Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered: Devall, Bill, Sessions, George: 9780879052478: Amazon.com: Books

Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered Paperback – January 19, 2001

by Bill Devall (Author), George Sessions (Contributor)

4.1 out of 5 stars 13 ratings

-------------------

Practicing is simple. Nothing forced, nothing violent, just settling into our place. "Deep ecology," a term originated in 1972 by Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess, is emerging as a way to develop harmony between individuals, communities and nature. DEEP ECOLOGY--the term and the book--unfolds the path to living a simple, rich life and shows how to participate in major environmental issues in a positive and creative manner.

------------

Contents

Preface Nothing Can Be Done, Everything is Possible Minority Tradition and Direct Action The Dominant, Modern Worldview and Its Critics The Reformist Response Deep Ecology Some Sources of the Deep Ecology Perspective Why Wilderness in the Nuclear Age? Nature Resource Conservation or Protection of the Integrity of Nature: Contrasting Views of Management Ecotopia: The Vision Defined

From the Back Cover

Deep Ecology explores the philosophical, psychological, and sociological roots of today's environmental movement, examines the human-centered assumptions behind most approaches to nature, explores the possibilities of an expanded human consciousness, and offers specific direct action suggestions for individuals to practice. Widely read in it first printing, Deep Ecology has established itself as one of the most significant books on environmental thought to appear in this decade.

"Deep Ecology is subversive, but it's the kind of subversion we can use." --San Francisco Chronicle

"This book is an attempt at codifying a scattered body of ecological insight into a philosophy that places human beings on an absolutely equal footing with all other creatures on the planet." --Stephanie Mills, Whole Earth Review

"Difficult and (to some) unfamiliar insights on nature and human beings presented with simplicity and clarity, Deep Ecology rattles a cage full of occidental presumptions and yet it all seems almost like common sense." --Gary Snyder

Bill Devall has studied the social organization, politics, psychology and philosophy of the environmental movement for fifteen years. He teaches at Humbolt State University in California and is active in many environmental groups including Earth First! and the Sierra Club.

George Sessions teaches philosophy at Sierra College California. He was appointed to the Mountaineering Committee of the the Sierra Club in 1962, has served as a philosophy consultant to the National Endowment for the Humanities, and is editor of the International Ecophilosophy Newsletter.

About the Author

Bill DeVall has been a guest lecturer and featured speaker at universities in the United States and Australia and at national and international environmental conferences.

---

In this first chapter we assume that the environmental/ecology movement has been a response to the awareness by many people that something is drastically wrong, out of balance in our contemporary culture. In the first section, we present several alternative scenarios for the movement. These scenarios will provide a context in which to understand deep ecology. Some of the major themes of deep ecology and of cultivating ecological consciousness are discussed in the second section of the chapter.

----

Read less

Product details

Paperback: 280 pages

Publisher: Gibbs Smith Publisher (January 19, 2001)

---

Bill Devall

4.1 out of 5 stars

4.1 out of 5

---

Top Reviews

James Storm Shirley

5.0 out of 5 stars Great thinking book...

Reviewed in the United States on December 12, 2012

Verified Purchase

As advertised, long sought out, slow, going read.... but worth it, and should be read by anyone thinking about doing more for the planet

2 people found this helpful

Helpful

Comment Report abuse

cisco

2.0 out of 5 stars Heavy

Reviewed in the United States on February 4, 2016

Verified Purchase

Way to deep and dated for me.

2 people found this helpful

Helpful

Comment Report abuse

Greg Bassham

3.0 out of 5 stars A Blast from the Hippy Dippy Past

Reviewed in the United States on January 17, 2019

This book is a quirky classic, a veritable cornucopia of 60s countercultural buzz words, utopianism, and mystical mush. Drawing on an eclectic range of sources (Thoreau, Muir, Naess, Eastern spirituality, Native American earth wisdom, anarchist social ecology, Gandhian nonviolence, 60s environmental radicalism, etc.), Devall and Sessions argue against human-centered "reformist" environmentalism and for a radical deep ecology that calls for profound and far-reaching changes in how humans live and relate to nature. It is anti-capitalism, anti-technology, anti-urban, anti-big-government, and anti-anthropocentrism. Deep ecology, in their view, is based on two major value commitments: (1) self-realization and (2) biocentric egalitarianism. Following Naess, by self-realization they don't mean pursuit of egoistic gratifications, but identification with the Whole of nature/reality and a commitment to the blossoming of all forms of life. By biocentric egalitarianism they mean a recognition that all living things (and even some nonliving ecological wholes such as rivers, mountains, etc.) have equal intrinsic value and deserve equal moral respect and consideration. Oddly, neither of these two central normative principles are included in the famous eight-point "Platform" of basic principles of deep ecology (p. 70) they endorse. In practical terms, the vision of deep ecology they favor involves a drastic reduction in human population, a rewilding of much of the globe, a rejection of "the dominant worldview" and modern technocratic-industrial civilization, and a return to what they call "the minority tradition" of small, self-regulating communities living in close harmony with nature, much as primal peoples once lived.

If this sounds like crackpot, pastoral utopianism, it is. Not a shadow of practicality or realism ever darkens their sunshiny dream of a re-greened Earth sprinkled with a few happy "mixed communities of humans, rivers, deer, wolves, insects and trees" (p. 205). It's Thoreau on acid. Charming in its way, but badly dated and wholly impractical.

Read more

3 people found this helpful

Helpful

Comment Report abuse

Howzat

5.0 out of 5 stars This 16-page article nicely summarizes Catton's 1980 book

Reviewed in the United States on April 25, 2018

For me, this book is well worth buying for one article: On The Dire Destiny of Human Lemmings by William Cotton, Jr. This 16-page article nicely summarizes Catton's 1980 book, Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change. Both writings are about carrying capacity, i.e., the maximum population of a given species which a particular habitat can support indefinitely (under specified technology and organization, in the case of human species). Catton uses the simple example of how lemmings predictably and periodically overshoot the carrying capacity of their simple habitat. Though the principles of carrying capacity are easy to observe and understand for the lemming, those same principles apply to much more complicated habitats, including the whole earth. The principles apply to all species, including humans. Hence, the title of Catton's article in the book, Deep Ecology.

Cotton explains the Take Over method of increasing the earth's carrying capacity for humans, the method of using technological advances (fire, stone tools, etc.) to gradually expand their population and territories, though this has been at the expense of other species. The Take Over method, however, is generally sustainable.

This is contrasted with the Draw Down method in which humans draw down finite supplies of natural resources at a rate which is faster than the resources can be replenished. Thus, expanding earth's carrying capicity for humans using draw down is not sustainable, and is seem by the author as stealing from future generations. Furthermore, continued use of draw down to expand human population will lead to a population crash. Catton is not Malthus nor Erlich , and has a much more sophisticated understanding of carrying capacity as it applies to human cultural and population growth. His 2009 book, Bottleneck, expands on Overshoot buy describing various techniques used by humans to sustainably increased population, as well as, describing clever, but unwise methods by which humans attempt to avoid limits of carrying capacity and continue their unsustainable economic and population growth.

You have to read his stuff because it's not easy to explain in a book review. I read a lot of environmental books about the history of different scientific disciplines and the new scientific findings in science. My main concern is climate science. I am continually trying to gain an accurate understanding of how the earth many systems function and how humans function within the host Earth. Catton's work influenced me more than any other single author.

Read less

3 people found this helpful

Helpful

Comment Report abuse

See all reviews from the United States

Top international reviews

fitboy

5.0 out of 5 stars Quick delivery

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on December 29, 2018

Verified Purchase

Arrived in the condition as described. Very good book.

Helpful

Report abuse

roger h stopford

5.0 out of 5 stars Five Stars

Reviewed in Canada on January 16, 2016

Verified Purchase

excellent - exactly as advertised

Helpful

Report abuse

Meditation novice

5.0 out of 5 stars Very satisfied

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on October 6, 2011

Verified Purchase

Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature MatteredAnother great service from Amazon. This book was ordered from America, it was in excellent condition for second hand and an amazingly cheap price and delivered when it was planned.

Helpful

Report abuse

Showing posts with label Thoreau. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Thoreau. Show all posts

2020/06/05

2020/05/26

A Calendar of Wisdom: Tolstoy, Leo, Sekirin

A Calendar of Wisdom: Daily Thoughts to Nourish the Soul, Written and Selected from the World's Sacred Texts: Tolstoy, Leo, Sekirin, Peter: 9780684837932: Amazon.com: Books

Peter Sekirin

A Calendar of Wisdom: Daily Thoughts to Nourish the Soul, Written and Selected from the World's Sacred Texts Hardcover – October 14, 1997

by Leo Tolstoy (Author), Peter Sekirin (Editor)

4.5 out of 5 stars 152 ratings

Editorial Reviews

From Library Journal

Tolstoy's last major work reflects his desire to proselytize the moral faith and ideals he struggled to put into practice in his later years. Tolstoy believed that reading daily from the world's great literature was imperative for both his own spiritual edification and that of his readers, so he set himself the task of gathering a wide range of wisdom for every day of the year. He translated, abbreviated, and in many cases expressed entirely in his own words these "quotations" from diverse sources such as the New Testament, the Koran, Greek philosophy, Lao-Tzu, Buddhist thought, and the poetry, novels, and essays of both ancient writers and contemporary thinkers. An important book now released in English for the first time.

Copyright 1997 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Review

"Sekirin's translation is accurate and graceful." - The Slavic and East European Journal.

"A bedside companion." - USA Today.

"A surprisingly powerful book." - The Washington Post.

"War and peace, and quiet." Harper's Magazine, New York.

"A great gift." -- Russian Life Magazine (Montpelier, Vermont).

"New & Noted An editor's selection." - The Globe and Mail, Toronto, Ont.

"Nourish your soul with calendar offerings" - Detroit Free Press.

"Even if you don't quite get the whole 'Fifty Shades of Grey' thing. Maybe with

Tolstoy's 'Calendar of Wisdom'? " - Boston Globe.

"Drawing on deep thinkers - it lights up the reader's life." - Kingston Whig - Standard.

"More war than peace in a triumphant finale." - The Times, London (UK).

"Fables and wisdom nuggets." - Tolstoy Studies Journal.

"A self-help book." - Minneapolis Star Tribune.

"This book will inspire." - The Sun, London (UK).

"SPIRITUAL SEEKERS FIND VOLUMES FOR THE SOUL." - Seattle Times.

"Nourish your soul with calendars offering daily doses of wisdom." - The Detroit News.

"Gems of inspiration." - Greensboro News Record, Greensboro, N.C.

"Simplicity and wisdom." - The Vancouver Sun.

"Tolstoy's last major work. . . . An important book." - Library Journal.

"Tolstoy by halves." - Publishers Weekly.

From the Publisher

This is the first-ever English-language edition of the book Leo Tolstoy considered to be his most important contribution to humanity, the work of his life's last years. Widely read in prerevolutionary Russia, banned and forgotten under Communism; and recently rediscovered to great excitement, A Calendar of Wisdom is a day-by-day guide that illuminates the path of a life worth living with a brightness undimmed by time. Unjustly censored for nearly a century, it deserves to be placed with the few books in our history that will never cease teaching us the essence of what is important in this world.

From the Back Cover

This is the first-ever English-language edition of the book Leo Tolstoy considered to be his most important contribution to humanity, the work of his life's last years. Widely read in pre-revolutionary Russia, banned and forgotten under Communism, and recently rediscovered to great excitement, A Calendar of Wisdom is a day-by-day guide that illuminates the path of a life worth living with a brightness undimmed by time. Unjustly censored for nearly a century, it deserves to be placed with the few books in our history that will never cease teaching us the essence of what is important in this world.

Read less

Product details

Hardcover: 384 pages

Publisher: Scribner; 37982nd edition (October 14, 1997)

Customer reviews

4.5 out of 5 stars

4.5 out of 5

152 customer ratings

----

Top Reviews

Lawrence L. Willett

2.0 out of 5 stars Tolstoy's original work is wonderful but the Sekirin Translation is not.Reviewed in the United States on August 29, 2017

Verified Purchase

When I first purchased and read this book, one day at a time, since it was meant to be a "daily inspirational" book, I very much enjoyed it, but then I also purchased a Russian Language Edition, Circle of Reading (Круг Чтения), that was printed in 2015 at Moscow.

At this time I noted that there were many entire Daily Sections in the Sekirin Translation that are not in in the Russian Edition. For example, in the Sekirin version, for the August 15 page, the entire entry speaks about the virtue of not eating meat, and when I had earlier read this the first time I was pleased because I am a Vegetarian; however, this vegetarian page is not contained in the 2015 Russian Language Edition.

To further determine which edition, either the Sekirin or the 2015 Moscow Russian Edition was correct, I purchased a copy of the 2-volume, 1923 Russian Language Edition published in Berlin by I. P. Ladizhnikova. The Berlin 1923 Russian Language Edition and the 2015 Moscow Russian Language Edition are identical.

Although, as a Vegetarian I did enjoy the advocacy extolling the benefits of not eating meat, I think Sekirin made an egregious error in replacing the very good messages that Tolstoy placed in his original book for August 15. Sekirin should have simply translated Tolstoy's messages and not replaced Tolstoy's beliefs with his own. I am still reading the Circle of Reading on a daily basis but now am comparing the different editions just to see what other changes may have been made. Sekirin is a great disappointment for me and I will not be purchasing any of his other works.

110 people found this helpful

HelpfulComment Report abuse

Brandon Matuja

5.0 out of 5 stars Tolstoy's last major work.Reviewed in the United States on September 16, 2015

Verified Purchase

I'm so glad to have found this book, a rare book in America, here for the first time in English (recently), apparently. It was one of Tolstoy's very last works (THE last?), and he stated that it was his favorite of his own books. Which was humble of him to say, because it's probably at least half composed of various quotations and sayings of wisdom from a wide array of philosophers, Christian, non-Christian, and even secular. The other half or so of the book is his own thoughts and messages to us.

110 people found this helpful

HelpfulComment Report abuse

Brandon Matuja

5.0 out of 5 stars Tolstoy's last major work.Reviewed in the United States on September 16, 2015

Verified Purchase

I'm so glad to have found this book, a rare book in America, here for the first time in English (recently), apparently. It was one of Tolstoy's very last works (THE last?), and he stated that it was his favorite of his own books. Which was humble of him to say, because it's probably at least half composed of various quotations and sayings of wisdom from a wide array of philosophers, Christian, non-Christian, and even secular. The other half or so of the book is his own thoughts and messages to us.

It's structured as a "daily devotional", and each day's entry has a particular topic or theme--the main points of which are (in this edition, though apparently not in the original work of Tolstoy's) conveniently italicized for us. Tolstoy was imperfect and inconsistent just like every other genius. (What IS "consistency"? Even machines and robots and assembly-lines make mistakes...) But he was much to be admired, I feel, for his often radical stands for conscience and truth in a typically corrupt contemporary society--in his case, Russia's.

He made many controversial but impressive decisions (giving away much of his wealth, starting at least one Christian community, and voluntarily becoming a laborer, though he was by birth a privileged Count and aristocrat); he wrote many controversial works (like "The Kreutzer Sonata", a short story which was mostly a diatribe against lust and sexual politics, and which even encouraged celibacy in marriages!), and made many controversial statements (for instance, calling his two earlier, famous, epic novels "Anna Karenina" and "War & Peace", "the works of an idle mind," if memory serves.) He was a genuinely born-again Christian, but he was uncommonly friendly and open-minded toward other faiths and philosophers, as long as he discerned in them a genuine interest in truth and love. This book shows how "ecumenical" (in the best sense of that word) he came to be, in his old age. Yes, he might be divisive, but he was an honest seeker of truth, and I look forward to meeting him in Heaven. This "daily devotional"--a swan song, of sorts--is attractively typeset, formatted, and bound, and (most importantly) will surely give the seeker of truth many wise words & perspectives to meditate upon.

15 people found this helpful

HelpfulComment Report abuse

Frank Voehl

5.0 out of 5 stars Get This One on Your Calendar TodayReviewed in the United States on February 1, 2014

Verified Purchase

Leo Tolstoy once called this book his greatest work because there are contained within this book some thoughts from many of the greatest minds that Tolstoy admired. He believed that the only really true enduring religion is one which all people could share, and accordingly he was not one for preaching the dogma of any specific religion, by taking general ideas from the Bible, Koran, Talmud, Greek philosophy, and Buddhist teaching, along with thoughts from great thinkers such as Marcus Aurelius. When one reads this book, they are acutely aware that these deep thinkers and their religions share much more in common than in conflict.

Readers beware that Tolstoy is not directly quoting these people,; he is more or less paraphrasing them in his own words and style to make them more readable and pertinent. Each page is a days worth of quotes pertaining to a particular theme with one quote highlighted by Tolstoy. A weakness is that it has omitted his Weekly Messages, each one consisting on 5-10 pages, which make the whole document a more complete package as a whole (perhaps one day these too will be translated into English as a companion book).

What I like about this book most of all is using it as a day-by-day guide to illuminate one's own path of a life, which is worth living with a brightness undimmed by time. Another useful feature is that for each day one paragraph is in italics to condense the essence of the author's teachings for that day -- providing the essence of the day's thought.

A real treasure and a worthwhile read.

14 people found this helpful

---

Top international reviews

Translate all reviews to English

Patrick Sullivan

5.0 out of 5 stars Medicine For The SoulReviewed in Canada on January 7, 2020

Verified Purchase

This book is a brilliant collection of wisdom, from some of the world`s greatest thinkers. The list of people includes; many philosophers, writers, world leaders, and various religious leaders. Some secular-minded readers, may not appreciate the large content of religious citations. However, there is such a wide range of materials available. This will allow the reader to pick and choose, what they find most interesting.

Hats off to Tolstoy for a job well done! This book gets a very high recommendation.

One person found this helpful

HelpfulReport abuse

15 people found this helpful

HelpfulComment Report abuse

Frank Voehl

5.0 out of 5 stars Get This One on Your Calendar TodayReviewed in the United States on February 1, 2014

Verified Purchase

Leo Tolstoy once called this book his greatest work because there are contained within this book some thoughts from many of the greatest minds that Tolstoy admired. He believed that the only really true enduring religion is one which all people could share, and accordingly he was not one for preaching the dogma of any specific religion, by taking general ideas from the Bible, Koran, Talmud, Greek philosophy, and Buddhist teaching, along with thoughts from great thinkers such as Marcus Aurelius. When one reads this book, they are acutely aware that these deep thinkers and their religions share much more in common than in conflict.

Readers beware that Tolstoy is not directly quoting these people,; he is more or less paraphrasing them in his own words and style to make them more readable and pertinent. Each page is a days worth of quotes pertaining to a particular theme with one quote highlighted by Tolstoy. A weakness is that it has omitted his Weekly Messages, each one consisting on 5-10 pages, which make the whole document a more complete package as a whole (perhaps one day these too will be translated into English as a companion book).

What I like about this book most of all is using it as a day-by-day guide to illuminate one's own path of a life, which is worth living with a brightness undimmed by time. Another useful feature is that for each day one paragraph is in italics to condense the essence of the author's teachings for that day -- providing the essence of the day's thought.

A real treasure and a worthwhile read.

14 people found this helpful

---

Top international reviews

Translate all reviews to English

Patrick Sullivan

5.0 out of 5 stars Medicine For The SoulReviewed in Canada on January 7, 2020

Verified Purchase

This book is a brilliant collection of wisdom, from some of the world`s greatest thinkers. The list of people includes; many philosophers, writers, world leaders, and various religious leaders. Some secular-minded readers, may not appreciate the large content of religious citations. However, there is such a wide range of materials available. This will allow the reader to pick and choose, what they find most interesting.

Hats off to Tolstoy for a job well done! This book gets a very high recommendation.

One person found this helpful

HelpfulReport abuse

----

Amanda

Nov 29, 2010Amanda rated it it was amazing

A precious collection of quotes and snippets of text from The Talmud, The Bible, The Qur'an, The Bhagavad Gita, various poets, authors, and other religious, philosophical, and cultural texts. Hand-picked carefully by Tolstoy. One page for each day.

flag10 likes · Like · see review

Maggie

Jul 09, 2012Maggie rated it really liked it

My bed time great companion. It smoothes one's thought and is very inspiring in different school of thoughts, covering from the East to the West, ancient to now. It is too lucky of us to have this book as Tolstoy finished it as one of the biggest projects before his death. Tolstoy, why everytime I flip over a page of your words with hesitations, with the doubts in myself of being incapable of taking in your great thoughts and with fears of my book thay would run out sooner with one more page completed. Such an heartache, but worthy to be tolerated. :)

Big thanks to the storekeeper of a little bookstore on Toorak Road. I am just blessed to have exchanged those words and dreams with you. Wish you all well! (less)

flag6 likes · Like · comment · see review

David Gross

Feb 07, 2020David Gross rated it did not like it

Shelves: non-fiction

While there are a few pearls of wisdom scattered here and there in this collection, most of it is vague, shallow platitudenizing suitable for new age refrigerator-magnets. It stands as a warning that a mind of Tolstoy's caliber could have become so vulnerable to so much Sunday School poppycock.

Also: it's eye-rollingly repetitive.

And: the quotes are often Tolstoy's paraphrases rather than the actual words of the people he attributes them to... and sometimes they seem to be simplified in a way that does not respect the nuances of the original. (less)

flag6 likes · Like · comment · see review

Raymond

Jul 04, 2019Raymond rated it liked it

A good source of wisdom quotes from Tolstoy and others. Several quotes with a common theme are featured for each day of the year.

flag5 likes · Like · comment · see review

Tara

Feb 28, 2008Tara rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

This is a thought for every day that is encouraging and true

flag5 likes · Like · comment · see review

Manik Sukoco

Dec 24, 2015Manik Sukoco rated it really liked it · review of another edition

This extraordinary volume of selections from Leo Tolstoy's writings from his final years is a treasure, and it has a spirit of love and peace that one can even feel as one holds this book in one's hands. It is a delight and inspiration to read, whether one chooses to read it through from cover to cover, or use it as one would a daily devotional; to start each day with Tolstoy's wisdom, is to start the day with a quiet joy, and fresh understanding of what lies ahead. For each day, there is a chapter of approximately 125-150 words, and many include quotes from the world's great thinkers, from Confucius to Henry David Thoreau, and from Buddhist proverbs to the Talmud.

The themes range from one's spiritual life to the mundane, to the core of all things, love, and cover all relevant topics of the human condition. Though these thoughts were written from the years 1903 through 1910, they are as relevant today as ever. "Wise Thoughts for Every Day" is truly a "guide to living a good life" in any age.

The translation has a lucid beauty, and also a rare simplicity, making Tolstoy's thoughts understandable and highly readable. Those who stay away from Russian literature thinking it too complex should not overlook this superb book, which will appeal to anyone seeking truth and enlightenment, young and old alike.

The layout is wonderful, and it is a sturdily constructed book, with 365 pages of wisdom. This was Tolstoy's favorite of all his works, and he would have been so proud of this volume, in its first translation into English; it is a classic that belongs on every bookshelf, to be read and re-read as the years go by. (less)

flag6 likes · Like · comment · see review

Aidan Reid

Oct 01, 2018Aidan Reid rated it really liked it

Some gems in here:

"When you emerged into this world you cried, while everyone else was overjoyed. Try to see to it that, when you leave this world, everyone cries, while you alone smile."

"The more accustomed we get to doing with less, the less threatening we find deprivation."

"Wealth is like manure: it stinks when it is piled up, but when it is scattered about the Earth it fertilises it."

"Look upon your thoughts as if they were your guests, and your desires as if they were your children."

- Surprised by the number of quotes related to vegetarianism, anti-war and opposition to traditional orthodox religion. Recommended reading. (less)

flag3 likes · Like · comment · see review

Marina Fraser

Jun 01, 2011Marina Fraser rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

a great collection of wise thoughts

and quotations by

great writers

from all over the world

flag3 likes · Like · comment · see review

Christina

Feb 17, 2019Christina rated it did not like it · review of another edition

Shelves: dnf, personal-library

I gave this book a shot from January 1 til mid-February, but it's just not doing it for me. It's too religious. I prefer The Daily Stoic, which I find 10000x better and more suitable for my life.

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Octavia Cade

Mar 04, 2018Octavia Cade rated it it was ok · review of another edition

Shelves: religion, philosophy

It's always tempting, when reading the great novelists especially, to try to sift through the text to discover something of their own, personal opinions and beliefs. It can be tricky - we can misinterpret, or see things we want to see, or even ascribe meaning where there is none, particularly. With a book like this it's easier: Tolstoy made his own "quote of the day" calendar, essentially, except there's more than one (themed) quote per day and he adds a little piece of commentary of his own - sometimes as little as a sentence, sometimes as much as a couple of paragraphs. This was his pet project, according to the introduction, and readers can see what questions of ethics and philosophy and religion mattered to him most. The vast bulk of the subject matter is religious (particularly Christian, though a substantial amount comes from other traditions) and not being religious myself I can admire the writing and the emphasis on kindness, for example, without sympathising with everything that Tolstoy does. He seems to have a consistent hate-on for science, for example, and it's pretty clear he thinks it's a waste of time and brain space when people could be focusing on their spiritual life and so forth. At one point, there's a piece of writing that laments the waste of intellect in figuring our why water freezes or (my favourite!) how diseases spread, because goodness knows its easier to contemplate the divine in perfect happiness if all your children are dead of whooping cough. The book would get three stars from me if it weren't for that particular emphasis.

No higher, however. The introduction kind of poisoned the book for me and the disappointment lasted. Apparently in the original text (one of them at least) Tolstoy wrote what seemed to be very well-regarded short stories, one for each week of the year. But, the translator says, they didn't appear in all editions and they're quite long all together (!) so he didn't bother. Frankly, I'd rather have read the stories, and given that Tolstoy's great novels were massive doorstopper books then surely the page count could have been increased here to compensate.

(less)

flag2 likes · Like · 1 comment · see review

Rob

Mar 18, 2013Rob rated it liked it

This book is a sort of daily proverb calendar compiled and/or written by Leo Tolstoy. There are 365 pages of quotes, philosophical ramblings, or scriptural verses that are tied together by a topic. The topics include such things as wealth, poverty, education, intellect, science, faith, effort, prayer, civility, self-improvement, and so on. Tolstoy borrows from a variety of religious texts, particularly the Gospels and the Talmud. And there are certain authors and philosophers that he tends to quote often as well including Kant, Ruskin, Emmerson, and Thoreau. About half of the text appears to be his own original thoughts. It is all titled 'Calendar of Wisdom', and there certainly is a lot of wisdom found in the pages, although some proverbs appear to be poetic but not really meaningful. There is also a portion of the radical or ascetic Christian belief system that Tolstoy adopted later on in life, which I found interesting.

I really liked the idea of what Tolstoy did: compiling and organizing all of the the thoughts, ideas, quotes, and philosophies that have shaped your outlook on life, and adding a few of your own. The book was good food for thought, and while the truth of some quotes could be debated, it presented a challenge in any case that forced me to consider ideas I hadn't spent much time thinking about before. I left the book completely marked with the pearls of wisdom that appealed to me most. Here are a few short ones for a sampling:

"It is not the blaming of evil but the glorifying of goodness that creates harmony in our lives." (Lucy Mallory)

"For a Christian, the love of one's motherland can be an obstacle to the love of one's neighbor." (Tolstoy)

"The more people speak, the less desire they have to act." (Thomas Carlyle)

"A victory over oneself is a bigger and a better victory than a victory over thousands of people in a score of battles..." (Dhammapada)

(less)

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Robin

Jan 06, 2019Robin rated it did not like it

I am giving up on this pretty early in the year.

I read ahead a few days, and in the first 10 days, I found only about 3 daily thoughts of wisdom that I enjoyed. Most of them are taking from religious books which while in theory could be good/interesting are so far written in very old styles that don't really add anything.

The only good quotes sofar came from Thomas Jefferson and Confucius, and there must be much better books out there with a much higher ratio of good quotes to bad quotes.

So perhaps I will try this again next year, but for now I'm going to 1-star this.

There was also just way way way too much religion in there for my taste (less)

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Cheri

Jan 07, 2009Cheri rated it liked it

I did not realize how much religious content would be in the book. There was however a lot of other material I enjoyed reading. I particulary enjoyed reading about the various quotes on vegetarianism. A nice book to read through and go back to your favorite verses for inspiration.

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Mark Esping

Feb 03, 2014Mark Esping rated it it was amazing

To be read one day at a time. Starting my third time through. Amazing the people that Tolstoy read. I always read the days readings before breakfast and then my wife and I start the day with those topics.

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Amro Osman

Oct 05, 2014Amro Osman rated it it was amazing

I lost count how many times I've been inspired throughout this book. A truly eye opening read.

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Marina M.frazer

Jun 01, 2011Marina M.frazer rated it it was amazing

great

read

for every day

of the year -

i keep it on my desk

and read a page a day

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Nick

Jan 16, 2017Nick rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

Shelves: philosopy, authors-tolstoy

One of those books you can read again and again. Religion, ethics, philosophy- all good for reflection.

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Natalia

Dec 19, 2018Natalia rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

Such a joy to have around the house.

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Joy

Aug 09, 2014Joy rated it really liked it

I love quotes, so Tolstoy's selections on varied topics was most interesting. I'm reminded that you learn a lot about someone by the wisdom they appreciate. This collection was Tolstoy's last major work and a project of 15 years. Examples: "Those who are in the mountains can see the sun rise sooner than those in the valley." "A person who loves himself has few competitors." "He has power who can keep quiet in an argument even when he is right."

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Mark

Jul 25, 2011Mark rated it liked it

Shelves: spiritual, philosophy

I find it hard to sit and just read it "page by page-day by day" So I take it in chunks. I agree with a great deal of what I find, disagree with some,a s it ought to be for someone who draws their own conclusions on the world. However, his general philosophy is so sympatico with my on on too many things, to pass it off and say "well, I Don't Care if I finish it this year, or not"- I plan to get through the whole thing, then, pass it on to an interested friend...

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Lane Anderson

Jan 17, 2013Lane Anderson rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

I've been turning to this book every morning for a while now. Tolstoy was a great thinker, and his thoughts on religion and philosophy are a frequently-sought but rarely-found source of great wisdom. I highly recommend this book as a daily reader!

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Arlo

Jun 12, 2017Arlo rated it really liked it

Somewhat a book of affirmations. Tolstoy is Christian and expresses his views on Christianity. He uses all of the world's religions in a sense to get across his view on life.

As a vegan his views on meat eating were refreshing.

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Craig

May 18, 2012Craig rated it it was amazing

One of the 5 books I keep on my shelf at work to ground me, to re-set my moral compass, and to remind me of what is important. Many of the religious quotes do not resonate for me but the rest does in a big way.

flag1 like · Like · 2 comments · see review

Ivey Coss

Feb 27, 2013Ivey Coss rated it it was amazing · review of another edition

Shelves: constant-reference

These juicy little nuggets of timeless wisdom help to jar the mind out of all that entangles it from more theories, more teachings, more formulas and the barrage of of "NEW" that comes out every day!

It's simple and pointed with scriptures to back it up! A joy to read each day!

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

John

Jan 02, 2019John rated it it was ok

Rated: D+

This book was given to me by participants in a workshop that I delivered. It is a day-by-day listing of quotation that Tolstoy put together with each day having a common theme. Based on the wide variety of quotation from various religious sources, Tolstoy has an open theology to accept ideas for numerous belief systems. Consequently, I found most of the ideas more of a humanistic world view which often is antithetical to a biblical world view. With thousands of quotations, only a handful were memorable. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Vizi Andrei

Nov 27, 2019Vizi Andrei rated it liked it

Leo Tolstoy is easily one of my favorite thinkers. The concept of the book is clever; in an abundant world, knowledge is not about gathering information, but about filtering it.

There are many (way too many) books (and increasingly more) which are not to be read in full, but in small parts. This book is to be read in full.

Anyway, I found many reflections to be extremely repetitive (which could indeed be a virtue: repetition is the mother of all learning), but there was an excess of it to the point that you get bored. Also, the book is way too religious. I'm not against religion, but this book is meant to be about wisdom, not religion. Of course, wisdom could have religion in it; but, again, there's an excess. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

2019/09/29

Leo Tolstoy - Wikipedia

Leo Tolstoy - Wikipedia

References

External links

Leo Tolstoy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search"Tolstoy" and "Tolstoi" redirect here. For other uses, see Tolstoy (disambiguation).

"Lev Tolstoy" redirects here. For the rural locality and the railway station in Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, see Lev Tolstoy (rural locality).

This name uses Eastern Slavic naming customs; the patronymic is Nikolayevich and the family name is Tolstoy.

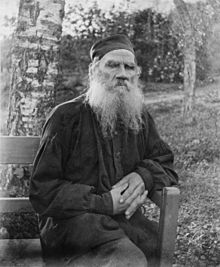

Leo Tolstoy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Leo Tolstoy in his later years. Early 20th century. | |||

| Native name | Лев Николаевич Толстой | ||

| Born | Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy 9 September 1828 Yasnaya Polyana, Tula Governorate, Russian Empire | ||

| Died | 20 November 1910 (aged 82) Astapovo, Ryazan Governorate, Russian Empire | ||

| Resting place | Yasnaya Polyana | ||

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, playwright, essayist | ||

| Language | Russian | ||

| Nationality | Russian | ||

| Period | 1847–1910 | ||

| Literary movement | Realism | ||

| Notable works | War and Peace Anna Karenina The Death of Ivan Ilyich The Kingdom of God Is Within You Resurrection | ||

| Spouse | Sophia Behrs (m. 1862) | ||

| Children | 14 | ||

| Signature | |||

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy[note 1] (/ˈtoʊlstɔɪ,  listen); 9 September [O.S. 28 August] 1828 – 20 November [O.S. 7 November] 1910), usually referred to in English as Leo Tolstoy, was a Russian writer who is regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time.[2] He received multiple nominations for Nobel Prize in Literature every year from 1902 to 1906, and nominations for Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, 1902 and 1910, and his miss of the prize is a major Nobel prize controversy.[3][4][5][6]

listen); 9 September [O.S. 28 August] 1828 – 20 November [O.S. 7 November] 1910), usually referred to in English as Leo Tolstoy, was a Russian writer who is regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time.[2] He received multiple nominations for Nobel Prize in Literature every year from 1902 to 1906, and nominations for Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, 1902 and 1910, and his miss of the prize is a major Nobel prize controversy.[3][4][5][6]

Born to an aristocratic Russian family in 1828,[2] he is best known for the novels War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877),[7] often cited as pinnacles of realist fiction.[2] He first achieved literary acclaim in his twenties with his semi-autobiographical trilogy, Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852–1856), and Sevastopol Sketches (1855), based upon his experiences in the Crimean War. Tolstoy's fiction includes dozens of short stories and several novellas such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), Family Happiness (1859), and Hadji Murad (1912). He also wrote plays and numerous philosophical essays.

In the 1870s Tolstoy experienced a profound moral crisis, followed by what he regarded as an equally profound spiritual awakening, as outlined in his non-fiction work A Confession (1882). His literal interpretation of the ethical teachings of Jesus, centering on the Sermon on the Mount, caused him to become a fervent Christian anarchist and pacifist.[2] Tolstoy's ideas on nonviolent resistance, expressed in such works as The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894), were to have a profound impact on such pivotal 20th-century figures as Mahatma Gandhi[8] and Martin Luther King Jr.[9] Tolstoy also became a dedicated advocate of Georgism, the economic philosophy of Henry George, which he incorporated into his writing, particularly Resurrection (1899).

Contents

Origins

Main article: Tolstoy family

The Tolstoys were a well-known family of old Russian nobility who traced their ancestry to a mythical nobleman named Indris described by Pyotr Tolstoy as arriving "from Nemec, from the lands of Caesar" to Chernigov in 1353 along with his two sons Litvinos (or Litvonis) and Zimonten (or Zigmont) and a druzhina of 3000 people.[10][11] While the word "Nemec" has been long used to describe Germans only, at that time it was applied to any foreigner who didn't speak Russian (from the word nemoy meaning mute).[12] Indris was then converted to Eastern Orthodoxy under the name of Leonty and his sons – as Konstantin and Feodor, respectively. Konstantin's grandson Andrei Kharitonovich was nicknamed Tolstiy (translated as fat) by Vasily II of Moscow after he moved from Chernigov to Moscow.[10][11]

Because of the pagan names and the fact that Chernigov at the time was ruled by Demetrius I Starshy some researches concluded that they were Lithuanians who arrived from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[10][13][14] At the same time, no mention of Indris was ever found in the 14th – 16th-century documents, while the Chernigov Chronicles used by Pyotr Tolstoy as a reference were lost.[10] The first documented members of the Tolstoy family also lived during the 17th century, thus Pyotr Tolstoy himself is generally considered the founder of the noble house, being granted the title of count by Peter the Great.[15][16]

Life and career

Tolstoy was born at Yasnaya Polyana, a family estate 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) southwest of Tula, Russia, and 200 kilometres (120 mi) south of Moscow. He was the fourth of five children of Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy (1794–1837), a veteran of the Patriotic War of 1812, and Countess Mariya Tolstaya (née Volkonskaya; 1790–1830). After his mother died when he was two and his father when he was nine,[17] Tolstoy and his siblings were brought up by relatives.[2] In 1844, he began studying law and oriental languages at Kazan University, where teachers described him as "both unable and unwilling to learn."[17] Tolstoy left the university in the middle of his studies,[17] returned to Yasnaya Polyana and then spent much of his time in Moscow, Tula and Saint Petersburg, leading a lax and leisurely lifestyle.[2] He began writing during this period,[17] including his first novel Childhood, a fictitious account of his own youth, which was published in 1852.[2] In 1851, after running up heavy gambling debts, he went with his older brother to the Caucasus and joined the army. Tolstoy served as a young artillery officer during the Crimean War and was in Sevastopol during the 11-month-long siege of Sevastopol in 1854–55,[18] including the Battle of the Chernaya. During the war he was recognised for his bravery and courage and promoted to lieutenant.[18] He was appalled by the number of deaths involved in warfare,[17] and left the army after the end of the Crimean War.[2]

His conversion from a dissolute and privileged society author to the non-violent and spiritual anarchist of his latter days was brought about by his experience in the army as well as two trips around Europe in 1857 and 1860–61. Others who followed the same path were Alexander Herzen, Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. During his 1857 visit, Tolstoy witnessed a public execution in Paris, a traumatic experience that would mark the rest of his life. Writing in a letter to his friend Vasily Botkin: "The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens ... Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere."[19] Tolstoy's concept of non-violence or Ahimsa was bolstered when he read a German version of the Tirukkural.[20] He later instilled the concept in Mahatma Gandhi through his A Letter to a Hindu when young Gandhi corresponded with him seeking his advice.[21][22]

His European trip in 1860–61 shaped both his political and literary development when he met Victor Hugo, whose literary talents Tolstoy praised after reading Hugo's newly finished Les Misérables. The similar evocation of battle scenes in Hugo's novel and Tolstoy's War and Peace indicates this influence. Tolstoy's political philosophy was also influenced by a March 1861 visit to French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, then living in exile under an assumed name in Brussels. Apart from reviewing Proudhon's forthcoming publication, La Guerre et la Paix (War and Peace in French), whose title Tolstoy would borrow for his masterpiece, the two men discussed education, as Tolstoy wrote in his educational notebooks: "If I recount this conversation with Proudhon, it is to show that, in my personal experience, he was the only man who understood the significance of education and of the printing press in our time."

Fired by enthusiasm, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana and founded thirteen schools for the children of Russia's peasants, who had just been emancipated from serfdom in 1861. Tolstoy described the school's principles in his 1862 essay "The School at Yasnaya Polyana".[23] Tolstoy's educational experiments were short-lived, partly due to harassment by the Tsarist secret police. However, as a direct forerunner to A.S. Neill's Summerhill School, the school at Yasnaya Polyana[24] can justifiably be claimed the first example of a coherent theory of democratic education.

Personal life

The death of his brother Nikolay in 1860 had an impact on Tolstoy, and led him to a desire to marry.[17] On 23 September 1862, Tolstoy married Sophia Andreevna Behrs, who was sixteen years his junior and the daughter of a court physician. She was called Sonya, the Russian diminutive of Sofia, by her family and friends.[25] They had 13 children, eight of whom survived childhood:[26]

- Count Sergei Lvovich Tolstoy (1863–1947), composer and ethnomusicologist

- Countess Tatyana Lvovna Tolstaya (1864–1950), wife of Mikhail Sergeevich Sukhotin

- Count Ilya Lvovich Tolstoy (1866–1933), writer

- Count Lev Lvovich Tolstoy (1869–1945), writer and sculptor

- Countess Maria Lvovna Tolstaya (1871–1906), wife of Nikolai Leonidovich Obolensky

- Count Peter Lvovich Tolstoy (1872–1873), died in infancy

- Count Nikolai Lvovich Tolstoy (1874–1875), died in infancy

- Countess Varvara Lvovna Tolstaya (1875–1875), died in infancy

- Count Andrei Lvovich Tolstoy (1877–1916), served in the Russo-Japanese War

- Count Michael Lvovich Tolstoy (1879–1944)

- Count Alexei Lvovich Tolstoy (1881–1886)

- Countess Alexandra Lvovna Tolstaya (1884–1979)

- Count Ivan Lvovich Tolstoy (1888–1895)

The marriage was marked from the outset by sexual passion and emotional insensitivity when Tolstoy, on the eve of their marriage, gave her his diaries detailing his extensive sexual past and the fact that one of the serfs on his estate had borne him a son.[25] Even so, their early married life was happy and allowed Tolstoy much freedom and the support system to compose War and Peace and Anna Karenina with Sonya acting as his secretary, editor, and financial manager. Sonya was copying and hand-writing his epic works time after time. Tolstoy would continue editing War and Peace and had to have clean final drafts to be delivered to the publisher.[25][27]

However, their later life together has been described by A.N. Wilson as one of the unhappiest in literary history. Tolstoy's relationship with his wife deteriorated as his beliefs became increasingly radical. This saw him seeking to reject his inherited and earned wealth, including the renunciation of the copyrights on his earlier works.

Some of the members of the Tolstoy family left Russia in the aftermath of the 1905 Russian Revolution and the subsequent establishment of the Soviet Union, and many of Leo Tolstoy's relatives and descendants today live in Sweden, Germany, the United Kingdom, France and the United States. Among them are Swedish jazz singer Viktoria Tolstoy and the Swedish landowner Christopher Paus, whose family owns the major estate Herresta outside Stockholm.[28]

One of his great-great-grandsons, Vladimir Tolstoy (born 1962), is a director of the Yasnaya Polyana museum since 1994 and an adviser to the President of Russia on cultural affairs since 2012.[29][30] Ilya Tolstoy's great-grandson, Pyotr Tolstoy, is a well-known Russian journalist and TV presenter as well as a State Duma deputy since 2016. His cousin Fyokla Tolstaya (born Anna Tolstaya in 1971), daughter of the acclaimed Soviet Slavist Nikita Tolstoy (ru) (1923–1996), is also a Russian journalist, TV and radio host.[31]

Novels and fictional works

Tolstoy is considered one of the giants of Russian literature; his works include the novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina and novellas such as Hadji Murad and The Death of Ivan Ilyich.

Tolstoy's earliest works, the autobiographical novels Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852–1856), tell of a rich landowner's son and his slow realization of the chasm between himself and his peasants. Though he later rejected them as sentimental, a great deal of Tolstoy's own life is revealed. They retain their relevance as accounts of the universal story of growing up.

Tolstoy served as a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment during the Crimean War, recounted in his Sevastopol Sketches. His experiences in battle helped stir his subsequent pacifism and gave him material for realistic depiction of the horrors of war in his later work.[32]

His fiction consistently attempts to convey realistically the Russian society in which he lived.[33] The Cossacks (1863) describes the Cossack life and people through a story of a Russian aristocrat in love with a Cossack girl. Anna Karenina (1877) tells parallel stories of an adulterous woman trapped by the conventions and falsities of society and of a philosophical landowner (much like Tolstoy), who works alongside the peasants in the fields and seeks to reform their lives. Tolstoy not only drew from his own life experiences but also created characters in his own image, such as Pierre Bezukhov and Prince Andrei in War and Peace, Levin in Anna Karenina and to some extent, Prince Nekhlyudov in Resurrection.

War and Peace is generally thought to be one of the greatest novels ever written, remarkable for its dramatic breadth and unity. Its vast canvas includes 580 characters, many historical with others fictional. The story moves from family life to the headquarters of Napoleon, from the court of Alexander I of Russia to the battlefields of Austerlitz and Borodino. Tolstoy's original idea for the novel was to investigate the causes of the Decembrist revolt, to which it refers only in the last chapters, from which can be deduced that Andrei Bolkonsky's son will become one of the Decembrists. The novel explores Tolstoy's theory of history, and in particular the insignificance of individuals such as Napoleon and Alexander. Somewhat surprisingly, Tolstoy did not consider War and Peace to be a novel (nor did he consider many of the great Russian fictions written at that time to be novels). This view becomes less surprising if one considers that Tolstoy was a novelist of the realist school who considered the novel to be a framework for the examination of social and political issues in nineteenth-century life.[34] War and Peace (which is to Tolstoy really an epic in prose) therefore did not qualify. Tolstoy thought that Anna Karenina was his first true novel.[35]

After Anna Karenina, Tolstoy concentrated on Christian themes, and his later novels such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) and What Is to Be Done? develop a radical anarcho-pacifist Christian philosophy which led to his excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901.[36] For all the praise showered on Anna Karenina and War and Peace, Tolstoy rejected the two works later in his life as something not as true of reality.[37]

In his novel Resurrection, Tolstoy attempts to expose the injustice of man-made laws and the hypocrisy of institutionalized church. Tolstoy also explores and explains the economic philosophy of Georgism, of which he had become a very strong advocate towards the end of his life.

Tolstoy also tried himself in poetry with several soldier songs written during his military service and fairy tales in verse such as Volga-bogatyr and Oaf stylized as national folk songs. They were written between 1871 and 1874 for his Russian Book for Reading, a collection of short stories in four volumes (total of 629 stories in various genres) published along with the New Azbuka textbook and addressed to schoolchildren. Nevertheless, he was skeptical about poetry as a genre. As he famously said, "Writing poetry is like ploughing and dancing at the same time". According to Valentin Bulgakov, he criticised poets, including Alexander Pushkin, for their "false" epithets used "simply to make it rhyme".[38][39]

Critical appraisal by other authors

Tolstoy's contemporaries paid him lofty tributes. Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who died thirty years before Tolstoy's death, thought him the greatest of all living novelists. Gustave Flaubert, on reading a translation of War and Peace, exclaimed, "What an artist and what a psychologist!" Anton Chekhov, who often visited Tolstoy at his country estate, wrote, "When literature possesses a Tolstoy, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even when you know you have achieved nothing yourself and are still achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be, because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature." The 19th-century British poet and critic Matthew Arnold opined that "A novel by Tolstoy is not a work of art but a piece of life."[2]

Later novelists continued to appreciate Tolstoy's art, but sometimes also expressed criticism. Arthur Conan Doyle wrote "I am attracted by his earnestness and by his power of detail, but I am repelled by his looseness of construction and by his unreasonable and impracticable mysticism."[40] Virginia Woolf declared him "the greatest of all novelists."[2] James Joyce noted that "He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical!" Thomas Mann wrote of Tolstoy's seemingly guileless artistry: "Seldom did art work so much like nature." Vladimir Nabokov heaped superlatives upon The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Anna Karenina; he questioned, however, the reputation of War and Peace, and sharply criticized Resurrection and The Kreutzer Sonata.

Religious and political beliefs

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Tolstoy dressed in peasant clothing, by Ilya Repin (1901)

After reading Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation, Tolstoy gradually became converted to the ascetic morality upheld in that work as the proper spiritual path for the upper classes: "Do you know what this summer has meant for me? Constant raptures over Schopenhauer and a whole series of spiritual delights which I've never experienced before. ... no student has ever studied so much on his course, and learned so much, as I have this summer"[41]

In Chapter VI of A Confession, Tolstoy quoted the final paragraph of Schopenhauer's work. It explained how the nothingness that results from complete denial of self is only a relative nothingness, and is not to be feared. The novelist was struck by the description of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu ascetic renunciation as being the path to holiness. After reading passages such as the following, which abound in Schopenhauer's ethical chapters, the Russian nobleman chose poverty and formal denial of the will:

But this very necessity of involuntary suffering (by poor people) for eternal salvation is also expressed by that utterance of the Savior (Matthew 19:24): "It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God." Therefore, those who were greatly in earnest about their eternal salvation, chose voluntary poverty when fate had denied this to them and they had been born in wealth. Thus Buddha Sakyamuni was born a prince, but voluntarily took to the mendicant's staff; and Francis of Assisi, the founder of the mendicant orders who, as a youngster at a ball, where the daughters of all the notabilities were sitting together, was asked: "Now Francis, will you not soon make your choice from these beauties?" and who replied: "I have made a far more beautiful choice!" "Whom?" "La povertà (poverty)": whereupon he abandoned every thing shortly afterwards and wandered through the land as a mendicant.[42]

In 1884, Tolstoy wrote a book called What I Believe, in which he openly confessed his Christian beliefs. He affirmed his belief in Jesus Christ's teachings and was particularly influenced by the Sermon on the Mount, and the injunction to turn the other cheek, which he understood as a "commandment of non-resistance to evil by force" and a doctrine of pacifism and nonviolence. In his work The Kingdom of God Is Within You, he explains that he considered mistaken the Church's doctrine because they had made a "perversion" of Christ's teachings. Tolstoy also received letters from American Quakers who introduced him to the non-violence writings of Quaker Christians such as George Fox, William Penn and Jonathan Dymond. Tolstoy believed being a Christian required him to be a pacifist; the consequences of being a pacifist, and the apparently inevitable waging of war by government, are the reason why he is considered a philosophical anarchist.

Later, various versions of "Tolstoy's Bible" would be published, indicating the passages Tolstoy most relied on, specifically, the reported words of Jesus himself.[43]

Mohandas K. Gandhi and other residents of Tolstoy Farm, South Africa, 1910

Tolstoy believed that a true Christian could find lasting happiness by striving for inner self-perfection through following the Great Commandment of loving one's neighbor and God rather than looking outward to the Church or state for guidance. His belief in nonresistance when faced by conflict is another distinct attribute of his philosophy based on Christ's teachings. By directly influencing Mahatma Gandhi with this idea through his work The Kingdom of God Is Within You (full text of English translation available on Wikisource), Tolstoy's profound influence on the nonviolent resistance movement reverberates to this day. He believed that the aristocracy were a burden on the poor, and that the only solution to how we live together is through anarchism.[citation needed]

He also opposed private property in land ownership[44] and the institution of marriage and valued the ideals of chastity and sexual abstinence (discussed in Father Sergius and his preface to The Kreutzer Sonata), ideals also held by the young Gandhi. Tolstoy's later work derives a passion and verve from the depth of his austere moral views.[45] The sequence of the temptation of Sergius in Father Sergius, for example, is among his later triumphs. Gorky relates how Tolstoy once read this passage before himself and Chekhov and that Tolstoy was moved to tears by the end of the reading. Other later passages of rare power include the personal crises that were faced by the protagonists of The Death of Ivan Ilyich, and of Master and Man, where the main character in the former or the reader in the latter are made aware of the foolishness of the protagonists' lives.

Tolstoy had a profound influence on the development of Christian anarchist thought.[46] The Tolstoyans were a small Christian anarchist group formed by Tolstoy's companion, Vladimir Chertkov (1854–1936), to spread Tolstoy's religious teachings. Philosopher Peter Kropotkin wrote of Tolstoy in the article on anarchism in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica:

Without naming himself an anarchist, Leo Tolstoy, like his predecessors in the popular religious movements of the 15th and 16th centuries, Chojecki, Denk and many others, took the anarchist position as regards the state and property rights, deducing his conclusions from the general spirit of the teachings of Jesus and from the necessary dictates of reason. With all the might of his talent, Tolstoy made (especially in The Kingdom of God Is Within You) a powerful criticism of the church, the state and law altogether, and especially of the present property laws. He describes the state as the domination of the wicked ones, supported by brutal force. Robbers, he says, are far less dangerous than a well-organized government. He makes a searching criticism of the prejudices which are current now concerning the benefits conferred upon men by the church, the state, and the existing distribution of property, and from the teachings of Jesus he deduces the rule of non-resistance and the absolute condemnation of all wars. His religious arguments are, however, so well combined with arguments borrowed from a dispassionate observation of the present evils, that the anarchist portions of his works appeal to the religious and the non-religious reader alike.[47]

Tolstoy organising famine relief in Samara, 1891

During the Boxer Rebellion in China, Tolstoy praised the Boxers. He was harshly critical of the atrocities committed by the Russians, Germans, Americans, Japanese, and other western troops. He accused them of engaging in slaughter when he heard about the lootings, rapes, and murders, in what he saw as Christian brutality. Tolstoy also named the two monarchs most responsible for the atrocities; Nicholas II of Russia and Wilhelm II of Germany.[48][49] Tolstoy, a famous sinophile, also read the works of Chinese thinker and philosopher, Confucius.[50][51][52] Tolstoy corresponded with the Chinese intellectual Gu Hongming and recommended that China remain an agrarian nation and warned against reform like what Japan implemented.

The Eight-Nation Alliance intervention in the Boxer Rebellion was denounced by Tolstoy as were the Philippine–American War and the Second Boer War between the British Empire and the two independent Boer republics.[53] The words "terrible for its injustice and cruelty" were used to describe the Czarist intervention in China by Tolstoy.[54] Confucius's works were studied by Tolstoy. The attack on China in the Boxer Rebellion was railed against by Tolstoy.[55] The war against China was criticized by Leonid Andreev and Gorkey. To the Chinese people, an epistle, was written by Tolstoy as part of the criticism of the war by intellectuals in Russia.[56] The activities of Russia in China by Nicholas II were described in an open letter where they were slammed and denounced by Leo Tolstoy in 1902.[57] Tolstoy corresponded with Gu Hongming and they both opposed the Hundred Day's Reform by Kang Youwei and agreed that the reform movement was perilous.[58] Tolstoys' ideology on non violence shaped the anarchist thought of the Society for the Study of Socialism in China.[59] Lao Zi and Confucius's teachings were studied by Tolstoy. Chinese Wisdom was a text written by Tolstoy. The Boxer Rebellion stirred Tolstoy's interest in Chinese philosophy.[60] The Boxer and Boxer wars were denounced by Tolstoy.[61]

Film footage of Tolstoy's 80th birthday at Yasnaya Polyana. Footage shows his wife Sofya (picking flowers in the garden), daughter Aleksandra (sitting in the carriage in the white blouse), his aide and confidante, V. Chertkov (bald man with the beard and mustache) and students. Filmed by Aleksandr Osipovich Drankov, 1908.

In hundreds of essays over the last 20 years of his life, Tolstoy reiterated the anarchist critique of the state and recommended books by Kropotkin and Proudhon to his readers, whilst rejecting anarchism's espousal of violent revolutionary means. In the 1900 essay, "On Anarchy", he wrote; "The Anarchists are right in everything; in the negation of the existing order, and in the assertion that, without Authority, there could not be worse violence than that of Authority under existing conditions. They are mistaken only in thinking that Anarchy can be instituted by a revolution. But it will be instituted only by there being more and more people who do not require the protection of governmental power ... There can be only one permanent revolution—a moral one: the regeneration of the inner man." Despite his misgivings about anarchist violence, Tolstoy took risks to circulate the prohibited publications of anarchist thinkers in Russia, and corrected the proofs of Kropotkin's "Words of a Rebel", illegally published in St Petersburg in 1906.[62]

Tolstoy was enthused by the economic thinking of Henry George, incorporating it approvingly into later works such as Resurrection (1899), the book that played a major factor in his excommunication.[63]

In 1908, Tolstoy wrote A Letter to a Hindu[64] outlining his belief in non-violence as a means for India to gain independence from British colonial rule. In 1909, a copy of the letter was read by Gandhi, who was working as a lawyer in South Africa at the time and just becoming an activist. Tolstoy's letter was significant for Gandhi, who wrote Tolstoy seeking proof that he was the real author, leading to further correspondence between them.[20]

Reading Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You also convinced Gandhi to avoid violence and espouse nonviolent resistance, a debt Gandhi acknowledged in his autobiography, calling Tolstoy "the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced". The correspondence between Tolstoy and Gandhi would only last a year, from October 1909 until Tolstoy's death in November 1910, but led Gandhi to give the name Tolstoy Colony to his second ashram in South Africa.[65] Besides nonviolent resistance, the two men shared a common belief in the merits of vegetarianism, the subject of several of Tolstoy's essays.[66]

Tolstoy also became a major supporter of the Esperanto movement. Tolstoy was impressed by the pacifist beliefs of the Doukhobors and brought their persecution to the attention of the international community, after they burned their weapons in peaceful protest in 1895. He aided the Doukhobors in migrating to Canada.[67] In 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, Tolstoy condemned the war and wrote to the Japanese Buddhist priest Soyen Shaku in a failed attempt to make a joint pacifist statement.

Towards the end of his life, Tolstoy become more and more occupied with the economic theory and social philosophy of Georgism.[68][69][70][71] He spoke of great admiration of Henry George, stating once that "People do not argue with the teaching of George; they simply do not know it. And it is impossible to do otherwise with his teaching, for he who becomes acquainted with it cannot but agree."[72] He also wrote a preface to George's Social Problems.[73] Tolstoy and George both rejected private property in land (the most important source of income of the passive Russian aristocracy that Tolstoy so heavily criticized) whilst simultaneously both rejecting a centrally planned socialist economy. Some assume that this development in Tolstoy's thinking was a move away from his anarchist views, since Georgism requires a central administration to collect land rent and spend it on infrastructure. However, anarchist versions of Georgism have also been proposed since.[74] Tolstoy's 1899 novel Resurrection explores his thoughts on Georgism in more detail and hints that Tolstoy indeed had such a view. It suggests the possibility of small communities with some form of local governance to manage the collective land rents for common goods; whilst still heavily criticising institutions of the state such as the justice system.

Death

Tolstoy's grave with flowers at Yasnaya Polyana

Tolstoy died in 1910, at the age of 82. Just prior to his death, his health had been a concern of his family, who were actively engaged in his care on a daily basis. During his last few days, he had spoken and written about dying. Renouncing his aristocratic lifestyle, he had finally gathered the nerve to separate from his wife, and left home in the middle of winter, in the dead of night.[75] His secretive departure was an apparent attempt to escape unannounced from Sophia's jealous tirades. She was outspokenly opposed to many of his teachings, and in recent years had grown envious of the attention which it seemed to her Tolstoy lavished upon his Tolstoyan "disciples".

Tolstoy died of pneumonia[76] at Astapovo railway station, after a day's journey by train south.[77] The station master took Tolstoy to his apartment, and his personal doctors were called to the scene. He was given injections of morphine and camphor.

The police tried to limit access to his funeral procession, but thousands of peasants lined the streets. Still, some were heard to say that, other than knowing that "some nobleman had died", they knew little else about Tolstoy.[78]

According to some sources, Tolstoy spent the last hours of his life preaching love, non-violence, and Georgism to his fellow passengers on the train.[79]

In films

A 2009 film about Tolstoy's final year, The Last Station, based on the novel by Jay Parini, was made by director Michael Hoffman with Christopher Plummer as Tolstoy and Helen Mirren as Sofya Tolstoya. Both performers were nominated for Oscars for their roles. There have been other films about the writer, including Departure of a Grand Old Man, made in 1912 just two years after his death, How Fine, How Fresh the Roses Were (1913), and Leo Tolstoy, directed by and starring Sergei Gerasimov in 1984.

There is also a famous lost film of Tolstoy made a decade before he died. In 1901, the American travel lecturer Burton Holmes visited Yasnaya Polyana with Albert J. Beveridge, the U.S. senator and historian. As the three men conversed, Holmes filmed Tolstoy with his 60-mm movie camera. Afterwards, Beveridge's advisers succeeded in having the film destroyed, fearing that documentary evidence of a meeting with the Russian author might hurt Beveridge's chances of running for the U.S. presidency.[80]

Bibliography

Main article: Leo Tolstoy bibliography

See also

- Anarchism and religion

- Christian vegetarianism

- Leo Tolstoy and Theosophy

- List of peace activists

- Tolstoyan movement

- Henry David Thoreau

- War & Peace (2016 TV series)

Notes

References

- ^ "Tolstoy". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j "Leo Tolstoy". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ "Nomination Database". old.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "Proclamation sent to Leo Tolstoy after the 1901 year's presentation of Nobel Prizes". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Hedin, Naboth (1 October 1950). "Winning the Nobel Prize". The Atlantic. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "Nobel Prize Snubs In Literature: 9 Famous Writers Who Should Have Won (Photos)". Huffington Post. 7 October 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Beard, Mary (5 November 2013). "Facing death with Tolstoy". The New Yorker.

- ^ Martin E. Hellman, Resist Not Evil in World Without Violence (Arun Gandhi ed.), M.K. Gandhi Institute, 1994, retrieved on 14 December 2006

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther; Clayborne Carson; et al. (2005). The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume V: Threshold of a New Decade, January 1959 – December 1960. University of California Press. pp. 149, 269, 248. ISBN 978-0-520-24239-5.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Vitold Rummel, Vladimir Golubtsov (1886). Genealogical Collection of Russian Noble Families in 2 Volumes. Volume 2 // The Tolstoys, Counts and Noblemen. Saint Petersburg: A.S. Suvorin Publishing House, p. 487

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ivan Bunin, The Liberation of Tolstoy: A Tale of Two Writers, p. 100

- ^ Nemoy/Немой word meaning from the Dahl's Explanatory Dictionary (in Russian)

- ^ Troyat, Henri (2001). Tolstoy. ISBN 978-0-8021-3768-5.

- ^ Robinson, Harlow (6 November 1983). "Six Centuries of Tolstoys". The New York Times.

- ^ Tolstoy coat of arms by All-Russian Armorials of Noble Houses of the Russian Empire. Part 2, 30 June 1798 (in Russian)

- ^ The Tolstoys article from Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, 1890–1907 (in Russian)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f "Author Data Sheet, Macmillan Readers" (PDF). Macmillan Publishers Limited. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Ten Things You Didn't Know About Tolstoy". BBC.

- ^ A.N. Wilson, Tolstoy (1988), p. 146

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rajaram, M. (2009). Thirukkural: Pearls of Inspiration. New Delhi: Rupa Publications. pp. xviii–xxi.

- ^ Tolstoy, Leo (14 December 1908). "A Letter to A Hindu: The Subjection of India-Its Cause and Cure". The Literature Network. Retrieved 12 February 2012. The Hindu Kural

- ^ Parel, Anthony J. (2002), "Gandhi and Tolstoy", in M.P. Mathai; M.S. John; Siby K. Joseph (eds.), Meditations on Gandhi: a Ravindra Varma festschrift, New Delhi: Concept, pp. 96–112, retrieved 8 September 2012

- ^ Tolstoy, Lev N.; Leo Wiener; translator and editor (1904). The School at Yasnaya Polyana – The Complete Works of Count Tolstoy: Pedagogical Articles. Linen-Measurer, Volume IV. Dana Estes & Company. p. 227.

- ^ Wilson, A.N. (2001). Tolstoy. W.W. Norton. p. xxi. ISBN 978-0-393-32122-7.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Susan Jacoby, "The Wife of the Genius" (19 April 1981) The New York Times

- ^ Feuer, Kathryn B. Tolstoy and the Genesis of War and Peace, Cornell University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8014-1902-6

- ^ War and Peace and Sonya. uchicago.edu.

- ^ Nikolai Puzin, The Lev Tolstoy House-Museum In Yasnaya Polyana (with a list of Leo Tolstoy's descendants), 1998

- ^ Vladimir Ilyich Tolstoy at the official Yasnaya Polyana website

- ^ "Persons ∙ Directory ∙ President of Russia". President of Russia.

- ^ "Толстые / Телеканал "Россия – Культура"". tvkultura.ru.

- ^ Government is Violence: essays on anarchism and pacifism. Leo Tolstoy – 1990 – Phoenix Press