-09-6. Retrieved 6 March 2015.