Lou Andreas-Salomé

Lou Andreas-Salomé | |

|---|---|

Lou Andreas-Salomé in 1897 | |

| Born | 12 February 1861 |

| Died | 5 February 1937 (aged 75) Göttingen, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

Lou Andreas-Salomé (born either Louise von Salomé or Luíza Gustavovna Salomé or Lioulia von Salomé, Russian: Луиза Густавовна Саломе; 12 February 1861 – 5 February 1937) was a Russian-born psychoanalyst and a well-traveled author, narrator, and essayist from a French Huguenot-German family.[1] Her diverse intellectual interests led to friendships with a broad array of distinguished thinkers, including Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Paul Rée, and Rainer Maria Rilke.[2]

Life[edit]

Early years[edit]

Lou Salomé was born in St. Petersburg to Gustav Ludwig von Salomé (1807–1878), and Louise von Salomé (née Wilm) (1823–1913). Lou was their only daughter; they had five sons. Although she would later be attacked by the Nazis as a "Finnish Jew",[3] her parents were actually of French Huguenot and Northern German descent.[4] The youngest of six children, she grew up in a wealthy and well-cultured household, with all children learning Russian, German, and French; Salomé was allowed to attend her brothers' classes.

Born into a strictly Protestant family, Salomé grew to resent the Reformed church and Hermann Dalton, the Orthodox Protestant pastor. She refused to be confirmed by Dalton, officially left the church at age 16, but remained interested in intellectual pursuits in the areas of philosophy, literature and religion.

In fact, she was fascinated by the sermons of the Dutch pastor Hendrik Gillot, known in St. Petersburg as an opponent of Dalton's. Gillot, 25 years her senior, took her on as a student, engaging with her in the fields of theology, philosophy, world religions, and French and German literature. Together they studied innumerable authors, philosophers, theological and religious subjects, and all of this wide-ranging study laid the groundwork for her intellectual encounters with very well-known thinkers of her time. Gillot became so smitten with Salomé that he wanted to divorce his wife and marry his young student. Salomé refused, for she was not interested in marriage and sexual relations. Though disappointed and shocked by this development, she remained friends with Gillot.

Following her father's death in 1879, Salomé and her mother went to Zürich so Salomé could acquire a university education as a "guest student." In her one year at the University of Zurich—one of the few schools that accepted female students—Salomé attended lectures in philosophy (logic, history of philosophy, ancient philosophy, and psychology) and theology (dogmatics). During this time, Salomé's physical health was failing due to lung disease, causing her to cough up blood. Due to this, she was instructed to heal in warmer climates, so in February 1882, Salomé and her mother went to Rome.

Rée and Nietzsche, and later life[edit]

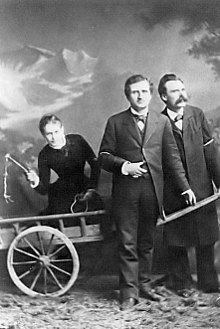

Salomé's mother took her to Rome when Salomé was 21. At a literary salon in the city, Salomé became acquainted with the author Paul Rée. Rée proposed to her, but she instead suggested that they live and study together as 'brother and sister' along with another man for company, and thereby establish an academic commune.[5] Rée accepted the idea, and suggested that they be joined by his friend Friedrich Nietzsche. The two met Nietzsche in Rome in April 1882, and Nietzsche is believed to have instantly fallen in love with Salomé, as Rée had earlier done. Nietzsche asked Rée to propose marriage to Salomé on his behalf, which she rejected. She had been interested in Nietzsche as a friend, but not as a husband.[5] Nietzsche nonetheless was content to join Rée and Salomé touring through Switzerland and Italy together, planning their commune. On 13 May, in Lucerne, when Nietzsche was alone with Salomé, he earnestly proposed marriage to her again, and she again rejected him. He was happy to continue with the plans for an academic commune.[5] After discovering the situation, Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth became determined to get Nietzsche away from what she described as the "immoral woman".[6] The three travelled with Salomé's mother through Italy and considered where they would set up their "Winterplan" commune. This commune was intended to be set up in an abandoned monastery, but as no suitable location was found, the plan was abandoned.

After arriving in Leipzig in October 1882, the three spent a number of weeks together. However, the following month Rée and Salomé parted company with Nietzsche, leaving for Stibbe without any plans to meet again. Nietzsche soon fell into a period of mental anguish, although he continued to write to Rée, asking him, "We shall see one another from time to time, won't we?"[7] In later recriminations, Nietzsche would blame the failure in his attempts to woo Salomé both on Salomé, Rée, and on the intrigues of his sister (who had written letters to the families of Salomé and Rée to disrupt their plans for the commune). Nietzsche wrote of the affair in 1883 that he felt "genuine hatred for [his] sister".[7]

Salomé would later (1894) write a study, Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken (Friedrich Nietzsche in his Works), of Nietzsche's personality and philosophy.[8]

In 1884 Salomé became acquainted with Helene von Druskowitz, the second woman to receive a philosophy doctorate in Zurich.[citation needed] It was also rumoured that Salomé later had a romantic relationship with Sigmund Freud.[9]

Marriage and relationships[edit]

Salomé and Rée moved to Berlin and lived together until a few years before her celibate marriage[10] to linguistics scholar Friedrich Carl Andreas. Despite her opposition to marriage and her open relationships with other men, Salomé and Andreas remained married from 1887 until his death in 1930.

Salomé's co-habitation with Andreas caused the despairing Rée to fade from Salomé's life despite her assurances. Throughout her married life, she engaged in affairs and/or correspondence with the German journalist and politician Georg Ledebour, the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, about whom she wrote an analytical memoir,[11] and the psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Victor Tausk, among others. Accounts of many of these are given in her volume Lebensrückblick. Her relationship with Freud was still quite intellectual despite gossip about their romantic involvement. In one letter Freud commends Salomé's deep understanding of people so much that he believed she understood people better than they understood themselves. The two often exchanged letters.[12]

Meeting Rilke[edit]

In May 1897, in Munich, she met Rilke, who had been introduced to her by Jacob Wassermann.[13] She was 37 while Rilke was only 21. She had already published with some success Im Kampf um Gott "where she exposed the problem of loss of faith (which had been her own for a long time)", several articles, and the study Jesus der Jude that Rilke had read.[13]

As Philippe Jaccottet reports, Salomé wrote in Lebensrückblick: "I was your wife for years because you were the first reality, where man and body are indistinguishable from each other, an indisputable fact of life itself. I could have said literally what you told me when you confessed your love to me: Only you are real. That is how we became husband and wife even before we became friends, not by choice, but by this unfathomable marriage [...] We were brother and sister, but as in a distant past, before the marriage between brother and sister became sacrilegious".[14]

In 1899 with her husband Friedrich-Carl, then again in 1900, Lou travelled to Russia, the second time with Rilke, whose first name she changed from René to Rainer.[15] She taught him Russian, to read Tolstoy (whom he would later meet) and Pushkin. She introduced him to patrons and other people in the arts, remaining Rilke's advisor, confidante, and muse throughout his adult life.[10] The romance between the poet and Lou lasted three years, then turned into a friendship, which would continue until Rilke's death, as evidenced by their correspondence. In 1937, Freud said of Salomé's relationship with Rilke: "she was both the muse and the attentive mother of the great poet".[16]

Death[edit]

By 1930, Salomé was increasingly weak, suffered from a heart condition and diabetes, and had to be treated several times in the hospital. Her husband visited her daily during a six-week stay after a foot operation, which was arduous for the old, rather ill man, and this made them grow very close after a forty-year marriage marked by hurtful behaviour on both sides and long periods of non-communication.[17] Freud appreciated this from afar, writing: "only what is true proves itself so long-lasting" ("So dauerhaft beweist sich doch nur das Echte."). Friedrich Carl Andreas died of cancer in 1930, and Salomé herself underwent a difficult cancer operation in 1935. At the age of 74, she ceased to work as a psychoanalyst.

On the evening of 5 February 1937, Salomé died in her sleep due to uremia in Göttingen. Her urn was laid to rest in her husband's grave in the cemetery on the Groner Landstraße in Göttingen. She is commemorated in the city by a memorial plaque outside the property where her house stood, a street named after her (Lou-Andreas-Salomé-Weg), and the name of the Lou Andreas-Salomé Institut für Psychoanalyse und Psychotherapie. A few days before her death, the Gestapo confiscated her library (according to other sources it was an SA group who destroyed the library shortly after her death). The reasons given for this confiscation were that she had been a colleague of Sigmund Freud's, had practised "a Jewish science", and owned many books by Jewish authors.[18]

Work[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

Salomé was a prolific writer who wrote fiction, criticism and essays on religion, philosophy, sexuality and psychology.[19] A uniform edition of her works is being published in Germany by MedienEdition Welsch.[20] She authored a "Hymn to Life" that so deeply impressed Nietzsche that he was moved to set it to music. Salomé's literary and analytical studies became such a vogue in Göttingen, where she lived late in her life, that the Gestapo waited until shortly after her death to "clean" her library of works by Jews.

She was one of the first female psychoanalysts and one of the first women to write psychoanalytically on female sexuality,[21] before Helene Deutsch, for instance in her essay on the anal-erotic (1916),[22] an essay admired by Freud.[23] However, she had written about the psychology of female sexuality before she ever met Freud, in her book Die Erotik (1911).

She wrote more than a dozen novels and novellas, including Im Kampf um Gott, Ruth, Rodinka, Ma, Fenitschka – eine Ausschweifung, as well as non-fiction studies such as Henrik Ibsens Frauengestalten (1892), a study of Ibsen's female characters, and a book on Nietzsche, Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken (1894). The first English translation of her novel Das Haus (1921) appeared in 2021 under the title Anneliese's House, in an annotated edition by Frank Beck and Raleigh Whitinger.[24]

Salomé edited a memoir about Rilke after his death in 1926. Among her works is also her Lebensrückblick, which she wrote during her last years based on memories of her life as a free woman. In her memoirs, first published in their original German in 1951, she goes into depth about her faith and her relationships.

Salomé is said to have remarked in her last days, "I have really done nothing but work all my life, work ... why?" And in her last hours, as if talking to herself, she is reported to have said, "If I let my thoughts roam I find no one. The best, after all, is death."[26]

Published works[edit]

Lou Andreas-Salomé's published works as cited by An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers.[27]: 36–38

- Im Kampf um Gott, 1885.

- Henrik Ibsens Frau-Gestalten, 1892.

- Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, 1894.

- Ruth, 1895, 1897.

- Fenitshcka. Eine Ausschweifung, 1898,1983.

- Menschenkinder, 1899.

- Aus fremder Seele, 1901.

- Ma, 1901.

- Im Zwischenland, 1902.

- Die Erotik, 1910.

- Drei Briefe an einen Knaben, 1917.

- Das Haus, 1919,1927.

- Die Stunde ohne Gott und andere Kindergeschichten, 1921.

- Der Teufel und seine Grossmutter, 1922.

- Rodinka, 1923.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, 1928.

- Mein Dank an Freud: Offener Brief an Professor Freud zu seinem 75 Geburtstag, 1931.

- Lebensrückblick. Grundriss einiger Lebenserinnerungen, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1951, 1968.

- Rainer Maria Rilke – Lou Andreas-Salomé. Briefwechsel, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1952.

- In der Schule bei Freud, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1958.

- Sigmund Freud – Lou Andreas-Salomé. Briefwechsel, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1966.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Paul Rée, Lou von Salomé: Die Dokumente ihrer Begegnung, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1970.

Translations:

- The Freud Journal of Lou Andreas-Salomé, tr. Stanley Leavy, 1964.

- Sigmund Freud and Lou Andreas-Salomé, Letters, tr. byu W. and E. Robson Scott, 1972.

- Ibsen's Heroines, ed., tr., and introd. by Siegfried Mandel, 1985.

- Anneliese's House, edited and translated by Frank Beck and Raleigh Whitinger. Boydell and Brewer, 2021.

In fiction and film[edit]

Fictional accounts of Salomé's relationship with Nietzsche occur in four novels: Irvin Yalom's When Nietzsche Wept,[28] Lance Olsen's Nietzsche's Kisses, Beatriz Rivas', La hora sin diosas (The time without goddesses).[29] and William Bayer's The Luzern Photograph, in which two reenactments of the famous image of her with Nietzsche and Rée impact a murder in contemporary Oakland, California.[30]

Mexican playwright Sabina Berman includes Lou Andreas-Salomé as a character in her 2000 play Feliz nuevo siglo, Doktor Freud (Freud Skating).[31]

Salomé is also fictionalized in Angela von der Lippe's The Truth about Lou,[32] in Brenda Webster's Vienna Triangle,[33] in Clare Morgan's A Book for All and None,[34] in Robert Langs' two-act play Freud's Bird of Prey,[35] and in Araceli Bruch's five-act play Re-Call (written in Catalan).[36]

In Liliana Cavani's movie Al di la' del bene e del male (Beyond Good and Evil) Salome is played by Dominique Sanda. In Pinchas Perry's film version of When Nietzsche Wept, Salome is played by Katheryn Winnick.

Lou Salome, an opera in two acts by Giuseppe Sinopoli with libretto from Karl Dietrich Gräwe, premiered 1981 at the Bavarian State Opera, with August Everding as General Director, staging by Götz Friedrich and set design by Andreas Reinhardt.[37]

Lou Andreas-Salomé, The Audacity to be Free, a German-language movie directed by Cordula Kablitz-Post, released in German cinemas on 30 June 2016.[38] Andreas-Salome is portrayed onscreen by Katharina Lorenz and as a young woman by Liv Lisa Fries. The film was released in New York City and Los Angeles in April 2018, with a wider release to follow.

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Lou Andreas-Salome biography". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Lou Andreas-Salome | German writer". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Young, Julian. Friedrich Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography. Cambridge University Press (2010) p. 553. ISBN 9780521871174

- ^ Powell, Anthony (1994). Under Review: Further Writings on Writers, 1946–1990. University of Chicago Press. p. 440. ISBN 0-226-67712-5.

- ^ a b c Nietzsche: The Man and his Philosophy, by R.J. Hollingdale (Cambridge University Press 1999), page 149

- ^ Nietzsche: The Man and his Philosophy, by R.J. Hollingdale (Cambridge University Press 1999), page 151

- ^ a b Nietzsche: The Man and his Philosophy, by R.J. Hollingdale (Cambridge University Press 1999), page 152

- ^ Salomé, 2001

- ^ Borossa, Julia; Rooney, Caroline. "Suffering, Transience and Immortal Longings Salomé Between Neitzsche and Freud". The Gale Group. Sage Publications. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ a b Mark M. Anderson, "The Poet and the Muse", The Nation, 3 July 2006, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Andreas-Salomé, 2003

- ^ Borossa, Julia; Rooney, Caroline. "Suffering, Transience and Immortal Longings Salome Between Nietzsche and Freud". The Gale Group. Sage Publications. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ a b Philippe Jaccottet, Rilke par lui-même, 1970, p.29

- ^ Philippe Jaccottet, Rilke par lui-même, 1970, p.29–30

- ^ Gerald Stieg, 2007, p.979-980

- ^ Roudinesco and Plon, 2011, p. 65

- ^ "Lou Andreas-Salomé © 2003-2012 by Prof. Dr. med. K. Sadegh-Zadeh". www.lou-andreas-salome.de. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Heinz F. Peters: Lou Andreas-Salomé: Das Leben einer außergewöhnlichen Frau. Kindler, München 1964, S. 7 (Vorwort, ohne Quellenangabe).

- ^ Livingstone, Angela (1984). Salomé: Her Life and Work. London: Gordon Fraser Gallery. pp. 246–248.

- ^ "Lou Andreas-Salomé Werkedition". andreas-salome.medienedition.de. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Popova, Maria (12 February 2015). "Lou Andreas-Salomé, the First Woman Psychoanalyst, on Human Nature in Letters to Freud". Brain Pickings. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Andreas-Salome, Lou (April 2022). ""Anal" and "Sexual"". Psychoanalysis and History. 24 (1): 19–40. doi:10.3366/pah.2022.040. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund. Richards, Angela, editor. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality and Other Works. The Penguin Freud Library, Vol. 7 Penguin. (1977) ISBN 9780140137972 pp.295-302

- ^ "Anneliese's House". Boydell and Brewer. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Books of The Times – Her Friends Included Nietzsche, Rilke and Freud". The New York Times. 10 May 1991.

- ^ Peters, 'My Sister, My Spouse', p. 300

- ^ Wilson, Katharina M. (1991). An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc.

- ^ "When Nietzsche Wept". Litmed.med.nyu.edu. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ "La hora sin diosas". Alfaguara.com. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Bayer, William, The Luzern Photograph; ISBN 978-0-7278-8546-3

- ^ Bruno Bosteels (21 August 2012). Marx and Freud in Latin America: Politics, Psychoanalysis, and Religion in ... p. 237. ISBN 9781844678471. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ The Truth about Lou; ISBN 1-58243-358-5

- ^ Vienna Triangle; ISBN 978-0-916727-50-5

- ^ A Book for All and None; ISBN 978-0-7538-2892-2

- ^ Freud's Bird of Prey; ISBN 1-891944-03-7

- ^ Re-Call; ISBN 1905512201

- ^ "Lou Salome: Muse, Geliebte, Therapeutin". Musik in Dresden. 6 February 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ "In Love with Lou". World Literature Today. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

References[edit]

- Astor, Dorian: Lou Andreas-Salomé, Gallimard, folio biographies, 2008; ISBN 978-2-07-033918-1

- Binion, R., Frau Lou: Nietzsche's Wayward Disciple, foreword by Walter Kaufmann, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1968

- Freud, S. and Lou Andreas-Salome: Letters, New York: Norton, 1985

- Jaccottet, Philippe, Rilke par lui-même, Paris, Seuil, coll. " Ecrivains de toujours ", 1970, " Naissance de Rainer-Maria ", p. 29–37

- Livingstone, Angela: (1984). Lou Andreas Salomé: Her Life and Work. London: Gordon Fraser, 1984; ISBN 0918825040

- Michaud, Stéphane: Lou Andreas-Salomé. L'alliée de la vie. Seuil, Paris 2000; ISBN 2-02-023087-9

- Pechota Vuilleumier, Cornelia: 'O Vater, laß uns ziehn!' Literarische Vater-Töchter um 1900. Gabriele Reuter, Hedwig Dohm, Lou Andreas- Salomé. Olms, Hildesheim 2005; ISBN 3-487-12873-X

- Pechota Vuilleumier, Cornelia: Heim und Unheimlichkeit bei Rainer Maria Rilke und Lou Andreas-Salomé. Literarische Wechselwirkungen. Olms, Hildesheim 2010; ISBN 978-3-487-14252-4

- Peters, H. F., My Sister, My Spouse: A Biography of Lou Andreas-Salome, New York: Norton, 1962

- Roudinesco, Elisabeth et Michel Plon, Dictionnaire de la psychanalyse, Paris, Fayard, coll. " La Pochothèque ", 2011 (1re éd. 1997) (ISBN 978-2-253-08854-7), " Andreas-Salomé Lou, née Liola (Louise) von Salomé (1861–1937). Femme de lettres et psychanalyste allemande ", p. 63–68

- Salomé, Lou: The Freud Journal, Texas Bookman, 1996

- Salomé, Lou: Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, 1894; Eng., Nietzsche, tr. and ed. Siegfried Mandel, Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press Univ. of Illinois Press, 2001

- Salomé, Lou: You Alone Are Real to Me: Remembering Rainer Maria Rilke, tr. Angela von der Lippe, Rochester: BOA Editions, 2003

- Stieg, Gerald: « Rilke (Rainer Maria) », in Dictionnaire du monde germanique , Dir: É. Décultot, M. Espagne et J. Le Rider, Paris, Bayard, 2007, p. 979–980 (ISBN 9782227476523)

- Vollmann, William T., Friedrich Nietzsche: The Constructive Nihilist, The New York Times, 14 August 2005.

- Vickers, Julia: Lou von Salome: A Biography of the Woman who Inspired Freud, Nietzsche and Rilke. McFarland 2008

External links[edit]

- Works by Lou Andreas-Salomé at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Lou Andreas-Salomé at Internet Archive

- Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, Wien, Verlag von Carl Konegen, 1894.

- Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, Wien, Verlagsbuchhandlung Carl Konegen, 1911.

- Articles on Lou Andreas-Salomé in the Encyclopedia of World Biography, the Encyclopedia of Modern Europe, and the International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis

- Lou Andreas-Salomé by Paul B. Goodwin in Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia

- Lou Andreas-Salomé by Petri Liukkonen