2022/06/28

New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) = reasons why it is best Bible trans...

2022/04/02

A Quaker Perspective on the Qur’an and the Bible – Quaker Theology

A Quaker Perspective on the Qur’an and the Bible

By Anthony Manousos

Quaker Theology > Issues > Issue #14, Fall-Winter 2007-2008 > A Quaker Perspective on the Qur’an and the Bible

George Bernard Shaw once observed that England and America are two countries separated by a common language. It could also be said that Christianity, Islam and Judaism are three religions separated by a common religious heritage. The three great monotheistic faiths all claim Abraham as their common spiritual ancestor. They ascribe to many of the same religious narratives and honor many of the same prophets. They worship one God who is the ruler of the universe. Nonetheless, acrimonious and sometimes bloody disputes have arisen among these self-styled “children of Abraham.”

During our current age of religious conflict, scriptures are cited to justify everything from war and terrorism to peacemaking and social justice. It is important for people of faith, as well as for skeptics, to have a basic understanding of what the Bible and the Qur’an actually say and how they are being interpreted from a variety of theological/philosophical perspectives.

In this essay, I will explore some of some areas of controversy regarding the Bible and the Qur’an, including the nature of God (“Do Muslims, Jews, and Christians worship the same God?”), how these scriptures were composed, and how the ambivalence towards war and peace found in these texts reflects the different levels of spiritual development. I am not trained as a biblical or qur’anic scholar, but I have had scholarly training in English literature and have read the Bible and the Qur’an for many years on a daily basis as part of my spiritual practice. I have also written a pamphlet about “Islam from a Quaker Perspective” and pondered what scholars have written about both these scriptures.

In this essay, I will sum up some of what I have learned and offer some reasons why Friends and others who care about peacemaking in the modern (or postmodern) world would do well to increase their scriptural literacy by reading both the Bible and the Qur’an.

I realize that many unprogrammed Friends, like many Americans, are “biblically illiterate.” Hence the Quaker joke:

What do Quakers from Friends United Meeting [the branch of Quakers known for being mainstream Christians] bring to their bible study class? Answer: A Bible and a cup of coffee.

What do liberal, unprogrammed Friends bring to their bible study class? Answer: a cup of coffee.

Joking aside, there are signs of growing interest in the Bible even among liberal Friends. Friends General Conference, the national gathering of liberal Friends, has bible studies in each of its Gatherings and publishes some of the talks given by speakers at these events. Another hopeful indication has been the recent publication of The Quaker Bible Reader, a collection of essays by Friends from different branches of Quakerism. I was also encouraged to learn that some Meetings (such as Orange County Meeting here in California) are making an effort to study the Qur’an.

As a Quaker interested in peacemaking and spirituality, I see three primary reasons to study the Judaeo-Christian-Islamic scriptures:

Knowledge of scripture helps us to be more clear and effective when we dialogue with “people of the book,” i.e. Christians, Muslims, and Jews. Such knowledge is essential if you believe (as I do) that interfaith dialogue plays an important role in post 9/11 peace and reconciliation work.

Scriptural literacy helps us to discern when people are misusing their scriptural tradition either out of ignorance or because of a political agenda. Americans have been described as “Christ-haunted” and “biblically illiterate” which is sad but true, and a source of many problems in today’s world. Many Muslims and Jews also lack direct knowledge of scriptures, either their own or those of other faiths; they rely instead on second-hand opinions that sometimes create misunderstanding and mistrust. To counteract ignorance and religious prejudice, we need to study and to share what we know to be accurate and true about the scriptures. Early Friends knew their scripture intimately and did not hesitate to argue against what they saw as “errors.” George Fox was knowledgeable enough about the Qur’an to quote it authoritatively when writing a letter to the Sultan of Turkey calling for humane treatment of sailors captured by the Turks.

The Bible and Qur’an are sources of genuine spiritual wisdom which, if read with discernment, sensitivity, and intelligence, can help transform our lives. Friends were among the first Christians to recognize divine wisdom not only in the Bible but also in the Qur’an.

It is no easy task to become scripturally literate or to “read the scriptures in the spirit in which they were written” (to use the Quaker phrase). It takes many years of study, and a willingness to keep as open mind as well as a critical spirit.

Quakers and the Bible

Let’s begin by briefly describing how Friends view the Bible, their primary scriptural heritage. Like most 17th century Protestants, early Friends read the Bible incessantly and were steeped in its language and imagery practically from birth. It has been said that if all the Bibles in England were destroyed, George Fox would have been able to reconstruct the Bible from memory. If this story were literally true, Fox would be a Christian version of what Muslims call a hafiz (someone who has memorized the entire Qur’an and can recite it by heart).

Even though Friends read and quoted the Bible as much as any Protestant sect, they differed from most Protestants because they did not see the Bible as the primary source of authority. Instead, Quakers believed that they could have direct access to the Divine through prayer and meditation. In Fox’s view, the Bible was not the “Word of God” the ultimate authority but simply the words of God. The Word of God was the living, inward Christ who could be experienced directly without the intermediary of priest or book. Once someone received a genuine religious insight from this Source, he or she usually found it confirmed in the Bible. George Fox described this process of coming to experience and verify the Truth in his Journal:

Now the Lord God opened to me by his invisible power how that every man was enlightened by the divine light of Christ. I saw that the grace of God, which brings salvation, had appeared to all men, and that the manifestation of the spirit of God was given to every man, with which to profit. These things I did not see by the help of man, nor by the letter, though they are written in the letter; but I saw them in the light of the Lord Jesus Christ, and by his immediate spirit and power, as did the holy men of God by whom the holy scriptures were written.Yet I had no slight esteem of the holy scriptures, they were very precious to me; for I was in that spirit by which they were issued; and what the Lord opened in me, I afterwards found was in agreement with them.

Given this emphasis on direct experience of the Divine rather than on scripture, it is not surprising that Quakerism has produced few eminent Bible scholars. In the 20th century, serious biblical exegesis has been attempted by only a relatively small numbers Quaker academics, such as Henry Cadbury, Rufus Jones, Douglas Steere, Howard Brinton, and Elizabeth Watson. Of these, only Henry Cadbury played a significant role in modern biblical scholarship.

Today the Bible is read by liberal Friends as a source of spiritual inspiration and moral instruction, but it is not seen as an inerrant or infallible source of authority. Friends tend to be drawn to the Jesus Seminar and to theologians like Marcus Borg who combine an historical reading of scripture with a progressive social agenda.

The Evangelical vs. Liberal Perspective on Other Religions

Before going any further with this discussion, it is important to clarify differences between the liberal and Evangelical Quaker approach to other religions. Let’s begin with a brief summary of a complex historical narrative. When Quakers moved westward in the 19th century, many were influenced by the evangelical revival that was sweeping the country. During this tumultuous period western Quakers split into two opposing branches: the evangelicals and the liberals.

Evangelical Quakers were bible- as well as Christ-centered and accepted most of the doctrines of traditional Christianity, most particularly, the notion that you had to accept Jesus Christ as your personal savior or you would go to hell. Evangelical Quakers identified themselves primarily as Christians, and only secondarily as Quakers.

Liberal Quakers took a very different path. They turned towards a more mystical, universalist approach to their faith and welcomed into their fold Jews, Buddhists and “refugees” from doctrinaire Christian faiths who were looking for a non-dogmatic approach to religion. Today most liberal Friends are universalist rather than Christian in outlook.

This profound difference is illustrated by two books about Islam that were published by Friends in the West after 9/11/2001. As a liberal Friend, I wrote a pamphlet called Islam from a Quaker Perspective to explain Islam to Quakers, and to explain Quakerism to Muslims. It was a deeply personal essay, the result of my decision to fast during Ramadan as a way to understand the Muslim faith and practice from a spiritual perspective. This pamphlet was co-published in 2003 by Friends Bulletin (the magazine that I edit for Western Friends) and Quaker Universalist Fellowship. It was re-printed the following spring by the Wider Quaker Fellowship and sent out to around 4,000 subscribers in 103 countries. This pamphlet makes no effort to convert Muslims to Quakerism; that would be unthinkable for liberal Friends.

During this same period, Barclay Press, an Evangelical Quaker publishing house located in Newberg, Oregon, published a book called My Muslim People by Dr. Abraham Sarker, a Muslim convert to Christianity who (as far as I know) is not a Quaker. The purpose of this book is to equip evangelical Christians with the knowledge and tools they need to “save” Muslims from their “false” religion. Sarker was born a Muslim in Bangladesh and trained to become a Muslim missionary with hopes of converting Americans to the “true faith.” But while in America, he dreamed that he was “burning in a lake of fire” and was told by God in an “audible voice” that he should “Go, and get a Bible.” When he did so, he found Christ (thanks to some help from a friendly American evangelist named Peter) and became a Christian.

Sarker describes how his conversion led to his being rejected by his family and persecuted by the Muslim community. With a convert’s zeal, he discusses the shortcomings of Islam and explains why Christianity is the “only hope” for Muslims.

In spite of his proselytizing zeal, Sarker tries to be as accurate as possible in presenting the Islamic faith. He makes it clear that in order to convert a Muslim from his “errors,” you need to know the facts about his religion. Despite its biases, Sarker’s book is a “must read” for anyone who wants to understand an Evangelical Christian perspective on Islam. This book is also indicative of how many (but not all) Evangelical Quakers feel about Islam.

One more point needs to be clarified: not all Christ-centered Friends are exclusivist in their outlook and believe that you must accept Christ to please God and avoid going to hell. It is possible to be a devout Christian Quaker and at the same time respectful and open to Islam, Judaism and other faiths.

To cite an example, Michael Birkel, a professor of religion at Earlham College and a member of Friends United Meeting, approaches Quakerism from a deeply Christian perspective and is also very open to interfaith dialogue with Muslims. In his recent Plenary Address at Ohio Valley Yearly Meeting he writes with great sensitivity and insight about the importance of interfaith dialogue with Muslims. He concludes:

We should not expect agreement, nor victory after all, it’s not a contest. Instead we might find the common ground that comes of listening. We might experience growing respect, despite conflict and challenge. Maybe you and your conversation partners will come to agree on how to disagree. Articulating that “how” can be wonderfully liberating, even exhilarating. Misunderstanding can be an opportunity to learn rather than a reason to be offended. That requires a kind of generosity based in trust.

You might discover a new dimension of what it means to love your neighbor. Like John Woolman’s experience, we can find that our first motion, our motivation, is love, and from there we can be genuinely open to others while being faithful to what is truest in our own tradition.

Birkel’s words would no doubt resonate with Marshall G.S. Hodgson (1922 – 1968), a professor at the University of Chicago who was one of this century’s major Islamic scholars. A practicing Quaker, Hodgson had a deep respect for other cultures and civilizations and challenged the Eurocentric view of history prevalent in his time. In his preface to his magisterial study, The Venture of Islam, Hodgson offers a quotation from John Woolman that epitomizes the perspective of liberal Friends:

To consider mankind other than brethren, to think favours are peculiar to one nation and exclude others, plainly supposes a darkness of understanding.

Do Christians and Muslims Worship the Same God?

Before discussing scriptures, I would like to focus our attention on God since God is considered the revealer of scriptures, as well as their main subject, by all three Abrahamic faiths. A question that has often been posed lately is: do Jews, Muslims and Christians worship the same God? As we shall see, this question has arisen for reasons that have more to do with politics than theology.

Ever since President George Bush stated after 9/11/2001 that Muslims, Christians and Jews worship the same God, many right-wing Christians taken exception with the President’s effort to be pluralistic and conciliatory. Some have gone so far as to describe the “Muslim god” as the antithesis of the “Christian God,” or even an “idol.” Ted Haggard, former President of the National Association of Evangelicals (and now under a cloud because of his secret homosexual liaisons), stated:

The Christian God encourages freedom, love, forgiveness, prosperity and health. The Muslim god appears to value the opposite. The personalities of each god are evident in the cultures, civilizations and dispositions of the peoples that serve them. Muhammad’s central message was submission; Jesus’ central message was love. They seem to be very different personalities.

Richard Land, a top official of the Southern Baptist Convention, cited the Bible to justify this claim: “The Bible is very clear about this. There is only one true God and His name is Jehovah, not Allah.”

Haggard and Land were articulating a common view among evangelicals. In a poll of evangelical leaders at the community level, 79 percent disagreed with the statement that Muslims and Christians “pray to the same god.”

More ominously, General William G. Boykin, a born-again Christian who sees U.S. military exploits in apocalyptic terms, stated: “I knew that my God was bigger than his [i.e. Osman Otto, a Muslim warlord]. I knew that my God was a real God and his was an idol.”

The view that God and Allah are different entities is the result of linguistic as well as theological misunderstanding. English-speaking Muslims often use the Arabic word “Allah” (“the God”) when referring to the supreme deity. The same word is used by Arab-speaking Christians and Jews when referring to God. Furthermore, calling “Allah” an idol invented by Muslims makes no theological sense. Muslims consider idol worship, including portraying God by any sort of image, to be shirk (i.e. idolatry), which an unpardonable sin by Islamic standards.

A deeper question involves discerning whether the Muslims, Christians and Jews share the same basic understanding of God. In 2004 The Christian Century, a magazine for liberal Christians, ran a series of five articles in which leading Christian theologians addressed this question, and then a Muslim scholar named Umar F. Abd-Allah was given a chance to express an Islamic perspective.

In addressing the question of Islam’s understanding of God, Prof.. Abd-Allah (whose name means “Servant of God) explored its social and political context. Why are Muslims being singled out and asked whether they worship the same God as do Christians and Jews? From a Muslim viewpoint, the answer is obvious, and indeed, self-evident. There is only one God. According to the Qur’an, Muslims are required to believe that they worship the same God as did Abraham, Moses and Jesus.

But the Muslim scholar then raised a deeper question: do all Christians or Jews or Muslims share a common understanding of God?

When focusing on the diversity of religious predicates, we might ask: “Does anyone worship the same God?” Can any faith or its followers sport an essentialist label? Which religion can claim to have held a monolithic theological view even within its creedal schools? Hillel and Shammai the sagely Pharisaic “pair” sat together at the head of the Great Sanhedrin but posited sharply divergent visions of God’s character and actions. The Alexandrian Fathers and their counterparts in Antioch were not always affectionately immersed in Christian fellowship. For that matter, earlier Jews and Christians not only differed from their Hellenistic brethren on how they viewed God and Christ but held jarringly different notions of the basic structure of reality.

Re-framing this question in this way opens up an entirely different perspective. It becomes clear that each believer has a different view of God, depending on his or her stage of spiritual/psychological development and/or theological perspective.

In today’s world, the theological boundary is not between Muslims and Christians, or even Muslims and Jews. Rather it is between competing understandings of God. This becomes clear if we consider Prof Abd-Allah’s question in contemporary terms: Do Christians such as Jim Wallis, Marcus Borg, Pat Robertson and Ted Haggard all worship the same God?

My own Quaker-influenced understanding of God is closer to that of Muslims and Jews in the peace movement than it is to fundamentalist Christians who support war. (Both positions have scriptural warrant, as I will explain later.) Furthermore, many fundamentalist Christians and extremist Muslims share a similarly exclusivist and possessive view of God (i.e. “my God is better, bigger, stronger than your God”). This view of God is one that progressive Muslims, Christians and Jews find repellent, or at least immature.

To conclude this brief overview of how different faith traditions view God, it is worth noting that many Muslims would strongly object to the claim that Islam portrays God/Allah as stern and cruel being who demands to be obeyed unquestioningly. With the exception of one, all 114 chapters of the Qur’an begin with the phrase: “In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.” Mercy, compassion and forgiveness are among the most commonly mentioned attributes of God in the Qur’an. In one of the sayings (hadith) of the Prophet Muhammad we are told that “God is more loving and kinder than a mother to her dear child.” Most Muslims as well as most Christians and Jews believe in a God that is compassionate and forgiving as well as peaceful and just.

Composition of the Bible and Qur’an

The Bible and the Qur’an derive from a common religious tradition and express similar spiritual verities, but they were composed under strikingly different circumstances.

The Bible (the Greek word meaning “The Book”) consists of two parts, the “Old” (Hebrew) and the “New” (Christian) Testament (or Gospels). The Hebrew Bible (known to Jews as Tanakh) is actually a series of 39 (or 46, depending on the version) books or writings compiled from 1000-660 BCE [before the Common Era]. The New Testament was composed by a variety of writers between 60 to 110 CE. The contents of the New Testament were formalized by Athanasius of Alexandria in 367 CE, and finally “canonized” (officially authorized) in 382 CE.

Some Christians and Jews believe that everything in the Bible is literally true. Some Christians believe that the Bible has one unifying message, pointing to Christ. Other Christians and Jews see the Bible as a multivocal and polysemous source of Divine wisdom composed by a variety of human authors and reflecting a diversity of meanings and religious perspectives. Efforts to view the Bible, or even the New Testament, as a unified whole have proven problematic at best.

In considering the composition of scripture, at least two issues need to be considered:

1) How were the scriptures composed? Who composed them, when, and for what reason? Is the text we have what the original author(s) wrote or said, or has it been altered over time?

Determining the answers to these questions is extremely difficult. Traditionalists believed that the scriptures were written by the authors whose names are given in the scriptures, e.g. the first five books of the Bible were composed by Moses, the gospel of Matthew was written by the apostle Matthew, etc. Traditionalists also believe that the scriptures have been preserved verbatim and therefore can be seen as “inerrant.”

Beginning in the 18th century, many scholars have come to question these traditional accounts for textual and historical reasons. Close readings of scriptures revealed many stylistic discrepancies showing that these works were written by numerous individuals over a period of many years, and for complex theological reasons.

2) How did certain scriptures become “canonized,” i.e. officially recognized? In the first two centuries after the death of Jesus dozens of “gospels” and epistles attributed to the apostles were written, including the gospels of Mary Magdalene, Thomas, and Peter; the Epistle of Barnabas; the Acts of Andrew and John; the Revelation of Peter, etc. All of these works were rejected by the Church for various reasons. How did certain gospels come to be considered “canonical” (i.e. fit for use by the church) and others rejected as inauthentic or heretical?

These questions have preoccupied Christian scholars for the last couple of centuries.

So far, however, most Muslim scholars have not grappled with questions such as these because the Qur’an is assumed to have always been a unified work directly inspired by God. The Qur’an (meaning “Recital”) consists of 144 suras, or chapters, that were revealed to one man, Mohammad, over a 22-year period, from 610 CE until shortly before his death in 632 CE. As a result, the Qur’an is a much more unified work than the Bible, although some apparent contradictions and inconsistencies have been noted and will be discussed later.

Twenty years after the Prophet’s death, in 653 CE, the first “authorized” version of the Qur’an was compiled under Caliph Uthman. The earliest manuscripts of the Qur’an date back to around 100 years after the Prophet’s death. Most Muslims believe that every word in the Qur’an is an exact transcript of what God revealed to Mohammed, with absolutely no changes in wording since it was first transmitted and written down. Today only fundamentalist Jews or Christians would make such a claim about their Scripture.

Controversies Regarding the “Canonization” of the Qur’an

Some modern non-Muslim scholars have questioned whether the Qur’an was preserved perfectly, word-for-word, as Mohammad received and recited it. Since we do not have an “authorized” version of the Qur’an dating back to the Prophet’s lifetime, we will never know for sure, just as we will never know for certain what happened after the crucifixion of Jesus. We are told that the Prophet’s revelations came in fragmentary outbursts that were copied down and memorized by believers. After his death, these fragments were gathered together into a unified work through a process that has never fully been explained or understood. Caliph Uthman is supposed to have authorized Muslim religious leaders to gather these different versions and produce a standardized text. However, some modern scholars, such as the archeologist Arthur Jeffrey, believe that there were “wide divergences” among these early quranic texts:

When we come to the accounts of ‘Uthman’s recension, it quickly becomes clear that his work is no mere matter of removing dialectical peculiarities in reading, but was a necessary stroke of policy to establish a standard text for the whole empire – there were wide divergences between the collections that had been digested into Codices in the great Metropolitan centres of Medina, Mecca, Basra, Kufa and Demascus. Uthman’s solution was to canonize the Medinan Codex and order all others to be destroyed. There can be little doubt that the text canonized by Uthman was only one among several types of text in existence at the time.

This passage is quoted by the ex-Muslim Christian convert Sarker with great satisfaction, since any suggestion that the text of today’s Qur’an is not exactly as Mohammmad received it would undermine the Muslim claim that the Qur’an is a “perfected” scripture while the scriptures of the Jews and Christians were added to and corrupted over time.

However, there is no scholarly consensus about the significance and extent of variations in Qur’anic texts prior to Uthman. Most secular scholars tend to agree with the traditional view of Islamic scholars that the Qur’an was revealed to Mohammad in its entirety and redacted into its present form during the reign of Uthman.

Some “iconoclastic” scholars, such as John Wansbrough and his students Michael Cook and Patricia Crone, have questioned whether the Qur’an as we know it was revealed in its entirety to Muhammad, since the earliest surviving copies of the complete Qur’an date back to around a hunderd years after the Prophet’s death. These iconoclasts argue that the original Qur’an was expanded and altered as the Islamic empire evolved.

It should be noted, however, that some Muslims question the motives of these secular scholars. As we have seen, those who are seeking to discredit Islam (such as Sarker) use this scholarship to undermine faith in the Qur’an as an inspired text. For centuries Christian scholars have argued that the Qur’an is a forgery, a plagiarism of Christian and Jewish sources, etc. In an article entitled “The Great Koran con trick” Martin Bright examines the pros and cons of this new scholarship. Bright makes it clear that Patricia Crone has a dark view of Islam as religion. According to Bright:

In Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam, Crone argued that the early Muslim converts turned to Islam because it promised an Arab state based on conquest, rape and pillage. “God could scarcely have been more explicit. He told the Arabs that they had a right to despoil others of their women, children and land, or indeed that they had a duty to do so: holy war consisted in obeying.”

Bright notes that Ziauddin Sardar is one of the few Muslim intellectuals to have responded to these new iconoclastic scholars:

[Sardar] has called their work: “Eurocentrism of the most extreme, purblind kind, which assumes that not a single word written by Muslims can be accepted as evidence”. Writing in the aftermath of the Rushdie affair, Sardar placed the western revisionists firmly in the post-colonial orientalist camp, from where colonial “experts” have consistently told Muslims that they know best about the origins of their primitive, barbarian religion. “The triumphant conclusion of Crone and Cook,” he says, “was that Islam is an amalgam of Jewish texts, theology and ritual tradition.”

Whatever the merits of the new scholarship, it is clear that politics played a role in the canonization of Islamic scriptures as well as of the Christian gospels. Politics may play a role even in “objective” scholarship.

It is also clear that the divergences between versions of the Qur’an were not as wide as those between versions of the Christian gospel. In his recent book Constantine’s Bible, David L. Dungan points out that dozens of Gospels were composed in the first couple of centuries after the death of Jesus. One of the tasks of Eusebius (and the Catholic Church) was to winnow this plethora of gospels down to four. This process took place immediately prior to and during the time of Constantine for political as well as theological reasons so that the Church (and the Roman empire) would have a unified scripture and so that theological dissent could be suppressed. Uthman may have had a similar intention, but his job was much simpler since there was only one Qur’an and the discrepancies, if any, were probably minor.

Another controversy regarding the Qur’an involves the Satanic Verses (which Salman Rushdie used as a theme in his book of the same name). According to one of Mohammad’s biographers, Ibn Ishaq, the Prophet wanted so much to please his opponents in Mecca that God supposedly sent him verses implying it was acceptable to seek intercession from certain popular idols such as al-Hat, al-Uzza and Manat. Mohammad allegedly confessed later that it was Satan, not God, who had inspired him to promulgate these verses and they were retracted.

Almost all modern Islamic scholars reject this story as historically improbable and lacking the kind of corroboration required to be considered an authentic haddith (or saying) of the Prophet. Others have said that it doesn’t really matter if Mohammad was tricked by Satan since he was human, and therefore fallible; what matters is that God corrected his mistake and it doesn’t appear in the Qur’an today.

Because scriptures play such an important role in the faith development of “people of the book,” such disputes are inevitable. The wisest approach is to be aware of these controversies and not to let them blind us to the insights and wisdom that we can acquire from a careful and sensitive reading of scripture. Augustine affirmed that the goal of the religious life is to practice “faith, hope, and love.” A person who “keeps a firm hold upon these [virtues], does not need the Scriptures except for the purpose of instructing others” (Dungan, p. 135). Most liberal Quakers, as well as many Muslims, Christians, and Jews, would probably agree with Augustine on this point.

Translation and Politicization of the Scriptures

Muslims believe that the Qur’an cannot be translated because the Arabic of the Qur’an is divinely inspired and too beautiful to be rendered into another language. Therefore, any rendering of the text into another language is considered an interpretation, not a translation.

The same might be said about translations of the Bible: each one is an interpretation, not simply a word-for-word rendering of the text. Each of the many Bibles that I own has a different interpretive perspective. My Catholic Bible contains commentary that accepts textual-historical criticism and promotes a Catholic take on the Gospels (complete with pictures of the stations of the cross). The language of this Catholic version is modern and very readable. My conservative Protestant Bible rejects textual-historical criticism and sees the Bible as the inerrant word of God. It uses the King James translation which conservative Christians seem to favor as if it were authorized not by a self-serving King but by God Himself. My Jubilee African-American Bible offers an African-American perspective on faith and social justice. This version uses plain, modern English that can be read aloud with great effect.

A similar diversity of perspectives can be found among different translations-interpretations of the Qur’an. But unlike Christians, Muslims in America today can be penalized for having the “wrong” interpretation of their scripture.

Let me give an example. In my pamphlet Islam from a Quaker Perspective, I recommended a translation/version of the Qur’an by the eminent Muslim scholar Abdullah Yusuf Ali. Recently I was shocked, but not surprised, to learn that this version has been banned from school libraries in Los Angeles because of its alleged anti-Semitism.

I learned about this through CAIR Watch (www.CAIRwatch.org), a website devoted to exposing the alleged terrorist tendencies of a moderate Islamic organization called the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR). Headquartered in Washington, D.C., with 32 regional offices and chapters in the U.S. and Canada, CAIR was founded in 1994 as a Muslim civil liberties and advocacy group.

CAIR has successfully formed a partnership with the National Council of Churches and held dialogue with representatives of the National Association of Evangelicals. But it is viewed with suspicion by groups that accuse it of supporting Palestinian terrorism. The motto of CAIR Watch is “Keeping an Eye on Hate.”

Because CAIR Watch uses techniques employed by Steven Emerson and others who see Islam as the embodiment of evil and part of a vast conspiracy to dominate the world, it is worth examining how this group exposes CAIR’s alleged anti-Semitism:

According to this website,

In February of 2002, Los Angeles city school officials pulled more than 300 copies of The Meaning of THE HOLY QURAN from area school libraries. The Quran – an English translation published by Maryland-based Amana Publications – was found to have had numerous anti-Jewish commentaries contained within it. One of the cited commentaries read, “The Jews in their arrogance claimed that all wisdom and all knowledge of Allah was enclosed in their hearts. Their claim was not only arrogance but blasphemy.”Doug Smith, Henry Weinstein and Teresa Watanabe, Los Angeles Times, ‘Schools Remove Donated Books,’ February 7, 2002

This commentary by Yusuf Ali is quoted accurately and paraphrases what the Quran actually says. It should be noted that the Quran’s attitude towards Jews is a complex one. The Quran pays tribute to the Jews for being monotheistic and “people of the Book.” It celebrates Jewish prophets like Abraham, Moses, Joseph, etc. But it also criticizes Jews for imagining that they are a “Chosen People” who have a monopoly on God or scriptures. Whether this criticism is anti-Semitic depends on your definition of the term and your attitude towards Muslims.

Given the large Jewish population in Los Angeles and the tensions that arise because of perceived anti-Semitism, it is not hard to see why the L.A. school officials would remove this Qur’an from its shelves. School boards have banned books for all sorts of reasons that seem strange to those of us who cherish the First Amendment. An illustrated edition of “Little Red Riding Hood” was banned in two California school districts in 1989 because the book shows the heroine taking food and wine to her grandmother. The school districts cited concerns about the use of alcohol in the story.

Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice was banned from classrooms in Midland, Michigan, in 1980 because of its portrayal of the Jewish character Shylock. If alleged anti-Semitism is a criterion for banning books in public schools, the Gospel of John should also be banned. It accuses Jews not of blasphemy and arrogance but of killing Christ – an allegation that has caused far more suffering to Jews than any disparaging words in the Qur’an.

However, the CAIR Watch website uses classic McCarthyite techniques to discredit CAIR through guilt by association and unproven accusations. It notes that this edition of the Qur’an was published by an organization that was under investigation for financing terrorism:

In March of 2002, the editor of this Qur’an, the International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT), had its Virginia offices raided by the FBI, in a probe that targeted 14 businesses accused of financing terrorism. One of the groups IIIT was said to have financed was the World and Islam Studies Enterprise (WISE), the Palestinian Islamic Jihad front run by Sami Al-Arian. (Paul Sperry, World Net Daily, ‘Editor of Koran raided by feds,’ April 12, 2002)

CAIR Watch correctly stated that the offices of IITT were raided, but it doesn’t mention that no arrests were made and no charges proven against it. Raids against Muslim businesses occur fairly frequently and are often a sign of anti-Muslim bias. CAIR Watch mentions Sami Al-Arian, a pro-Palestinian professor who was arrested but has not been convicted by a jury of any crime, even after ten years of intense government scrutiny and persecution. The anti-CAIR website goes on:

Only months after the L.A. ban and IIIT raid, in September of 2002, CAIR began providing American libraries with ‘The Meaning of THE HOLY QURAN’ through its ‘Explore Islamic Culture & Civilization’ project. And in May of 2005, CAIR began a new program whereby the group gave a free copy of the Amana-produced Quran to anyone who asked. (Americans Against Hate, ‘CAIR DISTRIBUTING BANNED QURAN,’ May 26, 2005)

CAIR Watch implies that CAIR distributed the Qur’ans for the express purpose of promoting anti-Semitism, but from what I know about CAIR, I am confident that its purpose was conciliatory, not inflammatory. After the news media revealed that soldiers in Guantanamo had treated the Qur’an in ways considered disrespectful by Muslims, the Muslim community was outraged and some Muslims in other countries resorted to violent protests. Instead of denouncing the US government (and thereby running the risk of inciting a violent reaction here in the USA), CAIR chose instead to give out free Qur’ans.

When Pope Benedict made insensitive remarks about Islam that led some Muslims to react with violence, CAIR denounced the violence and called for American Muslims to donate to Catholic charities responsible for rebuilding Christian churches burned down by irate Muslims. (Destroying any house of God, whether it be a synagogue, church, or mosque, is expressly forbidden by the Qur’an.)

It must be admitted, however, that CAIR left itself open to criticism by distributing this version of the Qur’an. Despite allegations of its anti-Jewish bias, I would still recommend Yusuf Ali’s version of the Qur’an since its commentary is excellent. My recommendation would include a caveat regarding its comments about Jews.

I must also point out that for generations, Christian commentaries on the Gospels celebrated its overt and highly inflammatory anti-Semitic passages. Probably the most glaring example is Mathew 27:25 in which the Jewish crowd is alleged to have shouted to Pilate: “Let [Christ’s] blood be upon us and upon our children.”

This savage and utterly unbelievable self-indictment has been used to justify the murder of countless Jews. Take these comments from no less an eminence than John Wesley, in his Explanatory Notes on the Whole Bible, published in the 1750s and still featured today on the very popular crosswalk.com website:

His blood be on us and on our children – As this imprecation was dreadfully answered in the ruin so quickly brought on the Jewish nation, and the calamities which have ever since pursued that wretched people . . . .

(Crosswalk: http://bible.crosswalk.com/Commentaries/WesleysExplanatoryNotes/wes.cgi?book=mt&chapter=027 )

More concise but of the same sort is the Peoples New Testament commentary of 1891, on the same site:

His blood be on us. That is, let us have the responsibility and suffer the punishment. A fearful legacy, and awfully inherited. The history of the Jews from that day on has been the darkest recorded in human annals. (http://bible.crosswalk.com/Commentaries/PeoplesNewTestament/pnt.cgi?book=mt&chapter=027)

Even many recent commentaries still let this outrage pass: one Catholic commentary merely reports that this is “the evangelist’s commentary on the responsibility for Jesus’ death.” Lutheran and Oxford bible commentaries I consulted simply ignored this passage. [ The New American Bible, Thomas Nelson: NY, 1970. The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Revised Standard Version: Oxford Press, 1963. Concordia Self-Study Bible, New International Version, St Louis, MO: 1984.]

One modern translator of the Gospels who challenges this anti-Semitism is Willis Barnstone. In The New Covenant (Penguin, NY: 2002), Barnstone wisely observes: “This line, ‘Let his blood be upon us and upon our children!’ has given rise to much dispute and skepticism. The Jews in the street are shouting, ‘Let the guilt of his murder be upon us, the Jews, forever.’ On Passover evenings the Jews would be in their houses, celebrating the Passover meal. They would not be in the street asking the Romans to crucify a rabbi, and, had they been, they would not be shouting for crucifixion and at once declaring their guilt forever by shouting for crucifixion” (p. 194-195). For those interested in reading a translation of the Gospels that is sensitive to the “Jewishness” of Jesus and his followers, I highly recommend William Barnstone’s thoughtful translation.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should point out that I have been given two free Qur’ans by CAIR: one by Mohammad Marmaduke Pickthall and one by Mohammad Asad. I was never given one by Abdullah Yusuf Ali. I hope this means that CAIR has stopped distributing the Yusuf Ali’s version of Qur’an, perhaps in response to adverse criticism.

The Ambivalence of Scripture towards War and Peace

As a Quaker, I am loath to admit that the scriptures of Judaism, Christianity and Islam can be used to justify war, even genocide, as well as pacifism. Yet it is undeniable that one of the names of God in the Hebrew Bible is YHVH Tzva’ot, which means “Lord of Hosts,” i.e. of Armies. The significance of this dark side to divinity came home to me most graphically in 1992 when I made my first trip to Israel with a group of clergy. Standing before Jericho, not far from the Mount of Temptation where Jesus spend forty days in the desert, a pastor read the following chilling passage:

When the trumpets sounded, the people shouted, and at the sound of the trumpet, when the people gave a loud shout, the wall collapsed; so every man charged straight in, and they took the city. They devoted the city to the LORD and destroyed with the sword every living thing in it men and women, young and old, cattle, sheep and donkeys (Joshua 6:20-21).

Nothing in any scripture I know equals the blood-curdling horror of this passage. Not only women and children, but even animals were eradicated in the name of the Lord!

The cult of the warrior god has unfortunately not disappeared. Recently former Sephardi chief rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu wrote a letter to Prime Minister Ehud Olmert citing scripture to justify the eradication of Palestinians. He said that if some Palestinians continue to fire Kassam rockets into Israel, Israelis are justified in doing whatever it takes to stop them. “If they don’t stop after we kill 100, then we must kill a thousand,” he said. “And if they do not stop after 1,000 then we must kill 10,000. If they still don’t stop we must kill 100,000, even a million. Whatever it takes to make them stop.”

In the letter, Eliyahu quoted from Psalms 18:32. “I will pursue my enemies and apprehend them and I will not desist until I have eradicated them.” Eliyahu wrote: “This is a message to all leaders of the Jewish people not to be compassionate with those who shoot [rockets] at civilians in their houses.”

Some Muslim clerics use similar passages in the Qur’an to justify the killing of civilians on the grounds that Israel is an armed camp occupying Muslim territory and Palestinians have the right to do whatever it takes to oust their oppressors (“Must Innocents Die? The Islamic Debate over Suicide Attacks” by Haim Malka, Middle East Quarterly Spring 2003).

One of the most notorious verses of the Qur’an is 9:5:

“When the sacred months are over, slay the idolaters wherever you find them. Arrest them, besiege them, and lie in ambush everywhere for them. If they repent and take to prayer and render the alms levy, allow them to go their way. God is forgiving and merciful.” Another one is 47:4-5: “When you meet the unbelievers in the battlefield strike off their heads and, when you have laid them low, bind your captives firmly. Then grant them their freedom or take a ransom from them, until War shall lay down her burdens.”

These are warlike, certainly, but it is worth noting that both passages also include provisions for mercy to captives; there was no such luck for the people or animals in Jericho, or several similar cases in the Bible!

Such bloody interpretations of scriptures are vigorously challenged by Jewish and Muslim moderates as well as by many Christians. Religious moderates condemn terrorism (whether by individuals or by states) and point to other passages in scriptures that call for nonviolence.

In my pamphlet Islam from a Quaker Perspective I note that the “Qur’an imposes strict limitations on the use of violence,” which can be interpreted to require an abstention from all forms of modern warfare:

In Reading the Muslim Mind, Hassan Hathout (a well-respected Muslim leader in the Los Angeles area) observes that the Qur’anic rules of war forbid Muslims from harming houses of worship (non-Muslim as well as Muslim), or even the trees or animals of one’s enemy. Under such stringent rules, it would be morally wrong for a Muslim to crash land into the World Trade Center, or for the US to drop a bomb on Hiroshima or on Afghanistan. Hathout concludes: “Since modern war is so devastating, war itself should cease to be an option in conflict resolutions. War should be obsolete just like slavery!” (p. 102).

Many rabbis active in the peace movement have taken a similar position and have condemned the violence in the Middle East as contrary to the spirit of the Jewish prophets.

What are we to make of these divergences of opinion regarding scriptures? First, we must admit that scriptures do not present a unified, logically consistent viewpoint on war or peace. Scriptures can be used to justify almost any atrocity, including suicide bombing and genocide. They can also inspire us to strive “with all our hearts, strength and mind” for peace and justice.

Which passages we choose to follow, and how we interpret the scriptures, depends a great deal more on our level of spiritual development than on logic.

For this reason, it is difficult, if not impossible, to convince anyone to forsake an ethic of violence and embrace an ethic of peace simply by quoting scriptures (although it is helpful to know the scriptures if you are having a discussion with someone who sees them as authoritative).

Scriptures & Stages of Faith

To understand how people can have totally different understandings of what the scriptures have to say about war and peace, the work of James Fowler has been extremely helpful to me. In training to become a Methodist minister, Fowler studied psychology as well as theology. He was a Professor of Theology and Human Development at Emory University and director of both the Center for Research on Faith and Moral Development and the Center for Ethics until he retired in 2005.

Fowler’s great achievement was to apply the concepts of developmental psychology such as Jean Piaget, Erik Erikson, et al. to faith development. According to Fowler, adults generally progress through the following stages in their faith journey:

Stage 4 – “Synthetic-Conventional” faith (arising in adolescence) characterized by conformity

Stage 5 – “Individuative-Reflective” faith (usually mid-twenties to late thirties) a stage of angst and struggle. Individuals take personal responsibility for their beliefs and feelings.

Stage 6 – “Conjunctive” faith (mid-life crisis) acknowledges paradox and transcendence relating to reality behind the symbols of inherited systems.

Stage 7 – “Universalizing” faith, or what some might call “enlightenment”.

This is a somewhat crude simplification of Fowler’s subtle and complex analysis, but it suggests a useful framework for understanding how our reading of scripture changes during our lives. The notion that our spiritual understanding evolves over a lifetime is of course nothing new. The Apostle Paul wrote in a famous passage from his letter to the Corinthians: “When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child, but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

As adults, most of us no longer read the Bible literally, as we did as children. We no longer accept uncritically what our teachers told us about God and the Bible. We have gone through a period of questioning. We have taken personal responsibility for our beliefs as well as for our actions. We have come to recognize that God, Truth, Reality, etc. is too complex, too subtle, to be reduced to any verbal formulation or to any dogma. As we have encountered a variety of people and life experiences, our understanding of life and the Bible grows more complex. We realize that the Bible uses the language of poetry and paradox to suggest the complexities of the human condition and divine reality.

This maturation process does not happen automatically, however. The stages of faith described by Fowler are associated with periods of life, but do not automatically occur at a certain age. We can get “stuck” at a certain stage and never evolve any further. Stress and crises may cause us to regress to an earlier stage. When we feel threatened and fearful, we often return to conventional, tribalistic modes of thinking and feeling. We then interpret scripture in ways that reinforce the world view of our particular religious or national group.

As we mature and grow in our faith, we not only come to embrace the paradoxical and complex nature of religion (and life), we grew less fearful and more accepting. When passages of scriptures that seem strange to us are explained by an enlightened interpreter whether Jewish, Christian, or Muslim we are less apt to be feel defensive. We “feel where the words come from,” to use John Woolman’s phrase, and sense the wisdom underlying the unfamiliar words.

If we keep an open heart and mind, we may reach the stage that James Fowler describes as “enlightenment” and become “universalizers”:

The rare persons who may be described by this stage have a special grace that makes them seem more lucid, more simple, and yet somehow more fully human than the rest of us. Their community is universal in extent. Particularities are cherished because they are vessels of the universal, and thereby valuable apart from any utilitarian considerations. Life is both loved and held to loosely. Such persons are ready for fellowship with persons at any of the other stages and from any other faith tradition.

This is the spiritual state to which early Friends aspired, and to which we still aspire today. William Penn beautifully described these “universalizers”: “The Humble, Meek, Merciful, Just, Pious and Devout Souls, are everywhere of one Religion; and when Death has taken off the Mask, they will know one another, tho’ the divers Liveries they wear here make them Strangers.”

“The diverse Liveries” we wear are our religious and cultural traditions as well as our unique personalities. We need to respect these differences. We also need to acknowledge the controversial, the discordant elements in scriptures the “ocean of darkness,” to use George Fox’s term but we see beyond them to what George Fox called “the ocean of Light.” Thanks to the interfaith movement, my understanding of scripture has broadened as well as deepened and I can see a little more clearly the Light in each religious tradition and in each human soul.

2021/11/08

윌리엄 틴들 - 위키백과, 우리 모두의 백과사전

윌리엄 틴들

윌리엄 틴들(틴데일)(William Tyndale, 1494년~1536년 웨일스 슬림브리지 출신)은 영국의 종교인이다. 존 위클리프에게 영향을 받아 헬라어를 영어로 성경을 번역한 사람이다. 그는 영어 번역을 위해 독일로 건너가 비밀리에 번역작업을 했으며 기존에는 없던 새로운 단어를 만들기도 했다. 성경을 번역한 죄로 체포되어 1536년 10월6일 화형당했다. 킹 제임스 성경 영어 판의 70%가 틴데일의 성경에 근거한다. 그가 독일로 건너가서 동시대의 사람은 마틴 루터의 활동에 영감을 받은 것은 영국의 개혁운동이 외래의 영향을 통해 이루어진 가장 큰 이유로 이해된다.[1]

영국 캠브리지에는 그의 이름 가진 틴델하우스가 있는데 많은 전문학자들이 연구하고 발표하는 연구소로 유명한 곳이다.

생애[편집]

윌리엄 틴들은 1494년 글로스터에서 태어났다. 1510년 옥스퍼드 대학교에 입학하여 1515년 문학 석사학위를 받은 후 성경을 연구하기 위해 1519년 케임브리지로 옮겼다. 성경 연구를 통해 로마 가톨릭교회의 오류를 발견한 틴데일은 성경의 가르침에 따라 영국을 개혁하고자 하였다. 그는 성경을 "하나님의 말씀, 가장 진기한 보석, 지상에 남아 있는 가장 거룩한 유물이며, 신앙의 안내자요 지침서"라고 주장하였다.

틴데일은 성경 지식을 보급함으로 종교개혁이 가능하다고 믿고, 성경을 영어로 번역하고자 하였다. 그러나 당시에 성경을 번역하거나 일반인들이 읽는 것은 로마 교황청이 엄격에서히 금하는 일로 붙잡힐 경우 화형을 당하게 되었다. 틴들은 이러한 박해와 체포 위협 속에서도 유럽 대륙을 떠돌며, 라틴어가 아니라 히브리어와 그리스어 원전에 의한 번역 작업을 계속해 1526년 영어 신약성서를 완성하고 독일에서 인쇄해 영국으로 보냈다. 틴들은 그 후에도 구약성서 번역 작업을 계속했지만, 1535년 네덜란드에서 성경을 영어로 번역했다는 죄목 때문에 체포되었고, 다음해에 화형을 당한다.[2]

그의 사형 이후 엘리자베스 1세에 의해 영어 번역이 논의되었고 제임스 1세에 이르러 그의 번역을 기초로 한 킹제임스 버전 흠정역 성경이 나오게 되었다.

토머스 모어에 대한 비판[편집]

윌리엄 틴데일은 가톨릭 교회에서 성인으로 추앙받고 있는 토머스 모어를 “예수를 배신한 유다”라며 신랄하게 비판했다. 그는 1531년에 토머스 모어가 쓴 《이단에 관한 대화》를 반박하는 글 《토머스 경의 대화에 대한 응답》을 썼다. 이 책의 여백에다 그는 토머스 모어를 ‘거짓의 교황!’이라고 명시해 놓았다. 틴데일은 토머스 모어가 전통을 성경보다 더 높게 평가한다고 생각했기 때문이었다. 틴데일은 이 책에서 고백성사, 순례, 사죄경, 연옥, 십자가 기둥에 기도하기 등 가톨릭 전례들을 모두 바보스러운 의식과 성사라고 비판했다. 이러한 가톨릭을 옹호하는 모어를 “예수를 배신한 유다”라고 비판했다. 그는 모어가 복음의 진리를 외면하는 이유를 “성직자의 관을 쓴 자들의 도움으로 명예와 높은 자리, 권력과 돈을 얻기 위한 것”이라고 야유했다.

이에 토머스 모어는 분노했고 1532년에 장장 6권으로 된 책 《틴데일의 응답을 논박함》을 펴냈다.이에 끝나지 않고 그는 틴데일과 그 추종자들을 색출해 화형에 처하는데 앞장섰다. 토머스 모어는 틴데일을 교회법으로나 세속법으로 옭아매어 빠져 나갈 수 없게 만들고 틴데일의 추종자였던 ‘작은 빌니’, 틴데일의 책을 영국으로 반입했던 베이필드, 런던의 가죽 상인 존 튜크스베리를 화형시켰다. 그리고 틴데일의 영어성경과 저작들을 가지고 있던 법률가 제임스 베인햄을 잡아 모진 고문과 심문을 가했다. 하지만 그는 모진 고문 앞에서도 틴데일은 나쁜 사람이 아니라고 진술했다. 그는 모진 고문과 협박에도 신념을 철회하지 않았다. 그는 화형대에서도 모국어 성경을 갖는 것은 정당하며, 로마의 주교는 적그리스도이며, 연옥은 존재하지 않으며, 그리스도의 피로 정결하게 되는 것이라고 주장했다. 게다가 하나님께 토머스 모어를 용서하라고 기도까지 하며 화형대에서 처형 당했다.[3]

체포와 처형[편집]

틴데일은 엔트베르펜에서 숨어 살았다. 그는 엔트베르펜에 오기 전 함부르크에서 1529년에 모세 5경을 번역했다. 엔트베르펜에 1년간 숨어 지내다가 영국인 밀고자의 고발로 황제의 대리인에게 붙잡히고 만다. 그는 황제의 법령에 의해 1536년 10월초에 사형을 선고 받았다. “주여, 영국 왕의 눈을 뜨게 하소서!” 라는 마지막 말을 남기고 화형당했다.

일화[편집]

에라스무스의 친구인 윌리엄 버치우스의 말에 따르면 틴데일은 영어를 비롯해 히브리어, 헬라어, 라틴어, 이탈리아어, 에스파냐어, 프랑스어의 7개국어를 할 줄 알며 "그가 어떤 언어라도 모국어처럼 말하는 것을 본다면 매우 놀랄 것이다." 라고 말했다.

동시대의 인물[편집]

- 피에트로 폼포나치 : 이탈리아의 철학자로 이타주의적인 삶을 강조하였다. 이런 르네상스적 가르침은 영국 청교도들의 혐오의 대상이었다.[4]

- 데시데리위스 에라스뮈스: 옥스포드 대학 출신의 당시 가장 영향력있는 학자였다.

- 토마스 빌니 : 영국의 종교개혁의 아버지라고 불리는 최초의 순교자이다. 틴데일에게도 영향을 주었다.[5]

각주[편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다. |

- ↑ Knappen, M. M. (Marshall Mason), 1901-1966. (1970, ©1966). 《Tudor Puritanism : a chapter in the history of idealism》. University of Chicago Press. 4쪽.

- ↑ 오덕교《종교개혁사》(합동신학대학원출판부,P384)

- ↑ “성서, 영어 번역하고 화형당한 영국의 루터 윌리엄 틴데일 (下)” (국민일보). 2012년 1월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Knappen, M. M. (Marshall Mason), 1901-1966. (1970, ©1966). 《Tudor Puritanism : a chapter in the history of idealism》. University of Chicago Press. 5쪽.

- ↑ “영국 종교개혁의 아버지 토마스 빌니”. 2019년 1월 30일. 2020년 1월 18일에 확인함.

ウィリアム・ティンダル

ウィリアム・ティンダル(William Tyndale [ˈtɪndəl], 1494年あるいは1495年 - 1536年10月6日)は、イギリスの宗教改革家で聖書をギリシャ語・ヘブライ語原典から初めて英語に翻訳した人物。はじめはヘンリ8世の好意を得たが、王の結婚に反対して信任を失った。また宗教改革への弾圧によりヨーロッパを逃亡しながら聖書翻訳を続けるも、1536年逮捕され、現在のベルギーで焚刑に処された。その後出版された欽定訳聖書は、ティンダル訳聖書に大きく影響されており、それよりもむしろさらに優れた翻訳であると言われる。実際、新約聖書の欽定訳は、8割ほどがティンダル訳のままとされる。

すでにジョン・ウィクリフによって、最初の英語訳聖書が約100年前に出版されていたが、ティンダルはそれをさらに大きく押し進める形で、聖書の書簡の多くの書を英訳した。

文献[編集]

- デイヴィド・ダニエル(田川建三訳)『ウィリアム・ティンダル ある聖書翻訳者の生涯』勁草書房、2001年1月、ISBN 4326101326

- David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography, Yale University Press, 30 Nov 1994, ISBN 0300061323 / Paperback: 1st Mar 2001, ISBN 0300068808

関連項目[編集]

外部リンク[編集]

| ウィキメディア・コモンズには、ウィリアム・ティンダルに関連するメディアがあります。 |

- William Tyndale's Translation(英語)- Wesley Center Online(アーカイブ )

- The Tyndale Society(英語)- ティンダル・ソサエティー

- WilliamTyndale.com(英語)- Friends of William Tyndale(アーカイブ)

- Tyndale(英語)- Bible-Researcher.com

- William Tyndale quotes(英語)- ThinkExist.com(アーカイブ)

- Works by William Tyndale(英語)- プロジェクト・グーテンベルク

田川訳の伝記に関するもの[編集]

William Tyndale

William Tyndale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1494 |

| Died | c. (aged 42) |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Magdalen Hall, Oxford University of Cambridge |

| Known for | Tyndale Bible |

William Tyndale (/ˈtɪndəl/;[1] sometimes spelled Tynsdale, Tindall, Tindill, Tyndall; c. 1494 – c. 6 October 1536) was an English scholar who became a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation in the years leading up to his execution. He is well known as a translator of the Bible into English, influenced by the works of Erasmus of Rotterdam and Martin Luther.[2]

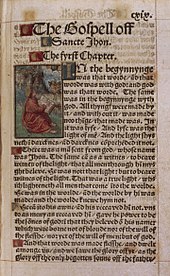

A number of partial English translations had been made from the 7th century onwards, but the religious ferment caused by Wycliffe's Bible in the late 14th century led to the death penalty for anyone found in unlicensed possession of Scripture in English, though translations were available in all other major European languages.[3]

Tyndale worked during a Renaissance of scholarship, which saw the publication of Reuchlin's Hebrew grammar in 1506. Greek was available to the European scholarly community for the first time in centuries, as it welcomed Greek-speaking intellectuals and texts following the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Notably, Erasmus compiled, edited, and published the Greek Scriptures in 1516. Luther's German Bible appeared in 1522.

Tyndale's translation was the first English Bible to draw directly from Hebrew and Greek texts, the first English translation to take advantage of the printing press, the first of the new English Bibles of the Reformation, and the first English translation to use Jehovah ("Iehouah") as God's name as preferred by English Protestant Reformers.[a] It was taken to be a direct challenge to the hegemony of both the Catholic Church and the laws of England maintaining the church's position.

A copy of Tyndale's The Obedience of a Christian Man (1528), which some claim or interpret to argue that the king of a country should be the head of that country's church rather than the Pope, fell into the hands of the English King Henry VIII, providing a rationalisation for breaking the Church in England from the Catholic Church in 1534.[4][5] In 1530, Tyndale wrote The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry's annulment of his own marriage on the grounds that it contravened Scripture.[6] Fleeing England, Tyndale sought refuge in the Flemish territory of the Catholic Emperor Charles V. In 1535, Tyndale was arrested and jailed in the castle of Vilvoorde (Filford) outside Brussels for over a year. In 1536, he was convicted of heresy and executed by strangulation, after which his body was burnt at the stake. His dying prayer was that the King of England's eyes would be opened; this seemed to find its fulfilment just one year later with Henry's authorisation of the Matthew Bible, which was largely Tyndale's own work, with missing sections translated by John Rogers and Miles Coverdale.

Tyndale's translation of the Bible was used for subsequent English translations, including the Great Bible and the Bishops' Bible, authorised by the Church of England. In 1611 after seven years of work, the 47 scholars who produced the King James Bible[7] drew significantly from Tyndale's original work and the other translations that descended from his.[8] One estimate suggests that the New Testament in the King James Version is 83% Tyndale's words and the Old Testament 76%.[9][10] Hence, the work of Tyndale continued to play a key role in spreading Reformation ideas across the English-speaking world and eventually across the British Empire. In 2002, Tyndale was placed 26th in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[11][12]

Contents

Life[edit]

Tyndale was born around 1494[b] in Melksham Court, Stinchcombe, a village near Dursley, Gloucestershire.[13] The Tyndale family also went by the name Hychyns (Hitchins), and it was as William Hychyns that Tyndale was enrolled at Magdalen Hall, Oxford. Tyndale's family had moved to Gloucestershire at some point in the 15th century, probably as a result of the Wars of the Roses. The family originated from Northumberland via East Anglia. Tyndale's brother Edward was receiver to the lands of Lord Berkeley, as attested to in a letter by Bishop Stokesley of London.[14]

Tyndale is recorded in two genealogies[15][16] as having been the brother of Sir William Tyndale of Deane, Northumberland, and Hockwold, Norfolk, who was knighted at the marriage of Arthur, Prince of Wales to Catherine of Aragon. Tyndale's family was thus descended from Baron Adam de Tyndale, a tenant-in-chief of Henry I. William Tyndale's niece Margaret Tyndale was married to Protestant martyr Rowland Taylor, burnt during the Marian Persecutions.

At Oxford[edit]

Tyndale began a Bachelor of Arts degree at Magdalen Hall (later Hertford College) of Oxford University in 1506 and received his B.A. in 1512, the same year becoming a subdeacon. He was made Master of Arts in July 1515 and was held to be a man of virtuous disposition, leading an unblemished life.[17][incomplete short citation] The M.A. allowed him to start studying theology, but the official course did not include the systematic study of Scripture. As Tyndale later complained:

They have ordained that no man shall look on the Scripture, until he be noselled in heathen learning eight or nine years and armed with false principles, with which he is clean shut out of the understanding of the Scripture.

He was a gifted linguist and became fluent over the years in French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, and Spanish, in addition to English.[18] Between 1517 and 1521, he went to the University of Cambridge. Erasmus had been the leading teacher of Greek there from August 1511 to January 1512, but not during Tyndale's time at the university.[19]

Tyndale became chaplain at the home of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury in Gloucestershire and tutor to his children around 1521. His opinions proved controversial to fellow clergymen, and the next year he was summoned before John Bell, the Chancellor of the Diocese of Worcester, although no formal charges were laid at the time.[20][incomplete short citation] After the meeting with Bell and other church leaders, Tyndale, according to John Foxe, had an argument with a "learned but blasphemous clergyman", who allegedly asserted: "We had better be without God's laws than the Pope's.", to which Tyndale responded: "I defy the Pope, and all his laws; and if God spares my life, ere many years, I will cause the boy that driveth the plow to know more of the Scriptures than thou dost!"[21][22]

Tyndale left for London in 1523 to seek permission to translate the Bible into English. He requested help from Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, a well-known classicist who had praised Erasmus after working together with him on a Greek New Testament. The bishop, however, declined to extend his patronage, telling Tyndale that he had no room for him in his household.[23] Tyndale preached and studied "at his book" in London for some time, relying on the help of cloth merchant Humphrey Monmouth. During this time, he lectured widely, including at St Dunstan-in-the-West at Fleet Street in London.

In Europe

Tyndale left England for continental Europe, perhaps at Hamburg, in the spring of 1524, possibly travelling on to Wittenberg. There is an entry in the matriculation registers of the University of Wittenberg of the name "Guillelmus Daltici ex Anglia", and this has been taken to be a Latinisation of "William Tyndale from England".[24] He began translating the New Testament at this time, possibly in Wittenberg, completing it in 1525 with assistance from Observant Friar William Roy.

In 1525, publication of the work by Peter Quentell in Cologne was interrupted by the impact of anti-Lutheranism. A full edition of the New Testament was produced in 1526 by printer Peter Schöffer in Worms, a free imperial city then in the process of adopting Lutheranism.[25] More copies were soon printed in Antwerp. It was smuggled from continental Europe into England and Scotland. The translation was condemned in October 1526 by Bishop Tunstall, who issued warnings to booksellers and had copies burned in public.[26] Marius notes that the "spectacle of the scriptures being put to the torch... provoked controversy even amongst the faithful."[26] Cardinal Wolsey condemned Tyndale as a heretic, first stated in open court in January 1529.[27][incomplete short citation]

From an entry in George Spalatin's diary for 11 August 1526, Tyndale apparently remained at Worms for about a year. It is not clear exactly when he moved to Antwerp. The colophon to Tyndale's translation of Genesis and the title pages of several pamphlets from this time purported to have been printed by Hans Lufft at Marburg, but this is a false address. Lufft, the printer of Luther's books, never had a printing press at Marburg.[28]

Following the hostile reception of his work by Tunstall, Wolsey and Thomas More in England, Tyndale retreated into hiding in Hamburg and continued working. He revised his New Testament and began translating the Old Testament and writing various treatises.[29]

Opposition to Henry VIII's annulment[edit]

In 1530, he wrote The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry VIII's planned annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon in favour of Anne Boleyn, on the grounds that it was unscriptural and that it was a plot by Cardinal Wolsey to get Henry entangled in the papal courts of Pope Clement VII.[30][31] The king's wrath was aimed at Tyndale. Henry asked Emperor Charles V to have the writer apprehended and returned to England under the terms of the Treaty of Cambrai; however, the emperor responded that formal evidence was required before extradition.[32] Tyndale developed his case in An Answer unto Sir Thomas More's Dialogue.[33]

Betrayal and death[edit]

Eventually, Tyndale was betrayed by Henry Phillips[34] to authorities representing the Holy Roman Empire.[35] He was seized in Antwerp in 1535, and held in the castle of Vilvoorde (Filford) near Brussels.[36] Some suspect that Phillips was hired by Bishop Stokesley to gain Tyndale's confidence and then betray him.

He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and was found guilty and condemned to be burned to death, despite Thomas Cromwell's intercession on his behalf. Tyndale "was strangled to death while tied at the stake, and then his dead body was burned".[37] His final words, spoken "at the stake with a fervent zeal, and a loud voice", were reported as "Lord! Open the King of England's eyes."[38][39] The traditional date of commemoration is 6 October, but records of Tyndale's imprisonment suggest that the actual date of his execution might have been some weeks earlier.[40] Foxe gives 6 October as the date of commemoration (left-hand date column), but gives no date of death (right-hand date column).[36] Biographer David Daniell states the date of death only as "one of the first days of October 1536".[39]

Within four years, four English translations of the Bible were published in England at the king's behest,[c] including Henry's official Great Bible. All were based on Tyndale's work.[41]

Theological views[edit]

Tyndale seems to have come out of the Lollard tradition, which was strong in Gloucestershire. Tyndale denounced the practice of prayer to saints.[42] He also rejected the then orthodox church view that the Scriptures could only be interpreted by approved clergy.[43] While his views were influenced by Luther, Tyndale also deliberately distanced himself from the German reformer on several key theological points, including transubstantiation, which Tyndale rejected.[44]

Printed works[edit]

Although best known for his translation of the Bible, Tyndale was also an active writer and translator. As well as his focus on the ways in which religion should be lived, he had a focus on political issues.

| Year Printed | Name of Work | Place of Publication | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1525 | The New Testament Translation (incomplete) | Cologne | |

| 1526* | The New Testament Translation (first full printed edition in English) | Worms | |

| 1526 | A compendious introduction, prologue or preface into the epistle of Paul to the Romans | ||

| 1527 | The parable of the wicked mammon | Antwerp | |

| 1528 | The Obedience of a Christen Man[45] (and how Christen rulers ought to govern...) | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1530* | The five books of Moses [the Pentateuch] Translation (each book with individual title page) | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1530 | The practice of prelates | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1531 | The exposition of the first epistle of saint John with a prologue before it | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1531? | The prophet Jonah Translation | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1531 | An answer into Sir Thomas More's dialogue | ||

| 1533? | An exposicion upon the. v. vi. vii. chapters of Mathew | ||

| 1533 | Erasmus: Enchiridion militis Christiani Translation | ||

| 1533 | The Souper of the Lorde | Nornburg | Niclas Twonson |

| 1534 | The New Testament Translation (thoroughly revised, with a second foreword against George Joye's unauthorised changes in an edition of Tyndale's New Testament published earlier in the same year) | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1535 | The testament of master Wylliam Tracie esquire, expounded both by W. Tindall and J. Frith | ||

| 1536? | A path way into the holy scripture | ||

| 1537 | The Matthew Bible, which is a Holy Scripture Translation (Tyndale, Rogers, and Coverdale) | Hamburg | Richard Grafton |

| 1548? | A brief declaration of the sacraments | ||

| 1573 | The whole works of W. Tyndall, John Frith, and Doct. Barnes, edited by John Foxe | ||

| 1848* | Doctrinal Treatises and Introductions to Different Portions of the Holy Scriptures, edited by Henry Walter.[46] | Tindal, Frith, Barnes | |

| 1849* | Expositions and Notes on Sundry Portions of the Holy Scriptures Together with the Practice of Prelates, edited by Henry Walter.[46] | ||

| 1850* | An Answer to Sir Thomas More's Dialogue, The Supper of the Lord after the True Meaning of John VI. and I Cor. XI., and William Tracy's Testament Expounded, edited by Henry Walter.[46] | ||

| 1964* | The Work of William Tyndale | ||

| 1989** | Tyndale's New Testament | ||

| 1992** | Tyndale's Old Testament | ||

| Forthcoming | The Independent Works of William Tyndale | ||

| Forthcoming | Tyndale's Bible - The Matthew Bible: Modern Spelling Edition | ||

*These works were printed more than once, usually signifying a revision or reprint. However the 1525 edition was printed as an incomplete quarto and was then reprinted in 1526 as a complete octavo. **These works were reprints of Tyndale's earlier translations revised for modern spelling. | |||

Legacy[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Lutheranism |

|---|

|

show

|

show Organization |

show Missionaries |

show Theologians |

Impact on the English language[edit]

In translating the Bible, Tyndale introduced new words into the English language; many were subsequently used in the King James Bible, such as Passover (as the name for the Jewish holiday, Pesach or Pesah) and scapegoat. Coinage of the word atonement (a concatenation of the words 'At One' to describe Christ's work of restoring a good relationship—a reconciliation—between God and people)[47] is also sometimes ascribed to Tyndale.[48][49] However, the word was probably in use by at least 1513, before Tyndale's translation.[50][51] Similarly, sometimes Tyndale is said to have coined the term mercy seat.[52] While it is true that Tyndale introduced the word into English, mercy seat is more accurately a translation of Luther's German Gnadenstuhl.[53]

As well as individual words, Tyndale also coined such familiar phrases as:

- my brother's keeper

- knock and it shall be opened unto you

- a moment in time

- fashion not yourselves to the world

- seek and ye shall find

- ask and it shall be given you

- judge not that ye be not judged

- the word of God which liveth and lasteth forever

- let there be light

- the powers that be

- the salt of the earth

- a law unto themselves

- it came to pass

- the signs of the times

- filthy lucre

- the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak (which is like Luther's translation of Matthew 26,41: der Geist ist willig, aber das Fleisch ist schwach; Wycliffe for example translated it with: for the spirit is ready, but the flesh is sick.)

- live, move and have our being

Controversy over new words and phrases[edit]

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church did not approve of some of the words and phrases introduced by Tyndale, such as "overseer", where it would have been understood as "bishop", "elder" for "priest", and "love" rather than "charity". Tyndale, citing Erasmus, contended that the Greek New Testament did not support the traditional readings. More controversially, Tyndale translated the Greek ekklesia (Greek: εκκλησία), (literally "called out ones"[54][55]) as "congregation" rather than "church".[56][incomplete short citation] It has been asserted this translation choice "was a direct threat to the Church's ancient – but so Tyndale here made clear, non-scriptural – claim to be the body of Christ on earth. To change these words was to strip the Church hierarchy of its pretensions to be Christ's terrestrial representative, and to award this honour to individual worshipers who made up each congregation."[56][incomplete short citation][55]

Tyndale was accused of errors in translation. Thomas More commented that searching for errors in the Tyndale Bible was similar to searching for water in the sea and charged Tyndale's translation of The Obedience of a Christian Man with having about a thousand false translations. Bishop Tunstall of London declared that there were upwards of 2,000 errors in Tyndale's Bible, having already in 1523 denied Tyndale the permission required under the Constitutions of Oxford (1409), which were still in force, to translate the Bible into English. In response to allegations of inaccuracies in his translation in the New Testament, Tyndale in the Prologue to his 1525 translation wrote that he never intentionally altered or misrepresented any of the Bible but that he had sought to "interpret the sense of the scripture and the meaning of the spirit."[56][incomplete short citation]

While translating, Tyndale followed Erasmus's 1522 Greek edition of the New Testament. In his preface to his 1534 New Testament ("WT unto the Reader"), he not only goes into some detail about the Greek tenses but also points out that there is often a Hebrew idiom underlying the Greek.[57] The Tyndale Society adduces much further evidence to show that his translations were made directly from the original Hebrew and Greek sources he had at his disposal. For example, the Prolegomena in Mombert's William Tyndale's Five Books of Moses show that Tyndale's Pentateuch is a translation of the Hebrew original. His translation also drew on the Latin Vulgate and Luther's 1521 September Testament.[56][incomplete short citation]

Of the first (1526) edition of Tyndale's New Testament, only three copies survive. The only complete copy is part of the Bible Collection of Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart. The copy of the British Library is almost complete, lacking only the title page and list of contents. Another rarity is Tyndale's Pentateuch, of which only nine remain.

Impact on English Bibles[edit]

The translators of the Revised Standard Version in the 1940s noted that Tyndale's translation, including the 1537 Matthew Bible, inspired the translations that followed: The Great Bible of 1539; the Geneva Bible of 1560; the Bishops' Bible of 1568; the Douay-Rheims Bible of 1582–1609; and the King James Version of 1611, of which the RSV translators noted: "It [the KJV] kept felicitous phrases and apt expressions, from whatever source, which had stood the test of public usage. It owed most, especially in the New Testament, to Tyndale".

Brian Moynahan writes: "A complete analysis of the Authorised Version, known down the generations as 'the AV' or 'the King James', was made in 1998. It shows that Tyndale's words account for 84% of the New Testament and for 75.8% of the Old Testament books that he translated."[58][incomplete short citation] Joan Bridgman makes the comment in the Contemporary Review that, "He [Tyndale] is the mainly unrecognised translator of the most influential book in the world. Although the Authorised King James Version is ostensibly the production of a learned committee of churchmen, it is mostly cribbed from Tyndale with some reworking of his translation."[59]

Many of the English versions since then have drawn inspiration from Tyndale, such as the Revised Standard Version, the New American Standard Bible, and the English Standard Version. Even the paraphrases like the Living Bible have been inspired by the same desire to make the Bible understandable to Tyndale's proverbial ploughboy.[60][22]

George Steiner in his book on translation After Babel refers to "the influence of the genius of Tyndale, the greatest of English Bible translators."[61] He has also appeared as a character in two plays dealing with the King James Bible, Howard Brenton's Anne Boleyn (2010) and David Edgar's Written on the Heart (2011).

Memorials[edit]

A memorial to Tyndale stands in Vilvoorde, Flanders, where he was executed. It was erected in 1913 by Friends of the Trinitarian Bible Society of London and the Belgian Bible Society.[62] There is also a small William Tyndale Museum in the town, attached to the Protestant church.[63] A bronze statue by Sir Joseph Boehm commemorating the life and work of Tyndale was erected in Victoria Embankment Gardens on the Thames Embankment, London, in 1884. It shows his right hand on an open Bible, which is itself resting on an early printing press. A life-sized bronze statue of a seated William Tyndale at work on his translation by Lawrence Holofcener (2000) was placed in the Millennium Square, Bristol, United Kingdom.