Self-Care to World-Care: Three Examples

JANUARY 2, 2023 BY GUDJON BERGMANN

To influence the world around us, even in minor ways, the real work begins inside and emanates outwards. We don’t need to be perfect to do good deeds in the world, but we must be sincere in our efforts.

If we are in a continual state of discord (i.e., outraged, negative, demanding, judgmental, spiteful, etc.) while we try to promote bridge-building and common ground, we are bound to fail.

To paraphrase Emerson,

‘how people act speaks so loudly that we can’t hear what they are saying.’

For best results, peaceful efforts should come from within, and an alignment of thought, word, and deed is preferable.

From Self-Care to World-Care

Carol Gilligan’s model for moral development shows that human beings generally move from being selfish to being able to care for others in their near environment to, in rare cases, showing genuine care for people they don’t know (here, care is defined as an action, not merely a nice thought).

When we compare her model to others in the same vein—including Piaget, Loevinger, Erikson, Steiner, Beck, Graves, Kohlberg, Peck, Fowler, Wilber, and others—moral growth corresponds with people’s ability to see the world from an ever-increasing number of perspectives and act accordingly; a classification that rhymes with compassion, defined as the sympathetic consciousness of other’s distress together with a desire to alleviate it.

Simply put, moral growth leads to increased compassion and care.

Let’s briefly look at the progression from selfish to care to world-care.

Stage One = Selfish

At stage one, a selfish person can only see the world from his or her point of view. The healthy version of selfishness produces self-care and win-win situations. In contrast, the unhealthy version produces battles and win-lose scenarios, where selfish desires are achieved at other people’s expense. Society has several names for the latter, including narcissism, vanity, egotism, and self-absorption.

Stage Two = Care

At the second stage, care, individuals become generous towards those within their circle of care, including spouses, family, friends, and near-community. A person who has begun caring for another is willing to sacrifice time, energy, and money unselfishly so that another may grow and flourish (M. Scott Peck’s definition of love). The ability to care for others epitomizes the underpinnings of civilized society. Without a tapestry of caring, civilization would collapse into a chaotic every-man-for-himself battlefield.

Stage Three = World-Care

The third stage of development, world-care, is relatively uncommon. It depends on people’s ability to show care (take action) for others they do not know. World-care can start with minor things, such as a genuine willingness to pay taxes for the greater good or reducing personal consumption to curb carbon emissions. However, as empathy grows, people at the stage of world-care will genuinely attempt to care for everyone, often at their own expense.

Expanding the Circle of Care

If individuals want to increase their aptitude for care and compassion, they need to establish self-care and expand their abilities. The most common metaphors are: learn how to swim before you attempt to rescue a drowning person, when pressure falls in an airplane cabin, put the oxygen mask on yourself first and then on your child, you have to earn money before you can give money, and demonstrate love for those who are near you before you attempt to love the entire world.

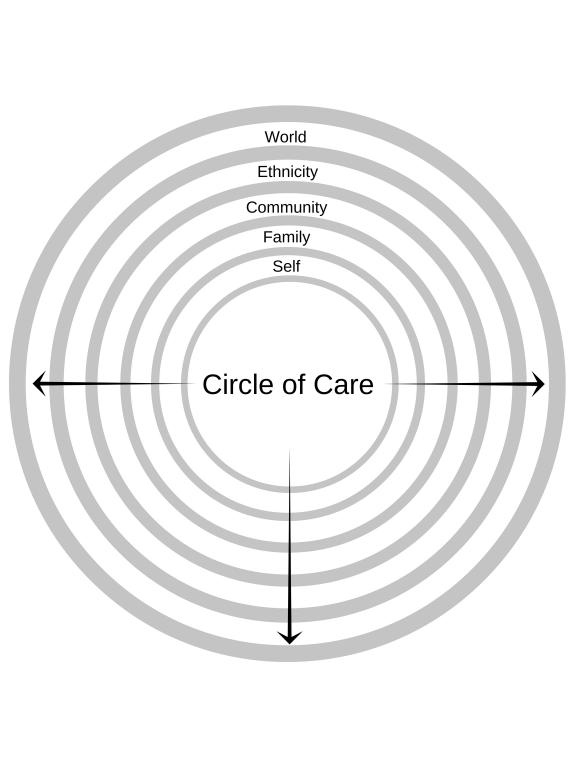

The underlying principle is always the same. Caring is an ability. How can you care for others if you cannot care for yourself? Expanding the circle of care looks something like this:

Each successive circle denotes an increased ability to care for more and more people. Let’s look at three examples of this behavior: Gandhi, Mother Teresa, and Nelson Mandela.

Gandhi: India’s Great Soul

Mohandas Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) was a towering historical figure. He lived his philosophy of nonviolent resistance (satyagraha) to the best of his ability. His approach, which grew into a full-fledged ideology with many specific tenets, was primarily based on acts of self-control, developing peace from within, and standing firm when it came to righteous convictions, never at the expense of others but always at one’s own expense. He preached that satyagrahis should never hate the doer, only resist the action and that no human being was beyond redemption, repeatedly stating that:

“It is easy enough to be friendly to one’s friends. But to befriend the one who regards himself as your enemy is the quintessence of true religion. The other is mere business.”

Gandhi was not beyond reproach as a lawyer, activist, spiritual figure, and politician. Still, looking at his life, one can hardly doubt the sincerity of his convictions nor argue against their effectiveness.

Preparation for South Africa

His road from self-care to world-care began with a spiritual upbringing in India and a legal education in England, both of which became central to his later work. Pride was the seed that flowered into a lifetime of activism. After buying a first-class train ticket via mail, Gandhi was thrown out of his prepaid cabin and off the train merely for being an Indian. That incident so insulted his dignity that he went to work for the civil rights of the Indian community in South Africa. It was there, with inspiration from Thoreau, among others, that he developed his philosophy of nonviolent civil disobedience.

Expanding the Circle

After success in South Africa, Gandhi returned to India and expanded his circle of care to include the Indian people, who quickly bestowed on him the honorary title Mahatma, which means Great (Maha) Soul (Atman). He spent most of his adult life working towards Indian independence at a tremendous personal expense. Sacrifice was really at the heart of his philosophy; the will to suffer until the suffering became unbearable in the eyes of the oppressors.

Peace in the World

Partly thanks to his efforts, India finally gained independence in 1947, one year before his assassination. In the final year of his life, Gandhi felt a deep need to expand his circle of care to include all of the world’s inhabitants and was increasingly worried about world peace, but since his life was cut short, we will never know what kind of work he would have engaged in.

Exceptional and Flawed

Today, Gandhi is a revered historical figure, sometimes to the point of deification (especially in India), but he was simultaneously an exceptional servant of humanity and a flawed human being. He readily admitted to some of those flaws in his autobiography, while other shortcomings have been exposed in the light of modern values.

Spiritual Foundation

What we can surmise from Gandhi’s story is this. Without a modicum of self-care—including a spiritual upbringing and high-quality education—he would not have been prepared to fill his role of service and would likely have failed. Personal pride may have been the instigator of his activism, but he grew into the role and became more selfless every year. His vocation required tremendous sacrifices, especially concerning his family, as Gandhi spent much of his adult life in and out of prison. His expansion was realized step-by-step by living an intentional life focused on service.

Mother Teresa: Nun, Teacher, Mother, Saint

Mother Teresa (1910-1997), born Anjezë Gonxhe Bojaxhiu in Albania, left her home in Albania in 1928 to join the Sisters of Loreto in Ireland and become a missionary. That led her to India in 1929, where she taught at St. Teresa’s School until she experienced “the call within the call” in 1946 when she had been helping the poor while living among them during a retreat. The work for which she is known worldwide began in 1948, and was formally granted permission from the Vatican in 1950 when she founded the Missionaries of Charity. She, along with the sisters in her order, took vows of chastity, poverty, obedience, and wholehearted free service to the poorest of the poor.

Working With the Poor

The first several years of her work were enormously difficult. She had to beg for food and supplies while experiencing loneliness and a yearning for the comforts of convent life. She wrote in her diary:

“The poverty of the poor must be so hard for them. While looking for a home I walked and walked till my arms and legs ached. I thought how much they must ache in body and soul, looking for a home, food and health. Then, the comfort of Loreto [her former congregation] came to tempt me. “You have only to say the word and all that will be yours again,” the Tempter kept on saying … Of free choice, my God, and out of love for you, I desire to remain and do whatever be your Holy will in my regard. I did not let a single tear come.”

Deserve to Die Like Angels

Thanks to her steadfast devotion, the work continued. She founded hospices where people received medical attention and were allowed to die with dignity per their faith. Muslims were read the Quran, Hindus received water from the Ganges, and Catholics received final anointing, all in accordance with Teresa’s belief that no matter their status in life, people deserved to die like angels—loved and wanted.

Expanding Her Reach

By the 1960s, she had opened orphanages, hospices, and leper houses throughout India. In 1965, she expanded her congregation abroad and opened a house in Venezuela with five sisters. Her reach increased with every passing year, and in 2012 her order had over 4500 sisters active in 133 countries and was managing homes for people dying of HIV/AIDS, leprosy, and tuberculosis and operating soup kitchens, dispensaries, mobile clinics, family counseling programs, orphanages, and schools.

As her circle of care grew, Teresa proclaimed:

“By blood, I am Albanian. By citizenship, an Indian. By faith, I am a Catholic nun. As to my calling, I belong to the world.”

Mother Teresa drew praise for her work and an array of criticism—much of which was aimed at her rigid belief structure. She was canonized in 2016. Today she is known within the Catholic Church as Saint Teresa of Calcutta.

Nelson Mandela: The Prisoner Who Kept an Open Heart

Nelson Mandela (1918-2013) was a complicated man. He trained as a lawyer and openly opposed apartheid (a system of segregation in South Africa that privileged whites). In his early years, Mandela was attracted to Marxism and wanted to engage in nonviolent protests, but he crossed the line into sabotage against the government in 1961 out of frustration. That was one of the factors used against him when he was sentenced to life in prison for conspiring to overthrow the government. Nevertheless, his commitment to democracy was evident, even at his trial, where he said:

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to see realized. But if it need be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Decades in Prison

Mandela spent the next twenty-seven years in prison. He wrote his autobiography in secret during that time and garnered support from people all around the world. Outside pressure mounted until he was finally released in 1990.

Refused to Be Consumed

The most remarkable thing about Mandela’s story is that he was not consumed with anger, hate, or a need for vengeance after he was set free. Instead, he worked with his oppressors to end apartheid, ran for president of South Africa, and led an unparalleled racial reconciliation process.

Forgiveness is truly the most miraculous aspect of being human. That was certainly the case for Mandela. Seeking revenge would have been most understandable after everything he went through, but he chose to be a unifier instead. He kept his heart open despite a lifetime of adversity. That won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993.

Global Efforts

After his term as president, Mandela kept on combating poverty and HIV/AIDS through his charitable Nelson Mandela Foundation and worked tirelessly to bring about peace. In a 2002 Newsweek interview, he confessed:

“I really wanted to retire and rest and spend more time with my children, my grandchildren and of course with my wife. But the problems are such that for anybody with a conscience who can use whatever influence he may have to try to bring about peace, it’s difficult to say no.”

Remarkable Role Models

As I have made clear in my writings, I do not believe in perfection. That is why I never put people on pedestals and worship them. Yet, I do see people as role models. I see behaviors that can be replicated.

That is what Gandhi, Mother Teresa, and Mandela are to me. Role models. They weren’t flawless, yet they stepped into the public square—where everyone gets criticized, no matter who they are and what they do—and devoted their lives to caring for others in the best ways they knew how. They showed an ability to stay centered during times of tremendous pressure and overcame periods of grief, doubt, and despair with a devotion to causes larger than themselves. Selfish needs were supplanted by selflessness. When they could have stopped, when they could have retired and thought only of themselves, all four continued to work for the benefit of people they did not know because it was the right thing to do.

When I have challenging days of my own, I often think of them, and that helps me get back on track. I try to emulate their admirable actions and forgive them for their limitations.

* This article was curated from Co-Human Harmony: Using Our Shared Humanity to Bridge Divid

Gudjon Bergmann

Author, Coach, and Mindfulness Teacher

Amazon Author Profile

Recommended books:Monk of All Faiths: Inspired by The Prophet (fiction)

Spiritual in My Own Way (memoir)

Co-Human Harmony: Using Our Shared Humanity to Bridge Divides (nonfiction)

Experifaith: At the Heart of Every Religion (nonfiction)

Premature Holiness: Five Weeks at the Ashram (novel)

The Meditating Psychiatrist Who Tried to Kill Himself (novel)