HARD-CORE QUAKER, QUAKER THEOLOGY, SIGNS OF THE TIMES

WILLIAM PENN & THE FRUITS OF TECHNOLOGICAL SOLITUDE

MAY 22, 2017 CHUCK FAGER 4 COMMENTS

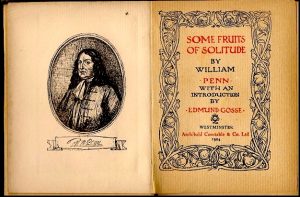

Last First Day I needed a brief reading to open Meeting. Feeling reflective, a little book by William Penn, Some Fruits of Solitude came to mind.

Some Fruits was first published, anonymously, in 1693, and has been in print most of the 320-plus years since. A copy of it has sat on my bookshelf for a few decades.

Some Fruits came to be written because Penn was obliged to disappear for a couple of years. He had to beat it because of his longtime friendship with King James II.

This was an odd friendship, for many reasons: For one, Penn was prominent, yet not part of the nobility; but James had known and liked Penn’s father, an admiral in the Royal Navy. It was also odd because, as a Quaker, Penn was poles apart from James religiously, as the king had become Catholic. Nonetheless, James kept calling Penn in to chat and hang out, while leaving his royal councillors, with lots of actual state business for the monarch to conduct, waiting and fuming.

Penn was not there just to schmooze. He had an agenda, namely nudging James toward issuing a royal declaration of religious toleration, one broad enough to end all persecution of both Quakers and Catholics, both of which were opposed by the Anglican establishment.

Penn felt he was making progress with James; but then in June 1688 his Queen, Mary of Modena, had a son, also named James, who became his heir, the Prince of Wales, destined to become a legitimate Catholic king of England.

This prospect horrified the Anglican church and most of the British establishment, which had been increasingly Protestant since Henry VIII’s reign 150 years earlier. They decided that the new Catholic prince could not be allowed to succeed. So they hatched a plot.

James also had a daughter Mary, who had been raised Protestant and lived in Holland with her Protestant Dutch husband, William of Orange. British plotters soon came to call and invited them to become joint British monarchs in place of her father.

To cut to the chase, William and Mary accepted. Then James, his Queen and the infant prince were tossed out in an essentially bloodless coup, known to British historians as the Glorious Revolution.

James first went more or less quietly into exile; but soon decided to raise an army and try to retake the crown. He failed, but the fighting put everyone who had been Friendly to James under suspicion of joining plots against William and Mary.

And “everyone” included William Penn, never mind his Quaker protestations of nonviolence. For awhile he stood up for himself and his reputation, even braving a couple of stints locked up in the Tower of London. Finally, though, he decided it was more prudent to slip away into the country, far from London. He stayed out of sight until the wave of suspicion receded, and he was ultimately cleared of any treasonous schemes.

In the meantime, far from the madding crowd, the bustle of the city and the hazardous whirl of its politics, Penn had time to think, and write. He had published many essays and books, most of which connected his Quaker convert’s religious fervor to heated issues of the day. But now, out of the swim, he reflected on more general matters of life.

It is from this time of retreat and reappraisal that his thoughts were refined and compressed into a collection of maxims and advices, that became Some Fruits of Solitude.

I didn’t turn to it because of the turbulent history surrounding its composition, though the contours of it were familiar enough; rather I hoped to find and be able to share a glimpse of this broader, deeper perspective, refracted through three centuries, beyond the tumults of the present.

And so I did. Its Preface struck just the right note for me, and I decided its opening paragraphs would serve for a reading. And if it proved useful to Friends, I also hoped to find a version of it, online, and likely available there for free.

The Harvard Classics colophon

The Harvard Classics colophonAnd sure enough, I found one, in rather distinguished company, part of a set, “The Harvard Classics,” issued a century ago. These are described as a “five foot shelf” of the cream of fiction and nonfiction, as selected by the male mandarins of New England. And Penn was not just on the list with such worthies as Plutarch and Homer, but at the head of their number, in the first of its volumes.

My research complete, I read over the passage from the Preface again online, as a hedge against typos and other errors.

It was grammatically correct; but reading the digital Harvard version was a totally different and jarring experience than seeing it on the printed page. So much so, it seemed to me the disjuncture ought to be shared.

So to open worship, I read the brief passage twice: first, as it was presented in the book. Next, as it appeared online.

I’d like to do that here, only visually. You’ll see the difference shortly. So let’s hear from William Penn, in seclusion:

Some Fruits of Solitude, from the printed Preface:

READER—This Enchiridion [or collection] I present thee with, is the Fruit of Solitude: A School few care to learn in, tho’ None instructs us better. Some Parts of it are the Result of serious Reflection: Others the Flashings of Lucid Intervals: Writ for private Satisfaction, and now publish’d for an Help to Human Conduct.

The Author blesseth God for his Retirement, and kisses that Gentle Hand which led him into it: For though it should prove Barren to the World, it can never do so to him.

He has now had some Time he could call his own; a Property he was never so much Master of before: In which he has taken a View of himself and the World; and observed wherein he hath hit and mist the Mark; What might have been done, what mended, and what avoided in his Human Conduct: Together with the Omissions and Excesses of others, as well Societies and Governments, as private Families, and Persons.

And he verily thinks, were he to live over his Life again, he could not only, with God’s Grace, serve Him, but his Neighbor and himself, better than he hath done, and have Seven Years of his Time to spare. And yet perhaps he hath not been the Worst or the Idlest Man in the World; nor is he the Oldest. And this is the rather said, that it might quicken, Thee, Reader, to lose none of the Time that is yet thine.

There is nothing of which we are apt to be so lavish as of Time, and about which we ought to be more solicitous; since without it we can do nothing in this World. Time is what we want most, but what, alas! we use worst; and for which God will certainly most strictly reckon with us, when Time shall be no more. . . .

Now, the ONLINE version:

READER—This Enchiridion [or collection] I present thee with, is the Fruit of Solitude: A School few care to learn in, tho’ None instructs us better.

Some Parts of it are the Result of serious Reflection: Others the Flashings of Lucid Intervals: Writ for private Satisfaction, and now publish’d for an Help to Human Conduct.

The Author blesseth God for his Retirement, and kisses that Gentle Hand which led him into it: For though it should prove Barren to the World, it can never do so to him.

He has now had some Time he could call his own; a Property he was never so much Master of before: In which he has taken a View of himself and the World;

and observed wherein he hath hit and mist the Mark; What might have been done, what mended, and what avoided in his Human Conduct:

Together with the Omissions and Excesses of others, as well Societies and Governments, as private Families, and Persons.

And he verily thinks, were he to live over his Life again, he could not only, with God’s Grace, serve Him, but his Neighbor and himself, better than he hath done, and have Seven Years of his Time to spare.

And yet perhaps he hath not been the Worst or the Idlest Man in the World; nor is he the Oldest.

And this is the rather said, that it might quicken, Thee, Reader, to lose none of the Time that is yet thine.

There is nothing of which we are apt to be so lavish as of Time, and about which we ought to be more solicitous; since without it we can do nothing in this World.

Time is what we want most, but what, alas! we use worst; and for which God will certainly most strictly reckon with us, when Time shall be no more . . . .

So, you get the idea. All these popup ads appeared on the page I was looking at, one after another. I guess one could say that, the FRUITS are still there, I think. But the Solitude is definitely gone.

Fortunately for readers seeking the fruits online, there are other versions of this text, into which the popups have not (yet) seeped. Which was a relief. I’m hopeful there will be such an alternative to be found for the volume right next to Penn in the venerable Harvard “canon,” which I could not bear to look at.

Yes, it’s the Journal of John Woolman (with doubtless no extra charge for the free credit report, and plenty of big little lies, and maybe even another toilet lawsuit . . . .