Scholarly approaches to mysticism include typologies of mysticism and the explanation of mystical states. Since the 19th century, mystical experience has evolved as a distinctive concept. It is closely related to "mysticism" but lays sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior, whereas mysticism encompasses a broad range of practices aiming at a transformation of the person, not just inducing mystical experiences.

There is a longstanding discussion on the nature of so-called "introvertive mysticism." Perennialists regard this kind of mysticism to be universal. A popular variant of perennialism sees various mystical traditions as pointing to one universal transcendental reality, for which those experiences offer the proof. The perennial position is "largely dismissed by scholars" but "has lost none of its popularity". Instead, a constructionist approach became dominant during the 1970s, which states that mystical experiences are mediated by pre-existing frames of reference, while the attribution approach focuses on the (religious) meaning that is attributed to specific events.

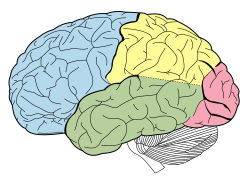

Some neurological research has attempted to identify which areas in the brain are involved in so-called "mystical experience" and the temporal lobe is often claimed to play a significant role,[3][4][5] likely attributable to claims made in Vilayanur Ramachandran's 1998 book, Phantoms in the Brain,[6] However, these claims have not stood up to scrutiny.[7]

In mystical and contemplative traditions, mystical experiences are not a goal in themselves, but part of a larger path of self-transformation.

Typologies of mysticism[edit]

Early studies[edit]

Lay scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries began their studies on the historical and psychological descriptive analysis of the mystical experience, by investigating examples and categorizing it into types. Early notable examples include William James in "The Varieties of Religious Experience" (1902); the study of the term "cosmic consciousness" by Edward Carpenter (1892)[8] and psychiatrist Richard Bucke (in his book Cosmic Consciousness, 1901); the definition of "oceanic feeling" by Romain Rolland (1927) and its study by Freud; Rudolf Otto's description of the "numinous" (1917) and its studies by Jung; Friedrich von Hügel in The Mystical Element of Religion (1908); Evelyn Underhill in her work Mysticism (1911); Aldous Huxley in The Perennial Philosophy (1945).

R. C. Zaehner – natural and religious mysticism[edit]

R. C. Zaehner distinguishes between three fundamental types of mysticism, namely theistic, monistic, and panenhenic ("all-in-one") or natural mysticism. The theistic category includes most forms of Jewish, Christian and Islamic mysticism and occasional Hindu examples such as Ramanuja and the Bhagavad Gita. The monistic type, which according to Zaehner is based upon the experience of the unity of one's soul in isolation from the material and psychic world,[note 1] includes early Buddhism and Hindu schools such as Samkhya and Advaita vedanta. Nature mysticism refers to "an experience of Nature in all things or of all things as being one," and includes, for instance, Zen Buddhism, Taoism, much Upanishadic thought, as well as American Transcendentalism. Within the second 'monistic' camp, Zaehner draws a clear distinction between the dualist 'isolationist' ideal of Samkhya, the historical Buddha, and various gnostic sects, and the non-dualist position of Advaita vedanta. According to the former, the union of an individual spiritual monad (soul) and body is "an unnatural state of affairs, and salvation consists in returning to one's own natural 'splendid isolation' in which one contemplates oneself forever in timeless bliss." The latter approach, by contrast, identifies the 'individual' soul with the All, thus emphasizing non-dualism: thou art that."

Zaehner considers theistic mysticism to be superior to the other two categories, because of its appreciation of God, but also because of its strong moral imperative. Zaehner is directly opposing the views of Aldous Huxley. Natural mystical experiences are in Zaehner's view of less value because they do not lead as directly to the virtues of charity and compassion. Zaehner is generally critical of what he sees as narcissistic tendencies in nature mysticism.[note 2]

Zaehner has been criticised by Paden for the "theological violence" which his approach does to non-theistic traditions, "forcing them into a framework which privileges Zaehner's own liberal Catholicism." That said, it is clear from many of Zaehner's other writings (e.g., Our Savage God, Zen, Drugs and Mysticism, At Sundry Times, Hinduism) that such a criticism is rather unfair.

Walter T. Stace – extrovertive and introvertive mysticism[edit]

Zaehner has also been criticised by Walter Terence Stace in his book Mysticism and philosophy (1960) on similar grounds. Stace argues that doctrinal differences between religious traditions are inappropriate criteria when making cross-cultural comparisons of mystical experiences. Stace argues that mysticism is part of the process of perception, not interpretation, that is to say that the unity of mystical experiences is perceived, and only afterwards interpreted according to the perceiver’s background. This may result in different accounts of the same phenomenon. While an atheist describes the unity as “freed from empirical filling”, a religious person might describe it as “God” or “the Divine”.[12] In “Mysticism and Philosophy”, one of Stace’s key questions is whether there are a set of common characteristics to all mystical experiences.[12]

Based on the study of religious texts, which he took as phenomenological descriptions of personal experiences, and excluding occult phenomena, visions, and voices, Stace distinguished two types of mystical experience, namely extrovertive and introvertive mysticism. He describes extrovertive mysticism as an experience of unity within the world, whereas introvertive mysticism is "an experience of unity devoid of perceptual objects; it is literally an experience of 'no-thing-ness'". The unity in extrovertive mysticism is with the totality of objects of perception. While perception stays continuous, “unity shines through the same world”; the unity in introvertive mysticism is with a pure consciousness, devoid of objects of perception, “pure unitary consciousness, wherein awareness of the world and of multiplicity is completely obliterated.”[16] According to Stace such experiences are nonsensical and nonintellectual, under a total “suppression of the whole empirical content.”[17]

Table 1: Common Characteristics of Extrovertive and Introvertive Mystical Experiences as in Stace (1960)| Common Characteristics of Extrovertive Mystical Experiences | Common Characteristics of Introvertive Mystical Experiences |

|---|

| 1. The Unifying Vision - all things are One | 1. The Unitary Consciousness; the One, the Void; pure consciousness |

| 2. The more concrete apprehension of the One as an inner subjectivity, or life, in all things | 2. Nonspatial, nontemporal |

| 3. Sense of objectivity or reality | 3. Sense of objectivity or reality |

| 4. Blessedness, peace, etc. | 4. Blessedness, peace, etc. |

| 5. Feeling of the holy, sacred, or divine | 5. Feeling of the holy, sacred, or divine |

| 6. Paradoxicality | 6. Paradoxicality |

| 7. Alleged by mystics to be ineffable | 7. Alleged by mystics to be ineffable |

Stace finally argues that there is a set of seven common characteristics for each type of mystical experience, with many of them overlapping between the two types. Stace furthermore argues that extrovertive mystical experiences are on a lower level than introvertive mystical experiences.

Stace's categories of "introvertive mysticism" and "extrovertive mysticism" are derived from Rudolf Otto's "mysticism of introspection" and "unifying vision".

William Wainwright distinguishes four different kinds of extrovert mystical experience, and two kinds of introvert mystical experience:[web 1]

- Extrovert: experiencing the unity of nature; experiencing nature as a living presence; experiencing all nature-phenomena as part of an eternal now; the "unconstructed experience" of Buddhism.

- Introvert: pure empty consciousness; the "mutual love" of theistic experiences.

Richard Jones, following William Wainwright, elaborated on the distinction, showing different types of experiences in each category:

- Extrovertive experiences: the sense of connectedness (“unity”) of oneself with nature, with a loss of a sense of boundaries within nature; the luminous glow to nature of “nature mysticism”; the presence of God immanent in nature outside of time shining through nature of “cosmic consciousness”; the lack of separate, self-existing entities of mindfulness states.

- Introvertive experiences: theistic experiences of connectedness or identity with God in mutual love; nonpersonal differentiated experiences; the depth-mystical experience empty of all differentiable content.

Following Stace's lead, Ralph Hood developed the "Mysticism scale." According to Hood, the introvertive mystical experience may be a common core to mysticism independent of both culture and person, forming the basis of a "perennial psychology". According to Hood, "the perennialist view has strong empirical support," since his scale yielded positive results across various cultures,[note 3] stating that mystical experience as operationalized from Stace's criteria is identical across various samples.[note 4]

Although Stace's work on mysticism received a positive response, it has also been strongly criticised in the 1970s and 1980s, for its lack of methodological rigueur and its perennialist pre-assumptions.[web 1] Major criticisms came from Steven T. Katz in his influential series of publications on mysticism and philosophy,[note 5] and from Wayne Proudfoot in his Religious experience (1985).

Masson and Masson criticised Stace for using a "buried premise," namely that mysticism can provide valid knowledge of the world, equal to science and logic. A similar criticism has been voiced by Jacob van Belzen toward Hood, noting that Hood validated the existence of a common core in mystical experiences, but based on a test which presupposes the existence of such a common core, noting that "the instrument used to verify Stace's conceptualization of Stace is not independent of Stace, but based on him." Belzen also notes that religion does not stand on its own, but is embedded in a cultural context, which should be taken into account. To this criticism Hood et al. answer that universalistic tendencies in religious research "are rooted first in inductive generalizations from cross-cultural consideration of either faith or mysticism," stating that Stace sought out texts which he recognized as an expression of mystical expression, from which he created his universal core. Hood therefore concludes that Belzen "is incorrect when he claims that items were presupposed."[note 6]

Mystical experience[edit]

The term "mystical experience" has become synonymous with the terms "religious experience", spiritual experience and sacred experience. A "religious experience" is a subjective experience which is interpreted within a religious framework. The concept originated in the 19th century, as a defense against the growing rationalism of western society. Wayne Proudfoot traces the roots of the notion of "religious experience" to the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that religion is based on a feeling of the infinite. The notion of "religious experience" was used by Schleiermacher to defend religion against the growing scientific and secular critique. It was adopted by many scholars of religion, of which William James was the most influential. A broad range of western and eastern movements have incorporated and influenced the emergence of the modern notion of "mystical experience", such as the Perennial philosophy, Transcendentalism, Universalism, the Theosophical Society, New Thought, Neo-Vedanta and Buddhist modernism.

William James[edit]

William James popularized the use of the term "religious experience" in his The Varieties of Religious Experience. James wrote:

In mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness. This is the everlasting and triumphant mystical tradition, hardly altered by differences of clime or creed. In Hinduism, in Neoplatonism, in Sufism, in Christian mysticism, in Whitmanism, we find the same recurring note, so that there is about mystical utterances an eternal unanimity which ought to make a critic stop and think, and which bring it about that the mystical classics have, as has been said, neither birthday nor native land.

This book is the classic study on religious or mystical experience, which influenced deeply both the academic and popular understanding of "religious experience".[web 1] James popularized the use of the term "religious experience"[note 7] in his Varieties,[web 1] and influenced the understanding of mysticism as a distinctive experience which supplies knowledge of the transcendental:[web 1]

Under the influence of William James' The Varieties of Religious Experience, heavily centered on people's conversion experiences, most philosophers' interest in mysticism has been in distinctive, allegedly knowledge-granting "mystical experiences.""[web 1]

James emphasized the personal experience of individuals, and describes a broad variety of such experiences in The Varieties of Religious Experience. He considered the "personal religion" to be "more fundamental than either theology or ecclesiasticism",[note 8] and defines religion as

...the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine.

According to James, mystical experiences have four defining qualities:

- Ineffability. According to James the mystical experience "defies expression, that no adequate report of its content can be given in words".

- Noetic quality. Mystics stress that their experiences give them "insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect." James referred to this as the "noetic" (or intellectual) "quality" of the mystical.

- Transiency. James notes that most mystical experiences have a short occurrence, but their effect persists.

- Passivity. According to James, mystics come to their peak experience not as active seekers, but as passive recipients.

James recognised the broad variety of mystical schools and conflicting doctrines both within and between religions. Nevertheless,

...he shared with thinkers of his era the conviction that beneath the variety could be carved out a certain mystical unanimity, that mystics shared certain common perceptions of the divine, however different their religion or historical epoch,

According to Jesuit scholar William Harmless, "for James there was nothing inherently theological in or about mystical experience", and felt it legitimate to separate the mystic's experience from theological claims. Harmless notes that James "denies the most central fact of religion", namely that religion is practiced by people in groups, and often in public. He also ignores ritual, the historicity of religious traditions, and theology, instead emphasizing "feeling" as central to religion.

Inducement of mystical experience[edit]

Dan Merkur makes a distinction between trance states and reverie states.[web 2] According to Merkur, in trance states the normal functions of consciousness are temporarily inhibited, and trance experiences are not filtered by ordinary judgements, and seem to be real and true.[web 2] In reverie states, numinous experiences are also not inhibited by the normal functions of consciousness, but visions and insights are still perceived as being in need of interpretation, while trance states may lead to a denial of physical reality.[web 2]

Most mystical traditions warn against an attachment to mystical experiences, and offer a "protective and hermeneutic framework" to accommodate these experiences. These same traditions offer the means to induce mystical experiences, which may have several origins:

- Spontaneous; either apparently without any cause, or by persistent existential concerns, or by neurophysiological origins;

- Religious practices, such as contemplation, meditation, and mantra-repetition;

- Entheogens (drugs)

- Neurophysiological origins, such as temporal lobe epilepsy.

Influence[edit]

The concept of "mystical experience" has influenced the understanding of mysticism as a distinctive experience which supplies knowledge of a transcendental reality, cosmic unity, or ultimate truths.[web 1][note 9] Scholars, like Stace and Forman, have tended to exclude visions, near death experiences and parapsychological phenomena from such "special mental states," and focus on sudden experiences of oneness, though neurologically they all seem to be related.

Criticism of the concept of "mystical experience"[edit]

The notion of "experience", however, has been criticized in religious studies today. Robert Sharf points out that "experience" is a typical Western term, which has found its way into Asian religiosity via western influences.[note 10] The notion of "experience" introduces a false notion of duality between "experiencer" and "experienced", whereas the essence of kensho is the realisation of the "non-duality" of observer and observed. "Pure experience" does not exist; all experience is mediated by intellectual and cognitive activity. The specific teachings and practices of a specific tradition may even determine what "experience" someone has, which means that this "experience" is not the proof of the teaching, but a result of the teaching. A pure consciousness without concepts, reached by "cleaning the doors of perception",[note 11] would be an overwhelming chaos of sensory input without coherence.

Constructivists such as Steven Katz reject any typology of experiences since each mystical experience is deemed unique.

Other critics point out that the stress on "experience" is accompanied with favoring the atomic individual, instead of the shared life of the community. It also fails to distinguish between episodic experience, and mysticism as a process, that is embedded in a total religious matrix of liturgy, scripture, worship, virtues, theology, rituals and practices.

Richard King also points to disjunction between "mystical experience" and social justice:

The privatisation of mysticism – that is, the increasing tendency to locate the mystical in the psychological realm of personal experiences – serves to exclude it from political issues as social justice. Mysticism thus becomes seen as a personal matter of cultivating inner states of tranquility and equanimity, which, rather than seeking to transform the world, serve to accommodate the individual to the status quo through the alleviation of anxiety and stress.

Perennialism, constructionism and contextualism[edit]

Scholarly research on mystical experiences in the 19th and 20th century was dominated by a discourse on "mystical experience," laying sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior. Perennialists regard those various experiences traditions as pointing to one universal transcendental reality, for which those experiences offer the prove. In this approach, mystical experiences are privatised, separated from the context in which they emerge. William James, in his The Varieties of Religious Experience, was highly influential in further popularising this perennial approach and the notion of personal experience as a validation of religious truths.

The essentialist model argues that mystical experience is independent of the sociocultural, historical and religious context in which it occurs, and regards all mystical experience in its essence to be the same. According to this "common core-thesis", different descriptions can mask quite similar if not identical experiences:

[P]eople can differentiate experience from interpretation, such that different interpretations may be applied to otherwise identical experiences".

Principal exponents of the perennialist position were William James, Walter Terence Stace, who distinguishes extroverted and introverted mysticism, in response to R. C. Zaehner's distinction between theistic and monistic mysticism; Huston Smith; and Ralph W. Hood, who conducted empirical research using the "Mysticism Scale", which is based on Stace's model.[note 12]

Since the 1960s, social constructionism argued that mystical experiences are "a family of similar experiences that includes many different kinds, as represented by the many kinds of religious and secular mystical reports". The constructionist states that mystical experiences are fully constructed by the ideas, symbols and practices that mystics are familiar with, shaped by the concepts "which the mystic brings to, and which shape, his experience". What is being experienced is being determined by the expectations and the conceptual background of the mystic. Critics of the "common-core thesis" argue that

[N]o unmediated experience is possible, and that in the extreme, language is not simply used to interpret experience but in fact constitutes experience.

The principal exponent of the constructionist position is Steven T. Katz, who, in a series of publications,[note 13] has made a highly influential and compelling case for the constructionist approach.

The perennial position is "largely dismissed by scholars", but "has lost none of its popularity". The contextual approach has become the common approach, and takes into account the historical and cultural context of mystical experiences.

Steven Katz – constructionism[edit]

After Walter Stace's seminal book in 1960, the general philosophy of mysticism received little attention.[note 14] But in the 1970s the issue of a universal "perennialism" versus each mystical experience being was reignited by Steven Katz. In an often-cited quote he states:

There are NO pure (i.e. unmediated) experiences. Neither mystical experience nor more ordinary forms of experience give any indication, or any ground for believing, that they are unmediated [...] The notion of unmediated experience seems, if not self-contradictory, at best empty. This epistemological fact seems to me to be true, because of the sort of beings we are, even with regard to the experiences of those ultimate objects of concern with which mystics have had intercourse, e.g., God, Being, Nirvana, etc.[note 15]

According to Katz (1978), Stace typology is "too reductive and inflexible," reducing the complexities and varieties of mystical experience into "improper categories." According to Katz, Stace does not notice the difference between experience and interpretation, but fails to notice the epistemological issues involved in recognizing such experiences as "mystical," and the even more fundamental issue of which conceptual framework precedes and shapes these experiences. Katz further notes that Stace supposes that similarities in descriptive language also implies a similarity in experience, an assumption which Katz rejects. According to Katz, close examination of the descriptions and their contexts reveals that those experiences are not identical. Katz further notes that Stace held one specific mystical tradition to be superior and normative, whereas Katz rejects reductionist notions and leaves God as God, and Nirvana as Nirvana.

According to Paden, Katz rejects the discrimination between experiences and their interpretations. Katz argues that it is not the description, but the experience itself which is conditioned by the cultural and religious background of the mystic. According to Katz, it is not possible to have pure or unmediated experience.

Yet, according to Laibelman, Katz did not say that the experience can't be unmediated; he said that the conceptual understanding of the experience can't be unmediated, and is based on culturally mediated preconceptions. According to Laibelman, misunderstanding Katz's argument has led some to defend the authenticity of "pure consciousness events," while this is not the issue. Laibelman further notes that a mystic's interpretation is not necessarily more true or correct than the interpretation of an uninvolved observer.

Robert Forman – pure consciousness event[edit]

Robert Forman has criticised Katz' approach, arguing that lay-people who describe mystical experiences often notice that this experience involves a totally new form of awareness, which can't be described in their existing frame of reference. Newberg argued that there is neurological evidence for the existence of a "pure consciousness event" empty of any constructionist structuring.

Richard Jones – constructivism, anticonstructivism, and perennialism[edit]

Richard H. Jones believes that the dispute between "constructionism" and "perennialism" is ill-formed. He draws a distinction between "anticonstructivism" and "perennialism": constructivism can rejected with respect to a certain class of mystical experiences without ascribing to a perennialist philosophy on the relation of mystical doctrines. Constructivism versus anticonstructivism is a matter of the nature of mystical experiences themselves while perennialism is a matter of mystical traditions and the doctrines they espouse. One can reject constructivism about the nature of mystical experiences without claiming that all mystical experiences reveal a cross-cultural "perennial truth". Anticonstructivists can advocate contextualism as much as constructivists do, while perennialists reject the need to study mystical experiences in the context of a mystic's culture since all mystics state the same universal truth.

Contextualism and attribution theory[edit]

The theoretical study of mystical experience has shifted from an experiential, privatised and perennialist approach to a contextual and empirical approach. The contextual approach, which also includes constructionism and attribution theory, takes into account the historical and cultural context.[web 1] Neurological research takes an empirical approach, relating mystical experiences to neurological processes.

Wayne Proudfoot proposes an approach that also negates any alleged cognitive content of mystical experiences: mystics unconsciously merely attribute a doctrinal content to ordinary experiences. That is, mystics project cognitive content onto otherwise ordinary experiences having a strong emotional impact. Objections have been raised concerning Proudfoot’s use of the psychological data. This approach, however, has been further elaborated by Ann Taves. She incorporates both neurological and cultural approaches in the study of mystical experience.

Many religious and mystical traditions see religious experiences (particularly that knowledge that comes with them) as revelations caused by divine agency rather than ordinary natural processes. They are considered real encounters with God or gods, or real contact with higher-order realities of which humans are not ordinarily aware.[web 4]

Neurological research[edit]

| Lobes of the human brain |

|---|

|

| Lobes of the human brain (temporal lobe is shown in green) |

The scientific study of mysticism today focuses on two topics: identifying the neurological bases and triggers of mystical experiences, and demonstrating the purported benefits of meditation. Correlates between mystical experiences and neurological activity have been established, pointing to the temporal lobe as the main locus for these experiences, while Andrew B. Newberg and Eugene G. d'Aquili have also pointed to the parietal lobe. Recent research points to the relevance of the default mode network.[93]

Temporal lobe[edit]

The temporal lobe generates the feeling of "I", and gives a feeling of familiarity or strangeness to the perceptions of the senses.[web 5] It seems to be involved in mystical experiences,[web 5] and in the change in personality that may result from such experiences.[web 5] There is a long-standing notion that epilepsy and religion are linked, and some religious figures may have had temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). Raymond Bucke's Cosmic Consciousness (1901) contains several case-studies of persons who have realized "cosmic consciousness";[web 5] several of these cases are also being mentioned in J.E. Bryant's 1953 book, Genius and Epilepsy, which has a list of more than 20 people that combines the great and the mystical. James Leuba's The psychology of religious mysticism noted that "among the dread diseases that afflict humanity there is only one that interests us quite particularly; that disease is epilepsy."

Slater and Beard renewed the interest in TLE and religious experience in the 1960s.[7] Dewhurst and Beard (1970) described six cases of TLE-patients who underwent sudden religious conversions. They placed these cases in the context of several western saints with a sudden conversion, who were or may have been epileptic. Dewhurst and Beard described several aspects of conversion experiences, and did not favor one specific mechanism.

Norman Geschwind described behavioral changes related to temporal lobe epilepsy in the 1970s and 1980s. Geschwind described cases which included extreme religiosity, now called Geschwind syndrome, and aspects of the syndrome have been identified in some religious figures, in particular extreme religiosity and hypergraphia (excessive writing). Geschwind introduced this "interictal personality disorder" to neurology, describing a cluster of specific personality characteristics which he found characteristic of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Critics note that these characteristics can be the result of any illness, and are not sufficiently descriptive for patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.[web 6]

Neuropsychiatrist Peter Fenwick, in the 1980s and 1990s, also found a relationship between the right temporal lobe and mystical experience, but also found that pathology or brain damage is only one of many possible causal mechanisms for these experiences. He questioned the earlier accounts of religious figures with temporal lobe epilepsy, noticing that "very few true examples of the ecstatic aura and the temporal lobe seizure had been reported in the world scientific literature prior to 1980". According to Fenwick, "It is likely that the earlier accounts of temporal lobe epilepsy and temporal lobe pathology and the relation to mystic and religious states owes more to the enthusiasm of their authors than to a true scientific understanding of the nature of temporal lobe functioning."[web 7]

The occurrence of intense religious feelings in epileptic patients in general is rare,[web 5] with an incident rate of ca. 2-3%. Sudden religious conversion, together with visions, has been documented in only a small number of individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy. The occurrence of religious experiences in TLE-patients may as well be explained by religious attribution, due to the background of these patients.[7] Nevertheless, the Neuroscience of religion is a growing field of research, searching for specific neurological explanations of mystical experiences. Those rare epileptic patients with ecstatic seizures may provide clues for the neurological mechanisms involved in mystical experiences, such as the anterior insular cortex, which is involved in self-awareness and subjective certainty.

Anterior insula[edit]

The insula of the right side, exposed by

removing the opercula. A common quality in mystical experiences is ineffability, a strong feeling of certainty which cannot be expressed in words. This ineffability has been threatened with scepticism. According to Arthur Schopenhauer the inner experience of mysticism is philosophically unconvincing.[note 16] In The Emotion Machine, Marvin Minsky argues that mystical experiences only seem profound and persuasive because the mind's critical faculties are relatively inactive during them.[note 18]

Geschwind and Picard propose a neurological explanation for this subjective certainty, based on clinical research of epilepsy.[note 19] According to Picard, this feeling of certainty may be caused by a dysfunction of the anterior insula, a part of the brain which is involved in interoception, self-reflection, and in avoiding uncertainty about the internal representations of the world by "anticipation of resolution of uncertainty or risk". This avoidance of uncertainty functions through the comparison between predicted states and actual states, that is, "signaling that we do not understand, i.e., that there is ambiguity." Picard notes that "the concept of insight is very close to that of certainty," and refers to Archimedes "Eureka!"[note 20] Picard hypothesizes that in ecstatic seizures the comparison between predicted states and actual states no longer functions, and that mismatches between predicted state and actual state are no longer processed, blocking "negative emotions and negative arousal arising from predictive unceertainty," which will be experienced as emotional confidence. Picard concludes that "[t]his could lead to a spiritual interpretation in some individuals."

Parietal lobe[edit]

Andrew B. Newberg and Eugene G. d'Aquili, in their book Why God Won't Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief, take a perennial stance, describing their insights into the relationship between religious experience and brain function. d'Aquili describes his own meditative experiences as "allowing a deeper, simpler part of him to emerge", which he believes to be "the truest part of who he is, the part that never changes." Not content with personal and subjective descriptions like these, Newberg and d'Aquili have studied the brain-correlates to such experiences. They scanned the brain blood flow patterns during such moments of mystical transcendence, using SPECT-scans, to detect which brain areas show heightened activity. Their scans showed unusual activity in the top rear section of the brain, the "posterior superior parietal lobe", or the "orientation association area (OAA)" in their own words. This area creates a consistent cognition of the physical limits of the self. This OAA shows a sharply reduced activity during meditative states, reflecting a block in the incoming flow of sensory information, resulting in a perceived lack of physical boundaries. According to Newberg and d'Aquili,

This is exactly how Robert[who?] and generations of Eastern mystics before him have described their peak meditative, spiritual and mystical moments.

Newberg and d'Aquili conclude that mystical experience correlates to observable neurological events, which are not outside the range of normal brain function. They also believe that

...our research has left us no choice but to conclude that the mystics may be on to something, that the mind’s machinery of transcendence may in fact be a window through which we can glimpse the ultimate realness of something that is truly divine.[note 21]

Why God Won't Go Away "received very little attention from professional scholars of religion".[note 22][note 23] According to Bulkeley, "Newberg and D'Aquili seem blissfully unaware of the past half century of critical scholarship questioning universalistic claims about human nature and experience".[note 24] Matthew Day also notes that the discovery of a neurological substrate of a "religious experience" is an isolated finding which "doesn't even come close to a robust theory of religion".

Default mode network[edit]

Recent studies evidenced the relevance of the default mode network in spiritual and self-transcending experiences. Its functions are related, among others, to self-reference and self-awareness, and new imaging experiments during meditation and the use of hallucinogens indicate a decrease in the activity of this network mediated by them, leading some studies to base on it a probable neurocognitive mechanism of the dissolution of the self, which occurs in some mystical phenomena.[93][120][121]

Spiritual development and self-transformation[edit]

In mystical and contemplative traditions, mystical experiences are not a goal in themselves, but part of a larger path of self-transformation. For example, the Zen Buddhist training does not end with kenshō, but practice is to be continued to deepen the insight and to express it in daily life.[note 25] To deepen the initial insight of kensho, shikantaza and kōan-study are necessary. This trajectory of initial insight followed by a gradual deepening and ripening is expressed by Linji Yixuan in his Three mysterious Gates, the Five Ranks, the Four Ways of Knowing of Hakuin, and the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures which detail the steps on the Path.

See also[edit]

- ^ Compare the work of C.G. Jung.

- ^ See especially Zaehner, R. C., Mysticism Sacred and Profane, Oxford University Press, Chapters 3,4, and 6.

- ^ Hood: "...it seems fair to conclude that the perennialist view has strong empirical support, insofar as regardless of the language used in the M Scale, the basic structure of the experience remains constant across diverse samples and cultures. This is a way of stating the perennialist thesis in measurable terms.

- ^ Hood: "[E]mpirically, there is strong support to claim that as operationalized from Stace's criteria, mystical experience is identical as measured across diverse samples, whether expressed in "neutral language" or with either "God" or "Christ" references.

- ^ * Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis (Oxford University Press, 1978)

* Mysticism and Religious Traditions (Oxford University Press, 1983)

* Mysticism and Language (Oxford University Press, 1992)

* Mysticism and Sacred Scripture (Oxford University Press, 2000) - ^ Robert Sharf has criticised the idea that religious texts describe individual religious experience. According to Sharf, their authors go to great lengths to avoid personal experience, which would be seen as invalidating the presumed authority of the historical tradition.

- ^ The term "mystical experience" has become synonymous with the terms "religious experience", spiritual experience and sacred experience.

- ^ James: "Churches, when once established, live at secondhand upon tradition; but the founders of every church owed their power originally to the fact of their direct personal communion with the divine. not only the superhuman founders, the Christ, the Buddha, Mahomet, but all the originators of Christian sects have been in this case; – so personal religion should still seem the primordial thing, even to those who continue to esteem it incomplete."

- ^ McClenon: "The doctrine that special mental states or events allow an understanding of ultimate truths. Although it is difficult to differentiate which forms of experience allow such understandings, mental episodes supporting belief in "other kinds of reality" are often labeled mystical [...] Mysticism tends to refer to experiences supporting belief in a cosmic unity rather than the advocation of a particular religious ideology."[web 3]

- ^ Roberarf: "[T]he role of experience in the history of Buddhism has been greatly exaggerated in contemporary scholarship. Both historical and ethnographic evidence suggests that the privileging of experience may well be traced to certain twentieth-century reform movements, notably those that urge a return to zazen or vipassana meditation, and these reforms were profoundly influenced by religious developments in the west ii[...] While some adepts may indeed experience "altered states" in the course of their training, critical analysis shows that such states do not constitute the reference point for the elaborate Buddhist discourse pertaining to the "path".

- ^ William Blake: "If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thru' narrow chinks of his cavern."[54]

- ^ Others include Frithjof Schuon, Rudolf Otto and Aldous Huxley.

- ^

- Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis (Oxford University Press, 1978)

- Mysticism and Religious Traditions (Oxford University Press, 1983)

- Mysticism and Language (Oxford University Press, 1992)

- Mysticism and Sacred Scripture (Oxford University Press, 2000)

- ^ Two notable exceptions are collections of essays by Wainwright 1981 and Jones 1983.

- ^ Original in Katz (1978), Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis, Oxford University Press

- ^ Schopenhauer: "In the widest sense, mysticism is every guidance to the immediate awareness of what is not reached by either perception or conception, or generally by any knowledge. The mystic is opposed to the philosopher by the fact that he begins from within, whereas the philosopher begins from without. The mystic starts from his inner, positive, individual experience, in which he finds himself as the eternal and only being, and so on. But nothing of this is communicable except the assertions that we have to accept on his word; consequently he is unable to convince.

- ^ Minsky's idea of 'some early Imprimer hiding in the mind' was an echo of Freud's belief that mystical experience was essentially infantile and regressive, i.e., a memory of 'Oneness' with the mother.

- ^ Meditator: It suddenly seemed as if I was surrounded by an immensely powerful Presence. I felt that a Truth had been "revealed" to me that was far more important than anything else, and for which I needed no further evidence. But when later I tried to describe this to my friends, I found that I had nothing to say except how wonderful that experience was. This peculiar type of mental state is sometimes called a "Mystical Experience" or "Rapture," "Ecstasy," or "Bliss." Some who undergo it call it "wonderful," but a better word might be "wonderless," because I suspect that such a state of mind may result from turning so many Critics off that one cannot find any flaws in it. What might that "powerful Presence" represent? It is sometimes seen as a deity, but I suspect that it is likely to be a version of some early Imprimer that for years has been hiding inside your mind.[note 17] In any case, such experiences can be dangerous—for some victims find them so compelling that they devote the rest of their lives to trying to get themselves back to that state again.

- ^ See also Francesca Sacco (2013-09-19), Can Epilepsy Unlock The Secret To Happiness?, Le Temps

- ^ See also satori in Japanese Zen

- ^ See Radhakrishnan for a similar stance on the value of religious experience. Radhakrishnan saw Hinduism as a scientific religion based on facts, apprehended via intuition or religious experience.[web 8] According to Radhakrishnan, "[i]f philosophy of religion is to become scientific, it must become empirical and found itself on religious experience".[web 8] He saw this empiricism exemplified in the Vedas: "The truths of the ṛṣis are not evolved as the result of logical reasoning or systematic philosophy but are the products of spiritual intuition, dṛṣti or vision. The ṛṣis are not so much the authors of the truths recorded in the Vedas as the seers who were able to discern the eternal truths by raising their life-spirit to the plane of universal spirit. They are the pioneer researchers in the realm of the spirit who saw more in the world than their followers. Their utterances are not based on transitory vision but on a continuous experience of resident life and power. When the Vedas are regarded as the highest authority, all that is meant is that the most exacting of all authorities is the authority of facts."[web 8] This stance is echoed by Ken Wilber: "The point is that we might have an excellent population of extremely evolved and developed personalities in the form of the world's great mystic-sages (a point which is supported by Maslow's studies). Let us, then, simply assume that the authentic mystic-sage represents the very highest stages of human development—as far beyond normal and average humanity as humanity itself is beyond apes. This, in effect, would give us a sample which approximates "the highest state of consciousness"—a type of "superconscious state." Furthermore, most of the mystic-sages have left rather detailed records of the stages and steps of their own transformations into the superconscious realms. That is, they tell us not only of the highest level of consciousness and superconsciousness, but also of all the intermediate levels leading up to it. If we take all these higher stages and add them to the lower and middle stages/levels which have been so carefully described and studied by Western psychology, we would then arrive at a fairly well-balanced and comprehensive model of the spectrum of consciousness."

- ^ See Michael Shermer (2001), Is God All in the Mind? for a review in Science.

- ^ According to Matthew Day, the book "is fatally compromised by conceptual confusions, obsolete scholarship, clumsy sleights of hand and untethered speculation". According to Matthew Day, Newberg and d'Aquili "consistently discount the messy reality of empirical religious heterogenity".

- ^ Bulkely (2003). "The Gospel According to Darwin: the relevance of cognitive neuroscience to religious studies". Religious Studies Review. 29 (2): 123–129.. Cited in

- ^ See, for example:

* Contemporary Chan Master Sheng Yen: "Ch'an expressions refer to enlightenment as "seeing your self-nature". But even this is not enough. After seeing your self-nature, you need to deepen your experience even further and bring it into maturation. You should have enlightenment experience again and again and support them with continuous practice. Even though Ch'an says that at the time of enlightenment, your outlook is the same as of the Buddha, you are not yet a full Buddha."

* Contemporary western Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennett: "One can easily get the impression that realization, kenshō, an experience of enlightenment, or however you wish to phrase it, is the end of Zen training. It is not. It is, rather, a new beginning, an entrance into a more mature phase of Buddhist training. To take it as an ending, and to "dine out" on such an experience without doing the training that will deepen and extend it, is one of the greatest tragedies of which I know. There must be continuous development, otherwise you will be as a wooden statue sitting upon a plinth to be dusted, and the life of Buddha will not increase."

References[edit]

- ^ Matthew Alper. The "God" Part of the Brain: A Scientific Interpretation of Human Spirituality and God.

- ^ James H. Austin. Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness. Archived from the original on 22 February 2004.

- ^ James H. Austin. Zen-Brain Reflections: Reviewing Recent Developments in Meditation and States of Consciousness. Archived from the original on 23 June 2006.

- ^ Ramachandran, V. & Blakeslee (1998). Phantoms in the Brain.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Aaen-Stockdale, Craig (2012). "Neuroscience for the Soul". The Psychologist. 25 (7): 520–523.

- ^ Harris, Kirsten. "The Evolution of Consciousness: Edward Carpenter's 'Towards Democracy'". Victorian Spiritualities (Leeds Working Papers in Victorian Studies).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Stace, Walter (1960). Mysticism and Philosophy. MacMillan. pp. 44–80.

- ^ Stace, Walter (1960). The Teachings of the Mystics. New York: The New American Library. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-451-60306-0.

- ^ Stace, Walter (1960). The Teachings of the Mystics. New York: The New American Library. pp. 15–18. ISBN 0-451-60306-0.

- ^ Quote DB

- ^ Jump up to:a b van Elk, Michiel; Aleman, André (February 2017). "Brain mechanisms in religion and spirituality: An integrative predictive processing framework". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 73: 359–378. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.031. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 28041787. S2CID 3984198.

- ^ Nutt, David; Chialvo, Dante R.; Tagliazucchi, Enzo; Feilding, Amanda; Shanahan, Murray; Hellyer, Peter John; Leech, Robert; Carhart-Harris, Robin Lester (2014). "The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 20. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020. ISSN 1662-5161. PMC 3909994. PMID 24550805.

- ^ Barrett, Frederick S.; Griffiths, Roland R. (2018). "Classic Hallucinogens and Mystical Experiences: Phenomenology and Neural Correlates". Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 36: 393–430. doi:10.1007/7854_2017_474. ISBN 978-3-662-55878-2. ISSN 1866-3370. PMC 6707356. PMID 28401522.

Sources[edit]

Published sources[edit]

- Barnard, William G. (1992), Explaining the Unexplainable: Wayne Proudfoot's Religious Experience, Journal of the American Academy of Religion 60 (no. 2): 231-57

- Barnard, William G. and Jeffrey J. Kripal, eds. (2002), Crossing Boundaries: Essays on the Ethical Status of Mysticism, Seven Bridges Press

- Beauregard, Mario and Denyse O'Leary (2007), The Spiritual Brain, Seven Bridges Press

- Bhattacharya, Vidhushekhara (1943), Gauḍapādakārikā, New York: HarperCollins

- Belzen, Jacob A.; Geels, Antoon (2003), Mysticism: A Variety of Psychological Perspectives, Rodopi

- Belzen, Jacob van (2010), Towards Cultural Psychology of Religion: Principles, Approaches, Applications, Springer Science & Business Media

- Bloom, Harold (2010), Aldous Huxley, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 9781438134376

- Bond, George D. (1992), The Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Bryant, Ernest J. (1953), Genius and Epilepsy. Brief sketches of Great Men Who Had Both, Concord, Massachusetts: Ye Old Depot Press

- Bryant, Edwin (2009), The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali: A New Edition, Translation, and Commentary, New York, USA: North Point Press, ISBN 978-0865477360

- Carrithers, Michael (1983), The Forest Monks of Sri Lanka

- Chapple, Christopher (1984), Introduction to "The Concise Yoga Vasistha", State University of New York

- Cobb, W.F. (2009), Mysticism and the Creed, BiblioBazaar, ISBN 978-1-113-20937-5

- Comans, Michael (2000), The Method of Early Advaita Vedānta: A Study of Gauḍapāda, Śaṅkara, Sureśvara, and Padmapāda, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Danto, Arthur C. (1987), Mysticism and Morality, New York: Columbia University Press

- Dasgupta, Surendranath (1975), A History of Indian Philosophy, 1, Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0412-0

- Day, Matthew (2009), Exotic experience and ordinary life. In: Micael Stausberg (ed.)(2009), "Contemporary Theories of Religion", pp. 115–129, Routledge, ISBN 9780203875926

- Devinsky, O. (2003), "Religious experiences and epilepsy", Epilepsy & Behavior, 4 (1): 76–77, doi:10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00680-7, PMID 12609231, S2CID 32445013

- Dewhurst, K.; Beard, A. (2003). "Sudden religious conversions in temporal lobe epilepsy. 1970" (PDF). Epilepsy & Behavior. 4 (1): 78–87. doi:10.1016/S1525-5050(02)00688-1. PMID 12609232. S2CID 28084208. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2007.

- Drvinsky, Julie; Schachter, Steven (2009), "Norman Geschwind's contribution to the understanding of behavioral changes in temporal lobe epilepsy: The February 1974 lecture", Epilepsy & Behavior, 15 (4): 417–424, doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.06.006, PMID 19640791, S2CID 22179745

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 1: India and China, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-89-1

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-90-7

- Evans, Donald. (1989), Can Philosophers Limit What Mystics Can Do?, Religious Studies, volume 25, pp. 53-60

- Forman, Robert K., ed. (1997), The Problem of Pure Consciousness: Mysticism and Philosophy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195355116

- Forman, Robert K. (1999), Mysticism, Albany: State University of New York Press

- Freud, Sigmund (1930), Civilization and Its Discontents

- Gschwind, Markus; Picard, Fabienne (2014), "Ecstatic Epileptic Seizures – the Role of the Insula in Altered Self-Awareness" (PDF), Epileptologie, 31: 87–98

- Gschwind, Markus; Picard, Fabienne (2016), "Ecstatic Epileptic Seizures: A Glimpse into the Multiple Roles of the Insula", Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 10: 21, doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00021, PMC 4756129, PMID 26924970

- Godman, David (1985), Be As You Are (PDF), Penguin, ISBN 0-14-019062-7, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2013

- Gombrich, Richard F. (1997), How Buddhism Began. The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2010), Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, Translated by Norman Waddell, Shambhala Publications

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (1996), New Age Religion and Western Culture. Esotericism in the mirror of Secular Thought, Leiden/New York/Koln: E.J. Brill

- Harmless, William (2007), Mystics, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780198041108

- Harper, Katherine Anne and Robert L. Brown (eds.) (2002), The Roots of Tantra, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-5306-5

- Hisamatsu, Shinʼichi (2002), Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition: Hisamatsu's Talks on Linji, University of Hawaii Press

- Holmes, Ernest (2010), The Science of Mind: Complete and Unabridged, Wilder Publications, ISBN 978-1604599893

- Horne, James R. (1996), mysticism and Vocation, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, ISBN 9780889202641

- Hood, Ralph W. (2003), "Mysticism", The Psychology of Religion. An Empirical Approach, New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 290–340

- Hood, Ralph W.; Streib, Heinz; Keller, Barbara; Klein, Constantin (2015), "The Contribution of the Study of "Spirituality" to the Psychology of Religion: Conclusions and Future Prospects", in Sreib, Heinz; Hood, Ralph W. (eds.), Semantics and Psychology of Spirituality: A Cross-Cultural Analysis, Springer

- Hori, Victor Sogen (1994), Teaching and Learning in the Zen Rinzai Monastery. In: Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol.20, No. 1, (Winter, 1994), 5–35 (PDF)

- Hori, Victor Sogen (1999), Translating the Zen Phrase Book. In: Nanzan Bulletin 23 (1999) (PDF)

- Hori, Victor Sogen (2006), The Steps of Koan Practice. In: John Daido Loori, Thomas Yuho Kirchner (eds), Sitting With Koans: Essential Writings on Zen Koan Introspection, Wisdom Publications

- Hügel, Friedrich, Freiherr von (1908), The Mystical Element of Religion: As Studied in Saint Catherine of Genoa and Her Friends, London: J.M. Dent

- Jacobs, Alan (2004), Advaita and Western Neo-Advaita. In: The Mountain Path Journal, autumn 2004, pages 81–88, Ramanasramam, archived from the original on 18 May 2015

- James, William (1982) [1902], The Varieties of Religious Experience, Penguin classics

- Jiyu-Kennett, Houn (2005), Roar of the Tigress, volume I. An Introduction to Zen: Religious Practice for Everyday Life (PDF), MOUNT SHASTA, CALIFORNIA: SHASTA ABBEY PRESS

- Jiyu-Kennett, Houn (2005), Roar of the Tigress, volume II. Zen for Spiritual Adults: Lectures Inspired by the Shōbōgenzō of Eihei Dōgen (PDF), MOUNT SHASTA, CALIFORNIA: SHASTA ABBEY PRESS

- Jones, Richard H. (1983), Mysticism Examined, Albany: State University of New York Press

- Jones, Richard H. (2004), Mysticism and Morality, Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books

- Jones, Richard H. (2016), Philosophy of Mysticism: Raids on the Ineffable, Albany: State University of New York Press

- Kapleau, Philip (1989), The Three Pillars of Zen, ISBN 978-0-385-26093-0

- Katz, Steven T. (1978), "Language, Epistemology, and Mysticism", in Katz, Steven T. (ed.), Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis, Oxford university Press

- Katz, Steven T. (2000), Mysticism and Sacred Scripture, Oxford University Press

- Kim, Hee-Jin (2007), Dōgen on Meditation and Thinking: A Reflection on His View of Zen, SUNY Press

- King, Richard (1999), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- King, Richard (2002), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- King, Sallie B. (1988), Two Epistemological Models for the Interpretation of Mysticism, Journal for the American Academy for Religion, volume 26, pp. 257-279

- Klein, Anne Carolyn; Tenzin Wangyal (2006), Unbounded Wholeness : Dzogchen, Bon, and the Logic of the Nonconceptual: Dzogchen, Bon, and the Logic of the Nonconceptual, Oxford University Press

- Klein, Anne Carolyn (2011), Dzogchen. In: Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass (eds.)(2011), The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy, Oxford University Press

- Kraft, Kenneth (1997), Eloquent Zen: Daitō and Early Japanese Zen, University of Hawaii Press

- Laibelman, Alan M. (2007), Discreteness, Continuity, & Consciousness: An Epistemological Unified Field Theory, Peter Lang

- Leuba, J.H. (1925), The psychology of religious mysticism, Harcourt, Brace

- Lewis, James R.; Melton, J. Gordon (1992), Perspectives on the New Age, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1213-X

- Lidke, Jeffrey S. (2005), Interpreting across Mystical Boundaries: An Analysis of Samadhi in the Trika-Kaula Tradition. In: Jacobson (2005), "Theory And Practice of Yoga: Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson", pp 143–180, BRILL, ISBN 9004147578

- Low, Albert (2006), Hakuin on Kensho. The Four Ways of Knowing, Boston & London: Shambhala

- MacInnes, Elaine (2007), The Flowing Bridge: Guidance on Beginning Zen Koans, Wisdom Publications

- Maehle, Gregor (2007), Ashtanga Yoga: Practice and Philosophy, New World Library

- Maezumi, Taizan; Glassman, Bernie (2007), The Hazy Moon of Enlightenment, Wisdom Publications

- Masson, J. Moussaieff; Masson, T.C. (1976), "The Study of Mysticism: A Criticim of W.T. Stace", Journal of Indian Philosophy, 4 (1–2): 109–125, doi:10.1007/BF00211109, S2CID 170168616

- McGinn, Bernard (2006), The Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism, New York: Modern Library

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276

- McNamara (2014), The neuroscience of religious experience (PDF)

- Minsky, Marvin (2006), The Emotion Machine, Simon & Schuster

- Mohr, Michel (2000), Emerging from Nonduality. Koan Practice in the Rinzai Tradition since Hakuin. In: steven Heine & Dale S. Wright (eds.)(2000), "The Koan. texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism", Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Moore, Peter G. (1973), "Recent Studies of Mysticism: A Critical Survey", Religion, 3 (2): 146–156, doi:10.1016/0048-721x(73)90005-5

- Moore, Peter (2005), "Mysticism (further considerations)", in Jones, Lindsay (ed.), MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religion, MacMillan

- Moores, D.J. (2006), Mystical Discourse in Wordsworth and Whitman: A Transatlantic Bridge, Peeters Publishers, ISBN 9789042918092

- Mumon, Yamada (2004), Lectures On The Ten Oxherding Pictures, University of Hawaii Press

- Nakamura, Hajime (2004), A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy. Part Two, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

- Newberg, Andrew; d'Aquili, Eugene (2008), Why God Won't Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief, Random House LLC, ISBN 9780307493156

- Newberg, Andrew and Mark Robert Waldman (2009), How God Changes Your Brain, New York: Ballantine Books

- Nicholson, Andrew J. (2010), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press

- Paden, William E. (2009), Comparative religion. In: John Hinnells (ed.)(2009), "The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion", pp. 225–241, Routledge, ISBN 9780203868768

- Parsons, William B. (2011), Teaching Mysticism, Oxford University Press

- Picard, Fabienne (2013), "State of belief, subjective certainty and bliss as a product of cortical dysfuntion", Cortex, 49 (9): 2494–2500, doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2013.01.006, PMID 23415878, S2CID 206984751

- Picard, Fabienne; Kurth, Florian (2014), "Ictal alterations of consciousness during ecstatic seizures", Epilepsy & Behavior, 30: 58–61, doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.09.036, PMID 24436968, S2CID 45743175

- Presinger, Michael A. (1987), Neuropsychological Bases of God Beliefs, New York: Praeger

- Puligandla, Ramakrishna (1997), Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy, New York: D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd.

- Raju, P.T. (1992), The Philosophical Traditions of India, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

- Rambachan, Anatanand (1994), The Limits of Scripture: Vivekananda's Reinterpretation of the Vedas, University of Hawaii Press

- Renard, Philip (2010), Non-Dualisme. De directe bevrijdingsweg, Cothen: Uitgeverij Juwelenschip

- Sadhu Om (2005), The Path of Sri Ramana, Part One (PDF), Tiruvannamalai: Sri Ramana Kshetra, Kanvashrama

- Samy, AMA (1998), Waarom kwam Bodhidharma naar het Westen? De ontmoeting van Zen met het Westen, Asoka: Asoka

- Sawyer, Dana (2012), Afterword: The Man Who Took Religion Seriously: Huston Smith in Context. In: Jefferey Pane (ed.)(2012), "The Huston Smith Reader: Edited, with an Introduction, by Jeffery Paine", pp 237–246, University of California Press, ISBN 9780520952355

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1844), Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung, 2

- Sekida, Katsuki (1985), Zen Training. Methods and Philosophy, New York, Tokyo: Weatherhill

- Sekida (translator), Katsuki (1996), Two Zen Classics. Mumonkan, The Gateless Gate. Hekiganroku, The Blue Cliff Records. Translated with commentaries by Katsuki Sekida, New York / Tokyo: Weatherhill

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995), "Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience" (PDF), NUMEN, 42 (3): 228–283, doi:10.1163/1568527952598549, hdl:2027.42/43810

- Sharf, Robert H. (2000), "The Rhetoric of Experience and the Study of Religion" (PDF), Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7 (11–12): 267–87

- Shear, Jonathan (2011), "Eastern approaches to altered states of consciousness", in Cardeña, Etzel; Michael, Michael (eds.), Altering Consciousness: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, ABC-CLIO

- Sivananda, Swami (1993), All About Hinduism, The Divine Life Society

- Snelling, John (1987), The Buddhist handbook. A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice, London: Century Paperbacks

- Spilka, Bernard; McIntosh, Daniel N. (1995), "Attribution Theory and Religious Experience." In Ralph W. Hood, Jr., ed., The Handbook of Religious Experience, pp. 421-45., Birmingham, Al.: Religious Education Press

- Spilka e.a. (2003), The Psychology of Religion. An Empirical Approach, New York: The Guilford Press

- Stace, W.T. (1960), Mysticism and Philosophy, London: Macmillan

- Schweitzer, Albert (1938), Indian Thought and its Development, New York: Henry Holt

- Takahashi, Shinkichi (2000), Triumph of the Sparrow: Zen Poems of Shinkichi Takahashi, Grove Press

- Taves, Ann (2009), Religious Experience Reconsidered, Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Underhill, Evelyn (2012), Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 9780486422381

- Venkataramiah, Munagala (1936), Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi, Tiruvannamalai: Sri Ramanasramam

- Waaijman, Kees (2000), Spiritualiteit. Vormen, grondslagen, methoden, Kampen/Gent: Kok/Carmelitana

- Waaijman, Kees (2002), Spirituality: Forms, Foundations, Methods, Peeters Publishers

- Waddell, Norman (2010), Foreword to "Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin", Shambhala Publications

- Wainwright, William J. (1981), Mysticism, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press

- White, David Gordon (ed.) (2000), Tantra in Practice, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-05779-6

- White, David Gordon (2012), The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780226149349

- Wilber, Ken (1996), The Atman Project: A Transpersonal View of Human Development, Quest Books, ISBN 9780835607308

- Wright, Dale S. (2000), Philosophical Meditations on Zen Buddhism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Om, Swami (2014), If Truth Be Told: A Monk's Memoir, Harper Collins

- Yen, Chan Master Sheng (1996), Dharma Drum: The Life and Heart of Ch'an Practice, Boston & London: Shambhala

- Zaehner, R. C. (1957), Mysticism Sacred and Profane: An Inquiry into some Varieties of Praeternatural Experience, Clarendon

- Zaehner, R. C. (1974), Our Savage God: The Perverse Use of Eastern Thought, Sheed and Ward

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1948), De weg tot het Zelf. Leer en leven van de Indische heilige, Sri Ramana Maharshi uit Tiruvannamalai, 's Graveland: Uitgeverij De Driehoek

Web-sources[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Katz, Steven T. (1978), "Language, Epistemology, and Mysticism", in Katz, Steven T. (ed.), Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis, Oxford university Press

- Forman, Robert K., ed. (1997), The Problem of Pure Consciousness: Mysticism and Philosophy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195355116

- Taves, Ann (2009), Religious Experience Reconsidered, Princeton: Princeton University Press

External links[edit]

Robert Taylor

Robert Taylor