A Swim in a Pond in the Rain by George Saunders review – rules for good writing, and more

The spell of words ... a wonderful book in which a Booker prizewinner explains what makes classic short stories work so well

This book is a delight, and it’s about delight too. How necessary, at our particular moment. Novelist and short story writer George Saunders has been teaching creative writing at Syracuse University in the US for the last 20 years, including a course in the 19th-century Russian short story in translation. “A few years back, after the end of one class (chalk dust hovering in the autumnal air, old-fashioned radiator clanking in the corner, marching band processing somewhere in the distance, let’s say),” he had the realisation that “some of the best moments of my life, the moments during which I’ve really felt myself offering something of value to the world, have been spent teaching that Russian class.”

I love the warmth with which he writes about this teaching, and agree wholeheartedly that there’s not much on earth as good, if you’re that way inclined, as an afternoon spent discussing sublime fiction with a class of eagerly intelligent apprentice writers, saturated in the story and greedy for insight and understanding (everyone saturated and greedy, the teacher along with the rest). He’s right, too – as well as appealingly modest – in thinking that the best teaching is “of value” straightforwardly, as writing itself somehow can’t be. You don’t get up from your writing table believing you’ve done something “of value to the world”.

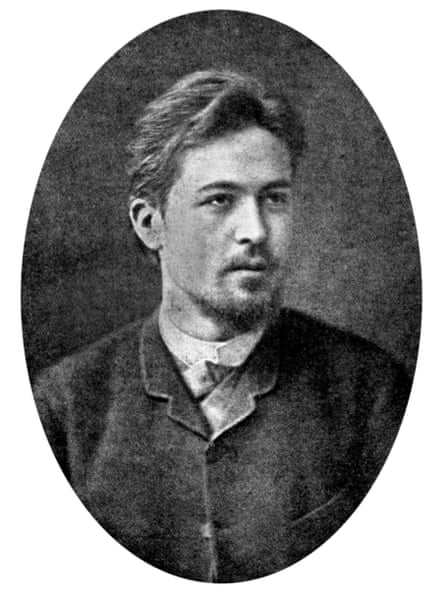

Now Saunders has developed as essays some of the thoughts arising from those classes, and put them together into a book alongside the stories he’s discussing – by Chekhov, Tolstoy, Turgenev and Gogol. These essays aren’t anything like academic analysis. The questions that get asked in a reading-for-writers class are inflected differently from literary criticism – “Why did the writer do this?” rather than “How must we read this?” – even if they converge finally on the same points of appreciation, and the same questions of meaning.

Saunders doesn’t come from the end of a completed story but dives in at the beginning and into the middle, trying to experience it in the making, imagine why it unfolded the way it did. He takes Chekhov’s “In the Cart”, for instance, literally one page at a time, interrupting the text with his interrogations. Now, what do you know? And now? And what are you curious about? Where do you think the story is headed? Why did Chekhov go that way, and not this? So much for the death of the author. This kind of reading (one of the best kinds, I’m convinced) tracks the author’s intentions – and missed intentions, and intuitions, and instinctive recoil from what’s banal or obvious – so closely and intimately, at every step, through every sentence.

Marya, a thwarted, lonely schoolmistress is making her way home in a cart from the town where she’s gone to pick up her salary, to the bleak village school where she works. “She felt as though she had been living in these parts for a long, long time, for a hundred years, and it seemed to her that she knew every stone, every tree on the road from the town to her school. Here was her past and her present, and she could imagine no other future than the school, the road to the town and back … ” Saunders begins to speculate forwards, as any reader is bound to. “The story has said of her, ‘She is unhappy and can’t imagine any other life for herself.’ And we feel the story preparing itself to say something like, ‘Well, we’ll see about that.’”

A less good writer than Chekhov might have worked with the grain of the expectation raised: something might happen to save Marya from her future. A love affair? As if on cue, one attractive and wealthy landowner appears alongside her in his carriage. But nothing doing: the landowner’s a bit useless and ineffective, and anyway Marya’s preoccupied by her problems with the janitor at school, who is rude to her and hits the boys. Good writing works in intricate relationship with a reader’s expectations, raising them and leading them on, then sidestepping or surpassing them. Not merely disappointing them: the story can’t do nothing with Marya, that would be cheating. We’d ask, what was it for, then? The writer has to find a sweet spot between an implausibly happy resolution and a brute refusal of satisfaction. He has to find out what movement there is, and what freedom, inside the story’s particular conditions – but without cheaply magicking them away. Being Chekhov, in this case he finds it. (Read the story.)

All this makes Saunders’s book very different from just another “how to” creative writing manual, or just another critical essay. In enjoyably throwaway fashion, he assembles along his way a few rules for writing. “Be specific! Honour efficiency! … “Always be escalating,” he says. “That’s all a story is, really: a continual system of escalation. A swath of prose earns its place in the story to the extent that it contributes to our sense that the story is (still) escalating.” There’s truth in all of this, though I do wonder whether you can actually learn to write better by following these explicit prescriptions, or rules of craft, extracted from what you read. Perhaps.

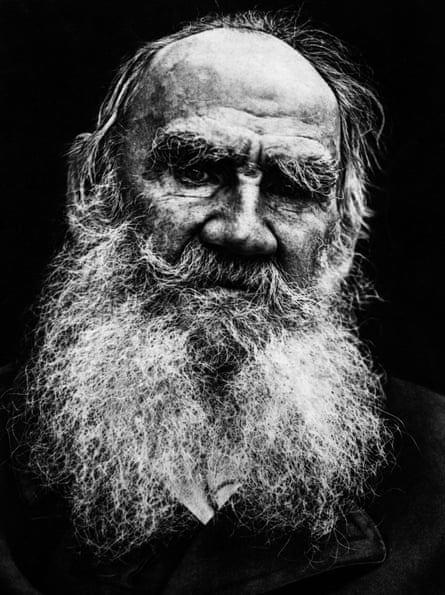

It’s certainly true, in any case, that reading “In the Cart” or Tolstoy’s “Master and Man” with this rich, close attention will mulch down into any would-be writer’s experience, and repay them by fertilising their own work eventually, as they struggle with the words on their own page. Perhaps it’s less like applying a series of lessons and more like the training of an intuition that flashes between hand, eye, mind. That defining human transaction, teaching and learning through imitation, the master’s hand closed over the apprentice’s to guide it.

Saunders’s concentration is often on the forward dynamic of the stories, their “tight, escalatory pattern”. In “a highly organised system, the causation is more pronounced and intentional”. Good writing is “the cumulative result of all this repetitive choosing on the line level, those thousands of editing microdecisions”. This focus on process can sound occasionally like a reductive functionalism – each detail is there because it makes the story work. In reading, though, don’t we feel it the other way round: as if the story were only there so that for a moment we can contemplate the truth of the detail, of the experience?

At the climax of “Master and Man”, wealthy merchant Vasili Andreevich, lost in a snowstorm at night and imagining the reality of his death for the first time, sees tall stalks of wormwood sticking out of the snow, “desperately tossing about under the pressure of the wind which beat it all to one side and whistled through it”. The writing holds us still through its descriptive truthfulness, its miraculous verisimilitude. And that’s in the writer too: he’s not merely thinking how to entertain us more effectively. His effort at that moment of writing, in the midst of all his “repetitive choosing” (which is what makes the story work), is subordinated to the vision in his mind’s eye, which holds still for him even as he labours to bring it into being.

Saunders knows that too. One of the pleasures of this book is feeling his own thinking move backwards and forwards, between the writer dissecting practice and the reader entering in through the spell of the words, to dwell inside the story. He’s particularly good on the ending of Tolstoy’s “Alyosha the Pot”, burrowing into all the things Tolstoy chooses not to say about the death of its protagonist, and ending, after much discussion of the story’s point and its value, with his own “state of wondering”, every time he reads it.